Abstract

The dietary and movement history of individual animals can be studied using stable isotope records in animal tissues, providing insight into long-term ecological dynamics and a species niche. We provide a 6-year history of elephant diet by examining tail hair collected from 4 elephants in the same social family unit in northern Kenya. Sequential measurements of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen isotope rations in hair provide a weekly record of diet and water resources. Carbon isotope ratios were well correlated with satellite-based measurements of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) of the region occupied by the elephants as recorded by the global positioning system (GPS) movement record; the absolute amount of C4 grass consumption is well correlated with the maximum value of NDVI during individual wet seasons. Changes in hydrogen isotope ratios coincided very closely in time with seasonal fluctuations in rainfall and NDVI whereas diet shifts to relatively high proportions of grass lagged seasonal increases in NDVI by ≈2 weeks. The peak probability of conception in the population occurred ≈3 weeks after peak grazing. Spatial and temporal patterns of resource use show that the only period of pure browsing by the focal elephants was located in an over-grazed, communally managed region outside the protected area. The ability to extract time-specific longitudinal records on animal diets, and therefore the ecological history of an organism and its environment, provides an avenue for understanding the impact of climate dynamics and land-use change on animal foraging behavior and habitat relations.

Keywords: C4 photosynthesis, carbon-13, stable isotopes, wildlife conservation

Variation in temporal and spatial resource quality and abundance can have strong affects on animal ecology and community resource partitioning (1). In particular, changes in species composition and abundance at seasonal and longer time scales strongly influences diet and, as a result, community dynamics and the life history of animals (2, 3). Quantifying and dating fine scale foraging behaviors is difficult, typically causing foraging studies to focus on averages compiled from observations and measurements collected from multiple, and often unknown, individuals (e.g., refs. 4–6); such dietary data are difficult to relate to spatially or temporally explicit resource changes. Quantifying the long-term diets of a single individual requires continuous observation, often in the face of cryptic life stages or range shifts and seasonal migration. As such, detailed dietary monitoring through observations is intractable for many species, although the importance of quantifying climate or human mediated diet changes that many species are experiencing is more critical than ever (7). Recent developments in stable isotope ecology enable the derivation of temporally explicit diet records, offering a means by which foraging decisions and the effect of ecological shifts on species can be recorded and compared over time.

Stable isotopes in animal tissues record dietary preferences and ecological conditions experienced by an individual, with substrates such as hair containing longitudinal records of isotope ratios. 13C/12C, 15N/14N, and 34S/32S ratios record dietary input and habitat characteristics (e.g., refs. 8–11), and D/H and 18O/16O ratios record information abouit water sources (12). One of the most strongly delineated isotopic signals occurs in the δ13C ratios of plants, using the C3 and C4 photosynthetic pathways: Most C4 plants have δ 13C values between −11 and −14‰, whereas most C3 plants have δ13C values between −25 and −29‰. Tropical grasses almost exclusively use the C4 pathway; most trees, shrubs, and forbs use the C3 pathway. Therefore, isotope ratios in animal tissues such as hair, which record dietary input, provide a clear indicator of these dietary preferences. Studies of African savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) show that they prefer grass during the wet season but rely on browse during the dry season (6, 13–16). It is anticipated that significant changes in vegetation will take place in sub-Saharan Africa in the next few decades because of resource competition between animals and humans and because of global climate change. Therefore, it is of interest to trace the relationship between elephant diet and vegetation change over a long time interval, particularly in respect to the keystone role elephants play in savanna ecosystems (17, 18).

Here, we present a 6-year chronology of temporally fine-scale data on diet changes of a single elephant family in Samburu-Buffalo Springs National Reserves in northern Kenya. This study builds on our long-term observations of elephants in northern Kenya (19–24), on our interests in understanding isotope incorporation into animal tissues (12, 25–30), and on our interests in applying those principles to wildlife ecology (14, 15, 16). Diet records are interpreted from multiple hair samples collected annually or subannually over the study interval. We compare this diet record to rainfall and remotely sensed records of net primary productivity (NPP) in the form of normalized differential vegetation index (NDVI) data from the same region. Diet shifts are also related to reproductive activity and spatial behavior. With ecological and environmental changes occurring from regional to global scales (including land use change and global climate change) as the result of human activities, shifts in ecological communities are likely to occur. Monitoring diet changes as food resource availability shifts via continuous, long-term isotope records provides an important means to identify and study the effect of environmental change on an animal's ecological interactions.

Results

Background Isotope Values of the Environment: Plants and Water.

Over 250 individual plant samples were collected from October 2004 to July 2005, and in May 2006; this former interval corresponded to a drier than normal period whereas the latter was at the end of a near-normal “long rains” season. The average δ13C of C3 plants was −27.4 ± 1.0‰ and that for C4 plants was −13.4 ± 1.0‰ (Table S1). Ranges in δ13C of individual plants and plant species varied by >3‰, generally having more negative values during the wet season and more positive values during the dry season for C3 plants. No significant correlations between NDVI and δ13C, δ15N, or %N were found for the 10-month collection period.

Nitrogen isotopes showed that only Indogofera could be considered to be N-fixing during this period. Indogofera schimperi had δ15N values near 0‰; most of these samples were from the more-xeric upland localities; I. schimperi from riparian zones had higher %N and higher δ15N values (+3 to + 9‰). All I. spinosa samples had high δ15N values (+4 to + 11‰) regardless of %N. δ15N values of all Acacia (Acacia eliator, Acacia reficiens, Acacia tortilis) had elevated δ15N values, ranging between + 3.5 and + 15.9‰ and cannot be considered to be exclusively N-fixing plants in this environment. Grasses and sedges generally had high δ15N values with average values as high as + 12‰ (Table S1).

