Abstract

It is widely accepted that reactive oxygen species (ROS) promote tumorigenesis. However, the exact mechanisms are still unclear. As mice lacking the peroxidase peroxiredoxin1 (Prdx1) produce more cellular ROS and die prematurely of cancer, they offer an ideal model system to study ROS-induced tumorigenesis. Prdx1 ablation increased the susceptibility to Ras-induced breast cancer. We, therefore, investigated the role of Prdx1 in regulating oncogenic Ras effector pathways. We found Akt hyperactive in fibroblasts and mammary epithelial cells lacking Prdx1. Investigating the nature of such elevated Akt activation established a novel role for Prdx1 as a safeguard for the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN, which is essential for its tumour suppressive function. We found binding of the peroxidase Prdx1 to PTEN essential for protecting PTEN from oxidation-induced inactivation. Along those lines, Prdx1 tumour suppression of Ras- or ErbB-2-induced transformation was mediated mainly via PTEN.

Keywords: oxidative stress, peroxiredoxin1, PTEN phosphatase, transformation, tumour initiation

Introduction

Peroxiredoxins (Prdxs) are a superfamily of small non-seleno peroxidases (22–27 kDa) currently known to possess six mammalian isoforms. Although their individual roles in cellular redox regulation and antioxidant protection are quite distinct, they all catalyse peroxide reduction to balance cellular H2O2 levels essential for signalling and metabolism (Rhee, 2006). Prdxs I–IV share the common CxxC motif and use thioredoxin (Trx) as an electron donor (Chae et al, 1994a). On reaction with peroxides, the Prdxs' ‘peroxidatic' cysteine (Cys51 in Prdx1) is oxidized into a sulfenic acid intermediate, which then forms a disulfide bond with the ‘resolving' cysteine (Cys172 in Prdx1) from the other homodimer's subunit. Catalytic reduction of peroxides results in different oxidation states of the catalytic cysteine. Lower oxidation states (sulfenic acid) are reduced back to thiol by the Trx system. Higher oxidation states such as sulfinic acid can be reduced back to thiol by sulfiredoxin, whereas the oxidation to sulfonic acid is irreversible and results in Prdx degradation (Neumann and Fang, 2007). Loss of Prdx1 shortens the life span of mice due to the development of hemolytic anemia and cancer. Analysis of cells and mice lacking Prdx1 suggested that it not only regulated H2O2 levels, but also that it possessed the properties of a tumour suppressor (Neumann et al, 2003), which was further supported by the finding that Prdx1 interacts with c-Myc thereby selectively inhibiting c-Myc transcriptional activity (Egler et al, 2005).

Peroxides are known to modify protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) by oxidation. PTP catalytic property depends on a thiolate anion of a low pKa cysteine residue (pKa 4.7–5.4) located in the conserved motif of its active site (Zhang and Dixon, 1993; Peters et al, 1998). This highly nucleophilic group makes the initial attack on the phosphate group of the substrate, but renders the PTP extremely susceptible to oxidation resulting in its inactivation. The PTP and tumour suppressor PTEN exhibits phosphatase activity towards phosphoinositides and tyrosine phosphates and is known to be inactivated through H2O2-mediated oxidation or through growth factor signalling, including epithelial growth factor (EGF) or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (Leslie et al, 2003; Kwon et al, 2004). Analysis of human recombinant PTEN revealed that two of the five cysteines in its N-terminal phosphatase domain (PTD) (Cys71 and Cys124) form a disulfide bond after oxidation, which resulted in the transient inhibition of its phosphatase activity and allowed oxidized PTEN to migrate faster on a non-reducing SDS–PAGE (Lee et al, 2002; Kwon et al, 2004). In stimulated macrophages, PTEN oxidation led to the temporary inhibition of its phosphatase activity and in the phosphorylation of Akt on Serine 473 (Leslie et al, 2003).

PTEN deficiency is a hallmark of many human tumours (Keniry and Parsons, 2008) and is accompanied by enhanced cell proliferation, decreased cell apoptosis and increased Akt activity (Stambolic et al, 1998). Akt is regulated by PI3K and PTEN, thus playing a central role particularly in Ras- and ErbB-2-induced transformation. Akt activity has been proven crucial for the initiation of this transformation, both in vitro and in vivo (Sheng et al, 2001; Hutchinson et al, 2004; Lim and Counter, 2005) and phosphatase inactive PTEN (PTEN Cys124Ser) is incapable of suppressing Ras-induced transformation either in vitro or in vivo (Tolkacheva and Chan, 2000; Koul et al, 2002).

Although it is known that PTEN activity is negatively regulated through oxidation, the existence of a protective mechanism inhibiting such inactivation has not been proposed. On the basis of our findings, we propose here that Prdx1 promotes PTEN tumour suppressive function by binding PTEN and protecting its lipid phosphatase activity from H2O2-induced inactivation. This way, Prdx1 controls excessive cellular Akt activity and reduces the susceptibility to H-Ras and ErbB-2-induced transformation.

