Abstract

In conventional αβ T cells, the Tec family tyrosine kinase Itk is required for signaling downstream of the T cell receptor (TCR). Itk also regulates αβ T cell development, lineage commitment, and effector function. A well established feature of Itk−/− mice is their inability to generate T helper type 2 (Th2) responses that produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13; yet these mice have spontaneously elevated levels of serum IgE and increased numbers of germinal center B cells. Here we show that the source of this phenotype is γδ T cells, as normal IgE levels are observed in Itk−/−Tcrd−/− mice. When stimulated through the γδ TCR, Itk−/− γδ T cells produce high levels of Th2 cytokines, but diminished IFNγ. In addition, activated Itk−/− γδ T cells up-regulate costimulatory molecules important for B cell help, suggesting that they may directly promote B cell activation and Ig class switching. Furthermore, we find that γδ T cells numbers are increased in Itk−/− mice, most notably the Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ subset that represents the dominant population of γδ NKT cells. Itk−/− γδ NKT cells also have increased expression of PLZF, a transcription factor required for αβ NKT cells, indicating a common molecular program between αβ and γδ NKT cell lineages. Together, these data indicate that Itk signaling regulates γδ T cell lineage development and effector function and is required to control IgE production in vivo.

Keywords: T cell development, T cell differentiation, T cell signaling

The Tec family tyrosine kinase Itk is important for signaling downstream of the T cell receptor (1). In particular, Itk-deficient T cells have defects in phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ) phosphorylation, calcium mobilization, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) activation, and AP-1 and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) activation after T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. Itk is also critical for conventional αβ T cell development, selection, and function. Of particular importance, Itk signaling regulates CD4+ T helper cell differentiation, playing a key role in the development of Th2 responses (2). Based on this well-documented defect of Itk−/− mice in generating Th2 effector responses and cytokine production, it was surprising to discover that these mice had spontaneously elevated levels of serum IgE (3, 4), as B cell isotype switching to IgE is highly dependent on Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 (5). As our previous studies had indicated that Itk−/− αβ TCR+ NKT cells (referred to as αβ NKT cells) were also highly defective in producing effector cytokines such as IL-4 (6), we considered the possibility that γδ TCR+ NKT cells were the major source of Th2 cytokines in Itk−/− mice.

The γδ T cells are a highly conserved subset of T cells that constitutes 1–5% of the lymphocytes in the blood and peripheral organs of mice but can account for up to 50% of the lymphocytes in the mucosal epithelia. As with other subsets of “innate” T cells, γδ T cells express memory cell surface markers (7), and are capable of rapidly secreting effector cytokines (8). Among the many functions attributed to γδ T cells, a great deal of recent interest has focused on their ability to modulate adaptive immune responses, specifically the humoral response (9).

A variety of studies have indicated that γδ T cells are able to provide help for B cell responses. Initial studies performed in mice lacking αβ T cells showed that B cell expansion, differentiation, and secretion of ‘T-dependent’ antibody isotypes, IgE, and IgG1, were all intact in these mice (10). Furthermore, TCRβ−/− mice challenged repeatedly with parasitic infections could produce germinal centers and generate increased antibody production (11). Using a model of pulmonary allergic inflammation, decreased production of IgE and IgG1 was seen in mice lacking γδ T cells compared with WT mice (12). The γδ T cells have also been shown to directly induce germinal center formation and Ig hypermutation (13). Interestingly, even though the γδ T cells expressing CD4 account for only 5–10% of all γδ cells, it is this subset that appears to be responsible for inducing germinal centers (14). Human γδ T cells have also been found in germinal centers; these cells were found to up-regulate B cell costimulatory molecules such as CD40L, OX40, CD70, and inducible costimulatory molecule (ICOS) in response to TCR stimulation (15, 16). Together, these data indicate that γδ T cells can promote, either directly or indirectly, the humoral immune response.

Here we show that, in the absence of Itk, γδ T cell differentiation and effector function are dramatically altered. Itk−/− mice contain increased numbers of CD4+ and NK1.1+ γδ T cells that normally constitute the γδ NKT population (17). These cells express PLZF, a transcription factor that uniquely defines αβ NKT cells and is essential for normal αβ NKT cell development (18, 19). As a consequence, Itk−/− γδ T cells produce robust amounts of Th2 cytokines when stimulated, accompanied by enhanced expression of cell surface receptors associated with B cell help, such as ICOS and CD40L and thus promote a spontaneous elevation in serum IgE levels. These data indicate a surprising role for Itk in regulating the lineage development and effector function of γδ T cells, particularly in controlling the PLZF+ subset.

Results

γδ T Cells Promote the Hyper IgE and Enriched Germinal Center Phenotype Seen in Itk−/− Mice.

