“There is nothing in a physician’s education and training that qualifies him to become a leader”

Mathis, L.L. “The Mathis maxims: lessons in leadership” (1)

LEADERSHIP IN MEDICINE - A NEED AND A VOID

In a recent series of focus groups, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) asked its members for their views on leadership, and whether there was a need to develop leaders in medicine. The results were clear. Canadian physicians told us there is both a need and a void. They told us that while they recognize a need for physicians to assume leadership roles, they do not feel particularly well-equipped to provide the kind of leadership needed in today’s increasingly complex health care environment. They told us that they recognize a need for skills not acquired during their medical training.

The kind of leadership and management skills they want to acquire are ones that are relevant and effective in a wide variety of contexts - their practices, their communities, their professional associations - as well as in ways that can influence public policy. A tall order to fill - and one that arises in part from the nature of the medical profession itself.

Save for a handful of specialties such as public health and epidemiology, medicine focuses on decision-making at the individual physician-patient level. Leadership necessarily involves stepping away from the individual physician-patient relationship and examining problems at a systems level, requiring the ability to view issues broadly and systemically; the ability to maintain what Heifetz called a balcony perspective (2). The balcony perspective is far removed from the cellular perspective, and new medical school graduates are not always familiar with working in this realm.

Physicians also talked to the CMA about how they have typically become involved in leadership roles -some through aspiration, some through inspiration, and many from a desire for new challenges - but most talked about it in terms of happenstance rather than a deliberate choice. Many physicians truly can be considered “accidental leaders.”

Given such a context, and given the CMA’s commitment to providing meaningful opportunities for leadership development, what kind of support can we, as a professional association, provide to doctors who want to develop these non-clinical aspects of their careers?

“You Are Here”

At every shopping mall, there’s a giant colour-coded map with a red “You are Here” arrow to help point our way through these often baffling modern mazes.

If only our professional lives had such a map! Making the choice to enter medicine is often relatively straightforward; many of us consider it a “calling.” But as physicians, we are frequently called upon to make other choices, other decisions about our careers as the years progress.

The impetus for these decisions does not always originate within each individual. Our hospitals, other health care organizations, our communities, service clubs, not to mention various levels of government, all knock on our door requesting our involvement in management and leadership roles. Many perceive that our roles as physicians make us “natural” candidates to be called upon this way. Physicians are viewed as credible leaders, whether they feel so themselves or not.

The decision to take on a leadership role is an important one. It can affect the future course of our professional lives. How can we tell what direction, what choices, are the most appropriate ones to take at the various points of our careers? How do we prepare ourselves?

But before exploring these questions, we should first examine why physicians choose leadership roles.

CHOOSING TO LEAD

As mentioned previously, physicians often find themselves in leadership roles through circumstances. To paraphrase Malvolio in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: some are born leaders, some achieve positions of leadership, while others have leadership thrust upon them.

Why then should we as physicians choose to lead? Why should we not do what we were educated and trained to do - practice medicine?

The answer is found, as Dr. John Waldhousen states, “in our values and our commitments - as physicians, our primary raison d’être is patient care. The welfare of patients, the education of students and residents, and the growth of research knowledge - these are important commitments underlying our profession.”(3)

Our commitments as physicians also carry other implications. We have a social responsibility to speak out on health issues, and this automatically puts us in a position of apparent leadership not only on direct health issues but also on determinants of health.

These commitments and values are a part of us; to an extent they are why we chose to enter the profession in the first place. They are reinforced from the day we begin medical school and they are lived over the years as we practice medicine. It is our professional responsibility to ensure our core values are represented in all important leadership issues, especially in deliberations over the future of health care in Canada.

WHAT IS LEADERSHIP?

Leadership is an intangible quality. It cannot be measured in any traditional sense - on a scale or under a microscope. Fundamentally, leadership is about taking risks. And it is about having the courage of one’s convictions; about the will to act even in the face of powerful conventional wisdom, or strong opposition.

As leadership guru Warren Bennis said: “To an extent, leadership is like beauty. It is hard to define, but you know it when you see it.”(4)

Noted authors and physicians Noren and Kindig provide an important clarification in defining the concept:

“Leadership is not charisma, nor is it the same as management, though both may contribute to leadership practice. Management and leadership have two distinct roles and both are essential to the success of any enterprise. Management means coping with complex organizations and ensuring that things run well, that everyday problems are dealt with, and that there is a steady and continuous performance of the whole. Leadership, on the other hand, involves visioning and motivating others to achieve a preferred vision. It requires dealing with change, often unanticipated, unplanned change - whether it comes from external forces, such as government, or from internal forces, such as new medical technologies and the resultant but unanticipated ethical dilemmas.”(5, 6)

John Kotter, a world-renowned expert on leadership at Harvard Business School, defines leadership by what leaders do: they cope with change, they set direction, they align people to participate in that new direction, and they motivate people (7, 8, 9, 10).