An 18-month survey of δ18O and δD in river water from the Ewaso N′giro showed seasonal fluctuations; δD and δ18O values were more negative in the wet season and more positive in the dry season. Deuterium excess [Dxs = δD − 8 δ18O (31)] is used to evaluate meteoric waters with respect to the global meteoric water line [GMWL: δDGMWL = 8 δ18O + 10; (32)]. Two waters with high Dxs values (>35‰) were not included in the trends discussed below. Stable isotope ratios of the Ewaso N′giro during the wet season (NDVI monthly average >0.25) are well correlated (r2 = 0.94) with a trend of δD = 6.8 δ18O + 7.1, a similar slope and intercept as the GMWL and to other unevaporated meteoric waters in Kenya (33, 34). Waters from the river in the dry seasons (monthly average NDVI < 0.25) show evaporative enrichment of D and 18O: δD = 4.1 δ18O + 3.3 (r2 = 0.81).

Growth Rates and Correlations Between Members of the Same Family.

Hair was collected and analyzed from 4 different members of the same family unit; Royals: mother Queen Elizabeth (M1) and siblings Victoria (M2), Cleopatra (M4), Anastasia (M5), and growth rates were calculated using the method of Wittemyer (16). Growth rates of the tail hairs were between 0.73 and 1.04 mm/day. We found little evidence for variable growth rates within a single hair even during periods of high metabolic stress related to reproduction (16). Individual hair samples were up to 580 mm long (median: 460 mm) and had individual chronologies covering up to 20 months (median: 18 months). The correlation between isotope chronologies between different familial members was very high (r2 = 0.79), slightly lower than correlations between hairs collected from a single individual (r2 = 0.89 to 0.93) but higher than two individuals from different family units (r2 = 0.44; ref. 16). Fig. S1 shows the δ13C and δ15N records for hair samples collected from M4 and M5 in July 2004.

Isotope ratios from dung samples collected on the same days from M4 and M5 were also highly correlated [reduced major axis (RMA): δ13C(M5) = 1.133 δ13C(M4) − 4.79; r2 = 0.68; n = 13]. Unfortunately, few samples were collected during the wet season, when the greatest variance in isotope values occurred, because the focal elephants dispersed to regions inaccessible to our field team during these periods.

Diet History of Royals Family Unit Based on Carbon Isotopes.

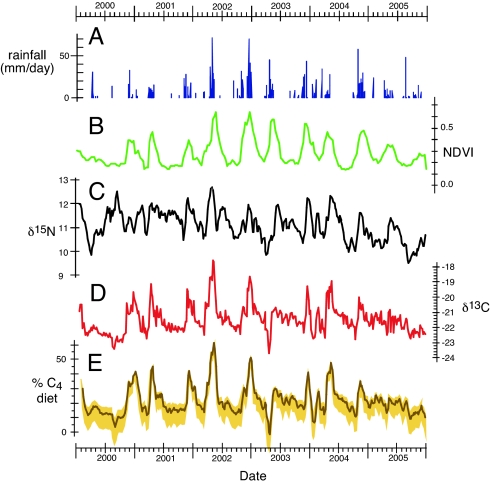

Because of the high correlation and overlap between different hairs collected from different individuals within the same family unit, a long-term composite diet history of the “Royals” family unit was compiled using the isotope profiles from hairs of different individuals. Fig. 1 shows rainfall, NDVI, δ15N, δ13C, and estimated C4 biomass in diet for the 6-year period from 2000 through the beginning of 2006. Biomass estimates were calculated using 3 different C3 and C4 mixing model end-members. The nominal case, shown as a solid line in Fig. 1E, uses the average δ13C values for the >250 plant samples from the Samburu. C3 plants tend to become more positive and C4 plants tend to be slightly more negative in xeric environments (35, 36); thus the mixing lines are likely to be slightly compressed during the dry season and slightly expanded in the wet season compared with the nominal case. To better assess the possible variability in actual C4 biomass contributions, we used C3 and C4 end-member values based on samples collected during the wet and dry seasons of −28.5‰ and −12‰ (“wet-season” mixing line) and −26 and −14‰ (“dry-season” mixing line). This analysis has an important consequence: baseline (i.e., the lower “floor” of C4 biomass intake) values of C4 biomass for the nominal and “wet-season” cases are ≈15–20% C4 biomass, whereas for the “dry-season” case the baseline is ≈5% C4 biomass (Fig. 1E). However, the maximum C4 intake during the wet season is little affected by these different mixing line values because of the “cross-over” of the mixing lines occurs at ≈50% C4 biomass (i.e., the 50% C4 values for the wet season case, nominal case, and dry season case are −20.5‰, −20.4‰, and −20‰, respectively). Average percentage of C4 biomass intake over the entire 6-year period is estimated to be 24%, 21%, and 12% for the “wet season,” “nominal,” and “dry season” cases, respectively, with maximum intake values between 58% and 60% for all 3 cases occurring in May 2002.

Fig. 1.

Nitrogen and carbon isotope data and the estimated percentage of C4 biomass in diet derived from the composite hair profile demonstrate seasonal oscillations matching fluctuations in rainfall and NDVI from the Samburu region. (A) Rainfall from Archer's Post. (B) NDVI of Samburu region. (C) δ15N of composite hair profile. (D) δ13C of composite hair profile. (E) Estimated percentage of C4 biomass in the diet (3-point running average). The solid line is using the model as described in Methods, and the C3 and C4 end-member values of −27.4 and −13.4‰, respectively. Shaded envelope gives ranges encompassed by seasonal end-member C3 and C4 values of −28.5‰ and −12‰ (wet season top of envelope), respectively, and −26‰ and −14‰ (dry season bottom of envelope), respectively.

