Abstract

ATP-driven remodelling of initial RNA polymerase (RNAP) promoter complexes occurs as a major post recruitment strategy used to control gene expression. Using a model-enhancer-dependent bacterial system (σ54-RNAP, Eσ54) and a slowly hydrolysed ATP analogue (ATPγS), we provide evidence for a nucleotide-dependent temporal pathway leading to DNA melting involving a small set of σ54-DNA conformational states. We demonstrate that the ATP hydrolysis-dependent remodelling of Eσ54 occurs in at least two distinct temporal steps. The first detected remodelling phase results in changes in the interactions between the promoter specificity σ54 factor and the promoter DNA. The second detected remodelling phase causes changes in the relationship between the promoter DNA and the core RNAP catalytic β/β’ subunits, correlating with the loading of template DNA into the catalytic cleft of RNAP. It would appear that, for Eσ54 promoters, loading of template DNA within the catalytic cleft of RNAP is dependent on fast ATP hydrolysis steps that trigger changes in the β’ jaw domain, thereby allowing acquisition of the open complex status.

Keywords: ATPase, DNA melting, protein-DNA cross-linking, RNA polymerase, transcription regulation

Introduction

Gene expression is a fundamental process that is frequently controlled at the level of transcription initiation. The similarity in sequence and structure between bacterial and eukaryotic RNA polymerases (RNAPs) suggests that they share many functional states required to progress from initial promoter complexes to complexes competent for making RNA.1 Understanding the nature of the conformational changes that occur during transcription initiation and how they are controlled is important in elaborating how RNAPs work as intricate and regulated molecular machines.

A major adaptive response in bacteria relies upon regulation of gene expression at the DNA melting step.2,3 It requires RNAP containing the major variant σ54 promoter specificity factor and a specialised activator ATPase that belongs to the extended AAA+ (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) protein family. Transcription initiation from σ54-dependent promoters in bacteria is functionally analogous to enhancer-dependent initiation of eukaryotic RNAP II, which requires an input of energy from ATP hydrolysis provided by transcription factor IIH.4,5 The bacterial activator ATPase causes the active remodelling of the initial transcriptionally silent σ54-RNAP (Eσ54) promoter complex, termed the closed complex (CC), that otherwise persists. The activator ATPase remodels the Eσ54 CC to the transcriptionally proficient open complex (OC), in which the template DNA is found loaded within the catalytic cleft of RNAP.6-8 How ATP binding and hydrolysis by the activator ATPase are coupled to OC formation is only partially understood. Studying the interactions between the activator ATPase and Eσ54 has proven difficult due to the transient and dynamic nature of these interactions. Ground-state and transition-state analogues of ATP stabilise a highly conserved surface-exposed flexible σ54-interacting loop, termed the L1 loop (Supplementary Fig. 1; the “GAFTGA loop”), located within the AAA+ domain of the activator ATPase, apparently causing it to engage Eσ54.9-13 However, the information obtained on the changes brought about in Eσ54 by the activator ATPase is restricted since complexes formed in the presence of these ATP analogues are “trapped,” unable to progress to the OC status and therefore remain transcriptionally inactive.

Here we demonstrate that the ATP analogue ATPγS reacts slowly with the Escherichia coli σ54-dependent activator ATPase phage shock protein F (PspF) to yield ADP and can activate Eσ54 transcription. Using a site-specific DNA-protein cross-linking assay,14-16 we follow, in a time-resolved manner, complete conversion of one binary σ54 promoter complex and the initial Eσ54 CC into their remodelled states. The work provides evidence for a nucleotide-dependent temporal pathway leading to DNA melting, which involves a small set of σ54-DNA conformational states. We show that stimulation of OC formation by PspF1-275-ATPγS is dependent on the integrity of the L1 loop, and that nucleotide binding and subsequent hydrolysis cause changes in PspF1-275-DNA and σ54-DNA interactions that precede changes in RNAP β/β’-DNA interactions, with the latter being greatly limited by the slow hydrolysis rate. We also observe that compromising the functionality of the β’ jaw domain [by using the bacteriophage T7 transcription inhibitor gene protein 2 (gp2)] results in significantly reduced ATPγS-dependent, but not ATP-dependent, stimulation of OC formation. We thus provide evidence that at least two activator-dependent steps are required for productive OC formation and identify the β’ jaw domain as one structurally conserved flexible feature of RNAP associated with a kinetic barrier to OC formation.17 We propose that when ATP is used, relatively fast hydrolysis steps in the activator ATPase overcome this barrier by linking changes in the relationship between activator ATPase, σ54, and/or promoter DNA to major conformational reorganisations of the RNAP that accompany OC formation.

Results

ATPγS is hydrolysed by PspF1-275

OC formation by RNAPs is a multistep isomerisation process involving a number of intermediates, the characterisation of which has proved difficult due to their transient natures. For Eσ54, ground-state and transition-state ATP analogues (when bound to the activator ATPase) have allowed access to stable putative intermediates, but since these complexes are “trapped” and are therefore transcriptionally inactive, their relevance is uncertain.9-11,13 We reasoned that the poorly hydrolysable ATP analogue ATPγS may allow the initial ATP-bound form of the activator ATPase and early intermediates formed en route to the Eσ54 OC to be characterised (by slowing down one or more steps in the isomerisation process). Earlier studies suggested that ATPγS would function far less efficiently, if at all, in Eσ54-dependent OC formation.6,7,18 However, recently, it has been reported that ATPγS is slowly hydrolysed by certain AAA+ proteins, including another Eσ54 activator ATPase, NtrC1.10,19,20 For experimental simplicity, we used a structurally characterised form of PspF (AAA+ domain amino acids 1-275, PspF1-275), deleted for its DNA-binding domain, that is still capable of efficiently activating transcription from σ54-dependent promoters in vivo and in vitro from solution.12,21,22

To determine whether PspF1-275 can hydrolyse ATPγS to yield ADP, we performed in situ ADP-AlF “trapping” assays to monitor complex formation between Eσ54 and PspF1-275-ADP-AlF9. Previously, we have shown that a stable complex containing (E)σ54 and a hexameric form of PspF1-275 can be detected in the presence of the transition-state analogue ADP-AlF (formed in the presence of ADP, NaF, and AlCl3).9,12 Importantly, recently, it has also been shown that by substituting ADP with ATP (in the presence of NaF and AlCl3), we can form ADP-AlF trapped complexes, as ATP is hydrolysed by PspF1-275 to ADP23. We reasoned that if ATPγS is hydrolysed by PspF1-275, it also would support PspF1-275-ADP-AlF trapped complex formation. As shown in Fig. 1a, the level of trapped complex formation, and thus ADP production, from PspF1-275 in the presence of 0.2 mM ATPγS (lane 2) is significantly lower than that observed with 0.2 mM ATP (lane 1) after 5 min incubation time. However, when the reaction time is increased, allowing accumulation of ADP from ATPγS hydrolysis, the amount of trapped complex detected significantly increases (Fig. 1a, lanes 3-5). Importantly, in the absence of the trapping reagents (NaF and AlCl3), ATPγS hydrolysis does not result in the formation of a stable trapped complex (lane 6). Control reactions with a PspF1-275 mutant harbouring the Walker B motif substitution D107A, which has significantly reduced (<1% of wild-type (WT) activity) ATP hydrolysis activity,23,24 failed to form trapped complexes in the presence of ATPγS (data not shown). Furthermore, we observed that in ATPγS-soaked PspF1-275 crystals, ATPγS occupies the same position in PspF1-275 as ATP and AMP-PNP (Supplementary Fig. 122). In line with its slow hydrolysis rate, soaking crystals of PspF1-275 with 40 mM ATPγS did not lead to the crystals cracking.22

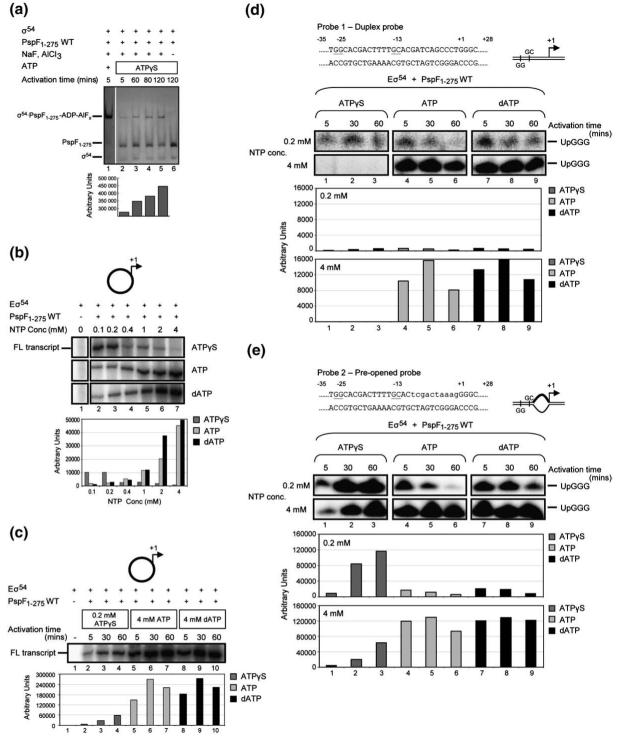

Fig. 1.

