Abstract

Functional relationships between proteins that do not share global structure similarity can be established by detecting their ligand-binding-site similarity. For a large-scale comparison, it is critical to accurately and efficiently assess the statistical significance of this similarity. Here, we report an efficient statistical model that supports local sequence order independent ligand–binding-site similarity searching. Most existing statistical models only take into account the matching vertices between two sites that are defined by a fixed number of points. In reality, the boundary of the binding site is not known or is dependent on the bound ligand making these approaches limited. To address these shortcomings and to perform binding-site mapping on a genome-wide scale, we developed a sequence-order independent profile–profile alignment (SOIPPA) algorithm that is able to detect local similarity between unknown binding sites a priori. The SOIPPA scoring integrates geometric, evolutionary and physical information into a unified framework. However, this imposes a significant challenge in assessing the statistical significance of the similarity because the conventional probability model that is based on fixed-point matching cannot be applied. Here we find that scores for binding-site matching by SOIPPA follow an extreme value distribution (EVD). Benchmark studies show that the EVD model performs at least two-orders faster and is more accurate than the non-parametric statistical method in the previous SOIPPA version. Efficient statistical analysis makes it possible to apply SOIPPA to genome-based drug discovery. Consequently, we have applied the approach to the structural genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to construct a protein–ligand interaction network. The network reveals highly connected proteins, which represent suitable targets for promiscuous drugs.

Contact: lxie@sdsc.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Evolutionary and functional relationships between proteins can be reliably inferred by the comparison of their sequences and benefits from a well-understood extreme value distribution (EVD) model that can be applied on a large scale (Altschul et al., 1997; Claverie, 1994; Levitt and Gerstein, 1998; Pearson, 1998). When the sequence similarity is not statistically significant, remote protein relationships can often still be detected by global 3D structure comparison since protein structures are more conserved than protein sequences. Although a rigorous statistical model for global structure comparison is difficult to derive, it has been empirically shown that the structural comparison score follows an EVD if a summarized structural alignment score, rather than a root mean square deviation (RMSD), is used (Levitt and Gerstein, 1998). Recently increasing evidence suggests that proteins can be related by their ligand-binding sites even when global sequence or structure similarity cannot be detected (Gerlt and Babbitt, 2001; Scheeff and Bourne, 2005; Weber et al., 2004; Xie and Bourne, 2008). Consequently mapping of protein space by ligand-binding site similarity will increase our understanding of divergent and convergent evolution and the origin of proteins (Gerlt and Babbitt, 2001; Gherardini et al., 2007; Scheeff and Bourne, 2005; Xie and Bourne, 2008), and improve our ability to predict unknown protein functions (Binkowski et al., 2003; Dobson et al., 2004; Kinoshita et al., 2001; Kinoshita and Nakamura, 2003; Kuhn et al., 2006; Laskowski et al., 2005; Pazos and Sternberg, 2004; Powers et al., 2006; Schmitt et al., 2003; Tseng et al., 2009). Moreover, recently we have shown that such ligand–binding-site mapping can contribute to the design of pharmaceuticals through the detection of off-targets (Kinnings et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2007).

A number of algorithms have been developed for the comparison of ligand-binding sites (Artymiuk et al., 1994; Barker and Thornton, 2003; Binkowski et al., 2003; Brakoulias and Jackson, 2004; Cammer et al., 2003; Campbell et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005; Green, 2006; Ivanisenko et al., 2004; Jambon et al., 2003; Kinoshita et al., 2001; Kinoshita and Nakamura, 2003; Kleywegt, 1999; Laskowski et al., 2005; Mardia et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2004; Morris et al., 2005; Pickering et al., 2001; Schmitt et al., 2003; Shulman-Peleg et al., 2004; Siggers et al., 2005; Stark and Russell, 2003; Stark et al., 2003; Torrance et al., 2005; Wallace et al., 1997; Zhang and Grigorov, 2006). Using these algorithms, the similarity between two sites is measured using geometric criteria such as RMSD (Russell, 1998; Stark et al., 2003), spherical harmonic expansion (Morris et al., 2005), residue conservation based on an amino-acid substitution matrix (Binkowski et al., 2003; Laskowski et al., 2005) or a Tanimoto Index (TI)-like measurement that is based on residue clusters (Stark and Russell, 2003; Zhang and Grigorov, 2006), atom types (Jambon et al., 2003; Schmitt et al., 2003) or surface electrostatic potentials (Kinoshita et al., 2001). Correspondingly, five types of probabilistic models have been developed to assess the statistical significance of the ligand–binding-site match. Russell (Russell, 1998) and Binkowski et al. (Binkowski and Joachimiak, 2008) build a score look-up table from millions of random matches. Stark et al. have developed a geometrical model to estimate a priori significance of RMSD in atomic positions (Stark et al., 2003). Davies et al. extend the TI-based measurement to a Poisson Index (PI) model that relies on a well-defined theoretical framework of Poisson processes (Davies et al., 2007). It has been shown that the PI model significantly outperforms the TI model. Unlike the above two models that only use crude classifications of residues, atomic types or surface properties, Binkowski et al. (Binkowski et al., 2003) and Laskowski et al. (Laskowski et al., 2005) assess the significance of the similarity by quantitatively measuring the ligand–binding-site sequence alignment based on amino-acid substitution matrices. Chen et al. have devised a non-parametric statistical model that in theory can be applied to any scoring function (Chen et al., 2005) but still requires a predefined template site.

