Abstract

Cystic lymphangioma of the gallbladder is quite a rare tumor with only a few cases having been reported in the literature. We describe here a rare case of cystic lymphangioma of the gallbladder, which was unusual in that the patient presented with biliary pain and an abnormal liver test. Ultrasonography and computed tomography of the abdomen showed a multi-septated cystic mass in the gallbladder fossa and an adjacent compressed gallbladder. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography showed there was no communication between the bile tract and the lesion, and there were no other abnormal findings with the exception of a laterally compressed gallbladder. After performing endoscopic sphincterotomy, a small amount of sludge was released from the bile duct. The histological findings were consistent with a cystic lymphangioma originating from the subserosal layer of the gallbladder. This unusual clinical presentation of a gallbladder cystic lymphangioma was attributed to biliary sludge, and this was induced by gallbladder dysfunction that was possibly from compression of the gallbladder due to the mass.

Keywords: Lymphangioma, Cystic, Gallbladder, Biliary sludge

INTRODUCTION

Intraabdominal lymphangiomas account for less than 5% of all lymphangiomas. The most common location is the mesentery, followed by the omentum, mesocolon and retroperitoneum1-3). Although approximately 60% of these patients are younger than 5 years, a significant number of abdominal lymphangiomas do not manifest until adulthood1). Regardless of the diagnostic modalities used, these facts contribute to the difficulty of diagnosing lymphangiomas at the preoperative stage in adult patients. Lymphangioma of the gallbladder is quite rare with only a few cases being reported in the literature. We recently encountered an interesting case of a cystic lymphangioma of the gallbladder, which was discovered during the work-up for the patient's biliary pain and because of her abnormal liver test, and this is an unusual presentation for this type of lesion. We report here on this case along with a review of the relevant literature.

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with complains of abdominal pain that suddenly developed in the right upper quadrant and also a febrile sensation she felt for the previous 2 days. The patient's prior medical history was unremarkable. She had no history of alcohol consumption or smoking. The patient's body temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate and respiratory rate were 37.2℃, 120/80 mmHg, 80/minute and 20/minute, respectively. A physical examination demonstrated tenderness and a soft palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The laboratory data was as follows: white blood cell count: 13,600/mm3 (82.1% neutrophils, 10.6% lymphocytes and 6.4% monocytes), hemoglobin: 11.6 g/dL, total bilirubin: 1.83 mg/dL (normal range: 0.1 to 1.0 mg/dL), direct bilirubin: 1.15 mg/dL (normal range: 0.1 to 0.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase: 336 IU/L (normal range: <40 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase: 548 IU/L (normal range: <40 IU/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase: 112 IU/L (normal range: <50 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase: 145 IU/L (normal range: 39 to 117 IU/L), and amylase: 38 U/L (normal range: 25 to 125 IU/L). The viral markers (HBsAg, anti-HBs antibody and anti-HCV antibody) were negative. The tumor markers (CEA, CA19-9 and CA125) were also within their normal ranges. Abdominal ultrasonography showed a multi-septated cystic mass in the gallbladder fossa and an adjacent compressed gallbladder (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen also revealed a cystic mass measuring 6×4.5 cm in size in the gallbladder fossa; further, this was also seen on abdominal ultrasonography (Figure 2). There was no bile duct dilatation seen on the above studies. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography was performed to determine if there was any communication between the lesion and the biliary tract, as well as to evaluate for the presence of biliary pathology that could lead to her biliary pain and the abnormal liver test, e.i., microlithiasis or sludge. On cholangiography, there was no communication between the bile tract and the lesion and no abnormal findings of the gallbladder, with the exception of a laterally compressed gallbladder (Figure 3). A small amount of sludge was released from the bile duct after the endoscopic sphincterotomy.

