Uridine phosphorylase from S. typhimurium was expressed and purified and cocrystallized with the drug 5-fluorouracil. The crystals diffracted X-rays to 2.2 Å resolution using synchrotron radiation.

Keywords: uridine phosphorylase, 5-fluorouracil, Salmonella typhimurium

Abstract

Uridine phosphorylase (UPh; EC 2.4.2.3) catalyzes the phosphorolytic cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond of uridine to form ribose 1-phosphate and uracil. This enzyme also activates pyrimidine-containing drugs, including 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In order to better understand the mechanism of the enzyme–drug interaction, the complex of Salmonella typhimurium UPh with 5-FU was cocrystallized using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method at 294 K. X-ray diffraction data were collected to 2.2 Å resolution. Analysis of these data revealed that the crystal belonged to space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 158.26, b = 93.04, c = 149.87 Å, α = γ = 90, β = 90.65°. The solvent content was 45.85% assuming the presence of six hexameric molecules of the complex in the unit cell.

1. Introduction

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used in chemotherapeutic regimens in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies, including oesophageal, gastric, colon and pancreatic tumours, as well as breast cancer for several decades (Kemeny, 1987 ▶; Huang et al., 2007 ▶). This drug competes with uracil for interaction with thymidylate synthase. 5-FU interferes with DNA and RNA synthesis, thereby causing cell death. Furthermore, 5-halogen-containing derivatives of uracil are also used as antimicrobial agents. Synergism of 5-FU with antibacterial agents such as ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefotiam, piperacillin and netilmicin has been shown (Price et al., 1965 ▶; Gieringer et al., 1986 ▶; Yamashiro et al., 1986 ▶). However, toxicity towards haematopoietic cells, skin, heart and neurons can limit the therapeutic efficacy of 5-FU and structurally similar drugs (Peters & van Groeningen, 1991 ▶). Uridine phosphorylase (UPh) catalyzes the phosphorolytic cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond in uridine to produce ribose 1-phosphate and uracil (Leer et al., 1977 ▶; Vita et al., 1986 ▶). This enzyme activates pyrimidine-based drugs, including 5-FU (Cao et al., 2002 ▶; Caradoc-Davies et al., 2004 ▶). Therefore, studies of the structure of UPh bound to 5-FU should be instrumental in future modifications aimed at the design of 5-FU derivatives with lower general toxicity and retained antitumour and antimicrobial potencies (Iigo et al., 1990 ▶; Temmink et al., 2006 ▶; Matsusaka et al., 2007 ▶).

2. Protein expression and purification

Salmonella typhimurium UPh (StUPh) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as reported elsewhere (Molchan et al., 1998 ▶; Dontsova et al., 2004 ▶). The Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strain was transformed with the recombinant plasmid and grown on solid LB agar for 12 h at 310 K. Protein synthesis was stimulated with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. The biomass was sonicated, ammonium sulfate was added to precipitate the proteins and the pellets were dissolved in buffer (pH 7.2) containing 50 mM KH2PO4 and 0.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Further steps of StUPh purification were performed using chromatography on butyl Sepharose as a first step and Q-Sepharose as the final step. The enzymatic activity was 280 units per milligram of purified protein. The homogeneity of the purified StUph was 96% as determined by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis.

3. Crystallization of the StUph–5FU complex

Crystals of the complex of StUph with 5-FU (EBEWE Pharma, Austria) were obtained by cocrystallization (Fig. 1 ▶). Crystallization was performed on siliconized glass slides (Hampton Research, USA) in Linbro plates at 294 K using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The reservoir solution (0.5 ml) consisted of 0.34 ml 0.1 M Tris–maleate–NaOH buffer pH 5.5 and 0.16 ml 40%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350. The crystallization drop contained 2 µl StUph solution (11.3 mg ml−1) in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.3, 2 µl H2O, 1.3 µl reservoir solution, 2 µl 100 mM 5-FU and 0.3 µl 2-propanol. Crystals of dimensions 0.07 × 0.3 × 0.5 mm were obtained after 1–2 weeks and were used for X-ray diffraction analysis.

Figure 1.

Crystal of StUPh complexed with 5-FU.

