Abstract

The intrinsic conformational preferences of Cα,α-dibenzylglycine, a symmetric α,α-dialkylated amino acid bearing two benzyl substituents on the α-carbon atom, have been determined using quantum chemical calculations at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. A total of 46 minimum energy conformations were found for the N-acetyl-N'-methylamide derivative, even though only 9 of them showed a relative energy lower than 5.0 kcal/mol. The latter involves C7, C5 and α' backbone conformations stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds and/or N-H…π interactions. Calculation of the conformational free energies in different environments (gas-phase, carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, methanol and water solutions) indicates that four different minima (two C5 and two C7) are energetically accessible at room temperature in the gas-phase, while in methanol and aqueous solutions one such minimum (C5) becomes the only significant conformation. Comparison with results recently reported for Cα,α-diphenylglycine indicates that substitution of phenyl side groups by benzyl enhances the conformational flexibility leading to (i) a reduction of the strain of the peptide backbone; and (ii) alleviating the repulsive interactions between the π electron density of the phenyl groups and the lone pairs of the carbonyl oxygen atoms.

Introduction

Conformationally restricted α-amino acids are widely used in the construction of peptide analogues with controlled backbone fold. Among the α-amino acids whose structural rigidity can be exploited in the design of restricted peptides are α,α-dialkylated (also called quaternary) amino acids. Tetrasubstitution at Cα introduces severe constraints in the backbone dihedral angles, thus stabilizing particular elements of peptide secondary structure.1,2

The simplest α,α-dialkylated amino acid is α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib), that is, Cα-methylalanine. Replacement of the α-hydrogen in alanine (Ala) by a methyl group results in a drastic reduction of the available conformational space. Theoretical and experimental studies1-4 have demonstrated the strong tendency of Aib to induce folded structures in the 310-/α-helical region (φ, ψ,≈ ±60°,±30°), while semi-extended or fully extended conformations are extremely rare for this residue. In comparison, Ala is easily accommodated in folded or extended structures. For higher homologues of Aib with linear side chains (diethylglycine, dipropylglycine, dibutylglycine, etc.), the stability of helical structures decreases as the side-chain length increases and thus these residues have been shown to prefer fully extended conformations.1,2

We recently investigated the conformational preferences of the Cα,α-diphenylglycine residue (Dϕg) using quantum mechanical calculations.5 Although this residue was crystallized in both the folded and extended conformations depending on the peptide sequence,6 its intrinsic conformational tendencies were established in our recent work.5 Furthermore, the influence of the phenyl side groups on the conformational properties of Dϕg were examined by comparing the minimum energy conformations of this amino acid with those of Aib.

Nine minimum energy conformations were characterized at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level for the N-acetyl-N'-methylamide derivative of Dϕg within a relative energy range of about 9 kcal/mol. The relative stability of these structures was found to be largely influenced by specific backbone…side chain and side chain…side chain interactions that can be attractive (N-H…π and C-H…π) or repulsive (C=O…π). On the other hand, comparison with the minimum energy conformations calculated for Aib, in which the two phenyl substituents are replaced by methyl groups, revealed that the bulky aromatic rings of Dϕg induce strain in the internal geometry of the peptide.

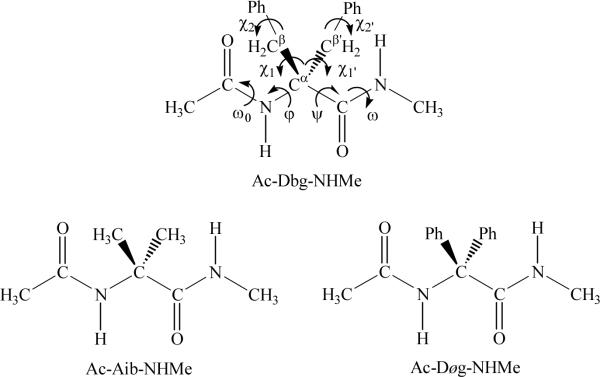

In this work we extend our studies on the intrinsic conformational preferences of symmetrically substituted quaternary amino acids to the Cα,α-dibenzylglycine residue (Dbzg). It should be noted that the methylene groups connected to the Cα are expected to increase significantly the number of minima with respect to Dϕg as well as to decrease the strain induced by the bulky aromatic side groups. Unfortunately, available experimental information about the structural propensities of Dbg is very scarce, a fully extended conformation being detected for some small model peptides.6b,7 In this study,the potential energy surface of the N-acetyl-N'-methylamide derivative of Dbzg (Ac-Dbzg-NHMe, see Figure 1) has been explored using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. The influence of the polarity of the environment on the conformational preferences of this dipeptide has been analyzed using a Self-Consistent Reaction-Field (SCRF) method. Finally, the specific role of the benzyl side groups on the strain of the peptide backbone has been determined by comparing the energetics of the minima found for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe with those of the corresponding Aib and Dϕg analogues (Figure 1) through controlled isodesmic reactions.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the peptides examined in the present work. The minimum energy conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe have been characterized in this study at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level, while the potential energy surfaces of Ac-Aib-NHMe and Ac-Dϕg-NHMe were reported at the same level of theory in reference 5. The backbone and side chain dihedral angles are defined for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe.