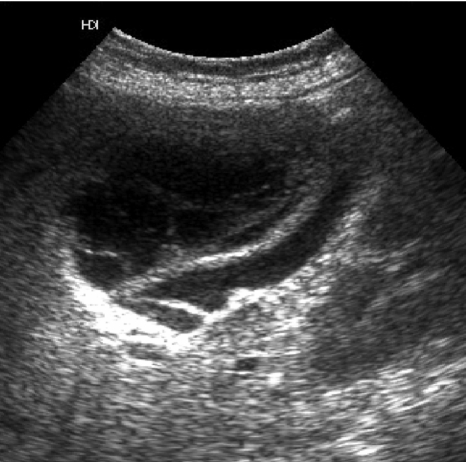

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasonography shows a multi-septated cystic mass and a compressed gallbladder inferior to the cystic lesion.

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT shows the cystic mass originating from the gallbladder fossa.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography demonstrates a laterally compressed gallbladder (arrow).

According to the above imaging studies, the patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A laparoscopic examination revealed the presence of a cystic mass, measuring 5×3×2 cm, attached to the gallbladder wall. The histological examination showed that the cystic lesion originated in the subserosa of the gallbladder and it consisted of variable sized clear spaces that were lined by flat endothelium with some lymphoid tissue in the wall (Figure 4). Yet we have found no evidence of acute inflammation like cholecystitis.

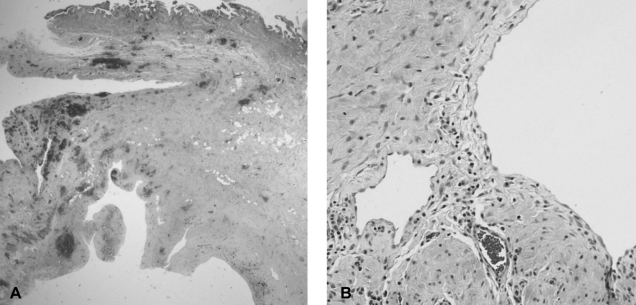

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of the cystic lesion shows that (A) the cyst originated from the subserosal layer of the gallbladder (H&E, ×40). (B) The cyst consists of variable sized clear spaces that were lined by a flat endothelium with lymphoid cells and there were smooth muscles in the cystic wall (H&E, ×200).

Immunohistochemical staining showed that the cells lining the cystic space tested positive for factor VIII-related antigen and there was a negative reaction for cytokeratin. The immunohistochemistry findings supported the diagnosis of lymphangioma rather than mesothelioma. The final diagnosis was a cystic lymphangioma that originated in the gallbladder. Following the surgical resection, the patient recovered well postoperatively and she showed no evidence of recurrence at 6 months follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Lymphangiomas are usually found in the neck and axillary region. An intraabdominal lymphangioma is a rare benign neoplasm that accounts for less than 5% of all lymphangiomas2). Lymphangiomas can arise from the mesentery, retroperitoneum, colon, small intestine, pancreas, omentum, mesocolon and gallbladder1-8). The clinical presentations of intraabdominal lymphangioma are either asymptomatic or this tumor is accompanied by nausea, vomiting and abdominal fullness. The symptoms are due to either pressure on the adjacent structures by the enlarging mass, or to such complications as hemorrhage, infection, perforation, torsion and rupture. However, there are no clinical features that can be used to differentiate intraabdominal lymphangioma from the other intraabdominal masses2-4). Hence, many of the previously reported case were diagnosed incidentally during surgery. The treatment of choice is a complete excision because incomplete removal can lead to a recurrence2).

To the best of our knowledge, there have been only six reported cases of lymphangiomas arising from the gallbladder4-8). The patients had no symptoms in three of these cases. Only a physical examination demonstrated the presence of a mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. In one case, the patient presented with a six month history of chronic right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back. There was no mention of symptoms in the remaining two cases. In the previous cases, there were no reported characteristic symptoms or signs indicating this disease. Unlike the previously reported cases, our patient had acute abdominal pain and a tender mobile mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant, but she also showed an abnormal liver test that indicated an obstructive pattern. Furthermore, biliary sludge was found during balloon sweeping after the endoscopic sphincterotomy. After the surgery, the liver test rapidly normalized. Accordingly, it is believed that the abnormal liver test was due to this small amount of sludge, which was induced by the gallbladder dysfunction resulting from the compression of the gallbladder by the mass. Unfortunately, the gallbladder sludge was not demonstrated on the imaging studies because all the diagnostic procedures used in this study focused only on the cystic mass and not the gallbladder.