4. X-ray analysis

The X-ray data set (Table 1 ▶) was collected upon irradiation of StUPh–5FU crystals under cryogenic conditions (100 K) on beamline 14.2 at BESSY, Berlin, Germany. The wavelength was 0.9184 Å. A CHESS CCD detector was used with an oscillation range Δϕ of 0.5° and a crystal-to-detector distance of 240 mm. Prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen, the crystals were transferred into cryoprotectant solution containing 100 mM Tris–maleate–NaOH buffer pH 5.5, 25%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350 and 20%(v/v) anhydrous glycerol. All data were processed and scaled using XDS (Kabsch, 1988 ▶).

Table 1. Statistics of X-ray data.

Values in parentheses are for the last resolution shell.

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.918 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Oscillation (°) | 0.5 |

| Space group | C2 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 158.26, b = 93.04, c = 149.87, α = γ = 90, β = 90.65 |

| Molecules per unit cell | 6 |

| VM (Å3 Da−1) | 2.27 |

| Solvent content (%) | 45.85 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 30.0–2.2 (2.25–2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 90.2 (79.3) |

| No. of reflections | 324446 |

| No. of unique reflections | 99573 (7124) |

| Robserved (%) | 6.8 (55.6) |

| Rexpected (%) | 7.0 (55.3) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 12.67 (2.16) |

| Rmeas | 0.08 (0.66) |

| Rmerge | 0.017 (0.47) |

| Redundancy | 3.26 (3.24) |

300 images were obtained during the collection of X-ray diffraction data. All data were indexed, merged and processed using the XDS program with XYCORR, INIT, COLSPOT, IDXREF, DEFPIX, XPLAN, INTEGRATE and CORRECT options. For a semi-automatic determination of the space group, the minimal value of the XDS ‘quality of fit’ function was used. The crystals of the StUPh–5-FU complex belonged to space group C2. Detailed data statistics are presented in Table 1 ▶.

The structure was resolved by the molecular-replacement technique using the Phaser program with rigid-body refinement option (McCoy, 2007 ▶). X-ray diffraction data from 10 to 2.5 Å resolution were used in this step. The X-ray structure of monomer A only of ligand-free StUPh at 1.76 Å resolution (Timofeev et al., 2007 ▶; PDB code 2oxf) was utilized as a search model. Water molecules were removed from the model. Six full homohexamer molecules were found in the unit cell. The Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1968 ▶) was 2.27 Å3 Da−1 and the solvent content was 45.85% (Table 1 ▶). Only one solution was evident, with an R factor of 37.64% and a correlation coefficient R corr of 76.95%.

To improve the phase model, one macrocycle of simulated annealing using the phenix.refine module of PHENIX (Adams et al., 2002 ▶) was performed in the temperature range 12 000–300 K with 50 K steps and resolution 10–2.2 Å. Before refinement, 5% of the observations were chosen at random and set aside for cross-validation analysis and to monitor the various refinement strategies. Next, σA-weighted electron-density maps with coefficients (2|F o| − |F c|) and (|F o| − |F c|) were obtained using PHENIX. Using the (|F o| − |F c|) electron-density map in the Coot program (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶), we identified 5-FU molecules and water molecules localized in the close vicinity of the 5-FU molecules. After two cycles of restrained refinement in REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▶) and the synthesis of σA-weighted (2|F o| − |F c|) and (|F o| − |F c|) electron-density maps the R factor was 26.42% and R free was 29.24%.

