Abstract

Motivation: For many years, the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) semantic network (SN) has been used as an upper-level semantic framework for the categorization of terms from terminological resources in biomedicine. BioTop has recently been developed as an upper-level ontology for the biomedical domain. In contrast to the SN, it is founded upon strict ontological principles, using OWL DL as a formal representation language, which has become standard in the semantic Web. In order to make logic-based reasoning available for the resources annotated or categorized with the SN, a mapping ontology was developed aligning the SN with BioTop.

Methods: The theoretical foundations and the practical realization of the alignment are being described, with a focus on the design decisions taken, the problems encountered and the adaptations of BioTop that became necessary. For evaluation purposes, UMLS concept pairs obtained from MEDLINE abstracts by a named entity recognition system were tested for possible semantic relationships. Furthermore, all semantic-type combinations that occur in the UMLS Metathesaurus were checked for satisfiability.

Results: The effort-intensive alignment process required major design changes and enhancements of BioTop and brought up several design errors that could be fixed. A comparison between a human curator and the ontology yielded only a low agreement. Ontology reasoning was also used to successfully identify 133 inconsistent semantic-type combinations.

Availability: BioTop, the OWL DL representation of the UMLS SN, and the mapping ontology are available at http://www.purl.org/biotop/.

Contact: stschulz@uni-freiburg.de

1 INTRODUCTION

As high-throughput experimental methods and advanced information technology have impressively increased the amount of data, the resulting information congestion has well-known consequences such as fragmentation of data and knowledge and duplication of research efforts (Stevens, 2000).

Factual information about proteins, genes, diseases and other relevant biomedical entities are increasingly available in structured databases but their dissemination by unstructured, texts i.e. research articles, still prevails. It is estimated that as much as 80% of new scientific facts are communicated only in their original journal publication (Jelier, 2005), the authors relying on a limited group of curators to manually extract, annotate and transfer these facts into the appropriate databases.

Although the pooling of such facts in databases like UniProt (Mulder, 2008) offers clear advantages over the traditional publication process, it would be of great benefit to concentrate all this information in a structured manner in one centralized repository: ongoing research information, peer-reviewed articles, external, authoritative knowledge bases, together with formalizations of the basic kinds of entities and their interrelations in formal ontologies. Several projects [e.g. WikiProteins (Mons, 2008)] try to achieve this goal.

Although resource annotation can rely on huge terminological sources as they have evolved in the last decades, automatic reasoning services for tasks including hypothesis generation and knowledge discovery require sound ontologies, whereas they may produce suboptimal results when based on traditional terminological systems. For this reason, we set out to examine how a formal domain ontology covering the basic kinds of entities in the biomedical domain can replace an informal legacy system. More precisely, we created a mapping between the UMLS SN (McCray, 2003) and BioTop (Beisswanger, 2008), and assessed through this mapping how each resource contributes to the interpretation of the relation between pairs of co-occurring concepts.

The article is organized as follows: after giving an overview of basic concepts like terminology and ontology (Section 2) we describe the resources used, the mapping approach and the evaluation methodology (Section 3). Eventually we present our results and discuss them in the context of related work (Sections 4 and 5).

2 BACKGROUND

We here introduce the basic concepts underlying our work, viz. terminology, ontology and description logics.

2.1 Terminology

Both text mining and manual annotation require some kind of semantic standard. Originally, this issue was supposed to be addressed by controlled vocabularies and terminology systems (DeKeizer, 2000a, b; ISO, 2000), a heterogeneous group of mostly language-oriented artefacts that relate the various senses or meanings of linguistic entities to one another (e.g. by assessing the synonymy between ‘Nephroblastoma’ and ‘Wilms’ Tumor'). Sets of (quasi-) synonymous terms are commonly referred to as ‘concepts’, and in many terminology systems concepts are furthermore related by informal semantic relationships often following vague natural language predicates (narrower than, associated with, etc.). Terminology systems are generally built to serve a well-defined purpose such as document retrieval, resource annotation, the recording of mortality and morbidity statistics or billing. In the medical field, the largest terminological system is the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) (Bodenreider, 2004; UMLS, 2009) in which synonymous terms from different source vocabularies are clustered into concepts, each of which is categorized using a system of semantic types (STs) (McCray, 1995). Today, the UMLS comprises 1.9 million concepts and almost 7 million terms from close to 150 sources.

2.2 Ontology

In reaction to the language- and purpose-oriented and informal approaches to representing a given domain, there has been a growing interest in using formal methods for precisely describing the invariant and language-independent properties of the entities in a domain. In biomedicine, the Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner, 2000) was the pioneer of moving from a purpose-oriented annotation vocabulary to a more principled resource. Similarly, collaborative initiatives have emerged such as the Open Biomedical Ontologies (OBO) Foundry (Smith, 2007), the continuing development of SNOMED CT (SNOMED, 2009), which is increasingly challenged and guided by ontological principles, as well as increasing mutual awareness between the Semantic Web and Life Sciences communities (Ruttenberg, 2007; Sagotsky, 2008).