Abdominal ultrasonography, CT and MRI imaging have all been used to diagnose abdominal lymphangioma6-10). Ultrasonography typically reveals a simple or multiloculated, anechoic mass. It is helpful to image the internal structure of the mass, particularly the internal septa. CT typically shows a simple or multiloculated cystic lesion with the density of water. The wall of the cyst can be enhanced with using contrast medium. If the lesion is accompanied by bleeding or infections, then the ultrasonography and CT images may show a solid component that is difficult to distinguish from other lesions such as a cystadenoma or a cystadenocarcinoma.

MR imaging of a gallbladder lymphangioma has been reported on7, 8). MRI shows multiloculated cystic lesions with different signal intensities on the T1-and T2-weighted images and these different intensities are due to the different fat and fluid ratios within each cyst. In addition, the septa are enhanced on the delayed phase images, whereas the cystic portions are not.

Based on the histological findings, lymphangiomas are classified as simple, cavernous or cystic2). Our patient had a cystic lymphangioma. The histological characteristics of a cystic lymphangioma include the following: 1) flat endothelial lining of the cyst rather than the cuboidal or columnar epithelium; 2) the presence of lymphoid tissue in the cyst wall; and 3) the presence of smooth muscle in the cyst wall1, 2). The histological findings of our case were consistent with these features. In addition, the cystic mass tested positive to factor VIII-related antigen and it was negative for cytokeratin. A lymphangioma is characterized by an endothelial lining that stains positively for factor VIII-related antigen or CD31. The mesothelioma stains positively for cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen, and this is in contrast to lymphagioma11). The immunohistochemistry studies of our patient also supported the diagnosis of lymphangioma.

We report here on the first case of a cystic lymphangioma of the gallbladder that was associated with biliary sludge. The cystic lymphangioma was diagnosed during the evaluation of the patient's sudden abdominal pain and tender movable mass in her right upper quadrant, and her abnormal liver test.

References

- 1.Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Tumors of lymph vessels. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, editors. Soft tissue tumors. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1995. pp. 679–699. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roisman I, Manny J, Field S, Shiloni E. Intra-abdominal lymphangioma. Br J Surg. 1989;76:485–489. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takiff H, Calabria R, Yin L, Stabile BE. Mesenteric cysts and intraabdominal cystic lymphangiomas. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1266–1269. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390350048010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung JH, Suh YL, Park IA, Jang JJ, Chi JG, Kim YI, Kim WH. A pathologic study of abdominal lymphangiomas. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:257–262. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1999.14.3.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang HR, Jan YY, Huang SF, Yeh TS, Tseng JH, Chen MF. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder lymphangiomas. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1676. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohba K, Sugauchi F, Orito E, Suzuki K, Ohno T, Mizoguchi N, Koide T, Terashima H, Nakano T, Mizokami M. Cystic lymphangioma of the gallbladder: a case report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:693–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JY, Kim MJ, Chung JJ, Park SI, Lee JT, Yoo HS, Kim L, Choi JS. Gallbladder lymphangioma: MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:54–57. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noh KW, Bouras EP, Bridges MD, Nakhleh RE, Nguyen JH. Gallbladder lymphangioma: a case report and review of the literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:405–408. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-0997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyatt RS, Williams ED, Clark M, Gaskins R. CT Diagnosis of splenic cystic lymphangiomatosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1981;5:446–448. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198106000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson AJ, Hartman DS. Lymphagioma of the retroperitonum: CT and sonographic characteristics. Radiology. 1990;175:507–510. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2183287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ordonez NG. Role of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing epithelial peritoneal mesothelioma from peritoneal and ovarian serous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1203–1214. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]