Results of Nitrogen Isotope Analyses.

δ15N values for hair from the Royals family unit are shown in Fig. 1C. δ15N tends to have high values when δ13C values are also high (with correlation coefficients of r2 > 0.7 for periods of 3 months or longer), demonstrating that C4 plants tend to have a higher δ15N value in the ecosystem as corroborated from vegetation samples presented previously. This is true for the single-day survey of plants and for dung samples: δ13N in dung is positively correlated with δ13C [RMA: δ15Ndung = 0.39 δ13Cdung + 16.2 (r2 = 0.63; n = 26)]. Sponheimer (25) observed 0.8‰ depletion in δ13C in dung compared with diet for several different domestic species (cattle (Bos taurus), goat (Capra hircus), alpaca (Lama pacos), llama (Lama glama), rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)). δ15N, however, is enriched in 15N compared with the diet by 0.5 to 3‰ (26, 37, 38). Elephant dung consist of poorly digested material so that the isotope fractionation during digestion is likely to be less than in animals with a more efficient digestive physiology.

Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotope Results from Hair.

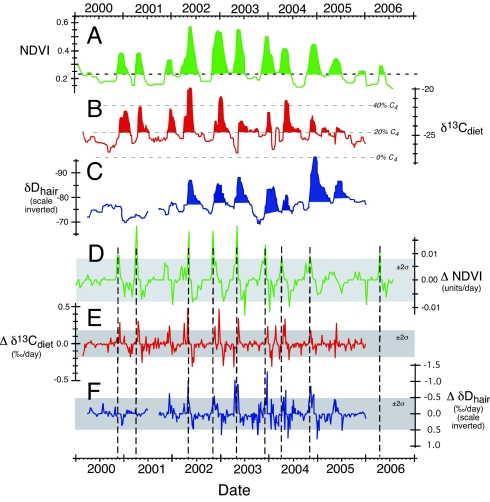

Fig. 2 shows the record of NDVI, δ13Cdiet and δDhair for the ≈6-year period presented as the median value over 1-month periods; here we also provide the first derivatives of each of these records (ΔNDVI, Δδ13Cdiet, ΔδDhair, respectively). There are 9 periods where the ΔNDVI exceeds the 2σ (standard deviation) value, and 1 where it approaches the 2σ value (Fig. 2D). These are the periods of most rapid change in the vegetation index and serve as a reference for changes in carbon and hydrogen isotope changes in hair.

Fig. 2.

Median values for NDVI, δ13Cdiet, and δDhair. All values are ≈1 month medians. (A) Median values of NDVI. (B) Median values of δ13C in diet. (C) median values of δD in hair (scale inverted). (D) First derivative of NDVI record: ΔNDVI (units are NDVI/day). (E) First derivative of δ13C record: Δδ13C (units are ‰/day). (F) First derivative of δD of hair: ΔδD (units are ‰/day). (D–F) Shaded horizontal boxes show ± 2σ for ΔNDVI, Δδ13C, and ΔδD; dashed vertical lines show the maximum values (> 2σ) for ΔNDVI.

Discussion

Long-Term Diet, NDVI, and Rainfall.

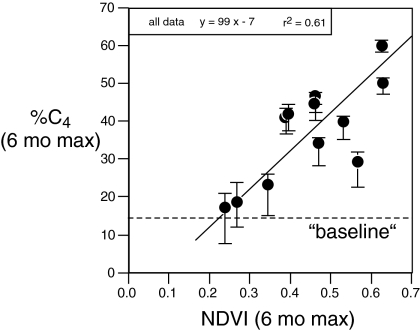

The fraction of dietary C4 biomass in the Royals family unit was strongly seasonal, with rainy season δ13Cdiet values generally 3‰ to 6‰ higher than in the dry season. This corresponds to a baseline diet between 5% and 20% C4 biomass (Fig. 1E) in the dry season to peaks between 40% and 60% C4 biomass in the wet season for this family unit. To compare maximum NDVI and maximum percentage C4 contribution to the elephant diets over the 6-year interval we considered the periods from 1 March to 1 September and 1 September to 1 March to capture the 2 rainy seasons in this environment. The fraction of C4 biomass in the diet (i.e., C4-grasses) is highly correlated with NDVI (Fig. 3; RMA: %C4 = 99 * NDVI - 7; r2 = 0.61). Therefore, the fraction of C4 biomass in the diets of savanna elephants is highly dependent on seasonal rain and net primary productivity (NPP). During periods of low NPP, the maximum percentage of C4 biomass was <30%, whereas during favorable periods it exceeded 40% for this family unit. The minimal increase in dietary grass during the droughts of 2000 and in late 2005, as exhibited by the NDVI and the stable isotope records, provides further evidence of the strong relationship between NPP/rainfall and diet among elephants.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between maximum NDVI and maximum percentage of C4 biomass calculated in diet for 6-month time intervals from 2001 to 2006; reduced major axis (RMA) used to calculate regression. Time intervals were from 1 March to 1 September and from 1 September to 1 March, so as to differentiate the “long” and “short” rains, respectively (usually April–May and November–December). The solid line is for all data and vertical bars show the total range of calculated diets, using the 3 end-member mixing values discussed in Diet history of Royals Family.

