Abstract

Introduction

Immediate precursors of bone-resorbing osteoclasts are cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Particularly during clinical conditions showing bone loss, it would appear that osteoclast precursors are mobilized from bone marrow into the circulation prior to entering tissues undergoing such loss. The observed heterogeneity of peripheral blood monocytes has led to the notion that different monocyte subpopulations may have special or restricted functions, including as osteoclast precursors.

Methods

Human peripheral blood monocytes were sorted based upon their degree of proliferation and cultured in macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF or CSF-1) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (RANKL).

Results

The monocyte subpopulation that is capable of proliferation gave rise to significantly more multinucleated, bone-resorbing osteoclasts than the bulk of the monocytes.

Conclusions

Human peripheral blood osteoclast precursors reside in the proliferative monocyte subpopulation.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease that is characterized by joint inflammation and profound focal and generalized bone loss due to the action of osteoclasts [1,2]. Multinucleated osteoclasts derive from monocyte/macrophage lineage precursors; two key mediators controlling their development are macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF or CSF-1) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (RANKL) [3-5]. Human osteoclast precursors have been shown to be present at low frequency in normal peripheral blood [6-8]. It now appears that peripheral blood monocytes, which derive from bone marrow precursors, are heterogeneous as judged by criteria such as surface marker expression, size, and function [9]. For example, in the human, there is a minor subpopulation of monocytes which is CD14lo CD16+ [10] and which has been implicated in inflammation and cancer [11-13]; in the mouse, there is a lot of recent interest in monocyte subpopulations that appear to have different roles during inflammatory reactions as manifested, for example, by their ability to migrate to sites of inflammation [14]. Human osteoclast precursors have recently been shown to reside in the CD14+ CD16- monocyte subpopulation of normal donors [15]. Blood samples from psoriatic arthritis patients, particularly those with bone erosions visible on plain radiographs, exhibit an increase in osteoclast precursors compared with those from healthy controls [16]; these precursors were recently reported to reside in the CD14lo CD16+ monocyte subset, leading the authors to suggest that osteoclasts are derived from distinct monocyte subsets in these patients and in healthy individuals [17].

Human monocytes are commonly considered to be non-proliferating [18]; however, we and others have defined a subpopulation of human monocytes which is capable of proliferating in vitro (for example, in response to M-CSF) [19-25]. This population has been referred to as proliferative monocytes (PMs), which were shown recently to have the phenotype CD14+ CD16- CD64+ CD33+ CD13lo c-Fms+ prior to culture [25]. It was previously suggested that PMs might be able to migrate into inflamed tissues and possibly undergo local proliferation there [19,25]. During these prior phenotyping studies, it was noticed in passing that, following culture and sorting by flow cytometry, the PMs, from the few donors studied, could give rise to tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRAP+) multinucleated cells upon culture in M-CSF + RANKL [25]. Based on this preliminary observation and the likelihood that the PMs represent a relatively less mature monocyte population on account of their ability to proliferate, it was reasoned that they may retain differentiation capability and therefore contain the osteoclast precursors. We present evidence here for this concept for the peripheral blood from normal donors.

Materials and methods

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell isolation, CFSE labeling, and cell culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated following Ficoll centrifugation and labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate-succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes Inc., now part of Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as described previously [25]. CFSE-labeled PBMCs were seeded onto non-treated 100-mm dishes (Iwaki; Asahi Techno Glass Corporation, Funabasi City, Japan) at a concentration of 3 to 5 × 107 cells per dish and allowed to adhere overnight in alpha-minimum essential medium (α-MEM) (JRH Biosciences, now part of SAFC Biosciences, Lenexa, KS, USA) containing L-glutamine (2 mM; Invitrogen Corporation) and penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (Invitrogen Corporation). Non-adherent cells were washed away, and new medium was added (α-MEM containing 3% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [Hi-FBS]) (CSL, Parkville, Victoria, Australia) with M-CSF (8,000 U/mL) (Chiron, Emeryville, CA, USA). These cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 9 days with a change of medium and removal of non-adherent cells every 3 days.

