Abstract

According to attachment theory, attachment security or attachment style derives from social experiences that begin early in life and continue into the adult years. In this study we examined these expectations by examining associations between the quality of observed interaction patterns in the family of origin during adolescence and self-reported romantic attachment style and observed romantic relationship behaviors in adulthood (at ages 25 and 27). Family and romantic relationship interactions were rated by trained observers from video recordings of structured conversation tasks. Attachment style was assessed with items from Griffin and Bartholomew's (1994) Relationship Scales Questionnaire. Observational ratings of warmth and sensitivity in family interactions were positively related to similar behaviors by romantic partners and to self-reported attachment security. In addition, romantic interactions characterized by high warmth and low hostility at age 25 predicted greater attachment security at 27, after controlling for attachment security at age 25. However, attachment security at age 25 did not predict later romantic relationship interactions after controlling for earlier interactions. These findings underscore the importance of social experiences in close relationships for the development of romantic attachment security but they are inconsistent with the theoretical expectation that attachment security will predict the quality of interactions in romantic unions.

Beginning with Bowlby's (1969/1982) seminal theoretical work, the study of attachment has progressed along two fairly independent trajectories (described by Simpson & Rholes, 1998, and Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). One line of research has focused on the attachment relationship between child and parent, primarily in infancy but also as late as adolescence (e.g., Allen & Land, 1999). The other line of research has focused on the attachment dynamics of adult romantic and marital relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003, 2007). The present report focuses on self-reported romantic attachment security in adult romantic relationships and the degree to which it is linked to experiences in attachment relationships with parents and romantic partners (e.g., Bartholomew, 1990; Bretherton & Munholland, 1999).

Mikulincer and Shaver (2003, 2007) have summarized much of the research on attachment processes in terms of a three-component model of what Bowlby (1969/1982) called the attachment behavioral system. According to this model, threats activate the attachment system and cause a person to notice the presence or absence (“availability” and “responsiveness”) of a security-providing attachment figure. If no such figure is perceived to be available and responsive, the person has to make an explicit or implicit decision to hyperactivate or deactivate the attachment system. Over time, a person's experiences in such situations alter and shape the parameters of the attachment system, making either security-based strategies or hyperactivating (anxious) or deactivating (avoidant) strategies more likely. Attachment theory, then, proposes that when attachment relationships involve behaviors that are responsive, sensitive, caring and available, the person in such a relationship is more likely to develop a secure rather than insecure attachment style. Attachment relationships without these behavioral characteristics should lead to greater insecurity in attachment.

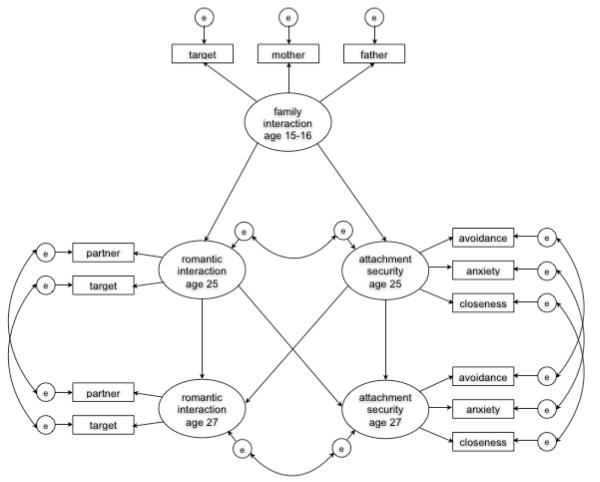

Despite this theoretical interest in social-relational sources of attachment security, there is little evidence concerning the developmental origins of romantic attachment styles because most studies of adult romantic attachment begin with people who are already college students or mature adults. Moreover, there is relatively little research combining behavioral observations of parent-child and romantic interactions with self-reports of attachment style. The purpose of the present study is three-fold: (1) to examine the contribution of the quality of family interactions during adolescence to later romantic attachment styles and the quality of romantic interactions in adulthood, (2) to examine the contribution of romantic relationship interactions to subsequent romantic attachment style, and (3) to assess the degree to which romantic attachment style predicts the quality of behavioral interactions in romantic relationships. Figure 1 provides a schematic for the conceptual model which guides the study. The next sections consider the theoretical and empirical bases for each of the predicted associations in the proposed model.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model for the study.