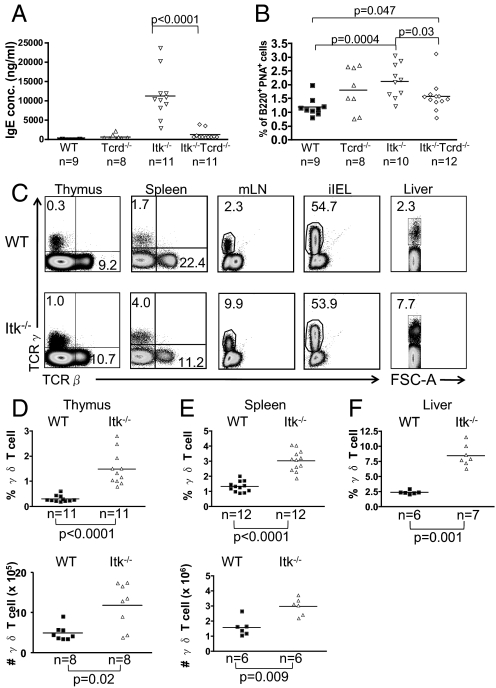

In an effort to identify the cell type producing Th2 cytokines and driving IgE class-switching and secretion in unimmunized Itk−/− mice, we considered γδ T cells. To test this possibility, Itk−/− mice were crossed to Tcrd−/− mice (20) that lack γδ T cells. As shown in Fig. 1A and reported previously (3, 4), Itk−/− mice have elevated concentrations of serum IgE compared with WT controls. Strikingly, in Itk−/−Tcrd−/− double-deficient mice, serum IgE levels drop significantly compared with Itk−/− mice. Similar results were seen upon analysis of the proportion of germinal center phenotype B cells (B220+ peanut agglutinin [PNA]+) (Fig. 1B). Individual cohorts of mice were tested at 2 months of age, 3.5 months of age, and 5 months of age, with similar results.

Fig. 1.

γδ T cells in Itk−/− mice are responsible for the spontaneous elevation in serum IgE levels. (A) Serum obtained from WT, Tcrd−/−, Itk−/−, and Itk−/−Tcrd−/− mice were analyzed for IgE by ELISA. (B) Splenocytes from WT, Tcrd−/−, Itk−/−, and Itk−/−Tcrd−/− mice were stained with α-B220 Ab and PNA to identify germinal center B cells. Differences between WT and Tcrd−/− (P = 0.14) and between Itk−/− and Itk−/−Tcrd−/− (P = 0.54) were not statistically significant. (C) Cells were prepared from thymus, spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN), intestinal epithelium (iIELs), and liver and were stained with anti-TCRδ and anti-TCRβ Abs. (D–F) Percentages and absolute numbers of γδ T cells were compiled for the thymus (D) and spleen (E); percentages only were compiled for liver (F).

Itk-Deficient Mice Have Increased Numbers of γδ T Cells.

The finding that elevated serum IgE levels in Itk−/− mice were dependent on γδ T cells suggested that the γδ T cells present in Itk−/− mice might be altered relative to their WT counterparts. We first examined γδ T cell numbers. As seen in Fig. 1C, Itk−/− mice have increased proportions of γδ T cells in the thymus, the spleen, the mesenteric lymph nodes, and the liver, but not in the intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte (iIEL) compartment. A summary of data indicates significant increases in the proportion and absolute numbers of γδ T cells in both the thymus and the spleen, as well as an increase in the percentage of γδ T cells in the liver, in the absence of Itk (Fig. 1 D–F).

Itk−/− Mice Contain Increased Proportions of γδ T Cells Subsets Expressing Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+, CD4, and NK1.1.

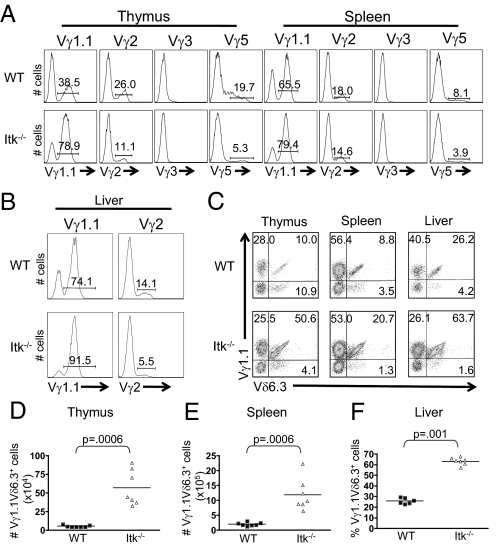

Analysis of TCRγ chain repertoires indicated an increased proportion in Vγ1.1+ γδ T cells in Itk-deficient versus WT mice, and a concomitant decrease in the other major subsets (Vγ2+ and Vγ5+) (Fig. 2 A and B). Further, the majority of Vγ1.1+ γδ T cells in the thymus and liver of Itk−/− mice also expressed Vδ6.3 (Fig. 2C). Overall, we find a significant increase in the absolute numbers of this γδ T cell subset in thymus and spleen of Itk−/− mice compared with controls (Fig. 2 D and E), as well as an increased proportion of Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells in Itk−/− liver (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells are the predominant subset of γδ NKT cells, and readily produce effector cytokines (17, 21, 22).

Fig. 2.

