Abstract

Background

Reflux esophagitis is inversely associated with the presence of atrophic gastritis, and endoscopic grading of atrophic gastritis correlates with histological evaluation. The aim of this study was to investigate the association of the endoscopic grade of atrophic gastritis with gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux.

Methods

A total of 627 patients, who underwent endoscopy and ambulatory 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring, were included in this study. The grade of atrophic gastritis was endoscopically classified into 2 types with the atrophic pattern system: the closed-type (C-type) and the open-type (O-type). We compared the findings from endoscopy and ambulatory pH monitoring for these 2 types.

Results

The O-type was significantly associated with a lower prevalence of reflux esophagitis (p=0.001). All variables showing gastroesophageal reflux in the distal probe were significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (p<0.05). Similarly for the proximal probe, all variables, except the supine time of pH<4, were significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (p<0.05). The frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastropharyngeal reflux disease was in significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (p<0.001, p=0.012, respectively).

Conclusions

Endoscopic grading of atrophic gastritis is easy and is inversely associated with gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux.

Keywords: Atrophic gastritis, Endoscopy, Gastroesophageal reflux, Gastropharyngeal reflux

INTRODUCTION

Risk factors for reflux esophagitis include the presence of hiatal hernia1), transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter2, 3), and impaired clearance of regurgitated gastric contents in the esophagus4). Therefore, esophageal acidity contributes to the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis, with gastritis influencing gastric acid secretion5-7).

There is a higher prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Korea than in Western populations8). H. pylori infection is the major cause of chronic gastritis, which leads to atrophic changes in the gastric mucosa9). Atrophic gastritis may affect gastroesophageal reflux in Korean patients, since reflux esophagitis is inversely associated with the presence of atrophic gastritis10-12).

Since 1969, Japanese physicians have used endoscopy to directly visualize changes in the gastric mucosa of gastritis patients, and they developed an endoscopic grading system for atrophy with using the endoscopic atrophic border13, 14). The atrophic border is the boundary between the antral and fundic glandular territories, which is endoscopically recognized by discriminating between the differences in the color and height of the gastric mucosa. The area of atrophy is pale yellowish in color, with transparent blood vessels, while the area of non-atrophy is homogeneously reddish and smooth. Gastric atrophy, as evaluated with an endoscopic grading system, showed a good correlation with histological evaluation15-17).

The aim of this study was to retrospectively investigate the association of the grade of atrophic gastritis with gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux in patients who underwent both endoscopy and ambulatory 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

We reviewed the medical records and the findings from endoscopy and ambulatory 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring in an unselected group of consecutive patients who were referred to our motility laboratory from January 2004 to June 2006. Six hundred and eighty-nine patients received both of these examinations due to extraesophageal symptoms such as asthma, chronic cough, hoarseness, globus sensation or chronic sinusitis, but 62 patients were excluded due to incomplete medical records or endoscopic information. So, a total of 627 patients were included: 475 men and 152 women, and with a mean age of 50.9±11.8 years.

Assessment by endoscopy

The presence or absence of reflux esophagitis and hiatal hernia were determined, with atrophic gastritis graded by one endoscopist (Kim GH), according to the criteria listed below. The endoscopist was kept "blind" to the information of the ambulatory 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring.

Reflux esophagitis

If esophagitis was present, it was graded according to the Los Angeles classification18).

Hiatal hernia

Hiatal hernia was defined as a circular extension of the gastric mucosa above the diaphragmatic hiatus greater than 2 cm in axial length.

Atrophic gastritis

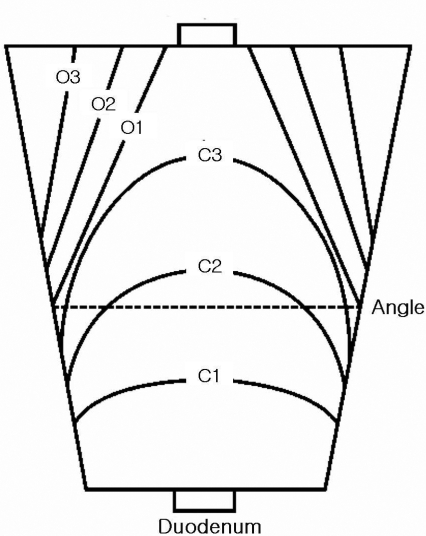

Atrophic changes in the gastric body on endoscopy were diagnosed on the basis of the atrophic area displaying discoloration with or without blood vessels transparency. The grade of atrophic gastritis was assessed endoscopically using the atrophic pattern system described by Kimura et al13, 14). This classification divides the extent of atrophy into a closed type (C-type) and an open type (O-type). The C-type indicates that the atrophic border remains on the lesser curvature of the stomach, while the O-type means that the atrophic border no longer exits on the lesser curvature but extends along the anterior and posterior walls of the stomach (Figure 1). The C-type is subdivided by where the atrophic border crosses: C1, the angulus on the lesser curvature; C2, the lower and middle parts of the corpus; or C3, the upper part of the corpus. The O-type is also subdivided by the location of the atrophic border, which is parallel to the vertical axis of the stomach: O1, on the lesser curvature; O2, on the anterior and posterior walls; or O3, on the greater curvature.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the extension of the endoscopic atrophic border and the patterns of endoscopically diagnosed atrophic gastritis, as represented by Kimura et al14), with permission.