The term ‘ontology’ stems from analytical philosophy, concerned with the question of ‘what exists?’ (Quine, 1948). It became popular by information sciences, and despite quite contradictory definitions (Kuśnierczyk, 2006) it has increasingly been used to refer to domain representation of various kinds. In order to emphasize the use of a formal language in domain representations, we here subscribe to the concept of formal ontologies (Guarino, 1998) as theories that attempt to give precise representations of the types of entities in reality, of their properties and of the relations among them, using axioms and definitions that support algorithmic reasoning.

2.3 Upper-level ontologies

The purpose of upper domain ontologies is to define the foundational kinds and relations relevant to the entire domain. In the life sciences, this includes classes like gene, protein, cell, tissue, nucleotide, population, organism, diagnostic procedure and biological function, among others. Upper domain ontologies can either be used alone as a source of basic categories (e.g. for the coarse annotation of resources) or as a common reference for more specialized domain ontologies.

In contrast to domain-specific ontologies such as the GO, upper ontologies propose to trade detail for scope by introducing general categories that are the same across all domains. Whether or not this is achievable and desirable has been subject of debate. Nevertheless, several upper-level ontologies have been developed and are being maintained such as BFO1 (Smith, 2007a), DOLCE2 (Gangemi, 2002; Masolo, 2003), SUMO3 (Pease, 2008) or GFO4 (Heller, 2004). More recently, development of application-oriented domain ontologies such as the OBO5 ontologies have led to the proposal of a kind of intermediate-level ontologies, also called top-domain ontologies, such as the Simple Bio Upper Ontology (Rector, 2006), GFO-Bio (Hoehndorf, 2008) or BioTop (Beisswanger, 2008). In contrast to these recent and more theory-laden resources, the pragmatic UMLS SN6, developed 15 years ago, can be regarded as the archetype of a biomedical domain upper ontology (McCray, 2003). Moreover, the SN has already proved its usefulness in providing a consistent categorization of all concepts represented in the UMLS Metathesaurus.

From an upper-level ontology viewpoint, domain upper ontologies play the role of domain ontologies, but from a domain perspective they act as upper ontologies. For example, the placement of BioTop under BFO or DOLCE could be seen as a domain ontology placed under an upper ontology. Conversely, BioTop itself may also play the role of an upper ontology when linked to the Cell Ontology (CO) or the GO.

Different upper-level ontologies not only use different formalisms for their representation but also represent the domain in slightly different ways. As a consequence, the constraints they impose on domain-specific ontologies affect the result of reasoning services based on these upper-level ontologies.

2.4 Description logics

Since the 1980s, the application of formal reasoning on ontology structures has led to various formalisms. Later on, the vision of the Semantic Web (Berners-Lee, 2001) has resulted in a significant standardization of representation languages, formats and reasoning engines.

One of the most noteworthy standards of the Semantic Web was the development of the Web ontology language OWL (Horrocks, 2003) and especially its expressive but still computable subset, OWL description logic (DL). DLs constitute a family of decidable fragments of first-order logic which have a clean and intuitive syntax (Baader, 2007). They come in various flavours, ranging from lightweight to highly expressive ones. The trade-off between expressivity of the logic and computability (and thus, scalability) of its reasoning has to be made in order to properly address the ontology application. Whereas overly inexpressive DL may lead to underspecifications that imply unintended models of the ontology, highly expensive reasoning makes it infeasible from practical viewpoints. OWL DL constitutes a compromise between expressiveness and decidability and is supported by DL classifiers like RACER, Fact++ and Pellet (Haarslev, 2003; Tsarkov, 2006; Sirin, 2007).

Description logics are built around the notions of ‘class’ and ‘relationship’ and follow model-theoretic semantics. Classes such as Heart are interpreted as sets of all instances belonging to that class, i.e. here all particular hearts in the domain. Relationships then are sets of pairs of class instances like hasPart, which extends to all pairs of objects in the domain that are related in terms of parts and wholes. So are all pairs of heart instances with their respective mitral valve instances in the extension of hasPart. We will illustrate DL syntax and semantics through a set of increasingly complex examples, starting with the class Liver, which in our domain extends to all individual livers of all organisms. Analogously, the class BodilyOrgan then extends to all individual bodily organs. When those two statements are put together, we can introduce the key concept of taxonomic subsumption: the class BodilyOrgan forms a superclass of the class Liver, i.e. the former subsumes the latter if and only if all particular livers are also instances of the class BodilyOrgan. In DL notation, this taxonomic subsumption is expressed by the ⊑ operator, e.g. Liver ⊑ BodilyOrgan, and is also known as subtype, subclass or is-a relationship. It is important to stress that this kind of relationship always relates two classes. In contradistinction to this, the instantiation relationship relates an individual entity to some class, e.g. the particular liver of the first author of this article to the class Liver.

Such simple class statements can then be combined by different operators and quantifiers, e.g. the ⊓ (‘and’) operator and the existential quantifier ∃ (‘exists’). For example, InflammatoryDisease ⊓ ∃ hasLocation.Liver denotes all instances that belong to the class InflammatoryDisease and are further related through the relationship hasLocation to some instance of the class Liver. This example actually gives both necessary and sufficient conditions in order to fully define the class Hepatitis:

Hepatitis ≡ InflammatoryDisease ⊓ ∃ hasLocation.Liver.