Cell sorting

The CFSE-stained cells were incubated in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes and harvested by gentle scraping with a rubber policeman. Cells were resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS containing 1% FBS) (Invitrogen Corporation) and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Ajax Chemicals, Cheltenham, Victoria, Australia) at a density of 107 cells per millilitre. Propidium iodide solution (3 μL of 1 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added immediately prior to sorting. CFSE fluorescence levels were determined by flow cytometry. The appearance of a peak with high fluorescence intensity (CFSEhi) indicated the cells that had not divided. Half the fluorescence intensity (CFSElo) indicated cells that have undergone one division. The existence of multiple peaks in some samples indicated multiple cell divisions in those populations [25]. CFSE-labeled cells were then sorted using a FACSVantage SE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Osteoclast generation from peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Sorted cells were cultured at 3 × 104 cells per well (in α-MEM and 3% Hi-FBS) in M-CSF (8,000 U/mL; Chiron) with or without RANKL (50 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). These cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for up to 21 days; the culture medium, including the relevant mediators, was changed twice per week. For the bone resorption assay, bone slices (horse cortical femur) were added to the well prior to the addition of the cells.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining

Osteoclast differentiation was determined firstly by TRAP staining following fixation in formaldehyde and acetone/alcohol as described previously [26]. Briefly, following fixation, cells were stained with freshly prepared TRAP staining solution (naphthol AS-MX phosphate, fast red violet LB salt, and potassium sodium tartrate). Osteoclast formation was evaluated by counting the TRAP+ multinucleated (n ≥ 3) cells.

mRNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analyses

Cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 in 3 mL/well of medium (α-MEM and 3% Hi-FBS) in the presence of M-CSF (8,000 U/mL) with or without RANKL (50 ng/mL) in 6-cm tissue culture dishes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were incubated for 14 days with a complete change of medium every 3 to 4 days. Total RNA was isolated with the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer. cDNAs were synthesized as described previously [27]. Pre-Developed TaqMan Assay Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Scoresby, Victoria, Australia) were used for cDNA sequence analysis for calcitonin receptor (CTR) and cathepsin K (Cath K). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses were used to quantify transcripts with the ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) as described previously [27]. For the PCR analyses, fluorescence from each sample was measured once each cycle during PCR and plotted against cycle number; the earlier a signal appeared (at a lower cycle number), the higher the concentration of the template. The cycle threshold (Ct) number was used to indicate gene expression.

Pit formation assay

Cells were removed from bone slices by brief sonication (approximately 30 seconds) and lysed in 1% Triton-X 100 for 30 minutes. Haematoxylin was applied to the resorbed surface of each slice for 1 minute and then the slices were washed three or four times with tap water. The residual stain was removed by wiping against absorbent paper. Resorption was observed by transmission light microscopy. Total pit area and total bone area were measured in 10 randomly selected areas for two or three bone slices by the Scion Image analysis program (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA), and the percentage pit area in each group was calculated [28].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. Significant differences were determined using the paired Student t test; a P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Proliferative monocytes contain precursors of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive multinucleated cells