Coping with change is always a challenge, but it is crucial to the survival of the profession - including the personal health and well-being of all physicians. Physician leaders have the responsibility to assist their colleagues in coping with this type of change, but they also have the ability to envision beyond imposed change - to envision their preferred future for the profession and lead others toward this vision.

COLLABORATIVE LEADERSHIP

Physicians have recognized for decades that we are part of a health care team. We recognize that no one member of the team - not the physician, nurse, pharmacist, physiotherapist, or anyone else - can go it alone. We must all work together; we must work with the patient, and for the patient.

This approach mirrors a broader societal move - from the traditional “command and control” form of leadership to a more inclusive style - leadership through influence, not authority; leadership by creating a shared purpose and a common vision, not by using position or power. Today’s leadership focuses not on what leaders are, but on what they do when they are leading. This includes challenging the process, inspiring a shared vision, enabling others to act, modeling the way and encouraging the heart (11).

Individual leaders cannot usually bring about complex change on their own. To provide effective leadership, therefore, the medical community needs to develop and sustain a collective force referred to in the literature as “connected leadership.” The concept emphasizes the importance of relationship building as a basis for leadership - among individuals, among professions, with groups and teams, and among whole organizational systems, cultures and communities. Complex change is facilitated when the strengths and contributions of all stakeholders are openly and genuinely valued.

The theoretical framework for strategic connected leadership is guided by the work of Chrislip (12), Linden (13) and Kotter (7).

CHANGE IMPERATIVES

“In times of change, learners inherit the Earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists.”

Eric Hoffer, The Ordeal of Change (14)

There is much talk about the health ‘system’ as if it were truly a system. It is not. In his book, Prescription for Excellence, Michael Rachlis tells us story after story that demonstrates that the concept of a single health system in Canada is a myth (15). True, there are the components of a system, stewarded by incredibly talented and dedicated professionals. However, in terms of working together as an organized, rationalized, and interconnected whole-health care in Canada certainly falls short. The result is peripatetic change, disparate quality, and an emerging sense that no one - or no group - is truly in charge of this immense, yet immensely vital, ‘system’. Yet no single person and no single group can be, or is, responsible for strategic change.

The nature of leadership in medicine has undergone dramatic changes in recent years. As pressure mounts to drive efficiency, and operate in a cost-effective manner, so the demand for dynamic medical leaders with business acumen grows. However, the solution does not lie in simply injecting a “business” way of thinking into health care organizations. Coping with an evolving health care environment, including continually shifting government agendas, demands active and involved leadership of physicians at every level, if we are to contribute to long-term improvement of health services in this country.

Change in medicine, as in all other fields, is inevitable, and if we as physicians close our eyes to that inevitability, our role as leaders, and our profession, will be diminished.

How do we meet these challenges of change? Does the theory of collaborative leadership work in practice?

Doctors in Canada have shown that it does. For example, both individually, and through the Canadian Medical Association, we have played an active role as leaders in the campaign to reduce waiting times. After the federal and provincial-territorial governments announced their plans to set wait time benchmarks in 5 key areas, the CMA acted quickly, and decisively. The Wait Time Alliance Final Report was released last August, and it outlined maximal medically-acceptable wait times for cancer, heart, diagnostic imaging, joint replacement and sight restoration. It also included sections on better management, measurement and ideas on workforce. By working collaboratively, we have produced wait time benchmarks or performance goals.

The CMA could have tackled the Big 5 treatment areas separately, but that would have meant that we wouldn’t learn the lessons we did by cooperating across specialties. And we wouldn’t be able to transfer the knowledge we gained. Instead, we reached out to national medical specialty societies and formed an unprecedented alliance. We set out to do what our governments committed to doing: establish science-based, maximal medically-acceptable waiting times for care. I am reminded of an old saying: “it’s incredible what you can achieve when you don’t care who gets the credit.”

An analogy that comes to mind here is the carpool. Carpooling has many benefits, not least of which is to cut down particulate matter in the environment, thereby fostering better health. For carpooling to be a success you need to share a destination; share the costs or responsibilities and risks; and share the same values (e.g. personally, I wouldn’t carpool with a smoker). This analogy can be applied to how we can move forward on addressing the access issues facing our health care system. Like the carpool, we need to unite a group of people with the same values who are going to the same place. The group must be willing to share the costs, the risks and most importantly the credit, to bring about the action and change we need.

The power of connected leadership is a compelling reason for physicians to become involved. But how do we best equip ourselves to accomplish these kinds of results? What are the most effective ways for physicians to develop their capacity to contribute to positive change?

