Abstract

Nocturnal asthma (NA) is increasing in prevalence, affecting millions of people Genital herpes is a widespread sexually transmitted infection caused by the herpes simplex viruses (HSV). Suppressive valacyclovir therapy has been shown to significantly reduce HSV transmission. The benefits and costs of using valacyclovir to reduce transmission in couples discordant for genital herpes will be analyzed in order to better inform decision-making. By reducing transmission, the physical and psychological harms of living with symptomatic genital herpes will be prevented while saving on certain healthcare costs. However, the large number needed to treat and the low symptomatic rate among infected individuals may outweigh these benefits. The costs of trying to achieve a significant reduction in incidence include the psychological harms of identifying asymptomatic individuals through a large screening program and the economic costs of the antiviral agent and screening. When these issues are weighed, the high economic costs render a program to reduce incidence unfeasible. Nevertheless, it is clinically important to consider the consequences of transmission at an individual level. The specific circumstances that influence the decision to use suppressive therapy are identified.

Keywords: Valacyclovir, Herpes Genitalis, Simplexvirus, Transmission

INTRODUCTION

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection prevalent throughout the world (1). Genital infections with herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV 1 and 2) are common, but infrequently cause noticeable symptoms. The seroprevalence of HSV-2 was 9.1% in 2000 for Ontario (2) while a prevalence of 21.9% among individuals older than 12 years was reported in the United States between 1988–1994 (3). More recently (1999–2004), Xu et al. (4) reported a seroprevalence of 17.0%. A small proportion of infected individuals reported a diagnosis of genital herpes; 9.9% in 1988–1994 and 14.3% in 1999–2004 (4). Thus, most infected individuals are unaware that they are infected but are still able to spread the virus asymptomatically, serving as important transmitters of the virus.

Genital HSV-1 infections can also occur. Although HSV-1 typically causes oropharyngeal lesions and is usually transmitted by non-sexual contact during childhood (5), the virus can cause genital herpes when transmitted by vaginal or oral sex, often without visible lesions (5–8). The lesions of HSV-1 are clinically indistinguishable from those of HSV-2 (9). However, HSV-1 genital herpes infections are less severe and recur less often than HSV-2 (9–12). Howard et al. (2) found a seroprevalence of 51.1% for HSV-1 in 2000 for Ontario. Similarly in the US, HSV-1 was widespread in 1999–2004 (57.7%), but the number of HSV-1 infected individuals reporting genital herpes was 1.8% in this time period (4). HSV-1 comprises 10–15% of all genital herpes cases in the US, although regional variations exist (13). Increasing prevalence of HSV-1 genital herpes has been observed within specific populations. For instance, in an American university student population, the percentage of genital herpes due to HSV-1 increased from 30.9% in 1993 to 77.6% in 2001 (14).

The high prevalence of genital infections due to both HSV-1 and HSV-2 suggests a need to reduce the transmission of genital herpes. In 2003, the US Food and Drug Administration approved an indication for Valtrex (valacyclovir) to reduce genital herpes transmission: “Valtrex reduces the risk of heterosexual transmission of genital herpes to susceptible partners with healthy immune systems when used as suppressive therapy in combination with safer sex practices.” (15) The same indication was approved by Health Canada in 2004 (16). Extensive marketing directed toward patients encourages them to have their HSV serostatus determined (and indirectly encourages valacyclovir use in discordant couples). Both the positive and negative aspects associated with using valacyclovir suppressive therapy to prevent transmission in couples discordant for HSV will be discussed in this paper in an attempt to better inform decision-making.

METHODS

A literature review was performed to determine the costs and benefits of suppressive valacyclovir therapy. In addition, the cost of using valacyclovir to achieve a 30% reduction in the population incidence of HSV-2 genital herpes was calculated (Table 1). Data was used from previously published articles, and all costs were converted to 2000 US dollars. For this analysis, the drug cost required for a coverage level of 30% was determined. At such a high coverage, there would be fewer outbreaks among those receiving suppressive valacyclovir. These savings were conservatively calculated by multiplying the annual cost of genital herpes by the percentage of individuals assumed to have no recurrent symptoms as a result of receiving valacyclovir suppressive therapy. This calculation assumed that all individuals receiving valacyclovir were symptomatic before treatment. Next, the lifetime savings from reducing the annual incidence of HSV-2 by 30% was calculated. The number of years required for these savings to balance the cost of the program was also determined. It was assumed that the 30% reduction in incidence occurred immediately.