ATPγS is hydrolysed and supports full-length (FL) Eσ54 transcription. (a) In situ trapping reactions demonstrate that, given sufficient incubation times, PspF1-275-ATPγS (hydrolysed by PspF1-275 to ADP) supports the formation of an ADP metal/fluoride trapped complex. (b) Denaturing gels showing that PspF1-275-ATPγS can support Eσ54 transcription from the supercoiled S. meliloti nifH promoter, and the results of different ATPγS (lanes 2-7), ATP (lanes 8-13), and dATP (lanes 14-19) concentrations in the transcription assays. The activation time for reactions was 5 min. The FL transcript is as indicated. The relative amount of transcription product formed in the presence of ATPγS (light gray), ATP (dark gray), and dATP (black) is depicted in the bar graph below. (c) Denaturing gel showing transcription from the supercoiled nifH promoter by PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM ATPγS (lanes 2-4), 4 mM ATP (lanes 5-7), or 4 mM dATP (lanes 8-10) after 5 min, 30 min, and 60 min activation time. The FL transcript is as indicated. The bar graph is as indicated in (b). (d) Nucleotide sequence of the S. meliloti nifH duplex promoter probe (probe 1) used in this study. Underlined are the two consensus dinucleotide promoter elements GG (positions -26 and -25, with respect to the transcription start site at +1) and GC (positions -14 and -13), which characterise σ54-dependent promoters. The symbol used to represent this promoter probe is shown on the right. Abortive transcription gels showing the effect of increased activation time on Eσ54 OC formation with PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM or 4 mM ATPγS (lanes 1-3), 0.2 mM or 4 mM ATP (lanes 4-6), and 0.2 mM or 4 mM dATP (lanes 7-9) on probe 1. The relative number of productive OCs formed on probe 1 in the presence of ATPγS (dark gray), ATP (light gray), and dATP (black) following 5 min, 30 min, and 60 min activation time is indicated in the bar graph. The abortive transcript 5′ UpGGG is indicated. (e) As in (d), but using the pre-opened promoter probe (probe 2). Lower-case letters indicate non-complementary residues in probe 2.

We next determined that the turnover rate of PspF1-275 for ATPγS under similar conditions used for the transcription assays (see below and Materials and Methods) is 0.03 min-1 (±0.0005), which is approximately 1/1000th the rate observed with ATP. The slow hydrolysis rate of ATPγS is not the result of poor nucleotide binding since the affinities for ATP and ATPγS are likely to be similar.25 Importantly, since in vitro mutants of PspF1-275 with greatly reduced ATPase activity support OC formation, we suggest that the very low rates of hydrolysis associated with ATPγS would be sufficient for slowly making OCs.23 Overall, these data establish that ATPγS reacts slowly with PspF1-275 to yield ADP, and we subsequently use the term “slow hydrolysis” without defining which enzymatic step(s) are slower when compared to ATP hydrolysis.

PspF1-275-ATPγS supports Eσ54 transcription

We next investigated whether ATPγS can support in vitro transcription from the σ54-dependent Sinorhizobium meliloti nifH promoter on a supercoiled plasmid. Figure 1b (lane 2) demonstrates that Eσ54-dependent transcription can occur in the presence of PspF1-275 and ATPγS after 5 min activation time, the same time period when we observed a small amount of trapped complex formation (Fig. 1a, lane 2). Initially, we determined the optimal concentration of ATPγS that resulted in the maximum number of transcripts from competitor (heparin)-resistant OCs. Unlike ATP or dATP, which functions optimally at 4 mM25 (Fig. 1b, lane 7), the optimal concentration for ATPγS under the experimental conditions used is 0.2 mM (Fig. 1b, lane 3). Previously, it has been demonstrated that PspF1-275 functions in a mixed nucleotide state that is subject to inhibition by ATP at concentrations greater than 4 mM due to saturation of nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) binding sites by ATP.25,26 Since the rate of ATPγS hydrolysis appears much slower compared to that of ATP (Fig. 1a) or dATP, we expect that this would lead to different optimal nucleotide requirements.

Previously, we have shown that in the presence of an ATPase defective mutant PspF1-275 E108Q (1% of WT activity) and ATP, Eσ54 transcription is greatly improved upon increased activation periods.23 In line with this observation, Eσ54 transcription from the supercoiled nifH promoter significantly increased at longer activation times with PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 1c, lanes 2-4), more than 1000-fold above the level observed for control reactions in which ATPγS (data not shown) or PspF1-275 (lane 1) was omitted. These data are consistent with in situ trapping reactions, which demonstrate that more trapped complexes, and hence more ATPγS hydrolysis, are observed when the incubation time of PspF1-275 with ATPγS is increased (Fig. 1a, lanes 2-5). However, we note that the ATPγS-dependent transcript level is significantly lower than that observed in the presence of PspF1-275 and either ATP or dATP (Fig. 1c, lanes 5-7 and 8-10). Separate experiments show that the decrease in transcripts observed after 60 min activation time with either ATP or dATP is the result of NTP depletion (and nonoptimal nucleotide ratios) and the decay of preformed OCs (data not shown).

We suggest that the effective use of ATPγS in transcription activation (i.e., more transcripts formed at lower nucleotide concentrations; Fig. 1b, lane 3) is, in part, the result of a prolonged association between PspF1-275 and ATPγS, supporting a binding interaction with the Eσ54 CC. In contrast with either ATP or dATP, where hydrolysis occurs much more rapidly, we envisage that a greater proportion of hydrolysis occurs when PspF1-275 is not interacting with the Eσ54 CC, thereby inefficiently coupling nucleotide hydrolysis to OC formation.

Preopening the DNA promotes OC formation by PspF1-275-ATPγS

Using the supercoiled DNA template, slow hydrolysis of ATPγS clearly supports transcription activation by Eσ54. We next considered whether preopening the DNA could increase the amount of OCs formed by PspF1-275-ATPγS, as might occur if, for example, rapid hydrolysis is linked to DNA melting and/or loading of the opened DNA into the catalytic cleft of RNAP. Using abortive transcription assays (to measure heparin-resistant OC formation)27,28 with two promoter probes, a native linear duplex (Fig. 1d; probe 1), and a linear pre-opened probe (Fig. 1e; probe 2; mismatched between positions -10 and -1, thereby mimicking the conformation of the promoter within the Eσ54 OC),17,29 we determined whether the rate-limiting step in ATPγS-dependent OC formation by PspF1-275 occurs prior to, or after, DNA melting. Like the full-length transcription assays on the supercoiled template, the abortive transcription assays show that PspF1-275 and 4 mM ATPγS (lanes 1-3) are far less effective than PspF1-275 and either 4 mM ATP (lanes 4-6) or 4 mM dATP (lanes 7-9) in stimulating OC formation when the promoter DNA template is fully double-stranded (Fig. 1d, probe 1). At the lower 0.2 mM concentration (optimal for ATPγS), all the NTPs tested in the presence of PspF1-275 form similar numbers of OCs on the duplex probe, implying that limiting amounts of NTP hydrolysis occur in each case. We note that the rates of decay of OCs (as judged by a heparin challenge experiment) are similar whether they are formed using ATP, dATP, or ATPγS (data not shown), indicating that OCs formed in the presence of PspF1-275-ATPγS were indistinguishable from those formed in the presence of either PspF1-275-ATP or PspF1-275-dATP. This fact, and the rapid consumption of ATP or dATP but not ATPγS, can explain the loss of abortive transcripts at longer activation times with the former.