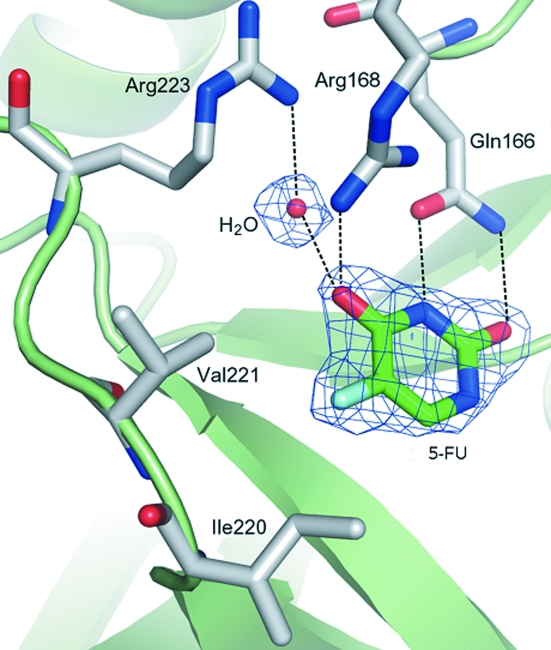

One uracil-binding site in StUph complexed with 5-FU and water is shown in Fig. 2 ▶. The cartoon representation was generated with PyMOL (DeLano, 2008 ▶). The drug and water bind to the following atoms of the amino-acid residues in the uracil-binding site: Arg223 NH1–water (2.85 Å), water–5-FU O4 (2.88 Å), Arg168 NH1–5-FU O4 (3.00 Å), Gln166 OE1–5-FU N3 (2.70 Å), Gln166 NE2–5-FU O2 (2.89 Å). Refinement of the structure is currently in progress and will be published elsewhere.

Figure 2.

Preliminary structure of the uracil-binding site in the StUPh–5-FU complex.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partially by RFBR and Kaluga region administration (grant No. 09-02-97519).

References

- Adams, P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Hung, L.-W., Ioerger, T. R., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Read, R. J., Sacchettini, J. C., Sauter, N. K. & Terwilliger, T. C. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cao, D., Russell, R. L., Zhang, D., Leffert, J. J. & Pizzorno, G. (2002). Cancer Res.62, 2313–2317. [PubMed]

- Caradoc-Davies, T. T., Cutfield, S. M., Lamont, I. L. & Cutfield, J. F. (2004). J. Mol. Biol.337, 337–354. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2008). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. http://www.pymol.org.

- Dontsova, M. V., Savochkina, Y. A., Gabdoulkhakov, A. G., Baidakov, S. N., Lyashenko, A. V., Zolotukhina, M., Errais Lopes, L., Garber, M. B., Morgunova, E. Y., Nikonov, S. V., Mironov, A. S., Ealick, S. E. & Mikhailov, A. M. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 709–711. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gieringer, J. H., Wenz, A. F., Just, H. M. & Daschner, F. D. (1986). Chemotherapy, 32, 418–424. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z., Guo, K. J., Guo, R. X. & He, S. G. (2007). Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int.6, 312–320. [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (1988). J. Appl. Cryst.21, 916–924.

- Kemeny, N. (1987). Semin. Surg. Oncol.3, 190–214. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leer, J. C., Hammer-Jespersen, K. & Schwartz, M. (1977). Eur. J. Biochem.75, 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iigo, M., Nishikata, K., Nakajima, Y., Szinai, I., Veres, Z., Szabolcs, A. & De Clercq, E. (1990). Biochem. Pharmacol.39, 1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matsusaka, S., Yamasaki, H., Fukushima, M. & Wakabayashi, I. (2007). Chemotherapy, 53, 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol.33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J. (2007). Acta Cryst. D63, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Molchan, O. K., Dmitrieva, N. A., Romanova, D. V., Errais Lopes, L., Debabov, V. G. & Mironov, A. S. (1998). Biochemistry (Mosc.), 63, 195–199. [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Peters, G. J. & van Groeningen, C. J. (1991). Ann. Oncol.2, 469–480. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Price, K. E., Bradner, W. T., Buck, R. E. & Lein, J. (1965). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.5, 481–487. [PubMed]

- Temmink, O. H., de Bruin, M., Laan, A. C., Turksma, A. W., Cricca, S., Masterson, A. J., Noordhuis, P. & Peters, G. J. (2006). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.38, 1759–1765. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Timofeev, V. I., Pavlyuk, B. F., Lashkov, A. A., Seregina, A. G., Gabdulkhakov, A. G., Vainshtein, B. K. & Mikhailov, A. M. (2007). Kristallografiya, 52, 1106–1113.

- Vita, A., Amici, A., Cacciamani, T., Lanciotti, M. & Magni, G. (1986). Int. J. Biochem.18, 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, Y., Fukuoka, Y., Yotsuji, A., Yasuda, T., Saikawa, I. & Ueda, Y. (1986). J. Antimicrob. Chemother.18, 703–708. [DOI] [PubMed]