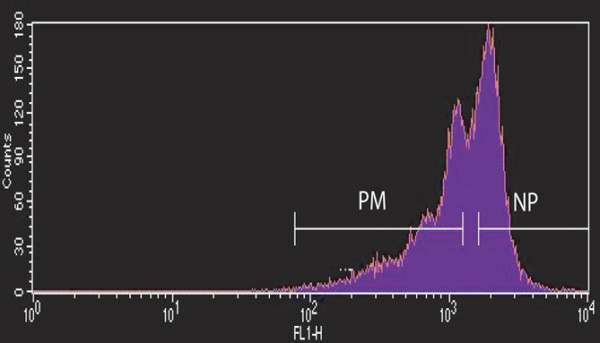

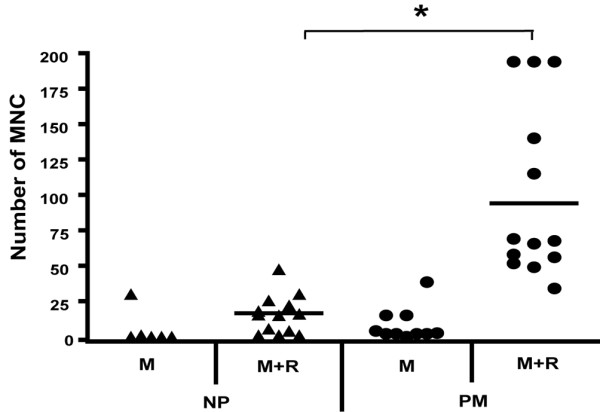

After culture in M-CSF, adherent, CFSE-labeled PBMCs could be sorted, based on their differing fluorescence intensities due to the number of cell divisions, into the PM and non-proliferative (NP) populations [25] (Figure 1). Preliminary data using PBMCs from three donors indicated that the former, predominantly spindle-shaped, population contained the bulk of the precursors which could be converted by culture in M-CSF + RANKL into TRAP+ multinucleated cells with more intense TRAP staining (that is, possibly osteoclasts) [25]. In a more complete study, we now present data (Figure 2) for the number of TRAP+ multinucleated (n ≥ 3) cells obtained from PBMCs from 13 donors and it can be seen that in general there were more of such cells derived from the PM population (P < 0.001) than from the NP monocyte population, an effect requiring the presence of RANKL; some multinucleated (n ≥ 3) cells could be observed even at day 7 in the PM cultures in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Sorting proliferative monocyte (PM) and non-proliferative (NP) population cells after carboxyfluorescein diacetate-succinimidyl ester (CFSE) labeling and culture. CFSE-labeled peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured in alpha-minimum essential medium + 3% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum containing macrophage colony-stimulating factor (8,000 U/mL) in non-treated dishes for 9 days. The adherent cells were then sorted based on their CFSE fluorescence intensity as PM (CFSElo) and NP (CFSEhi) populations [25].

Figure 2.

Proliferative monocytes (PMs) contain precursors of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRAP+) multinucleated cells (MNCs). Non-proliferative (NP) and PM subpopulations from 13 donors, sorted as in Figure 1, were cultured in duplicate or triplicate cultures in macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (8,000 U/mL) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (RANKL) (50 ng/mL) for 21 days; because insufficient cells were available, the two starting populations from fewer donors were also cultured in M-CSF alone. TRAP+ MNCs were counted. The mean number of such cells was significantly higher in the PM-derived cells cultured in M-CSF and RANKL compared with the NP-derived population (*P < 0.001). M, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; R, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand.

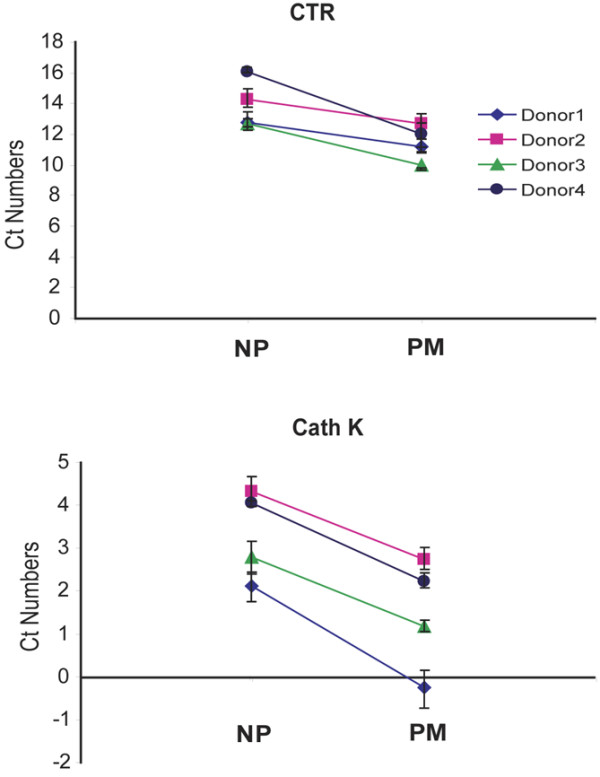

Higher osteoclast-associated gene expression in the proliferative monocyte population following culture in M-CSF and RANKL

