Abstract

Products, styles, and social movements often catch on and become popular, but little is known about why such identity-relevant cultural tastes and practices die out. We demonstrate that the velocity of adoption may affect abandonment: Analysis of over 100 years of data on first-name adoption in both France and the United States illustrates that cultural tastes that have been adopted quickly die faster (i.e., are less likely to persist). Mirroring this aggregate pattern, at the individual level, expecting parents are more hesitant to adopt names that recently experienced sharper increases in adoption. Further analysis indicate that these effects are driven by concerns about symbolic value: Fads are perceived negatively, so people avoid identity-relevant items with sharply increasing popularity because they believe that they will be short lived. Ancillary analyses also indicate that, in contrast to conventional wisdom, identity-relevant cultural products that are adopted quickly tend to be less successful overall (i.e., reduced cumulative adoption). These results suggest a potential alternate way to explain diffusion patterns that are traditionally seen as driven by saturation of a pool of potential adopters. They also shed light on one factor that may lead cultural tastes to die out.

Keywords: cultural transmission, popularity, social influence, trends

What leads cultural tastes and practices to be abandoned? Products and styles become unpopular, areas of research fall out of favor, and political and social movements fade. Researchers have long been interested in understanding why such cultural items succeed (1–5). Cultural propagation, artistic change, and the diffusion of innovations have been examined across a variety of disciplines with the goal of understanding how things catch on (6–10). But when and why do cultural tastes and practices die?

It seems intuitive that changes in technology, advertising, or institutions lead old tastes to be replaced with newer ones (9, 11). But although their cooccurrence makes it tempting to infer that the decline of the old is driven by the rise of the new, the association may reflect an entirely separate process, similar to vacancy chains (12), where new items fill the vacuum left when old items die. Furthermore, focusing on external factors neglects the possibility that internal dynamics, such as the pattern and level of past popularity, may lead items to decline on their own (5, 13). Certain tastes are more popular than others, and because people prefer at least some differentiation (14–16), items that become too popular may be abandoned because they lose uniqueness. But in addition to absolute levels, people also attend to rates of change (17), and tastes also vary in how quickly the number of adopters or users changes over time.

We propose that tastes that quickly increase in popularity die faster. In many domains, the adoption decision depends not only on functional benefits, but also symbolic meaning, or what consuming the item communicates about the user (18–20). The social identity of the individuals consuming a given taste, for example, can change the meaning or value of that taste, and, consequently, influence choice (21–22). People choose tastes that communicate identities they want to signal and avoid tastes associated with other cultural groups to distinguish their identities (19–21, 23). Similarly, not only should a taste's popularity influence its symbolic meaning but so too should the rate of adoption. Just as too many people doing something in an identity-relevant domain can decrease its desirability (15), potential adopters may avoid items that catch on quickly because of concerns about their symbolic value. Fads are often perceived negatively, and if people think that sharply increasing items will be short lived, they may avoid such items to avoid doing something that may later be seen as a flash in the pan.

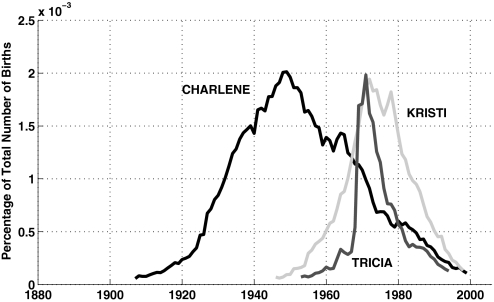

Such social dynamics are easier to examine when other factors are relatively silent, so we focus our analyses on first names. Social scientists have used names to study things like cultural assimilation and differentiation (24–26) and cultural change (5, 27), and names have distinct patterns of evolution of popularity. At their peak, both Charlene and Kristi counted for ≈0.20% of all female births in the United States, for example, but Kristi was adopted and abandoned much more quickly (see Fig. 1). Because there is less of an influence of technology or commercial effort on name choice, researchers have argued that names provide an excellent setting to study how adoption depends on internal factors such as histories of past popularity (5).

Fig. 1.

A few trajectories of first-name popularity (in the U.S.). Most names show a period of almost consistent increase in popularity, followed by a decline that leads to abandonment, but names differ in how quickly their popularity rises and declines.

