Abstract

Motivation: The IUBMB's Enzyme Nomenclature system, commonly known as the Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, plays key roles in classifying enzymatic reactions and in linking the enzyme genes or proteins to reactions in metabolic pathways. There are numerous reactions known to be present in various pathways but without any official EC numbers, most of which have no hope to be given ones because of the lack of the published articles on enzyme assays.

Results: In this article we propose a new method to predict the potential EC numbers to given reactant pairs (substrates and products) or uncharacterized reactions, and a web-server named E-zyme as an application. This technology is based on our original biochemical transformation pattern which we call an ‘RDM pattern’, and consists of three steps: (i) graph alignment of a query reactant pair (substrates and products) for computing the query RDM pattern, (ii) multi-layered partial template matching by comparing the query RDM pattern with template patterns related with known EC numbers and (iii) weighted major voting scheme for selecting appropriate EC numbers. As the result, cross-validation experiments show that the proposed method achieves both high coverage and high prediction accuracy at a practical level, and consistently outperforms the previous method.

Availability: The E-zyme system is available at http://www.genome.jp/tools/e-zyme/

Contact: kanehisa@kuicr.kyoto-u.ac.jp

1 INTRODUCTION

Metabolic network is one of the important classes of biological networks, consisting of enzymatic reactions involving substrates and products. Recent developments in pathway databases, such as KEGG PATHWAY (Kanehisa et al., 2008), enable us to analyze the known metabolic networks. However, most organism-specific metabolic networks are left with a number of unidentified enzymatic reactions, that is, many enzymes are missing in the known metabolic pathways. Since experimental determination of such missing enzymes and their relevant pathways is very difficult and too expensive, in silico prediction of such enzymatic reactions in the metabolic network is a challenging area in computational biology.

In recent years, the importance of chemical genomics research is growing fast (Dobson, 2004; Kanehisa et al., 2006; Stockwell, 2000). The high-throughput screening of chemical compound libraries with various biological assays is beginning to produce huge amounts of chemical data. We are now confronted with the necessity to automate the processing and interpretation of such chemical data in order to derive biologically meaningful information. In particular, the prediction of unknown reactions is an important issue for interpretation of metabolomic and other experimental data aimed toward drug discovery and the evaluation of an organism's response to environmental changes (Nobeli and Thornton, 2006). There is therefore a strong incentive to develop computational systems for predicting the potential chemical reactions from given chemical structures, taking into account prior knowledge about the known enzymatic reactions.

The Enzyme Commission (EC) number plays a key role in the computational representation of enzymatic reactions in the metabolic network. Basically, the EC numbers represent a hierarchical classification of enzymatic reactions, where the first three digits of each EC number represent the chemical reaction type with which an enzyme is involved, and the fourth digit represents the substrate specificity or serial number (Barrett et al., 1992; Tipton and Boyce, 2000). In many public bio-databases, the EC numbers are also commonly utilized as identifiers of enzymes in the metabolic pathway maps, which enable us to link the enzymes to the chemical reactions in metabolic pathways (Kanehisa et al., 2008). Traditionally, each enzyme has been identified by detecting its activity in an individual experiment, which are to be reported to and registered in the Enzyme Nomenclature system (Barret et al., 1992; Tipton and Boyce, 2000). However, numerous reactions are known to be present in various pathways yet are unlikely to get EC numbers because of the principle that only enzymes with the confirmed existence of catalytic activity should be given EC numbers. Recently, the classification of enzymatic reactions has been conducted on a genome-scale and a computational method for assigning EC numbers has been proposed based on exact template matching and simple major voting (Kotera et al., 2004), although the coverage and the prediction accuracy are not at a practical level.

In this article we propose a new method to predict an EC sub-subclass based on our original biochemical transformation pattern which we call an ‘RDM pattern’, and develop a web-server called ‘E-zyme’ which enables us to automatically assign the potential EC numbers to given reactant pairs (substrates and products) or uncharacterized reactions. The new algorithm consists of three steps as follows: (i) graph alignment of a query reactant pair for computing the query RDM pattern, (ii) multi-layered partial template matching by comparing the query RDM pattern with the template RDM patterns related with known EC numbers and (iii) weighted major voting scheme for selecting appropriate EC numbers. Of these three steps, the second one should work for the improvement of the coverage and the third one to improve the prediction accuracy. Since it is impossible to predict the fourth digit of an EC number because it usually reflects on many other factors rather than only the reaction patterns, we focus on the prediction of the first three digits of the EC number (EC sub-subclass) in this study. The cross-validation experiments showed that the proposed method achieved both high coverage and high prediction accuracy and that it consistently outperformed the previous method (Kotera et al., 2004). The web-based application program ‘E-zyme’ is available as the rapid and high performance tool for chemical annotation at http://www.genome.jp/tools/e-zyme/.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 RDM pattern

Discriminating biochemical structure transformation patterns is an initial step toward reaction prediction. Most previously proposed definitions are based on the recognition of functional groups and their transformation patterns in organic compounds, and the transformation roles have been manually extracted in a knowledge-based context (Darvas, 1988; Ellis et al., 2006; Hou et al., 2004; Klopman and Tu, 1997; Langowski and Long, 2002; Mayeno et al., 2005; McShan et al., 2004; Talafous et al., 1994).