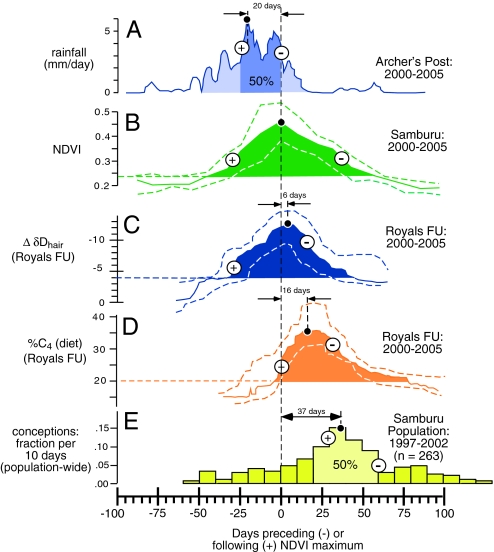

The timing of diet in forage and water isotopic shifts are strongly related to changing ecological conditions, as exemplified by the synchronicity of the maximum rates of increase, peaks, and maximum rates of decrease among rainfall, NDVI, δDhair, and δ13Cdiet during the 6-year study (Fig. 4). These temporal relationships are compared with the timing of reproduction in the greater Samburu population (22, 29). Seasonal diet changes were abrupt at the beginning of the wet season but tapered off gradually at the end of the wet season (Fig. 4D). Changes in δ13Cdiet track the chronology of NDVI values but lags changes in NDVI by several weeks. The temporal lag between δ13Cdiet and NDVI was the same when comparing either NDVImax with δ13Cmax or ΔNDVImax with Δδ13Cmax (Figs. 2 and 4). Changes in δD are more closely synchronized with NDVI, where the maximum rate of increase and peak occur simultaneously (Fig. 4). The strong synchronicity between NDVI and δDhair, which lags the onset of seasonal rains, demonstrates the importance of changing water sources associated with the seasonal rains; this could be in the form of new or replenished drinking water supplies and forage-derived water. The delay between changes in NDVI and diet switching appears in part to relate to the handling time associated with short, early season grasses; the new-growth grass must grow to a certain height before it can readily be grasped by the trunk (G.W., personal observation). In addition, protein quantity in savanna grasses varies over the wet season (40) such that grass quality peaks toward the latter part of the growing phase as grass species seed. This peak in protein content is probably influential to the timing of dietary switching and corresponding peak in reproductive activity. Previous endocrine work demonstrated that the elevation of pregnanolone levels (a hormone controlling ovulation) is strongly correlated with seasonal productivity (23). The peak in conceptions occurs ≈5 weeks after the peak in NDVI, and ≈3 weeks after the peak in C4 grass consumption (Fig. 4E). The gestation period for elephants is 22 months; thus the peak in births occurs at the beginning of the rainy season when water is readily available and grass productivity is about to increase (22). The timing of dietary protein pulses related to peak grass consumption is the likely driver of this ecological and physiological relationship.

Fig. 4.

Isotopic chronologies derived from elephant tail hairs demonstrate that isotopic shifts related to water resources and diet (C3 browse versus C4 grass) were synchronized with seasonal rainfall pulses and their impact on vegetation (here measured as NDVI). The average timing of the initiation (begin shaded area), maximum increase (+), peak values (black circle), maximum decrease (−), and end of each peak (end of shaded area) for: mean (5-day average) daily rainfall (A); median NDVI (B); median ΔδD (C); median δ13C (D); and conceptions (E). All are referenced to the maximum NDVI value, and dashed lines show the 25th and 75th percentiles.

Thus, the isotope and precipitation archives, satellite-based measurements of productivity, and ground observations record the sequence of rains, changes in NPP, changes in diet, and periods of highest fertility of elephant females. Approximately 80% of the seasonal rainfall occurs before peak NDVI (Fig. 4A), and NDVI peaks a few weeks after peak rainfall (Fig. 4B). The change in the isotopic composition of body water, as recorded by δD in hair, closely echoes NDVI measurements (Fig. 4C), with the most negative δD values occurring within a few days of peak NDVI. A major increase in C4 grass consumption occurs near the period of peak NDVI, with the maximum consumption of grass being reached ≈2 weeks after peak NDVI (Fig. 4D). Grass consumption reaches baseline values ≈75 days after peak NDVI. The peak in conceptions occurs ≈5 weeks after peak NDVI, and well after the peak in C4 grass consumption (Fig. 4E).

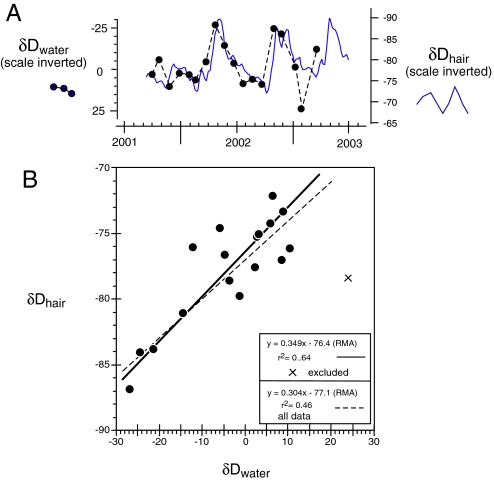

Changes in δD in Hair and Water.

Fig. 5 shows that the δD of local river water and the δD of elephant hair are well correlated. For this study, we also observed a strong relationship among these parameters (δDhair = 0.30 δDwater − 77‰; r2 = 0.46; n = 18); the slope of the relationship is similar to that of humans (12). Thus, the δD of elephant tail hair recorded local changes in δD of local waters. However, the δD response in times when the rains were absent, as indicated by low NDVI values, was muted (Fig. 2). In contrast, δ18O of hair and 18O of river water were not significantly correlated (δ18Ohair = 0.0623 δ18Owater + 21.037; r2 = 0.016; n = 18), which was surprising given other studies that have demonstrated a significant relationship between hair and water oxygen isotope values (12, 30, 41).