We use both historical and survey data to investigate the relationship between adoption velocity and cultural abandonment. Our first study examines the popularity of first names over time. We demonstrate a positive relationship between adoption velocity and abandonment: Names that have become popular faster tend to be abandoned faster. In a second study, we assessed how likely expecting parents would be to give different names to their children. We found that future parents were more hesitant to adopt names that had recently experienced sharper increases in adoption. In addition, we found that this relationship is driven by symbolic concerns related to identity: Names that were adopted more quickly are seen as more likely to be short-lived fads, which decreased future parents' likelihood of adopting them.

Study 1: Analyses of the Rate of Abandonment

We used survival analyses to examine the relation between adoption velocity and subsequent abandonment of 2570 names given to children in France between 1900 and 2004 [see supporting information (SI) Text]. We treat a name as abandoned when the proportion of births with that name first drops below 10% of it past maximum (other methods yield similar results, (see SI Text). The analyses estimate the effect of several features of a name's adoption pattern on its hazard of abandonment (28). Given that preferences can be influenced by novelty (29) and popularity or the choices of others (1, 14), we also included both of these factors in our analyses. See Fig. S1 for estimates of the survivorship function of first names.

Results.

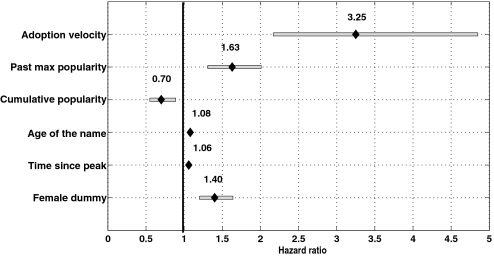

First, we examine the effects of the control variables. Fig. 2 illustrates the relationship between lifecycle dynamics and cultural abandonment (also see Tables S1 and S2 for alternate model specifications). Consistent with prior work that has shown that there is faster turnover in female names (5), the model estimations suggest that female names tend to be less persistent. The parameter estimates also suggest that cultural tastes are subject to obsolescence: Name age has a positive effect on the hazard rate. Popularity is also important: Although the cumulative popularity of a name (proportion of all births up to that point receiving that name) is associated with lower hazard rates, names that reached higher levels of popularity tend to die faster. This illustrates the dual role of popularity. Increased adoption leads to higher awareness among other potential adopters, but items that become too popular over a short time period may seem less unique, which can hurt future adoption.

Fig. 2.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from hazard rate model estimation. The regression equation is: ri(y) = exp(γXi,y−1), where ri(y) refers to the instantaneous death rate of name i in year y, Xi,y−1 is a vector of time-varying covariates, and γ is the vector of estimated coefficients. For each name i and each year y, the past peak in popularity is defined as the past year Yi,y < y at which the contribution of i to all births of the same sex, Fi,y, was maximal over all past years. The adoption velocity is defined as the rate of change in adoption in the 5 years before Yi,y: αi,y = (Fi,Yi,y−5/Fi,Yi,y)1/5 − 1, where Fi,Yi,y is the contribution of name i to all births of the same sex at the past peak in popularity. The mean of the adoption velocity is 19.5%, and the standard deviation is 0.17. The age of a name is defined as the average number of years elapsed between births with name i and the focal year, computed over all past births with name i. The cumulative popularity is the contribution of a name to all births that occurred since it entered our dataset. Popularity and cumulative popularity are normalized for the estimations. The effect of a covariate is significant if the corresponding 95% confidence interval bar does not intersect with 1.0.

More importantly, the effect of adoption velocity on cultural abandonment is strongly positive and significant: Names that experience sharper increases in popularity tend to die faster. The estimated hazard ratios imply that if a name had reached its past maximal popularity at a rate of increase 10% higher, its subsequent death rate would have been 12.5% larger. Additional analyses demonstrate the strength of this relationship (Tables S1 and S2). Because rates are compounded geometrically, even a moderate increase in the hazard rate generally implies a considerably shorter expected time until abandonment.

Our main result persists across a host of robustness checks. The effect is not simply driven by a few names that come and go very quickly (e.g., because of brief attention associated with passing celebrities). Rather, even nonextreme rates of adoption have a positive effect on the death rate (Table S1, model 4). The result also holds if alternate strategies to control for the effect of time are used (Tables S1 and S2, models 2, 3, 7–9). In addition, although using a 5-year window to compute adoption velocity allows us to use a larger portion of the available data, our main result also holds, and is in fact stronger, when longer time windows are used or when lags are introduced (Table S1, models 5 and 6). Additional analyses also show that the main result remains when other thresholds are used for defining abandonment (Table S2, model 10).