Itk−/− mice have an increased population of Vγ1.1Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells. (A) Thymocytes and splenocytes were stained with antibodies to TCRδ and either Vγ1.1, Vγ2, Vγ3, and Vγ5. Histograms show Vγ staining on gated TCRδ+ cells. (B) Lymphocytes were isolated from the liver and stained with antibodies to TCRδ and Vγ1.1 or Vγ2. Histograms show Vγ staining on gated TCRδ+ cells. (C) Thymocytes, splenocytes, and liver cells were stained with antibodies to TCRδ, Vγ1.1 and Vδ6.3. Dot plots show Vγ1.1 vs. Vδ6.3 staining on gated TCRδ+ T cells. (D) Absolute numbers of Vγ1.1Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells in the thymus and spleen and percentages of Vγ1.1Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells in the liver were compiled.

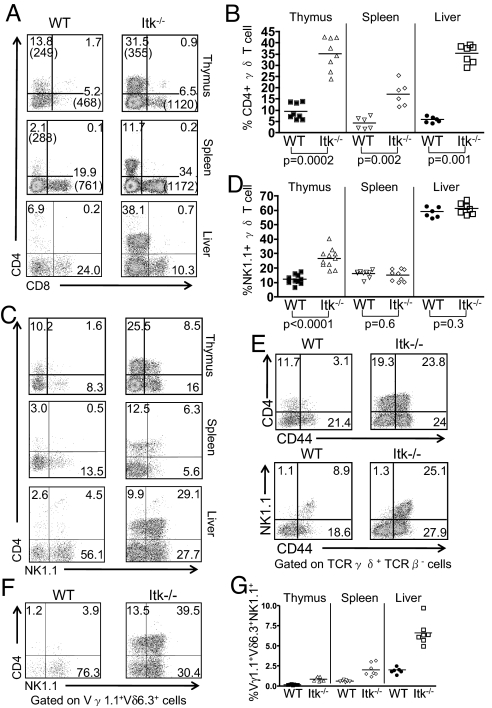

In contrast to WT γδ T cells, the Itk−/− γδ T cell population shows a striking increase in the proportion of CD4+ cells in the thymus, spleen and liver (Fig. 3 A and B). Itk−/− mice also had elevated proportions of thymic NK1.1+ γδ T cells (Fig. 3 C and D). Interestingly, the majority of the thymic Itk−/− CD4+ γδ T cells and virtually all of the thymic Itk−/− NK1.1+ γδ T cells express high levels of the memory cell marker CD44 (Fig. 3E), as well as the activation marker CD69. As previously reported, the majority of γδ T cells in the liver of WT mice are NK1.1+ (i.e., γδ NKT cells) (17), and this is also the case in Itk−/− liver (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

Altered γδ T cell subsets in the spleen and thymus of Itk−/− mice. Cells were prepared from thymus, spleen, and liver of WT and Itk−/− mice and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) CD4 vs. CD8 expression on gated TCRδ+TCRβ− cells. The percentages of each subpopulation are indicated, and the mean fluorescence intensities are shown in parentheses. (B) The percentages of CD4+TCRδ+ cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver are shown. (C) CD4 vs. NK1.1 expression on gated TCRδ+TCRβ− cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver. (D) The percentages of NK1.1+TCRδ+ cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver. (E) Thymic TCRδ+TCRβ− cells were analyzed for CD44 vs. CD4 (top) or NK1.1 (bottom) expression. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (F) TCRδ+TCRβ− cells from the liver were analyzed for Vγ1.1, Vδ6.3, NK1.1, and CD4 expression. Dot-plots show NK1.1 vs. CD4 expression on gated Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ cells. (G) The percentages of total cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver that represent the Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+NK1.1+ subset were calculated. Differences between the WT and Itk−/− were statistically significant (thymus, P = 0.0006; spleen, P = 0.0006; liver, P = 0.001).

Focusing on the Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ subset of γδ T cells, we find that WT and Itk−/− mice each have a similar proportion of NK1.1+ CD4− cells, whereas NK1.1+ CD4+ cells are increased substantially in Itk−/− mice [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Furthermore, outside the thymus, the Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ subset is found predominantly in the liver, rather than the spleen (Fig. 3 F and G), as has been reported previously for γδ NKT cells (17). The γδ T cells not expressing Vγ1.1Vδ6.3 correspond to the “conventional” NK1.1−CD4−CD8− subset; this conventional γδ T cell subset is not altered in numbers in Itk−/− versus WT mice, indicating that ITK controls the generation of “nonconventional” CD4+ or NK1.1+, but not conventional, γδ T cells.

Expanded populations of CD4+ γδ T cells have been previously demonstrated in mice lacking expression of both TCRβ and CD5 (14). We therefore examined CD5 expression on Itk−/− γδ T cells, to determine if altered levels of CD5 might be contributing to the increased number of CD4+ γδ T cells in these mice, but detected no differences between WT and Itk−/− mice. However, like a previously-reported subset of activated γδ T cells specific for self-ligands, the MHC class Ib molecules, T10/T22 (23), the NK1.1+ subset of thymic Itk−/− γδ T cells are all CD122-positive.

