Abstract

Four feral cats and a raccoon dog purchased from a local collector on Aphaedo Island, Shinan-gun, where human Gymnophalloides seoi infections are known to be prevalent, were examined for their intestinal helminth parasites. From 2 of 4 cats, a total of 310 adult G. seoi specimens were recovered. Other helminths detected in cats included Heterophyes nocens (1,527 specimens), Pygidiopsis summa (131), Stictodora fuscata (4), Acanthotrema felis (2), Spirometra erinacei (15), toxocarids (4), and a hookworm (1). A raccoon dog was found to be infected with a species of echinostome (55), hookworms (7), toxocarids (3), P. summa (3), and S. erinacei (1). No G. seoi was found in the raccoon dog. The results indicate that feral cats and raccoon dogs on Aphaedo are natural definitive hosts for intestinal trematodes and cestodes, including G. seoi, H. nocens, and S. erinacei. It has been first confirmed that cats, a mammalian species other than humans, play the role of a natural definitive host for G. seoi on Aphaedo Island.

Keywords: Gymnophalloides seoi, Heterophyes nocens, Pygidiopsis summa, intestinal helminth, cat, raccoon dog

Gymnophalloides seoi Lee, Chai and Hong, 1993 (Trematoda: Gymnophallidae) is a minute intestinal fluke of humans and migratory birds, including the palearctic oystercatcher, Haematopus ostralegus [1-4]. Gerbils, hamsters, cats, rats, dogs, ducks, plovers, and several strains of mice were proved to be experimental definitive hosts [5,6]. High endemicity of human G. seoi infection and high infection rate of its metacercariae in oysters, Crassostrea gigas, were observed on several southwestern islands of the Republic of Korea [4]. The infection rates of humans and oysters have not been changing significantly even after repeated mass chemotherapy of people in the village with praziquantel [7]. Therefore, possible existence of natural definitive hosts other than man and oystercatchers has been suggested.

Stray cats or feral cats are nowadays frequently found in almost every place of the Republic of Korea, including coastal areas. They are suggested to be a natural definitive host for G. seoi, since they find foods including de-shelled raw oysters in a waste box or, in some cases, steal seafood in the kitchen of villagers in coastal areas. A raccoon dog with a similar life pattern to cats was also suspected as a source of G.seoi or other parasite eggs.

Heterophyid flukes, in particular Heterophyes nocens and Pygidiopsis summa, are another group of intestinal trematodes that infect humans in coastal areas [8,9]. The source of human infections is brackish water fish, including the mullet, goby, and perch produced from estuaries [9]. Cats purchased from a market in Seoul [10] and in Busan [11] were found to be infected with H. nocens and P. summa. However, no studies have been progressed on the infection status of cats caught in other localities of the Republic of Korea. The present study aimed to investigate the infection status of feral cats and a raccoon dog on Aphaedo Island, Shinan-gun with intestinal helminths. Aphaedo is a well-known endemic area of G. seoi and H. nocens infections [12,13].

The carcasses of 4 feral cats and a raccoon dog caught on Aphaedo Island by a villager were purchased. It was informed by the villager that the raccoon dog and a cat were obtained in January 2003, and 3 other cats were caught in February 2004. Their intestines were longitudinally opened with a pair of scissors in 0.85% saline and washed with the same solution until the supernatant became clear. The sediment of the intestinal contents was carefully examined for parasites using a stereomicroscope. The collected worms were fixed in 10% neutral formalin solution and identified using a light microscope after acetocarmine stain.

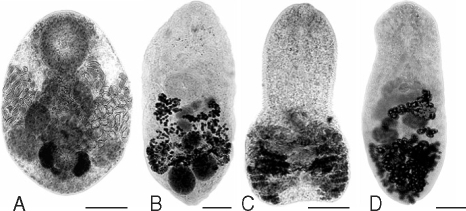

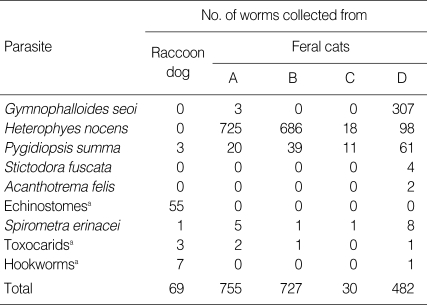

Adult G. seoi were recovered in 2 of 4 cats examined. One cat had 307 G. seoi adults and the other had 3 adults (Fig. 1; Table 1). These cats were co-infected with H. nocens (a total of 1,527 worms in 4 cats) and P. summa (131). In a raccoon dog, no adults of G. seoi were collected; however, 55 specimens of echinostomes (species undetermined) were obtained (Table 1). Other helminths, including toxocarids, hookworms, Stictodora fuscata, Acanthotrema felis, and Spirometra erinacei were also collected from the animals examined.

Fig. 1.

Intestinal flukes recovered from feral cats caught on Aphaedo Island, Shinan-gun, Jeollanam-do, a known endemic area of Gymnophalloides seoi. (A) G. seoi adult. Bar = 0.07 mm. (B) Heterophyes nocens adult. Bar = 0.1 mm. (C) Pygidiopsis summa adult. Bar = 0.1 mm. (D) Stictodora fuscata adult. Bar = 0.1 mm.

Table 1.

Infection status of intestinal parasites in feral cats and a raccoon dog collected from Aphaedo Island, Shinan-gun

aSpecies undetermined.