Methods

The conformational properties of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe have been investigated using the Gaussian 03 computer program.8 The conformational search was performed considering that this dipeptide retains the restrictions imposed by side-chain methyl groups on the backbone of Ac-Aib-NHMe. Thus, the five minimum energy conformations characterized for Ac-Aib-NHMe in ref. 5 were used to generate the starting structures for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. Although for Ac-Aib-NHMe four of such five minima were twofold degenerate due to the symmetry of the molecule, that is, {φ,ψ}= {-φ,-ψ}, the achiral nature of the Dbzg residue allows maintaining this degeneracy. The arrangement of the benzyl side groups is defined by the flexible dihedral angles {χ1, χ2, χ'1 and χ'2}, which are expected to exhibit three different minima: gauche+ (60°), trans (180°) and gauche- (-60°). The dihedral angles that define the rotation of the amide bonds (ω and ω0) were arranged at 180° in all cases. Consequently, 5 (minima of Ac-Aib-NHMe) × 34 (3 minima for each of the four flexible dihedral angles of benzyl side groups) = 405 minima can be anticipated for the potential energy hypersurface (PEH) E=E(φ,ψ,χ1,χ2,χ'1χ'2 χ of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. All these structures were used as starting points for subsequent full geometry optimizations. This systematic conformational analysis strategy has allowed us to explore the PEHs of both small dipeptides9 and flexible organic molecules.10

All geometry optimizations were performed using the Becke's three parameter hybrid functional (B3)11 combined with the Lee, Yang and Parr (LYP) expression for the nonlocal correlation12 and the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set,13 i.e. B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) calculations. It should be noted that the PEH of both Ac-Aib-NHMe and Ac-Dϕg-NHMe were studied using the same theoretical level.5 Frequency analyses were carried out to verify the nature of the minimum state of all the stationary points obtained and to calculate the zero-point vibrational energies (ZPVE) and both thermal and entropic corrections. These statistical terms were then used to compute the conformational Gibbs free energies in the gas phase at 298 K (ΔGgp).

To obtain an estimation of the solvation effects on the relative stability of the different minima, single point calculations were conducted on the optimized structures using a SCRF model. Specifically, the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) developed by Tomasi and co-workers14 was used to describe carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, methanol and water as solvents. The PCM method represents the polarization of the liquid by a charge density appearing on the surface of the cavity created in the solvent. This cavity is built using a molecular shape algorithm. PCM calculations were performed in the framework of the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level using the standard protocol and considering the dielectric constants of carbon tetrachloride (ε=2.2), chloroform (ε=4.9), methanol (ε=32.6), and water (ε=78.4) to obtain the free energies of solvation (ΔGsolv) of the minimum energy conformations. Within this context, it should be emphasized that previous studies indicated that solute geometry relaxations in solution and single point calculations on the optimized geometries in gas-phase give almost identical ΔGsolv values.15 The conformational free energies in solution (ΔGCCl4, ΔGChl, ΔGMet and ΔGwater) at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level were then estimated using the classical thermodynamics scheme, i.e. summing the ΔGsolv and ΔGgp values.

Results and Discussion

Conformational Properties

Using as starting points the 405 structures described in the Methods section, geometry optimization at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level led to the characterization of 46 different minimum energy structures for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe, which are two-fold degenerate since the structures with {φ,ψ,χ1, χ2,χ'1,χ'2} and {-φ,-ψ,-χ1,-χ2,-χ'1-χ'2} are equivalent and isoenergetic. This indicates that the incorporation of one methylene groups into each side chain of Ac-Dϕg-NHMe produces a significant increase in the peptide flexibility, since only 9 different minima were characterized for the latter dipeptide.

