Summary

Background

Mild cerebral injury might cause subtle defects in cognitive function that are only detectable as the child grows older. Our aim was to determine whether infants receiving resuscitation after birth, but with no symptoms of encephalopathy, have reduced intelligence quotient (IQ) scores in childhood.

Methods

Three groups of infants were selected from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: infants who were resuscitated at birth but were asymptomatic for encephalopathy and had no further neonatal care (n=815), those who were resuscitated and had neonatal care for symptoms of encephalopathy (n=58), and the reference group who were not resuscitated, were asymptomatic for encephalopathy, and had no further neonatal care (n=10 609). Cognitive function was assessed at a mean age of 8·6 years (SD 0·33); a low IQ score was defined as less than 80. IQ scores were obtained for 5953 children with a shortened version of the Weschler intelligence scale for children (WISC-III), the remaining 5529 were non-responders. All children did not complete all parts of the test, and therefore multiplied IQ values comparable to the full-scale test were only available for 5887 children. Results were adjusted for clinical and social covariates. Chained equations were used to impute missing values of covariates.

Findings

In the main analysis at 8 years of age (n=5887), increased risk of a low IQ score was recorded in both resuscitated infants asymptomatic for encephalopathy (odds ratio 1·65 [95% CI 1·13–2·43]) and those with symptoms of encephalopathy (6·22 [1·57–24·65]). However, the population of asymptomatic infants was larger than that of infants with encephalopathy, and therefore the population attributable risk fraction for an IQ score that might be attributable to the need for resuscitation at birth was 3·4% (95% CI 0·5–6·3) for asymptomatic infants and 1·2% (0·2–2·2) for those who developed encephalopathy.

Interpretation

Infants who were resuscitated had increased risk of a low IQ score, even if they remained healthy during the neonatal period. Resuscitated infants asymptomatic for encephalopathy might result in a larger proportion of adults with low IQs than do those who develop neurological symptoms consistent with encephalopathy.

Funding

Wellcome Trust.

Introduction

Mild degrees of hypoxia or other damaging processes during birth might cause impaired cognitive function in later life. The theory of a continuum of reproductive casualty1 suggests that although severe perinatal cerebral events cause death or obvious neurological deficit, mild events might cause subtle defects in cognitive function that are only detectable as the child grows older. Clinically important brain damage is widely believed to occur only if the hypoxic injury causes encephalopathy during the neonatal period,2,3 but evidence has been difficult to obtain. Even in infants with encephalopathy, the profile of cognitive effect is unclear. Since mild perinatal hypoxic events are more frequent than severe events, the long-term effect on the population could be substantial.

We recently reported a reduced intelligence quotient (IQ) in men at about 18 years of age, who had a low Apgar score at birth but did not develop encephalopathy.4 Previous small studies might not have had sufficient statistical power to detect such small differences in IQ.5,6 The Apgar score is commonly used to measure condition at birth, but the test is often criticised for being subjective and poorly reproducible.7 By contrast, the need for active resuscitation is a specific sign of delayed onset of respiration and could therefore indicate recent cerebral injury, especially hypoxia–ischaemia. In animal models, substantial fetal hypoxia was followed by delayed onset of respiration after birth,8 although other causes of poor condition at birth are infection,9 pre-existing fetal disorders,10 and congenital anomalies.11,12

We aimed to investigate whether childhood IQ score is affected by physiological compromise of a severity to warrant resuscitation during birth in infants who do or do not subsequently develop encephalopathy.

Methods

Patients

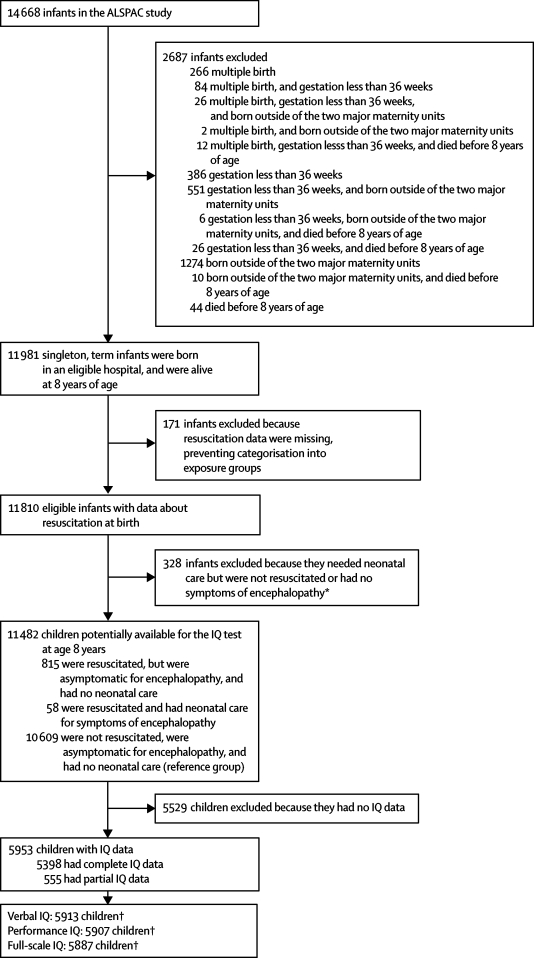

11 981 singleton infants, born at or after 36 weeks' gestation at two major maternity units in the study area, and alive at 8 years of age (figure), were selected from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). The ALSPAC cohort consists of more than 80% of children who were born in Bristol, UK, between April 1, 1991, and Dec 31, 1992, and contains data for 14 688 infants. Data for cohort members and their families are regularly obtained from self-completed questionnaires or half-day clinics, or are retrieved from routine medical or educational records.