We have developed a new sequence-order-independent profile–profile alignment (SOIPPA) algorithm for ligand-binding-site comparison (Xie and Bourne, 2008). SOIPPA has several features that distinguish it from other existing methods. Prior knowledge of both the location and the boundary of the ligand-binding site is not required. Instead, whole proteins are scanned to find the most similar local patch in the spirit of local sequence alignment such as the Smith–Waterman algorithm (Smith and Waterman, 1981). This feature makes SOIPPA suitable for practical problems since typically the boundary of the ligand-binding site is not clearly defined and depends on the bound ligand. In addition, two globally dissimilar ligand-binding sites may share a similar sub-site to accommodate the same molecular moiety even though the overall ligand is different and can be detected by SOIPPA. SOIPPA integrates geometric, evolutionary and physical information into a unified similarity score akin to a sequence alignment score. Stated another way, SOIPPA uses a quantitative measure of residue conservation as found in an amino-acid substitution matrix or more sensitive profile–profile score. However, unlike conventional sequence alignment, the SOIPPA alignment is sequence order independent as its name suggests; a necessary requirement when comparing local-binding sites, since the associated functional residues may not follow the same sequence order in different proteins.

The local alignment and the scoring function used by SOIPPA impose a new challenge in assessing the statistical significance of the binding-site comparison. Most of the existing statistical models cannot be applied because they only take into account the matching of a fixed number of vertices between two sites. Moreover, the matching vertex algorithms only use a crude classification of amino-acid conservation or atom physical properties rather than the quantitative measurement used by SOIPPA. Although the Binkowski–Laskowski model uses the summarized quantitative residue conservation score, it only considers the sequence order dependent case. A non-parametric statistical-based method has been proposed previously (Binkowski et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005; Xie and Bourne, 2008; Xie et al., 2007). However, it requires a fixed size for the template ligand-binding site. In addition, at least hundreds of additional comparisons are needed to derive the background distribution. As a result, it cannot be scaled to a genome-wide study of binding-site comparisons.

Here, we report a new statistical model that is nearly identical to the well-known EVD used in sequence and structural alignment. We find that the score of the local-site matching using SOIPPA also follows an EVD, but independent on the sequence order and the predefined ligand-binding site. Benchmark studies show that the new statistical model performs at least two-orders faster than the previous non-parametric method without sacrificing database search sensitivity and specificity. The unified statistical framework for sequence, structure and ligand-binding site comparison makes it possible to study protein relationships at multi-scales. The algorithm proposed in the article has been implemented in software SMAP v1.4, which is available from http://funsite.sdsc.edu.

Owing to scalability and robustness of SOIPPA and the EVD model, we have successfully applied SMAP to drug discovery, including elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of drug side-effects and repurposing of safe pharmaceuticals to target different pathways (Kinnings et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2007). Here, we report the construction of a structural genome-wide protein interaction network of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using SMAP. The network provides a first step in rationally designing multi-target therapeutics to combat drug-resistance tuberculosis.

2 METHODS

2.1 Representation of protein structures

We represented protein structures using Delaunay tessellation of Cα atoms that are characterized by geometric potentials (Xie and Bourne, 2008). The regular tessellation generates a mesh surface surrounding the Cα atoms. A normal vector that is perpendicular to the mesh surface can be assigned to each Cα atom. The regular tessellation of the protein structure also encodes a graph representation in 3D space. The nodes of the graph are the Cα atoms. The connections in the regular tessellation form the edges. We used the graph representation of the structure in the ligand-binding site comparison described below.

2.1.1 Local protein sequence order independent alignment

We aligned two proteins using the sequence order independent profile–profile alignment (SOIPPA) algorithm (Xie and Bourne, 2008). The algorithm is based on finding the maximum- weight common sub-graph (MWCS) between two encoded protein graphs. A weight is assigned according to the chemical similarity or evolutionary correlation of the associated sites. In this article, the McLachlan chemical similarity matrix (McLachlan, 1972) and BLOSUM45 substitution matrix (Henikoff and Henikoff, 1992) were used for chemical similarity and for evolutionary correlation, respectively. The MWCS is implemented with a branch-bound algorithm (Kumlander, 2004; Ostergard, 2001; Ostergard, 2002).

2.2 Scoring function for ligand-binding site similarity

After two structures are superimposed according to the alignment, the binding-site similarity is measured using a Gaussian density function Sij as follows:

| (1) |

where Mij is the residue similarity determined by the substitution matrix between two residues of proteins i and j, respectively. Here the McLachlan physical similarity matrix (McLachlan, 1972) and BLOSUM45 substitution matrix were used (Henikoff and Henikoff, 1992). paij and pdij are determined as follows:

| (2) |

|

(3) |

where αij and dij is the angle and the distance between the two Cα atoms, respectively. The angle is calculated from the inverse cosine of the dot product between the normal vectors of the two Cα atoms. The parameters used in the calculation are empirical and not optimized.