Influence of Parents on Romantic Relationships and Attachment Representations

Parent-Child Interactions and Attachment Representations

According to Mikulincer and Shaver (2003, 2007), attachment working models established in infancy and childhood, mostly in relationships with parents and other key caregivers, should form the foundation for attachment representations throughout life. In Figure 1, this expectation is illustrated by the path from interactions in the family during adolescence to attachment security at 25 years of age. Because, as mentioned, research on romantic attachment patterns began with adolescent or adult samples of people who were already involved in romantic or marital relationships (Hazan & Shaver, 1987), the hypothesized origins of self-reported romantic attachment styles in previous relationships with parents have been largely taken on faith rather than being empirically tested.

Parents and other primary caregivers are theoretically responsible for the initial shaping of attachment representations, and this influence has been examined in scores of empirical studies with young children (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Thompson, 1999; Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999). There is also evidence of parental influence on adult attachment as measured with the AAI (Hamilton, 2000; Weinfield et al., 2000). In his 2002 meta-analysis, Fraley found evidence for a “prototype” model of attachment, which suggested that attachment patterns are shaped by the family of origin in early childhood and these patterns continue to exert a substantial influence over the years. Consistent with this idea, a recent study by Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that one's attachment orientation in infancy predicted the emotional quality of romantic relationships in early adulthood, and that this association was mediated by social competency in elementary school and secure or insecure friendships in adolescence. Especially important, the Simpson et al. longitudinal study suggests that the influence of parent-child attachment on subsequent romantic relationship functioning is indirect and dependent on important personal relationships outside the nuclear family.

Although there is considerable evidence that parents play an important role in shaping children's attachment patterns, at least in relation to parents, there is little research exploring how parents influence romantic attachment styles or working models, and the little research that does exist (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007, Chapter 3) suffers from significant methodological limitations. For example, using a cross-sectional design, Steinberg, Davila, and Fincham (2006) found that attachment insecurity mediated the association between perceptions of parental conflict and negative romantic experiences and marital expectations. Jones, Forehand, and Beach (2000) found that adolescents' evaluations of parental behavior predicted self-reported attachment security approximately 5 years later, an association that may include common-method bias. The present study overcomes some of these earlier methodological limitations.

Parent-Child Interactions and Later Romantic Interactions

Researchers have explored behavioral consistencies between parent-child relationships and later romantic relationships. For example, based on both behavioral and self-report data collected across a 15-year span, Conger, Cui, Bryant, and Elder (2000) concluded that there is a significant association between the child-parent relationship and adult romantic relationship functioning. Behavioral observations of interactions between parents and their early adolescent child predicted important features of the child's interactions with his or her romantic relationship partner during early adulthood, as illustrated by the path in Figure 1 from family interactions to interactions with a romantic partner at 25 years of age. Conger et al.'s research did not focus, however, on psychological processes that might account for this relationship.

Other researchers have found that poor marital adjustment is associated with earlier difficulties in relationships with parents (e.g., Truan, Herscovitch, & Lohrenz, 1987). Researchers have explored whether this association might be a result of the fact that individuals who had poor-quality relationships with parents also had parents whose relationship with each other was troubled. If so, the offspring might have acquired poor interaction skills through observational learning. Counting against this possibility is the fact that general parental aggression toward a child, but not interparental aggression, predicts subsequent poor relationship functioning, even after controlling for personality traits (Kennedy, Bolger, & Shrout, 2002).

