Abstract

Background/Aims

The financial burden of caring for iron-related complications (IRCs) is an emerging medical problem in Korea, as in Western countries. We produced a preliminary estimate of the costs of treating patients for IRCs.

Methods

The medical records of patients who had received multiple transfusions were reviewed. Newly developed cardiomyopathy, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and liver cancer were defined as IRCs. The costs of laboratory studies, medication, oxygenation, intervention, and education were calculated using working criteria we defined. Costs that had a definite causal relationship with IRCs were included to produce as accurate an estimate as possible.

Results

Between 2002 and 2006, 650 patients with hematologic diseases, including 358 with acute leukemia, 102 with lymphoma, 58 with myelodysplastic syndrome or myeloproliferative disease, 46 with multiple myeloma, and 31 with chronic leukemia, received more than 10 units of red blood cells. Nine patients developed IRCs. The primary diagnoses of eight patients were aplastic anemia and that of one patient was chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Two patients who had diabetes were excluded because one was treated at another hospital and the other was diagnosed as oxymetholone-induced diabetes. Of the seven patients included, liver cirrhosis developed in two, heart failure in four, and diabetes mellitus in three. Some of them had two diagnoses. The total cost attributed to IRCs for the seven patients was 47,388,241 KRW (approximately 50,000 USD).

Conclusions

The medical costs of IRCs are considerable, and more effective iron-chelating therapy is necessary to save medical resources and improve patient care. More in the way of comprehensive health and economic studies of IRCs are needed to allow both clinicians and health-policy makers to make better decisions.

Keywords: Iron overload, Costs and cost analysis

INTRODUCTION

Secondary iron-overload causes various complications, such as liver cirrhosis, diabetes, and heart failure [1]. In Western countries, much experience has been accumulated with regard to chronic refractory anemia and its complications because of the high prevalence of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia. The survival of patients with thalassemia major has improved markedly, but the prevalence of severe complications such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and diabetes is still high.

In Korea, iron-related complications (IRCs) have not been a matter of concern. Patients with aplastic anemia or myelodysplastic syndrome can now live for a long time with supportive and curative treatments, including judicious blood transfusion and stem cell transplantation. Therefore, comprehensive studies of their secondary iron overload and its complications are needed. Consequently, we analyzed the medical costs of patients treated for IRCs at our institution.

METHODS

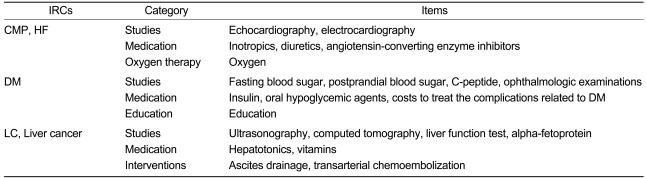

We searched the database of Seoul National University Blood Bank for patients transfused with more than ten units from 2002 to 2006. Their electronic medical records were reviewed to find patients with IRCs. The cost data for IRCs could be retrieved from electronic medical records for patients from 2002, when this records system was adopted at the hospital. The medical costs in the emergency room were included as either inpatient or outpatient costs. We defined items to assess the medical costs of IRCs, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

The tools used to the calculate medical costs for IRC*

IRCs, iron-related complications; CMP, cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; LC, liver cirrhosis.

*Charges for intravenous fluids and catheters were excluded.

Specific tools were developed for calculating the costs of IRCs.

If the main cause of admission was IRCs, all medical costs were included (e.g., the costs for inotropics and diuretics used to treat dyspnea due to heart failure). If the main cause of admission was not IRCs, medical costs that had a definite causal relationship were included. For example, if a patient with cholecystitis was treated for heart failure during the admission, only the costs of the care for heart failure were included. Outpatient costs were calculated in the same way as inpatient costs. Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis and liver cancer were defined as IRCs. Charges for diagnostic studies, medication and intervention were included. In the cases with cardiomyopathy and heart failure, charges for studies such as echocardiography and electrocardiography were included. Charges for inotropics (epinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine, digoxin, etc.), diuretics (furosemide, spironolactone, etc.), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ramipril, enalapril, etc.) and inhaled oxygen were included as charges for medication and intervention. Charges for intravenous fluids and catheters were excluded. In the cases with diabetes mellitus, charges for fasting blood sugar, post prandial blood sugar, C-peptide and ophthalmologic examinations were included as charges for diagnostic studies. Costs for insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, education, costs of treating any complications related to diabetes were included. In the cases with liver cirrhosis and liver cancer, charges for ultrasonography, computed tomography, liver function tests, alphafetoprotein, hepatotonics, vitamins, ascites drainage and transarterial chemoembolization were included.

Costs with vague causal relationships to IRCs were excluded. Complications that have complex etiologies were also excluded. IRCs included cardiomyopathy, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and liver cancer because they have definite causal relationships with iron overload. Infection is a known complication of iron overload, but infection-related costs were excluded because infection can also be a consequence of an immuno-compromised state due to underlying diseases. Strict criteria were applied for additional costs associated with IRCs. Costs for routine follow-up, treatment of underlying disease or iron overload itself were excluded (e.g., routine laboratory tests, serum ferritin, and deferoxamine administration). Costs in other departments for treating IRCs were excluded from the analysis (e.g., stroke with diabetes).