To determine whether the alterations we observed in Itk−/− mice are intrinsic to the hematopoietic cells or to the environment, we generated bone marrow chimeras using WT or Itk−/− bone marrow cells. These experiments demonstrated that the increased proportions of both γδ T cells and germinal center B cells seen in Itk−/− mice are intrinsic to Itk−/− hematopoietic cells (Fig. S2). Consistent with these data, we also find that the predominant Tec kinase expressed in WT γδ T cells is Itk (Fig. S3).

Enhanced Expression of IL-4 and PLZF in Itk-Deficient γδ T Cells.

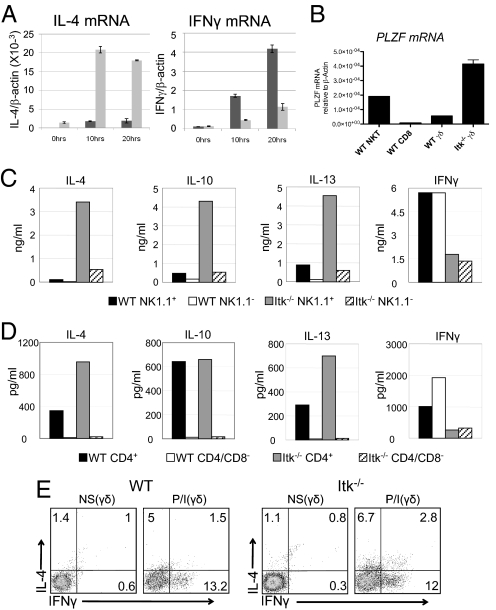

To determine the basis for the altered function of Itk−/− γδ T cells, we examined mRNA levels for T-bet, Eomesodermin, and GATA-3 in WT versus Itk−/− γδ T cells. We found that Itk−/− γδ T cells consistently expressed higher levels of GATA-3 mRNA and protein compared with WT γδ T cells, while the NK1.1− subset of Itk−/− γδ T cells have reduced levels of mRNA for both T-bet and Eomesodermin (Fig. S3). These findings suggested that Itk−/− γδ T cells might produce a distinct pattern of cytokines compared with WT γδ T cells. We first examined mRNA levels for the signature cytokines, IL-4 and IFNγ, after γδ T cell activation in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4A, in response to γδ TCR stimulation, Itk−/− γδ T cells had constitutively elevated levels of IL-4 mRNA before stimulation and exhibited dramatically enhanced induction of IL-4 mRNA at 10 hours and 20 hours poststimulation compared with WT γδ T cells. Basal levels of IFNγ mRNA were similar between the WT and Itk−/− γδ T cells; after stimulation, both cell types produced IFNγ, although WT γδ T cells showed higher levels of IFNγ mRNA compared with γδ T cells lacking Itk.

Fig. 4.

Itk−/− γδ T cells produce IL-4 plus IFN-γ and express the transcription factor PLZF. Lymph nodes and spleens from WT and Itk−/− mice were pooled, and total TCRγδ+ cells (A, B) or sorted subpopulations (C, D) were analyzed. (A) 2 × 105 cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of anti-TCRδ for 0, 10, and 20 hours. IL-4 (left panel) and IFNγ (right panel) mRNA expression levels normalized to β-actin were determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Levels of PLZF mRNA normalized to β-actin were determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. WT peripheral CD8+ αβ T cells and αβ NKT cells were analyzed for comparison. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (C) 5 × 104 cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of anti-TCRδ for 72 hours and supernatants were analyzed for the presence of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IFNγ by cytometric bead array (CBA). Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) 3 × 104 cells were stimulated as in (B). Supernatants were analyzed for the presence of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IFNγ by CBA. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (E) Nonstimulated (NS) and stimulated (P/I) WT (left) and Itk−/− (right) γδ T cells were analyzed for intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ production. Cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml PMA and 2 μg/ml Ionomycin (P/I) for 4 hours. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

Based on the high proportion of Vγ1.1+Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells present in Itk−/− mice and the previous association of this γδ T cell subset with dual production of IL-4 and IFNγ (21, 22), we also examined WT and Itk−/− γδ T cells for expression of the transcription factor PLZF. PLZF has recently been found to be critical for the development and effector function of TCRαβ+ NKT cells, where it promotes the simultaneous production of IL-4 and IFNγ (18, 19). Interestingly, we found that splenic Itk−/− γδ T cells express substantially higher amounts of PLZF mRNA than do WT γδ T cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, among Itk−/− γδ T cells, the NK1.1+ fraction expresses particularly high levels of PLZF mRNA. These findings support the conclusion that γδ T cell development is altered in the absence of Itk.