Strikingly, when using the pre-opened (-10 to -1) template (Fig. 1e, probe 2), the number of OCs formed in the presence of PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM or 4 mM ATPγS significantly increased (approximately 100-fold, or greater in the case of 4 mM ATPγS) and approached the number obtained with PspF1-275-ATP after 60 min activation time (Fig. 1e). Notably, the number of OCs formed by PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM or 4 mM ATP or dATP is also increased by preopening the promoter DNA, yet by only 10-fold. Native gel shift experiments demonstrated that the number of CCs formed on the pre-opened probe in the presence of PspF1-275 and either ATPγS or dATP is similar (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The number of OCs formed (as judged by 5 min of heparin challenge) is significantly lower than the number of CCs observed, indicating that some CCs remain available for potentially making more OCs, and so CC formation is not limiting. We note that the number of OCs formed by PspF1-275-ATPγS increases linearly over the three time points assayed in this study (5 min, 30 min, and 60 min) (Supplementary Fig. 2a, lanes 2-4), yet the number of OCs formed by PspF1-275-dATP is only linear at very early incubation time points (up to 2 min) (Supplementary Fig. 2a, lanes 5-13). Importantly, separate control reactions demonstrate that the reagents required to make OCs, including the promoter DNA concentration (Supplementary Fig. 2b), were not limiting, indicating that we would be able to detect an approximate 100-fold increase in OCs with either PspF1-275-ATP or PspF1-275-dATP if it were occurring. Taken together, these results suggest a role for rapid ATP hydrolysis-dependent steps in the loading of melted DNA within the catalytic cleft of the RNAP to form heparin (competitor)-resistant OCs.

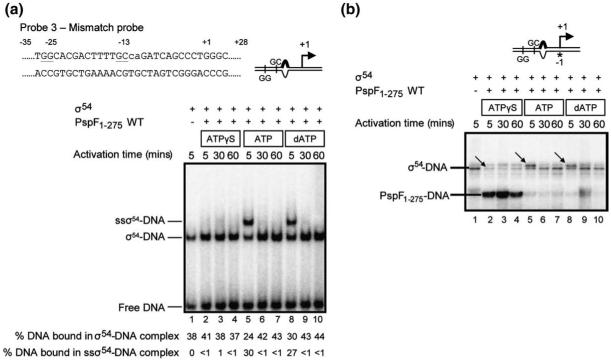

Determinants in PspF1-275 important for OC formation with ATPγS

In principle, the ability of PspF1-275-ATPγS to support competitor-resistant OC formation could be due simply to the ATPγS-bound form of PspF1-275 mimicking the ATP-bound state, rather than it being slowly hydrolysed. Determinants in PspF required for both ATP binding (Walker A motif)24 and ATP hydrolysis (Walker B motif)23 were found to be essential for OC formation on the pre-opened promoter when using PspF1-275 and either dATP or ATPγS (data not shown). Determinants that are important for coupling the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to isomerisation of the Eσ54 CC, in particular residues F85 and T866,21 (located within the GAFTGA motif of the σ54-interacting L1 loop; Supplementary Fig. 1), were also required for PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent stimulation of OC formation (Fig. 2a). Previous studies have demonstrated that the PspF1-275 mutants F85W and T86A were unable to interact with σ54, although their ability to hydrolyse ATP remained largely unaffected. Consistent with these findings, no abortive products on the pre-opened probe were detected when using PspF1-275 harbouring either F85W or T86A substitutions in the presence of dATP (Fig. 2a, lanes 2 and 4) or ATPγS (Fig. 2a, lanes 6 and 8). The T86S substitution, however, permits PspF1-275 to interact with σ54 whilst having no significant effect on ATPase activity, which explains its ability to stimulate OC formation (and hence abortive products) in the presence of dATP at a level similar to that of WT PspF1-275 (Fig. 2a, compare lanes 1 and 3). Significantly, T86S behaved differently in the presence of ATPγS (Fig. 2a, compare lanes 3 and 7), displaying a severely reduced ability (<1% of wild-type levels) to form OCs and hence activate transcription from the pre-opened promoter, but, with respect to ATPγS, had a modest effect on hydrolysis activity (80% of WT ATPγS hydrolysis activity levels). These data show that post-DNA melting steps that require rapid ATP hydrolysis are linked to the functional integrity of the L1 loop for efficient OC formation.

Fig. 2.

OC formation by PspF1-275-ATPγS is dependent on the β’ jaw domain. (a) Abortive transcription assays (see Materials and Methods) on pre-opened probe 2 demonstrating that separate determinants in PspF1-275 used for coupling the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to OC formation (T86A or S and F85W located within the σ54-interacting L1 loop) are required for PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent stimulation of OC formation. The percentage of WT PspF1-275 ATPase activity in the presence of ATP (dATP) or ATPγS is as indicated. (b) Abortive transcription assays on probe 2 demonstrating the sensitivity of the PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent stimulation of OC formation to the bacteriophage T7 transcription inhibitor gp2. Only when gp2 is added prior to activation (+gp2; lanes 15-17) is PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent OC formation affected. When gp2 is added after activation (+gp2*; lanes 18-20), no effect on OC formation is observed. Consistent with previous findings30 in the presence of PspF1-275-dATP, no effect of gp2 (lanes 4-9) on OC formation is observed. In (a) and (b), the abortive transcript 5′ UpGGG is indicated.

OC formation by PspF1-275-ATPγS requires the functional integrity of the β’ jaw domain

Stable OC formation by Eσ54 relies upon the structural integrity of the β’ jaw domain, which, together with the β’ clamp domain, forms a trough where the DNA downstream of the active site is located within the OC. Thus, deletion of the β’ jaw (E. coli β’ residues 1149-1190) results in OCs with markedly reduced half-lives.27,31,32 We used the bacteriophage T7-encoded transcription inhibitor gp2, which specifically binds to the β’ jaw domain, as a functional probe to study the contribution of the jaw domain to PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent OC formation on the preopened (-10 to -1) promoter probe. As shown in Fig. 2b (lanes 1-9) and consistent with our previous findings,30 transcription by Eσ54 stimulated by PspF1-275-dATP is resistant to gp2, irrespective of when gp2 is added to the reaction (lanes 4-9). Significantly, in the presence of PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 2b, lanes 12-20), gp2 severely reduced Eσ54 transcription (and hence OC formation) but only when gp2 was added prior to PspF1-275-ATPγS (i.e., before OC formation has occurred) (Fig. 2b, compare lanes 15-17 and 18-20). As expected, control reactions with a gp2-resistant mutant core RNAP (harbouring the E1188K mutation in the β’ jaw domain) showed no sensitivity to gp2 in PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent stimulation of Eσ54 transcription on the supercoiled template (Supplementary Fig. 3). Overall, the use of gp2 as a functional probe of Eσ54 transcription suggests that the slower hydrolysis rates associated with ATPγS are insufficient to trigger conformational changes in the β’ jaw domain frequently enough to permit stable loading of the pre-opened DNA needed for OC formation. Notably, deletion of the β’ jaw domain results in unstable OC formation, and pre-opening the DNA (specifically opening the DNA immediately upstream of the transcription start site) overcomes this phenotype,27 resembling properties of PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent OC formation (see Fig. 1e). We infer that the inefficiency of the PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent stimulation of OC formation on the duplex probe (Fig. 1d) may be due to the inability of the β’ jaw domain to frequently capture (and hence stabilise) melted DNA proximal to the transcription start site. Since regulatory sequences in σ54 Region I that are important for interacting with PspF are also important for cooperativity with the β’ jaw domain for stable OC formation, it seems that conformational coupling between σ54 Region I and the β’ jaw domain may be negatively affected by the slow hydrolysis rate associated with ATPγS.