Results

Prdx1 inhibits Ras-induced transformation through its peroxidase activity

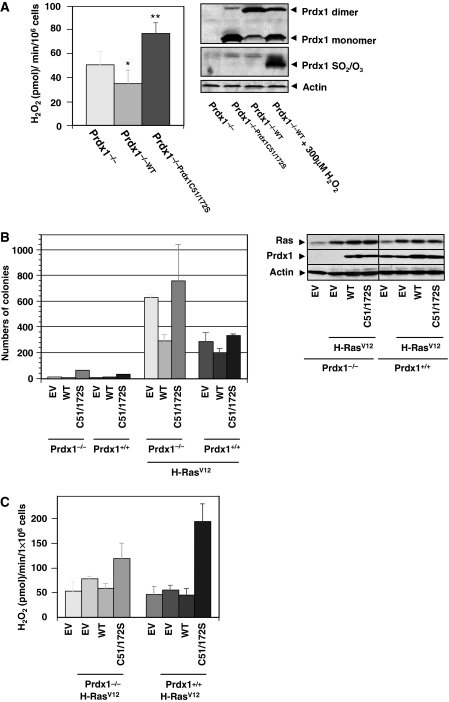

We tested first Prdx1 peroxidase activity under physiological conditions and measured endogenous H2O2 release in growing cells over time. Extracellular H2O2 buildup from Prdx1−/−;Prdx1WTMEFs was less compared with Prdx1−/−MEFs during the 240 min measured. In contrast, Prdx1−/−;Prdx1C51/172SMEFs resulted in an excess of extracellular H2O2 buildup (Supplementary Figure S1A). Rates calculated for extracellular H2O2 buildup (pmol/min) confirmed that Prdx1−/−;Prdx1WTMEFs released H2O2 at a 30% lower rate than Prdx1−/−MEFs, whereas Prdx1−/−;Cys51/172SMEFs released H2O2-release 1.5-fold more than Prdx1−/−MEFs (Figure 1A, left panel). Western blotting analysis further confirmed that Prdx1 was functioning as a peroxidase, as Prdx1WT protein formed mostly DTT-reducible (data not shown) H2O2-scavenging dimeric structures (Figure 1A, right panel), whereas Prdx1Cys51/172S did not, as dimer formation depends on Cys51 and Cys172 disulfides (Chae et al, 1994b). The remaining Prdx1 monomers were not over-oxidized and therefore active (unlike Prdx1 monomers in H2O2-treated Prdx1−/−;Prdx1WTMEFs). Prdx1 peroxidase activity was required to suppress H-Ras-induced tumour suppression, as Prdx1−/−MEFs transduced with retrovirus expressing H-RasV12 formed two-fold more colonies in soft agar compared with Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs (Figure 1B, left panel). Expression of exogenous Prdx1WT reduced colony formation by 50% in Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs and by 20% in Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs, whereas exogenously expressed Prdx1C51/172S modestly increased colony formation in Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs and Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs. Western blot analysis ensured that re-expression of Prdx1 proteins in Prdx1−/−MEFs did not exceed those Prdx1 levels found in Prdx1+/+MEFs (Figure 1B, right panel). Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs appeared also more spindle-like than Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs, whereas expression of Prdx1WT in Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs reversed the spindle-like morphology. Expression of exogenous Prdx1C51/172S, however, promoted spindle-like cell morphology in both Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs and Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs (Supplementary Figure S1B). Analysis of the Prdx1 peroxidase activity in H-RasV12-transformed MEFs showed that Prdx1−/−;Prdx1WT;H−RasV12MEFs released H2O2 at a 26% lesser rate than Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs, which was comparable to the rate found Prdx1−/−EVMEFs. In contrast, Prdx1−/−;C51/172S;H−RasV12MEFs had a 1.5-fold increased rate of H2O2 release compared with Prdx1−/−;Prdx1WT;H−RasV12MEFs (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Left panel: rate of H2O2 release per minute was analysed by calculating the linear slope of data obtained in Supplementary Figure S1A. H2O2 release is expressed per 1 × 106 cells per minute. P-values were calculated using an unpaired Student's t-test. Rate of H2O2 release in Prdx1−/−MEFs compared with either Prdx1−/−Prdx1WTMEFs (*P=0.04) or Prdx1−/−Prdx1Cys51/172S (**P=0.001). Right panel: protein levels and oxidation status of expressed Prdx1 in MEFs used in left panel. Protein lysates were prepared as described under Materials and methods and analysed under non-reducing conditions. Status of over-oxidized Prdx1 was tested by using an antibody recognizing Prdx1 (Prdx1-SO2/SO3) (Woo et al, 2003). (B) Left panel: Prdx1−/−MEFs and Prdx1+/+MEFs were infected with retroviral constructs carrying genes for Prdx1WT or Prdx1C51/172S. MEFs were further infected with retrovirus expressing either H-RasV12 or puromycin resistance gene only (EV) and plated in duplicates in soft agar. Colonies were counted after 18–20 days. Right panel: proteins of clones used in soft agar experiment were analysed for expression levels of Prdx1 and Ras. (C) Rate of H2O2 release per minute was analysed by calculating the linear slope of MEFs used in (B, left panel). For each clone, six wells were plated and analysed. The experiment shown here is representative of three independent studies from two different sets of MEF clones obtained from Prdx1 littermates. P-values were calculated using an unpaired Student's t-test. *P=0.045; **P=0.004. Differences in Prdx1+/+MEFs were not statistically significant.

Loss of Prdx1 promotes PTEN oxidation and Akt activation

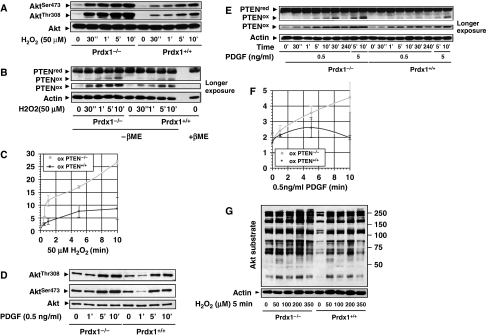

We investigated now whether Prdx1 regulates H-Ras effector pathways known to promote transformation, including PI3K/Akt, RalGEF or MAPK pathways (Li et al, 2004; Lim and Counter, 2005). Treatment of MEFs with H2O2 (50 μM) for increasing periods of time enhanced Akt phosphorylation on Ser473 (pAktSer473) and Thr308 (pAktThr308) at a higher level in Prdx1−/−MEFs compared with Prdx1+/+MEFs (Figure 2A). This finding correlated with a steady increase of PTEN oxidation over time in Prdx1−/−MEFs, whereas in Prdx1+/+MEFs PTEN oxidation plateaued after 6–8 min (Figure 2B and C). Phosphorylation of Akt on serine 473 (pAktSer473) and PTEN oxidation increased also in Prdx1−/− MEFs compared with Prdx1+/+MEFs when exposed to increasing amounts of H2O2 (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). Similar data were obtained by inducing H2O2 endogenously through treating cells with PDGF, as it led to a larger increase in (1) pAktSer473 and pAktThr308 (Figure 2D) and (2) PTEN oxidation in Prdx1−/−MEFs when compared with Prdx1+/+MEFs (Figure 2E). Although PTEN oxidation steadily increased in Prdx1−/−MEFs, it decreased in Prdx1+/+MEFs over time (Figure 2E and F). Levels of PAktSer473 and PTEN oxidation was also increased in Prdx1−/−MEFs compared with Prdx1+/+MEFs when exposed to increasing amounts of H2O2 or PDGF (Supplementary Figure S2A–D). Lastly, we confirmed that lack of Prdx1 enhanced basal and H2O2-induced phosphorylation of Akt substrates in Prdx1−/−MEFs more than in Prdx1+/+MEFs (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

(A) Prdx1−/−MEFs and Prdx1+/+MEFs were stimulated with H2O2 as indicated. Protein lysates were collected under argonized conditions by scraping cells into argon-purged lysis buffer (see Materials and methods) and analysed under non-reducing conditions on SDS–PAGE. Akt phosphorylation was detected on Ser473 and Thr308. Akt protein as loading control. (B) Prdx1−/−MEFs and Prdx1+/+MEFs protein lysates were treated as described under (A) and analysed for oxidized PTEN proteins. Actin as loading control. (C) Levels of oxidized PTEN proteins were evaluated by quantifying oxidized and reduced PTEN using a Fuji imaging system (LAS 3000) and related software (ImageGuage). Quantifications of staining intensities were obtained by analysing protein bands from the same ECL obtained film exposure. The y-axis represents staining intensities in arbitrary units of oxidized PTEN. Curves represent data from three independent experiments. (D) Prdx1−/−MEFs and Prdx1+/+MEFs were stimulated with PDGF as indicated. Protein lysates were collected and analysed as described under (A). (E) Prdx1−/−MEFs and Prdx1+/+MEFs protein lysates were treated as described under (D) and analysed for oxidized PTEN proteins. Actin as loading control. (F) Data analysis was done as described under (C). All experiments shown are representative of at least three independent studies including two sets of MEF clones from Prdx1 littermates. (G) Serum starved MEFs were stimulated with H2O2 as indicated. Protein lysates were collected and analysed as described under (A). Akt substrates were detected by western blotting using an phospho-Akt substrate antibody (RXRXXS/T).