The equivalence operator ≡ indicates that every instance of hepatitis is necessarily an inflammatory disease that is located in some liver. But through the equivalence operator, one can go in the other direction as well and say that any inflammatory disease that is located in some liver can be classified as hepatitis. In practice, the term on the left and the expression on the right are equivalent.

The constructors introduced so far allow for automated classification and the computation of equivalence, but not for satisfiability checking. This is, however, important, wherever the validity of an assertion is to be assured. For instance, the assertion Immaterial Object ⊑∀ hasPart.ImmaterialObject restricts the value of the role hasPart by using the universal quantifier ∀ (‘only’). It should therefore reject any assertion that states that an immaterial object (e.g. a space) has a material object as part. However, a naïve use of this construct tends to fail. The reason of this is the so-called open world assumption: unless otherwise stated, everything is possible. The following class Strange Object ≡ Immaterial Object ⊓ ∃ hasPart.MaterialObject would remain consistent as long as we do not explicitly state that there is nothing that can be both a material and an immaterial object: Immaterial Object ⊑ ¬ MaterialObject (with ¬ being the negation operator ‘not’). This means that nothing can be equally an instance of either object, i.e. the two classes are disjoint.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 UMLS SN

The provision of an overarching conceptual umbrella over the biomedical domain was the rationale for the development of the UMLS SN (McCray, 2003). A tree of 135 STs forms the backbone of the SN. It is partitioned into the branches ‘entity’ and ‘event’, in which nodes are linked by subclass relations. In addition, the SN contains a hierarchy of 53 associative relationships (e.g. location_of, treats). These relationships are used to form 612 assertions (e.g. Tissue, location_of, Diagnostic Procedure) from which 6 252 additional assertions can be inferred. For each semantic relationship, domain and range are specified in terms of one or more STs. Each concept from the UMLS Metathesaurus is categorized by at least one ST from the SN.

The UMLS SN is a widely used resource in biology and medicine. However, it suffers from some well-known shortcomings (class descriptions that are ambiguous or vague, relatively low granularity, arbitrary divisions) (Schulze, 2004). In view of that we wanted to assess these limitations by making them explicit in an OWL DL representation and to explore alternative upper domain ontologies.

3.2 BioTop

BioTop (Beisswanger, 2008; Schulz, 2006) originated from a redesign and enrichment of the GENIA ontology. Like the UMLS SN, its backbone is constituted by a taxonomic tree, consisting of 334 classes. Its relation hierarchy is populated with 60 relations with domain and range constraints. The main difference from the UMLS SN is given by its use of OWL DL (see Section 3.1). BioTop contains 636 logical axioms among which there are subclass, disjointness and equivalence axioms. The latter (61) enable the computation of additional taxonomic links using DL reasoners. BioTop exhibits links to the upper-level ontologies DOLCE (Gangemi, 2002; Masolo, 2003), BFO (2007a) and the OBO relation ontology (Smith, 2005). Furthermore, it provides mappings to OBO Foundry ontologies (e.g. GO, CO, FMA, ChEBI).

3.3 Mapping

Our main objective of bridging between the UMLS SN and BioTop was to capitalize on the categorization of the UMLS Metathesaurus with SN types on the one hand, and to benefit from the ontologically sound and computationally more sophisticated architecture of BioTop on the other. The aim was to represent the totality of the SN knowledge using BioTop, encompassing the SN types and hierarchical organization as well as the semantic relations with their domain and range restrictions. In order to meet this requirement, an analysis of the UMLS SN semantics in the light of description logics and its transformation into the formalism used by BioTop had to be performed. Technically, the plan was to use a central mapping file, which imported both UMLS SN and BioTop, and served as a store for class and relation equivalences and restrictions. In order to provide mappings for each UMLS SN type, we adjusted the coverage of BioTop wherever justified.

3.4 Assessment methodology

3.4.1 Formative evaluation of BioTop:

We used the logic-driven knowledge reengineering described by Schulz (2001), which employs an iterative approach. Each major ontology redesign (including mapping) step is checked by a description logics reasoner, the results of which are then analysed and corrected under two perspectives: first, the classes tagged as ‘inconsistent’ are identified and the causes are investigated and repaired; second, every time the ontology has reached a consistent state, the logical entailments are analysed for adequacy. Whenever inadequate entailments are encountered, the causes are investigated and fixed.

3.4.2 Consistency of SN-type combinations:

As numerous UMLS Metathesaurus concepts are categorized by more than one ST, their consistency against BioTop should be checked, based on the SN-BioTop map. On the basis of the assumption that combinations of STs linked to Metathesaurus concepts constitute conjunctions, all occurring combinations are identified and then attached to the ontology.