To assess levels of cytokine protein secretion, individual subsets of Itk−/− and WT γδ T cells were purified and stimulated. As previous studies have found that NK1.1+ γδ T cells and CD4+ γδ T cells produce the highest levels of cytokines, particularly “Th2” cytokines (24–28), we compared NK1.1+ to NK1.1−, and CD4+ to CD4− γδ T cell subsets. After 72 hours of stimulation, WT NK1.1+ γδ T cells secreted more IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 than their NK1.1− counterparts; in contrast, both NK1.1+ and NK1.1− subsets of WT γδ T cells secreted large amounts of IFNγ (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the analysis of cytokine mRNA levels, we observed elevated secretion of the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 by the Itk−/− NK1.1+ γδ T cells when compared with WT NK1.1+ cells; furthermore, Itk−/− NK1.1+ γδ T cells secreted much higher amounts of these cytokines per cell relative to the Itk−/− NK1.1− subset. In addition, we found that both subsets of Itk−/− γδ T cells secreted IFNγ, but at a lower level than the WT cells.

Comparison of the CD4+ versus CD4− subsets of γδ T cells confirmed previous data (27, 28) that γδ T cells expressing CD4 are the major cytokine-producing population, particularly for the “Th2” cytokines. As shown in Fig. 4D, Itk−/− CD4+ γδ T cells produce elevated levels of IL-4 and IL-13 compared with WT CD4+ γδ T cells, but produce similar levels of IL-10. None of these cytokines were detected in supernatants of stimulated CD4− γδ T cells from either Itk−/− or WT mice. As noted above, WT γδ T cells (both CD4+ and CD4− subsets) secrete higher levels of INFγ than Itk−/− γδ T cells.

On a population basis, Itk−/− γδ T cells secreted both IL-4 and IFNγ after stimulation. To determine whether individual cells were dual producers of both effector cytokines, we stimulated WT and Itk−/− γδ T cells in vitro with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin and then examined IL-4 and IFNγ production by intracellular cytokine staining (Fig. 4E). As expected, a larger proportion of WT γδ T cells produce IFNγ in response to stimulation compared with those that produce IL-4, and few cells produce both cytokines. In contrast, Itk−/− γδ T cells include a significantly larger population that produces IL-4 than is seen in the WT γδ T cell subset (Itk−/−, 6.9 ± 1.1; WT, 3.5 ± 0.8; n = 7; P = 0.04); additionally, a greater proportion of Itk−/− γδ T cells produces both IL-4 plus IFNγ compared with WT γδ T cells (Itk−/−, 3.9 ± 0.8; WT, 1.7 ± 0.3; n = 7; P = 0.02). Because this pharmacological stimulation bypasses the need for ITK in TCR-mediated signaling, these data indicate that a larger proportion of Itk−/− γδ T cells are programmed to produce IL-4, as well as IL-4 plus IFNγ, before their activation. This latter finding, together with the data demonstrating increased numbers of CD4+ and NK1.1+ γδ T cells in the Itk−/− mice, strongly suggests that γδ T cell development is altered in the absence of Itk leading to a striking increase in a PLZF-positive, IL-4-producing γδ T cell population.

Itk−/− γδ T Cells Up-Regulate Surface Receptors That Promote B Cell Help.

We next examined γδ T cells for the expression of co-stimulatory molecules that provide B cell help, such as CD40L, CD70, OX40, and ICOS (15). For these experiments, WT and Itk−/− thymocytes and splenocytes were evaluated directly ex vivo and, in addition, were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of stimulatory anti-TCRδ antibodies. Although analysis of splenic γδ T cells from WT and Itk−/− mice did not reveal any major changes in co-stimulatory markers, we did see a small increase in the proportion of constitutively ICOS-positive γδ T cells in the spleens of Itk−/− mice. Inasmuch as Itk−/− mice have a two-fold increase in the absolute number of total γδ T cells in the spleen compared with WT, this difference amounts to a ≈10-fold increase in ICOS-positive splenic γδ T cells, and thus could account for the enhanced B cell activation observed in Itk−/− mice.

More strikingly, levels of ICOS were increased on a large proportion of the thymic Itk−/− γδ T cells compared with controls, but remained unaltered following stimulation (Fig. 5A). Evaluation of the ICOShi fraction of Itk−/− thymic γδ T cells indicated that nearly all of these cells were CD4+, and a substantial proportion were also NK1.1+ (Fig. 5B). Little to no difference was seen in the basal levels of CD40L and OX40 when comparing thymic Itk−/− γδ T cells to WT γδ T cells directly ex vivo (Fig. 5A). However, after 24 hours of in vitro stimulation on anti-TCRδ–coated plates, Itk−/− cells up-regulated both CD40L and OX40, whereas WT γδ T cells did not. This up-regulation of CD40L and OX40 was detected on all subsets of Itk−/− γδ T cells (Fig. 5B). Finally, we could not detect expression of CD70 on either WT or Itk−/− thymic γδ T cells.

Fig. 5.

Itk−/− γδ T cells up-regulate costimulatory molecules involved in B cell help. (A) Thymocytes from WT and Itk−/− mice were pooled and left nonstimulated (0 hours) or were stimulated with 10 μg/ml α-TCRδ for 24 hours. Nonstimulated and stimulated TCRδ+TCRβ− T cells were then analyzed for the expression of ICOS, CD40L, and OX40. (B) WT and Itk−/− thymocytes stimulated for 24 hours with 10 μg/ml α-TCRδ antibodies were stained for CD4, ICOS, CD40L, OX40, and NK1.1 expression.