Figure.

Study profile

*Infants excluded to ensure that the effect of resuscitation and encephalopathy on IQ was not biased by other diseases. †Verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ did not always need full subtest data for calculation.

499 infants were excluded from the study because resuscitation data were missing or they needed neonatal care but were not resuscitated or had no symptoms of encephalopathy (figure). Three groups were defined from the remaining 11 482 infants (figure): those who were resuscitated but were asymptomatic for encephalopathy and had no further neonatal care (n=815), those who were resuscitated and needed neonatal care for symptoms of encephalopathy (n=58), and the reference group of healthy infants who were not resuscitated, were asymptomatic for encephalopathy, and had no further neonatal care (n=10 609).

Ethical approval for the study was given by the ALSPAC law and ethics committee and the local research ethics committees. One parent of every child signed consent for enrolment of the child in to the ALSPAC study.

Procedures

Information about resuscitation and perinatal health was retrieved from computer records for 12 799 infants (87% of the cohort) born at two major maternity units. We deemed infants to have evidence of physiological compromise if they required either positive pressure respiratory support (face mask or endotrachael tube) or cardiac compressions at birth. Seizures, jitteriness, high-pitched cry, hypotonia or hypertonia, or hyper-reflexia were regarded as symptoms of encephalopathy. Although disturbances of consciousness were not prospectively recorded, seizures and disturbances in tone are central features for clinical diagnosis of neonatal encephalopathy.13

Cognitive function was assessed at a half-day clinic when study participants were a mean age of 8·6 years (SD 0·33); IQ data was gathered from 5953 children. Parents and children were initially invited to attend by letter; if there was no response, another letter was followed by telephone or personal contact, and a final letter was sent after 3 months of no response. IQ was assessed with the most recent version of the Weschler intelligence scale for children at that time—WISC-III—which is divided into verbal and performance subtests (panel).14

Panel. Verbal and performance subtests of the WISC-III (Weschler intelligence scale for children) and the number of children that completed each subtest.

Verbal subtests

-

•

Information: a measure of the child's general knowledge and acquired facts (n=5937)

-

•

Arithmetic: a measure of mental arithmetic and numerical accuracy (n=5927)

-

•

Vocabulary: a measure of verbal fluency, word knowledge, and usage (n=5910)

-

•

Comprehension: a measure of social knowledge and maturation (n=5879)

-

•

Similarities: a measure of abstract, logical thinking, and reasoning (n=5939)

Performance subtests

-

•

Picture completion: a measure of the ability to recognise familiar items (n=5919)

-

•

Coding: a measure of visual-motor dexterity, memory, and non-verbal learning (n=5934)

-

•

Picture arrangement: a measure of the ability to interpret a story sequence (n=5858)

-

•

Block design: a measure of the ability to analyse and reproduce an abstract design (n=5900)

-

•

Object assembly: a measure of the ability to reassemble an object from component parts (n=5582)

The same shortened version of the test was administered to all children, but even though the test was shortened, the number of children that completed each question within the verbal and performance subtests differed because children became tired, frustrated, or began to lose concentration after different time periods (panel). Alternate questions were asked for every subtest, except for the coding subtest, to shorten the test. Raw scores from every subtest were multiplied to predict scores comparable with the full version of the test. Tables from the WISC manual were used to calculate verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ scores. For consistency with our previous work,4 a low IQ score was defined as less than 80.15

Potential confounders and modifying variables for the statistical analysis of the infants fell into perinatal and social categories. Perinatal factors were sex, parity, gestational age, birthweight, length and head circumference, method of birth, maternal hypertension, and neonatal sepsis. Social factors were maternal age, socioeconomic group,16 education, and car ownership, and housing tenure, crowding index (number of household members per room), and ethnicity.