2.3 Statistical model

To derive a background distribution of raw scores for binding-site similarity, 36 structures with different CATH architectures were randomly selected from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al., 2000; Deshpande et al., 2005). These chains are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

PDB chains used for deriving the background distribution for SOIPPA score statistics

| PDB ID | Chain ID | CATH ID |

|---|---|---|

| 1YOZ | A | 1.10.3200 |

| 1YO7 | A | 1.20.1440 |

| 1B3U | A | 1.25.10 |

| 1PPR | A | 1.40.10 |

| 1AGM | A | 1.50.10 |

| 1MVF | C | 2.10.260 |

| 1C3K | A | 2.100.10 |

| 1N7V | A | 2.105.10, 2.60.330, 2.70.250 |

| 1GEN | A | 2.110.10 |

| 1GYD | A | 2.115.10 |

| 1A14 | A | 2.120.10 |

| 1A0R | A | 2.130.10 |

| 1AOM | A | 2.140.10 |

| 1P9H | A | 2.150.10 |

| 1EWW | A | 2.160.10 |

| 1T2R | B | 2.170.260 |

| 1MKN | A | 2.20.60 |

| 1YDU | A | 2.30.240 |

| 1XKC | A | 2.40.320 |

| 1KSA | A | 2.50.10 |

| 1ABR | B | 2.80.10 |

| 1B2P | A | 2.90.10 |

| 1VKB | A | 3.10.490 |

| 1BP1 | A | 3.15.10 |

| 1YBE | A | 3.20.140 |

| 2SIC | C | 3.30.350 |

| 1Y0K | A | 3.40.1540 |

| 1J7G | A | 3.50.80 |

| 1J5U | A | 3.55.10 |

| 2PVA | A | 3.60.60 |

| 1A2N | A | 3.65.10 |

| 1AXC | A | 3.70.10 |

| 1BWD | A | 3.75.10 |

| 1A4Y | A | 3.80.10 |

| 1YB5 | A | 3.90.180 |

| 4MT2 | A | 4.10.10 |

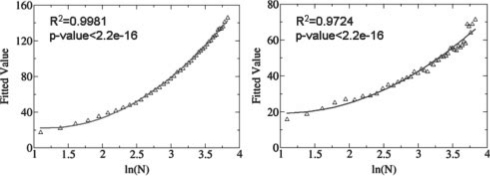

The residues from the above structures were randomly shuffled 100 times to construct a total of 3600 structural models. Two structural models whose templates belong to different CATH classes were aligned using the SOIPPA algorithm. In the end, a total of 8 46 711 alignments were generated and used in the model fitting. The alignment length ranges from 3 to 63. As shown in Figure 1, the alignment scores for given alignment lengths fit EVD:

| (4) |

where:

| (5) |

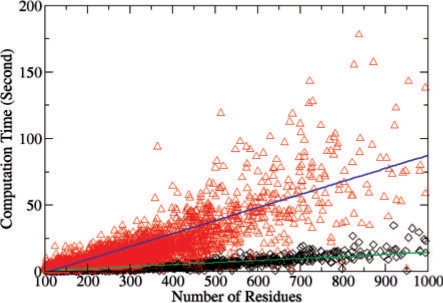

where S is the raw SOIPPA similarity score. As shown in Figure 2, μ and σ are fitted to the logarithm of N, which is the alignment length between two proteins:

| (6) |

| (7) |

Six parameters a, b, c, d, e and f are derived from the linear regression of the above formula using R (http://www.r-project.org), resulting in a = 17.242, b = −40.911, c = 46.138, d = 5.998, e = −12.370 and f = 25.441 for the BLOSUM45 matrix and a = 5.963, b = −15.523, c = 21.690, d = 3.122, e = −9.449 and f = 18.252 for the McLachlan similarity matrix, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fitting of the square of the SOIPPA raw scores to an extreme value distribution (EVD) for alignment lengths N of 5, 15, 25 and 35, respectively. The EVD is determined by two parameters μ and σ, which are estimated from linear regression of the rearrangement of Equations 4 and 5 (see text and Fig. 2) as S2 = μ + σ(–ln(–ln(1−-P))).

Fig. 2.

The derived parameters μ and σ that determine a unique extreme value distribution (EVD) for a specific alignment length can be fitted to a quadratic function based on the logarithm of alignment length.

2.4 Benchmark data

The benchmark data used in this article is the same as that from a previous study (Xie and Bourne, 2008). In brief, a set of 247 protein monomer chains, which are bound to the following ligands, ATP, ADP, NAD, FAD, SAM and SAH, were selected as positive controls from the RCSB PDB (Berman et al., 2000; Deshpande et al., 2005). One hundred and one protein complex structures not bound to a ligand-containing ribose, adenine, flavin and nicotinamide were extracted from the PDB as negative controls. The sequence identity between each pair of chains was below 30%.

2.5 Performance evaluation

We evaluated sensitivity and specificity of the ligand-binding site search using a true and false positive rate as defined in the previous article (Xie and Bourne, 2008):

|

Time complexity of the algorithm was evaluated by querying 5000 non-redundant PDB chains to two randomly selected structures (PDB id: 1AU1 and 1ZY9). Their chain lengths are 166 and 564, respectively. The computation was executed on a personal computer with an Intel Xeon 3.00 GHz CPU.