Most research on the link between child-parent relationships and later romantic relationships relies on the AAI (Hesse, 1999; George et al., 1996). This measure, which focuses on an adult's discussion of his or her childhood relationships with parents, is typically given in adulthood, so its association with romantic relationship behavior is concurrent rather than prospective. The evidence produced by research with the AAI, however, is consistent with our prediction that parent-child relationship quality as assessed through observed behavioral exchanges will predict later interactions with a romantic partner. For example, Bouthillier et al. (2002) used the AAI to assess “state of mind with respect to attachment” (Main et al., 1985) to mother and found that individuals who were categorized by the AAI as insecure were more likely to use destructive tactics during a conflictual interaction with a romantic partner. In addition, individuals categorized as insecure in the AAI exhibited more negative emotion during conflictual interactions (i.e., more expressions of contempt, withdrawal, and stonewalling) and less positive emotion (e.g., Babcock et al., 2000; Creasey & Ladd, 2005; Roisman et al., 2005; Roisman et al., 2001). Because attachment security as assessed by the AAI likely derives to a significant degree from the quality of the parent-child relationship in terms of behavioral interactions, these findings offer indirect support for the proposition that this relationship will affect the behavioral quality of later romantic unions. The present study directly examines behavioral interactions both in the family of origin and in adult romantic relationships.

Hypotheses Regarding Family of Origin Influences

Overall, existing research suggests that the nature of the parent-child relationship influences subsequent romantic relationships, and that there is a small association between parent-child attachment representations and romantic attachment representations. In addition, because parent-child interactions are associated with attachment security during childhood, there is reason to believe that parent-child interactions should predict attachment security in children and adolescents grown to adulthood. Based on this theoretical reasoning and findings from previous research, we hypothesized that, in the present longitudinal study of a cohort of adolescents making the transition to adulthood, family interactions marked by high levels of warmth, caring, and sensitivity and low levels of hostility and coercion would predict similar behavior toward an adult romantic partner and greater security in self-reported attachment representations at 25 years of age (Hypothesis 1). Further, we predicted that the influence of family interactions on attachment style would decrease as participants continued in longer, more serious, romantic relationships, because these relationships would shape attachment patterns independently of the effects of parents' behavior (Hypothesis 2). That is, family influences on later relationship behaviors and attachment security at 27 years of age were expected to be indirect through earlier levels on these domains. These expectations are illustrated in Figure 1.

Influence of Romantic Relationships on Romantic Attachment Style

Fraley and Davis (1997) suggested that the transfer of primary attachment status from parents to peers begins in late adolescence or early adulthood, which is beyond the time period addressed in most longitudinal studies. This proposed mechanism suggests that as peers, and eventually romantic partners, begin to assume the role of primary attachment figures, relationships with these individuals should influence attachment representations just as parents once did. Mikulincer and Shaver (2003, 2007) also note that later relationships may change attachment style and move it away from its original form. Feeney (2004) found evidence for this transfer. In a sample of young adults, greater romantic involvement was associated with stronger attachment to partners and weaker attachment to mothers and friends. In addition, strength of attachment was a function of participant age and length and closeness of romantic relationship.

There is, however, little research exploring the direct influence of romantic partners on attachment style. Using the original categorical measure of romantic attachment, Kirkpatrick and Hazan (1994) found that romantic attachment stability was moderated by break-up or initiation of romantic relationships across a 4-year period. Individuals who ended relationships during the 4-year period tended to become less secure, and those who began relationships tended to become more secure. Using growth curve modeling, Davila, Karney, and Bradbury (1999) found that over the first two years of marriage one spouse's level of attachment security can influence the other spouse's level of attachment security. There was also a reciprocal influence of marital satisfaction on attachment security, such that increased levels of marital satisfaction led to increased attachment security, and vice versa. These findings indicate that romantic partners influence attachment style and that relationship satisfaction may play a role in the process.

To address this issue, we investigated the degree to which the quality of behavioral interactions in romantic relationships predicts romantic attachment style. Specifically, given that romantic partners are likely, gradually, to become primary attachment figures, we hypothesized that interactions in romantic relationships marked by high levels of warmth, caring, and sensitivity and low levels of hostility and coercion would increase attachment security over time (Hypothesis 3), as illustrated by the path in Figure 1 from romantic interactions at age 25 to attachment security at age 27.