Statistical analysis

Primary analyses investigated the association between resuscitation and a low score in the summary IQ variables (verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ). We used logistic regression models, with an IQ score of less than 80 as the binary outcome, and linear regression models, with IQ score as a continuous variable. Secondary analyses with the ten verbal and performance subtests (Panel), and the verbal and performance IQ tests as outcomes were used to further investigate the association. To adjust for possible confounders, the perinatal and social modifying variables were added to the model, in blocks of common variables (eg, socioeconomic factors). We assessed whether maternal occupation, education, and sex modified the association of resuscitation status with cognition by fitting appropriate interaction terms to the model. Ordinal variables were tested for linearity and were included in the model as linear terms if appropriate. The population attributable risk factor was calculated from the final logistic regression model.17

Since all children did not complete all parts of the IQ test, each analysis contained a slightly different number of children (figure): 5398 children had complete IQ data, 555 had incomplete data, and 5529 had no data. Our main analyses used all available data. For example, 5887 children supplied full-scale IQ data but only 4857 children had complete data on all exposure (resuscitation status), outcome (IQ data), and confounder variables. To reduce selection bias, the chained equations missing data method was used to impute the missing confounder values only (exposure or outcome data was not imputed).18 We were therefore able to report analyses for the same number of children for both crude and adjusted analyses.

We did sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of these missing data by imputing all variables including the outcome but not exposure data (n=11 482) and by use of a complete case-only analysis (n=4857), which restricted the analysis to participants with complete data about all exposure, outcome, and confounder variables.

We did two further sensitivity analyses. First, excluding infants who developed cerebral palsy (n=13), and second with the cutpoint for a low IQ score of less than 70. This second cutpoint identified infants with IQ scores about 2 SD from the mean and is regarded as exceptionally low.15 We also derived the association between a low Apgar score (less than 7) at 1 and 5 min of age, and the risk of a low IQ score in asymptomatic infants. We chose not to use Bonferonni corrections to adjust our p values for the multiple statistical tests done, because the IQ scores were strongly intercorrelated or interdependent, and therefore such an approach would be overly conservative. All analyses used Stata (version 9), and a two-tailed p value of less than 0·05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funding organisation did not participate in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Characteristics of 11 482 eligible infants (table 1) showed no substantial difference in socioeconomic group or maternal age between resuscitated and non-resuscitated infants. Mothers with infants who were resuscitated and were asymptomatic for encephalopathy were the least educated, followed by those in the reference group. First pregnancy and maternal hypertension were more common in resuscitated infants with encephalopathy than asymptomatic infants or the reference group. Maternal pyrexia during labour and caesarean section was more common in both resuscitated groups than in the reference group. Head circumference was slightly increased and both birthweight and the Apgar score were slightly decreased in resuscitated infants. Table 2 shows Apgar and resuscitation status in the three groups. A higher proportion of infants who were resuscitated and developed symptoms of encephalopathy went on develop cerebral palsy than was seen in the asymptomatic and reference groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of resuscitated infants, with or without symptoms of encephalopathy

| Reference group |

Resuscitated infants |

p value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | Symptoms of encephalopathy | ||||

| Prepregnancy factors | |||||

| Maternal age (years) (n=11 481) | 28·08 (4·96) | 27·87 (4·97) | 27·84 (4·74) | 0·499 | |