3.4.3 Named entity co-occurrence:

Named entity recognition (NER) is a widely used text mining technique (Park, 2006). A well-known problem in NER is when the word or phrase to be recognized is ambiguous, i.e. it denotes different things. The implementation of the UMLS SN in BioTop offers the possibility to check ambiguous named entities for whether the competing referent concepts are compatible with respect to the SN relations allowed for UMLS STs. We obtained ∼100 million unique pairs from ∼15 million PubMed abstracts that had been mined with the state-of-art named entity (NE) recognizer Peregrine (Schuemie, 2007) to recognize UMLS concepts and Uniprot identifiers referred to within the same sentence. We here consider only the UMLS concept pairs. The task was to manually assess a sample of ∼300 UMLS concept pairs. The curator assessed the plausibility of the linkage between the two concepts in the sentence context. Each co-occurring pair was first checked against the SRSTRE1 table from the SN and alternatively against the mapping ontology, based on the OWL DL implementation of the BioTop/UMLS SN integration.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Mapping of UMLS STs

DL-based ontologies are hierarchies of types (classes) that can be instantiated by particular entities only. According to (McCray, 2002) we can consider the SN as a hierarchy of upper-level classes (regardless of the naming of some of the types that suggest a meta-level interpretation, e.g. the type Functional Concept). The categorization relation (that attaches UMLS Metathesaurus concepts to SN types) can therefore be mostly interpreted as a taxonomic subsumption relation (is-a). Exceptions include geographical locations and a few other true instances, e.g. laws and persons. In these cases the categorization relation is to be interpreted as an instance-of relation.

The mapping was done as follows. First of all, the taxonomic tree of the UMLS SN types was remodelled in OWL (SN.OWL) by expressing the taxonomic subsumption (is-a) as OWL subclasses. No further assumptions were made. Especially, no partitions were introduced, as the source and its documentation do not make any statements as to whether STs are mutually exclusive. On the basis of the textual (SN, BioTop) and the formal (BioTop) definitions available we then attempted to map each ST to BioTop. Lexical mapping criteria were not used. In cases of doubt, domain experts were consulted. The mapping was performed in close collaboration among the authors. At several occasions, problems encountered when accommodating STs in BioTop were discussed in face to face meetings, conference calls and e-mail discussions. In controversial cases other existing ontologies, e.g. OBI, were consulted. For the mapping a new OWL-bridging file was created that referenced both resources with owl:imports statements using the Protégé 4 ontology editor.7 This allowed us to bring together two resources that were out of our direct control and to introduce new assertions linking them.

Mapping the STs of the SN to BioTop the following cases could be distinguished.

4.1.1 Direct match:

The ST is equivalent to a class in BioTop, or the difference is small enough that creating a separate new class alongside an existing one would not be justified; e.g. Animal in BioTop has the exact same meaning as in the SN.

4.1.2 Restriction:

No BioTop class is a straight match for the ST, but it can be defined by restricting an existing BioTop class, e.g. AnatomicalAbnormality is mapped to the expression: OrganismPart ⊓ ∃ bearerOf.PathologicalCondition, where OrganismPart and PathologicalCondition are existing BioTop classes and bearerOf is an existing BioTop relation.

4.1.3 Union:

If the ST cannot be defined by a single class, it corresponds to the union of several classes. Any combination of the previously described types can participate in the union. For example, the SN type Gene or Genome was mapped to the disjunction biotop:Gene ⊔ biotop:Genome.

4.1.4 Out of scope:

The ST cannot be expressed using any of the options above; the immediate solution was to create a new class inside the mapping file itself, defined as the subclass of an existing BioTop class and map the ST to this new class. In the incremental mapping/BioTop redesign process, all ST leaf nodes (but two) introduced this way were recreated in BioTop. The non-matching STs (e.g. ‘daily or recreational activity’) were mapped to a more general BioTop class.

4.1.5 No match:

The ST is regarded meaningless for BioTop in one of the following cases: its definition does not sufficiently differentiate it from its parent, it is too abstract, or it is only included in the SN as a ‘housekeeping’ node in order to group more meaningful child nodes. For example, Chemical Viewed Functionally has a meta-class meaning (it groups UMLS concepts, but is useless as a distinguishing criterion for their individuals) which cannot be represented by BioTop. Leaving the class undefined allows for the existing subsumption hierarchy of the SN to reason up to the nearest parent that does have a mapping, in this case Substance. Most STs on an upper level have imprecise definitions and do not coincide with any BioTop class, e.g. Idea or concept (‘An abstract concept, such as a social, religious or philosophical concept’.), the definition of which seems not plausible to its subtypes, e.g. Geographic Area.

The names, textual definitions and the hierarchical context of SN types created mapping difficulties in many cases. For instance, the ontologically crisp distinction between function and process is mixed up in the SN. So does the type Phenomenon or Process subsume Pathologic Function, which is a parent of, e.g. Neoplastic Process. As a result, some upper-level classes were mapped not to a single class in BioTop but to the union of several classes. An example is Spatial Concept, defined by the union of Body Location or Region, Body Space or Junction, Geographic Area and Molecular Sequence. Others were mapped to quite complex expressions including disjunctions, value restrictions and exclusions.

4.2 Interpretation and mapping of UMLS semantic relations

The treatment of UMLS SN semantic relations turned out to be more complicated thus requiring a two-step approach; they first have to be semantically interpreted and properly built into an OWL DL model before they can be mapped to BioTop. Their simple interpretation as description logics relations (object properties) is semantically problematic as SN relations range over STs (i.e. instantiable classes) whereas object properties range over individual entities. Such an interpretation of concept to concept relations in the light of formal logic has been repeatedly discussed in the recent years (Smith, 2005). For example, five different possible interpretations of SN triples are discussed in Kashyap (2003).