Prdx1 interacts with PTEN

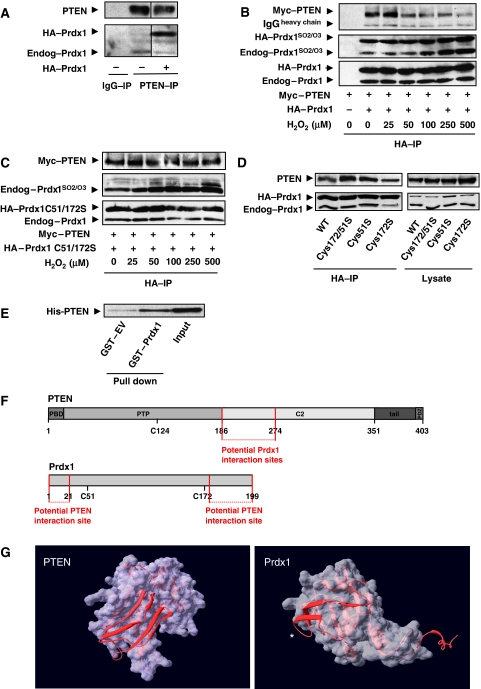

PTEN forms a complex with endogenous and epitope-tagged HA–Prdx1 (Figure 3A). This complex was regulated by oxidative stress, as co-expressed epitope-tagged Myc–PTEN and HA–Prdx1 dissociated under increasing concentrations of oxidative stress (Figure 3B, upper panel). In contrast, increasing dosages of H2O2 did not disrupt binding of Prdx1Cys51/72Ser with PTEN (Figure 3C). Immunoblotting confirmed equal expression of proteins (Supplementary Figure S3A and B). Peroxidatic Cys51 may regulate the H2O2-induced Prdx1:PTEN complex disruption as Prdx1C51S and Prdx1C51/172S proteins bind more to wild-type PTEN than Prdx1C172S (Figure 3D). We further confirmed a physical association between Prdx1 and PTEN by using GST-pull down of GST–Prdx1 and His–PTEN (Figure 3E). Mutational analysis suggested that Prdx1 interacts within the C2 domain of PTEN (amino acids 186–274) (Figure 3F; Supplementary Figure S3C and D) and PTEN with the N terminus of Prdx1 (amino acids 1–40) and the C terminus of Prdx1 (amino acids 157–199) (Figure 3F, lower schematic and Supplementary Figure S3G). Computational analysis allowed us to narrow those interaction surfaces (Figure 3G). The images of Prdx1 and PTEN were generated from coordinates from the protein database 1d5r (Lee et al, 1999) and 2z9s (Matsumura et al, 2008), respectively. As shown for PTEN, the region of 186–251 consists of two double-stranded anti-parallel sheets connected through two flexible loops. Similarly, the 1–40 region of Prdx1 consists of a single double-stranded anti-parallel sheet and another, surface exposed single sheet strand. In Figure 3G, the Prdx-1 protein is shown only as the monomer and the helical region that lies at the dimer interface, residues 183–199, are also positioned in a surface exposed position that is obviously well poised to mediate a protein–protein interaction. Deleting the identified interaction sites in PTEN and Prdx1 altered enzyme activity of both enzymes (data not shown), which did not allow us to study the role of a physical interaction in protecting PTEN lipid phosphatase activity.

Figure 3.

(A) Epitope-tagged PTEN was expressed in 293T cells. Cell lysate was prepared under anaerobic conditions and immunoprecipitates were prepared as described in Materials and methods. A measure of 1000 μg of protein was immunoprecipitated (anti-PTEN antibody; Santa Cruz). Proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE. PTEN and Prdx1 proteins were detected by staining membranes with anti-PTEN (138G6, Cell Signaling) and anti-Prdx1 (Abcam) antibodies, respectively. (B) Epitope-tagged PTEN and Prdx1 wild type were co-expressed in 293T cells. Before lysis, cells were treated with increasing dosages of H2O2 as indicated for 15 min. Cell lysates were prepared under anaerobic conditions, and precipitated over night using HA-conjugated agarose beads. IPs were washed four times with argon-purged lysis buffer and analysed by western blotting. Proteins were detected with anti-PTEN, anti-Prdx1-SO2/-SO3 and anti-Prdx1 antibodies. Epitope-tagged Prdx1 migrates slower electrophoretically than endogenous Prdx1, labelled as HA–Prdx1. Epitope-tagged PTEN is labelled as Myc–PTEN. Anti-Prdx1-SO2/-SO3 can cross-react with Prdx2-4 and stains more intense in the IP proteins due to over night incubation and longer exposure to atmospheric oxygen. In contrast, lysates were immediately frozen (Supplementary Figure S3A and B). (C) Myc–PTEN and HA–Prdx1C51/172S were analysed as described under (B). Anti-Prdx1-SO2/-SO3 does not bind Prdx1C51/172S. (D) Recombinant His–PTEN (100 nM) was applied to equimolar GST or GST–Prdx1 and incubated over night. Glutathione sepharose (GST) beads were added for GST-pull down and analysed by western blotting. Input represents 1/50 of the total. (E) HA–Prdx1 wild type and cysteine to serine mutants of catalytically active Prdx1 cysteines were co-expressed with Myc-tagged PTEN wild type. HA–IPs were processed as under (B). Left side shows co-immunoprecipitations, right side shows expression of PTEN and Prdx1 cysteine to serine mutants. (F) Schematic domain structure of potential interaction sites of Prdx1 with PTEN (upper schematic) and PTEN with Prdx (lower schematic). (G) Identification of potential interaction sites using computer modelling (SwissPdb Viewer version 4; http://www.expasy.org/spdbv) (Guex and Peitsch, 1997). *Prdx1 N terminus.

Prdx1 interaction with PTEN protects and promotes PTEN lipid phosphates activity under oxidative stress

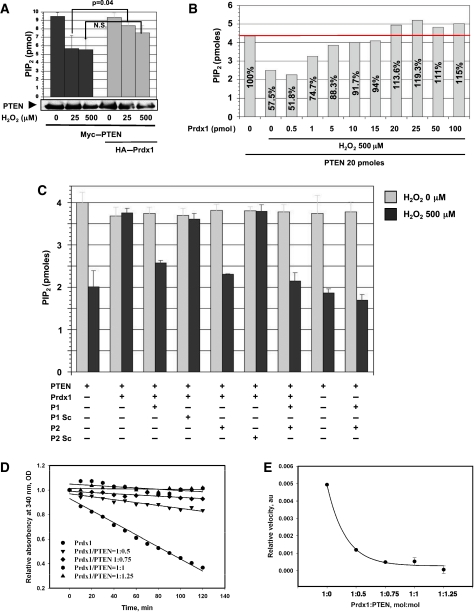

PTEN lipid phosphatase activity was fully protected by Prdx1 in cells under mild oxidative stress (25 μM H2O2) (Figure 4A), where Prdx1 was found to bind PTEN (Figure 3B). However, under higher oxidative stress treatment (500 μM H2O2), which resulted in decreased binding of PTEN and Prdx1 (Figure 3B), impaired PTEN's lipid phosphatase activity. Western blotting confirmed equal amounts of PTEN protein in the lipid phosphatase assay (Figure 4A, lower panel). To complement those results, we exposed recombinant purified His-tagged PTEN to H2O2 in the absence or presence of increasing amounts of purified recombinant Prdx1 and assayed PTEN for PI(3,4,5)P3 utilization. As expected (Figure 4B), in the presence of H2O2, we found that low molar amounts of Prdx1 protein weakly protected PTEN lipid phosphatase activity, whereas equimolar Prdx1 fully restored and further increases in Prdx1 protein amount did not enhance PTEN lipid phosphatase activity any more. Pre-incubation of PTEN in this assay with N-and C-terminal Prdx1 peptide replica (P1 and P2, respectively; peptide sequences were based on Prdx1 interaction mapping as shown in Supplementary Figure S3G and discussed for Figure 3G) decreased PTEN lipid phosphatase activity efficiently to 53%, which was comparable to PTEN activity observed with H2O2 treatment in the absence of Prdx1 (50%) (Figure 4C). Addition of P1 decreased PTEN lipid phosphatase activity only to 65%, whereas P2 lowered it to 57%. However, as shown in Figure 4D, the addition of His-purified PTEN to recombinant Prdx1 inhibited Prdx1 peroxidase activity. Under our experimental conditions, the kinetics of NADPH oxidation to NADP+ were linear and the Prdx1 inhibition was proportional to molar amount of PTEN and reached saturation (completed inhibition) at PTEN/Prdx1=1:1 (mol/mol) ratio. Moreover, an increase in PTEN ratio lowered the velocity of Prdx1 peroxidase activity (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

(A) Epitope-tagged Myc–PTEN and HA–Prdx1 were co-expressed in 293T cells, which were treated with H2O2 for 15 min, as indicated. Cell lysates were prepared under anaerobic conditions, and precipitated over night as described above by using anti-PTEN antibody. PTEN-immunoprecipitates were analysed for PI(3,4,5)P3-utilization in a 96-well plate assay as described in Materials and methods (triplicate samples). All results are presented as mean±s.e. (or difference) for at least two independent experiments. Equal PTEN protein amount was confirmed by western blotting. (B) 500 μM of H2O2 was added to either 20 pmoles of recombinant His-purified PTEN in the presence of different amounts of recombinant purified Prdx1 as indicated and described in Materials and methods. Experiment shown is representative of three independent studies. (C) PTEN activity was measured as described in (B) in the presence of peptides interfering with Prdx1 binding to PTEN. P1 (peptide 1) is replica of first N-terminal 21 amino acids (AS) of Prdx1; P1 Sc, scrambled sequence of P1; P2 (peptide 2), replica of last C-terminal 26 AS of Prdx1; P2 Sc, scrambled sequence of P2. The results are presented as mean±s.e. (or difference) for at least two independent experiments. (D) Prdx1 peroxidase activity was measured by a standard thioredoxin (Trx)/thioredoxin reductase (TrxR)/NADPH-coupled spectrophotometric assay (see Materials and methods for details). A measure of 20 pmoles of purified Prdx1 (Sigma) was incubated with 500 μM H2O2 and increasing molar amounts of purified His–PTEN as indicated. Prdx1 peroxidase activity (without PTEN) was about 68 nmol/mg protein/min under those conditions (extinction coefficient 6.62 mM−1 cm−1 for NADPH at 340 nm). Experiment shown is representative of three to four independent studies. (E) Relative reaction velocity of Prdx1 peroxidase activity from (D) was determined by plotting linear regression coefficient K (y=a−Kx, where y is the absorbency at 340 nm and x is time) versus various PTEN/Prdx1 (mol/mol) ratios. The results are presented as mean±s.e. (or difference) for at least two independent experiments.