Fig. 5.

Relationships between the isotope composition of local water and hair. (A) δD values for elephant hair and for water collected from the Ewaso N′giro at Samburu Reserve for 18 months from October 2001 through March 2003. The value for the elephant hair is a ≈15-day average (3-point mean) centered on the day of the water collection (± 3 days). (B) Correlation between δD values of elephant hair and water from the Ewaso N′giro River (as in 6A). Lines are for Reduced Major Axis regression (52, 53).

Over the last decade, the primary water source in the study system, the Ewaso N′giro river, has maintained only subterranean flow during droughts and extended dry seasons. During these times, surface water is only available from isolated springs, although elephants often dig for water in the dry river bed.

Comparison of δ13Cdiet and δ15N.

δ13C and δ15N were compared in both dung samples and in the hair-derived diet-estimate (see Methods). Dung samples from the Royals family unit were collected primarily in the dry seasons when the family unit was more easily seen. Many periods of high correlation between δ15N and δ13C in hair occurred (Fig. 1). Both the dung and estimated diet correlations give δ15N values between 5 and 7‰ for the C3 end-member plants, and between 11 and 16‰ for the C4 end-member plants. This is in agreement with observations showing that plant δ15N values for plants using different photosynthetic pathways are generally higher in C4 plants than in C3 plants in these regions (Table S1). The only N-fixing plant observed in the vegetation survey was I. schimperi, a favorite C3 food item of elephants in every season.

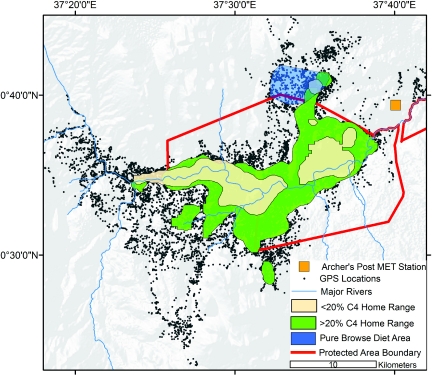

Spatial Distribution, NDVI, and Diet Change.

The movements of at least 1 member of the Royals family unit were recorded by a global positioning system (GPS) collar the entire length of this study. Fig. 6 shows the 95% kernel (42) incorporating the location of the Royals family unit. During periods of low (<20%) C4 intake the family unit was usually within ≈2 km of the riparian corridor of the Ewaso N′giro (Fig. 6). During periods when C4 biomass was a high portion of the diet (>20% C4), the family unit was found much further from the riparian corridor, and was more commonly found outside the Samburu and Buffalo Springs National Reserve boundaries (Fig. 6). These linkages and covariances between water and food distributions have significant management implications, particularly when interannual shifts in seasonal precipitation alter availability of C4 food resources.

Fig. 6.

Regional map displaying GPS positions (black dots) collected from M4 and M5 in and around the national reserves (red polygon overlayed on a digital elevation map) during the 6-year study. The 95% kernel home range (42) retracted to areas in close proximity of the permanent Ewaso N′giro river (blue line) during dry season periods when diets were <20% grass (beige polygon), whereas ranges expanded to regions further from the river as the proportion of grass increased (green polygon). The only period when diets were 100% browse (blue polygon) occurred north of the protected area boundary in a heavily grazed community conservation region.

Cattle are generally excluded from the Samburu and Buffalo Springs Reserves, resulting in little competition between elephants and livestock for resources within these protected areas. Yet the stable isotope data suggest periods when these animals may compete for resources. Late April to early May 2003 was a time of anomalous diet for the Royals family unit (Figs. 1 and 2, and Fig. S1). During this apparently normal rainy season, the Royals family unit did not switch to grazing as was normal, but had a diet that was virtually 100% C3; in fact, it was the most negative δ13C value for the entire 6-year observation period (Figs. 1 and 2). During this period GPS data showed that the elephants were mostly beyond the northern edge of Samburu Reserve, in an area heavily used by the local pastoralists (Fig. 6). The region is an Acacia mellifera and A. reficiens woodland subject to heavy overgrazing by livestock. Although the reasons for use of this area by the Royals family unit are not known, the impact of overgrazing by cattle on the typical wet season diet of elephants is clear; competition with cattle results in poor access to high quality grass forage because cattle keep the grass very short and out-compete elephants for this resource. This example shows that human activities have a large impact on elephant diets and ecological function.

Conservation Implications.

The findings presented here have important implications for management of elephant populations in relation to global climate change on one scale, and local land use change at another scale. NDVI can change over the long term for many reasons, but increasing temperature in regions with minimal rainfall is likely to decrease NPP and NDVI. Similarly, changes in land use due to increased stocking rates as human population increases can result in changes in NDVI.

Elephants are a keystone species in savanna ecosystems, shaping the relative densities of grass and woody vegetation (17, 40). In many ecosystems, elephant range restriction concentrates and amplifies impacts of elephants on vegetative communities, leading to effects on species composition across trophic levels (43, 44). With climate models predicting greater variation in annual rainfall in Eastern Africa (45), the dynamics between elephant populations and their environments are likely to be strongly regulated by the relationship between climatic fluctuation and diet. During droughts, the combination of constrictions of feeding ranges to areas with permanent water (Fig. 6) and increased reliance on woody vegetation by elephants is likely to extenuate the impacts on vegetative species age distributions and composition (46). In addition, elephant ranging behavior, sociality and reproduction are strongly mediated by climate variation (22–24). Climatic-induced diet changes may alter recruitment regimes—driving more pronounced seasonality in conceptions related to the proportion of C4 vegetation in female diets.