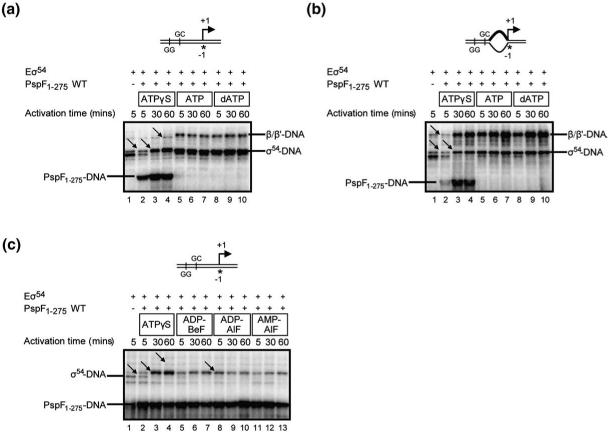

σ54-DNA interactions are altered by PspF1-275-ATPγS

A site-specific protein-DNA cross-linking method was used to study protein-DNA relationship changes for σ54-DNA, β/β’-DNA, and PspF1-275-DNA interactions during PspF1-275-ATPγS-driven OC formation. The photoreactive DNA templates used in this assay were constructed by strategically placing the cross-linking reagent p-azidophenacyl bromide (Sigma) between positions -1 and +1 (-1) in the context of promoter probes 1, 2, and 3 (see below). The -1 site was chosen based on previous results, which revealed that the cross-linking pattern at this position allows a clear differentiation between the CC, an intermediate (ADP-AlF trapped) complex, and the OC, since: (i) only σ54-DNA interactions are detected within the CC; (ii) in the trapped complex, both σ54-DNA and PspF1-275-DNA interactions are present; and (iii) only upon full ATP hydrolysis (i.e., within the OC) are interactions between the β/β’ subunits and the promoter established.15,33

Initially, we analysed by native PAGE a binary σ54-promoter complex formed in the presence of PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM ATPγS, 4 mM ATP, or 4 mM dATP on promoter probe 3 (Fig. 3a, top), which contains an unpaired segment at positions -12 and -11 on the non-template strand, thereby resembling the DNA conformation found within the Eσ54 CC. Previously, we demonstrated that the initial binary σ54-probe 3 complex can be remodelled by PspF1-275-ATP (or dATP) to a “supershift” complex (ssσ54-DNA; Fig. 3a, lanes 5 and 8) that migrates differently in native PAGE analysis but does not contain the activator ATPase PspF1-275; instead, the DNA in this complex is melted (as judged by KMnO4 footprinting) to -5.6,34 Using this assay, we can establish whether early steps in OC formation that rely on σ54 isomerisation can occur in the presence of PspF1-275-ATPγS (and in the absence of the core RNAP). We observed that when PspF1-275 and ATPγS are present, supershift complexes are no longer detected, compared to PspF1-275 and either ATP or dATP (Fig. 3a, compare lanes 2, 5, and 8). Extending the incubation time with PspF1-275-ATPγS failed to result in any detectable accumulation of the isomerised form of σ54 (lanes 3-4). In reactions containing ATP or dATP where supershift complexes were observed in native PAGE analysis (Fig. 3a, lanes 5 and 8, respectively), the cross-linking profile of σ54-DNA in these reactions is altered (Fig. 3b, lanes 5 and 8; the extra band is highlighted with an arrow), compared to σ54 alone (Fig. 3b, lane 1), suggesting that, within the supershift complex, the organisation of σ54 with respect to promoter DNA has changed. These cross-linking data are consistent with the prior observation that, within the supershift complex, no activator protein was present and that σ54 had been remodelled.6 When the supershift complexes were allowed to decay with time (Fig. 3a, compare lane 5 with lanes 6 and 7, and lane 8 with lanes 9 and 10), the cross-linking profile of σ54-DNA in these reactions (Fig. 3b, lanes 6-7 and 9-10) then resembles that of σ54 in the initial binary complex (Fig. 3b, lane 1; a single band is observed). Strikingly, in reactions containing PspF1-275 and ATPγS, we observed an additional cross-linked species that was identified using different molecular weight versions of PspF14 to correspond to PspF1-275-DNA (Fig. 3b, lanes 2-4). Control reactions (Supplementary Fig. 4) lacking σ54 (lane 3), PspF1-275 (lane 1), or ATPγS (lane 2) indicated that σ54, PspF1-275, and ATPγS were all required in the reaction to obtain the cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species (lane 4). Furthermore, we also established that the cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species was also dependent on a form of PspF1-275 that was capable of interacting with σ54 (Supplementary Fig. 4, lanes 6 and 8). Since we are unable to resolve a σ54-DNA-PspF1-275-ATPγS complex by native PAGE, we suggest that the σ54-dependent cross-linked PspF1-275 in the ATPγS reactions probably reflects a relatively unstable interaction between σ54 and PspF1-275, made possible by the slow hydrolysis rate (compared to ATP or dATP) associated with ATPγS. We also note that the cross-linking profile of σ54-DNA has changed in the ATPγS reactions (Fig. 3b, lanes 2-4, marked with an arrow), although the relative amount of promoter bound by σ54 remains similar to that observed for σ54 alone (Fig. 3a, lanes 1-4). The change in the cross-linking profile of σ54-DNA (i.e., the disappearance of the more intense faster-migrating σ54-DNA species present in the σ54-alone reactions) seems to be due to the cross-linkable PspF1-275-DNA species, suggesting that the organisation of σ54 within these reactions is altered. These data indicate that one action of PspF1-275-ATP is to bind to and reorganise σ54 with respect to promoter DNA. Since we observed significantly reduced, if any, cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA in the ATP or dATP reactions, we envisage that fast hydrolysis steps may be required for the ‘release’ of PspF from the σ54-DNA complex.

Fig. 3.

PspF1-275-ATPγS alters the DNA proximities of σ54 and PspF1-275. (a) Nucleotide sequence of the S. meliloti nifH mismatch promoter probe (probe 3) used in this study. Underlined are the two consensus dinucleotide promoter elements GG and GC, which characterise σ54-dependent promoters. Lower-case letters indicate non-complementary residues in probe 3. The symbol used to represent this promoter probe is shown on the right. Native PAGE gel demonstrating that supershift complexes (ssσ54-DNA) are only observed in the presence of PspF1-275 and either ATP or dATP following 5 min incubation time (lanes 5 and 8). The supershift complexes decay (back to the initial σ54-DNA complex) at longer incubation time points (lanes 6-7 and 9-10). The migration positions of the supershift (ssσ54-DNA), initial σ54-DNA (σ54-DNA), and free DNA are as indicated. (b) Denaturing gel showing the cross-linking profiles of σ54-probe 3 complexes in the presence of PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM ATPγS (lanes 2-4), 4 mM ATP (lanes 5-7), or 4 mM dATP (lanes 8-10) following 5 min, 30 min, and 60 min incubation time. The migration positions of the cross-linked σ54-DNA and PspF1-275-DNA species are as indicated.