| Maternal socioeconomic group (n=9500)† | |||||

| Professional | 541 (6%) | 40 (6%) | 3 (6%) | 0·191 | |

| Managerial | 2766 (32%) | 189 (28%) | 9 (19%) | ||

| Skilled non-manual | 3374 (38%) | 286 (43%) | 24 (50%) | ||

| Skilled manual | 986 (11%) | 78 (12%) | 6 (13%) | ||

| Semi-skilled | 913 (10%) | 55 (8%) | 6 (13%) | ||

| Unskilled | 207 (2%) | 17 (3%) | 0 | ||

| Mother's highest educational qualification (n=10 258)†‡ | |||||

| CSE | 1864 (20%) | 157 (22%) | 8 (15%) | 0·026 | |

| Vocational | 921 (10%) | 69 (10%) | 5 (9%) | ||

| O Level | 3264 (34%) | 282 (39%) | 15 (28%) | ||

| A Level | 2145 (23%) | 146 (20%) | 16 (30%) | ||

| Degree | 1286 (14%) | 71 (10%) | 9 (17%) | ||

| Housing tenure (n=10 718)† | |||||

| Mortgaged or owned | 7347 (74%) | 566 (74%) | 45 (79%) | 0·565 | |

| Council rented | 1426 (14%) | 100 (13%) | 5 (9%) | ||

| Private rented | 1127 (11%) | 95 (13%) | 7 (12%) | ||

| Car ownership (n=10 727)† | |||||

| ≥1 | 8873 (90%) | 680 (90%) | 52 (91%) | 0·915 | |

| None | 1037 (11%) | 80 (11%) | 5 (9%) | ||

| Crowding index (number of household members per room) (n=10 566)† | |||||

| <0·5 | 4103 (42%) | 354 (47%) | 32 (57%) | 0·009 | |

| 0·5–0·75 | 4992 (51%) | 341 (45%) | 20 (36%) | ||

| 0·75–1 | 469 (5%) | 43 (6%) | 4 (7%) | ||

| 1+ | 193 (2%) | 15 (2%) | 0 | ||

| Ethnicity (n=11 255)† | |||||

| Non-white | 584 (6%) | 42 (5%) | 8 (14%) | 0·021 | |

| White | 9818 (94%) | 754 (95%) | 49 (86%) | ||

| Antenatal and intrapartum factors† | |||||

| Primiparous (n=11 482) | 4338 (41%) | 421 (52%) | 36 (62%) | <0·0001 | |

| Maternal hypertension (n=11 482) | 301 (3%) | 36 (4%) | 4 (7%) | 0·008 | |

| Maternal pyrexia (n=11 482) | 45 (0·4%) | 9 (1%) | 3 (5%) | <0·0001 | |

| Method of birth (n=11 481) | |||||

| Spontaneous cephalic | 8370 (79%) | 429 (53%) | 19 (33%) | <0·0001 | |

| Emergency caesarean section | 465 (4%) | 156 (19%) | 22 (38%) | ||

| Elective caesarian section | 415 (4%) | 39 (5%) | 6 (10%) | ||

| Instrumental | 1276 (12%) | 138 (17%) | 8 (14%) | ||

| Breech | 83 (1%) | 52 (6%) | 3 (5%) | ||

| Infants and post-partum factors | |||||

| Male (n=11 482)† | 5401 (51%) | 426 (52%) | 35 (60%) | 0·276 | |

| Gestation (weeks) (n=11 482) | 39·7 (1·4) | 39·8 (1·5) | 39·5 (1·7) | 0·025 | |

| Birthweight (g) (n=11 482) | 3459 (472) | 3443 (524) | 3227 (721) | 0·0007 | |

| Birth length (cm) (n=10 457) | 50·9 (2·4) | 51·0 (2·5) | 51·0 (2·4) | 0·490 | |

| Head circumference (cm) (n=10 579) | 34·8 (1·4) | 35·0 (1·4) | 35·1 (1·6) | 0·004 | |

| Apgar score at 1 min (n=11 482) | 9 (9–9) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (3–5) | <0·0001 | |

| Apgar score at 5 min (n=11 470) | 10 (9–10) | 9 (8–9) | 7 (6–9) | <0·0001 | |

| Developed cerebral palsy (n=11 482)† | 8 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) | 3 (5%) | <0·0001 | |

Data are mean (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables, median (IQR) for skewed continuous variables, or number of infants (%). Data are complete for only some covariates and therefore the denominator varies for different factors.

p values compare all three groups.

The percentages shown are based on the numbers in the individual groups rather than the whole group.

CSE=assessment at age 15–16 years; O Level=assessment at age 15–16 years; A Level=assessment at age 17–18 years.

Table 2.

Comparison between Apgar score and resuscitation status

| Not resuscitated | Resuscitated | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apgar score 1 min (n=11 482) | |||

| <7 | 373 (3%) | 675 (6%) | 1048 (9%) |

| 7–10 | 10 236 (89%) | 198 (2%) | 10 434 (91%) |

| Apgar score 5 min (n=11 470) | |||

| <7 | 3 (<1%) | 84 (1%) | 87 (1%) |

| 7–10 | 10 596 (92%) | 787 (7%) | 11 383 (99%) |

Data are number of infants (% of the whole group).

To assess selection bias, we compared the characteristics of the 5529 infants who had no IQ data with the 5953 infants who were included in the main analyses. Infants who had no IQ data were more likely than were those with at least some IQ data to have needed resuscitation, but the association was not significant (8·5% vs 7·6%, p=0·069). These infants had identical median Apgar scores at 1 min (9 [IQR 8–9] vs 9 [8–9]; p=0·70) and 5 min (10 [9–10] vs 10 [9–10]; p=0·31) after birth.

The mean IQ scores (table 3) showed a strong association of the performance IQ and full-scale IQ, and a non-significant association of the verbal IQ, with the condition of the infant at birth. Of the infants with low IQ scores (table 4), performance IQ and full-scale IQ were associated with resuscitation status, but verbal IQ was non-significantly associated.

Table 3.

Mean verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ scores for resuscitated infants, with or without symptoms of encephalopathy

| Reference group* |

Resuscitated infants |

p value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic (n=400) | Symptoms of encephalopathy (n=26) | |||

| Verbal IQ (n=5913) | 107·6 (16·6) | 106·4 (17·3) | 101·0 (18·9) | 0·06 |

| Performance IQ (n=5907) | 100·0 (16·9) | 99·7 (17·3) | 88·1 (20·6) | 0·002 |

| Full-scale IQ (n=5887) | 104·6 (16·3) | 103·8 (17·1) | 94·5 (19·9) | 0·005 |

Data are mean (SD).

Verbal IQ n=5487; performance IQ n=5481; full-scale IQ n=5461.

p values compare all three groups.

Table 4.

Proportion of low verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ scores for resuscitated infants, with or without symptoms of encephalopathy

| Reference group* |

Resuscitated infants |

p value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic (n=400) | Symptoms of encephalopathy (n=26) | |||

| Low verbal IQ (n=5913) | 253 (5%) | 26 (7%) | 2 (8%) | 0·179 |

| Low performance IQ (n=5907) | 707 (13%) | 52 (13%) | 11 (42%) | 0·0001 |

| Low full-scale IQ (n=5887) | 354 (7%) | 39 (10%) | 6 (23%) | 0·0004 |

Data are number of infants (%). The percentages shown are based on the numbers in the individual groups rather than the whole group.