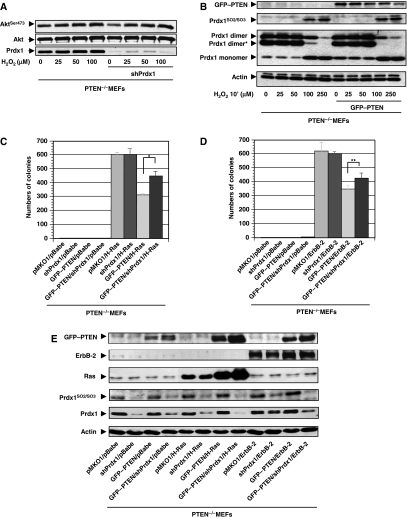

Prdx1 suppresses H-Ras and ErbB-2-induced transformation mainly via promoting PTEN activity

Next, we examined in PTEN−/−MEFs whether Prdx1 has an important function in PTEN-induced tumour suppression. Although Prdx1 knock down in PTEN−/−MEFs decreased pAktSer473 levels, H2O2 treatment of MEFs increased it equally in PTEN−/−MEFs and PTEN+/+MEFs (Figure 5A). Prdx1 is neither over-oxidized nor does it form less peroxidase active dimers in PTEN−/−MEFs compared with PTEN−/−MEFs reconstituted with GFP–PTEN, suggesting that in PTEN-null cells, Prdx1 activity is not compromised after H2O2 treatment (Figure 5B). PI3K/Akt signalling is also essential for oncogenic ErbB-2-induced transformation (Maroulakou et al, 2007), and Akt1 deficiency sufficiently suppresses tumour development in PTEN+/−mice (Chen et al, 2006). As shown for H-Ras (Figure 1B), Prdx1WT also prevented ErbB-2/neuT-induced transformation depending on its peroxidase activity (Supplementary Figure S5A). By using small hairpin (sh) RNA targeting Prdx1 mRNA (shPrdx1) in PTEN−/−MEFs, transformed by either H-RasV12 or ErbB-2/neuT, we showed that Prdx1 suppressed transformation mainly by regulating PTEN (Figure 5C–E). Although shPrdx1 expressed in PTEN−/−;H−RasV12MEFs or PTEN−/−;ErbB−2/neuT MEFs did not increase colony formation compared with PTEN−/−;H−Ras;pMKO1MEFs or PTEN−/−ErbB−2/neuT;pMKO1MEFs, in PTEN−/−;shPrdx1;GFP−PTEN,H−RasV12MEFs showed 1.5-fold increase in colony formation compared with PTEN−/−;pMKO1;GFP−PTEN,H−RasV12MEFs and PTEN−/−;shPrdx1;GFP−PTEN,ErbB−2/neuTMEFs and 1.35-fold increase in colony formation compared with PTEN−/−;pKMO1;GFP−PTEN;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs. Furthermore, a slight increase of Prdx1 oxidation was noted in PTEN−/−;pMKO1;H−RasV12MEFs compared with PTEN−/−;GFP−PTEN;H−RasV12MEFs and in PTEN−/−;pMKO1;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs compared with PTEN−/−;GFP−PTEN;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs. By using minimum dosages of two well-known PI3K inhibitors, Wortmannin (WM) and Ly294002 (Ly) that inhibited H2O2-induced Akt activity in Prdx1−/−MEFs less efficiently than in Prdx1+/+MEFs (Supplementary Figure S5B), we found that partial inhibition of PI3K/Akt activity translates into less efficient inhibition of H-Ras or ErbB-2-induced transformation in Prdx1−/−MEFs compared with Prdx1+/+MEFs (Table I): 5 nM WM reduced Prdx1−/−;H−RasV12MEFs colony number by <4%, 10 nM WM by 2.3%. However, 5 nM WM decreased Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs colony numbers by 46% and (P=<0.001) 10 nM WM by 67%. Similarly, 10 μM Ly decreased Prdx1−/−;H−RasV21MEFs colony number by 61% and in Prdx1+/+;H−RasV12MEFs by 73%. However, 10 μM Ly decreased colony number of Prdx1−/−;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs by only 53%, whereas in Prdx1+/+;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs by 75%. Moreover, 25 μM Ly decreased colony formation equally in Prdx1−/−;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs and Prdx1+/+;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs to 4–5%.

Figure 5.

(A) PTEN−/−MEFs were serum starved for 48 h and treated with H2O2 as indicated for 10 min. Protein lysates were analysed for pAktSer473 as described before. (B) PTEN−/−MEFs were infected with retrovirus expressing GFP–PTEN. After 5-day selection in puromycin (2 μg/ml), MEFs were serum starved, exposed for 10 min to H2O2 and analysed for Prdx1 oxidation and formation of dimeric structures by non-reducing SDS–PAGE. *Prdx1 hetero-dimer formation with other Prdxs. (C) PTEN−/−MEFs were infected with retrovirus expressing shPrdx1, GFP–PTEN, H-RasV12 or various vectors carrying resistance gene only (pBabe, pMKO1). MEFs were plated in soft agar. Colonies were counted after 21 days. *P<0.001 (Student's t-test). (D) As under C, except MEFs express ErbB-2/neuT instead of H-rasV12. **P<0.039 (Student's t-test). (E) Immunoblotting of MEFs from (C and D).

Table 1.

Prdx1−/−MEFs have a higher sensitivity to PI3K inhibitors in H-Ras or ErbB-2 induced transformation

| Wortmannin (nm) | H-Ras colony number in % | Ly294002 (μM) | H-Ras colony number in % | ErbB-2/neuT colony number in % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Prdx1−/− | 100±23.3 | 0 | Prdx1−/− | 100±11.2 | 100±4.6 |

| 5 | 96.3±5.7 | 10 | 38.3±15.2 | 47.3±6.6 | ||

| 10 | 97.8±13.5 | 25 | 5±10.1 | 3.2±4.1 | ||

| 0 | Prdx1+/+ | 100±4.1 | 0 | Prdx1+/+ | 100±11.2 | 100±4.6 |

| 5 | 55.9±12.5 | 10 | 26.3±5.5 | 25.1±6.6 | ||

| 10 | 32.7±24.4 | 25 | 4±8.7 | 3.2±4.8 | ||

| Prdx1−/−MEFs and Prdx1+/+MEFs were retrovirally infected with constructs carrying genes for H-RasV12 or ErbB-2/neuT (ErbB-2Val644Glu) and treated after plating in soft agar either with 10 or 25 μM Ly294002 every 2 days or Wortmannin 5 or 10 nM every day. Colonies were counted after 21 days. Decrease in colony formation (%) relates to untreated of the same genotype (%). This experiment is representative of three independent studies with two different sets of MEF clones from Prdx1 littermates. | ||||||

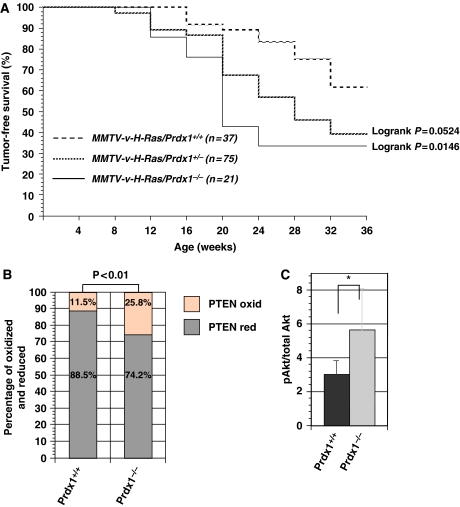

Loss of Prdx1 promotes H-Ras-induced mammary tumours and PTEN oxidation in mammary epithelial cells