Discussion

Overall, our data indicate that γδ T cell development is significantly altered in the absence of Itk, yielding increased numbers of γδ T cells and a shift in the major effector functions mediated by these cells. Most strikingly, Itk−/− mice have elevated numbers of γδ T cells expressing CD4 and NK1.1. Furthermore, unlike the γδ T cells in WT mice, the Itk−/− γδ T cells secrete large quantities of the Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-10, and IL13, in addition to the IFNγ typically secreted by activated WT γδ T cells, correlating with high levels of the transcription factor, PLZF. These findings strongly suggest that Itk signaling plays a key role in regulating γδ T cell lineage development.

Surprisingly, these altered γδ T cells are responsible for promoting significant levels of spontaneous IgE secretion in Itk−/− mice. Based on the findings presented here, it is likely that the high levels of IL-4 and IL-13 produced by the activated Itk−/− γδ T cells are a major factor in this response. Our data indicate that activated Itk−/− γδ T cells express elevated amounts of B cell co-stimulatory molecules, such as ICOS, CD40L, and OX40, further suggesting that the γδ T cells may be directly providing help to the B cells, leading to B cell activation and Ig class switching.

In humans, a variety of studies have implicated γδ T cells in allergic airway inflammation (29, 30) and, specifically, in promoting B cell activation and IgE class switching (31, 32). One interesting clinical report found that IL-4-producing γδ T cells were likely responsible for a case of hyper IgE syndrome (33). Studies performed in vitro with human γδ T cells showed that these cells, in combination with IL-4, can induce B cell activation, Ig isotype switching, and secretion of IgE (34). Further, these findings correlate well with observations that human γδ T cells can express ICOS, CD40L, OX40, and CD70 (15). Our data indicate that the Tec family tyrosine kinase, Itk, plays a key role in regulating this potentially highly detrimental function of γδ T cells.

Recently, γδ T cells have also been implicated in the elevated IgE concentrations seen in mice carrying mutations in additional T cell signaling proteins. For instance, in the absence of the E3-ubiquitin ligase, Itch, γδ T cells secrete IL-4 and promote IgE production in nonimmunized mice (29). More strikingly, mice expressing a mutant allele of the adapter protein linker of activated T cells (LAT), which lacks the three c-terminal tyrosines, succumb to a fatal lymphoproliferative disorder that is mediated by γδ T cells (35). In these LAT mutant mice, the γδ T cells accumulate to large numbers, and show a phenotype remarkably similar to those lacking Itk. For instance, the LAT mutant γδ T cells secrete IL-4, rather than IFN-γ, and many of them express the CD4 co-receptor; in addition, the mice also have elevated levels of serum IgE. As this mutant LAT protein does not support αβ T cell development, these altered γδ T cells are the only source of T cell help for B cell activation and IgE class switching. As Itk and LAT interact in a TCR-dependent signaling complex in αβ T cells, the similarities in the γδ T cell phenotype in these two lines of mice strongly suggest that these proteins are also in the same signaling pathway downstream of the γδ TCR, and furthermore, that this pathway regulates the development and effector function of γδ T cells. As Itk has previously been shown to suppress the development of innate αβ lineage T cells and to promote the development of conventional αβ T cells (36), a similar function for Itk may be required in γδ T cells; thus, in the absence of Itk, enhanced development of innate (e.g., PLZF+, NK1.1+) γδ T cells occurs, leading to increased numbers of effector cytokine-producing γδ T cells in Itk−/− mice.

Interestingly, a recent report by Jensen et al. demonstrates that γδ T cells, like αβ T cells, are found as both naïve and effector subsets (23). Effector-type γδ T cells express higher levels of CD44, NK1.1, and CD122 relative to the naïve subset and in addition, show an altered cytokine secretion profile. Furthermore, the presence of the effector γδ T cell population correlated with the expression of the TCR ligand for these γδ T cells, indicating that ligand recognition was responsible for their activated phenotype. As a large population of Itk−/− γδ T cells exhibit a similar effector cell phenotype and produce effector cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-4; these findings suggest that ligand recognition by Itk−/− γδ T cells may contribute to their activation in vivo and their role in promoting IgE production in nonimmunized mice.

These findings have substantial relevance to the potential effects of small molecule inhibitors of Itk. Given the importance of Itk in Th2 development and cytokine production by CD4+ αβ T cells, this kinase is currently being targeted for the development of drugs to treat asthma and other allergic diseases (5, 37). It would be unfortunate if Itk inhibition also led to the aberrant activation of γδ T cells and thus to enhanced production of IgE. Elevated levels of serum IgE would, in turn, lead to up-regulation of the FcεRI on mast cells (38), promoting hyperresponsiveness of these cells to IgE-mediated receptor aggregation. In light of the findings presented here, further studies on the role of Itk in human γδ T cells are clearly warranted.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Itk−/− mice (39) are on the C57BL/10 strain. Tcrd−/− mice (20) on the B57BL/6 background (Jackson Laboratories) were crossed to Itk−/− mice to obtain Itk−/−Tcrd−/− mice. Wild-type mice were Itk+/−Tcrd+/− littermates or C57BL/10 mice (Jackson Laboratories). All mice used were 2–3 months of age and were maintained at the University of Massachusetts Medical School under specific pathogen-free conditions after institutional animal care and use committee approval.