Verbal IQ n=5487; performance IQ n=5481; full-scale IQ n=5461.

p values compare all three groups.

In the final logistic regression model (table 5) the need for resuscitation in asymptomatic infants was associated with a low full-scale IQ score, although there was little evidence for a specific association with either a low verbal or performance IQ separately. Infants who developed encephalopathy after resuscitation had an increased risk of a low performance and full-scale IQ, although the association with verbal IQ was not significant. The absolute risk of a low IQ score was 6·5% for reference group infants, 9·8% (risk difference 3·3% [95% CI 0·3–6·2]) for asymptomatic resuscitated infants, and 23·1% (risk difference 16·6% [0·4–32·8]) for resuscitated infants with encephalopathy.

Table 5.

Probability of low IQ score for resuscitated infants, with or without symptoms of encephalopathy

| Unadjusted odds ratio | p value | Adjusted odds ratio* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal IQ (n=5913) | ||||

| Reference group | 1·00 | 1·00 | ||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | 1·44 (0·95–2·18) | 0·088 | 1·42 (0·90–2·25) | 0·144 |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | 1·72 (0·40–7·35) | 0·461 | 2·01 (0·23–17·18) | 0·538 |

| Performance IQ (n=5907) | ||||

| Reference group | 1·00 | 1·00 | ||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | 1·01 (0·75–1·37) | 0·954 | 1·03 (0.75–1.42) | 0·860 |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | 4·95 (2·26–10·83) | <0·0001 | 4·62 (1.48–14.40) | 0·008 |

| Full-scale IQ (n=5887) | ||||

| Reference group | 1·00 | 1·00 | ||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | 1·56 (1·10–2·21) | 0·012 | 1·65 (1·13–2·43) | 0·010 |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | 4·33 (1·73–10·86) | 0·002 | 6·22 (1·57–24·65) | 0·009 |

Data are odds ratio (95% CI).

Adjusted for sex, neonatal sepsis, parity, gestational age, birthweight, length and head circumference, method of birth, ethnicity, housing tenure, crowding index, and maternal hypertension, education, socioeconomic group, car ownership, and age.

The population attributable risk fraction was used to assess the effect of resuscitation status on IQ score. The proportion of individuals with low IQ scores that might be attributable to the need for resuscitation at birth was 3·4% (95% CI 0·5–6·3) for asymptomatic infants and 1·2% (0·2–2·2) for those who developed symptoms of encephalopathy. For both the linear and logistic regression models, adjustment for confounding factors did not appreciably modify the associations between resuscitation and IQ scores. There was little evidence that the association between resuscitation status and IQ differed by sex (pinteraction=0·33), maternal education (pinteraction=0·65), or maternal socioeconomic group (pinteraction=0·72).

In the fully adjusted linear-regression analysis (table 6) the mean verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ scores were lower, but not significantly so, in asymptomatic resuscitated infants than were those in the reference group. Conversely, verbal, performance, and full-scale IQ scores were all significantly lower in infants who developed encephalopathy after resuscitation than in the reference group. In the IQ subtests, asymptomatic resuscitated infants had lower similarities scores than did the reference group. Resuscitated infants who developed encephalopathy had decreased vocabulary, comprehension, and object assembly scores, and there was non-significant evidence of reduced information and coding scores.

Table 6.

Difference in mean Weschler intelligence scale for children (WISC-III) scores for resuscitated infants, with or without symptoms of encephalopathy, compared with the reference group

| Unadjusted mean difference | p value | Adjusted mean difference* | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal subtests | |||||

| Information (n=5937) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·02 (−0·34 to 0·30) | 0·891 | −0·11 (−0·42 to 0·20) | 0·480 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −0·65 (−1·86 to 0·56) | 0·295 | −1·43 (−2·93 to 0·06) | 0·061 | |

| Arithmetic (n=5927) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·15 (−0·57 to 0·26) | 0·470 | −0·09 (−0·51 to 0·34) | 0·689 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −0·68 (−2·27 to 0·91) | 0·402 | −0·61 (−2·65 to 1·44) | 0·562 | |

| Vocabulary (n=5910) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | 0·05 (−0·40 to 0·49) | 0·843 | −0·01 (−0·44 to 0·42) | 0·962 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −1·58 (−3·27 to 0·12) | 0·068 | −2·53 (−4·61 to −0·44) | 0·018 | |

| Comprehension (n=5879) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·36 (−0·73 to 0·02) | 0·065 | −0·24 (−0·63 to 0·15) | 0·235 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −2·62 (−4·05 to −1·19) | 0·0003 | −2·28 (−4·16 to −0·39) | 0·018 | |

| Similarities (n=5939) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·49 (−0·89 to −0·08) | 0·018 | −0·52 (−0·92 to −0·12) | 0·010 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | 0·00 (−1·53 to 1·53) | 0·997 | −0·82 (−2·75 to 1·11) | 0·406 | |