MMTV/v-H-Ras mice transgenic mice are highly susceptible to mammary carcinomas due to the targeted over-expression of the activated Ras oncogene in their mammary glands (Sinn et al, 1987) and Akt1 ablation lowers the incidence of tumours in these mice (Maroulakou et al, 2007). In our experiment, we confirmed that Prdx1 plays a role in Ras-induced tumorigenesis in vivo (Figure 6A). In all, 60% of the Ras/Prdx1+/+ mice remained tumour free during the entire observation period of 36 weeks. In contrast, only 40% of the Ras/Prdx1+/− mice remained tumour free during that time with a median survival (T50) of 28 weeks, which indicated that the loss of one copy of Prdx1 accelerated Ras-induced breast cancer. Moreover, eliminating both copies of Prdx1 in MMTV/v-H-Ras mice (Ras/Prdx1−/−), the T50 for breast cancer was only 20 weeks. We then evaluated basal PTEN oxidation and pAktSer473 in mammary epithelial cells (MECs) from 16-week-old mice that had not developed tumours. Lack of Prdx1 increased basal PTEN oxidation (Figure 6B) and pAktSer473 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) The percentage of mice free of H-Ras-induced mammary tumours is shown in MMTV-v-H-Ras mice carrying only one, none, or both copies of the Prdx1 gene. (B) MECs (n=3) were isolated from MMTV-v-H-Ras mice/Prdx1−/− or MMTV-v-H-Ras mice/Prdx1+/+ and analysed on a non-reducing SDS–PAGE for PTEN oxidation as described above. Statistical analysis of PTEN oxidation was done using a χ2 test. (C) The same protein lysates were also analysed for Akt phosphorylation on Ser473, as described above. *Non-statistically significant.

Discussion

Compared with Prdxs, catalase peroxidase activity decomposes H2O2 with a >1000-fold higher KM (Chae et al, 1994a; Loewen et al, 2004) and therefore eliminates H2O2 with much higher efficiency. Thus, we cannot expect that Prdx1 scavenges H2O2 in considerable amounts, as shown in Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure S1A. Yet, Prdx1's peroxidase activity is important in preventing H-RasV12 (Figure 1B) or ErbB-2/neuT (Supplementary Figure S5A) induced transformation. Similar to the catalase knockout mice, all other currently published Prdxs knockout mice, show phenotypically no increased susceptibility to transformation (Ho et al, 1997). Therefore, Prdx1 may have a unique function amongst cellular peroxidases in tumour suppression, by affecting signalling directly through physical interaction with target enzymes. This was shown for c-Abl tyrosine kinase (Wen and VanEtten, 1997) and c-Jun terminal kinase (Kim et al, 2006). As described here for PTEN (Figure 3B), oxidative stress induced Prdx1 to dissociate, which in case of c-Abl (Neumann et al, 1998) and JNK (Kim et al, 2006) resulted in kinase activation. The Prdx1:PTEN heterodimer is most likely formed in a 1:1 molar ratio, as (1) the Prdx1 preservation of PTEN lipid phosphatase activity under oxidative stress is achieved by a 1:1 (mol:mol) ratio of Prdx1 and PTEN and could not be further increased by excess of Prdx1 (Figure 4B) and (2) Prdx1C51/172S, which is unable to form dimeric structures (Chae et al, 1994b), bound to PTEN and did not dissociate under H2O2 treatment (Figure 3C). Therefore, these data provide compelling evidence that Prdx1 may bind PTEN as a monomer.

We further propose that the Prdx1:PTEN interaction is essential for protecting PTEN from oxidation-induced inactivation (Figure 4C), as Prdx1 C- and N-terminal peptide replica, which were designed based on our mapping studies and computer modelling to block PTEN docking sites on Prdx1 (Figure 3F and G; Supplementary Figure S3E), resulted after H2O2 treatment in a 47% reduction of PTEN activity. This was comparable to PTEN activity after H2O2 treatment in the absence of Prdx1 (50%) (Figure 4C). The Prdx1 N terminus, which includes Cys51, may have an important function in regulating the H2O2-induced dissociation of the Prdx1:PTEN complex, as Cys51 when replaced by a serine enhances Prdx1 binding to PTEN (Figure 3D). X-ray crystallography of Prdxs suggested significant conformational changes, such as unwinding of the active site N-terminal helix, to form disulfides, as in reduced Prdxs, the sulfur atoms of the N- and C-terminal conserved cysteine residues are too far apart to react with each other (Schroder et al, 2000; Matsumura et al, 2008). Therefore, in the Prdx1:PTEN complex, increased H2O2 may oxidize Cys51 (Prdx1), thus, promoting unwinding of the PTEN-binding conformation of Prdx1 consequently inducing dissociation.

Over-oxidation of Prdx1 Cys51 occurs during catalysis and correlates with increasing amounts of Trx (Yang et al, 2002). The reduction of Cys51 by Trx inhibits the folding back of Cys51 into its pocket thereby exposing it to further oxidation by H2O2. The binding of PTEN to Prdx1 could have similar effects on Prdx1, thereby inhibiting sufficient reduction of Cys51 by Trx and decreasing Prdx1 peroxidase activity (Figure 4C and D). Alternatively, as it has been shown that Trx binds PTEN and inactivates its lipid phosphates activity, it could be that under our experimental conditions Trx is depleted from the Prdx1 scavenging system by binding PTEN (Meuillet et al, 2004). This seems unlikely though, as Trx was added in approximately 300-fold molar excess, which should provide a large Trx pool to reduce oxidized Prdx1 proteins.

We defined a novel interaction site of Prdx1 with PTEN in the C2 domain of PTEN (Figure 3F; Supplementary Figure S3D and E), which together with the N-terminal PTD, are both required for enzyme activity. Surface plasmon resonance analysis revealed that the C2 domain is essential for high-affinity membrane binding of PTEN (Das et al, 2003). Our data support this finding, as it has been shown recently through chemical proteomic strategy using cleavable lipid baits, that Prdx1 is a potential novel phosphoinositides-binding protein (Pasquali et al, 2007). Prdx1 may, therefore, stabilize PTEN binding to the plasma membrane, which in a recent analysis using single-molecule TIRF microscopy, lasts only for a few hundred milliseconds (Vazquez et al, 2006). Such short time of membrane binding could explain why we (Figure 2B, C, E and F; Supplementary Figure S2B and D) and others see only small amounts of PTEN oxidized after cell exposure to H2O2 or PDGF (Kwon et al, 2004). PDGF-induced H2O2 stems either from metabolized superoxide released by NADPH oxidases (NOXs) or the mitochondria and is considered a signalling molecule (Rhee, 2006). As discussed earlier (Leslie et al, 2003), such finding may be attributed to the proximity of NOXs complexes and PIP3. Over-expression of Nox1, in PDGF-stimulated NIH 3T3 cells rapidly increases PIP3 levels, in contrast to PI3K activity, suggesting that Nox1-induced superoxide enhances PIP3 levels by inactivating PTEN rather than activating PI3K. Expression of a peroxidase inactive Prdx2 leads to a rapid increase of PIP3 levels in growth factor stimulated cells, which is reversed by Prdx2WT (Kwon et al, 2004). In our hands however, Prdx2 did not bind PTEN, as we were unable to detect an interaction of Prdx2 and PTEN by immunoprecipitation (data not shown).