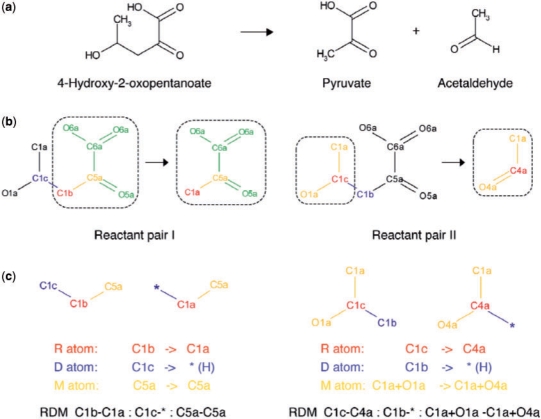

To represent biochemical structure transformation roles for reactant pairs in a systematic way, we developed a reaction classification approach which we call ‘reactant pairs’ and ‘RDM patterns’ in our previous work (Kotera et al., 2004). We defined a reactant pair as a pair of one substrate and one product of a given enzyme reaction equation, where at least one atom other than hydrogen atoms is preserved. The RDM pattern represents KEGG atom type changes at the reaction center atom (R atom) and its neighboring atoms on the different (mismatched) region (D atom) and the matched region (M atom) based on a chemical structure alignment algorithm (Hattori et al., 2003). For notation simplicity, we describe the R, D and M atoms as ‘R’, ‘D’ and ‘M’, respectively. Figure 1 shows an example of RDM patterns.

Fig. 1.

The alignment of reactant pairs and the definition of RDMs in an enzyme-catalyzed reaction (R00750 in KEGG). (a) The overall reaction where 4-hydroxy-2-oxopentanoate (C03589) is catalyzed to pyruvate (C00022) and acetaldehyde (C00084) by lyases (aldehyde-lyases or oxo-acid-lyases: EC 4.1.2.- or 4.1.3.-). (b) The reaction is decomposed into a couple of reactant pairs: reactant pair I (RP01083) containing pyruvate and reactant pair II (RP01084) containing acetaldehyde. The matched substructures obtained by SIMCOMP alignments are shown by dotted boxes for both pairs. Each structure is labeled with the KEGG atom types in order to reflect the environmental features of each atom, such as adjacent atoms, single, double, triples and aromatic bonds. The RDM atoms are colored in red, blue and yellow, respectively. The matched structure except the R and M atoms is colored in green. (c) The RDM patterns extracted from the two reactant pairs, where asterisks indicate hydrogen atoms. The RDM pattern is a set of KEGG atom type changes, such as C1b-C1a in the R atom, C1c-* in the D atoms and C5a-C5a in the M atoms for the reactant pair I.

The RDM patterns have been computed for all reactant pairs stored in the KEGG LIGAND database, and all the results have been stored in the RPAIR database for further analyses (Oh et al., 2007). Thus, the RPAIR database is a library of RDM patterns and structural alignments, representing our current knowledge on the universe of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The whole kinetic processes of enzymatic reactions contain a great deal of variation and some of them are very difficult to understand at a glance. However, using this library we can describe any enzymatic reactions by the unified notation around the reaction centers and can compare them each other.

Table 1 summarizes the data statistics of the RDM patterns in the RPAIR database at the time of writing, where the utilized R, D and M atoms are connected with colons (e.g. ‘R:D’ discriminates R and D atoms but not M atoms). In other words, Table 1 represents the number of reported reaction types with different resolutions. A reaction may consist of multiple reactant pairs derived from multiple substrates and products. From the standpoint of trying to find enzymes with known substrates and products, there should be the search option where one can input as much information as is available. Therefore, we defined two different options of the RDM patterns: the single mode and the multiple mode. The single mode deals with one reactant pair as a query, so the corresponding RDM pattern means a combination of R, D and M atoms of the reactant pair. To date, there are 5327 unique reactant pairs derived from 5669 known enzymatic reactions, and the number of the corresponding RDM patterns of ‘R:D:M’ type is 1877, for example. On the other hand, the multiple mode deals with multiple reactant pairs corresponding to one whole reaction, so the corresponding RDM pattern means a combination of R, D and M atoms taken from multiple reactant pairs. Out of the 5669 known enzymatic reactions, there are 2301 unique RDM patterns of ‘R:D:M’ type, for example. In a practical use, as mentioned in Discussion section, users can input any compound structures of interest, regardless of whether or not the compounds have been registered in the KEGG database.