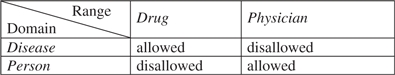

For most UMLS semantic relations there is a quite complex arrangement of domain and range restrictions, in which certain range restrictions are only valid with certain domain restrictions. For instance, the UMLS SN restricts the domain of the treats relation to drugs and physicians, and its range to patients and diseases (among others). However, it does not allow the combination of drug and patient, or health professional and disease.8

We could, of course, ignore this and take simply the union of the extension of the UMLS concepts as the restriction of new BioTop relations that have to be included into the ontology. Thus we would have to accept unintended models, e.g. that a drug treats a person.

We discussed and implemented different solutions how to adequately represent these constraints using OWL DL.

As a first solution, we introduced subrelations, in the following style (again simplified):

treatsMED ⊑ treats (domain: Drug, range: Disease)

treatsPHY ⊑ treats (domain: Physician, range: Person).

In this first step, we obtained a total number of 210 relations (OWL object properties).

However, we have to acknowledge that this is a rather cosmetic solution, because such a model is only able to reject unwanted assertions if the specialized relations but not the general ones are used. Furthermore, by lack of disjointness statements in the class hierarchy it cannot even be rejected that, e.g., something is both a drug and a physician. This is, however, not a fault of the representation language but an underspecification of the UMLS SN.

As a second solution we discussed the following, as it achieves the desired result without the creation of subrelations.

Drug ⊑∀treats.Disease

Physician ⊑∀treats.Person

Together with:

∃treats.Disease ⊑ Drug

∃treats.Person ⊑ Physician

The drawback is here that this solution uses general concept inclusions (GCIs). Although they are part of the OWL DL specifications, they were not supported by our tools.

Both approaches, however, face a severe problem when it comes to the mapping to BioTop, as the latter includes only a relatively low number of relations. Enhancing BioTop by the whole array of SN relations would conflict with its design principle to keep the set of relations small but semantically precise, restricting them to those that are needed for BioTop class definitions. This is not the case with most SN relations: treats, interacts, diagnoses, etc. Instead, BioTop contains, in its Processual Entity branch, already classes such as Treating, Interacting, etc.… which convey the same meaning and can be regarded as reifications.

TreatingPerson ⊑ Action ⊓

∃ has_agent. Physician ⊓ ∃ has_patient. Person ⊓

∀ has_agent. Physician ⊓ ∀ has_patient. Person

TreatingDisease ⊑ Action ⊓

∃ has_agent. Drug ⊓ ∃ has_patient. Disease ⊓

∀ has_agent. Drug ⊓∀ has_patient. Disease

Treating ≡ TreatingPerson ⊔ TreatingDisease

We therefore decided to map—as an alternative approach—the SN relational constraints—expressed as triples—such as

D1 REL R1, D2 REL R2, D3 REL R3,…, Dn REL Rn (Di referring to domain and Ri to range) to an equally uncomplicated DL formula. As a consequence, we do not need to create new DL relations (which would contradict the DL design principles), but simplify the above formula:

REL1 ⊑∀ has_domain. D1 ⊓∀ has_range. R1

REL2 ⊑∀ has_domain. D2 ⊓∀ has_range. R2

REL3 ⊑∀ has_domain. D3 ⊓∀ has_range. R3

…

RELn ⊑∀ has_domain. Dn ⊓∀ has_range. Rn

REL ≡ REL1 ⊔ REL2 ⊔ REL3 ⊔… ⊔ RELn

has_domain and has_range are then mapped to biotop: has_agent and biotop:has_patient.

Of course, the agent/patient reading does not make sense with many spatial or temporal relations. In these cases we extended the map by additional value restrictions.

Finally, there are SN relations that cannot be expressed as relations between particulars because they simply do not relate anything at the level of particulars. The prototypical example is ‘prevent’, such as in the statement ‘contraceptive drugs prevent pregnancy’. On a UMLS concept level it is, without doubt, sensible to express this in a relational form, such as ‘prevents (contraceptive drugs; pregnancy)’.

Such a close-to-human-language assertion on prevention carries several implicit assumptions that must be made clear before expressing it via an ontology; preventing pregnancy does not exclude the possibility of becoming pregnant but it brings about a strong risk reduction. Furthermore, there is both a temporal and a dose association between the drug and the risk. We can therefore rephrase ‘Contraceptive drugs prevent pregnancy’ as follows: ‘The administration of contraceptive drugs of an adequate dose and regularity to a woman reduces her pregnancy risk within a defined timeframe’ or more simply: ‘The administration of contraceptive drugs to a woman reduces her pregnancy risk within a defined timeframe’. We could express this as follows:

PregnancyRiskReductionBySubstanceIntake ⊑

Action ⊓ ∃ has_agent.Substance ⊓

∀has_agent.Substance ⊓

∃ has_patient. (Risk ⊓ (∃ inheres_in. Organism ⊓

∀ inheres_in. Organism)

⊓∀risk_of.Pregnancy)

This digression illustrates the difficulty if not impossibility of an ontologically precise formal reconstruction of seemingly simple close-to-language predicates.