Conclusions

Long-term diet histories of mammals are recorded in animal tissues such as hair, and these histories can be interpreted in the context of stable isotope ecology. A 6-year history of a single elephant family unit in northern Kenya shows that seasonal diet changes are well correlated with changes in NDVI. During the dry season, δ13C values have a baseline value that indicates a diet composed of 5% to 20% C4 biomass depending on the values used for end-member C3 and C4 vegetation. The absolute amount of grass consumption in any wet season is well correlated with the maximum value of NDVI associated with that wet season, and the peak in grass consumption occurs ≈2 weeks after the peak in NDVI. These results show the adaptability of elephants in the face of climate change. However, long-term changes in NDVI, whether due to land use change, competition with livestock, or to long-term climate trends, are likely to be accompanied by changes in the amount of grass available to be consumed by elephants during the wet season—shaping the ecological role played by elephants across their range.

Changes in the δD of hair are well correlated with the isotope composition of local drinking water, and the minimum value for δD occurs at essentially the same time as the peak NDVI. The high temporal resolution of hair δD can be used as a unique ecological tracer in future research. Not only can δD accurately identify the timing of seasonal resource changes, but coupling this data with fine-scaled spatial information on water sources can offer new directions of research regarding animal behavior.

Tail hair of wild animals represents an archive of dietrary behavior that provides an opportunity to quantify diet and the environmental conditions experienced by those animals. This archive can be accurately dated and is closely linked to local climate parameters. Such information can be used to reconstruct historic climatic events at fine temporal scales and spatial scales if coupled with GPS observations. It also provides insights to resource use and environmental interaction not previously accessible for animal ecological and evolutionary studies.

Methods

Study Area and Population.

The elephants (L. africana) sampled in this study inhabit the region in and around the 220 km2 Samburu and Buffalo Springs National Reserve in northern Kenya (37.5° E 0.5° N). These semiarid parks are dominated by Acacia-Commiphora savanna and scrub bush and located along the Ewaso N′giro River (Fig. 7), the major permanent water source in the region (47). Rainfall averages ≈350 mm per year and occurs during biannual wet seasons that generally take place in April/May and November/December; Archer's Post (Fig. 6) is the nearest meteorological station. The elephants using these reserves (Fig. 7) are individually identified, following well-established methods (19), allowing hair sampling from the same individual across time. For a more detailed description of the study population and ecology of the study area, see ref. 16.

Fig. 7.

(A) Elephant family crossing the Ewaso N′giro in Samburu and Buffalo Springs Reserve (photo by M. Kephart). (B) Elephant with tail hair typical of that used in this study.

GPS radio collars were fitted to elephants in the Samburu National Reserve, northern Kenya, between 2001 and 2006 (20). Collars were programmed to record positions at hourly intervals, offering detailed records of movement. Tail hairs (Fig. 7) from each elephant were collected during immobilization operations while the collars were being fitted, and later when batteries were being changed or when the collars were being removed. We sampled 4 different breeding females from the same family unit (Royals), known to maintain direct proximity with each other >80% of the time (21). Two of the sampled females, M4 (Anastasia) and M5 (Cleopatra), were fitted simultaneously with GPS radio collars for a 6 month period, during which they spent >95% of the time within 1 km of each other (80% within 250 m), used identical ranges, and moved similar daily distances. Three of the family unit members, including the 2 radio-tracked females, were siblings, daughters of the 4th (M1: Queen Elizabeth), who died in 2000.

Dung samples were collected during observational transects during the years 2004–2005. Plant samples were collected from 1 riparian zone 3 times per month, for 10 months from October 2004 through July 2005. A single collection of plants was made on a single day during the wet season (21 May 2006); we visited 14 sites ranging from riparian zones to upland bush zones. Water samples were collected for 18 months, 1 sample monthly, from the Ewaso N′giro River from October 2001 to March 2003.

Laboratory Methods.

Hair samples were wiped with acetone to remove dirt, grit, and oils. Hair samples were serially sampled, with 1 sample collected from each 5-mm interval for δ13C and δ15N analysis (≈500 μgr); the same segments were used for δD and δ18O organic analysis (≈150 μgr). Five mm corresponds to ≈6 days for these samples. Dung and plant samples were oven-dried at 80 °C for 24 h, homogenized, and ground before analysis.

13C/12C and 15N/14N ratios of elephant hair, dung, and plant material were measured on an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS: Finnegan 252) after combustion in a flow-through modified Carlo–Erba system. Values are reported using the conventional permil (‰) notation where:

an analogous terminology describes D/H, 15N/14N, and 18O/16O ratios. Standards are V-PDB and AIR for δ13C and δ15N, respectively, and V-SMOW for δD and δ18O. Isotope enrichment between hair and diet is ≈3‰ for both δ13C and δ15N. For δD and δ18O analysis of hair, ≈150 μg of hair from samples or internal standards were equilibrated with water vapor in the laboratory atmosphere, desiccated under vacuum for 7 days, and analyzed. Internal standards were used to correct for exchangeable H (48). δD and δ18O were analyzed by pyrolization of the hair to H2 and CO in an elemental analyzer furnace (TC-EA) and analyzed for 2H and 18O content, using an IRMS operating in continuous mode (49). Hair samples were analyzed using a zero-blank carousel to prevent isotope exchange during the analysis period. Results are presented in the ‰ notation, using V-SMOW as the standard. Water analyses were analyzed using Zn-reduction to produce H2 gas and by CO2 equilibration for δ18O before analysis using IRMS.

Data Analysis.