Table 1.

Calculating the cost (2000 US dollars) of using suppressive valacyclovir therapy to achieve a 30% reduction in the population incidence of HSV-2 genital herpes.

| Population in USA 2000 (72) | $281,421,906.00 |

| Population with HSV-2 (17%) (4) | $47,841,724.00 |

| 30% of population with HSV-2 | $14,352,517.00 |

| Yearly drug costs per individual | $1,168.30 |

| Drug costs at 30% coverage | $16,768,045,850.00 |

| Yearly lifetime incident cost (51) | $1,800,000,000.00 |

| Yearly savings from preventions | $540,000,000.00 |

| Cost of genital herpes per year (32) | $1,353,405,133.00 |

| Savings due to fewer individuals seeking medical care, assuming 67% of covered individuals will have no recurrence (57) | $272,034,432.00 |

| 3 years of savings | $816,103,295.00 |

| 3 years of drug therapy | $50,304,137,550.00 |

| Net cost | $49,488,034,255.00 |

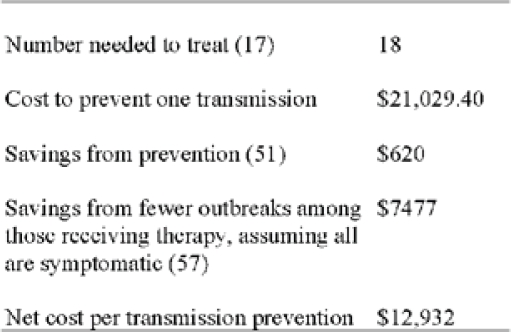

In addition, the cost (2000 US dollars) of preventing a single transmission of HSV-2 genital herpes by using suppressive valacyclovir therapy was calculated (Table 2). Although the number needed to treat to prevent one transmission varies among studies, the figure used in this analysis was considered a conservative estimate. The lifetime savings from preventing the single transmission was calculated using the larger lifetime cost to treat men. Further, there would again be potential savings from a reduction in symptoms among those receiving suppressive valacyclovir therapy. It should also be noted that this simplified analysis is limited since it is based on data from heterogeneous sources, each with its own methodologies and assumptions.

Table 2.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Benefits

The primary benefit of using suppressive valacyclovir therapy is to reduce transmission within discordant couples. Corey et al. (17) found that prescribing valacyclovir to individuals with symptomatic, recurrent HSV-2 infections the acquisition of genital herpes in their discordant partner was reduced from 3.6% in the placebo group to 1.9% in the valacyclovir group (hazard ratio 0.52; 95% confidence interval 0.27–0.99; P = 0.04). Since the absolute reduction was not large, the yearly number needed to treat was 38. Individuals in the valacyclovir group received 500 mg of valacyclovir once daily for eight months. This therapy effectively reduced viral shedding relative to the placebo group. As a result, it reduces transmission when the source partner does not have any recognizable symptoms but is still shedding virus, which is when most transmission events occur (18,19). The potential benefits of using suppressive valacyclovir to reduce transmissions are obvious: reducing the psychological and physical harms of acquiring genital herpes, while lowering the economic costs associated with this infection.

Psychologically, acquiring symptomatic genital herpes can have a significant emotional impact on patients (20–22). Such patients may suffer from social isolation and have difficulty initiating relationships (23,24). In contrast, other studies have shown that appropriate counseling can significantly reduce the psychological harm caused by diagnosing genital herpes (25–27). Receiving genital herpes can also cause anger towards the source partner. Additionally, the source partner may be significantly worried about transmitting genital herpes to their non-infected partner (23). Therefore by reducing transmission, valacyclovir can diminish possible psychological harms, although counseling has been shown to be effective in this regard as well (26).