2.6 Construction of the protein–ligand interaction network of M. tuberculosis

We first download the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain from the TB Database (www.tbdb.org). All available non-redundant M. tuberculosis structures were extracted from the PDB. These structures cover 232 out of 3999 open reading frames in the whole M. tuberculosis genome. We compared the biological units of the 232 structures with each other using SMAP; a total of 232 × (232 – 1)/2 = 26 796 pairs were generated. A predicted M. tuberculosis protein–ligand interaction network is constructed. In the network, the node is one of the 232 structures. An edge is formed if SMAP P-value is less than 1.0E–7 for the pair-wise alignment between two structures. The nodes are ranked based on their connectivity to others from high to low.

2.7 Determination of the druggability of the predicted M. tuberculosis targets

The druggability of the top 18-ranked proteins was assessed by using them as queries to scan a set of 305 protein–drug complex structures. The drug-binding structures were extracted from SuperTarget (Gunther et al., 2008). The binding site in the M. tuberculosis target was predicted from the alignment between the target and the drug-binding site. Finally, the drug was docked to the predicted drug-binding site using the protein–ligand docking software eHiTs (Zsoldos et al., 2007).

3 RESULTS

3.1 EVD for the SOIPPA alignment score

We have improved both the speed and accuracy of our original ligand-binding site similarity search algorithm (Xie and Bourne, 2008) using the new statistical model. Previously the statistical significance of the ligand-binding site similarity was estimated based on a non-parametric statistical method (Xie and Bourne, 2008). It required hundreds of additional comparisons for each binding site to establish a background distribution. Here, we report a unified statistical framework similar to that used in sequence and structure comparison (Levitt and Gerstein, 1998) where the significance of binding-site similarity can be estimated at least two orders of magnitude faster than for the original non-parametric method.

We find that the probability density distribution of the square of the raw binding-site similarity score fits EVD that is only dependent on the alignment length, as shown in Figure 1. The EVD is uniquely determined by two parameters μ and σ (see ‘Methods’ section), which can be fitted to the logarithm of the number of aligned residues (Fig. 2). Thus the P-value of the observed similarity can be computed analytically from the given distribution for any pair of ligand-binding sites with any number of residues.

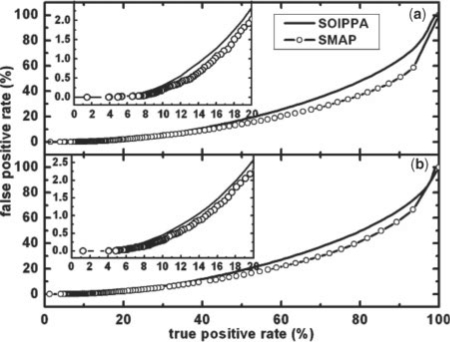

3.1.1 Performance of the EVD model

The new EVD model improves the database search speed of SOIPPA by at least two-order of magnitude when compared to the non-parametric method that requires hundreds of comparisons to derive a background distribution (Xie and Bourne, 2008; Xie et al., 2007). Using the EVD model, the majority of computation is spent in the MWCS optimum alignment step. As shown in Figure 3, the total computational time for each comparison is approximately linearly dependent on the number of residues in the structure, although the underlying MWCS algorithm itself is NP hard. Because we use the geometric potential to reduce the search space, the computational time also depends on the surface properties of the structure. A structure with a smooth surface will be much faster than a structure with a rough surface. It takes ∼60 s to compare two polypeptide chains each of 500 residues.

Fig. 3.

Computational time for 5000 randomly selected non-redundant chains searched against two structures with chain lengths of 564 (red triangle) and 166 (black diamond), respectively.

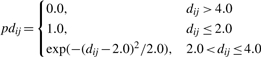

Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of the database search is not sacrificed but slightly improved when compared with the non-parametric statistical method (Xie and Bourne, 2008). As shown in Figure 4, the true positive rate increases around 2% and 1% for BLOSUM45 and McLachlan substitution matrix, respectively, when the false positive rate is 1%. The benchmark that is used for the evaluation is given in the method section. As shown previously (Xie and Bourne, 2008), a weighted scoring scheme as used by SOIPPA outperforms a non-weighted vertex matching method as used by most-existing algorithms. Thus, SOIPPA using the EVD statistical model represents progress toward establishing a robust, accurate and scalable ligand-binding-site-comparison methodology.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of false positive rate versus true positive rate for the original SOIPPA algorithm (Xie and Bourne, 2008) (solid) and the improved SMAP implementation (dashed with circles) using (a) BLOSUM45 and (b) McLachlan substitution matrices. The details of the benchmark used are given in the method section.

3.1.2 Application to drug discovery

Given the improved speed and accuracy of SOIPPA, the new statistical model permits us to search for ligand–binding-site similarity on a genome-wide scale. We have implemented both the SOIPPA and the EVD model into software called SMAP. Using SMAP, we have successfully identified off-targets for several pharmaceuticals either already on the market or in clinical trials. In one case we have revealed a complex off-target-binding network for cholesteryl ester transporter protein (CETP) inhibitors (Xie et al., 2009). The identified off-targets are involved in both positive and negative control of blood pressure, providing a molecular basis for the underlying clinical indications of CETP inhibitors.