Table 1.

Statistics of the RDM patterns in the RPAIR database (as of June 2008)

| Statistics | Single mode | Multiple mode |

|---|---|---|

| Number of reactant pairs | 5327 | - |

| Number of reactions | - | 5669 |

| Number of unique ‘R:D:M’ types | 1877 | 2301 |

| Number of unique ‘R:D’ types | 1103 | 1443 |

| Number of unique ‘R:M’ types | 1376 | 2071 |

| Number of unique ‘D:M’ types | 1805 | 2272 |

| Number of unique ‘R’ atom types | 607 | 1078 |

| Number of unique ‘D’ atom types | 727 | 1031 |

| Number of unique ‘M’ atom types | 1131 | 1836 |

A total of 5327 reactant pairs were assigned from 5669 reactions involving 4302 compounds. The numbers of unique RDM patterns are shown here for all possible combinations of the different atom types: ‘R’, ‘D’ and ‘M’.

2.2 Pre-calculated association of RDM patterns and EC numbers

Prior to the prediction procedures, we prepared a set of template RDM patterns as {RDMi} i=1|RDM|, where |RDM| is the number of unique template RDM patterns, and a set of EC sub-subclasses (the first three digits of EC numbers) as { ECk } k=1|EC|, where |EC| is the number of unique EC sub-subclasses. Note that we only used template RDM patterns assigned to at least one EC number.

To represent the association between the RDM pattern and the EC sub-subclass, we define a reaction pattern profile for each RDM pattern, which is defined as x=(x1,x2,…,x|EC|)T, where the k-th element is the number of reported reactions for the k-th EC sub-subclass. Then, we represent all the template RDM patterns by the reaction pattern profile as {xi}i=1|RDM|.

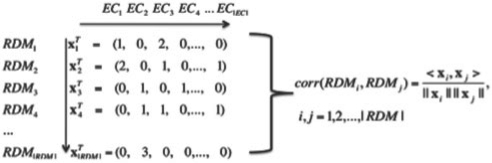

To evaluate the similarity between two template RDM patterns, we propose to compute the correlation coefficient between the corresponding reaction pattern profiles xi and xj using the cosine correlation coefficient defined as

where, ‖·‖ is the Euclidian norm and <·,·> is the inner product. Figure 2 shows an illustration of reaction pattern profile and reaction similarity.

Fig. 2.

An illustration of the reaction pattern profile for each RDM pattern and the computation of the reaction similarity.

We apply this operation to each RDM type and construct the reaction similarity matrices for seven RDM types: ‘R:D:M’, ‘R:D’, ‘D:M’, ‘R:M’, ‘R’, ‘D’ and ‘M’, respectively.

2.3 Prediction procedure

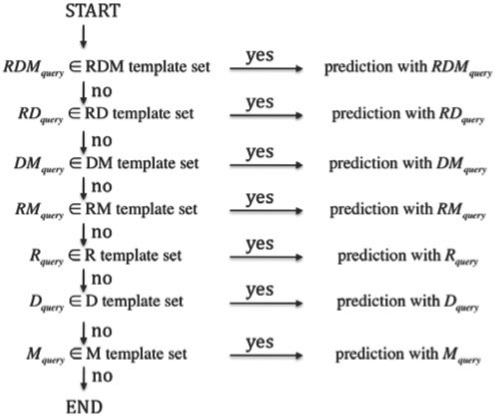

Consider the situation where, given a query reactant pair, we want to predict the EC sub-subclass for the reactant pair. Searching only the same template pattern with the query RDM pattern, just as the previous method (Kotera et al., 2004), often makes the users meet the case where the users cannot receive any response from the prediction engine in practical applications. To improve the coverage as well as the precision, we propose a multi-layered reaction pattern profile scheme. The prediction proceeds according to the following steps. First, the chemical structure alignment outputs the RDM pattern(s) of the query reactant pairs. Consequently, the multi-layered reaction pattern profiles work as sieves: the query that does not match any reaction patterns in the upper layer is passed to the lower layer with looser matching conditions (Fig. 3). In each layer a reaction pattern profile is defined to select similar reaction patterns with the query.

Fig. 3.

An illustration of the sequentially conducted partial matching procedure. In the process of prediction with each RDM type, the reaction similarity for each RDM type is evaluated in the weighted major voting.