PTEN lipid phosphatase activity has an important function in tumour suppression (Tolkacheva and Chan, 2000; Koul et al, 2002) and Akt1 ablation protects (MMTV)-ErbB2/neu, MMTV-polyoma middle T and MMTV-v-H-Ras mice from breast cancer initiation (Skeen et al, 2006; Maroulakou et al, 2007). Here, we show that loss of Prdx1 increased basal, H2O2 and PDGF-induced Akt activity (Figure 2A, D and G) and Prdx1 peroxidase activity was essential in suppressing H-Rasv12 and ErbB-2/neuT-induced transformation (Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure S5A). Along those lines, Prdx1 ablation accelerated mammary tumorigenesis in MMTV-v-H-Ras mice and increased levels of pAktSer473 and PTEN oxidation in MECs from these mice (Figure 6A–C). Prdx1 tumour suppression seemed to occur largely via regulation of the PTEN and Akt. Knock down of Prdx1 in PTEN−/−MEFs did not significantly enhance H-Ras or ErbB-2-induced transformation (Figure 5C and D), whereas in transformed PTEN-containing MEFs, decrease in Prdx1 levels resulted in a gain of transformation: 1.5-fold for H-RasV12 and only 1.35-fold for ErbB-2/neuT, which we contributed to decreased Prdx1 knock down in PTEN−/−;shPrdx1;GFP−PTEN;ErbB−2/neuTMEFs compared with PTEN−/−;shPrdx1;GFP−PTEN;H−RasV12MEFs). Lack of PTEN also did not result in Prdx1 over-oxidation nor reduced expression (Figure 5B and E), suggesting that in PTEN-deficient cells, Prdx1 is acting as peroxidase.

However, we have to consider the regulation of other phosphatases or kinases by Prdx1 or H2O2 in Akt-driven tumorigenesis. SHIP-1 and 2 are known to dephosphorylate PIP3 to PtdIns (3,4)P2 (Vivanco and Sawyers, 2002). However, SHIP2 is not inactivated by oxidative stress (Leslie et al, 2003). PTEN−/−;shPrdx1MEFs showed decreased pAKTSer473 levels compared with PTEN−/−MEFs (Figure 5D), perhaps due to the activation of SHIP2 by small amounts of H2O2. However, H2O2 treatment of PTEN−/−;shPrdx1MEFs increased pAKTSer473 levels comparable to PTEN−/−MEFs, suggesting maybe a H2O2-induced inactivation of PP2A (Rao and Clayton, 2002), as loss of Prdx1 also inactivated PP2A activity (Supplementary Figure 2E). We also cannot exclude a regulation of PI3K by Prdx1, as H-Ras and ErbB-2/neuT transformed Prdx1−/−MEFs display a lesser sensitivity towards PI3K inhibitors (Table I; Supplementary Figure 5B), compared with Prdx1+/+MEFs.

In summary, oxidative stress and carcinogenesis are closely linked, however, molecular details, especially how oxidative stress promotes pro-oncogenic signalling pathways are scarce. Our studies shed some light on how H2O2 can promote oncogenic Ras and ErbB-2 signalling by providing evidence for the first time that the tumour suppressive function of PTEN and Prdx1 are closely related. The mechanistic details of the Prdx1 and PTEN interaction and its regulation in terms of Prdx1 peroxidase activity and PTEN oxidation will be important in future work.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise indicated. Ly294002, WM, antibodies against PTEN (138G6), Akt (11-E7), Akt-phosphoserine 473 (193H12), Akt-phosphothreonine 308 (244F9), phospho Akt substrate (110B7E) and HA-tag were purchased from Cell Signaling; Antibodies recognizing PTEN (A2B1), PTEN (N-19) and Actin (C-11) were purchased from Santa Cruz; antibodies against Prdx1 and Prdx1-SO2/-SO3 were purchased from Abcam; Ras antibody from Oncogene; ErbB-2 antibody from Biosource. HA-conjugated agarose beads were purchased from Roche. Amplex Red reagent: Molecular Probes. DMEM, FBS, Glutamax, NEAA, Pen/Strep, Sodium Pyruvate, DMEM without Phenol Red, PBS and PDGF stem from Invitrogen; GST-sepharose from Pharmacia. 6His–PTEN was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 from the fusion vector pProEx HTb PTEN and purified by standard protocols.

Retrovirus

The retrovirus was generated after conducting a transient transfection of retroviral constructs into a 293T/17 (ATCC) ecotropic-packaging cell line. Retroviral infection of MEFs was carried out for 4–6 h in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene. An antibiotic selection was carried out 24 h later until all uninfected cells were eliminated and stable polyclonal cell lines were generated.

Generation of MEFs

MEFs were generated from Prdx1+/− littermate matings in a C57BL/6J/129Sv background. Primary MEFs were harvested from E13.5 embryos as described earlier (Neumann et al, 2003). Primary Prdx1 and PTEN MEFs (passages 3–4) were immortalized by retroviral infection with pBabe-hygro DD p53 expressing dominant-negative p53 (Hahn et al, 2002) and selected with 150 μg/ml hygromycin for 14 days.

Amplex red assay

In total, 35 000 MEFs were plated (n=6) in 24-well plates (Costar 24) coated with fibronectin. On the day of the assay, cells were washed with PBS and repleted with serum-free and phenol red-free DMEM medium. Amplex Red reagent and horse radish peroxidase (HRP) were prepared as recommended by the manufacturer (HRP 0.2 U/ml). MEFs were incubated with Amplex Red/HRP solution at 37°C before the first reading (T0) at 540 nm on a plate reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5). Plates were kept in an incubator between readings. The resulting fluorescence (FLU) was compared with FLU from H2O2 standard curves and analysed.

Soft agar assays

P53DD-immortalized MEFs (Prdx1−/−, Prdx1+/+) were infected with retrovirus containing either Prdx1WT or Prdx1C172/51S, both subcloned into pQCXI-puro (Clontech) and selected 10 days in puromycin 2 μg/ml. Some clones were further infected with a retrovirus containing either H-RasV12 (pBabe-puro H-RasV12) (Yu et al, 2001) or wild-type ErbB-2 (pBabe-puro ErbB-2) (Yu et al, 2001) and selected in 5 μg/ml puromycin for another 5 days. MEFs were then resuspended in DMEM containing 0.53% agarose (Difco) and plated onto a layer of 0.7% agarose-containing medium in 3.5-cm plates in duplicate (10 000 cells per plate). Colonies were counted after 14–21 days.

Akt activity and PTEN oxidation

MEFs (1.8 × 105) were plated on 10-cm plates and serum-starved (0.25% FBS) for 48 h. Plates were then incubated with H2O2 (±Ly294002 or WM) as indicated. Akt and PTEN protein analysis were done as described earlier (Leslie et al, 2003) with slight modifications. Briefly, lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4; 1% Triton 100; 0.5 mM EDTA; 0.5 mM EGTA; 150 mM NaCl; 10% Glycerol; 50 mM NaF; 100 mM NaVO4; 40 mM β-Glycerophosphate) was degassed with Argon for 20 min before adding 1% TritonX-100; 2 mM PMSF; 5 mg/ml Aprotinin; N-ethylmaleimide 40 mM; and bovine catalase 100 μg/ml. Plates were transferred into an anaerobic/argon cabinet and were washed twice with cold degassed PBS. Cells were then scraped into lysis buffer and lysed on ice for 20 min before conducting quantitative analysis as described above. A measure of 65 μg of protein were analysed under non-reducing conditions with a 7.5% SDS–PAGE.

Co-immunoprecipitation

PTENWT (Addgene) was subcloned into a pQCXI vector (Clonetech) and N-terminally tagged with Myc epitope. Prdx1WT and Prdx1C51/172S, Prdx1C51S, Prdx1C172S (generated by site-specific mutagenesis) were subcloned into a pCGN vector and N-terminally tagged with an HA epitope. All constructs were transfected into 293T/17 (ATCC) cells using Fugene transfection reagent (Roche). Cells were harvested 72 h later for protein lysis under anaerobic conditions (as described above). A measure of 1000 μg protein was immunoprecipitated using anti-HA affinity matrix overnight at 4°C before washing four times with degassed lysis buffer before analysis on 4–12% gradient SDS–PAGE. Proteins were detected as described above.