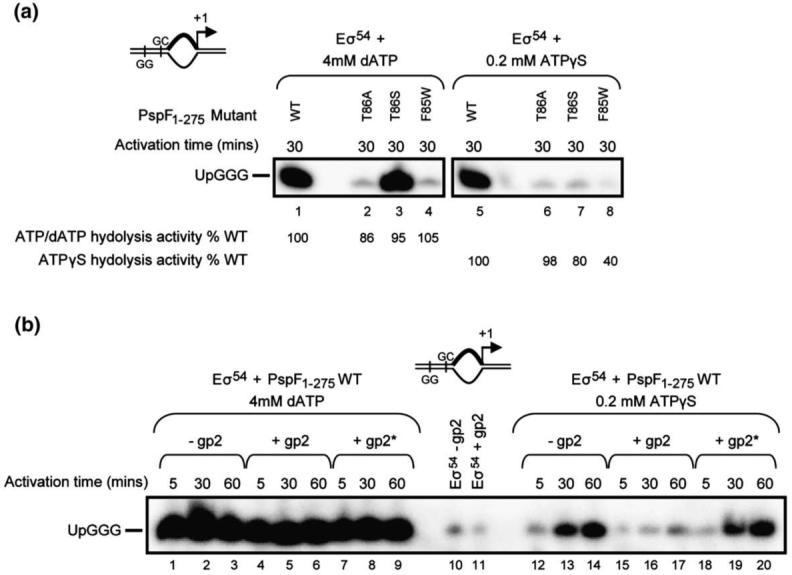

β/β’-DNA interactions follow rearrangements in σ54

Only upon stable OC formation are promoter DNA cross-links with the catalytic β and β’ subunits established, reflecting the loading of DNA within the catalytic cleft of RNAP.15 Since the rate of accumulation of OCs in the presence of PspF1-275-ATPγS is much slower than in the presence of PspF1-275-ATP (or dATP) (Fig. 1c and d), we were able to use the cross-linking assay to monitor β/β’ interactions with the promoter DNA in a time-resolved manner. Importantly, the cross-linking reactions were not competitor-challenged, so that unstable transcription intermediates formed en route to the OC could be captured and analysed. The results shown in Fig. 4a indicate that no interactions with the β/β’ subunits were detected within complexes exposed to PspF1-275-ATPγS even after 60 min incubation time (lanes 2-4), contrasting reactions with ATP (lanes 5-7) or dATP (lanes 8-10). This is consistent with the dramatically reduced transcription activity associated with PspF1-275-ATPγS on promoter probe 1 (Fig. 1d). We note that a very weak band (lane 4, indicated by an arrow) is observed; however, this band is also present in the Eσ54-alone reactions and therefore represents ‘free’ core interacting non-specially with the promoter DNA probe. Furthermore, in the presence of PspF1-275-ATPγS, we note that the profile of the σ54-DNA interactions within Eσ54 complexes has changed from a double band (lane 2, indicated by an arrow) to a single band (lane 3, indicated by an arrow), yet it is not identical to the σ54-DNA species obtained in reactions containing ATP or dATP (e.g., lane 5). Control reactions in which ATPγS is absent show no change in the σ54-DNA cross-linking pattern even after 60 min incubation time (data not shown). This is consistent with our earlier observations (Fig. 3b), suggesting that one primary action of the activator ATPase is to reorganise σ54 (within Eσ54). It would appear that later steps associated with rapid ATP hydrolysis involve the loading of DNA within the catalytic cleft of the RNAP, more specifically engagement of the β’ jaw domain with the promoter DNA to help stabilise OCs (since there was no effect of gp2 on reactions stimulated by either ATP or dATP). We also note that, in line with our earlier observations, PspF1-275-DNA cross-links are detected in Eσ54 reactions containing PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 4a, lanes 2-4), but not in similar reactions containing PspF1-275 and either ATP or dATP (Fig. 4a, lanes 5-10) where OCs efficiently form and prior intermediate complexes containing PspF1-275 have not accumulated.

Fig. 4.

PspF1-275-ATPγS alters the DNA proximities of σ54, PspF1-275, and core (β/β’) RNAP. Denaturing gels showing the cross-linking profiles of Eσ54 promoter complexes formed on (a) probe 1 and (b) probe 2 in the presence of PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM ATPγS (lanes 2-4), 4 mM ATP (lanes 5-7), or 4 mM dATP (lanes 8-10) following 5 min, 30 min, and 60 min incubation time. (c) Denaturing gel showing the cross-linking profile of Eσ54 probe 1 complexes formed in the presence of PspF1-275 and either 0.2 mM ATPγS (lanes 2-4) or the trapping reagents ADP-BeF (lanes 5-7), ADP-AlF (lanes 8-10), or AMP-AlF (lanes 11-13) following 5 min, 30 min, and 60 min of incubation time. In (a)-(c), the migration positions of the cross-linked σ54-DNA, PspF1-275-DNA, and β/β’-DNA species are as indicated.

To determine whether the ATPγS-dependent interaction with PspF1-275 could correspond to an ‘on-pathway’ intermediate, we next analysed these same Eσ54 reactions on the pre-opened promoter since with this probe we were able to detect significantly more abortive products (Fig. 1e). As shown in Fig. 4b, pre-opening the DNA results in the formation of a β/β’ cross-linked species (lanes 3-4) in reactions containing PspF1-275-ATPγS, identical to that observed for PspF1-275 and either ATP or dATP (lanes 5-10). Similar to reactions on the duplex promoter probe (Fig. 4a), a small amount of non-specific ‘free’ core (lane 2, indicated by an arrow) was detected prior to formation of the cross-linked β/β’ species. We also note for the PspF1-275-ATPγS reactions that (i) the σ54-DNA cross-linking profile has changed from a double band (lane 2, indicated by an arrow) to a single band (lane 3, indicated by an arrow), and (ii) cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA is also present (as observed with the linear duplex probe 1; Fig. 4a). Since we observed a similar PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent change in the σ54-DNA relationship on both promoter probes, we propose that one early action of the activator ATPase, potentially with ATP bound in some of its subunits, is to reorganise σ54, an action that precedes changes in the β/β’-DNA relationship. The presence of a cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species only in reactions containing ATPγS (and not ATP or dATP) indicates that the relationship between the activator ATPase and the promoter DNA changes before the change in β/β’-DNA relationship. We observed cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA in reactions containing ATPγS in which transcription levels approach those observed with ATP, consistent with a subset of the Eσ54 population that has not yet formed the transcriptionally proficient OC. Presumably due to its slow hydrolysis rate, ATPγS remains bound by PspF1-275, in association with Eσ54. Pre-opening the DNA, in contrast to reactions using duplex (fully double-stranded) DNA, results in increased numbers of PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent β/β’-DNA cross-linked species (and transcripts; Fig. 1e); one phase of activation in which stable OCs accumulate and melted DNA is loaded into the RNAP is usually linked to relatively rapid ATP hydrolysis used to trigger changes in the location or conformation of the β’ jaw domain required for stable OC formation. With the pre-opened DNA, less frequent changes in the β’ jaw domain, caused by the slow hydrolysis of ATPγS, can be productive.

PspF1-275-ATPγS and its relationship to ATP ground-state and transition-state activator ATPase interactions

Results so far indicate that one action of the activator ATPase interacting with ATPγS is to alter the initial relationship between σ54 and the promoter DNA, and that outcomes from this early event are more apparent after 30 min incubation time (Fig. 4a and b, lane 3, single band with arrow). Interaction with PspF1-275-ATPγS at 5 min of incubation time (Fig. 4a and b, lane 2, double band with arrow, which resembles the σ54-DNA pattern observed in the Eσ54-alone reactions, lane 1) could reflect an initially important—potentially prior to ATP hydrolysis—association of the activator ATPase with the CC. To examine this further, we performed comparative cross-linking assays on the duplex probe (probe 1) with Eσ54, PspF1-275, and either ATPγSor the trapping reagents ADP-BeF, ADP-AlF, and AMP-AlF. It has been proposed that both ADP-BeF10 and AMP-AlF13 reflect ground-state analogues of ATP, whilst ADP-AlF resembles the ATP hydrolysis transition state.9 As shown in Fig. 4c, at 5 min incubation time with PspF1-275-ATPγS, the σ54-DNA cross-linking profile (lane 2, indicated by an arrow) looks similar to the σ54-DNA pattern of the Eσ54-alone reaction (lane 1), but changes to a single band at 30 min incubation time (lane 3, indicated by an arrow). In contrast, each of the trapping reagents tested resulted in a fully altered σ54-DNA profile (lane 8, a single σ54-DNA species indicated by an arrow) after 5 min incubation time with PspF1-275 (lanes 5, 8, and 11). However, the cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species can be detected at all time points, prior to any changes in the σ54-DNA pattern being detected (in reactions with ATPγS, lane 2), implying that interactions between ATP-bound PspF1-275 and σ54 might well occur prior to any ATPγS hydrolysis, although we cannot exclude the possibility that some ATPγS hydrolysis has occurred in some of the subunits even at the 5-min incubation time point.