Cell Preparations, Antibodies, and Flow Cytometry.

Liver lymphocytes were isolated by collagenase digestion of minced liver followed by Ficoll gradient centrifugation; iIELs were isolated by incubation of cleaned intenstine followed by Ficoll gradient centrifugation. The following antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen: TCRδ(GL3)-FITC, Vγ2-FITC, Vγ3-FITC, Vδ6.2/6.3-PE, TCRβ-allophycocyanin, TCRβ-PE, TCRβ-biotin (bio), CD4-allophycocyanin, CD4-PE, CD8α-PerCP-Cy5.5, NK1.1-PE-Cy7, CD5-CyChrome, IL-4-PE, IFNγ-allophycocyanin, B220-allophycocyanin, streptavidin (strep)–allophycocyanin, and OX40-biotin. TCRδ-allophycocyanin, ICOS-PE, and CD40L-allophycocyanin were purchased from eBioscience. PNA-FITC was purchased from Vector Laboratories. Strep-Cascade Yellow was purchased from Invitrogen Molecular Probes. Vγ1.1-bio was a kind gift from Lynn Puddington (University of Connecticut Health Center, Storrs, CT). Cells (500,000–2,000,000 events) were collected on a LSRII (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

RNA and cDNA were prepared from sorted cells as previously described (40). Real-time PCR was also performed as previously described (6) on an i-Cycler (Bio-Rad). A cDNA clone encoding PLZF was a kind gift from Albert Bendelac (University of Chicago, Chicago).

In Vitro Stimulation Assays.

Wild-type and Itk−/− TCRγ+NK1.1+, TCRγ+NK1.1−, TCRγ+CD4+, and TCRγ+CD4− subsets from were activated in vitro with 10 μg/ml of anti-TCRγ biotin (BD Pharmingen) for 72 hours, and supernatants were collected and IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IFNγ were measured by cytometric bead array (CBA) (BD Pharmingen). Cells used for quantitative PCR were stimulated for 10 and 20 hours and examined for IL-4 and IFNγ mRNA. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells from WT and Itk−/− mice were stimulated as previously described (6). Cells were then surface stained for anti-TCRγ and anti-NK1.1, fixed, and permeabilized using a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen) and stained for IL-4 and IFNγ. For ICOS, CD40L and OX40 expression on γδ T cells, cells were stimulated for 24 hours with 10 μg/ml anti-TCRγ. Cells were then surface stained with anti-ICOS, anti-CD40L, and anti-OX40 antibodies.

Serum Analysis.

Blood was collected from WT, Tcrd−/−, Itk−/−, and Itk−/−Tcrd−/− mice. Serum was obtained by spinning the blood at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes and removing the supernatant. Supernatants were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for IgE.

Statistical Analysis.

InStat software (GraphPad) was used to perform two-tailed nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests.