GST-pull down

BL21(DE3) were transformed and cultured overnight with pGEX-4T-2 (Amersham) ligated earlier with Prdx1. At absorbance of 0.6–0.8 at 600 nm, GST–Prdx1 expression was induced by the addition of IPTG (200 μM). Bacterial pellets were re-suspended using fusion protein buffer containing 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM PMSF, 5 mM benzamidine hydrochloride hydrate and 3 μM aprotinin. Lysate was then sonicated and proteins were solubilized by the addition of Triton X-100 (2%). After incubation of supernatant with glutathione affinity matrix, the matrix was washed consecutively with 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaCl and the GST-tagged fusion protein was eluted from the matrix by incubation with 30 mM reduced glutathione. The fusion protein was then desalted into 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4) and concentrated by centrifugation using a Centricon 30 kD MWC filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Incubations of equimolar concentrations (100 nM) of GST–Prdx1 plus His–PTEN or GST–EV (empty vector) plus His–PTEN were performed in a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM PMSF, 5 mM benzamidine hydrochloride, 3 μM aprotinin and 1%Triton X-100. Mixtures were allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C before pre-washed glutathione agarose beads were added. The retained proteins were eluted from the resin by addition of 35 μl of 4 × loading buffer and analysed by 10% SDS gels.

PTEN Plasmids

Different lengths of cDNA fragments encoding human PTEN amino acids from 1–403 were subcloned from pSG5L HA–PTENWT (Addgene#10750), pSG5L–HA–PTENC124S (#10745), pSG5L–HA–PTEN1−274 (#10740), pSG5L–HA–PTEN1−373 (#10766), pSG5L–HA–PTENΔ89–138 (#10924), pGEX2T–PTENΔ274–342 (#10739) (Ramaswamy et al, 1999) at restriction sites BamHI/EcoRI. A double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding the Myc-tag sequence was inserted 5′ of the PTEN to generate Myc–PTEN. Inserts tagged with Myc tag were cloned into pQCXIP to generate the corresponding pQCXIP–Myc–PTEN plasmids; pQCXIP–MYC–PTEN1−185 or PTEN1−351 or PTEN186−351 or PTENΔ244−251 were generated by PCR mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Prdx1 N- and C-terminal truncation mutants were generated by Bal31 nuclease digest, fill-in with T4-polymerase and subcloned into pCGN-HA.

Recombinant Prdx1 activity assay

Prdx1 peroxidase activity was studied by standard Trx/Trx reductase (TrxR)/NADPH-coupled spectrophotometric assay as described (Chae et al, 1994b). Briefly, NADPH oxidation coupled to the reduction of H2O2 was monitored at 37°C as a decrease in A340 using a SpectraMax M5 plate reading spectrophotometer. The reaction was initiated by addition of the H2O2 (500 μM) as a substrate into a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 0.15 U TrxR, 18 μM Trx, 25 μM NADPH and 680 nM Prdx1 (Sigma). The effect of PTEN on Prdx1 activity was studied by titration of reaction mixture with indicated increasing amount of PTEN (0.25–1.25 PTEN/Prdx1 mol/mol ratio). All experimental data were normalized to initial (before addition of substrate) absorbency and fitted with linear regression (Sigma Plot 10, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Quality of fit was controlled by regression coefficient (R2⩾0.9).

PTEN inositol phosphatase activity

Myc–PTEN was expressed in 293T/17 cells in the presence or absence of HA–Prdx1. Cells were lysed as described above in phosphatase inhibitors free lysis buffer. PTEN proteins were immunoprecipitated from lysates with anti-PTEN (Santa Cruz) o/n as described above. IPs were then washed twice as described (Schwartzbauer and Robbins, 2001), followed by a final wash in PTEN enzyme reaction buffer (10 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT pH 7.2). The phosphatase reactions were done following manufacturer's instructions (Echelon Biosciences). Briefly, the immunoprecipitated PTEN proteins were incubated with PTEN enzyme reaction buffer for an appropriate amount of time at 37°C in a 96-well plate coated with PI(3,4,5)P3. After removal of PTEN proteins from plates, PI(4,5)P2 was determined according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in a microplate reader, and PI(4,5)P2 produced was calculated from a standard curve.

Recombinant PTEN inositol phosphatase activity

A measure of 20 pmol purified recombinant human His–PTEN was incubated with different amounts of Prdx1 (Sigma Aldrich) and 500 μM H2O2 in 20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 7.4) buffer at room temperature for 10 min. H2O2 was removed by Bio-Gel P-6 chromatography columns (Bio-Rad), following the manufacture's instructions. The protein mixture was then loaded onto PTEN activity assay plates as described above (Echelon Biosciences). Equal amount of PTEN was confirmed by western blot with the PTEN antibody. For Prdx1 peptide interference, 20 pmoles purified recombinant human His–PTEN was pre-incubated with 20-fold excess amount of peptides on ice in 20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 7.4) (for Peptide 1 or scramble peptide 1) or 0.2 mM Tris–Cl (pH 7.4) (peptide 2 or scramble peptide 2) for 1 h, the unbound peptides were removed by Microcon Ultracel YM-10 filters following the manufacture's instructions. The recovered PTEN–peptide mixtures were then incubated with 20 pmoles Prdx1 (Sigma Aldrich) and 500 μM H2O2 in 20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 7.4) buffer at room temperature for 10 min and further processed as described above. Peptide 1: MSSGNAKIGHPAPNFKATAVM; scrambled peptide 1: KTHPMPSIAAKFNAGSNAMVG; Peptide 2: PAGWKPGSDTIKPDVQKSKEYFSKQK; scrambled peptide 2: IKKSWKFGPGQPTSAPKQSKEVKYDD; all peptides had purity >75% and were purchased from Genscript, NJ.

PTEN−/−MEFs experiments

An optimal sequence for knock down of Prdx1 by sh (5′-GCTCAGGATTATGGAGTCTTA-3′) was identified from the TRC consortium (http://www.broad.mit.edu) and was subcloned into pMKO1 retroviral vector by AgeI/EcoRI digest. PTEN−/−MEFs were infected with retroviral supernatant containing either pMKO1–Prdx1shRNA or pMKO1 EV, and selected in puromycin 2 μg/ml for 1 week. GFP–PTEN was subcloned from pEGFP–C2–PTEN (Leslie et al, 2000) into pQCXIP at restriction sites of AgeI-EcoRI. PTEN−/−;pMKO1MEFs or PTEN−/−;shPrdx1MEFs were then transduced with GFP–PTEN retrovirus and selected in 6 μg/ml puromycin. Infection and selection with retrovirus expressing either H-RasV12 or ErbB-2/neuT was then challenged by 10 μg/ml puromycin.

MMTV-v-H-Ras mice lacking Prdx1

MMTV-v-H-Ras mice (Sinn et al, 1987) were purchased from Charles River. Prdx1+/−/MMTV-v-H-Ras mice were intercrossed to generate Prdx1−/−/MMTV-v-H-Ras and Prdx1+/+/MMTV-v-H-Ras mice. Mice were monitored twice a week for tumour appearance. Mouse mammary glands were isolated from age-matched 16-week-old female MMTV-v-H-ras/Prdx1−/− and MMTV-v-H-ras/Prdx1+/+ (n=3) mice following earlier described procedures (Fujiwara et al, 2005). Proteins were processed as described above.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1–S5

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Drs Yusuf Hannun, Peter Sicinski, Alex Toker, Steve Rosenzweig and Scott Eblen for fruitful discussions. We thank Ningfei An and Joe Blumer for assistance with GST-pull down experiments and Joseph Moore for editorial assistance. We thank Dr Rick Van Etten for sharing the Prdx1-constructs and knockout mice and Vic Stambolic for providing PTEN−/−MEFs. We also thank Dr William Sellers for sharing the PTEN wild-type construct through Addgene. This work was supported by grants from the NIEHS-K22 ES012985, ACS-IRG-97-219-05, Claudia Adams Barr Award-DFCI. All (CAN), and Abney research Foundation-MUSC (JC) and (AK).