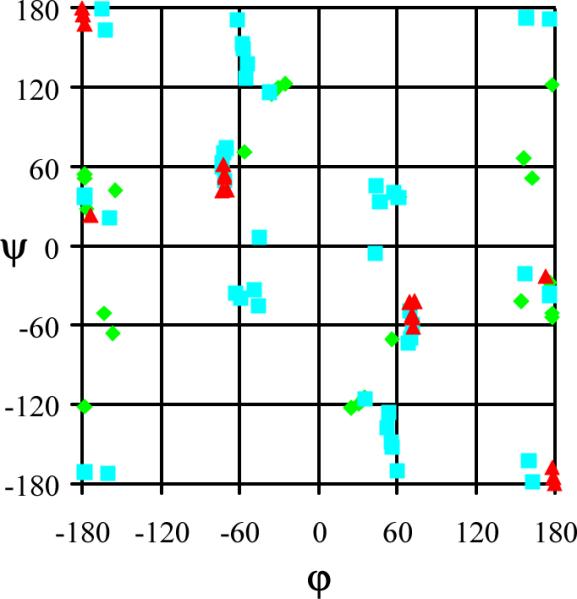

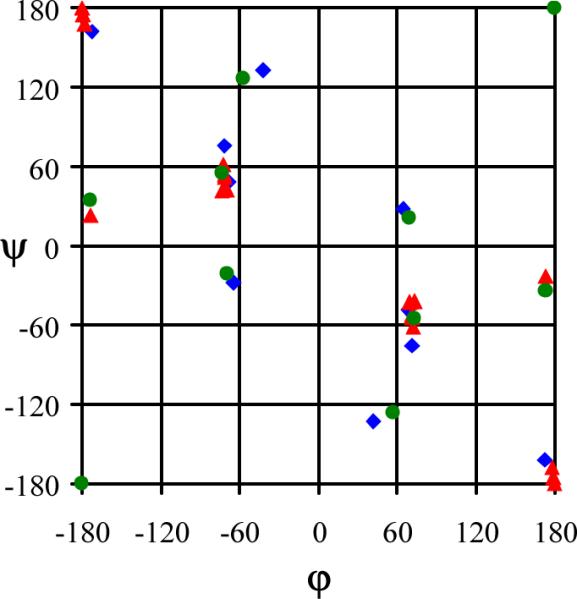

Figure 2 represents the backbone φ,ψ angles of the 46 minima found for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. The backbone conformation of the 9 minimum energy conformations with relative energy lower than 5.0 kcal/mol are categorized within the Ramachandran map as follows: 5 adopts a C7 conformation (seven-membered hydrogen bonded ring) with φ,ψ≈ 60°,-60° or φ,ψ≈ -60°,60°, 3 presents a C5 arrangement (five-membered hydrogen bonded ring) with φ,ψ≈ 180°,180° and only 1 shows an α' conformation with φ,ψ ≈ 180°,±60°. The remaining 37 minima, which also include α (φ,ψ≈ ±60°, ±60°) and PII (φ,ψ≈ ±60°,180°) backbone conformations, have relative energies ranging from 5.0 to 10.0 kcal/mol (25 minima), or even larger (12 minima).

Figure 2.

Backbone conformational preferences predicted for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. Minimum energy conformations with relative energies (ΔE) lower than 5.0 kcal/mol are indicated by red triangles. Blue squares and green diamonds refer to conformations with 5.0 < ΔE < 10 kcal/mol and ΔE ≥ 10 kcal/mol, respectively.

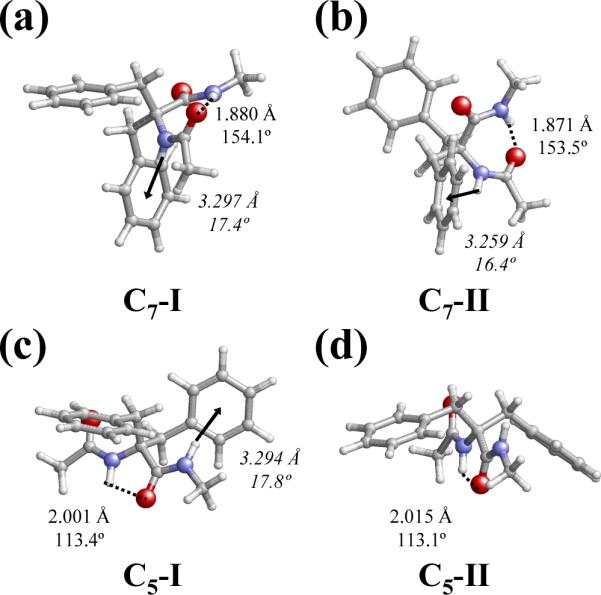

Table 1 lists the backbone and side chain dihedral angles and relative energies (ΔE) of the more representative minimum energy structures of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe in gas-phase, i.e. those with ΔE < 5.0 kcal/mol. In the lowest energy conformation, which has been labeled as C7-I (Table 1), the backbone dihedral angles (φψ= 69.8°,-42.9°) lead to the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the terminal NH and C=O groups [d(H⋯O) = 1.880 Å and <N-H⋯O= 154.1°] defining a seven membered cycle (C7 or γ-turn conformation). This structure, which is displayed in Figure 3a, is also stabilized by an N-H⋯π interaction16 involving the NH group of the Dbzg residue and the π electron density of one of the aromatic side groups. The geometric parameters used to characterize this interaction are: the distance between the NH hydrogen atom and the center of the aromatic ring (dH⋯ring) and the angle defined by the N-H bond and the plane of the aromatic ring (θ). These parameters in the C7-I conformation are dH⋯ring= 3.297 Å and θ= 17.4°. Indeed, N-H···π interactions have been frequently cited as stabilizing factors in the structure of peptides and proteins.17 Furthermore, the intrinsic preferences of different conformationally restricted phenylalanine analogues were found to largely influenced by this specific interaction.4g,8e,f,18

Table 1.