Even though it was presented above that significantly more TRAP+ multinucleated cells can be obtained from the PM population, actual osteoclast differentiation needs to be confirmed as osteoclasts and macrophage polykaryons are morphologically similar [29]; in addition, TRAP staining does not distinguish very well between such populations in the human. We therefore firstly measured the expression of certain genes whose products are associated with osteoclast function. In Figure 3, the results from four donors for CTR and Cath K mRNA expression following culture in M-CSF + RANKL for 14 days are provided; it can be noted that there was significantly more expression of these osteoclast-specific genes from the PM population, which required RANKL to be present (data not shown). Consistent again with the greater osteoclastogenic potential of the PMs, their progeny, following culture in M-CSF + RANKL, had significantly greater RANK expression when measured at 14 days, at least at the gene level, when compared with that from the NP cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Osteoclast gene expression in differentiated proliferative monocyte (PM) and non-proliferative (NP) subpopulations. NP and PM subpopulations, sorted as in Figure 1, were cultured for 14 days in macrophage colony-stimulating factor (8,000 U/mL) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (50 ng/mL). Calcitonin receptor (CTR) and cathepsin K (Cath K) mRNA expression were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Samples from four individual donors were tested in triplicate, and data were normalized to 18S expression for each gene. Values are means of cycle threshold (Ct) numbers that were obtained in each sample ± standard error. The mean values for the PM population were significantly lower than those for the correspondingly treated NP population from the same donor (P ≤ 0.05).

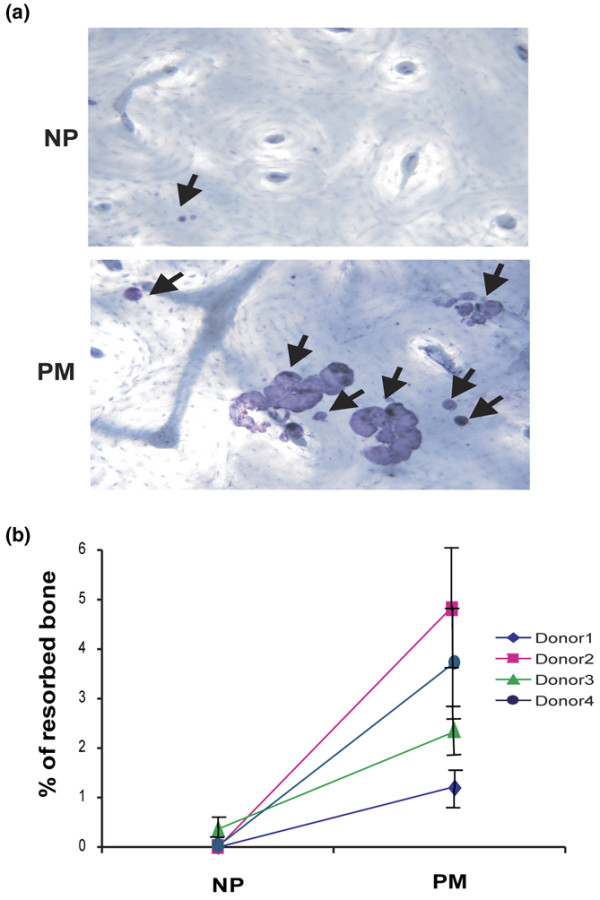

Higher bone resorption in the proliferative monocyte population following culture in M-CSF and RANKL

To confirm the functional activity of the multinucleated cells produced, bone resorption was measured next. The PM and NP populations were cultured in tissue culture dishes containing bone slices in the presence of M-CSF + RANKL. After 3 weeks, numerous resorption lacunae were found distributed over the surface of the bone slices in the PM cultures. However, only a few small resorption pits were observed in the bone slices cultured with NP cells under the same conditions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Precursors of bone-resorbing cells reside in the proliferative monocyte (PM) population. Sorted non-proliferative (NP) and PM populations (Figure 1) were cultured on bovine bone (3 × 104 cells per slice) for 21 days in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (8,000 U/mL) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (50 ng/mL). (a) The bone slices were stained with haematoxylin (magnification × 200). Arrows indicate pits on the bone surface. (b) Resorption pit area measured for four donors (see 'Higher bone resorption in the proliferative monocyte population following culture in M-CSF and RANKL' section). Values are means of percentage of resorbed bone ± standard error. For each donor, the mean values for the PM group are significantly greater than those for the correspondingly treated NP cells (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Under steady-state conditions, osteoclastogenesis and bone remodeling occur mainly in the bone marrow. Osteoclast precursors can be mobilized from bone marrow into blood and then into tissues, particularly in some conditions involving bone loss at diseased sites (for example, RA) [30,31]. At an early stage of differentiation, they are also able to give rise to different myeloid populations [32], whereas at a later stage their differentiation involves M-CSF-dependent action on c-Fms+ populations [33].