Potential physical harms due to genital herpes can be prevented with suppressive therapy, assuming that the partner acquires a recognizable, symptomatic infection. Genital herpes caused by HSV-1 recurs infrequently and the frequency decreases over time with a recurrence duration of 7 days (12,28). In contrast, HSV-2 genital herpes recurs more frequently and the rate of recurrence decreases slowly over time with a recurrence duration of 8.5 - 10.1 days (28–30). Local symptoms for HSV-2 infection include pain, itching, and vaginal or urethral discharge (30). Fever, headache, and malaise occur in 39% of men and 68% of females during primary infection (30). Pain during recurrent genital herpes is reported as severe in 11% of patients, moderate in 36%, mild in 48%, and absent in 4% (21). Complications of genital herpes include dysuria, aseptic meningitis, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, transverse myelitis, yeast infections, and extragenital lesions (30).

Economically, reducing the population incidence of genital herpes will decrease such healthcare costs as hospitalizations, clinical examinations, consultations, and tests. Indirect economic costs for patients, such as time off work and traveling costs, will also be avoided (21,23,31,32). Recurrent genital herpes can also lower work effectiveness during severe symptomatic events (21). Szucs et al. (32) performed an analysis of the economic burden of genital herpes in the US for 1996. They estimated the cost of genital herpes to range from $283 million (0.1% of the US health care expenditure) to $984 million with indirect costs totaling an additional $214 million. Of the total cost, 49.7% came from drug expenditures, 47.7% from medical care (consultations and lab testing), and 2.6% from hospital costs. Szucs and colleagues (32) also calculated a cost of $60 000 per case of neonatal herpes and $2 500 for each cesarean section. In summary, reducing transmission will diminish the psychological, physical, and certain economic burdens of symptomatic genital herpes. However, it should be noted that only 14.3% of individuals with HSV-2 develop recognizable, symptomatic genital herpes (4), and as a result, the functional effect of reducing transmission on decreasing this burden is limited.

Costs

There are numerous costs associated with suppressive valacyclovir therapy in couples discordant for genital herpes. First, patients may replace safe sex practices with such therapy. Condoms offer significant, but not complete, protection against HSV-2 (33,34). Condoms also protect against other sexually transmitted infections that an individual in the relationship may have. However, Corey et al. (17) found a similar rate of condom use between the valacyclovir and placebo groups, and regardless of suppressive therapy, condom use remains low among discordant couples (19,33). It appears that suppressive valacyclovir therapy does not change couples’ sexual behaviours, but further studies are required to adequately explore this relationship. Furthermore, it may be suggested that suppressive use of valacyclovir will cause antiviral resistance. Despite a lack of long-term studies, no resistance to this drug has been found for therapy lasting one year (35–37). In long-term studies with acyclovir, resistance is uncommon in immunocompromised individuals (~5%) and rare in immunocompetent individuals (38,39).

Currently, there appears to be little physical harm in taking valacyclovir every day for more than a year in healthy patients (35–37). In patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), there are no data on the safety of therapy lasting more than 6 months (40). Headaches, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and abdominal pain are the most commonly reported adverse effects. Psychologically, taking a drug every day may cause harm or distress. Although patients with recurrent genital herpes prefer suppressive over episodic therapy (22), it is not known how asymptomatic patients would respond to and comply with daily therapy over the long-term.

As previously described, there would be some financial savings with suppressive valacyclovir therapy, but there would also be significant economic costs associated with this program due to drug costs and screening (31,32,41). Firstly, valacyclovir costs $118.47 for 30 tablets of 500 mg, totaling $1441 a year (Canadian dollars, 2008). Another significant cost would be identifying those individuals that have an asymptomatic or unrecognized clinical infection. According to Corey (42), 60% of HSV-2 seropositive individuals have unrecognized symptoms, while 20% are subclinical (asymptomatic) with another 20% being recognized symptomatic. However all three groups have similar frequencies of asymptomatic shedding events (19), defined as detection of HSV on the surface of skin or mucosa in the absence of genital lesions (43). Most individuals with unrecognized symptomatic genital herpes can identify their symptoms with counseling and education (42,44). Additionally, type-specific serologic tests are capable of distinguishing between HSV-1 and HSV-2 (45). The presence of antibodies to HSV-1 alone gives no information on the presence of genital herpes because the site of the infection, oral or genital, cannot be determined (26). Since HSV-1 is very common, genital herpes due to HSV-1 would be difficult to detect without swabbing genital lesions. In addition, the frequency of testing required to identify individuals with genital herpes adds to the cost of screening (45). If testing were recommended with every new sexual partner, there would be considerable strain placed on the healthcare system and the patient.