| Performance subtests | |||||

| Picture completion (n=5919) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·04 (−0·42 to 0·33) | 0·829 | −0·06 (−0·44 to 0·33) | 0·769 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −1·83 (−3·25 to −0·41) | 0·011 | −1·25 (−3·10 to 0·61) | 0·189 | |

| Coding (n=5934) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·05 (−0·35 to 0·26) | 0·769 | 0·01 (−0·32 to 0·30) | 0·959 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −1·13 (−2·29 to 0·03) | 0·057 | −1·46 (−2·95 to 0·03) | 0·054 | |

| Picture arrangement (n=5858) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·11 (−0·60 to 0·37) | 0·644 | −0·28 (−0·79 to 0·22) | 0·274 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −1·11 (−2·95 to 0·72) | 0·234 | −1·70 (−4·13 to 0·73) | 0·169 | |

| Block design (n=5900) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·04 (−0·42 to 0·35) | 0·853 | −0·07 (−0·46 to 0·32) | 0·710 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −1·67 (−3·16 to −0·18) | 0·028 | −0·54 (−2·42 to 1·34) | 0·576 | |

| Object assembly (n=5582) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | 0·00 (−0·39 to 0·39) | 0·995 | 0·04 (−0·37 to 0·44) | 0·847 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −3·33 (−4·85 to −1·81) | <0·0001 | −3·13 (−5·19 to −1·07) | 0·003 | |

| Summary scores | |||||

| Verbal IQ (n=5913) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −1·17 (−2·86 to 0·53) | 0·178 | −1·18 (−2·79 to 0·43) | 0·152 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −6·56 (−13·00 to −0·12) | 0·046 | −9·15 (−16·95 to −1·35) | 0·022 | |

| Performance IQ (n=5907) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·33 (−2·05 to 1·40) | 0·710 | −0·52 (−2·25 to 1·20) | 0·553 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −11·87 (−18·42 to −5·33) | 0·0004 | −9·99 (−18·35 to −1·64) | 0·019 | |

| Full-scale IQ (n=5887) | |||||

| Asymptomatic resuscitated infants | −0·88 (−2·55 to 0·79) | 0·301 | −0·99 (−2·58 to 0·60) | 0·220 | |

| Resuscitated infants with encephalopathy | −10·09 (−16·42 to −3·77) | 0·002 | −10·64 (−18·32 to −2·97) | 0·007 | |

Data are mean difference in IQ scores (95% CI).

Adjusted for sex, neonatal sepsis, parity, gestational age, birthweight, length and head circumference, method of birth, ethnicity, housing tenure, crowding index, and maternal hypertension, education, socioeconomic group, car ownership, and age.

Complete case analysis of only infants with complete data (n=4857) showed strengthened, but less precise, associations between resuscitation status and a low IQ score from odds ratios: asymptomatic infants 1·78 (95% CI 1·16–2·72), p=0·008; infants with encephalopathy 11·36 (2·65–48·80), p=0·001. Repeat of the analysis with imputation of covariates and IQ data (n=11 482) showed some evidence of an association: asymptomatic infants 1·44 (1·03–2·02), p=0·033; infants with encephalopathy 3·59 (1·01–12·82), p=0·049. Full results from these other models are available from the authors on request.

In further sensitivity analyses, we repeated the analysis with the low IQ score cutpoint of 70, which provided results consistent with the main analysis, although, reduction in the absolute number of infants with low scores resulted in widened confidence intervals: asymptomatic infants 1·91 (0·97–3·75), p=0·060; infants with encephalopathy 8·22 (0·94–72·04), p=0·057. The analysis was also repeated with exclusion of infants who developed cerebral palsy and showed little effect on the association between resuscitation and low IQ score for asymptomatic infants (1·64 [1·12–2·40], p=0·012), but the association for infants with encephalopathy was not significant (3·69 [0·73–18·52], p=0·113). The profile of cognitive changes remained similar (data not shown). With an Apgar score of less than 7, the association between resuscitation and low IQ score for asymptomatic infants at 5 min of age was 1·34 (0·42–4·27), p=0·662.

Discussion

The profile of infant characteristics suggested that associations between resuscitation status and perinatal or social factors were consistent with the findings of previous studies.11,12 Resuscitation was associated with non-white ethnicity and poor maternal education. Infants with reduced birthweight, from primiparous mothers, or born by caesarean section or instrumental delivery also had increased risk of needing resuscitation at birth. We showed an association between resuscitation at birth and cognitive functioning at 8 years of age. Infants who needed resuscitation, even if they did not develop symptoms of encephalopathy in the neonatal period, had a substantially increased risk of a low full-scale IQ score. Infants who developed signs of encephalopathy after resuscitation showed about a five-times increase in low performance and full-scale IQ scores compared with the reference group.