We also performed similar analyses on data from the United States. Although these data are not as comprehensive as the French data (they contain only the top 1,000 names every year for each gender), model estimations lead to similar results (Table S3).

Discussion.

These findings suggest that cultural items that experience sharper increases in adoption are less likely to persist. Even controlling for their popularity, adoption velocity was positively related to abandonment, such that first names that spiked in popularity die faster. This result is robust across a host of specifications, and across data from 2 different countries, speaking to the generalizability of the effect.

Study 2: Survey of Expecting Parents

To strengthen our suggestion that adoption velocity is driving cultural abandonment, we also examined this relationship at the individual level. Cultural abandonment is a collective outcome but relies on the aggregation of individual behavior. If sharper increases in adoption contribute to cultural decline, they should also be associated with lower attraction among individuals; parents should be less likely to adopt (give their children) names that have seen larger recent increases in usage. To test this possibility, we gave expecting parents a sample of first names and asked them how likely they would be to give each to their child. We then computed the actual adoption velocity for each name, along with its popularity, and used that to examine whether people were less interested in adopting cultural items that had recently been adopted more quickly.

In addition, we investigated whether the relationship between adoption velocity and abandonment could be caused by identity concerns. In particular, we have suggested that one reason people avoid identity-relevant cultural items that spike in popularity is that they do not want to adopt items that they believe will be short lived. To examine this possibility, we had participants rate their perception of whether each name was a fad or would be short lived. We then examined whether these perceptions drove the relationship between participants' likelihood of giving different names to their children and how quickly those names had recently been adopted.

Results.

First, analyses revealed that change in aggregate adoption predicted individual attitudes. Expecting parents reported being less likely to adopt names that had sharper recent increases in popularity (B = −0.97, SE = 0.10, P < 0.0001). This effect persisted (B = −0.31, SE = 0.13, P < 0.02) even when controlling for the recent popularity (number of births in 2006: B = −0.046, SE = 0.029, P = 0.11) as well as the overall cumulative popularity of the name (total number of births from 1880 to 2006: B = 0.31, SE = 0.027, P < 0.0001).

Second, potential adopters' distaste for high adoption velocity items was driven by longevity concerns. Names that had seen sharper recent increases in usage were more likely to be perceived as short lived (B = 2.13, SE = 0.14, P < 0.0001). Furthermore, when both longevity perceptions and actual adoption velocity were entered in a regression equation predicting adoption likelihood, longevity perception had a significant negative effect (B = −0.095, SE < 0.01, P < 0.0001), and the effect of adoption velocity was greatly reduced and no longer significant (B = −0.11, SE = 0.13, P = 0.38, Sobel z = 11.07, P < 0.0001). This suggests that the negative relation between adoption velocity and reported adoption likelihood is driven by concerns that the cultural item will be a short-lived fad.

Discussion.

These results bolster the notion that cultural items that are adopted quickly die out faster while also providing evidence for the causal mechanism behind this relationship. Expecting parents reported lower attraction to first names with a sharp recent increase in adoption. Additional analyses suggest that people avoid sharply increasing items because of symbolic concerns: Names that spiked in popularity were more likely to be perceived as short lived, or fleeting, decreasing their attractiveness to expecting parents.

General Discussion

These findings suggest that adoption velocity, or speed of adoption, may contribute to the abandonment of cultural tastes. In addition to examining the effects of popularity itself, or cumulative adoption, we have shown that cultural items that experience sharper increases in adoption tend to die out faster. Cultural items that catch on faster are more likely to be perceived as “flashes in the pan,” which can depress others' interest in adopting them.

This suggests that beliefs about the evolution of popularity may be self-fulfilling. Although no mathematical necessity forces cultural items that sharply increase in popularity to die out faster, potential adopters' beliefs have the ability to create reality. People care about symbolic value, and consequently, concerns that popularity will be fleeting can make an item less attractive. This leads people to avoid adopting it, and as a result, leads it to be short lived. Furthermore, these results suggest that individuals perceive differences in adoption velocity and that these perceptions, in turn, can influence attitudes and behavior.