RESULTS

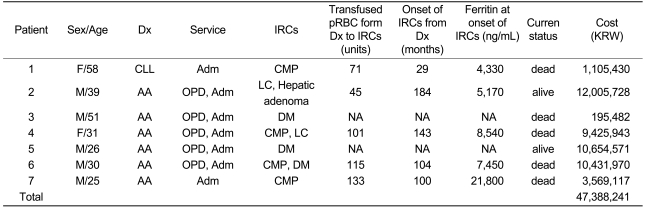

Between 2002 and 2006, 650 patients with various hematologic diseases, including 358 with acute leukemia, 102 with lymphoma, 58 with myelodysplastic syndrome or myeloproliferative disease, 31 with chronic leukemia, and 46 with multiple myeloma, were transfused more than 10 units of red blood cells. Nine patients who developed IRCs were studied for the cost analysis. The primary diagnoses of eight patients were aplastic anemia and that of one patient was chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Two patients with aplastic anemia who had diabetes were excluded because one patient was treated at another hospital and the other was diagnosed with oxymetholone-induced diabetes. Table 2 shows the basic characteristics of the patients included and their medical costs related to IRCs. Liver cirrhosis developed in two, heart failure in four, and diabetes in three patients. The total cost for the seven patients was 47,388,241 KRW (approximately 50,000 USD).

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of the patients and the medical cost associated with IRC*

*Dx, diagnosis; IRCs, iron-related complications; Tf, transfusion; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Adm, admission; OPD, outpatient department; DM, diabetes mellitus; CMP, cardiomyopathy; LC, liver cirrhosis; AA, aplastic anemia; NA, not available; pRBC, packed red blood cells.

DISCUSSION

One large retrospective study in Italy showed that transfusion dependency and secondary iron overload have a significant impact on survival in myelodysplastic syndromes [2]. In an era of rising medical costs, cost-benefit problems are at the center of public attention in medical decision-making. The quality and quantity of life achieved by medical interventions are difficult to measure in purely financial terms. Many patients suffer because of the medical expenses they incur, in addition to the diseases that afflict them. In particular, recent advances in hematology and medical oncology have forced patients and physicians to balance the benefits and expenses of medical treatment. In Western countries, cost analyses of IRCs and iron-chelating agents are actively being conducted. In one analysis involving 31 thalassemia patients in America, IRCs were a major cost determinant and medical expenses increased sharply with the number of complications [3]. A lack of compliance with chelating therapy was associated with IRCs and high mortality [4,5]. Efforts to improve compliance with iron-chelating therapy might decrease the rate of IRCs and consequently lower the medical expenses.

Medical care costs for IRCs are now a matter of concern in Korea, since patients with refractory anemia from various causes live longer with the advances that have been made in therapeutic measures. Effective iron-chelating therapy with deferoxamine is difficult because of its inconvenience and poor compliance. Recently, oral iron-chelators (deferasirox and deferiprone), which are thought to be more accessible to patients who do not tolerate the parenteral route, were developed as an alternative [6,7]. Nevertheless, the use of oral iron chelators increases medical costs. If the seven patients in this study had received deferasirox from the date of the primary diagnosis until the end of follow-up, the total cost for the iron-chelating therapy would be 3,027,299,612 KRW. One recent study compared the cost-effectiveness of two iron chelators: deferasirox and deferoxamine. They used a Markov model to estimate quality-adjusted life years (QALY). The oral chelating agent deferasirox resulted in a gain of 4.5 QALY per patient at an additional expected lifetime cost of 126,018 USD per patient [8].

Our study revealed the considerable costs for IRCs in patients with hematologic diseases. We used strict criteria and ignored any costs related to a potential loss of social activity. More in the way of comprehensive health and economic studies of IRCs are needed for informed decision-making by patients, clinicians, and health policy makers.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grant no. 800-20070121 from the Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine.

References

- 1.Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997;89:739–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malcovati L, Porta MG, Pascutto C, et al. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in myelodysplastic syndromes classified according to WHO criteria: a basis for clinical decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7594–7603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgna-Pignatti C, Rugolotto S, De Stefano P, et al. Survival and disease complications in thalassemia major. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;850:227–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brittenham GM, Griffith PM, Nienhuis AW, et al. Efficacy of deferoxamine in preventing complications of iron overload in patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:567–573. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modell B, Khan M, Darlison M. Survival in beta-thalassaemia major in the UK: data from the UK Thalassaemia Register. Lancet. 2000;355:2051–2052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02357-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Piga A, et al. A phase 3 study of deferasirox (ICL670), a once-daily oral iron chelator, in patients with beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2006;107:3455–3462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neufeld EJ. Oral chelators deferasirox and deferiprone for transfusional iron overload in thalassemia major: new data, new questions. Blood. 2006;107:3436–3441. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delea TE, Sofrygin O, Thomas SK, Baladi JF, Phatak PD, Coates TD. Cost effectiveness of once-daily oral chelation therapy with deferasirox versus infusional deferoxamine in transfusion-dependent thalassaemia patients: US healthcare system perspective. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:329–342. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]