Here, we further apply SMAP to an all-against-all ligand–binding-site comparison across the M. tuberculosis structural genome in an effort to construct a genome-scale protein–ligand interaction network. Our purpose is to discover protein clusters that have similar ligand–binding sites and hence are good drug target candidates to rationally design promiscuous drugs that are able to inhibit multiple targets. It is believed that multi-target therapy is more effective than single-target therapy to treat parasitic diseases such as drug-resistant tuberculosis (Kitano, 2007). In addition, such protein–ligand interaction networks may provide molecular insights into the mechanism of drug resistance (Raman and Chandra, 2008). In our initial study of 232 non-redundant M. tuberculosis proteins, SMAP generates a highly connected network with highly a confident P-value cut-off of 1.0e–7. As shown in Figure 5, 144 proteins form a large single linkage cluster. The top 18 mostly highly connected proteins are listed in Table 2. The list is dominated by dehydrogenases and reductases, including the most-studied M. tuberculosis drug target Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase (InhA). The drug isoniazid that targets InhA has been the most used first-line anti-tuberculosis therapy for decades. The gene Rv3303c that encodes the most connected dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (LPDA) in the network is found to be up-regulated during infection and growth in vivo (Deb et al., 2002). Besides dehydrogenases and reductases, other highly connected proteins such as inorganic polyphosphate/ATP–NAD kinase and serine protease PEPD play key roles in bacterial survival but to date orthologs have not been found in higher-order eukaryotes (Brown and Kornberg, 2008; Ribeiro-Guimarães and Pessolani, 2007). Recently, inhibitors of inorganic polyphosphate/ATP–NAD kinase have been developed (Bonnac et al., 2007). Thus, most of the proteins listed in Table 2 are potential novel drug targets for the development of efficient anti-tuberculosis chemotherapeutics.

Fig. 5.

Predicted protein–ligand interaction network of M. tuberculosis. Proteins that are predicted to have similar binding sites are connected. Squares represent the top 18 most connected proteins.

Table 2.

Top 18 mostly connected proteins (number of neighbors > 12) in the protein–ligand interaction network of M.tuberculosis

| PDB id | Protein name | Gene name | Links | SMAP P-valuea | Drug PDB idb | eHits Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1xdi | Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase LPDA | Rv3303c | 24 | 0.000 | NMG | −5.56 |

| 2ied | Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH] | Rv1484 | 20 | Drug target of isoniazid | ||

| 1u0r | Inorganic polyphosphate/ATP-NAD kinase | Rv1695 | 20 | 9.904E-6 | FNM | −4.59 |

| 1me5 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase ahpD | Rv2429 | 20 | 7.187E-4 | P1Z | −4.23 |

| 2i3g | N-acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase | Rv1652 | 17 | 1.810E-7 | 2ML | −3.98 |

| 1ted | Chalcone/stilbene synthase family protein | Rv1372 | 17 | 5.119E-6 | OHA | −5.12 |

| 3ddn | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | Rv2996c | 16 | 8.245E-6 | ROC | −8.00 |

| 3cy1 | Cytochrome P450 121 | Rv2276 | 16 | Drug metabolizing enzyme | ||

| 1y8t | Serine Protease PEPD | Rv0983 | 16 | 9.565E-4 | 505 | −3.96 |

| 2vp8 | Dihydropteroate Synthase 2 | Rv1207 | 15 | 9.458E-4 | E3O | −4.66 |

| 2q74 | Inositol-1-monophosphatase | Rv2701c | 15 | 8.944E-5 | ID2 | −2.57 |

| 2c7g | NADPH-ferredoxin reductase fprA | Rv3106 | 14 | 9.992E-16 | URF | −4.34 |

| 2c45 | Aspartate 1-Decarboxylase Precursor | Rv3601c | 14 | 1.259E-3 | RIS | −0.38 |

| 1nfr | 3-α-(or 20-β)-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Rv2002 | 14 | 1.000E-9 | TOY | −5.15 |

| 2qj3 | Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase | Rv2243 | 12 | 2.507E-5 | E3O | −4.38 |

| 2a87 | Thioredoxin reductase | Rv3913 | 12 | 4.957E-11 | RBF | −6.07 |

| 1yl7 | Dihydrodipicolinate reductase | Rv2773c | 12 | 3.918E-5 | BA3 | −3.78 |

| 1v92 | NSFL1 cofactor p47 | Rv2150c | 12 | >1.000E-2 | – | – |

aPresents the lowest P-value between the identified hub proteins and 305 proteins binding with existing drugs in PDB.

bPresents the drugs with the lowest eHiTs score when docked to the identified hub proteins.