References

- Chae HZ, Chung SJ, Rhee SG (1994a) Thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase from yeast. J Biol Chem 269: 27670–27678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae HZ, Uhm TB, Rhee SG (1994b) Dimerization of a thiol specific antioxidant and the essential role of cystein 47. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 47: 7022–7026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, Xu PZ, Peng XD, Chen WS, Guzman G, Yang X, Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP, Hay N (2006) The deficiency of Akt1 is sufficient to suppress tumor development in Pten+/− mice. Genes Dev 20: 1569–1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Dixon JE, Cho W (2003) Membrane-binding and activation mechanism of PTEN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 7491–7496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egler RA, Fernandes E, Rothermund K, Sereika S, de Souza-Pinto N, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Prochownik EV (2005) Regulation of reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and c-Myc function by peroxiredoxin 1. Oncogene 24: 8038–8050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Bandi M, Nitta M, Ivanova E, Bronson R, Pellman D (2005) Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53-null cells. Nature 437: 1043–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18: 2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn WC, Dessain SK, Brooks MW, King JE, Elenbaas B, Sabatini DM, DeCaprio JA, Weinberg RA (2002) Enumeration of the simian virus 40 early region elements necessary for human cell transformation. Mol Cell Biol 22: 2111–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y-S, Magnenat J-L, Bronson R, Jin C, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk C (1997) Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia. J Biol Chem 272: 16644–16651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson JN, Jin J, Cardiff RD, Woodgett JR, Muller WJ (2004) Activation of Akt-1 (PKB-alpha) can accelerate ErbB-2-mediated mammary tumorigenesis but suppresses tumor invasion. Cancer Res 64: 3171–3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniry M, Parsons R (2008) The role of PTEN signaling perturbations in cancer and in targeted therapy. Oncogene 27: 5477–5485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Lee WS, Ip C, Chae HZ, Park EM, Park YM (2006) Prx1 suppresses radiation-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase signaling in lung cancer cells through interaction with the glutathione S-transferase Pi/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase complex. Cancer Res 66: 7136–7142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul D, Jasser SA, Lu Y, Davies MA, Shen R, Shi Y, Mills GB, Yung WK (2002) Motif analysis of the tumor suppressor gene MMAC/PTEN identifies tyrosines critical for tumor suppression and lipid phosphatase activity. Oncogene 21: 2357–2364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J, Lee S, Yang K, Ahn Y, Kim Y, Stadtman ER, Rhee SG (2004) Reversible oxidation and inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN in cells stimulated with peptide growth factors. PNAS 101: 16419–16424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JO, Yang H, Georgescu MM, Di Cristofano A, Maehama T, Shi Y, Dixon JE, Pandolfi P, Pavletich NP (1999) Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell 99: 323–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SR, Yang KS, Kwon J, Lee C, Jeong W, Rhee SG (2002) Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J Biol Chem 277: 20336–20342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie N, Bennet D, Lindsay Y, Stewart H, Gray A, Downes C (2003) Redox regulation of PI3-kinase signaling via inactivation of PTEN. EMBO J 22: 5501–5510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie NR, Gray A, Pass I, Orchiston EA, Downes CP (2000) Analysis of the cellular functions of PTEN using catalytic domain and C-terminal mutations: differential effects of C-terminal deletion on signalling pathways downstream of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J 346 (Pt 3): 827–833 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Zhu T, Guan KL (2004) Transformation potential of Ras isoforms correlates with activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but not ERK. J Biol Chem 279: 37398–37406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K, Counter C (2005) Reduction in the requirement of oncogenic Ras signaling to activation of PI3K/AKT pathway during tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell 8: 381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen PC, Carpena X, Rovira C, Ivancich A, Perez-Luque R, Haas R, Odenbreit S, Nicholls P, Fita I (2004) Structure of Helicobacter pylori catalase, with and without formic acid bound, at 1.6 A resolution. Biochemistry 43: 3089–3103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroulakou IG, Oemler W, Naber SP, Tsichlis PN (2007) Akt1 ablation inhibits, whereas Akt2 ablation accelerates, the development of mammary adenocarcinomas in mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-ErbB2/neu and MMTV-polyoma middle T transgenic mice. Cancer Res 67: 167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura T, Okamoto K, Iwahara S, Hori H, Takahashi Y, Nishino T, Abe Y (2008) Dimer-oligomer interconversion of wild-type and mutant rat 2-Cys peroxiredoxin: disulfide formation at dimer-dimer interfaces is not essential for decamerization. J Biol Chem 283: 284–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuillet EJ, Mahadevan D, Berggren M, Coon A, Powis G (2004) Thioredoxin-1 binds to the C2 domain of PTEN inhibiting PTEN's lipid phosphatase activity and membrane binding: a mechanism for the functional loss of PTEN's tumor suppressor activity. Arch Biochem Biophys 429: 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CA, Fang Q (2007) Are peroxiredoxins tumor suppressors? Curr Opin Pharmacol 7: 375–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CA, Krause DS, Carman CV, Das S, Devendra D, Abraham JL, Bronson RT, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH, Van Etten RA (2003) Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defense and tumor suppression. Nature 424: 561–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CA, Wen ST, Van Etten RA (1998) Role of the c-Abl tyrosine kinase in the cellular response to oxidative stress. Blood 92: 1 (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali C, Bertschy-Meier D, Chabert C, Curchod ML, Arod C, Booth R, Mechtler K, Vilbois F, Xenarios I, Ferguson CG, Prestwich GD, Camps M, Rommel C (2007) A chemical proteomics approach to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in macrophages. Mol Cell Proteomics 6: 1829–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters GH, Frimurer TM, Olsen OH (1998) Electrostatic evaluation of the signature motif (H/V)CX5R(S/T) in protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Biochemistry 37: 5383–5393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Vazquez F, Batt DB, Perera S, Roberts TM, Sellers WR (1999) Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2110–2115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RK, Clayton LW (2002) Regulation of protein phosphatase 2A by hydrogen peroxide and glutathionylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293: 610–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG (2006) Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 312: 1882–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder E, Littlechild JA, Lebedev AA, Errington N, Vagin AA, Isupov MN (2000) Crystal structure of decameric 2-Cys peroxiredoxin from human erythrocytes at 1.7 A resolution. Structure 8: 605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzbauer G, Robbins J (2001) The tumor suppressor gene PTEN can regulate cardiac hypertrophy and survival. J Biol Chem 276: 35786–35793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H, Shao J, DuBois RN (2001) Akt/PKB activity is required for Ha-Ras-mediated transformation of intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 276: 14498–14504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinn E, Muller W, Pattengale P, Tepler I, Wallace R, Leder P (1987) Coexpresson of MMTV/v-Ha-ras and MMTV/c-myc genes in transgenic mice: synergistic action of oncogenes in vivo. Cell 49: 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeen JE, Bhaskar PT, Chen CC, Chen WS, Peng XD, Nogueira V, Hahn-Windgassen A, Kiyokawa H, Hay N (2006) Akt deficiency impairs normal cell proliferation and suppresses oncogenesis in a p53-independent and mTORC1-dependent manner. Cancer Cell 10: 269–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger JM, Siderovski DP, Mak TW (1998) Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell 95: 29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkacheva T, Chan AM (2000) Inhibition of H-Ras transformation by the PTEN/MMAC1/TEP1 tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene 19: 680–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Matsuoka S, Sellers WR, Yanagida T, Ueda M, Devreotes PN (2006) Tumor suppressor PTEN acts through dynamic interaction with the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3633–3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco I, Sawyers CL (2002) The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 489–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen S, VanEtten R (1997) The Pag gene product, a stress-induced protein with antioxidant properties, is an Abl SH3-binding protein and a physiological inhibitor of c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity. Genes Dev 11: 2456–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo HA, Kang SW, Kim HK, Yang KS, Chae HZ, Rhee SG (2003) Reversible oxidation of the active site cysteine of peroxiredoxins to cysteine sulfinic acid. Immunoblot detection with antibodies specific for the hyperoxidized cysteine-containing sequence. J Biol Chem 278: 47361–47364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KS, Kang SW, Woo HA, Hwang SC, Chae HZ, Kim K, Rhee SG (2002) Inactivation of human peroxide 1 during catalysis as the result of the oxidation of the catalytic site to cysteine-sulfinic acid. J Biol Chem 277: 38029–38036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Geng Y, Sicinski P (2001) Specific protection against breast cancers by cyclin D1 ablation. Nature 411: 1017–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZY, Dixon JE (1993) Active site labeling of the Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase: the determination of the pKa of the active site cysteine and the function of the conserved histidine 402. Biochemistry 32: 9340–9345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1–S5