Moreover, it is predicted that there would be significant psychological harm associated with diagnosing patients with genital herpes who were previously unaware of their infection. Through a large screening program, physicians may actually cause more psychosocial harm to asymptomatic individuals, such as social isolation and reluctance to initiate relationships, than the physical harms these individuals experience (23,24,46,47). However as previously noted, studies have shown that counseling is effective in reducing psychological harm upon diagnosis (25,26). In addition, disclosing the problem to their current partner, who may raise questions of infidelity or past sexual history, may damage or ruin the relationship. Due to the additional economic cost and psychological problems of screening the general population, “it would not be useful. Screening of targeted populations, however, may be appropriate.” (48) That is, a diagnosis would be more important in couples where transmission would be significantly harmful. Such circumstances may include individuals who are at increased risk of HIV infections, HIV positive patients, and patients with a partner with genital herpes (48). By diagnosing these individuals with genital herpes, infected individuals may recognize outbreaks and abstain during such periods. In fact, transmission rates may decrease after source partners disclose (49).

Cost-benefit analyses: population

Current models suggest that suppressive therapy will have a minimal effect on reducing the population incidence of genital herpes at the currently low levels of diagnosis and treatment (50). The coverage level and the duration of suppressive therapy are important factors in reducing the population incidence (50). The coverage level is primarily determined by the proportion of patients diagnosed and the proportion of diagnosed that are receiving therapy. With a coverage level of 3.2% (the current coverage in the US) and 3 years of valacyclovir therapy, it is expected that there would be a 1.8% reduction in new cases after 5 years and a 2.8% reduction after 25 years (50). The percent reduction of new cases increases to 65% with a coverage of 60% after 25 years. According to Williams et al. (50), a coverage rate of 60% is unrealistic, but they suggest that a coverage rate of 30% is theoretically possible and would reduce incidence by 30% after 25 years. Additionally, the duration of suppressive therapy can be increased. At a coverage level of 3.2%, the incidence of HSV-2 infection would be expected to decrease by 3.5% after 25 years with 5 years of therapy, compared to 1.3% with a 1-year therapy program.

The financial cost of administering suppressive valacyclovir over three years to 30% of Americans with HSV-2 genital herpes is approximately $50.3 billion (Table 1). By treating such a large number of patients with suppressive therapy, it is estimated that $816 million would be saved over the three years from reduced outbreaks among infected individuals. Thus, the net cost of a three-year program is $49.5 billion. Using the lifetime cost of an individual with genital herpes (51), the yearly savings from the 30% reduction in incidence is $540 million. Therefore, the savings from the program would balance the cost after 92 years.

Obviously, one must also consider the increased quality of life gained from a decrease in incidence. A conservative estimate of the cost to prevent one HSV-2 transmission is $12,932 (Table 2). This cost would outweigh the benefits gained since a cost of $8,200 per prevention translates to $140,000 per quality-adjusted-life-year gained, which is above the cost effective threshold of $50,000-$100,000 (52). Moreover, these calculations do not include the screening costs that would be necessary to identify asymptomatic individuals and reach the 30% coverage rate. Such screening would be essential to this program because they are the majority of individuals with genital herpes and the main group transmitting the virus (42,46). The compliance may also be lower in the general public than in the trial performed by Corey et al. (17), especially among asymptomatic or unrecognized patients (50).

Cost-benefit analyses: individual

At an individual level in Canada, the financial costs would be that of valacyclovir, $1441 each year, and the cost of screening to determine whether individuals are infected and if couples are discordant. The potential for overuse of expensive serologic testing is enormous. The psychological and physical benefits noted above may convince a symptomatic, discordant couple into asking for valacyclovir to reduce the likelihood of transmission, but in how many instances will valacyclovir reduce transmission? Corey et al. (17) found a 48% reduction in the risk of transmission, but this reduction was from an acquisition risk of 3.6% to 1.9%. Thus, transmission is a rare event without valacyclovir use. Furthermore, when transmission does occur, most people do not develop symptomatic genital herpes. It is essential that patients understand these facts in order to make an informed decision.