DEVELOPING LEADERS

Fundamentals of Physician Leadership

Five fundamental leadership principles are critical to building a better future: 1. recognizing that the work of leadership involves an inward journey of self-discovery and self-development; 2. establishing clarity around a set of core values that guide theorganization as it pursues its goals; 3. communicating a clear sense of purpose and vision that inspires widespread commitment to a shared sense of destiny; 4. building a culture of excellence and accountability throughout the entire organization; and 5. creating a culture that emphasizes the development of leaders and leadership as an organizational capacity. Leadership and learning are inextricably linked.

Wiley W. Souba, MD “Building our Future: A Plea for Leadership” (16)

We need to develop more and better leaders in medicine. There are many leadership development programs and experiences available in the marketplace. What can anyone expect from them? Typical outcomes often include enhanced self-awareness, self-confidence, the ability to view life broadly and systemically, and the ability to maintain Heifetz’ balcony perspective (2):

○ The ability to work in social systems,

○ The ability to contribute and work in a team,

○ The ability to think creatively and adapt evidence-based practices, and

○ The ability to differentiate between solutions that require technical (known but not yet used) solutions and negotiate entirely new solutions as needed.

Where can physicians who are interested in gaining these skills and abilities go, and what does it involve in terms of time and financial commitments? Clinical education is already an exceptionally long and arduous process, so incorporating leadership into that curriculum is problematic at best.

Removing successful practicing physicians from their practice and income for this kind of professional development is an equally difficult proposition, and probably not the best solution in that it takes needed physicians away from their patients. Ongoing clinical practice is needed to maintain their credibility with other practicing physicians in the medical community.

It can be instructive to look at what other organizations and other professions have done to develop effective leaders.

Over the past several decades, corporations recognized that their marketplace survival depended on continuing high levels of management and leadership capacity. Business schools such as the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, the Ivey School of Business, the Queen’s School of Business and the Harvard Business School in the U.S. evolved their curricula to respond to this demand. Almost every major university in North America has followed suit, and today an ever-increasing number of industry leaders are graduates of business schools. Some physicians have chosen to obtain MBAs and similar credentials as well, even though it adds two to three years to their educational period.

These programs are effective in grounding individuals in the fundamentals of management and leadership; however virtually none of the current business school offerings excel in providing the specific context of health care, and the physician’s perspective as a component of their curriculum.

The CMA has chosen to play a dual role here - one in program delivery, one in advocacy. We have been involved for many years in the delivery of management development programs and activities - our annual Leaders’ Forum, workshops like our Physician Manager Institute, the EXTRA fellowship program, conferences and other learning activities, as well as providing formal recognition of the accomplishments of physician leaders through a variety of awards (May Cohen Mentoring Award, Young Physician Leadership Awards, etc.)

We are increasingly playing a second role - one of advocacy. By actively collaborating with business schools, we hope to influence the development and delivery of executive education programs by bringing the physician perspective to them. The potential to influence the educational system can perhaps be one of our most important contributions to leadership development in medicine.

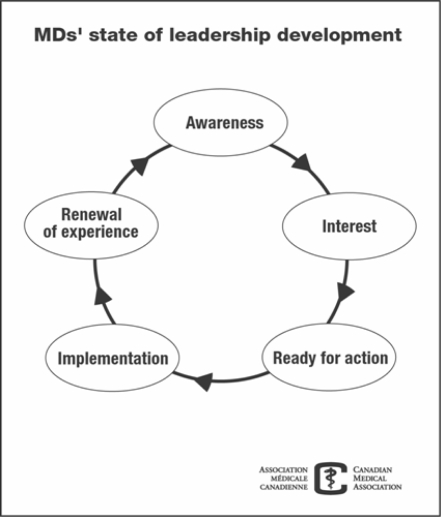

Physician Leadership Development at CMA

Leadership skills can be developed with experience, practice, coaching or mentorship and leadership training. The CMA, through its Office for Leadership in Medicine, recognizes the need to develop leadership within our profession, and the benefits that result. The CMA has been actively involved in physician leadership and management development for almost 25 years. Our vision - “a healthy population and vibrant medical profession” is based on physicians providing leadership to each other and to the broader Canadian population. Flowing from our organizational mandate, the CMA’s mission for leadership development is: “To create an opportunity for all members to realize their full potential as leaders.”

What Defines Physician Leadership?