First, the RDM pattern for a query reactant pair is computed based on the chemical structure alignment, which is described as RDMquery below. The EC number prediction starts with the search for EC sub-subclasses associated with the template RDM pattern matched with RDMquery. Consequently, in order to select the most appropriate EC sub-subclass out of the candidate EC set {ECk}k=1|EC|, the candidate score is computed for each candidate EC sub-subclass as follows:

where, xi,k is the frequency of ECk for RDMi, wquery, i is a weight function defined as wquery, i=1/(1 −exp(−d(cquery, i − h))), cquery, i=corr(RDMquery,RDMi), and the parameters are set as d=20 and h=0.7. The aim of using the sigmoid function in the weight wquery, i is to reduce the noise effect of lowly correlated EC sub-subclasses and to put emphasis on highly correlated EC sub-subclasses. After the candidate scores are calculated for all EC sub-subclasses in the database, the EC sub-subclass with the highest score is regarded as predicted, in the spirit of a majority vote.

Each of the seven layers performs a similarity search of the RDM patterns in the same manner as ‘R:D:M illustrated in Figure 2, with the pre-calculated similarity matrices for seven RDM types (‘R:D:M’, ‘R:D’, ‘D:M’, ‘R:M’, ‘R’, ‘D’ and ‘M’, respectively). The order of the different layers in the partial matching described in Figure 3 is determined based on the contributions of each RDM type for the reaction prediction (for details, see the Result section). This process is successively continued until no hits can be returned.

3 RESULTS

We performed a Jack-knife type (leave-one-out) cross-validation to evaluate the proposed method on its ability to predict the EC sub-subclass with two different modes: the single mode and the multiple mode. The procedure for the single mode is as follows:

Take one reactant pair from a set of template reactant pairs as a test query, and compute the RDM pattern.

Predict the EC number of the test query, based on the RDM patterns of the remaining template reactant pairs.

Evaluate the prediction result as follows: if the predicted EC with the highest candidate score is the real EC, it is regarded as a true positive, otherwise a false positive.

Repeat the above steps for all the template reactant pairs.

Note that the cross-validation for the multiple mode can be performed by replacing the reactant pair by the reaction in the above procedure, and the template reaction pattern profile used for computing the candidate score is constructed by removing the real EC number information for the test query in each cross-validation.

To examine the prediction ability of each layer, we evaluated the performance of each RDM type in the EC number prediction individually, where the prediction is performed for the main class (the first digit of an EC number) and the subclass (the first two digits of an EC number) as well as the sub-subclass (the first three digits of an EC number), as shown in Table 2. In each case, the performance was evaluated by using several statistics: coverage, recall (sensitivity), and precision (positive predictive value). The coverage is defined as the proportion of possible predictions against all queries. The recall is defined as TP/(TP+FN) and the precision is defined as TP/(TP+FP), where TP, FP and FN are the number of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The contribution of each RDM type for the reaction prediction depends on how detailed the chemical transformation pattern is discriminated, namely, the number of atoms comprising the RDM type. This indicates that the most informative combination of R-atom, D-atom and M-atom is the triplet (‘R:D:M’), followed by the pairs (‘R:D’, ‘D:M’ and ‘R:M’), and the singlet (‘R’, ‘D’ and ‘M’) in terms of precision.

Table 2.

The prediction performance for each individual prediction layer

| Layer | Statistics | Single mode |

Multiple mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC main | EC sub | EC subsub | EC main | EC sub | EC subsub | ||

| R:D:M | Coverage | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.754 | 0.754 | 0.754 |

| Recall | 0.629 | 0.608 | 0.546 | 0.679 | 0.658 | 0.619 | |

| Precision | 0.817 | 0.790 | 0.710 | 0.901 | 0.873 | 0.821 | |

| R:D | Coverage | 0.878 | 0.878 | 0.878 | 0.849 | 0.849 | 0.849 |

| Recall | 0.718 | 0.680 | 0.594 | 0.788 | 0.751 | 0.698 | |

| Precision | 0.817 | 0.775 | 0.677 | 0.928 | 0.884 | 0.822 | |

| D:M | Coverage | 0.773 | 0.773 | 0.773 | 0.730 | 0.730 | 0.730 |

| Recall | 0.629 | 0.607 | 0.538 | 0.681 | 0.659 | 0.618 | |

| Precision | 0.813 | 0.785 | 0.696 | 0.932 | 0.902 | 0.847 | |

| R:M | Coverage | 0.836 | 0.836 | 0.836 | 0.763 | 0.763 | 0.763 |

| Recall | 0.619 | 0.547 | 0.472 | 0.695 | 0.652 | 0.612 | |

| Precision | 0.741 | 0.655 | 0.565 | 0.911 | 0.855 | 0.802 | |

| R | Coverage | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.895 | 0.895 |