Backbone and Side Chain Dihedral Angles,a Selected Bond Angles (∠N-Cα-C and ∠Cβ-Cα-Cβ')a and Relative Energies in the Gas-Phase (ΔE)b for the More Stable Minimum Energy Conformationsc of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe Characterized at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) Level.

| # | ω0 | φ | ψ | ω | χ1 | χ2 | χ1' | χ2' | ∠N-Cα-C | ∠Cβ-Cα-Cβ' | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7-I | 176.1 | 69.8 | -42.9 | -175.5 | -59.1 | -93.5/88.6 | -45.3 | 102.8/-78.1 | 113.2 | 109.8 | 0.0d |

| C7-II | -175.4 | -71.4 | 52.2 | 179.7 | 42.0 | -102.7/78.3 | 175.0 | 83.4/-98.5 | 111.9 | 109.2 | 1.4 |

| C5-I | 179.2 | 179.3 | -175.6 | -176.1 | 53.8 | 87.0/-94.5 | 177.0 | 99.6/-83.5 | 104.0 | 111.5 | 1.7 |

| C5-II | -179.3 | 179.8 | 178.0 | -179.6 | 54.4 | 86.8/-94.4 | -55.3 | 92.6/-88.6 | 104.2 | 107.8 | 1.8 |

| α' | 169.8 | 173.4 | -23.2 | -172.3 | 60.2 | 93.0/-88.5 | -49.0 | 98.5/-82.5 | 108.7 | 107.7 | 2.9 |

| C5-III | -178.7 | 178.1 | -168.1 | -176.0 | 52.2 | 25.0/-156.7 | 179.5 | 96.7/-85.9 | 104.5 | 110.8 | 3.8 |

| C7-III | -171.3 | -71.5 | 54.4 | 179.9 | -41.2 | 100.0/-81.2 | -171.8 | 91.9/-90.2 | 111.4 | 112.1 | 4.1 |

| C7-IV | -171.8 | -72.7 | 61.8 | -178.3 | -48.7 | 99.3/-82.4 | 171.0 | 42.4/-141.1 | 109.5 | 112.6 | 4.1 |

| C7-V | -176.2 | -73.2 | 41.6 | 173.3 | 46.2 | 78.6/-102.3 | -119.2 | 102.3/-80.5 | 112.8 | 107.5 | 4.6 |

In degrees. See Scheme 1.

In kcal/mol.

Minima with relative energy lower than 5.0 kcal/mol.

E= -997.338908 au.

Figure 3.

C7-I (a), C7-II (b), C5-I (c) and C5-II (d) minimum energy conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe characterized at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. Geometric parameters of both intramolecular hydrogen bonds (dashed lines and roman numbers) and N-H⋯π interactions (arrows and italic numbers) are indicated.

The second minimum, labelled as C7-II (Figure 3b), is almost equivalent to the C7-I structure, i.e. backbone and side chain dihedral angles are very similar but with opposite sign, the only difference being the conformation of one benzyl group (Table 1). Thus, the arrangement of the dihedral angle is gauche and trans for C7-I and C7-II, respectively. However, the two stabilizing interactions found in C7-I are also detected in C7-II: the terminal C=O and N-H groups form an intramolecular hydrogen bond [d(H⋯O) = 1.871 Å and <N-H⋯O = 153.5°], while the N-H moiety of the Dbzg residue is involved in a N-H⋯π interaction [dH⋯Ph = 3.259 Å and θ = 16.4°]. The re-arrangement of one benzyl group produces a destabilization of 1.4 kcal/mol.

In the third minimum, denoted C5-I (Figure 3c), the backbone dihedral angles (φψ= 179.3°,-175.6°) define a five-membered intramolecular hydrogen-bonded ring with parameters d(H⋯O) = 2.001 Å and <N-H⋯O= 113.4°. Furthermore, a N-H⋯π interaction involving the N-H of the NHMe blocking group and one side phenyl group (dH⋯Ph = 3.294 Å and θ = 17.8°) is also detected in this conformation. The fourth minimum, labelled as C5-II, also forms a five-membered intramolecular hydrogen-bonded ring [d(H⋯O) = 2.015 Å and <N-H⋯O= 113.1°]. This minimum only differs from C5-I in the conformation of one side group, this situation being similar to that discussed above for C7-I and C7-II. Interestingly, as can be seen in Figure 3d, the rotation of the dihedral angle precludes the formation of the N-H⋯π interaction in C5-II. Conformations C5-I and C5-II are destabilized by 1.7 and 1.8 kcal/mol, respectively.