To further assess the druggability of the enzymes that are listed in Table 2, but have not been actively pursued by the pharmaceutical industry, using SMAP we compared and superimposed them with complex structures that bind to existing drugs in PDB. The superimposition generates a predicted binding pose of the drug with the target. The surrounding residues of the drug can be considered as the predicted drug-binding site. Furthermore, we docked the drug molecules to the predicted drug-binding site using the software eHiTs (Zsoldos et al., 2007). The estimated binding affinity indicated whether or not the predicted binding site is favorable for drug binding. In addition, it provided valuable clues for repurposing safe pharmaceuticals to treat tuberculosis (Kinnings et al., 2009). As shown in Table 2, most of the predicted binding sites were similar to a known drug-binding site with high statistical significance (P-value < 1.0E–4). Moreover, the docking scores suggested that the drug-like molecule could fit into most binding sites.

4 DISCUSSION

Unlike similar sequences or structures, sequence order is not always conserved between two similar functional sites. This presents a problem in achieving the optimum alignment of two ligand-binding sites. Further, most current alignment algorithms only use a crude classification of amino-acid conservation rather than a quantitative measurement such as those presented in an amino-acid substitution matrix. Exceptions can be found (Binkowski et al., 2003; Laskowski et al., 2005; Pazos and Sternberg, 2004; Powers et al., 2006) but sequence order constraints are usually imposed. To address the issues of sequence order independence and evolutionary conservation, we encode amino-acid residues in the ligand-binding site as an undirected graph. Using the graph representation, two ligand-binding sites can be aligned by finding the MWCS. Although the maximum-size clique algorithm without weights has been widely used in chemo and bioinformatics, incorporation of the weights into the comparison makes fundamental differences. Analogous to conventional sequence alignment without weights, the similarity between two aligned sequences can only be measured with sequence identity. With weights such as a value from a substitution matrix incorporated into the sequence comparison, similarity scores can capture more evolutionary and physio-chemical information and give more statistically meaningful results. As demonstrated previously, the MWCS-based SOIPPA algorithm outperform the non-weighted method (Xie and Bourne, 2008). However, the SOIPPA algorithm imposes new challenges on the efficient assessment of statistical significance because the conventional probability model that is developed based on vertex matching cannot be applied. Previously, a background distribution has been derived from hundreds of random alignments. Then the P-value is estimated using a non-parametric statistical method. In this article, we have found that the weighted score from the MWCS alignment follows EVD nearly identical to global sequence and structure alignment. It allows us to develop an efficient unified statistical framework to compare two proteins at multiple scales. The EVD model eliminates the requirement for additional alignments that are used to generate the background distribution, and thus speeds up the computation for a pair-wise comparison of ligand-binding sites by at least 100-fold. As a result, it is possible for us to apply ligand-binding site similarity searching to complete genomes. It took less than 1 week to compute an all-against-all comparison of the M. tuberculosis structural genome on a PC with one 3.0 GHz CPU.

The algorithm presented in this article can be further improved in the future. The Mclachlan (McLachlan, 1972) and BLOSUM45 (Henikoff and Henikoff, 1992) amino-acid substitution matrixes used in this study are derived from whole proteins or domains and hence are not customized for the ligand-binding site. By using a scoring matrix that is specific to an individual binding site, the performance of inferring protein functions can be dramatically improved (Tseng et al., 2009; Tseng and Liang, 2006). It will be interesting to apply the EVD model developed here using a ligand-binding-site-specific scoring matrix. Moreover, it is a challenge to randomly sample ligand-binding site space by taking into account both protein surface geometry and amino-acid composition. The common practice is to use a non-redundant set of thousands of PDB structures to build a look-up table (Binkowski and Joachimiak, 2008). However, the structural coverage in PDB is highly biased (Xie and Bourne, 2005). This bias is especially true for ligand-binding sites. The PDB is dominated by ligands such as nucleotides and their analogs. More fundamental, growing evidence indicates that protein space could be continuous and related by ligand-binding sites (Andreeva and Murzin, 2006; Bashton and Chothia, 2007; Choi and Kim, 2006; Fong et al., 2007; Friedberg and Godzik, 2005; Grishin, 2001; Kolodny et al., 2006; Pan and Bardwell, 2006; Reeves et al., 2006; Shindyalov and Bourne, 2000; Taylor, 2007; Winstanley et al., 2005; Xie and Bourne, 2008). Thus, it may not be appropriate to derive the background distribution directly from existing structures as they are not structurally, functionally and evolutionarily random. Keeping this in mind, we selected a set of structures from different CATH classes and built random models seeded from them. These models are the least likely to be directly related. However, one may argue that the number of models that are used to generate the background distribution is still small. Although the sequence space can be sufficiently sampled by varying the sequence composition and order, the random geometric sampling is limited by total number of residues in the 36 structures, which is in the order of 107. To improve the random sampling of the protein surface, decoy structures could be used as in structural comparison (Taylor, 2006). We are in the process of developing the random decoy structure model and deriving a more robust and reliable statistical model for the ligand-binding site search. Finally, the geometric statistical model may also be affected by how we represent the protein structure. Because we only use a Cα representation in SOIPPA for the purpose of applying it to homology models, it is not clear if the EVD estimation is applicable to the ligand-binding site comparison when using an all-atom presentation.