In order to delineate between ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis, we conducted control reactions using the ATPase defective mutants D107A23,24 (<1% of WT activity) and E108Q23 (1% of WT activity) in the presence of both ATPγS and dATP—our rational being that when an ATP hydrolysis defective mutant is combined with ATPγS, we would be able to significantly restrict ATP hydrolysis (at early time points), enabling access to states associated with ATP binding prior to hydrolysis. Results indicate that in reactions containing E108Q-dATP, a cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species is observed after 5 min incubation time (Supplementary Fig. 5a, lane 8). Interestingly, these conditions permit the formation of a new species with E108Q identified by native PAGE analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5b, lane 9), which migrates similarly to the ADP-AlF trapped complex (data not shown). If the incubation time is increased to 60 min to compensate for the reduced ATP turnover of the mutants, a cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species is now observed in the E108Q-ATPγS reactions (Supplementary Fig. 5a, lane 9, arrow), when no change in the σ54-DNA interactions is observed (double band, lane 9). Importantly, in the E108Q-dATP reactions, after 60 min incubation time, the σ54-DNA relationship is fully altered (lane 10, single band with arrow). Significantly, and consistent with the findings of the in situ trapping reactions (data not shown), no PspF1-275-DNA cross-links or changes in the σ54-DNA profile were obtained with D107A (Supplementary Fig. 5a, lanes 1-5), even though the ATPase activity is similar to E108Q, implying that the integrity of residue D107 may be required for ATP-dependent binding interactions with σ54-DNA, and hence for DNA cross-links with PspF1-275, to be established. Importantly, taken together, these results establish that the cross-link between PspF1-275 and DNA, and the subsequent rearrangement of σ54 with respect to the promoter DNA require conformational changes in some PspF1-275 subunits that occur with ATP binding or after some ATP hydrolysis.

Interestingly, the intensity of the cross-linked σ54-DNA species is different between the PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 4c, lanes 2-4) reactions and the reactions with the trapping reagents (Fig. 4c, lanes 5-13), even though the relative intensity of the cross-linked PspF1-275-DNA species remains constant. These data suggest that the organisation of the activator ATPase (PspF1-275) with respect to DNA within the ATPγS reactions and each of the trapped complexes (ADP-BeF, ADP-AlF, and AMP-AlF) is similar, but the conformation of σ54 in the trapped reactions (Fig. 4c, lanes 5-13) may not necessarily be identical with that found in the ATPγS reactions, especially at early time points (Fig. 4c, lanes 2-4). Since PspF1-275-ATPγS is capable of stimulating OC formation and since ATPγS can be hydrolysed, a more native initial set of interactions between Eσ54 and PspF1-275—distinct from the biochemically stable complexes of the metal-fluoride-dependent trapping reactions—may occur. Such differences may well be attributed to ATPγS giving rise, through its reactivity in yielding ADP, to a mixed nucleotide-bound state, with several different conformations of PspF1-275 subunits existing within one PspF1-275 hexamer.

Discussion

Transcription initiation is a multistep process. For the Eσ54 system, the experimental accessibility of the initial CC has allowed us, with the use of ATPγS, to probe the activation pathway in terms of protein component to DNA proximities in a time-resolved manner. In doing so, we have established that large-scale conformational rearrangements (associated with OC formation) of the catalytic core RNAP subunits β/β’-DNA relationship follow changes in the σ-DNA organisation, and that both rely on nucleotide binding and hydrolysis activities of the activator ATPase (Fig. 4a and b).

Use of ATPγS and ATPγS hydrolysis

The PspF1-275-dependent formation of ADP from ATPγS was much slower than the formation of ADP from ATP, but ATPγS hydrolysis could be coupled to the large-scale productive conformational changes in Eσ54 required for OC formation. We infer that ATPγS binding to PspF1-275, catalysed cleavage to yield ADP and thiophosphate, and ADP and thiophosphate product release steps support the same mechanism of large-scale protein conformational changes that leads to NTP hydrolysis-dependent OC formation when ATP is supplied. In the absence of a detailed kinetic analysis of the steps involved in the enzymatic cleavage of γ-thiophosphate from ATPγS, we can not say precisely which steps occurring in PspF1-275 are rate-limiting for OC formation, although steps leading to the successful nucleophilic attack of the γ-β bond, rather than bond scission per se, may be slowed considerably. For example, the precise positioning of protein (PspF1-275) structure around ATPγS, to form the active site, may be slower than with ATP, and activation of the attacking water molecule or positioning of the R-finger needed to stabilise the transition state may be somewhat disfavoured by a non-native γ-β phosphate bond. Furthermore, the ease with which the modified γ-β phosphate bond in ATPγS can be activated for scission may differ from the γ-β phosphate bond in ATP and thus change the probability of populating the transition state for hydrolysis.

Initial complexes and early phase of activation

In the presence of ATPγS, we detected an unstable (compared to the trapped complexes) σ54-DNA-PspF1-275-ATPγS complex. Given the slow rate of hydrolysis associated with ATPγS, we assume that PspF1-275 in such complexes is predominantly bound by ATPγS. Utilisation of an ATPγS-bound form of PspF1-275 (Figs. 3b and 4a and b) and mutant forms of PspF1-275 with very low ATPase activity (Supplementary Fig. 5a) suggests that a productive (in terms of OC formation) interaction between σ54 and PspF1-275 occurs prior to, or after a small amount of, ATP hydrolysis. With PspF1-275-ATPγS, changes in the σ54-DNA cross-linking profile were detected when no cross-links were observed with the β/β’ subunits (Fig. 4a), suggesting that activator ATPase-dependent alterations occurring in the σ54 factor precede changes in RNAP organisation. Since close-proximity relationships between the β/β’ subunits and DNA were not observed at early incubation times (Fig. 4b, lane 2), we propose that the conformational changes in RNAP organisation occur after any further ATP has been hydrolysed. Although the stabilities of σ54-PspF1-275 and Eσ54-PspF1-275 complexes formed in the presence of ATPγS are different compared to ADP-AlF, they clearly share an ability to interact with σ54 (Fig. 4c). Therefore, the organisation of the σ54-interacting Loop 1 of PspF is, in structural terms, favourably equilibrated with the nucleotide binding pocket when ATP is bound, and not just at the transition state (Fig. 4c), since it would be difficult to envisage how the protein structure would equilibrate at the transition state, as the transition state is so shortlived. The cross-linking data with PspF1-275 and ATPγS (Figs. 3b and 4a-c) and the ground-state analogue ADP-BeF (Fig. 4c) suggest that, upon ATP binding, the engagement of Loop 1 with σ54 is retained up to and throughout the life of the ATP transition state (mimicked with ADP-AlF) (Fig. 4c).

Time-dependent σ54-DNA cross-links within Eσ54

Changes in the σ54-DNA cross-linking profile (from a double band to a single band) within Eσ54 complexes were observed at position -1 in the DNA in response to an interaction with PspF1-275-ATPγS. However, these PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent changes in the σ54-DNA cross-linking profile are less apparent at early (5 min) time points (Fig. 4a and b, lane 2). It appears that conversion of the CC to the OC is dominated by two distinct conformational states of σ54-DNA (evident as two σ54-DNA bands in the cross-linking assay), where the slower migrating species becomes more intense in a NTP-hydrolysis-dependent and time-dependent manner. It seems likely that some change in the σ54-DNA organisation takes place after the initial interaction between σ54-DNA and PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 4a and b, lane 2), and that further changes occur either upon ATPγS hydrolysis or as PspF1-275 positions ATPγS, ready for hydrolysis to occur, thereby adopting a new conformation (Fig. 4a, lane 3). Results with PspF1-275 E108Q are in agreement with either proposition (Supplementary Fig. 5a). If the σ54-DNA-PspF1-275-ATPγS state persists without hydrolysis, some reorganisation of the CC may represent the outcomes of an ‘on’ enzyme equilibrium between activator ATPase and σ54-DNA rather than a hydrolysis-dependent set of changes. Similarities between the σ54-DNA and PspF1-275-DNA cross-linked species in the presence of ATPγS and ADP-BeF (Fig. 4c) suggest that hydrolysis-independent σ54-DNA reorganisations can occur with ATP in its ground state.