The data suggest that mild perinatal physiological compromise might be sufficient to cause subtle neuronal or synaptic damage, and thereby affect cognition in childhood and potentially in adulthood. By comparison, substantial perinatal compromise presents with neonatal encephalopathy and large cognitive deficits. The study had restricted power to detect differences in individual IQ subtests, and deficits in cognitive function are likely to present with reduced scores in several overlapping tests. Consequently interpretation of the subtests in isolation should be done with caution. Myers'8 studies of animal models suggest that prolonged hypoxia might affect vascular watershed areas (between two major cerebral arteries) of the brain—namely, the frontal, parietal, and occipital cortex—whereas acute anoxic events might preferentially affect deeper structures—eg, the basal ganglia and brain stem. The results of this study are consistent with prolonged partial hypoxia.

Kaufman19 reports that resuscitated infants have reduced scores in vocabulary and comprehension tests, specifically single-word comprehension and logical abstract thinking, which are measures of verbal conceptualisation ability. These functions have been localised to the prefrontal cortex,20,21 and therefore reduced function is consistent with a watershed injury to the brain in both groups of infants in our study. By contrast, infants with severe physiological compromise in our study also had substantially reduced scores for visual-perceptual abilities and spatial skills, which could indicate injury to deeper structures such as the thalamus.22

Resuscitation was strongly associated with an increased risk of a low IQ score, but the association with the mean reduction in IQ was not significant, which could be a chance finding. However, this result could also be a biologically plausible outcome from physiological compromise at birth—eg, only a subgroup of infants would have experienced sufficient compromise to damage the relevant brain regions and impair cognitive performance. The fact that the neonatal brain can repair itself also suggests that many neonates would not show deficits in cognitive function during childhood and adulthood unless the injury at birth was sufficiently severe. Our results did show a small reduction in the mean IQ score in the asymptomatic group, which is consistent with the findings in our previous study.4

ALSPAC is a large cohort of a population broadly representative of those living in the rest of the UK,23,24 but we had restricted statistical power to detect robust associations in infants with probable hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy since the condition is rare (0·5%), and consequently the confidence intervals were wide. The proportion of infants who received resuscitation in this cohort is consistent with published work, in which the rate varies between 1%25 and 14%.26 This variation might be caused by the clinician's subjective decision to resuscitate, despite clear guidelines,27 which will result in some error of measurement. Since 5529 (48%) of the eligible infants did not attend the IQ testing session, a missing data method was used to investigate potential selection bias. We repeated the analysis with the fully imputed data (n=11 482) and complete-case only (n=4857) analyses to assess the effect of missing data and reached similar conclusions. Some infants who had neonatal encephalopathy might not have been correctly identified, either because of absence of resuscitation details, or by having unreported symptoms of encephalopathy. Whether this absence of data could cause important selection bias is unclear, but repetition of the analysis with all infants admitted for neonatal care after resuscitation showed similar results.

Our findings could also be explained by prenatal disorders causing poor birth condition and predisposition to cognitive dysfunction in later life. We were able to control for several common prenatal disorders (eg, sepsis, prematurity); we could not control for rare abnormalities (eg, neuromuscular disorders), but they are less likely to affect the recorded associations. We attempted to control for important confounders but some degree of residual confounding is possible. Additionally, although we were able to correct for several socioeconomic factors, we have not adjusted for antenatal alcohol consumption or smoking exposure, and therefore any possible confounding effect of these factors has not been corrected for.

Use of 100% oxygen at birth is associated with worse outcomes than the use of room air in infants who are resuscitated,28,29 possibly because of free-radical injury and pulmonary atelectasis. Infants in this study were born in the early 1990s when 100% oxygen was the only gas connected to resuscitation equipment in the study centres. Therefore resuscitated infants were probably exposed to high partial pressures of oxygen for longer periods than infants would be today. The proportion of the association between resuscitation and IQ that might be attributable to hyperoxic damage, secondary to the resuscitation process itself, is unclear. Therefore, our findings might not be applicable to infants born in the present day.

Population studies are valuable to assess the effect of hypoxia on cognitive function in childhood. Many of these studies use the Apgar score to measure hypoxia, but large interobserver variability has caused concern.7 Data from our study showed a reduction in IQ in asymptomatic infants with a low Apgar score. This result is consistent with our previous study,4 in which asymptomatic infants with an Apgar score below 7 at 5 min of age had an increased risk of a low IQ (n=176 524, odds ratio 1·35 [95% CI 1·07–1·69]). The IQ was measured as part of a compulsory examination at 18 years of age, and, consequently, direct comparison with the WISC-III at 8 years of age is difficult. Nevertheless, similar analysis with Apgar data gathered from ALSPAC participants provided a compatible, though less precise, result (n=6045, 1·34 [0·42–4·27]).

We are not aware of other studies that have shown an association between transient physiological compromise at birth and cognitive defects in subsequently healthy infants. Viggedal5 and Blackman6 and their colleagues have reported reduced cognition only in infants who developed symptoms of encephalopathy. However, these studies consisted of only 20 and 38 infants, respectively, and without signs of neurological function the statistical power was probably insufficient to detect the modest association noted in this study.