For the semantic relationship mapping we proceeded the following way: all relationships were reified (i.e. expressed as classes) and added as OWL classes using value restrictions on the roles has_agent and has_patient. Those relationships which had a direct correlate in BioTop (i.e. the SN spatiotemporal relationships) were additionally mapped directly to BioTop relationships (object properties). In both cases the domain and range-specific subrelations were accounted for by additional subclasses/subrelations (in analogy to the ‘Treating’ example above). The reification classes were furthermore provided with so-called covering axioms that assure the enforcement of one of the child classes with their restrictions. Again, no mappings were performed for some upper-level relationships (and, accordingly, to upper-level reification classes), for the same reasons as explained for the type hierarchy.

The final result of the mapping of each ST to BioTop yielded 132 equivalence and 19 subclass axioms in the mapping ontology. The OWL reconstruction of the UMLS SN comprised 626 classes and 1530 axioms, and BioTop grew from 200 to 334 classes, 30 to 40 object properties and from 470 to 636 axioms.

4.3 Assessment results

The whole mapping exercise constituted an ideal testbed for the ongoing quality assurance and formative evaluation of BioTop. Because of the constant need of inconsistency checking and resolving, many hidden errors in BioTop were detected, especially faulty disjointness axioms (e.g. Organic Chemical was disjoint from Carbohydrate), unrecognized ambiguities (e.g. Sequence as information entity versus molecular structure) as well as granularity mismatches (e.g. Chromosome as molecule). The maintenance work was, however, very time consuming, totalling at least one person year, divided among five modellers. A significant advance for inconsistency checking and resolution was achieved by the use of a new Protégé add-in that presents precise explanations of entailments in OWL ontologies (Horridge, 2008). Runtime performance, however, proved to be a major drawback. The more axioms are being added (especially negations, disjointness axioms, and inverse properties) the more the performance decreases so that classification time now constitutes a major obstacle in the whole ontology construction and maintenance process.

Nevertheless, it was possible to use the ontology in order to validate an important feature in UMLS, viz. multiple ST categorization. In the 2008 Metathesaurus (totalling more than 1.80 million concepts) release there are 397 different combinations of two to four STs, linked by about 220 000 UMLS concepts. On the basis of the assumption that STY combinations should be interpreted as conjunction, we checked each occurring combination for consistency. The DL classifier recognized 133 combinations as inconsistent, affecting a total of 6116 UMLS concepts. The most frequently occurring unsatisfiable type combination was Manufactured Object with Health Care Related Organization (e.g. Hospital as building versus organization).

The preliminary results of the named entity experiment are, however, less encouraging (Table 1). Because of so many ambiguities, the curator had made a clear assessment of semantic relatedness in only half of the cases. The comparison of the manual classification to the automated one (into ‘true’ and ‘false’) clearly demonstrates the dilemma. The checking against the UMLS SN table STSTR1 shows a certain correlation with the curator's judgment but still produces many false negatives and false positives. BioTop—via the SN and the mapping ontology—rejects extremely few associations.

Table 1.

Named entity co-occurrence results

| Expert judgement: concepts related | Expert judgement: concepts unrelated | |

|---|---|---|

| SN: related | 31 | 22 |

| SN: unrelated | 21 | 71 |

| BioTop: related | 52 | 90 |

| BioTop: unrelated | 0 | 3 |

In order to correctly interpret these results, we emphasize that the question of whether two UMLS concepts are related is not the same as to ask whether their STs exhibit some allowed relationship. For instance, the expert rating for the association between Superoxide reductase (ST: Enzyme) and Aldehyde (ST: Organic Chemical) was negative. Of course, this does not mean that any kind of association between Enzyme and Organic Chemical should de disallowed. On the contrary, these two STs are closely associated, which is not changed by the fact that most random combinations of some enzyme with some chemical are irrelevant.

The low rate of rejections by BioTop demonstrates the problem of the so-called open-world semantics (Baader, 2007), i.e. all models are accepted unless they are explicitly falsified. In the case a description logics ontology is used for this kind of consistency check, the modellers have to be very meticulous in ‘filling the holes’. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that the OWL reconstruction of the idiosyncratic categorization in SN required many disjunctive statements which resulted in a relaxation of the domain and value restrictions. In any way, it is known to be difficult to keep an OWL model ‘water-proof’ in this aspect, and OWL has recently been criticized that it is generally ill-suited for tasks like schema validation (Rajsky, 2008). However, we argue that this is not an inherent but rather a tooling problem, at least for those description logics dialects that support some kind of negation. As a consequence, we performed a thorough fault analysis and could identify and fix several underspecifications that gave rise to unintended models.

5 RELATED WORK

There are many reports in the literature about the conversion of thesauri, frame knowledge bases and ontologies from various representational formats into description logics. Examples are Pisanelli (1998) and Schulz (2001) for the UMLS; Beck (2003), Dameron (2005) and Golbreich (2006) for the Foundational Model of Anatomy; Wroe (2003) and Egana (2008) for the GO and Heja (2007) for ICD-10. What most of these approaches have in common is (i) that the mapping is not straightforward, (ii) it relies on several ontological basic assumptions that are not explicitly stated in the sources, e.g. on disjointness axioms, on the intended meaning and the algebraic properties of relationships and (iii) that not all knowledge conveyed by the sources is expressible in description logics, due to the language constraints.