Clinically, it is important to consider cases on an individual basis. Specific couple characteristics affect the significance of genital herpes transmission. These factors must be discussed before a discordant couple makes a decision regarding suppressive valacyclovir therapy. For example, prescription may depend on the HSV-1 serostatus of the partner without genital herpes. If this individual has HSV-1, they have a lower probability of developing symptomatic genital herpes upon acquiring HSV-2 (30,53–55).

In addition, the virus type (HSV-1 or HSV-2) of the source partner may be important to determine because each type causes different symptoms and has different modes of transmission. Type 1 (genital) is less likely to cause recurrent symptoms for the partner that acquires symptomatic infection (9–12). Compared to HSV-2, there is less asymptomatic shedding and, therefore, a reduced transmission rate with type 1 genital herpes (11). In addition, oral sex from a partner with a history of oral herpes is a risk factor for HSV-1 transmission (6–8,56). Transmission can occur without lesions because virus in the oropharynx can shed asymptomatically (56). Transmission from oral sex is less likely for HSV-2 because this virus is not as likely to cause an infection in the oropharynx (7,13). Moreover, the manifestation of symptoms in the HSV-2 source partner should be considered. If an individual has many recurrences each year, then it would be more feasible to prescribe suppressive therapy because the individual will receive the added benefit of reduced symptoms. However, suppressive valacyclovir therapy is not typically necessary for HSV-1 genital herpes (12,57), and the effect of valacyclovir on HSV-1 transmission has not been adequately explored. Nevertheless, valacyclovir does decrease the presence of the virus in saliva (58) and has been examined in transmission between wrestlers (59).

Another factor to consider is the duration of the infection in the source partner because infectivity likely decreases with time due to a decrease in shedding (11,33). Most infections occur within a year of contracting the virus. Wald et al. (49) found the mean number of sex acts before transmission was 40 while Mertz et al. (18) found a median number of 24. For HSV-2, asymptomatic shedding was three fold more frequent during the first three months after resolution of primary infection than after these three months (11). It is also important to discuss the number of sexual partners and the nature of the relationship. Between 1999–2004, the seroprevalence of HSV-2 was 39.9% in individuals who had 50 or more lifetime partners compared to 3.8% who had one lifetime partner (4). Transmission is most common in relationships lasting 1–6 months (49).

Transmitting genital herpes may increase the receptive partner’s risk of contracting HIV in the future. The risk of acquiring HIV is approximately three times greater in HSV-2 infected men or women (60). The suggested mechanism for this interaction is likely due to the destruction of the epithelial layer by HSV-2 and attraction of CD4-positive cells (61). This relationship is important for partners that may have a higher risk of contracting HIV due to location, drug use, or sexual behaviours. Additionally, special consideration should be given to a HIV positive, HSV-2 negative partner because HSV-2 reactivation correlates with increased plasma HIV-1 levels (62,63). HSV-2 can increase morbidity and mortality for HIV infected people and may accelerate the course of HIV disease (64). HSV-2 positive, HIV-1 positive individuals may also be more efficient at transmitting HIV than HSV-2 negative individuals (64). Thus, it is important to prevent transmission of HSV-2 to HIV positive individuals (65,66). The interaction between HSV-1 and HIV has yet to be adequately explored (67).

Couples involving a HSV-negative pregnant woman and a HSV positive partner should be made aware that vertical transmission (genital HSV-1 and HSV-2) can be serious for infants, causing death or neurological impairment from disseminated infection of multiple organs and the central nervous system (47,68). Disease of the skin, eyes, or mouth can also occur (68). However, the highest risk of neonatal injury occurs when the pregnant woman acquires either virus type near the time of labor (69). The emotional and financial costs of vertical HSV transmission are obviously significant (31). The duration of the relationship is important, with an 8-fold risk in transmitting HSV-2 in relationships of one year or less compared to relationships existing for more than one year (8). Besides suppressive valacyclovir therapy, counseling, condom use, and abstinence are strategies that should reduce the risk of transmission. However, few discordant couples adopt safer sex practices when educated (70). Similar disseminated infections can occur in immunosuppressed individuals. Thus, such individuals entering relationships with HSV positive partners may benefit from suppressive therapy for the source partner.