| Recall | 0.662 | 0.544 | 0.430 | 0.785 | 0.715 | 0.654 | |

| Precision | 0.706 | 0.581 | 0.458 | 0.877 | 0.799 | 0.731 | |

| D | Coverage | 0.919 | 0.919 | 0.919 | 0.894 | 0.894 | 0.894 |

| Recall | 0.710 | 0.646 | 0.538 | 0.803 | 0.738 | 0.658 | |

| Precision | 0.772 | 0.702 | 0.585 | 0.898 | 0.825 | 0.736 | |

| M | Coverage | 0.862 | 0.862 | 0.862 | 0.789 | 0.789 | 0.789 |

| Recall | 0.581 | 0.437 | 0.378 | 0.681 | 0.596 | 0.561 | |

| Precision | 0.674 | 0.506 | 0.438 | 0.863 | 0.755 | 0.711 | |

We compared the EC number prediction performance between the proposed method (weighted major voting scheme with multi-layered partial template matching) and the previous method (simple major voting scheme with exact template matching) (Kotera et al., 2004), as shown in Table 3. The proposed method outperforms the previous method in terms of high coverage, high recall and high precision in any EC classification level. High coverage demonstrates the usefulness of the partial matching of the RDM pattern and guarantees the robustness of the E-zyme system in actual applications. High recall and high precision is a positive effect of incorporating the correlation between the EC number and the RDM pattern in the weighed major voting process. These results indicate that the E-zyme system should work well for chemical reaction annotation at a practical level. In contrast, the template matching condition of the multiple mode is stricter than that of the single mode, which naturally leads to the idea that the former might have higher prediction accuracy with lower coverage.

Table 3.

Comparison of the prediction performance between the previous method (exact matching & simple major voting) and the proposed method (multi-layered matching & weighted major voting).

| Method | Statistics | Single mode |

Multiple mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC main | EC sub | EC subsub | EC main | EC sub | EC subsub | ||

| Previous | Coverage | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.754 | 0.754 | 0.754 |

| method | Recall | 0.629 | 0.608 | 0.546 | 0.679 | 0.658 | 0.619 |

| Precision | 0.817 | 0.790 | 0.710 | 0.901 | 0.873 | 0.821 | |

| Proposed | Coverage | 0.961 | 0.961 | 0.961 | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.933 |

| method | Recall | 0.803 | 0.765 | 0.683 | 0.875 | 0.839 | 0.794 |

| Precision | 0.835 | 0.796 | 0.711 | 0.937 | 0.899 | 0.851 | |

We also examined the effect of each of the layers by counting how many query compound pairs have been predicted as the real EC sub-subclasses in each layer along the cross-validation test. Unlike the independent result of each layer in Table 2, Table 4 shows the result when the prediction is performed hierarchically from ‘R:D:M’ to ‘M’ as illustrated in Figure 3. Among all possible permutations, the sequence R:D:M -> R:D -> D:M -> R:M -> R -> D -> M turned out to be the best in terms of the precision value. It is natural that the most informative layer (R:D:M) came to the top. In most cases, the prediction results can be obtained in the first or second layers. Using only the first layer (R:D:M), the coverage comes to 80.0% and 80.8% in the single and multiple modes, respectively. Adding the second layer (R:D) improves the coverage 92.3% and 93.4%, respectively. Depending on the EC classes, there are sometimes cases where the order of layers should be changed for better precision, reflecting the fact that the classification criteria differ in different classes. It might be worth trying some optimization method such as decision trees, to change the order of layers depending on the query RDM patterns.

Table 4.

The detailed performance for each layer in the prediction flow of the sequentially conducted partial matching procedure

| Total | EC1 | EC2 | EC3 | EC4 | EC5 | EC6 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidoreductases | Transferases | Hydrolases | Lyases | Isomerases | Ligases | |||||||||

| Layers | pairs | precision | pairs | precision | Pairs | precision | pairs | precision | pairs | precision | pairs | precision | pairs | Precision |

| Single mode | ||||||||||||||

| R:D:M | 4097 | 73.8% | 1318 | 79.5% | 1340 | 78.6% | 825 | 52.4% | 316 | 86.7% | 107 | 97.1% | 191 | 57.5% |

| R:D | 629 | 71.0% | 283 | 67.1% | 84 | 73.8% | 87 | 74.7% | 111 | 84.6% | 55 | 60.0% | 9 | 33.3% |

| D:M | 14 | 42.8% | 3 | 0.0% | 5 | 60.0% | 2 | 50.0% | 4 | 50.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| R:M | 187 | 47.0% | 52 | 40.3% | 57 | 45.6% | 34 | 55.8% | 38 | 50.0% | 2 | 50.0% | 4 | 50.0% |