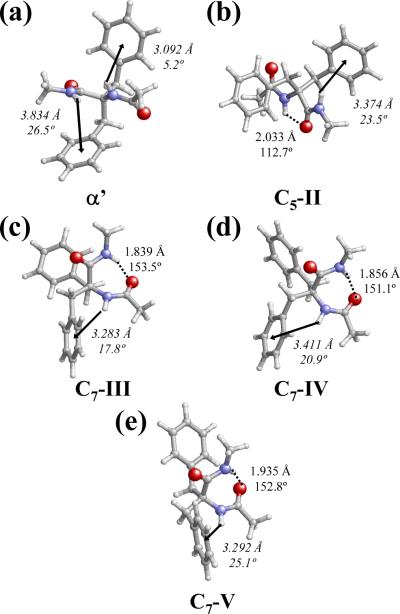

The relative energies of the other five minima listed in Table 1 range from 2.9 to 4.6 kcal/mol and, therefore, their relative population in gas phase is expected to be negligible. In particular, the fifth minimum energy conformation corresponds to a partially folded α' arrangement, which does not show any stabilizing intramolecular hydrogen bond (Figure 4a). Although the relative energy of this structure is relatively high, i.e. 2.9 kcal/mol, the geometrical disposition of the backbone amide groups and the aromatic rings allows the coexistence of two N-H⋯π stabilizing interactions with geometric parameters [dH⋯Ph= 3.834 Å and θ= 26.5°] and [dH⋯Ph= 3.092 Å and θ= 5.2°]. The steric effects produced by the bulky benzyl side groups on the stability of symmetric linear αα-dialkylated amino acids are more important for the remaining minima of Table 1. These four conformations, which have been denoted C5-III, C7-III, C7-IV and C7-V, are depicted in Figures 4b-e. As can be seen, all these structures present both an intramolecular hydrogen bond and an N-H⋯π stabilizing interaction. However, the arrangements adopted by the benzyl side groups lead to strained conformations or involve unfavourable interactions between the lone pairs of the backbone C=O groups and the π-clouds of the aromatic rings. These steric and/or electronic effects produce conformations that are destabilized by more than 3.8 kcal/mol with respect to the global minimum.

Figure 4.

α' (a), C5-III (b), C7-III (c), C7-IV (d) and C7-V (e) minimum energy conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe obtained at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. Geometric parameters of both intramolecular hydrogen bonds (dashed lines and roman numbers) and N-H⋯π interactions (arrows and italic numbers) are indicated.

On the other hand, inspection to the data listed in Table 1 reveals that the ∠N-Cα-C bond angle strongly depends on the backbone conformation. Specifically, for the five C7 conformers the values of the ∠N-Cα-C angle ranges from 109.5° to 113.2°, while it remains close to 104° in the two C5 minima. This conformational dependency is consequence of the geometrical strain induced by the benzyl side groups.

Thermodynamical Corrections and Solvent effects

Table 2 lists the relative conformational Gibbs free energies in gas-phase at T = 298.15 K (ΔGgp) calculated for the nine minima of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe analyzed in the previous section. As can be seen, consideration of the ZPVE, thermal and entropic corrections introduces significant changes to the relative stability of the minima. Specifically, the range that separates the four minima of lower energy, i.e. those with ΔE < 2.0 kcal/mol, is reduced by 0.7 kcal/mol. However, the most remarkable result corresponds to the C5-II minimum, which showed the largest thermodynamical correction transforming into the most stable conformation. Overall, these results indicate that the C5-II, C7-I, C5-I and C7-II are the only energetically accessible minima in gas-phase, i.e. the estimated populations are 63%, 20%, 10% and 7%, respectively, the population expected for the other conformers being negligible.

Table 2.

Relative Conformational Free Energiesa in the Gas-Phase, Carbon Tetrachloride, Chloroform, Methanol and Aqueous Solutions for the More Stable Minimum Energy Conformationsb of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe.

| # | ΔGgp | ΔGcc14 | ΔGchl | ΔGMet | ΔGwater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7-I | 0.7 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 8.9 |

| C7-II | 1.3 | 3.1 | 4.7 | 6.9 | 7.9 |

| C5-I | 1.1 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 5.4 |

| C5-II | 0.0c | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| α' | 2.7 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 6.9 | 5.9 |

| C5-III | 4.9 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 9.2 |

| C7-III | 4.2 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 8.8 | 9.8 |

| C7-IV | 4.0 | 5.6 | 7.1 | 9.5 | 10.6 |

| C7-V | 3.7 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 10.4 | 11.4 |

In kcal/mol.

Minima with relative energy lower than 5.0 kcal/mol in the gas-phase.

E= -997.014910 a.u.

In spite of a large number of works indicated that the influence of the solvent on the ΔGsol of (bio)organic molecules is negligible, we decided to check that this feature is shared by Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. For this purpose, the molecular geometry of the C5-II conformation was re-optimized in both chloroform and water solutions. Comparison of the resulting molecular geometries with that obtained in the gas-phase indicated that the variation of bond distances and bond angles was in all cases lower than 0.008 Å and 2.0°, respectively. Moreover, the values of ΔGsol obtained using the geometries optimized in the gas-phase and in solution were almost identical, i.e. the largest variation was 0.2 kcal/mol. Accordingly, the values ΔGsol in carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, methanol and water were calculated for the minimum energy conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe using the geometries optimized in the gas-phase.