The heterogeneity of peripheral blood monocytes has led to the concept that there may be distinct subpopulations of cells with specialized functions [10,14,34,35]. For example, for the human, it is known that only a small proportion of monocytes can differentiate into osteoclasts [36,37]. Likewise, it is known that a small proportion of CD14+ human monocytes (that is, PMs) can proliferate in vitro [19,25]; because of their ability to proliferate, it was reasoned that this less mature population, possibly representing cells recently mobilized from bone marrow, may be able to differentiate into different macrophage lineage populations, such as osteoclasts, under appropriate conditions.

Taking advantage of the relative ability of monocyte populations to undergo proliferation, we were able to show above that, for the blood from 13 donors, osteoclast precursors reside predominantly in the PM population and could be detected even after proliferation in M-CSF. Following further culture in M-CSF and RANKL, the resultant population containing the multinucleated progeny showed increased expression of certain osteoclast markers (CTR, Cath K, and RANK) and an ability to resorb bone. These findings are consistent with the concept that the PMs represent a less mature population, when compared with the bulk of the human peripheral blood monocytes [19-21], with some cells in the PM fraction at least retaining an ability to differentiate into osteoclasts. The data presented are consistent with prior observations that both the PM population [19,25] and osteoclast precursors [15] from normal individuals reside in the CD14+ CD16- monocytes rather than in the CD14lo CD16+ population, that osteoclastic cells can be generated from proliferating dendritic cell precursors in human peripheral blood [38], and that there is an early increase in the percentage of human peripheral blood osteoclast precursors entering S phase during their in vitro differentiation in M-CSF + RANKL [39]. It is possible that the PMs can differentiate while in the blood into NP monocytes with reduced proliferative and differentiation potential, perhaps under the influence of circulating M-CSF.

It is intriguing that, in psoriatic arthritis, the opposite finding has been made in that the increased numbers of peripheral blood osteoclast precursors noted were located in the CD16+ population [17]. It would be worth knowing whether the PM population also increases in this and perhaps other inflammatory conditions and whether they begin to express higher CD16 levels in vivo. We suggest again [25] that functional criteria, such as PM status, have an advantage over surface marker phenotyping in that they avoid the difficulty in defining, for example, for monocyte populations whether modulation in the expression of a particular surface marker reflects differentiation or activation.

Conclusion

In summary, it has been shown here that human peripheral blood osteoclast precursors reside in the PM subpopulation, which is presumably a relatively less mature subpopulation and therefore possibly recently mobilized from bone marrow [19-21]. It has been proposed before [19-21,25] that, upon migration into inflammatory lesions, the PMs may contribute to the local macrophage proliferation which can be observed [40,41]. It is also possible that they could reside as osteoclast precursors in the synovial macrophage population within RA joints [30] which have been shown capable of differentiation into osteoclasts [42,43].

Abbreviations

α-MEM: alpha-minimum essential medium; Cath K: cathepsin K; CFSE: carboxyfluorescein diacetate-succinimidyl ester; CTR: calcitonin receptor; FBS: fetal bovine serum; Hi-FBS: heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum; M-CSF: macrophage colony-stimulating factor; NP: non-proliferative; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PM: proliferative monocyte; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; RANK: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand; TRAP: tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RL designed and performed the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. PDK performed the statistical analysis. JAH supervised the study and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant and a Senior Principal Research Fellowship (JAH) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. We thank Alice Holloway for sorting the cells, Felix Clanchy and John Roinotis for providing PBMCs, and Rifa Sallay for editing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Roya Lari, Email: royalari@gmail.com.