Our initial study of the M. tuberculosis protein–ligand interaction network indicates that it is possible to design promiscuous drugs that are able to inhibit multiple proteins within the organism because a number of proteins share the similar ligand-binding sites with each other. The predicted binding network may also establish new opportunities to combat drug resistance. There are three types of known drug resistance mechanisms: (i) mutations in the drug targets and the regulatory genes through SOS response such as cytochrome P450 (Johnson et al., 2006), (ii) activation of efflux pumps and drug modifying enzymes (Nguyen and Thompson, 2006) and (iii) acquisition of drug detoxification genes through horizontal gene transfer (Smith and Romesberg, 2007). Recently, Raman et al. have constructed and analyzed a TB protein–protein interaction network and identified several resistance pathways involving the above mechanisms (Raman and Chandra, 2008). There is no doubt that a detailed ligand-binding site analysis between the drug target and the genes that are responsible for drug resistance will provide invaluable clues in designing drugs that inhibit not only essential genes but also co-targets that are not necessarily essential for the bacteria to survive but mediate drug resistance. Even in our initial small-scale study, we identify one of such protein, cytochrome P450 121 that has shown significant binding-site promiscuity with a number of potential drug targets (rank 8 in Table 2). To develop antibacterial therapies that are less liable to drug resistance, the inhibitor should be designed to retain binding to the primary targets but reduce binding to co-targets such as cytochrome P450. Another strategy is to develop combined therapeutics that inhibits the target and the co-target simultaneously. More studies are required to validate our findings. We need to understand how proteins are involved in metabolic, gene regulation and signal transduction pathways; what roles they play in drug resistance and whether or not they have cross-reactivity with human proteins. A chemical systems biology approach, which integrates the protein–ligand interaction network outlined in the article along with the reconstruction and the simulation of the biological pathways, will play a critical future role in addressing these issues. Our own efforts in this direction are on going.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions in improving the manuscript.

Funding: National Institutes of Health grant GM078596.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- AltschulS F, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva A, Murzin AG. Evolution of protein fold in the presence of functional constraints. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artymiuk PJ, et al. A graph-theoretic approach to the identification of three-dimensional patterns of amino acid side-chains in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;243:327–344. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JA, Thornton JM. An algorithm for constraint-based structural template matching: application to 3D templates with statistical analysis. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1644–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashton M, Chothia C. The generation of new protein functions by the combination of domains. Structure. 2007;15:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski TA, et al. Inferring functional relationships of proteins from local sequence and spatial surface patterns. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;332:505–526. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00882-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski TA, Joachimiak A. Protein functional surfaces: global shape matching and local spatial alignments of ligand binding sites. BMC Struct. Biol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnac L, et al. Probing binding requirements of NAD kinase with modified substrate (NAD) analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:1512–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakoulias A, Jackson RM. Towards a structural classification of phosphate binding sites in protein-nucleotide complexes: an automated all-against-all structural comparison using geometric matching. Proteins. 2004;56:250–260. doi: 10.1002/prot.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MRW, Kornberg A. The long and short of it - polyphosphate, PPK and bacterial survival. Trends in Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammer SA, et al. Structure-based active site profiles for genome analysis and functional family subclassification. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SJ, et al. Ligand binding: functional site location, similarity and docking. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BY, et al. Algorithms for structural comparison and statistical analysis of 3D protein motifs. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2005;10:334–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi I-G, Kim S-H. Evolution of protein structural classes and protein sequence families. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14056–14061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606239103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie JM. Some useful statistical properties of position-weight matrices. Comput. Chem. 1994;18:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0097-8485(94)85024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JR, et al. The Poisson Index: a new probabilistic model for protein ligand binding site similarity. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3001–3008. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb DK, et al. Selective identification of new therapeutic targets of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by IVIAT approach. Tuberculosis. 2002;82:175–182. doi: 10.1054/tube.2002.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande N, et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: a redesigned query system and relational database based on the mmCIF schema. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D233–D237. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson PD, et al. Prediction of protein function in the absence of significant sequence similarity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:2135–2142. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong JH, et al. Modeling the evolution of protein domain architectures using maximum parsimony. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;366:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg I, Godzik A. Connecting the protein structure universe by using sparse recurring fragments. Structure. 2005;13:1213–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC. Divergent evolution of enzymatic function: mechanistically diverse superfamilies and functionally distinct suprafamilies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:209–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherardini PF, et al. Convergent evolution of enzyme active sites is not a rare phenomenon. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:817–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PJ. Bayesian alignment using hierarchical models, with applications in protein bioinformatics. Biometrika. 2006;93:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Grishin NV. Fold change in evolution of protein structures. J. Struct. Biol. 2001;134:167–185. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther S, et al. SuperTarget and Matador: resources for exploring drug-target relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D919–D922. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S, Henikoff JG. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanisenko VA, et al. PDBSiteScan: a program for searching for active, binding and posttranslational modification sites in the 3D structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W549–W554. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambon M, et al. A new bioinformatic approach to detect common 3D sites in protein structures. Proteins. 2003;52:137–145. doi: 10.1002/prot.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, et al. Drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2006;8:97–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnings S, et al. Drug discovery using chemical systems biology: discovery of novel drug leads to treat multi-drug and extensively drug resistant tuberculosis by repositioning safe pharmaceuticals. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000423. manuscript submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, et al. Identification of protein functions from a molecular surface database, eF-site. J. Struc. Func. Genomics. 2001;2:9–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1011318527094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, Nakamura H. Identification of protein biochemical functions by similarity search using the molecular surface database eF-site. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1589–1595. doi: 10.1110/ps.0368703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H. A robustness-based approach to systems-oriented drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:202–210. doi: 10.1038/nrd2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ. Recognition of spatial motifs in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1887–1897. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodny R, et al. Protein structure comparison: implications for the nature of ‘fold space’, and structure and function prediction. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D, et al. From the similarity analysis of protein cavities to the functional classification of protein families using cavbase. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:1023–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumlander D. A new exact algorithm for the maximum-weight clique problem based on a heuristic vertex-coloring and a backtrack search. 4th European Congress of Mathematics. 2004;127:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, et al. Protein function prediction using local 3D templates. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:614–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M, Gerstein M. A unified statistical framework for sequence comparison and structure comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5913–5920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardia KV, et al. Bayesian refinement of protein functional site matching. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:257. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan AD. Repeating sequences and gene duplication in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;64:417–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng EC, et al. Superfamily active site templates. Proteins. 2004;55:962–976. doi: 10.1002/prot.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, et al. Real Spherical harmonic expansion coefficients as 3D shape descriptors for protein binding pocket and ligand comparisons. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2347–2355. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L, Thompson CJ. Foundations of antibiotic resistance in bacterial physiology: the mycobacterial paradigm. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostergard PRJ. A new algorithm for the maximum-weight clique problem. Nordic J. Comput. 2001;8:424–436. [Google Scholar]