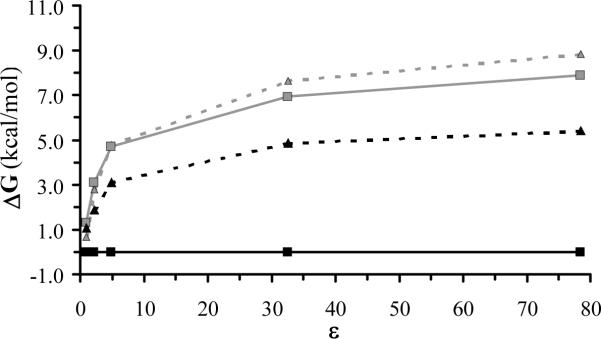

Table 2 also lists the estimated relative conformational free energies calculated in different solvents. As can be seen, solute-solvent interactions do not alter significantly the relative energy order of the different minima with respect to that obtained in the gas-phase. In all cases the C5-II was the lowest energy conformation. Moreover, the relative stability of this structure increases with the polarity of the solvent. This is clearly reflected in Figure 5, which represents the relative conformational free energies calculated for the more stable structures, i.e. C5-II, C7-I, C5-I and C7-II, against the polarity of the environment. The solute-solvent interactions associated with the C5-II conformation become so attractive in solution that it is the only significant structure in chloroform, methanol and aqueous solution. According to a Boltzmann distribution, which is usually used to describe the conformational preferences of small peptides, the population of C5-II at room temperature increases from 63% in gas-phase to 95%, 99%, 100% and 100% in carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, methanol and water solvents, respectively.

Figure 5.

Variation of the conformational free energy against the polarity of the environment for the C5-II (solid black line, black squares), C7-I (dashed gray line, gray triangles), C5-I (dashed black line, black triangles) and C7-II (solid gray line, black triangles) minimum energy conformations.

The overall of the results obtained for Dbzg is in excellent agreement with experimental evidence reported for other αα-dialkylated amino acids.1,2,19 Thus, it has been observed that homopeptides consisting of symmetric αα-dialkylated amino acids with side chains bulkier than a methyl group are able to stabilize a rare secondary structure denoted 2.05 helix. This helical arrangement is based on the propagation of a fully extended conformation that involves a five-membered hydrogen bonded ring. Furthermore, although very scarce, available experimental studies on Dbzg-containing peptides also indicated that the fully extended is the preferred conformation in solution.6b

Influence of the Benzyl Side Groups in the Conformational Properties

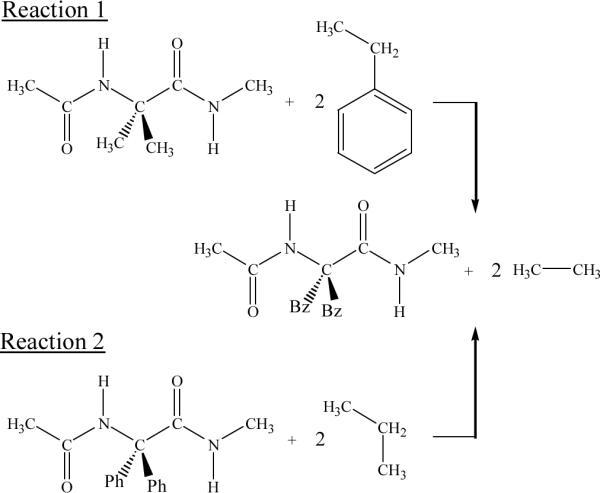

Figure 6 represents the position of all the minima with relative energy lower than 5 kcal/mol characterized at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level for Ac- Dbzg-NHMe, Ac-Dφg-NHMe and Ac-Aib-NHMe. As can be seen, the benzyl side groups restrict significantly the backbone conformation of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. Thus, in spite of the latter dipeptides showing the highest number of low energy minima, only three backbone conformations are detected, i.e. C5, C7 and α'. In contrast, the low energy minima of Ac-Dφg-NHMe and Ac-Aib-NHMe involve four (C5, C7, α and PII) and five backbone conformations (C5, C7, α, PII and α'), respectively.5 Furthermore, it should be noted that when the whole set of energy minima is considered, the relative energy interval is 4.5, 9.8 and 21.4 kcal/mol for Ac-Aib-NHMe, Ac-Dφg-NHMe and Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. Thus, the unfavorable interactions between the backbone and the side groups, which are reflected in the spread out energy spectra, increase with the size of the substituents. On the other hand, our previous study on Ac-Dφg-NHMe and Ac-Aib-NHMe observed that the phenyl in the substituents induce strain in the internal geometry of the peptide.5 In order to quantitatively evaluate the unfavorable interactions and the strain effects induced by benzyl substituents of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe, the isodesmic reactions displayed in Scheme 1 have been considered. For each optimized backbone conformation of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe, the energy associated with the benzyl substituents, GBz/Bz in reactions 1 and 2 was estimated according to Eqns (1) and (2), respectively:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where GAc-Dbzg-NHMe is the free energy of the conformation under study, obtained according to the Boltzmann population of all conformers with such backbone conformation; GAc-Aib-NHMe and GAc-Døg-NHMe correspond to the free energies of the Aib and Døg homologues with similar backbone conformation; and GCH3-CH3 , GCH3-CH2-CH3 and GCH3-CH2-Ph are the free energies of ethane, propane and ethylbenzene, respectively, calculated for the lowest minimum energy conformation at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level.