We used 10-day composite NDVI data available through Satellite Probatoire d'Observation de la Terre (SPOT) to determine NPP changes in season across the study area. NDVI is a remote sensing index value calculated as the ratio between red and near infrared reflection that is highly correlated with green (photosynthetically active) biomass (50, 51). Remotely sensed data provides a direct measure of photosynthetic activity over large spatial regions, offering advantages over the classically-used point sampled rainfall data in areas, like the study region, where weather stations are sparse (39). Isotope profiles for each elephant were compared with longitudinal 10-day NDVI records to determine the impact of seasonality on diet.

Growth rates of hairs were determined by comparing overlapping stable isotope patterns of δ13C and δ15N (14, 16) and are independent of NDVI measurements, rainfall, and observational data (e.g., births, pregnancies). We estimated the dietary components of C3 and C4 biomass, using the model of Cerling et al. (29); we assume the same parameters for isotope turnover pools as determined by Ayliffe et al. (28) because these parameters are not yet known for elephants and previous analysis demonstrated only minor variation in model parameters provided plausible diet estimates (16). In the dietary analysis, we used portions from 8 different hairs to make a single composite reference for the Royals family unit. For C3 and C4 end-member δ13C values, we use the values of −27.4 and −13.4‰, respectively (unless otherwise specified), as determined from average δ13C values of >250 plants sampled in the local ecosystem during the course of this study.

We estimated the δ15N diet using the isotope turnover model of Ayliffe et al. (28), using the same turnover parameters for N as for C; we use a 3‰ enrichment for diet-hair (27). The parameters are not known but we assume that similar skeletal elements of amino acids are correlated for amino acids involved in hair growth.