One important question is how much these findings have to say about cultural decline more broadly. External factors like technological characteristics or marketing effort definitely play an important role in the dynamics of adoption and abandonment in many domains. For example, advertising might lead to fast adoption, but when advertising stops, or switches to a substitute, popularity may decline. Importantly, though, our results suggest that independently of its cause, a quick rise in popularity may have an accelerating effect on abandonment. As such, we anticipate that there will be an inherent tendency for items that have been adopted quickly to decline faster, even in cases where advertising persists.

In most empirical settings, it is difficult to parse out the relative contributions of the dynamics of popularity (e.g., adoption velocity) and other causes for abandonment (e.g., relative functional advantage or marketing effort) because these other causes are often not systematically observable. It is difficult to know how much institutional push different social movements receive or exactly how much better a new product is relative to a previous one. First names provide a context where such unobserved heterogeneity is reduced, which helps limit potential confounds. Although more work needs to be done to assess the relative contributions of external factors and internal dynamics in other domains, there is no reason to suspect that factors that drive first-name abandonment do not also play at least some role in a broader set of areas.

In addition, these findings may provide an alternate way to explain diffusion patterns that are traditionally seen as driven by saturation. Diffusion models typically assume that adoption decelerates because there is a fixed population of potential adopters (6, 9). This explanation, however, makes less sense in the context of names. New babies are born each year, and consequently, the set of potential name-adopters is continuously renewed. The fact that the adoption of a given name declines, even when the supply of adopters is potentially infinite, suggests that other factors (beyond saturation) must be involved. Adoption velocity is one such factor, and this sheds light on why cultural items are abandoned, or their adoption halted, even when there is no hard bound on the number of adopters. These results suggest it may be worth reconsidering some prior outcomes that the literature has interpreted as the outcome of saturation, because similar patterns can result from meaning change.

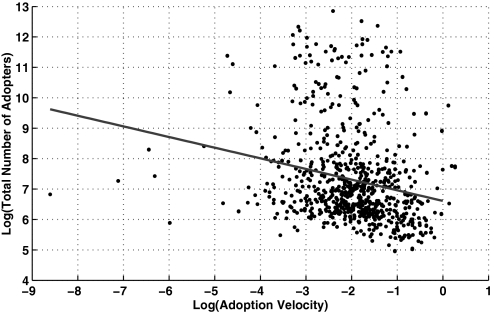

Might items that are adopted more quickly also realize reduced overall success (i.e., cumulative adoption)? Although we are not aware of any prior empirical work that has examined this relationship, conventional wisdom [and some prior theorizing (30)] would suggest that faster adoption should improve success. Diffusion and word of mouth increase with the number of adopters (6). If a social movement is adopted more quickly over a particular period, there are more people to talk about it. This should accelerate the diffusion process and increase awareness among the rest of the population, potentially increasing the number of people who will eventually join. It should also boost social proof (31) and increase others' likelihood of adoption. Further analyses of the French name data, however, indicate the opposite: Names with faster adoption actually ended up being adopted by fewer people (Fig. 3 and Table S4). Estimation of the effect of adoption velocity on the cumulative number of births with a given name before abandonment show that adoption velocity has a negative effect on the cumulative number of adopters, even after controlling for other factors such as the age of a name, or the time elapsed since the occurrence of the peak in popularity (Table S4, Models 1–5).

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot and line of best fit (by OLS) of the logarithm of the cumulative number of adopters until abandonment and the logarithm of adoption velocity before peak. First names with high adoption velocity tend to have fewer adopters overall.

The same result appears in the U.S. data. Similar outcomes have also been noted in the music industry, where new artists who shoot to the top of the charts right away, rather than growing slowly, realize overall lower sales (32). This seemingly counterintuitive finding has important implications. It suggests that faster adoption is not only linked to faster death but may also hurt overall success.

It is important to note that negative effects of adoption velocity (and popularity itself) on the cultural life span should be more likely in symbolic domains. Although some domains are often used to communicate identity (e.g., cars, clothes, and names) others are not usually seen as identity relevant [e.g., refrigerators or books (18, 20)]. Negative effects of adoption velocity should occur only in situations where choice is seen as a signal, or marker, of identity and where rapidly adopted cultural items may be stigmatized. In other domains, fast adoption may even be seen as a positive and may increase further adoption (30). Negative effects of adoption velocity may also be more likely when there are high costs of abandonment at the individual level. Although it is relatively trivial to stop wearing a wristband or stop listening to a certain song, it is much more difficult to rename a child or buy a new car. As a result, people may be more hesitant to adopt rapidly increasing cultural items in domains where taste change is more difficult, costly, or effortful.