Influence of Romantic Attachment Style on Romantic Relationships

Numerous studies have found an association between an individual's self-reported attachment style and his or her behavior in romantic relationships. Both attachment anxiety and avoidance have been associated with a variety of negative romantic relationship behaviors. For example, attachment-anxious individuals show lower levels of enjoyment in interactions with romantic partners and fewer proximity-seeking behaviors in these interactions (Tucker and Anders, 1998). Attachment-anxious individuals were also more likely to exhibit distress and use less successful discussion tactics during discussions of a major disagreement with a dating partner (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005; Guerrero, 1996; Simpson, Rholes, & Phillips, 1996). In interactions with romantic partners, individuals who were high on attachment avoidance made less eye contact, exhibited less overall pleasantness, and were rated as being less interested in and attentive to their romantic partner (Guerrero, 1996). In addition, attachment-avoidant individuals showed lower levels of positive behavior (e.g, laughing, smiling, physical contact, eye contact) (Tucker and Anders, 1998). Similarly, couples who rated themselves, as a dyad, to be higher in attachment avoidance, displayed less expressive nonverbal behavior (Le Poire, Shepard, and Duggan, 1999).

Based on these findings and the basic tenets of attachment theory, we hypothesized that attachment security at age 25 will predict romantic interactions characterized by high levels of warmth, caring, and sensitivity and low levels of hostility at age 27 (Hypothesis 4), as illustrated in Figure 1. Taken together, hypotheses 3 and 4 predict that attachment security and the quality of interactions between romantic partners will be reciprocally interrelated over time.

Because both married and cohabiting or dating couples were included in the present study, we tested our final model for differences between these types of relationships. Previous research (e.g., Cupach & Metts, 1986; Stafford, 1990; Stafford & Canary, 1991) indicated that married couples differ from cohabiting or dating couples in a variety of ways (e.g., perception of communication quality and relationship problems, attributions of responsibility, relationship maintenance attempts and strategies). Therefore, it was important to see if the kind of relationship influenced the hypothesized associations between the variables of interest.

Methods

Participants

The study is based on data from the Family Transitions Project, which builds on two earlier studies of adolescents and their families: the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP) and the Iowa Single Parent Project (ISPP) (see Cui, Conger, Bryant, & Elder, 2002, for a review). The adolescent participants, originally recruited in 1989 with two-parent families for the IYFP, were all in 7th grade in 1989. In 1991 the ISPP began recruiting children from the same cohort (adolescents in 1991 were in 9th grade) from single-parent, mother-headed families. The present study uses data from both 1991 samples, omitting the IYFP data from 1989 and 1990, when only one kind of family was sampled. The resulting sample size for target adolescents is N = 559, including 294 females and 265 males. The families in both projects were recruited from rural Iowa as part of a larger project designed to study family economic stress. The ethnic/racial background of the participants and their families was predominantly Caucasian, which reflects the demographics of rural Iowa. Participants and their families were interviewed in their homes on multiple occasions as the target participants moved through adolescence. In later adolescence and adulthood, participants were interviewed with a romantic or marital partner in their own homes.

For the present analyses only targets with a romantic partner were included in the analyses. The specific nature of these relationships is described later in this section. Of the participants used in the present analyses, at age 15, 206 were interviewed with both mother and father, 46 were interviewed with mother only. At age 16, 190 were interviewed with both mother and father, 56 participants were interviewed with mother only. In subsequently discussed path models the missing data for fathers from single-parent families was estimated using Full Information Maximum Likelihood.

Measures and Procedures

Interactions in the family of origin

From 1991 to 1994 participants and their families were interviewed in their homes. For this study we used information on behavioral interactions between parents and adolescents obtained in 1991 and 1992. The series of component interviews and assessments included two structured, videotaped interactions. Both interactions were designed to elicit both positive and negative emotion from each of the family members. The observational interactions centered on questions about family life and issues of concern that led to disagreement. Videotaped interactions were rated by trained observers using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby & Conger, 2001). All observers received 200 hours of training (20 hours per week for 10 weeks) and passed extensive reliability tests before coding taped interactions. To ensure continued reliability, coders attended maintenance training sessions each week. A second observer independently rated 25% of all videotapes to assess interobserver reliability which was assessed using intraclass correlations.1