Peter D Kitchener, Email: p.kitchener@unimelb.edu.au.

John A Hamilton, Email: jahami@unimelb.edu.au.

References

- Romas E, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ. Involvement of receptor activator of NF[kappa]B ligand and tumor necrosis factor-[alpha] in bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Bone. 2002;30:340–346. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I, Bolon B, Tafuri A, Morony S, Capparelli C, Li J, Elliott R, McCabe S, Wong T, Campagnuolo G, Moran E, Bogoch ER, Van G, Nguyen LT, Ohashi PS, Lacey DL, Fish E, Boyle WJ, Penninger JM. Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature. 1999;402:304–309. doi: 10.1038/46303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller K, Wong B, Fox S, Choi Y, Chambers TJ. TRANCE is necessary and sufficient for osteoblast-mediated activation of bone resorption in osteoclasts. J Exp Med. 1998;188:997–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Tamura T, Akatsu T, Stanley ER, Kurokawa T, Suda T. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor is indispensable for both proliferation and differentiation of osteoclast progenitors. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:257–263. doi: 10.1172/JCI116179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Yamaguchi K, Yasuda H, Shima N, Morinaga T, Toyama Y, Yabe Y, Higashio K, Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor (ODF) induces osteoclast-like cell formation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:199–204. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JM, Neale S, Fujikawa Y, McGee JO, Athanasou NA. Human osteoclast formation from blood monocytes, peritoneal macrophages, and bone marrow cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;62:527–531. doi: 10.1007/s002239900473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalhoub V, Elliott G, Chiu L, Manoukian R, Kelley M, Hawkins N, Davy E, Shimamoto G, Beck J, Kaufman SA, Van G, Scully S, Qi M, Grisanti M, Dunstan C, Boyle WJ, Lacey DL. Characterization of osteoclast precursors in human blood. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:501–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grage-Griebenow E, Flad HD, Ernst M. Heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock H. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanaka N, Yamamura M, Aita T, Morita Y, Okamoto A, Kawashima M, Iwahashi M, Ueno A, Ohmoto Y, Makino H. CD14+, CD16+ blood monocytes and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2578–2586. doi: 10.1002/art.10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nockher WA, Scherberich JE. Expanded CD14+ CD16+ monocyte subpopulation in patients with acute and chronic infections undergoing hemodialysis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2782–2790. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2782-2790.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh MN, Goldman SJ, LoBuglio AF, Beall AC, Sabio H, McCord MC, Minasian L, Alpaugh RK, Weiner LM, Munn DH. CD16+ monocytes in patients with cancer: spontaneous elevation and pharmacologic induction by recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1995;85:2910–2917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderkotter C, Nikolic T, Dillon MJ, Van Rooijen N, Stehling M, Drevets DA, Leenen PJ. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172:4410–4417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano Y, Nanki T, Hayashida K, Taniguchi K, Miyasaka N. Identification of a human peripheral blood monocyte subset that differentiates into osteoclasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R152. doi: 10.1186/ar2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchlin CT, Haas-Smith SA, Li P, Hicks DG, Schwarz EM. Mechanisms of TNF-alpha- and RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in psoriatic arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:821–831. doi: 10.1172/JCI16069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y, Schwarz E, Mensah K, Durham R, Shan T, Ritchlin CT. Osteoclasts are derived from distinct monocyte subsets in psoriatic arthritis patients and healthy individuals. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56 Suppl 1:S249. [Google Scholar]