Ambulatory 24-hour dual probe pH monitoring

Prolonged ambulatory pH monitoring was performed immediately after the standard esophageal manometry19), with a single-use, mono-crystalline antimony, dual-site pH probe (Zinetics 24, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) with electrodes placed at the tip and 15 cm proximal to the tip. A cutaneous reference electrode placed on the upper chest was also used. All electrodes were calibrated in buffer solutions of pH 7 and then pH 1. The pH catheter was introduced transnasally into the stomach and then withdrawn back into the esophagus until the electrodes were 5 cm or 20 cm above the proximal margin of the LES (lower esophageal sphincter). Data were collected with a portable data logger (Digitrapper Mark III, Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden) with a sampling rate of 4 seconds. The subjects were encouraged to eat their regular meals, but with restricted intake of food or drink with a pH below 4. All subjects had a diary in which they recorded meal times (start and end), body position (supine and upright), and symptoms, if any. Following the 24-hour monitoring period, the probe was removed, and the data was transferred to a computer for analysis with "Polygram for Windows Release" 2.04 (Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden). In addition, the pH recordings were displayed on a screen for a detailed manual analysis and determination of the temporal relationship of pH declines registered at the two probe sites. For both sites, a decrease in pH below 4 not induced by eating or drinking was marked as the beginning of a reflux episode, which continued until a rise above pH 5. To be accepted as a gastropharyngeal reflux event, the decrease at the proximal probe had to be abrupt and simultaneous with a decrease in the esophagus, or to be preceded by a decrease in pH of a similar or larger magnitude in the distal probe. Thus, acid episodes induced by oral intake, aero-digestive tract residue and secretions, proximal probe movement, or loss of mucosal contact in which the proximal pH decline may precede the esophageal pH drop were not included as gastropharyngeal reflux episodes.

The variables assessed for gastroesophageal reflux in the distal probe were: the total percentage of time the pH was < 4, the percentage of time the pH was < 4 in the supine and upright positions, the number of episodes where the pH was < 4, the number of episodes where the pH was < 4 for ≥ 5 min, the duration of the longest episode the pH was < 4, and the Johnson-DeMeester score20). The variables assessed for gastropharyngeal reflux in the proximal probe were: the total percentage of time the pH was < 4, the percentage of time the pH was < 4 in the supine and upright positions, and the number of episodes where the pH was < 4.

For the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the distal probe, two different aspects were analyzed21, 22): (1) Total reflux time: the total proportion of the recorded time with pH < 4; a value of > 4% was considered abnormal. (2) Number of reflux episodes: the total number of pH episodes with pH < 4 during the recording; a value of > 35 episodes was considered abnormal. For the diagnosis of gastropharyngeal reflux disease in the proximal probe, we considered time at pH < 4 of more than 0.1% total, 0.2% upright, or 0% supine to be pathological. More than 4 reflux episodes was considered pathological23, 24).

Statistical analysis

The data is expressed as medians (ranges) unless otherwise noted. The Student's t-test was used to assess the statistical significance for age and body mass index according to the grade of atrophic gastritis. The Mann-Whitney test was used to assess the statistical significance for the parameters of ambulatory pH monitoring according to the grade of atrophic gastritis. The differences in gender, alcohol drinking, smoking, reflux symptoms, reflux esophagitis, hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastropharyngeal reflux disease, according to the grade of atrophic gastritis, were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 10.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Patient profiles and endoscopic findings according to the grade of atrophic gastritis

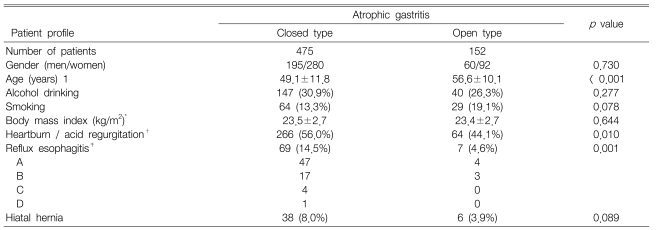

There was no difference in alcohol drinking, smoking, body mass index, or the presence of hiatal hernia according to the grade of atrophic gastritis. The patients with the O-type were significantly older than those with the C-type (p<0.001). The O-type was significantly associated with a lower prevalence of reflux symptoms and reflux esophagitis (p=0.01, p=0.001, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient profiles and endoscopic findings according to the grade of atrophic gastritis