The UMLS SN was targeted by Kashyap (2003) who concluded that the logical interpretation of the semantic relations in the SN should depend on the application in which the ontology is to be used. More specifically, ontological aspects of the UMLS SN were discussed by Schulze-Kremer (2004). The latter authors acknowledge the importance of the SN for the semantic integration of terminology but spot a number of weaknesses future revisions should address. A major point of criticism is the mixture of concrete with abstract entities, real entities with ‘bauplan’ entities, objects with their roles, functions and processes. This mainly coincides with our mapping experiences as described in Sections 4.1 and 4.2.

6 CONCLUSION

We have described the ongoing development and improvement of a semantic resource, the life science ontology BioTop in the light of the mapping to the legacy UMLS SN. The purpose of this effort is to bring together the large amount of data categorized by the latter with the formal foundation of the former, using emerging standards and tools developed by the Semantic Web community. Semantic and terminological support is especially important for facilitating an opening of the curation process towards a broader community. The alignment of a formal ontology with a relatively informal system of hierarchically ordered categories like the UMLS SN challenges the ontology engineer to formally re-interpret the latter and to overcome its ontological shortcomings. The logical machinery of description logics, implemented in reasoning engines, was an indispensable part of the mapping process, which, ultimately, not only provided a consistent mapping ontology but contributed, by large, to error detection and improvement of BioTop.

We described two assessment experiments. One of them, aiming at satisfiability checking of SN-type combinations yielded good results that revealed hidden ambiguities of UMLS concepts. The other, however, generated rather poor results. It attempted to use the ontology for determining which UMLS concept pairs were closely related to each other. As a result, the mapping ontology rejected very few models, thus supporting the recent critique on the suitability of OWL for schema verification. However, this result also challenged the evaluation scenario: judgements on the relatedness of very specific instances can not be necessarily carried over to judgements at the level of STs. Nevertheless, it was disappointing because the modellers had spent a great effort in partitioning the BioTop ontology in order to antagonize the unwarranted effects of the open-world assumption. This is an issue where more sophisticated tool support for OWL ontology construction and validation is desperately needed, in order to grant formal ontologies and logic-based reasoning a central place in future high-throughput and high-impact life sciences knowledge management technologies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Martin Boeker (Freiburg) and Holger Stenzhorn (Freiburg) for their BioTop maintenance efforts, as well as Robert Hoehndorf (Leipzig) and Alan Rector (Manchester) for fruitful discussions.

Funding: EC STREP project ‘BOOTStrep’ (FP6 – 028099); Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health; National Library of Medicine.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1Basic Formal Ontology.

2Descriptive Ontology for Linguistic and Cognitive Engineering.

3Suggested Upper-Merged Ontology.

4General Formal Ontology.

5Open Biomedical Ontologies.

6Unified Medical Language System.

8For the sake of understandability the example is simplified and does not use the lengthy UMLS SN names.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baader F, et al. Theory, Implementation, and Applications. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. The Description Logic Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- Beck R, Schulz S. AMIA 2003–Proceedings of the Annual Symposium of the American Medical Informatics Association, 687–691. Washington, DC, November 8–12. Philadelphia, PA: Hanley & Belfus; 2003. Logic-based remodeling of the DIGITAL ANATOMIST Foundational Model. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisswanger E, et al. BioTop: an upper domain ontology for the life sciences. A description of its current structure, contents and interfaces to OBO ontologies. Appl. Ontol. 2008;3:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee T, et al. The semantic web. Sci. Am. 2001;284:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenreider O. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;1(Database issue):D267–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dameron O, et al. AMIA 2005–Proceedings of the Annual Symposium of the American Medical Informatics Association. Washington, DC, Philadelphia, PA: Hanley & Belfus; 2005. Challenges in converting frame-based ontology into OWL: the Foundational Model of Anatomy Case-Study; pp. 181–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A. Understanding terminological systems. II: Experience with conceptual and formal representation of structure. Methods Information Med. 2000;39:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Keizer NF, et al. Understanding terminological systems. I: Terminology and typology. Methods Information Med. 2000;39:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egaña Aranguren M, et al. In situ migration of handcrafted ontologies to reason-able forms. Data Knowl. Eng. 2008;66:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi A, et al. Sweetening ontologies with Dolce. In: Gómez-Pérez A, Benjamins RV, editors. Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management: Ontologies and the Semantic Web. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference–EKAW 2002. Berlin: Springer; 2002. pp. 166–181. [Google Scholar]

- Golbreich C, et al. The Foundational Model of Anatomy in OWL: Experience and perspectives. J. Web Semant.: Sci., Services Agents World Wide Web. 2006;4:181–195. doi: 10.1016/j.websem.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino N. Proceedings of FOIS'98. Amsterdam, Trento, Italy: IOS Press; 1998. Formal ontology in information systems; pp. 3–15. June 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Haarslev V, Möller R. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Applications, Products and Services of Web-Based Support Systems, in Conjunction with 2003 IEEE/WIC International Conference on Web Intelligence. Florida, USA: Sanibel Island; 2003. Racer: an OWL reasoning agent for the semantic web. [Google Scholar]