Our recent investigation of leadership with our members revealed strong support for a CMA focus on leadership. It also provided us with these insights from physicians across Canada:

○ Old models of leadership are irrelevant and unappealing

○ Current programs increasingly do not meet physicians’ needs - we need versatile content as well as flexible and collaborative delivery including non-class room options

○ Focus on the clinical, teaching, research and administration contexts of medicine

○ Put emphasis on action learning principles and appropriate balance among self-reflection, theory, practice and skills

○ Act along the continuum: inspire leaders-to-be, provide opportunities to engage, offer support and celebrate success

○ Provide a complete “menu” of options that would meet the needs of physicians in the diverse roles they fulfill

○ Focus on relevance for most members, with more intense efforts directed at emerging leaders and underrepresented groups

○ Close the information gap between physicians’ aspirations and opportunities to enhance their skills or become involved

○ Tap into expertise among physician leaders

Acknowledging New Ways of Thinking about Leadership

The best practices in leadership development are based on the premise that one should not dissociate learning and doing. We recognize the need to provide opportunities to link skills with issues - create “action learning” opportunities.

Consistent with an action learning approach, the foundation of our approach to leadership development reflects the evolving challenges, and contexts facing physicians.

These challenges and contexts come from a variety of sources - our individual practices, the organizations in which we are involved as leaders, and in the broader context of public policy.

To be effective leaders, we need to move from individual to systems thinking - thinking systemically about the impact of our decisions and our work, over time and beyond individual contexts.

How have these realities affected the approach at the CMA to the development of physician leaders? We have used these insights to develop a set of principles to guide us in our efforts to support the kind of professional development that will be meaningful to our profession.

Leadership Development for the Future

We can only learn about leadership through practising leadership, just as we can only learn how to ride a bicycle by riding a bicycle. Nothing else feels how it feels. No book can prepare a person for leading a team when there is only the foggiest notion of a heading, for asking the right questions rather than appearing to know the answers, or for plugging in to buiness happenings before they happen. In the end we can only learn about it by doing it. This “learning by doing” within a well-thought-through framework is the only way we can turn the leadership-development key and unlock the organization’s leadership potential.

“Action Learning and the leadership development challenge” Peters, J., and Smith, P.A.C. (17)

The CMA is committed to developing what we refer to as a “vibrant medical profession.” This mandate very much depends on developing a critical mass of doctors who are prepared to become involved in leadership roles - roles that can lead and influence the future of our profession, and the future of health care in this country.

In his forward to Hasselbein, Peter Drucker says “The lessons are unambiguous. The first is that there may be ‘born leaders’, but there are surely too few to depend on them” (18).

If Drucker is right, then Porras and Collins have provided a second lesson; leaders for our current and future health care environment need not be high charisma individuals who create followers through personal magnetism (19). They can be people who have developed the skills of thinking and acting “outside the box”, who can confront and challenge old patterns, and spearhead new ones, at any level.

Building physician capacity for leadership in fast-paced, ever-changing environments is crucial. This profession needs men and women with the capacity to lead with knowledge, understanding and wisdom.

My challenge to those of you entering this profession is to get involved in leadership, and if you are already involved, encourage the involvement of other students, residents, physicians as well as other creative front line providers both in problem-solving and in decision-making. Our patients are counting on us!

REFERENCES

- 1.Mathis Larry L. The Mathis Maxims: Lessons in Leadership. Leadership Press; Houston, Texas: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heifetz RA. Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldhousen JMD.Leadership in Medicine Gibbon John H., Jr LectureHershey, PA: 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennis W. The Leadership Advantage in Leader to Leader. San Francisco, CA: Drucker Foundation and Jossey-Bass, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noren J, Kindig David.from an edited version of the Gibbon John H, Jr, Lecture, delivered October 23, 2000, at the ACS Clinical Congress in Chicago, IL, available online: http://www.facs.org/fellows_info/bulletin/waldhausen0301.pdf

- 6.Noren J, Kindig DA. Physician executive development and education. In: LeTourneau B, Curry W, editors. Search of Physician Leadership. Chicago, IL: Health Admin. Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotter JP. Leading Change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. 1995. Mar–Apr.

- 8.Kotter JP. What Leaders Really Do. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotter JP. Winning at Change Leader to Leader. San Francisco, CA: Drucker Foundation and Jossey-Bass, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Challenge:How to Get Extraordinary Things Done in Organizations. Jossey-Bass, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chrislip DD. The collaborative leadership fieldbook. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linden RM. Working across boundaries: Making collaborations work in government and nonprofit organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffer Eric. The Ordeal of Change. New York: Harper and Row; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachlis M. Prescription for Excellence. Harpercollins Canada, Limited; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Souba Wiley W.Building Our Future: A Plea for Leadership Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA: published online; 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters J, Smith PAC. Journal of Workplace Learning Vol. 10, No. 6/7. 1998:284–291. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasselbein F, Goldsmith M, Beckhard R, editors. The Leader of the Future. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porras J, Collins J. Built to Last, Century Hutchinson. London: 1994. [Google Scholar]