Accumulation of β/β’-DNA cross-links

Cross-links between the catalytic β/β’ subunits and promoter DNA position -1 were both time-dependent and DNA structure-dependent (Fig. 4a and b). With the use of either ATPγS (Fig. 4a and b) or the PspF1-275 E108Q mutant (Supplementary Fig. 5a) to slow the transition from the CC to the OC, the cross-links between β/β’ and the promoter DNA accumulated after changes in the σ54-DNA cross-linking profile had been detected, suggesting that reorganisation of the catalytic β/β’ subunits follows reorganisation of the σ54-DNA relationship. This is consistent with the observation that the interaction between σ54 and core RNAP is altered following ATP hydrolysis-dependent isomerisation of σ54.34 Recovery of β/β’ cross-links when using the preopened (-10 to -1) probe in reactions containing PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 4b, lanes 3 and 4) and inhibition of transcription by gp2 (Fig. 2b, lanes 15-17) suggest that rapid ATP hydrolysis favours formation of the OC, and that slow hydrolysis of ATPγS populates unstable competitor (heparin)-sensitive intermediates that rarely convert into stable OCs. Rapid conformational coupling within promoter complexes may be required for stable OC formation and may rely on concerted changes in σ54 and structurally flexible features of the catalytic β and β’ subunits, including the β’ jaw domain. The proximity of σ54 to the -1 DNA position in the cross-linking experiments may reflect the existence of a microdomain bounded somewhere between -12 and -1 within the CC that is potentially used for DNA melting, somewhat analogous to the situation in Eσ70, where a subdomain comprising less than one-fifth of Eσ70 is sufficient for DNA melting.35 Recent structural studies of PspF1-275-bound Eσ54 suggest that such a microdomain would come into play (for DNA melting) after ADP and Pi have been formed by the activator.36

Time-dependent PspF1-275-DNA cross-links

In the presence of σ54 and ATPγS(Figs. 3b and 4a and b, lanes 2-4), but not ATP (Figs. 3b and 4a and b, lanes 5-7) or dATP (Figs. 3b and 4a and b, lanes 8-10), PspF1-275 can be cross-linked to DNA, indicating that, prior to the occurrence of DNA proximity changes with the β/β’ subunits, the proximity relationship between PspF1-275 and DNA is distinct. The subsequent loss of cross-links to PspF1-275 correlates with the reorganisation of RNAP being evident and suggests that PspF1-275 is not engaged within the RNAP promoter complex once cross-links characteristic of the OC are detected. Hence we propose that activator ATPase release from Eσ54 occurs upon, or just prior to, completion of stable OC formation. Failure to see PspF1-275-DNA cross-links when using dATP or ATP can be attributed to their rapid (compared to ATPγS) turnover and hence only transient support of an association between PspF1-275 and the CC.

Pathways for making OCs

In several respects, activation by PspF1-275-ATPγS resembles certain activator bypass forms of σ54, which fail to effectively form stable OCs and can not initiate transcription from duplex linear DNA templates, but can do so from supercoiled or pre-opened DNA.37,38 We suggest that the promoter and core RNAP interactions made by an activator bypass form of σ54 and the reorganisation of wild-type σ54 evident when using PspF1-275-ATPγS (Fig. 4a and b, lanes 2-4) or PspF1-275 E108Q-dATP (Supplementary Fig. 5a) are functionally related to early events in transcription activation. Changes in the binding interactions between RNAP and σ54, as altered by the activator ATPase, link the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to reorganisation of the RNAP to accommodate the DNA within the catalytic cleft of RNAP. Importantly, inhibition of PspF1-275-ATPγS-dependent transcription activation in the presence of gp2 (Fig. 2b, lanes 15-17) and its relative resistance when PspF1-275 and either ATP (data not shown) or dATP (Fig. 2b, lanes 4-9) are used strongly support this view. One possibility is that DNA contacts by core RNAP associated with the opening of double-stranded DNA might not efficiently, or frequently enough, form in PspF1-275-ATPγS-driven activation reactions to capture transiently opened DNA, but that sufficient change in the accessibility of the downstream channel of RNAP does occur to allow effective utilisation of pre-opened DNA. Although our experiments with ATPγS do not reveal where (in terms of inside or outside of the RNAP catalytic cleft) DNA melting occurs, the results imply that, for Eσ54, DNA melting outside of the catalytic cleft is not disallowed.39

Overall, our data provide clear evidence for a coupling of activator ATPase-driven changes in the organisation of σ54-DNA to changes in RNAP conformation used for OC formation, and uncover a kinetic barrier to gene expression. Importantly, we also demonstrate how ATPγS can be utilised as a tool for studying the activities of other ATPases, in particular the initial interactions that the ATP-bound form of the ATPase makes with its substrate, as well as the formation of the final products of the ATP hydrolysis event.

Materials and Methods

Proteins and DNA probes

E. coli core RNAP was purchased from Epicentre Technology (Cambio). Klebsiella pneumoniae σ54 and E. coli PspF1-275 were purified as described previously.28 The S. meliloti nifH phosphorothioated (Operon) DNA probes were derivatised with p-azidophenacyl bromide at the -1/+1 position, as described previously.14,15 The (modified) promoter strands were 32P-labelled and annealed to the complementary strand, as described previously.15,28

ADP-AlF trapping experiments

ADP-AlF trapping experiments were performed in STA buffer [25 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.0), 8 mM Mg-acetate, 10 mM KCl, and 3.5% wt/vol polyethylene glycol 6000] in a10 μl volume containing 5 μM PspF1-275, 1 μM σ54, and 5 mM NaF. This mix was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, and then 0.2 mM ATPγS or 0.2 mM ATP was added, and the reaction was incubated for the specified times. The “trapping” reactions were initiated upon addition of 0.4 mM AlCl3 and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. The samples were analysed using a 4.5% nondenaturing gel run at 100 V for 55 min. Proteins were detected by Coomassie blue staining and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 densitometer.

In vitro full-length or abortive transcription assays

Full-length or abortive transcription assays were performed in STA buffer in a 10 μl reaction volume containing 100 nM Eσ54 (reconstituted using a 1:4 ratio of E:σ54) and either dATP, ATP, or ATPγS (at the specified concentration) and 20 nM promoter DNA probe. The mix was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and the reaction was started by the addition of 5 μM PspF1-275 (or PspF1-275 mutants, where indicated) and incubated for the indicated time at 37 °C. Full-length transcription was initiated by adding a mix containing 100 μg/ml heparin; 1 mM ATP, cytidine triphosphate, and guanosine triphosphate; 0.05 mM UTP; and 3 μCi of [α-32P]UTP for a further 20 min. The reaction was quenched by addition of loading buffer and analysed on a 6% sequencing gel. The synthesis of abortive transcript (UpGGG) was initiated by adding a mix containing 100 μg/ml heparin, 0.5 mM UpG, and 4 μCi [α-32P]guanosine triphosphate for a further 20 min. Where indicated, gp2 was present in a fivefold molar excess over Eσ54. In +gp2 reactions, gp2 was added prior to PspF1-275 (to holoenzyme assemblies); in +gp2* reactions, gp2 was added after PspF1-275 (to the OC). The reaction was quenched by addition of loading buffer and analysed on a 20% denaturing gel. Full-length transcription gels were dried, and transcripts were visualised and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 PhosphorImager.

ATPase activity

ATPase activity assays were performed using the ATPase colourimetric assay kit Pi Colorlock Gold (Innova Biosciences, UK). The reaction mix containing 35 mM Tri-acetate (pH 8.0), 70 mM K-acetate, 15 mM Mg-acetate, 19 mM NH4-acetate, 0.7 mM DTT, and varying concentrations of PspF1-275 was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, and the colour reaction was started by adding 1 mM ATP or 0.1 mM ATPγS. Reactions were stopped by addition of kit reactant, and phosphate release was measured.

Photo cross-linking assays

Photo cross-linking reactions were conducted at 37 °C in STA buffer in a total reaction volume of 10 μl, as previously described.15 Briefly, where indicated, either 1 μM σ54 or 200 nM Eσ54 holoenzyme (reconstituted using a 1:2 ratio of E:σ54), 0.2 mM ATPγS, 4 mM ATP or dATP, and 20 nM modified 32P-labelled promoter DNA probe were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. PspF1-275 (5 μM) was then added to the reactions and incubated for either 5 min, 30 min, or 60 min at 37 °C. Trapped complexes were formed in situ by adding 5 μM PspF1-275, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM ADP, and 0.2 mM BeCl3 for the ADP-BeF reactions; 1 mM ADP and 0.2 mM AlCl3 for the ADP-AlF reactions; and 1 mM AMP and 0.2 mM AlCl3 for the AMP-AlF reactions, and incubated for either 5 min, 30 min, or 60 min at 37 °C. To eliminate free core RNAP binding the promoter probe, all reactions contained 100 ng/μl salmon sperm DNA. Reactions were UV-irradiated at 365 nm for 30 s using a UV-Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene). A 2 μl sample of the cross-linking reaction was analysed by native PAGE (4.5%) gel run at 100 V for 55 min. The rest of the cross-linking reaction was diluted by addition of 5 μl of 10 M urea and 5 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer (Sigma). The samples were heated at 95 °C for 3 min, and 10 μl was loaded onto a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel run at 200 V for 50 min. The gels were dried, and cross-linked protein-DNA complexes were visualised and quantified using a FLA-5000 PhosphorImager. The cross-linked proteins were identified using antibodies, as described previously.15

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants to M.B. and X.Z. from the Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), and by a grant to B.T.N. from the National Institutes of Health (GM069937). S.R.W. is a recipient of a BBSRC David Phillips Fellowship (BB/E023703/1), N.J. is a recipient of an EMBO Fellowship (ALTF 387-2005), and K.D. is a recipient of a BBSRC postgraduate studentship. We thank Mr. C. Engl, Dr. G. Jovanovic, and Dr. J. Schumacher for valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank the members of the Buck and Nixon laboratories for helpful discussions and support.