- Héja G, et al. GALEN-based formal representation of ICD10. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2007;76:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller B, Herre H. Ontological categories in GOL. Axiomathes. 2004;14:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hoehndorf R, et al. GFO-Bio: A biological core ontology. Appl. Ontol. 2008;3:219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Horridge M, et al. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on the Semantic Web. Germany: Springer, Karlsruhe; 2008. Laconic and precise justifications in OWL; pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks I, et al. From SHIQ and RDF to OWL: the making of a Web ontology language. Journal of Web Semantics. 2003;1:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Theory and Applications. Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. ISO 1087–1: Terminology work–Vocabulary–Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jelier R, et al. Co-occurrence based meta-analysis of scientific texts: retrieving biological relationships between genes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2049–2058. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyapm V, Borgida A. Representing the UMLS Semantic Network using OWL: (Or “What's in a Semantic Web link?”) In: Fensel D, et al., editors. The SemanticWeb–ISWC. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg; 2003. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kuśnierczyk W. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference FOIS 2006. Baltimore MD, USA: IOS Press; 2006. Nontological (sic!) engineering. Formal ontology in information systems; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Masolo , et al. WonderWeb Deliverable D18 Ontology Library. Infrastructure for the semantic Web. 2003 Available at http://wonderweb.semanticweb.org (last accessed date March 23, 2009) [Google Scholar]

- McCray AT. An upper-level ontology for the biomedical domain. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2003;4:80–84. doi: 10.1002/cfg.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCray AT, Bodenreider O. A conceptual framework for the biomedical domain. In: Green R, et al., editors. The Semantics of Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Dordrecht, Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- McCray AT, Nelson SJ. The representation of meaning in the UMLS. Methods Information Med. 1995;34:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mons B, et al. Calling on a million minds for community annotation in WikiProteins. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder NJ, et al. In silico characterization of proteins: UniProt, InterPro and Integr8. Mol. Biotechnol. 2008;38:165–177. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-9003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JC, Kim J.-J. Named entity recognition. In: Ananiadou S, McNaught J, editors. Text Mining for Biology and Biomedicine. Boston, MA: Artech House; 2006. pp. 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Pease A. The suggested upper merged ontology (SUMO). 2008 Available at http://www.ontologyportal.org/ (last accessed date March 23, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pisanelli DM. Proceedings of the 1998 AMIA Annual Fall Symposium. Philadelphia, PA: Hanley and Belfus; 1998. An ontological analysis of the UMLS Metathesaurus; pp. 810–814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quine O. On What There Is. Rev. Metaphys. 1948;2:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rajsky P. Canonical data model – using industry standard data models. Theory and practice of system integration. 2009 Available at http://www.it.toolbox.com/blogs/system-integration-theory (last accessed date March 23, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Rector A, et al. Simple bio upper ontology. 2006 Available at http://www.cs.man.ac.uk/∼rector/ontologies/simple-top-bio (last accessed date March 23, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ruttenberg A. Advancing translational research with the Semantic Web. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8(Suppl. 3):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-S3-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagotsky JA, et al. Life Sciences and the web: a new era for collaboration. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:201. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuemie M, et al. Proceedings of the Biocreative 2 Workshop. Madrid, Spain: Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas; 2007. Peregrine: lightweight gene name normalization by dictionary lookup; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Hahn U. Medical knowledge reengineering – converting major portions of the UMLS into a terminological knowledge base. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2001;64:207–221. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, et al. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Formal Ontology in Information Systems (FOIS 2006). Baltimore, MD: 2006. From GENIA to BioTop – towards a top-level ontology for biology; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Kremer S, et al. Revising the UMLS Semantic Network. 2004 Available at http://www.ontology.buffalo.edu/medo/UMLS_SN.pdf (last accessed date March 23, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Sirin E. Pellet: a practical OWL-DL reasoner. Web semantics: science, services and agents on the world wide web. Software Engineering and the Semantic Web. 2007;5(2):51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. The OBO foundry: coordinated evolution of ontologies to support biomedical data integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1251–1255. doi: 10.1038/nbt1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, Grenon P. Basic formal ontology. 2007 Available at http://www.ifomis.uni-saarland.de/bfo/ (last accessed date March 23, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, et al. Relations in biomedical ontologies. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNOMED Clinical Terms (2009). Copenhagen: International Health Standards Development Organisation. Available at http://www.ihtsdo.org (last accessed date April 21, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Stevens R, et al. Ontology-based knowledge representation for bioinformatics. Brief. Bioinform. 2000;1:398–416. doi: 10.1093/bib/1.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsarkov D, Horrocks I. FaCT++ description logic reasoner: system description. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2006;4130:292–297. [Google Scholar]

- UMLS. Unified Medical Language System. MD: National Library of Medicine, Bethesda; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wroe CJ, et al. A methodology to migrate the gene ontology to a description logic environment using DAML+OIL. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2003;8:624–635. doi: 10.1142/9789812776303_0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]