For additional details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Albert Bendelac, Derek Sant'Angelo, Liisa Selin, and Eva Szomolanyi-Tsuda for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI37584 and AI66118 to L.J.B., and CA100382 to J.K.). Core resources supported by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant DK32520 were also used.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0808459106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Berg LJ, Finkelstein LD, Lucas JA, Schwartzberg PL. Tec family kinases in T lymphocyte development and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:549–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosaka Y, Felices M, Berg LJ. Itk and Th2 responses: Action but no reaction. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller C, August A. Attenuation of immunological symptoms of allergic asthma in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase ITK. J Immunol. 2003;170:5056–5063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaeffer EM, et al. Mutation of Tec family kinases alters T helper cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1183–1188. doi: 10.1038/ni734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulsen LK, Hummelshoj L. Triggers of IgE class switching and allergy development. Ann Med. 2007;39:440–456. doi: 10.1080/07853890701449354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felices M, Berg LJ. The tec kinases itk and rlk regulate NKT cell maturation, cytokine production, and survival. J Immunol. 2008;180:3007–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatsumi Y, Pena JC, Matis L, Deluca D, Bluestone JA. Development of T cell receptor-gamma delta cells. Phenotypic and functional correlations of T cell receptor-gamma delta thymocyte maturation. J Immunol. 1993;151:3030–3041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carding SR, Egan PJ. Gammadelta T cells: Functional plasticity and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:336–345. doi: 10.1038/nri797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser B, Eberl M. gammadelta T cells: Novel initiators of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:89–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen L, et al. Immunoglobulin synthesis and generalized autoimmunity in mice congenitally deficient in alpha beta(+) T cells. Nature. 1994;369:654–658. doi: 10.1038/369654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pao W, et al. Gamma delta T cell help of B cells is induced by repeated parasitic infection, in the absence of other T cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1317–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuany-Amorim C, et al. Requirement for gammadelta T cells in allergic airway inflammation. Science. 1998;280:1265–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng B, Marinova E, Han J, Tan TH, Han S. Cutting edge: Gamma delta T cells provide help to B cells with altered clonotypes and are capable of inducing Ig gene hypermutation. J Immunol. 2003;171:4979–4983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizoguchi A, et al. Role of the CD5 molecule on TCR gammadelta T cell-mediated immune functions: Development of germinal centers and chronic intestinal inflammation. Int Immunol. 2003;15:97–108. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandes M, et al. Flexible migration program regulates gamma delta T-cell involvement in humoral immunity. Blood. 2003;102:3693–3701. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermijlen D, et al. Distinct cytokine-driven responses of activated blood gammadelta T cells: Insights into unconventional T cell pleiotropy. J Immunol. 2007;178:4304–4314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lees RK, Ferrero I, MacDonald HR. Tissue-specific segregation of TCRgamma delta+ NKT cells according to phenotype TCR repertoire and activation status: Parallels with TCR alphabeta+NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2901–2909. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2901::aid-immu2901>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovalovsky D, et al. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1055–1064. doi: 10.1038/ni.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage AK, et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity. 2008;29:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itohara S, et al. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: Independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell. 1993;72:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azuara V, Levraud JP, Lembezat MP, Pereira P. A novel subset of adult gamma delta thymocytes that secretes a distinct pattern of cytokines and expresses a very restricted T cell receptor repertoire. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:544–553. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien RL, et al. gammadelta T-cell receptors: Functional correlations. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:77–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen KD, et al. Thymic selection determines gammadelta T cell effector fate: Antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon gamma. Immunity. 2008;29:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vicari AP, Mocci S, Openshaw P, O'Garra A, Zlotnik A. Mouse gamma delta TCR+NK1.1+ thymocytes specifically produce interleukin-4, are major histocompatibility complex class I independent, and are developmentally related to alpha beta TCR+NK1.1+ thymocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1424–1429. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura H, et al. MHC class II-dependent NK1.1+ gammadelta T cells are induced in mice by Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 1999;162:1573–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart CA, et al. Germ-line and rearranged Tcrd transcription distinguish bona fide NK cells and NK-like gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1442–1452. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spits H, Paliard X, Vandekerckhove Y, van Vlasselaer P, de Vries JE. Functional and phenotypic differences between CD4+ and CD4− T cell receptor-gamma delta clones from peripheral blood. J Immunol. 1991;147:1180–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen L, et al. Primary gamma delta cell clones can be defined phenotypically and functionally as Th1/Th2 cells and illustrate the association of CD4 with Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1965–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parravicini V, Field AC, Tomlinson PD, Basson MA, Zamoyska R. Itch−/− alphabeta and gammadelta T cells independently contribute to autoimmunity in Itchy mice. Blood. 2008;111:4273–7282. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svensson L, Lilliehook B, Larsson R, Bucht A. gammadelta T cells contribute to the systemic immunoglobulin E response and local B-cell reactivity in allergic eosinophilic airway inflammation. Immunology. 2003;108:98–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinozzi F, Agea E, Bistoni O, Forenza N, Bertotto A. gamma delta T cells, allergen recognition and airway inflammation. Immunol Today. 1998;19:22–26. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahn M. The role of gammadelta T cells in the airways. J Mol Med. 2000;78:409–425. doi: 10.1007/s001090000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon HU, Seger R. Hyper-IgE syndrome associated with an IL-4-producing gamma/delta(+) T-cell clone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:246–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gascan H, et al. Membranes of activated CD4+ T cells expressing T cell receptor (TcR) alpha beta or TcR gamma delta induce IgE synthesis by human B cells in the presence of interleukin-4. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1133–1141. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunez-Cruz S, et al. LAT regulates gammadelta T cell homeostasis and differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:999–1008. doi: 10.1038/ni977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg LJ. Signalling through TEC kinases regulates conventional versus innate CD8(+) T-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:479–485. doi: 10.1038/nri2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Douhan Iii J, et al. A FLIPR-based assay to assess potency and selectivity of inhibitors of the TEC family kinases Btk and Itk. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2007;5:751–758. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.9982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi M, et al. IgE enhances mouse mast cell Fc(epsilon)RI expression in vitro and in vivo: Evidence for a novel amplification mechanism in IgE-dependent reactions. J Exp Med. 1997;185:663–672. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu KQ, Bunnell SC, Gurniak CB, Berg LJ. T cell receptor-initiated calcium release is uncoupled from capacitative calcium entry in Itk-deficient T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1721–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller AT, Wilcox HM, Lai Z, Berg LJ. Signaling through Itk promotes T helper 2 differentiation via negative regulation of T-bet. Immunity. 2004;21:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.