- van Furth R, Raeburn J, van Zwet T. Characteristics of human mononuclear phagocytes. Blood. 1979;54:485–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnin M, Hamilton JA, Moss ST. Characterization of a CSF-induced proliferating subpopulation of human peripheral blood monocytes by surface marker expression and cytokine production. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:953–960. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss ST, Hamilton JA. Proliferation of a subpopulation of human peripheral blood monocytes in the presence of colony stimulating factors may contribute to the inflammatory process in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Immunobiology. 2000;202:18–25. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(00)80048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnin M, Hamilton JA, Moss ST. Direct comparison of the effects of CSF-1 (M-CSF) and GM-CSF on human monocyte DNA synthesis and CSF receptor expression. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:417–423. doi: 10.1089/107999099314126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Por SB, Stanley ER, Breit SN. Monocyte proliferation in a cytokine-free, serum-free system. J Immunol Methods. 1992;153:201–212. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90323-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung DL, Hamilton JA. Regulation of human monocyte DNA synthesis by colony-stimulating factors, cytokines, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Blood. 1992;79:1972–1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson-Miller CL, Brennan JK, Abboud CN. Examination of survival, proliferation and cell surface antigen expression of human monocytes exposed to macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) Int J Cell Cloning. 1990;8:346–356. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530080503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clanchy FIL, Holloway AC, Lari R, Cameron PU, Hamilton JA. Detection and properties of the human proliferative monocyte subpopulation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:757–766. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0905522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JM, Whitty GA, Byrne RJ, Gillespie MT, Hamilton JA. The generation of highly enriched osteoclast-lineage cell populations. Bone. 2002;30:164–170. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lari R, Fleetwood AJ, Kitchener PD, Cook AD, Pavasovic D, Hertzog PJ, Hamilton JA. Macrophage lineage phenotypes and osteoclastogenesis – complexity in the control by GM-CSF and TGF-beta. Bone. 2007;40:323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakikawa T, Shioi A, Hino M, Inaba M, Nishizawa Y, Tatsumi N, Morii H, Otani S. Thrombopoietin inhibits in vitro osteoclastogenesis from murine bone marrow cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4160–4166. doi: 10.1210/en.138.10.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JM, Morfis M, Lam MH, Elliott J, Kartsogiannis V, Williams ED, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ, Sexton PM. Calcitonin receptor antibodies in the identification of osteoclasts. Bone. 1999;25:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L, Schwarz EM, Boyce BF. Osteoclast precursors, RANKL/RANK, and immunology. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N, Kotake S, Kamatani N, Takahashi N, Suda T. The molecular mechanism of osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:281–289. doi: 10.1186/ar431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman GD. Cell biology of the osteoclast. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(99)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X-M, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, Sylvestre V, Stanley ER. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99:111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Mak KL, Chen LY, Chou MP, Ho CK. Heterogeneity of human blood monocyte: two subpopulations with different sizes, phenotypes and functions. Immunology. 1992;77:298–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa Y, Quinn JM, Sabokbar A, McGee JO, Athanasou NA. The human osteoclast precursor circulates in the monocyte fraction. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4058–4060. doi: 10.1210/en.137.9.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey HM, Flanagan AM. Human osteoclasts derive from CD14-positive monocytes. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:167–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivollier A, Mazzorana M, Tebib J, Piperno M, Aitsiselmi T, Rabourdin-Combe C, Jurdic P, Servet-Delprat C. Immature dendritic cell transdifferentiation into osteoclasts: a novel pathway sustained by the rheumatoid arthritis microenvironment. Blood. 2004;104:4029–4037. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauli G, Rimondi E, Corallini F, Fadda R, Capitani S, Secchiero P. MDM2 antagonist Nutlin-3 suppresses the proliferation and differentiation of human pre-osteoclasts through a p53-dependent pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1621–1630. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutila MA, Banks KL. Locally dividing macrophages in normal and inflamed mammary glands. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;66:615–624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof RJ, Zafiropoulos D, Hamilton JA, Campbell IK. Exacerbation of acute inflammatory arthritis by the colony-stimulating factors CSF-1 and granulocyte macrophage (GM)-CSF: evidence of macrophage infiltration and local proliferation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119:361–367. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danks L, Sabokbar A, Gundle R, Athanasou NA. Synovial macrophage-osteoclast differentiation in inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:916–921. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.10.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos IE, Sabokbar A, Wordsworth BP, Carr A, Ferguson DJ, Athanasou NA. Synovial fluid macrophages are capable of osteoclast formation and resorption. J Pathol. 2006;208:35–43. doi: 10.1002/path.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]