| R | 117 | 43.5% | 45 | 60.0% | 16 | 56.2% | 12 | 41.6% | 33 | 24.2% | 9 | 22.2% | 2 | 0.0% |

| D | 57 | 42.1% | 27 | 29.6% | 5 | 60.0% | 4 | 50.0% | 10 | 80.0% | 9 | 22.2% | 2 | 50.0% |

| M | 19 | 10.5% | 8 | 12.5% | 7 | 14.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.0% |

| (No hit) | 207 | 0.0% | 61 | 0.0% | 38 | 0.0% | 32 | 0.0% | 50 | 0.0% | 23 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.0% |

| Total | 5327 | 71.1% | 1736 | 74.6% | 1514 | 76.4% | 964 | 54.4% | 515 | 78.6% | 182 | 78.0% | 209 | 55.5% |

| Multiple mode | ||||||||||||||

| R:D:M | 4274 | 87.6% | 1712 | 88.5% | 1415 | 88.9% | 648 | 81.0% | 227 | 95.5% | 107 | 97.1% | 165 | 75.7% |

| R:D | 670 | 84.1% | 287 | 83.2% | 97 | 90.7% | 104 | 89.4% | 113 | 92.0% | 59 | 59.3% | 10 | 50.0% |

| D:M | 8 | 62.5% | 1 | 100.0% | 3 | 66.6% | 4 | 50.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| R:M | 96 | 78.1% | 31 | 83.8% | 28 | 75.0% | 19 | 84.2% | 16 | 68.7% | 2 | 50.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| R | 123 | 56.0% | 45 | 66.6% | 26 | 50.0% | 18 | 61.1% | 27 | 37.0% | 6 | 66.6% | 1 | 100.0% |

| D | 100 | 37.0% | 45 | 22.2% | 28 | 60.7% | 3 | 66.6% | 14 | 50.0% | 8 | 0.0% | 2 | 50.0% |

| M | 20 | 45.0% | 5 | 80.0% | 7 | 42.8% | 2 | 50.0% | 5 | 20.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.0% |

| (No hit) | 378 | 0.0% | 143 | 0.0% | 76 | 0.0% | 44 | 0.0% | 81 | 0.0% | 23 | 0.0% | 11 | 0.0% |

| Total | 5669 | 85.1% | 2126 | 85.8% | 1604 | 87.4% | 798 | 81.4% | 402 | 87.0% | 182 | 79.1% | 179 | 73.7% |

4 IMPLEMENTATION

The new E-zyme system we have developed is a rapid and high performance tool for chemical annotation, and available at http://www.genome.jp/tools/e-zyme/. Operation of the E-zyme system is described below.

4.1 Input

The user can input compound names or identifiers (C number or D number) in the KEGG databases for substrates and products in the reactant pair of interest. It is also possible to import MOL files for the corresponding substrates and products, or put the MOL file text into the form. Then, the user can select the multiple mode when more than one reactant pairs can be defined, and otherwise select the single mode. Clicking the ‘View structures’ button in the input page takes the user to confirm the two-dimensional graph structures of the input compounds. Then, clicking the ‘Compute’ button proceeds the prediction process.

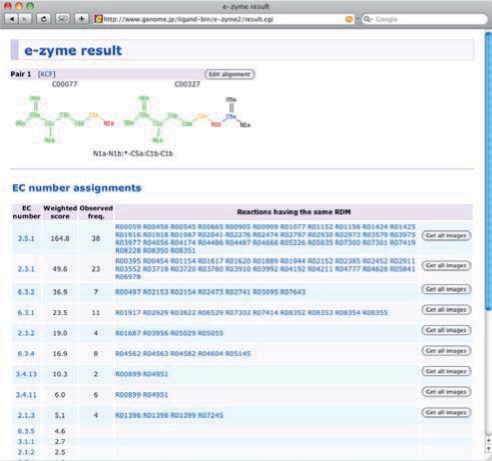

4.2 Output

The E-zyme system outputs the results of the alignment of the two compound structures and the predicted EC numbers. Figure 4 shows an example of the output page. In the page, each compound structure is labeled with the KEGG atom types, and the R-atom, D-atom, and M-atom in the RDM pattern are colored in red, blue and yellow, respectively, and the matched structure except the R and M-atoms is colored in green. In this case, the resulting RDM pattern is ‘N1a-N1b:*-C5a:C1b-C1b’, where ‘N1a-N1b’, ‘*-C5a’ and ‘C1b-C1b’ correspond to the R-atoms, D-atoms, and M-atoms, respectively. The weighted scores in the bottom of the page are the candidate scores defined in the Methods section. The observed occurrence is the number of reported EC numbers associated with the query RDM pattern in the database. If the prediction is performed with a partial matching of the RDM pattern, the confidence level of prediction results are also shown on the output page. In this example, the ternary ‘R:D:M’ indicates the highest confidence prediction result, followed by the pair ‘R:D’, ‘D:M’, or ‘R:M’, and the singlets ‘R’, ‘D’ and ‘M’.