*Mean±SD

†More than 2 days per week

‡Los Angeles classification grade

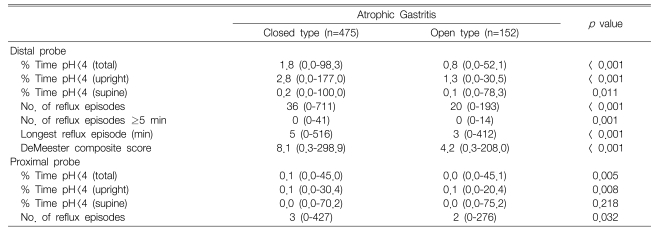

Findings of ambulatory pH monitoring according to the grade of atrophic gastritis

All the variables showing gastroesophageal reflux in the distal probe were significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (p<0.05). Similarly for the proximal probe, all variables, except the supine time of pH < 4, were significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the ambulatory 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring according to the grade of atrophic gastritis

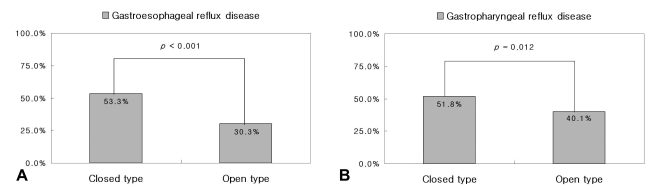

The frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease, as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring, was significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (46/152, 30.3% vs. 253/475, 53.3%, p<0.001). The frequency of gastropharyngeal reflux disease, as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring, was also significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type (61/152, 40.1% vs. 246/475, 51.8%, p=0.012) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Endoscopic findings in the stomach can be largely classified into 2 types using the atrophic pattern system described by Kimura et al13, 14): the C-type and the O-type. The O-type signifies more advanced atrophic gastritis than the C-type. Atrophic gastritis leads to hypochlorhydria, which is inversely related to reflux esophagitis10-12, 25). This is possible due to H. pylori infection, as Koike et al demonstrated that H. pylori infection prevented reflux esophagitis through the induction of atrophic gastritis and reduced acid secretion10). Here, the O-type was also associated with a lower prevalence of reflux symptoms and reflux esophagitis than the less advanced C-type.

All the variables for gastroesophageal reflux in ambulatory pH monitoring were significantly lower in the O-type than in the C-type, including the frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease. These results suggest that atrophic gastritis is inversely related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, including reflux esophagitis. Similarly, variables for gastropharyngeal reflux, including the frequency of gastropharyngeal reflux disease, were also lower in O-type than in the C-type. These results suggest that atrophic gastritis is also inversely related to gastropharyngeal reflux disease, putatively due to decreased gastroesophageal reflux in the O-type. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the association of atrophic gastritis, gastropharyngeal and gastroesophageal reflux disease based on ambulatory pH monitoring.

Probe placement in ambulatory pH monitoring is controversial. The recording of the pH in the hypopharynx is technically difficult, and acid exposure can easily be missed because of the relatively large space within the hypopharynx23). Placement of the proximal probe in or below the upper esophageal sphincter allows more permanent contact with the mucosa during a 24-hour period, which results in fewer artifacts23, 24). We used dual-site pH probes with electrodes placed at the tip and 15 cm proximal to the tip, so we could not choose the exact location of the proximal probe. Yet in most cases (81.5%, 511/627), the proximal probe was located in the upper esophageal sphincter. So, we used the criteria proposed by Smit et al for the diagnosis of gastropharyngeal reflux disease23, 24).

There are some limitations in the present study. First, this study was a retrospective study and the presence of H. pylori was not determined. Also, there might be a potential bias in retrospectively reviewing endoscopic photographs to grade the atrophic gastritis. During endoscopy, we usually took at least 16 photographs, which included nearly the total area of the stomach. In addition, we simplified the grade of atrophic gastritis into 2 types (C-type vs. O-type) and included a large number of cases (627 cases) to lessen the potential bias when reviewing the endoscopic photographs retrospectively. Second, the degree of atrophic gastritis was only evaluated macroscopically by endoscopic findings, without any histological results. However, gastric atrophy evaluated by endoscopy correlates with histological evaluation15-17). Third, we did not evaluate the response to treatment such as proton pump inhibitors, which may differ according to the type of atrophic gastritis.