- Ostergard PRJ. A fast algorithm for the maximum clique problem. Discrete Appl. Math. 2002;120:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pan JL, Bardwell JCA. The origami of thioredoxin-like folds. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2217–2227. doi: 10.1110/ps.062268106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazos F, Sternberg MJE. Automated prediction of protein function and detection of functional sites from structure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14754–14759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404569101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WR. Empirical statistical estimates for sequence similarity searches. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:71–84. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering SJ, et al. AI-based algorithms for protein surface comparison. Comput. Chem. 2001;26:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0097-8485(01)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers R, et al. Comparsion of protein active site structures for functional annotation of proteins and drug design. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2006;65:124–135. doi: 10.1002/prot.21092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman K, Chandra N. Mycobacterium tuberculosis interactome analysis unravels potential pathways to drug resistance. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves GA, et al. Structural diversity of domain superfamilies in the CATH database. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;360:725–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Guimarães ML, Pessolani MC. Comparative genomics of mycobacterial proteases. Microb. Pathog. 2007;43:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RB. Detection of protein three-dimensional side-chain patterns: new examples of convergent evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:1211–1227. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeff ED, Bourne PE. Structural evolution of the protein kinase-like supefamily. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2005;1:e49. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt S, et al. A new method to detect related function among proteins independent of sequence and fold homology. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;323:387–406. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. An alternative view of protein fold space. Proteins. 2000;38:247–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman-Peleg A, et al. Recognition of functional sites in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;339:607–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggers TW, et al. Structural alignment of protein–DNA interfaces: insights into the determinants of binding specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:1027–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PA, Romesberg FE. Combating bacteria and drug resistance by inhibiting mechanisms of persistence and adaptation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:549–556. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Waterman MS. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Russell RB. Annotation in three dimensions. PINTS: patterns in non-homologous tertiary structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3341–3344. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, et al. A model for statistical significance of local similarities in structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. Decoy models for protein structure score normalisation. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:676–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. Evolutionary transitions in protein fold space. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance JW, et al. Using a library of structural templates to recognise catalytic sites and explore their evolution in homologous families. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;347:565–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YY, et al. Predicting protein function and binding profile via matching of local evolutionary and geometric surface patterns. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;387:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YY, Liang J. Estimation of amino acid residue substitution rates at local spatial regions and application in protein function inference: a Bayesian Monte Carlo approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:421–436. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AC, et al. TESS: a geometric hashing algorithm for deriving 3D coordinate templates for searching structural databases. Application to enzyme active sites. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2308–2323. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, et al. Unexpected nanomolar inhibition of carbonic anhydrase by COX-2-selective celecoxib: new pharmacological opportunities due to related binding site recognition. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:550–557. doi: 10.1021/jm030912m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley HF, et al. How old is your fold? Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl. 1):i449–i485. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Bourne PE. Functional coverage of the human genome by existing structures, structural genomics targets, and homology models. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2005;1:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Bourne PE. Detecting evolutionary relationships across existing fold space, using sequence order-independent profile–profile alignments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5441–5446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704422105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, et al. Drug discovery using chemical systems biology: identification of the protein-ligand binding network to explain the side effects of CETP inhibitors. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000387. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, et al. In silico elucidation of the molecular mechanism defining the adverse effect of selective estrogen receptor modulators. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2007;3:e217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Grigorov MG. Similarity networks of protein binding sites. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2006;62:470–478. doi: 10.1002/prot.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsoldos Z, et al. eHiTS: A new fast, exhaustive flexible ligand docking system. J. Mol. Graph Model. 2007;26:198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]