Seasonal peaks in NDVI, δD, and δ13C of diet (related to C4 biomass) were compared across seasons by estimating the major elements of the shape of their respective seasonal cycles: distinguishing initiation (or wet season onset), maximum increase, peak value, maximum decrease, and end point (or dry season onset), using a 5-point median plot (median value, ≈1 month), which preserves peaks in rates of change. NDVI and δ13C increase during the wet season, whereas δD of drinking water decreases during these intervals and is therefore plotted using an inverted scale. The peak values for NDVI, δD, and δ13C diet were tabulated; the periods of maximum change was determined from the first derivative of the peak curve. For peak initiation we used a threshold value of 0.23 for NDVI, 20% C4 diet component for δ13Cdiet, and <4‰ below the previous peak value for δD. Peak ends were considered to be the threshold value of 0.23 for NDVI, 20% C4 diet component for δ13Cdiet, and a return to the peak initiation value for δD. Regressions between stable isotopes are calculated using the reduced major axis (RMA) because relative errors in the dependent and independent variables are of similar magnitude (52, 53). No distinction was made between peaks associated with the “long” versus “short” rains [during the period 2000–2005 the “long rains” and “short rains” had average rainfall values of 143 mm (n = 6; max: 259 mm; min: 63 mm) and 193 (n = 6; maximum 356 mm; minimum: 55 mm), respectively].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank David Daballen, Daniel Lentipo, and Chris Leadismo for assisting in the collection of samples and in observations in the field; Leslie Chesson, Brad Erkkila, Scott Hynek, Todd Robinson, and Jared Singer for assistance in laboratory; Mahala Kephart for photography; the Government of Kenya for permission to carry out this research; and Daryl Codron and Antoine Zazzo for their critical reading of the manuscript. Field work was supported by the Save-The-Elephants and the Packard Foundation. Isotope measurements were done in the Stable Isotope Ratio Facility for Environmental Research laboratory at the University of Utah. This work was carried out under Convention on International Trade In Endangered Species permits US831854, 02US053837/9, and 08US159997/9.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902192106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Stearns SC. The Evolution of Life Histories. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostfeld RS, Keesing F. Pulsed resources and community dynamics of consumers in terrestrial ecosystems. Trends Ecol Evol. 2000;15:232–237. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)01862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang LH, Bastow JL, Spence KO, Wright AN. What can we learn from resource pulses? Ecology. 2008;86:621–634. doi: 10.1890/07-0175.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talbot LM. Food preferences of some East African wild ungulates. East African Agri Forest J. 1962;27:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field CR. The food habits of wild ungulates in Uganada by analysis of stomach contents. East African Wildlife J. 1972;10:17–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Codron J, et al. Elephant (Loxodonta africana) diets in Kruger National Park, South Africa: Spatial and landscape differences. J Mammal. 2006;87:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicole S, Worby A, Leaper R. Changes in the Artic sea ice ecosystem: Potential impacts on krill and baleen whales. Marine Freshw Res. 2008;59:361–382. [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1978;42:495–506. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1981;45:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connell TC, Hedges REM. Investigations into the effect of diet on modern human hair isotopic values. Amer J Phys Anthro. 1999;108:409–425. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199904)108:4<409::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macko SA, et al. Documenting the diet in ancient human populations through stable isotope analysis of hair. Phil Trans R Soc Ser B. 1999;354:65–76. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehleringer JR, et al. Hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios in human hair are related to geography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2788–2793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712228105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kingdon J. An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. Vol IIIB Large Mammals. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cerling TE, et al. Orphans' tales: Seasonally dietary changes in elephants from Tsavo National Park, Kenya. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclim Palaeoecol. 2004;206:367–376. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerling TE, et al. Stable isotopes in elephant hair documents migration patterns and diet changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:371–373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509606102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittemyer G, Cerling TE, Douglas-Hamilton I. Establishing chronologies from isotopic profiles in serially collected animal tissues: An example using tail hairs from African elephants. Chem Geol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laws RM. Elephants as agents of habitat and landscape change in East Africa. Oikos. 1970;21:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen-Smith N. Megaherbivores: The influence of very large body size on ecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittemyer G. The elephant population of Samburu and Buffalo Springs National Reserves, Kenya. African J Ecol. 2001;39:357–365. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douglas-Hamilton I, Krink T, Vollrath F. Movements and corridors of African elephants in relation to protected areas. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92:163–168. doi: 10.1007/s00114-004-0606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittemyer G, Douglas-Hamilton I, Getz WM. The socio-ecology of elephants: Analysis of the processes creating multi-tiered social structures. Anim Behav. 2005;69:1357–1371. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittemyer G, Rasmussen HB, Douglas-Hamilton I. Timing of conceptions and parturitions in relation to NDVI variability in free-ranging African elephant. Ecography. 2007a;30:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wittemyer G, Ganswindt A, Hodges K. The impact of ecological variability on the reproductive endocrinology of wild female African elephants. Horm Behav. 2007b;51:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittemyer G, Getz WM, Vollrath F, Douglas-Hamilton I. Social dominance, seasonal movements, and spatial segregation in African elephants: A contribution to conservation behavior. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2007c;61:1919–1931. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sponheimer M, et al. An experimental study of carbon isotopes in the diets, feces and hair of mammalian herbivores. Can J Zool. 2003a;81:871–876. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sponheimer M, et al. An experimental study of nitrogen flux in llamas: Is 14N preferentially excreted? J Archaeol Sci. 2003b;30:1649–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sponheimer M, et al. Nitrogen isotopes in mammalian herbivores: Hair δ15N values from a controlled-feeding study. Intern J Osteol. 2003c;13:80–87. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayliffe LK, et al. Turnover of carbon isotopes in tail hair and breath CO2 of horses fed an isotopically varied diet. Oecologia. 2004;139:11–22. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerling TE, et al. Determining biological tissue turnover using stable isotopes: The reaction progress variable. Oecologia. 2007;151:175–189. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podlesak DW, et al. Turnover of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in the body water, CO2, hair and enamel of a small mammal after a change in drinking water. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2008;72:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gat JR. Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in the hydrologic cycle. Ann Rev Earth Planet Sci. 1996;24:225–262. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craig H. Isotopic varations in meteoric waters. Science. 1961;133:1702–1703. doi: 10.1126/science.133.3465.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barton CE, Solomon DK, Bowman JR, Cerling TE, Sayer MD. Chloride budgets in transient lakes: Lakes Baringo, Naivasha, and Turkana, Kenya. Limnol Oceanogr. 1987;32:745–751. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonfiantini R, Roche M-A, Olivry J-C, Fontes J-C, Zuppi GM. The altitude effect on the isotopic composition of tropical rains. Chem Geol. 2001;181:147–167. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehleringer JR, Cooper TA. Correlations between carbon isotope ratio and microhabitat in desert plants. Oecologia. 1988;76:562–566. doi: 10.1007/BF00397870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buchmann N, Brooks JR, Rapp KD, Ehleringer JR. Carbon isotope composition of C4 grasses is influenced by light and water supply. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;9:392–402. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steele KW, Daniel RMJ. Fractionation of nitrogen isotopes by animals: A further complication to the use of variations in the natural abundance of 15N for tracer studies. J Agri Sci. 1978;90:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutoh M, Koyama T, Yoneyama T. Variations in natural 15N abundances in the tissues and digesta of domestic animals. Radioisotopes. 1987;36:74–77. doi: 10.3769/radioisotopes.36.2_74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen HB, Wittemyer G, Douglas-Hamilton I. Predicting time-specific changes in demographic processes using remote-sensing data. J Appl Ecol. 2006;43:366–376. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dublin HT, Sinclair ARE, McGlade J. Elephants and fire as causes of multiple stable states in the Serengeti Mara Woodlands. J Animal Ecol. 1990;59:1147–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowen GJ, et al. Dietary and physiological controls on the hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios of hair from mid-20th century indigenous populations. Amer J Phys Anthro. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worton BJ. Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home range studies. Ecology. 1989;70:164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogada DL, Gadd ME, Ostfeld RS, Young TP, Keesing F. Impacts of large herbivorous mammals on bird diversity and abundance in an African savanna. Oecologia. 2008;156:387–397. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-0994-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guldemond R, Van Aarde R. A meta-analysis of the impact of African elephants on savanna vegetation. J Wildlife Management. 2008;72:892–899. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solomon S, et al., editors. IPCC. Regional Climate Projections. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. Ch 11. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Western D. A half a century of habitat change in Amboseli National Park, Kenya. African J Ecol. 2007;45:302–310. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barkham JP, Rainy ME. Vegetation of Samburu-Isiolo game reserve. East Afr Wildlife J. 1976;14:297–329. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowen GJ, Chesson L, Nielson K, Cerling TE, Ehleringer JR. Treatment methods for the determination of δ2H and δ 18O of hair keratin by continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectro. 2005;19:2371–2378. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gehre M, Geilmann H, Richter J, Werner RA, Brand WA. Continuous flow 2H/1H and 18O/16O analysis of water samples with dual inlet precision. Rapid Comm Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2650–2660. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diallo O, Diouf A, Hanan NP, Ndiaye A, Prevost Y. AVHRR monitoring of savanna primary production in Senegal, West Africa. 1987–1988. Int J Remote Sensing. 1991;12:1259–1279. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goward SN, Prince SD. Transient effects of climate on vegetation dynamics: Satellite observations. J Biogeogr. 1995;22:549–564. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borradaile GJ. Statistics of Earth Science Data: Their Distribution in Time, Space and Orientation. Berlin: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trauth MH. MATLAB Recipes for Earth Sciences. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.