By examining the abandonment of cultural tastes, these findings also contribute to the burgeoning literature on cultural dynamics (8). Although cross-cultural research has investigated how cultural background can influence attention, perception, and cognition (33), researchers have also begun to examine the reciprocal process, or how psychological processes shape culture (7). Whether cultural tastes succeed or fail depends on their fit with human memory, emotion, and social interaction. By more closely examining the psychological processes behind individual choice and cultural transmission, deeper insight can be gained into the relationship between individual (micro) behavior and collective (macro) outcomes such as cultural success (1, 34).

Taken together, our results provide evidence for a backlash against things that are adopted too quickly. Social influence not only affects behavior through popularity but also through the rate of change in adoption. People may avoid music artists that spike in popularity, and too many dissertations around a similar topic may lead other scientists to avoid the area because of concerns about its longevity. This has important implications for people who want to ensure the persistence and success of particular items. Scholars interested in developing a new area, for example, may want to encourage others to join but at a slow and steady pace. Shepherding a consistent flow of new adopters should help pave the way for persistence and success. Things that catch on too quickly may die out just as fast.

Materials and Methods

Study 1. French Data.

We acquired data on the number of children born in France with each name each year from the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE). For each unique first name, the data records the number of male and female births that were officially declared each year from 1900 to 2004.

The ability to discern name life cycles is necessarily limited by the available data. The data ends at a fixed point in time, making it impossible to say for sure whether a name has been permanently abandoned. Besides, some names may lay dormant for decades only to be revived. We therefore define the “abandonment” of a name with respect to its past evolution: A name is considered abandoned when its adoption declines to a low level relative to its history. This takes advantage of the fact that most names have a single peak in popularity, and once they start declining, they do so consistently (at least until they are revived decades later).

Because we are interested in abandonment, we focus on names that achieve at least some usage. Unless otherwise noted, our analyses focus on name evolution after the first year in which they have reached at least 30 births (in which case we say that the name becomes “at risk” of being abandoned). We chose this level because we have data for names that have at least 3 births per year. This ensures that all of the included names have decreased below 10% of their peak in popularity when they drop out of the dataset. In addition, given our interest in understanding the relationship between past evolution and abandonment and the fact that we are unable to observe patterns of adoption before 1900, we include only names that appear to be “born” after that year (i.e., have zero births in 1900). Finally, because we calculate the rate of change in popularity over the past 5 years, we include only names that appear in the dataset for at least 6 years in a row. Our dataset includes all 2,570 (1,132 male names and 1,438 female names) names that meet these criteria.

U.S. Data.

We performed similar analyses on name popularity in the United States using data from the U.S. Social Security Administration. These data are not as comprehensive because they contain only the top 1,000 names every year. Consequently, the threshold for inclusion varies over time and can be quite high (e.g., the least popular name listed in 2006 received 185 births). To avoid estimation problems associated with these inclusion issues, we considered only names that ever received at least 1,850 births in a given year (10 times the number of births of the least-popular name listed in the last year of observations) and were in the Social Security Administration dataset for at least 6 consecutive years.

Study 2.

Six hundred sixty-one Americans who were expecting children (mean age = 31) voluntarily completed a Baby Names study online. They were shown 30 different male and female baby names and asked to rate how likely they would be to give each name to their child (1 = Not at all likely, 7 = Extremely likely). They were not shown any popularity information, just the names themselves. They were then shown the same set of names and asked to rate how likely they thought each name would be a short-lived fad (1 = Not at all likely, 7 = Extremely likely). Finally they completed some demographic measures (e.g., age, gender, etc.) including the sex of their child if they knew it. There were 90 names overall, but to avoid participant fatigue, each participant rated only 30 names. We focused on expecting parents because we are interested in how adoption velocity affects real naming decisions, not just name perceptions among the general population. To this end, we examined ratings of both genders of names for participants who did not yet know the sex of their child, and only ratings of gender-consistent names for expecting parents who already knew their future child's gender. Results are similar, however, when all ratings are used. To avoid order effects, names were presented in random order across participants.