There had been no studies on intestinal parasites of raccoon dogs in the Republic of Korea. Therefore, this is the first report on intestinal parasites of raccoon dogs. As for cats, infections with several helminth species, i.e., Clonorchis sinensis, Paragonimus westermani, H. nocens, Metagonimus yokogawai, P. summa, Stellantchasmus falcatus, Heterophyopsis continua, Centrocestus sp., Echinochasmus perfoliatus, Echinoparyphium sp., A. felis, Pharyngostomum cordatum, S. erinacei, Taenia taeniaeformis, Anisakis simplex (larva), and Toxocara cati, have been reported [14-16]. In addition, an experimental study showed that cats were a fairly suitable host for G. seoi infection compared with ducks, chicks, and 6 kinds of mammals, including gerbils, hamsters, rats, dogs, guinea pigs, and mice [5]. The present study first demonstrates that feral cats are a natural definitive host for G. seoi infection. However, the epidemiological significance of feral cats in maintaining the endemicity in the surveyed area needs to be further clarified.

It is of note that infection of a clam with metacercariae of a gymnophallid, Meiogymnophallus fossarum, could change their host's orientation, behavior, and distribution [17,18]. The infected clams could be more easily visible in the sand substrate by the definitive host than non-parasitized clams, thus could facilitate predation. Oysters infected with metacercariae of G. seoi could be exposed more easily to oystercatchers or other definitive hosts, although this speculation has not been confirmed. It is well accepted that oystercatchers have the natural capacity of destroying oyster shells and eating the animal part. However, it is questioned how cats can open the shell of an oyster and consume the animal part. A possible explanation is that they may have consumed the wasted animal part of oysters, since stray or feral cats could easily find wasted oysters discarded in the trash box or in the yard in endemic areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by BK21 Human Life Sciences, Ministry of Education, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Lee SH, Chai JY, Hong ST. Gymnophalloides seoi n. sp. (Digenea: Gymnophallidae), the first report of human infection by a gymnophallid. J Parasitol. 1993;79:677–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SH, Chai JY. A review of Gymnophalloides seoi (Digenea: Gymnophallidae) and human infections in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2001;39:85–118. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2001.39.2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryang YS, Yoo JC, Lee SH, Chai JY. The Palearctic oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus, a natural definitive host for Gymnophalloides seoi. J Parasitol. 2000;86:418–419. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0418:TPOHOA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai JY, Choi MH, Yu JR, Lee SH. Gymnophalloides seoi: a new human intestinal trematode. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:109–112. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SH, Park SK, Seo M, Guk SM, Choi MH, Chai JY. Susceptibility of various species of animals and strains of mice to Gymnophalloides seoi infection and the effects of immunosuppression in C3H/HeN mice. J Parasitol. 1997;83:883–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryang YS, Yoo JC, Lee SH, Chai JY. Susceptibility of avian hosts to experimental Gymnophalloides seoi infection. J Parasitol. 2001;87:454–456. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0454:SOAHTE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chai JY, Lee GC, Park YK, Han ET, Seo M, Kim J, Guk SM, Shin EH, Choi MH, Lee SH. Persistent endemicity of Gymnophalloides seoi infection in a southwestern coastal village of Korea with special reference to its egg laying capacity in the human host. Korean J Parasitol. 2000;38:51–57. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2000.38.2.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai JY, Park JH, Han ET, Shin EH, Kim JL, Guk SM, Hong KS, Lee SH, Rim HJ. Prevalence of Heterophyes nocens and Pygidiopsis summa infections among residents of the western and southern coastal islands of the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai JY, Lee SH. Food-borne intestinal trematode infections in the Republic of Korea. Parasitol Int. 2002;51:129–154. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(02)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eom KS, Son SY, Lee JS, Rim HJ. Heterophyid tematodes (Heterophyopsis conrinua, Pygidiopsis summa and Heterophyes heterophyes nocens) from domestic cats in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1985;23:197–202. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1985.23.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohn WM, Chai JY. Infection status with helminthes in feral cats purchased from a market in Busan, Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2005;43:93–100. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2005.43.3.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SH, Chai JY, Lee HJ, Hong ST, Yu JR, Sohn WM, Kho WG, Choi MH, Lim YJ. High prevalence of Gymnophalloides seoi infection in a village on a southwestern island of the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:281–285. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chai JY, Nam HK, Kook J, Lee SH. The first discovery of an endemic focus of Heterophyes nocens (Heterophyidae) infection in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1994;32:157–161. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1994.32.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HS. A survey on helminth parasites of cats in Gyeongbug area. II. Trematodes. Korean J Vet Res. 1979;19:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huh S, Sohn WM, Chai JY. Intestinal parasites of cats purchased in Seoul. Korean J Parasitol. 1993;31:371–373. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1993.31.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn WM, Han ET, Chai JY. Acanthotrema felis n. sp. (Digenea: Heterophyidae) from the small intestine of stray cats in the Republic of Korea. J Parasitol. 2003;89:154–158. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0154:AFNSDH]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SS, Green RH. The relationship between parasite load, crawling behavior, and growth rate of Macoma balthica (L.) (Mollusca, Pelecypoda) from Hudson Bay, Canada. Can J Zool. 1991;69:2202–2208. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowers EA, Bartoli P, Russell-Pinto F, James BL. The metacercariae of sibling species of Meiogymnophallus, including M. rebecqui comb. nov. (Digenea: Gymnophallidae), and their effects on closely related Cerastoderma host species (Mollusca: Bivalvia) Parasitol Res. 1996;82:505–510. doi: 10.1007/s004360050153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]