In clinical practice, endoscopy is the initial investigation of choice for patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease because it can confirm or exclude esophagitis with a high degree of certainty26). Endoscopic grading of atrophic gastritis can be easily learned and adds only a little time and no cost to the endoscopy. Further, provides endoscopists with additional information to correctly diagnose patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and esophagitis.

In conclusion, the endoscopic grading of atrophic gastritis was inversely associated with both gastroesophageal reflux and gastropharyngeal reflux. Endoscopic grading of atrophic gastritis is easy and provides useful information about the status of gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux.

Figure 2.

Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux disease (A) and gastropharyngeal reflux disease (B) as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring according to the grade of atrophic gastritis.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from The Korean Institute of Medicine.

References

- 1.Allison PR. Reflux esophagitis, sliding hiatal hernia, and the anatomy of repair. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1951;92:419–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dodds WJ, Dent J, Hogan WJ, Helm JF, Hauser R, Patel GK, Egide MS. Mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1547–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212163072503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent J, Holloway RH, Toouli J, Dodds WJ. Mechanisms of lower oesophageal sphincter incompetence in patients with symptomatic gastrooesophageal reflux. Gut. 1988;29:1020–1028. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.8.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanciu C, Bennett JR. Oesophageal acid clearing: one factor in the production of reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1974;15:852–857. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.11.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss SF, Calam J. Acid secretion and sensitivity to gastrin in patients with duodenal ulcer: effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1993;34:888–892. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.7.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.el-Omar EM, Penman ID, Ardill JE, Chittajallu RS, Howie C, McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori infection and abnormalities of acid secretion in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:681–691. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haruma K, Mihara M, Okamoto E, Kusunoki H, Hananoki M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori increases gastric acidity in patients with atrophic gastritis of the corpus-evaluation of 24-h pH monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:155–162. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim NY, Kim SW, Kim JG, Kim JJ, Roe IH, Seo JK, Sim JG, Ahn H, Yoon BC, Lee SW, Lee YC, Chung IS, Jung HY, Hong WS, Choi KW. Seroepidemiological study of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic people in South Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:969–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, Takeda H, Mitani S, Miyazaki T, Miki K, Graham DY. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760–766. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90156-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Abe Y, Kato K, Toyota T, Shimosegawa T. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux oesophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330–334. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, Okamoto M, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Shiratori Y, Saito K, Yokouchi K, Omata M. Inverse background of Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen in reflux oesophagitis compared with gastric cancer: analysis of 5732 Japanese subjects. Gut. 2001;49:335–340. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Arakawa T. Association between gastroesophageal flap valve, reflux esophagitis, Barrett's epithelium, and atrophic gastritis assessed by endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura K, Satoh K, Ido K, Taniguchi Y, Takimoto T, Takemoto T. Gastritis in the Japanese stomach. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;214:17–20. doi: 10.3109/00365529609094509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satoh K, Kimura K, Taniguchi Y, Yoshida Y, Kihira K, Takimoto T, Kawata H, Saifuku K, Ido K, Takemoto T, Ota Y, Tada M, Karita M, Sakaki N, Hoshihara Y. Distribution of inflammation and atrophy in the stomach of Helicobacter pylori-positive and -negative patients with chronic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:963–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito S, Azuma T, Murakita H, Hirai M, Miyaji H, Ito Y, Ohtaki Y, Yamazaki Y, Kuriyama M, Keida Y, Kohli Y. Profile of Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin derived from two areas of Japan with different prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Gut. 1996;39:800–806. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Uemura N, Xiao SD, Tytgat GN, Kate FJ. Agreement between endoscopic and histological gastric atrophy scores. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:123–127. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim GH, Kang DH, Song GA, Kim TO, Heo J, Cho M, Kim JS, Lee BJ, Wang SG. Gastroesophageal flap valve is associated with gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:654–661. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1819-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(Suppl 1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnsson F, Joelsson B, Isberg PE. Ambulatory 24 hour intraesophageal pH-monitoring in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1987;28:1145–1150. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.9.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weusten BL, Smout AJ. Ambulatory monitoring of esophageal pH and pressure. In: Castell DO, Richter JE, editors. The esophagus. 4th ed. Philadelphia,: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smit CF, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Devriese PP, Schouwenburg PF, Kupperman D. Diagnosis and consequences of gastropharyngeal reflux. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:440–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smit CF, Tan J, Devriese PP, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Brandsen M, Schouwenburg PF. Ambulatory pH measurements at the upper esophageal sphincter. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:299–302. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199802000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt RH. The relationship between the control of pH and healing and symptom relief in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(Suppl 1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong D, Emde C, Inauen W, Blum AL. Diagnostic assessment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: what is possible vs. what is practical? Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39(Suppl 1):3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]