Fixed-effects panel linear regressions were used to examine the relationship between survey ratings and characteristics of the past evolution of name popularity. For each name, we obtained the number of births in 2006, the cumulative number of births with that the name between 1880 and 2006, and the average rate of change in the number of the births with that name between 2001 and 2006. If the name was not recorded in the dataset in 2001 (it was not among the top 1,000 names in that year), we calculated the rate of change using a similar metric for the years in which it had been in the data.

Cumulative Adoption.

We examined the relationship between adoption velocity and the total number of births received by a given first name using the French names dataset. The U.S. data revealed similar results. The fit is slightly better when the log is used, but we find the same results without taking the log. Table S4 presents results of OLS estimations of linear regressions of the logarithm of the total number of births in the French data. Only names for which the death event is observed are included in the analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Eric Bradlow, Glenn Carroll, Jerker Denrell, James Fowler, Jacob Goldenberg, Sasha Goodman, Mike Hannan, Balázs Kovács, Chip Heath, Wes Hutchinson, Elihu Katz, William Labov, Giacomo Negro, Don Lehmann, Stanley Lieberson, Noah Mark, Winter Mason, Huggy Rao, Matt Salganik, Aner Sela, Christophe Van den Bulte, Duncan Watts, Scott Wiltermuth, and seminar participants at Stanford Graduate School of Business and Yahoo! Research for comments of prior versions of the research and Young Lee and Laura Wattenberg for help with Study 2. This work was supported in part by the Stanford Graduate School of Business Interdisciplinary Behavioral Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0812647106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Salganik MJ, Dodds PS, Watts DJ. Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science. 2006;311:854–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1121066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger J, Heath C. Idea habitats: How the prevalence of environmental cues influences the success of ideas. Cognit Sci. 2005;29:195–221. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog0000_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW. Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberson S. A Matter of Taste: How Names, Fashions, and Culture Change. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bass FM. A new product growth model for consumer durables. Manage Sci. 1969;15:215–227. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaller M, Crandall CS. The Psychological Foundations of Culture. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashima Y. A social psychology of cultural dynamics: Examining how cultures are formed, maintained, and transformed. Social Person Psychol Compass. 2008;2:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martindale C. The Clockwork Muse. New York: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesendorfer W. Design innovation and fashion cycles. Am Econ Rev. 1995;85:771–792. [Google Scholar]

- 12.White HC. Chains of Opportunity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyersohn R, Katz E. Notes on a natural history of fads. Am J Sociol. 1957;62:594–601. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberson S, Lynn FB. Popularity as a Taste: An application to the naming. process. Onoma. 2003;38:235–276. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibenstein H. Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers' demand. Q J Econ. 1950;64:183–207. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder CR, Fromkin HL. Uniqueness. New York: Plenum; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsee CK, Abelson RP. The velocity relation: Satisfaction as a function of the first derivative of outcome over time. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:341–347. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shavitt S. The role of attitude objects in attitude functions. J Exp Psych. 1990;26:124–148. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy SJ. Symbols for sale. Harvard Bus Rev. 1959;33:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger J, Heath C. Where consumers diverge from others: Identity-Signaling and product domains. J Consumer Res. 2007;34:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmel G. Fashion. Am J Sociol. 1957;62:541–548. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger J, Rand L. Shifting signals to help health: Using identity-signaling to reduce risky health behaviors. J Consumer Res. 2008;35:509–518. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger J, Heath C. Who drives divergence? Identity signaling, outgroup dissimilarity, and the abandonment of cultural tastes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:593–607. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieberson S, Dumais S, Baumann S. The instability of androgynous names: The symbolic maintenance of gender boundaries. Am J Sociol. 2000;105:1249–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sue CA, Telles EE. Assimilation and gender in naming. Am J Sociol. 2007;112:1383–1415. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fryer RG, Jr, Levitt SD. The causes and consequences of distinctively black names. Q J Econ. 2004:767–805. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bentley RA, Hahn MW, Shennan JC. Random drift and culture change. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2004;271:1443. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blossfeld H, Rohwer G. Techniques of Event History Modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acker M, McReynolds P. The “need for novelty”: A comparison of six instruments. Psych Record. 1967;17:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Vany A. Hollywood Economics. New York: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cialdini RB. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayfield G, Caufield K. Developing Artists: A Billboard White Paper. New York: Nielsen Business Media; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nisbett RE, Masuda T. Culture and point of view. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11163–11170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934527100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman JS. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.