Abbreviations used

- RNAP

RNA polymerase

- CC

closed complex

- OC

open complex

- PspF

phage shock protein F

- gp2

gene protein 2

- NTP

nucleoside triphosphate

- BBSRC

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Cramer P. Multisubunit RNA polymerases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rappas M, Bose D, Zhang X. Bacterial enhancer-binding proteins: unlocking sigma54-dependent gene transcription. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schumacher J, Joly N, Rappas M, Zhang X, Buck M. Structures and organisation of AAA+ enhancer binding proteins in transcriptional activation. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;156:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TK, Ebright RH, Reinberg D. Mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter melting by transcription factor IIH. Science. 2000;288:1418–1422. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin YC, Choi WS, Gralla JD. TFIIH XPB mutants suggest a unified bacterial-like mechanism for promoter opening but not escape. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nsmb949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon WV, Gallegos MT, Buck M. Isomerization of a binary sigma-promoter DNA complex by transcription activators. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:594–601. doi: 10.1038/76830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo Y, Lew CM, Gralla JD. Promoter opening by sigma(54) and sigma(70) RNA polymerases: sigma factor-directed alterations in the mechanism and tightness of control. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2242–2255. doi: 10.1101/gad.794800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wigneshweraraj S, Bose D, Burrows PC, Joly N, Schumacher J, Rappas M, et al. Modus operandi of the bacterial RNA polymerase containing the sigma54 promoter-specificity factor. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:538–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaney M, Grande R, Wigneshweraraj SR, Cannon W, Casaz P, Gallegos MT, et al. Binding of transcriptional activators to sigma 54 in the presence of the transition state analog ADP-aluminum fluoride: insights into activator mechanochemical action. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2282–2294. doi: 10.1101/gad.205501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen B, Doucleff M, Wemmer DE, De Carlo S, Huang HH, Nogales E, et al. ATP ground- and transition states of bacterial enhancer binding AAA+ ATPases support complex formation with their target protein, sigma54. Structure. 2007;15:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, De La Torre A, Yan D, Kustu S, Nixon BT, Wemmer DE. Regulation of the transcriptional activator NtrC1: structural studies of the regulatory and AAA+ ATPase domains. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2552–2563. doi: 10.1101/gad.1125603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rappas M, Schumacher J, Beuron F, Niwa H, Bordes P, Wigneshweraraj S, et al. Structural insights into the activity of enhancer-binding proteins. Science. 2005;307:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joly N, Rappas M, Buck M, Zhang X. Trapping of a transcription complex using a new nucleotide analogue: AMP aluminium fluoride. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:1206–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burrows PC, Severinov K, Buck M, Wigneshweraraj SR. Reorganisation of an RNA polymerase-promoter DNA complex for DNA melting. EMBO J. 2004;23:4253–4263. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burrows PC, Wigneshweraraj SR, Buck M. Protein-DNA interactions that govern AAA+ activator-dependent bacterial transcription initiation. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer AN, Barany F. Photoaffinity cross-linking of TaqI restriction endonuclease using an aryl azide linked to the phosphate backbone. Gene. 1995;153:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00752-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wedel A, Kustu S. The bacterial enhancer-binding protein NTRC is a molecular machine: ATP hydrolysis is coupled to transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2042–2052. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.16.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popham DL, Szeto D, Keener J, Kustu S. Function of a bacterial activator protein that binds to transcriptional enhancers. Science. 1989;243:629–635. doi: 10.1126/science.2563595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Protein unfolding by a AAA+ protease is dependent on ATP-hydrolysis rates and substrate energy landscapes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:139–145. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauna ZE, Kim IW, Nandigama K, Kopp S, Chiba P, Ambudkar SV. Catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis by P-glycoprotein: evidence for formation of the ES reaction intermediate with ATP-gamma-S, a nonhydrolyzable analogue of ATP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13787–13799. doi: 10.1021/bi701385t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bordes P, Wigneshweraraj SR, Schumacher J, Zhang X, Chaney M, Buck M. The ATP hydrolyzing transcription activator phage shock protein F of Escherichia coli: identifying a surface that binds sigma 54. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2278–2283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537525100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rappas M, Schumacher J, Niwa H, Buck M, Zhang X. Structural basis of the nucleotide driven conformational changes in the AAA+ domain of transcription activator PspF. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joly N, Rappas M, Wigneshweraraj SR, Zhang X, Buck M. Coupling nucleotide hydrolysis to transcription activation performance in a bacterial enhancer binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:583–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacher J, Zhang X, Jones S, Bordes P, Buck M. ATP-dependent transcriptional activation by bacterial PspF AAA+ protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:863–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joly N, Schumacher J, Buck M. Heterogeneous nucleotide occupancy stimulates functionality of phage shock protein F, an AAA+ transcriptional activator. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34997–35007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher J, Joly N, Claeys-Bouuaert IL, Aziz SA, Rappas M, Zhang X, Buck M. Mechanism of homotropic control to coordinate hydrolysis in a hexameric AAA+ ring ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wigneshweraraj SR, Burrows PC, Severinov K, Buck M. Stable DNA opening within open promoter complexes is mediated by the RNA polymerase beta’-jaw domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:36176–36184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wigneshweraraj SR, Nechaev S, Bordes P, Jones S, Cannon W, Severinov K, Buck M. Enhancer-dependent transcription by bacterial RNA polymerase: the beta subunit downstream lobe is used by sigma 54 during open promoter complex formation. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:646–657. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon W, Gallegos MT, Casaz P, Buck M. Amino-terminal sequences of sigmaN (sigma54) inhibit RNA polymerase isomerization. Genes Dev. 1999;13:357–370. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wigneshweraraj SR, Burrows PC, Nechaev S, Zenkin N, Severinov K, Buck M. Regulated communication between the upstream face of RNA polymerase and the beta’ subunit jaw domain. EMBO J. 2004;23:4264–4274. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ederth J, Artsimovitch I, Isaksson LA, Landick R. The downstream DNA jaw of bacterial RNA polymerase facilitates both transcriptional initiation and pausing. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:37456–37463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wigneshweraraj SR, Savalia D, Severinov K, Buck M. Interplay between the beta’ clamp and the beta’ jaw domains during DNA opening by the bacterial RNA polymerase at sigma54-dependent promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:1182–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joly N, Burrows PC, Buck M. An intramolecular route for coupling ATPase activity in AAA+ proteins for transcription activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:13725–13735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cannon W, Gallegos MT, Buck M. DNA melting within a binary sigma(54)-promoter DNA complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:386–394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young BA, Gruber TM, Gross CA. Minimal machinery of RNA polymerase holoenzyme sufficient for promoter melting. Science. 2004;303:1382–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1092462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bose D, Pape T, Burrows PC, Rappas M, Wigneshweraraj SR, Buck M, Zhang X. Organization of an activator-bound RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang JT, Syed A, Gralla JD. Multiple pathways to bypass the enhancer requirement of sigma 54 RNA polymerase: roles for DNA and protein determinants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9538–9543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JT, Syed A, Hsieh M, Gralla JD. Converting Escherichia coli RNA polymerase into an enhancer-responsive enzyme: role of an NH2-terminal leucine patch in sigma 54. Science. 1995;270:992–994. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim HM, Lee HJ, Roy S, Adhya S. A “master” in base unpairing during isomerization of a promoter upon RNA polymerase binding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14849–14852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261517398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.