Figure 6.

Backbone conformational preferences predicted for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe (red triangles), Ac-Dϕg-NHMe (blue diamonds) and Ac-Aib-NHMe (green circles) at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. Only minimum energy conformations with relative energies (ΔE) lower than 5.0 kcal/mol are indicated.

Scheme 1.

In Eqns (1) and (2), GBz/Bz provides an estimation of the energy value associated with the replacement of the methyl (reaction 1 in Scheme 1) and phenyl (reaction 2 in Scheme 1) side groups by benzyl for a given backbone conformation. Results obtained for the C5, C7 and α' backbone conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe described are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Free Energy Contribution Associated with the Benzyl Side Groupsa (GBz/Bz) for the Backbone Conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe in the Gas-Phase and Aqueous Solution.

The positive values of GBz/Bz derived from reaction 1 and Eqn (1) reveal significant unfavorable effects for all backbone conformations in both gas phase and aqueous solution, even though these are significantly lower in the latter environment. On the basis of our previous study on Ac-Døg-NHMe and Ac-Aib-NHMe,5 this is an expected result that should be attributed to two different factors: First, the strain induced by the benzyl groups of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe in the internal geometry of the peptide. In addition, substitution of methyl by benzyl introduces the possibility of repulsive interactions between the π electron density of the phenyl groups and the lone pairs of the oxygen atoms contained in the backbone carbonyl groups. The strength of such unfavorable interactions is reduced considerably in aqueous solution for backbone conformations in which the oxygen atoms show a higher accessibility to the surrounding solvent, i.e. C5 and α'.

On the other hand, all GBz/Bz values obtained from reaction 2 and Eqn (2) are negative illustrating that the unfavorable effects induced by the side groups are considerably higher in Ac-Døg-NHMe than in Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. This is because the conformational flexibility of the benzyl groups is higher than that of the phenyl ones, which contributes to reduce both the backbone strain and the repulsive electronic interactions induced by the side chains of Ac-Døg-NHMe. The reduction of the strain is indicated when comparing the ∠N-Cα-C and ∠Cβ-Cα-Cβ bond angles for the minimum energy conformations of Ac-Døg-NHMe5 and Ac-Dbzg-NHMe (Table 1). The deviation with respect to the value ideally expected for these bond angles, i.e. 109.5°, is lower for the three backbone conformations of Ac-Dbzg-NHMe than for Ac-Døg-NHMe. Furthermore, it is worth noting that GBz/Bz is notably lower in aqueous solution than in the gas phase, indicating than the benzyl side groups allows a more favorable interaction with the peptide backbone than the phenyl ones. This can be also justified by the higher conformational flexibility of the former with respect to the latter.

Conclusions

DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level have been used to analyze the conformational preferences of the Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. A total of 46 different minimum energy conformations, which are stabilized by attractive backbone⋯backbone (hydrogen bonds) and backbone⋯side chain (N-H⋯π) interactions, have been identified. However, only nine such minima showed a relative energy lower than 5 kcal/mol. The conformational free energies have been calculated in five different environments. The results showed that four different minima, which correspond to C5 and C7 backbone conformations, are energetically accessible at room temperature. However, the energy of three such minima increases rapidly with the polarity of the environment, a structure with a C5 backbone conformation being the only significant minimum (population=100%) in both methanol and aqueous solutions.