Finally, it is important to consider the degree of emotional stress in the source partner regarding transmission and the emotional problems that would likely occur in the non-infected partner upon acquiring genital herpes (71). Some individuals may have a more negative stigma regarding genital herpes than others and acquiring it would be severely damaging to these patients. Such patients should be counseled in an effort to help them understand genital herpes. Nevertheless, some couples’ relationships may be severely affected by this disease and thus may require suppressive valacyclovir therapy more than other couples.

CONCLUSION

The high prevalence of genital infections with HSV-1 and HSV-2 is of great concern and indicates that a solution is required. Nevertheless, suppressive valacyclovir therapy is not a feasible method of reducing the incidence of genital herpes because of the overwhelming economic cost and issues of identifying asymptomatic individuals. Furthermore, the stigma and fear associated with genital herpes only increases the need to educate patients. If a symptomatic individual desires to take suppressive therapy, the physician must inform the patient about the influence of valacyclovir on transmission along with the probability that their partner will become symptomatic. Moreover, patients should consider certain factors that increase the importance of transmission when making a decision, such as the serostatus of the non-infected individual, type of HSV infection, duration of infection, HIV risk, HIV serostatus, pregnancy, and likely degree of resultant emotional stress. Finally, patients need to know about the realistic clinical harms of HSV infections. After better understanding the disease by discussing the above points, patients will be better positioned to make an informed decision regarding the use of prophylactic therapies like valacyclovir.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Kevin Forward for introducing me to this topic and providing me with helpful suggestions and encouragement. Additionally, Dr. Dan Bunbury of the Cape Breton Health Research Centre provided a valuable review of my cost-benefit analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cusini M, Ghislanzoni M. The importance of diagnosing genital herpes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:9–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.suppl_1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard M, Sellors JW, Jang D, Robinson NJ, Fearon M, Kaczorowski J, et al. Regional distribution of antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 in men and women in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(1):84–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.84-89.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, Nahmias AJ, Aral SO, Lee FK, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1105–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710163371601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, McQuillan GM, Lee FK, Nahmias AJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:964–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanberry LR, Jorgensen DM, Nahmias AJ. Herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. In: Evans AS, Kaslow R, editors. Viral infections of humans: epidemiology and control. 4th ed. New York: Plenum Publishers; 1997. pp. 419–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafferty WE, Downey L, Celum C, Wald A. Herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes: impact on surveillance and prevention. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1454–7. doi: 10.1086/315395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Hillier SL. Cunnilingus and vaginal intercourse are risk factors for herpes simplex virus type 1 acquisition in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:84–9. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151414.64297.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardella C, Brown Z, Wald A, Selke S, Zeh J, Morrow RA, et al. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus transmission to pregnant women: a couples study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1891–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, Ashley RL, Corey L. Virologic characteristics of subclinical and symptomatic genital herpes infections. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:770–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509213331205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lafferty WE, Coombs RW, Benedetti J, Critchlow C, Corey L. Recurrences after oral and genital herpes simplex virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1444–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koelle DM, Benedetti J, Langenberg A, Corey L. Asymptomatic reactivation of herpes simplex virus in women after the first episode of genital herpes. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:433–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelberg R, Carrell D, Krantz E, Corey L, Wald A. Natural history of genital herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:174–7. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribes JA, Steele AD, Seabolt JP, Baker DJ. Six-year study of the incidence of herpes in genital and nongenital cultures in a central Kentucky medical center patient population. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3321–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3321-3325.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts CM, Pfister JR, Spear SJ. Increasing proportion of herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes infection in college students. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:797–800. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000092387.58746.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Food and Drug Administration [homepage on the Internet]FDA Updates Labeling of Valtrex [updated 2003 Aug 29; cited 2008 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2003/ANS01250.html

- 16.Notice of Compliance Listings [database on the Internet] Health Canada. - [cited 2008 Jul 10]Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/notices-avis/list/index-eng.php