Fig. 4.

A screenshot of the output page.

In this page there is also a link to related reactions sharing the same RDM patterns with the query, through which the users can reach the corresponding enzyme genes involved with the enzymatic reaction of interest.

4.3 Edit

The user can manually modify the alignment, if needed. Clicking the ‘Edit alignment’ button in the output page brings the user to the edit mode, where the user can change the matched atoms in the graph alignment by inserting or deleting the atom types. After editing the alignment and clicking the ‘Save & Predict’ button, the user can carry out the EC number prediction again based on the refined RDM pattern. The user can also update the graph alignment image by clicking on the ‘update images’ button and obtain the result of the EC number prediction in the next round.

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Although our method gave correct results in the cross validation trials in most cases, it is valuable to examine the cases where the query has no hit in the first layer and was passed to the lower layers, or where the output conflicts with the official EC classification (Table 4). Basically, the reason the query has no hit in the first layer is that the reaction type was rare. For example, E-zyme concluded 4.1.1 for the three pairs RP02699 (crotonoyl-CoA and glutaconyl-1-CoA), RP10307 (acetaldehyde and 3-oxopropanoate) and RP03109 [3-(4-methylpent-3-en-1-yl)pent-2-enedioyl-CoA and geranoyl-CoA], of which the first two were correct while the true EC sub-subclass for the last one was 6.4.1. These pairs had no hit in the first layer because the reaction pattern was rare; the original definition of the EC 4.1.1 is the elimination reaction of carboxylate group into a carbon dioxide with the concomitant production of a double bond, while the first two are exceptions (they do not generate double bonds). The output for the last one is due to the same reaction patterns. Elimination or incorporation of carboxylate (EC 4.1.1) is not usually reversible. Although the last one is known to be synthetic (EC 6), the single mode does not give any clue on whether the reaction runs synthetic or degradable directions, which will have to be considered from the viewpoints of organic chemistry or enzymology.

Interpretation of conflicting cases is not completely performed without expert knowledge. For example, the pair RP01869 (glycoprotein and N-palmitoylglycoprotein) was given 2.5.1 by E-zyme while the true EC was 2.3.1, for which we have to conclude that the original reaction equation was incorrect. The pairs RP01169 (beta-alanine and beta-alanopine) and RP10092 [glutathione and S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione] were given 3.5.3 while they belong to EC 1.5.1 and EC 2.5.1, respectively. The former is similar to the reaction EC 3.5 in terms that a C–N bond is cut with the incorporation of a water molecule, however, we should admit the result was wrong because the reaction is oxidative and we have no evidence that the reaction intermediate includes amidines. The latter cannot belong to EC 3.5 because it cuts a C–S bond, but the E-zyme had a wrong conclusion because the prediction was done in the D:M layer and the R-atom was ignored.

The subclass EC 2.5 currently has only one sub-subclass EC 2.5.1, despite the very broad definition of enzymes transferring alkyl or aryl groups other than a methyl group. This subclass contains miscellaneous enzymes and includes several reactions for which the classification may have to be reviewed. For example, the pair RP02857 (thiamin monophosphate and 2-methyl-4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-pyrimidine diphosphate) is classified into EC 2.5.1 based on the interpretation that an alkyl group is transferred, however, it can also be interpreted as a synthesis of C–N bond with consumption of a phosphate bond (similar to phospholysis). Synthesis of a bond with production of a water molecule is a reverse reaction of hydrolysis, and is given an individual class EC 3; however, phospholysis and its reverse reaction are not given any class despite of the similarity to hydrolysis in the viewpoint of organic reaction mechanisms. This inequality of classification criteria results in the pair RP01988 (thiamin and 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine) being classified into EC 3.5.99, hydrolysis of a C–N bond other than peptide or amide, despite that the only difference is a water molecule instead of a phosphate. The pair RP03398 (porphobilinogen and hydroxymethylbilane) comes from a reaction where the same reaction type as EC 3.5.99 occurs successively but EC 2.5.1 is actually given, which also indicate that these three reaction should be checked if they are to be classified into the same sub-subclass.

In this article we proposed a new method to predict the EC sub-subclass based on our original biochemical transformation patterns called ‘RDM patterns’, and developed a web-server called ‘E-zyme’ which enables us to automatically assign the potential EC sub-subclasses to given reactant pairs or uncharacterized reactions. The originality of the proposed method is in its multi-layered partial template matching by comparing the query RDM pattern with template RDM patterns related with known EC numbers, and weighted major voting scheme for selecting appropriate EC numbers using reaction similarity. Cross-validation experiments showed that the proposed method achieves both high coverage and high prediction accuracy at a practical level, outperforming the previous method, which is due to a multi-layer structure and reaction pattern profile, respectively.