Comparison with the results previously reported for Ac-Aib-NHMe and Ac-Døg-NHMe at the same level of theory has provided information about the effects produced by the side chain. Specifically, substitution of the methyl side groups of Ac-Aib-NHMe by benzyl produces, as expected, unfavorable strain effects in the internal geometry of the peptide and repulsive interactions between the π-aromatic rings and the carbonyl oxygen atoms. In contrast, these two effects are significantly reduced when the phenyl side groups of Ac-Døg-NHMe are replaced by benzyl, which should be attributed to the higher conformational flexibility of the latter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to the Centre de Supercomputació de Catalunya (CESCA) and to the Universitat de Lleida for computational facilities. This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the view of the policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Coordinates and energy of the minimum energy conformations characterized for Ac-Dbzg-NHMe. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).(a) Toniolo C, Formaggio F, Kaptein B, Broxterman QB. Synlett. 2006:1295. [Google Scholar]; (b) Venkatraman J, Shankaramma SC, Balaram P. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3131. doi: 10.1021/cr000053z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C. Biopolymers (Pept. Sci.) 2001;60:396. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<396::AID-BIP10184>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Kaul R, Balaram P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:105. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Benedetti E. Biopolymers (Pept. Sci.) 1996;40:3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0282(1996)40:1<3::aid-bip2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Toniolo C, Benedetti E. Macromolecules. 1991;24:4004. [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Karle IL, Baralam P. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6747. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Karle IL, Flippen-Anderson JL, Uma K, Balaram P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pavone V, Di Blasio B, Santini A, Benedetti E, Pedone C, Toniolo C, Crisma M. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;214:633. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90279-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Karle IL, Flippen-Anderson JL, Uma K, Balaram H, Balaram P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Prasad BVV, Balaram P. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1984;16:307. doi: 10.3109/10409238409108718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Improta R, Rega N, Alemán C, Barone V. Macromolecules. 2001;34:7550. [Google Scholar]; (c) Alemán C. Biopolymers. 1994;34:841. [Google Scholar]; (d) Huston SE, Marshall GR. Biopolymers. 1994;34:75. doi: 10.1002/bip.360340109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang L, Hermans J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:11915. [Google Scholar]; (f) Alemán C, Roca R, Luque FJ, Orozco M. Proteins. 1997;28:83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Alemán C, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Pérez JJ, Casanovas J. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:11849. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Casanovas J, Zanuy D, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:2174–2181. doi: 10.1021/jo0624905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Pavone V, Lombardi A, Saviano M, Di Blasio B, Nastri F, Fattorusso R, Zaccaron L, Maglio O, Yamada T, Omote Y, Kuwatam S. Biopolymers. 1994;34:1595. doi: 10.1002/bip.360341204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Crisma M, Valle G, Bonora GM, Toniolo C, Lelj F, Barone V, Fraternali F, Hardy PM, Maia HLS. Biopolymers. 1991;31:637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Toniolo C, Crisma M, Fabiano N, Melchiorri P, Negri L, Krause JA, Eggleston DS. Int. J. Pept. Prot. Res. 1994;44:85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1994.tb00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Valle G, Crisma M, Bonora GM, Toniolo C, Lelj F, Barone V, Fraternalli F, Hardy PM, Langran-Goldsmith A, Maja HLS. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2. 1990:1481. [Google Scholar]; (b) Damodharan L, Pattabhi V, Behera M, Kotha S. Acta Crystallogr. 2004;C60:0527. doi: 10.1107/S0108270104013150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Vreven T, Jr., Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, C. Strain M, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh PA: 2003. Gaussian 03, Revision B.02. [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Alemán C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:5046. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gómez-Catalán J, Alemán C, Pérez JJ. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2000;103:380. [Google Scholar]; (c) Casanovas J, Zanuy D, Nussinov R, Alemán C. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006;429:558. doi: 10.1021/jp062804s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Alemán C, Zanuy D, Casanovas J, Cativiela C, Nussinov J. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:21264. doi: 10.1021/jp062804s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Casanovas J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Pérez JJ, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7088. doi: 10.1021/jo034720a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Casanovas J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Pérez JJ, Alemán C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5762. doi: 10.1021/jp0542569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Alemán C, Casanovas J, Zanuy D, Hall HK., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:2950. doi: 10.1021/jo0478407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alemán C, Casanovas J, Hall HK., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7731. doi: 10.1021/jo051167j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1372. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).McLean AD, Chandler GS. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:5639. [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Miertus S, Scrocco E, Tomasi J. Chem. Phys. 1981;55:117. [Google Scholar]; (b) Miertus S, Tomasi J. Chem. Phys. 1982;65:239. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tomasi J, Persico M. Chem. Phys. 1994;94:2027. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tomasi J, Mennucci B, Cammi R. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Hawkins GD, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3257. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jang YH, Goddard WA, III, Noyes KT, Sowers LC, Hwang S, Chung DS. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:344. [Google Scholar]; (c) Iribarren JI, Casanovas J, Zanuy D, Alemán C. Chem. Phys. 2004;302:77. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Desiraju GR, Steiner T. The Weak Hydrogen Bond in Stuctural Chemistry and Biology. Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Steiner T, Koellner G. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:535. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Worth GA, Wade RC. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:17473. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mitchell JBO, Nandi CL, McDonald IK, Thornton JM. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;239:315. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mitchell JBO, Nandi CL, Ali S, McDonald IK, Thornton JM. Nature. 1993;366:413. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Casanovas J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:644. doi: 10.1021/jo702107s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Di Blasio B, Pavone V, Lombardi A, Pedone C, Benedetti E. Biopolymers. 1993;33:1037. doi: 10.1002/bip.360330706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Benedetti E, Pedone C, Pavone V, Di Blasio B, Saviano M, Fattorusso R, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Bonora GM, Toniolo C, Kaczmarek K, Redlinski AS, Leplawy MT. Biopolymers. 1994;34:1409. doi: 10.1002/bip.360341012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.