In our study, resuscitated infants with encephalopathy had a substantially increased risk of a low IQ score compared with both resuscitated infants who remained asymptomatic and the reference group. However, since asymptomatic infants were more common than those with encephalopathy, they would have a larger population effect if a causal relation exists between resuscitation and the risk of a low IQ score.

In the ALSPAC cohort, infants who received resuscitation but did not develop symptoms of encephalopathy had an increased risk of a low IQ score at age 8 years. If this were a causal relation, it could account for about one in 30 adults who have a low IQ, which is a larger proportion than is attributable to the infants who develop encephalopathy. These findings are consistent with a cerebral injury of sufficient severity to delay respiration, but insufficient to cause obvious symptoms of encephalopathy. Our results support the idea of a continuum of reproductive casualty.1 Education and training interventions targeted at obstetric and neonatal staff improve measures of birth condition,30 and the identified association could have important population benefits if it is shown to be causal. Physiological compromise before or during birth could damage areas of the brain that are critical for specific cognitive functions.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses. This research was funded by a fellowship award (077036) to DO from the Wellcome Trust. The UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, analysed the data, wrote the manuscript, and commented on the final draft.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pasamanick B, Rogers ME, Lilienfeld AM. Pregnancy experience and the development of behavior disorders in children. Am J Psychiatry. 1956;112:613–618. doi: 10.1176/ajp.112.8.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Obstetric Practice, ACOG; American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Fetus and Newborn, ACOG ACOG Committee Opinion. Number 333, May 2006 (replaces No. 174, July 1996): the Apgar score. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1209–1212. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200605000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLennan A. A template for defining a causal relation between acute intrapartum events and cerebral palsy: international consensus statement. BMJ. 1999;319:1054–1059. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7216.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odd DE, Rasmussen F, Gunnell D, Lewis G, Whitelaw A. A cohort study of low Apgar scores and cognitive outcomes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93:F115–F120. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.123745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viggedal G, Lundalv E, Carlsson G, Kjellmer I. Follow-up into young adulthood after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in term and near-term newborn infants. II. Neuropsychological consequences. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:1218–1226. doi: 10.1080/080352502320777469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackman JA. The value of Apgar scores in predicting developmental outcome at age five. J Perinatol. 1988;8:206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell CP, Kamlin CO, Davis PG, Carlin JB, Morley CJ. Interobserver variability of the 5-minute Apgar score. J Pediatr. 2006;149:486–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers RE. Two patterns of perinatal brain damage and their conditions of occurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112:246–276. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(72)90124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baskett TF, Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Allen AC. Predictors of respiratory depression at birth in the term infant. BJOG. 2006;113:769–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villar J, de Onis M, Kestler E, Bolanos F, Cerezo R, Bernedes H. The differential neonatal morbidity of the intrauterine growth retardation syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM. Antepartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: the Western Australian case-control study. BMJ. 1998;317:1549–1553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM. Intrapartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: the Western Australian case-control study. BMJ. 1998;317:1554–1558. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress. A clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:696–705. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500100030012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3rd edn. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV UK) 4th edn. Harcourt Assessment; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys . vols 1, 2, and 3. HM Stationary Office; London: 1991. (Standard Occupational Classification). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenland S, Drescher K. Maximum likelihood estimation of the attributable fraction from logistic models. Biometrics. 1993;49:865–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update. Stata J. 2005;5:681–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman A. Intelligent testing with the WISC-III. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veltman DJ, de Ruiter MB, Rombouts SA. Neurophysiological correlates of increased verbal working memory in high-dissociative participants: a functional MRI study. Psychol Med. 2005;35:175–185. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasquier F, Lebert F, Grymonprez L, Petit H. Verbal fluency in dementia of frontal lobe type and dementia of Alzheimer type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:81–84. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutton GN, Jacobson LK. Cerebral visual impairment in children. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:477–485. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters TJ, Golding J, Lawrence CJ, Fryer JG, Chamberlain GV, Butler NR. Delayed onset of regular respiration and subsequent development. Early Hum Dev. 1984;9:225–239. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(84)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golding J, Pembrey M, Jones R, the ALSPAC Study Team ALSPAC—the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. I. Study methodology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:74–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palme-Kilander C. Methods of resuscitation in low-Apgar-score newborn infants—a national survey. Acta Paediatr. 1992;81:739–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroll L, Twohey L, Daubeney PE, Lynch D, Ducker DA. Risk factors at delivery and the need for skilled resuscitation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;55:175–177. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resuscitation Council (UK) Resuscitation at birth: the newborn life support provider course manual. Resuscitation Council (UK); London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan A, Schulze A, O'Donnell CP, Davis PG. Air versus oxygen for resuscitation of infants at birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002273.pub3. CD002273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saugstad OD. Take a breath—but do not add oxygen (if not needed) Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:798–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Draycott T, Sibanda T, Owen L. Does training in obstetric emergencies improve neonatal outcome? BJOG. 2006;113:177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]