- 17.Corey L, Wald A, Patel R, Sacks SL, Tyring SK, Warren T, et al. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertz GJ, Schmidt O, Jourden JL, Guinan ME, Remington ML, Fahnlander A, et al. Frequency of acquisition of first-episode genital infection with herpes simplex virus from symptomatic and asymptomatic source contacts. Sex Transm Dis. 1985;12:33–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertz GJ, Benedetti J, Ashley R, Selke SA, Corey L. Risk factors for the sexual transmission of genital herpes. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:197–202. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-3-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carney O, Ross E, Bunker C, Ikkos G, Mindel A. A prospective study of the psychological impact on patients with a first episode of genital herpes. Genitourin Med. 1994;70:40–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel R, Boselli F, Cairo I, Barnett G, Price M, Wulf HC. Patients’ perspectives on the burden of recurrent genital herpes. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:640–5. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romanowski B, Marina RB, Roberts JN. Patients' preference of valacyclovir once-daily suppressive therapy versus twice-daily episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes: a randomized study. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:226–31. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luby ED, Klinge V. Genital herpes: a pervasive psychosocial disorder. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:494–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanderPlate C, Aral S. Psychosocial aspects of genital herpes virus infection. Health Psychol. 1987;6:57–72. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.6.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyai T, Turner KR, Kent CK, Klausner J. The psychosocial impact of testing individuals with no history of genital herpes for herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:517–21. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000137901.71284.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narouz N, Allan PS, Wade AH, Wagstaffe S. Genital herpes serotesting: a study of the epidemiology and patients’ knowledge and attitude among STD clinic attenders in Coventry, UK. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:35–41. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith A, Denham I, Keogh L, Jacobs D, McHarg V, Marceglia A, et al. Psychosocial impact of type-specific herpes simplex serological testing on asymptomatic sexual health clinic attendees. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:15–20. doi: 10.1258/0956462001914841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Corey L. Clinical reactivation of genital herpes simplex virus infection decreases in frequency over time. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:14–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benedetti J, Corey L, Ashley R. Recurrence rates in genital herpes after symptomatic first-episode infection. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:847–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-6-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisman DN, Lipsitch M, Hook EW, 3rd, Goldie SJ. Projection of the future dimensions and costs of the genital herpes simplex type 2 epidemic in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:608–22. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szucs TD, Berger K, Fisman DN, Harbarth S. The estimated economic burden of genital herpes in the United States. An analysis using two costing approaches. BMC Infect Dis. 2001;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wald A, Langenberg AG, Link K, Izu AE, Ashley R, Warren T, et al. Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 from men to women. JAMA. 2001;285:3100–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wald A, Langenberg AG, Krantz E, Douglas JM, Jr, Handsfield HH, DiCarlo RP, et al. The relationship between condom use and herpes simplex virus acquisition. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:707–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker DA, Blythe JG, Miller JM. Once-daily valacyclovir hydrochloride for suppression of recurrent genital herpes. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:103–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel R, Bodsworth NJ, Woolley P, Peters B, Vejlsgaard G, Saari S, et al. Valaciclovir for the suppression of recurrent genital HSV infection: a placebo controlled study of once daily therapy. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:105–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reitano M, Tyring S, Lang W, Thoming C, Worm AM, Borelli S, et al. Valacyclovir for the suppression of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection: a large-scale dose range-finding study. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:603–10. doi: 10.1086/515385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Englund JA, Zimmerman ME, Swierkosz EM, Goodman JL, Scholl DR, Balfour HH., Jr Herpes simplex virus resistant to acyclovir. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:416–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-3-112-6-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reyes M, Shaik NS, Graber JM, Nisenbaum R, Wetherall NT, Fukuda K, et al. Acyclovir-resistant genital herpes among persons attending sexually transmitted disease and human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Ann Intern Med. 2003;163:76–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeJesus E, Wald A, Warren T, Schacker TW, Trottier S, Shahmanesh M, et al. Valacyclovir for the Suppression of Recurrent Genital Herpes in Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Subjects. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1009–16. doi: 10.1086/378416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engel JP. Long-term suppression of genital herpes. JAMA. 1998;280:928–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corey L. The current trend in genital herpes. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21(Suppl 2):S38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koelle DM, Wald A. Herpes simplex virus: the importance of asymptomatic shedding. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45(Suppl T3):1–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.suppl_4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langenberg A, Benedetti J, Jenkins J, Ashley R, Winter C, Corey L. Development of clinically recognizable genital lesions among women previously identified as having “asymptomatic” herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:882–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-11-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rein MF. Should sexually transmitted disease clinics routinely offer serologic testing for genital herpes? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2006;8:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brugha R, Keersmaekers K, Renton A, Meheus A. Genital herpes infection: a review. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:698–709. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urato A, Caughey A. Universal herpes screening in pregnancy: not recommended and potentially harmful to patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e15–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guerry SL, Bauer HM, Klausner JD, Branagan B, Kerndt PR, Allen BG, et al. Recommendations for the selective use of herpes simplex virus type 2 serological tests. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:38–45. doi: 10.1086/426438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wald A, Krantz E, Selke S, Lairson E, Morrow RA, Zeh J. Knowledge of partners’ genital herpes protects against herpes simplex virus type 2 acquisition. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:42–52. doi: 10.1086/504717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams JR, Jordan JC, Davis EA, Garnett GP. Suppressive Valacyclovir Therapy: Impact on the Population Spread of HSV-2 Infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:123–31. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000258486.81492.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisman DN, Lipsitch M, Hook EW, 3rd, Goldie SJ. Projection of the future dimensions and costs of the genital herpes simplex type 2 epidemic in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:608–22. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisman DN. Health related quality of life in genital herpes: a pilot comparison of measures. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:267–70. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koutsky LA, Ashley RL, Holmes KK, Stevens CE, Critchlow CW, Kiviat N, et al. The frequency of unrecognized type 2 herpes simplex virus infection among women. Implications for the control of genital herpes. Sex Transm Dis. 1990;17:90–4. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langenberg AG, Corey L, Ashley RL, Leong WP, Straus SE. A prospective study of new infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1432–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911043411904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu F, Schillinger JA, Sternberg MR, Johnson RE, Lee FK, Nahmias AJ, et al. Seroprevalence and coinfection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in the United States, 1988–1994. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1019–24. doi: 10.1086/340041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spruance SL. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex labialis: excretion of virus in the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:675–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.5.675-679.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brantley JS, Hicks L, Sra K, Tyring SK. Valacyclovir for the treatment of genital herpes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4:367–76. doi: 10.1586/14787210.4.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller CS, Avdiushko SA, Kryscio RJ, Danaher RJ, Jacob RJ. Effect of prophylactic valacyclovir on the presence of human herpesvirus DNA in saliva of healthy individuals after dental treatment. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2173–80. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2173-2180.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anderson BJ. Prophylactic valacyclovir to prevent outbreaks of primary herpes gladiatorum at a 28-day wrestling camp. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koelle DM, Abbo H, Peck A, Ziegweid K, Corey L. Direct recovery of herpes simplex virus (HSV) specific T lymphocyte clones from recurrent genital HSV-2 lesions. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:956–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mole L, Ripich S, Margolis D, Holodniy M. The impact of active herpes simplex virus infection on human immunodeficiency virus load. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:766–70. doi: 10.1086/517297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schacker T, Zeh J, Hu H, Shaughnessy M, Corey L. Changes in plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA associated with herpes simplex virus reactivation and suppression. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1718–25. doi: 10.1086/345771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schacker T. The role of HSV in the transmission and progression of HIV. Herpes. 2001;8:46–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamali A, Nunn AJ, Mulder DW, Van Dyck E, Dobbins JG, Whitworth JA. Seroprevalence and incidence of genital ulcer infections in a rural Ugandan population. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:98–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McFarland W, Gwanzura L, Bassett MT, Machekano R, Latif AS, Ley C, et al. Prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among male Zimbabwean factory workers. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1459–65. doi: 10.1086/315076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strick LB, Wald A, Celum C. Management of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in HIV type 1-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:347–56. doi: 10.1086/505496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:1–13. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.1-13.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown ZA, Selke S, Zeh J, Kopelman J, Maslow A, Ashley RL, et al. The acquisition of herpes simplex virus during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:509–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kulhanjian JA, Soroush V, Au DS, Bronzan RN, Yasukawa LL, Weylman LE, et al. Identification of women at unsuspected risk of primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 2 during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:916–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204023261403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mindel A. Psychological and psychosexual implications of herpes simplex virus infections. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1996;100:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.U.S. Census Bureau [homepage on the Internet]United States Census 2000. [updated 2008 April 24; cited 2008 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html