The E-zyme system covers the practical situation where the whole reaction formula is not available. The single mode demonstrates the circumstance where researchers wish to identify enzymes for which only part of their properties are known. This option is valuable because it is rare that the full equation has already been revealed before the enzyme is identified. Especially when a reactant pair turns out to be in EC 1, EC 2, EC 4 or EC 5 reactions, the single mode provides a relatively precise answer.

There are several related works involving the EC number prediction. The use of self-organizing map has been proposed (Latino et al. 2008) based on the molecular maps of atom-level properties (Zhang and Aires-de-Sousa, 2005), but the method cannot be used when the whole reaction formula is not clearly known. Another related work is the GREP (Generator of Reaction Equation & Pathways) method to find all plausible enzyme reaction equations and the putative EC sub-subclasses simultaneously (Kotera et al., 2008). The difference between the GREP and the E-zyme methods is the situation with which the users are faced. The GREP method requires the pre-calculation and the full specification of reaction equations before the user inputs, and the user cannot define the chemical compounds that have not been registered in the database yet. On the other hand, the E-zyme system is designed for the putative enzyme reactions whose properties have not completely been identified yet, and the advantage over the GREP system is that the user can input any chemical compounds regardless of whether they have already been registered in the database or not. It would be interesting to integrate both the E-zyme and the GREP systems such that it can deal with various situations regarding to the enzyme identification standing on either side of informatics and wet experiments. For example, automatic reconstruction of multiple reactant pairs from a complete or partial reaction equation would lead to predicting the whole reaction equation from partial user input, which should improve the usability.

The current version of the E-zyme system can provide a link to the corresponding enzyme candidate genes. The next possible development involves specifying which genes are actually involved in the reaction of interest for a specific organism. We are currently working on an extension of the E-zyme system such that it can predict specific genes out of the enzyme candidate gene set from other experimental data in the transcriptome and proteome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Computational resources were provided by the Bioinformatics Center, Institute for Chemical Research and the Super Computer Laboratory, Kyoto University.

Funding: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Barrett AJ, et al. Enzyme Nomenclature. San Diego, California: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Darvas F. Predicting metabolic pathways by logic programming. J. Mol. Graphis. 1988;6:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson CM. Chemical space and biology. Nature. 2004;432:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature03192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LBM, et al. The university of minnesota biocatalysis/biodegradation database: the first decade. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D517–D521. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, et al. Development of a chemical structure comparison method for integrated analysis of chemical and genomic information in the metabolic pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11853–11865. doi: 10.1021/ja036030u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou BK, et al. Encoding microbial metabolic logic: predicting biodegradation. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;31:261–272. doi: 10.1007/s10295-004-0144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopman G, Tu M. Structure-biodegradability study and computer-automated prediction of aerobic biodegradation of chemicals. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1997;16:1829–1835. [Google Scholar]

- Kotera M, et al. Eliciting possible reaction equations and metabolic pathways involving orphan metabolites. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008;48:2335–2349. doi: 10.1021/ci800213g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotera M, et al. Computational assignment of the EC numbers for genomic-scale analysis of enzymatic reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16487–16498. doi: 10.1021/ja0466457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langowski J, Long A. Computer systems for the prediction of xenobiotic metabolism. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latino DA, et al. Genome-scale classification of metabolic reactions and assignment of EC numbers with self-organizing maps. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2236–2244. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeno AN, et al. Biochemical reactions network modeling: predicting metabolism of organic chemical mixtures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:5363–5371. doi: 10.1021/es0479991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShan DC, et al. Symbolic inference of xenobiotics metabolism. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2004;9:545–556. doi: 10.1142/9789812704856_0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobeli I, Thornton JM. A bioinformatician's view of the metabolome. BioEssays. 2006;28:534–545. doi: 10.1002/bies.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M, et al. Systematic analysis of enzyme-catalyzed reaction patterns and prediction of microbial biodegradation pathways. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:1702–1712. doi: 10.1021/ci700006f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell BR. Chemical genetics: ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2000;1:116–125. doi: 10.1038/35038557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talafous J, et al. META. 2. A dictionary model of mammalian xenobiotic metabolism. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1994;34:1326–1333. doi: 10.1021/ci00022a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipton KF, Boyce S. History of the enzyme nomenclature system. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:34–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QY, Aires-de-Sousa J. Structure-based classification of chemical reactions without assignment of reaction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005;45:1775–1783. doi: 10.1021/ci0502707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]