Consistent with procedures used in earlier reports from this program of research (Conger et al., 2000; Donnellan, Larsen-Rife, & Conger, 2005), the following scales assessed each family member's behavior toward each of the other family members: angry coercion, which reflects attempts to change the behavior or ideas of others in a hostile, threatening, or blaming manner; antisocial, which reflects the expression of insensitivity, lack of caring, or defiance; hostility, which reflects the expression of anger, criticism, disapproval, or rejection; positive communication, which assesses the individual's ability to convey his or her ideas, opinions, needs, and wants in a clear, positive, or neutral manner; listener responsiveness, which assesses the individual's attention to, interest in, and acknowledgement of others; prosocial behavior, which reflects the tendency to relate in a cooperative, sensitive, and helpful manner; warmth/support, which reflects expression of caring, affection, affirmation, and support; and positive assertiveness, which assesses the individual's ability to express ideas and opinions in a positive manner. Behavioral ratings were made on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (little evidence of the attribute in question) to 9 (a great deal of evidence for the attribute in question). Observers were instructed to take both the frequency and the intensity of a behavior into account when scoring the interactions.

Because the summed items for negative interactions were highly and negatively correlated with the summed scale for positive behaviors, we followed the same procedures as in earlier reports from this study and created a single scale (Conger et al., 2000; Donnellan et al., 2005). Although these scales can be combined to reflect either high hostility and low warmth or the reverse, in this study they were combined to reflect high positive and low negative behaviors, consistent with study hypotheses. Specifically, the ratings for angry coercion, antisocial behavior, and hostility were reverse coded and summed with the ratings of positive behaviors. A reliable positive behavior scale was created for each family member (i.e., mother to target, α = .88; father to target, α = .88; and target to mother and father, α = .92) by averaging each individual's scores on the eight aforementioned scales for both interactions in 1991 and 1992, when participants were 15 and 16 years old, respectively. Interobserver reliability for the individual ratings ranged from .69 to .94. Behavioral observations were averaged across ages 15 and 16 to represent the average ratings of the different observers who rated the interactions for each wave of data. Therefore, the scales represent the average of positive behaviors for each individual across two tasks and over a two-year time period. (See Table 1 for correlations between mother, father, and target positive behaviors at each time point.) As noted earlier, FIML was used to estimate values for missing data from fathers. In path models (described in the Results section) these three scales were used to create a latent variable called family interactions at age 15-16.

Table 1.

Correlations Among Family Interaction Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. target to mother age 15 | - | .88 | .66 | .64 | .66 | .52 | .53 | .45 |

| 2. target to father age 15 | - | .62 | .69 | .52 | .46 | .62 | .46 | |

| 3. target to mother age 16 | - | .85 | .50 | .70 | .44 | .51 | ||

| 4. target to father age 16 | - | .45 | .58 | .50 | .58 | |||

| 5. mother to target age 15 | - | .66 | .56 | .50 | ||||

| 6. mother to target age 16 | - | .52 | .58 | |||||

| 7. father to target age 15 | - | .71 | ||||||

| 8. father to target age 16 | - | |||||||

Note. N = 267; all coefficients are significant at the p < .01 level, two-tailed.

Romantic partner interactions

Starting in 1995, and continuing every other year (i.e., in 1997, 1999, 2001, and 2003), participants were interviewed with a romantic partner (or, in 1995 and 1997, with a close friend if they were not involved in a romantic relationship). For the present study, data from 2001 and 2003 were used to capture interactions at the oldest ages at which romantic-relationship data were collected. In 2001 and 2003, target participants were 25 and 27 years old, respectively. This decision allowed for the largest sample of participants in the same romantic relationships at any two consecutive time points. At age 25, of the 474 targets who were interviewed, 45 participated with a dating partner, 71 with a cohabiting partner, 239 with a spouse, and 119 with no partner. At age 27, of the 450 targets who were interviewed, 20 participated with a dating partner, 49 with a cohabiting partner, 269 with a spouse, and 112 with no partner. For present purposes, only those with the same romantic or marital partner at both ages were included in the analyses, because this allowed us to assess possible effects of the relationship on attachment style over time (N = 269, 157 females and 112 males). At age 27, 241 were married, 21 were cohabiting, and 7 were in dating relationships. Married participants had been married for an average 3.71 years, cohabiting partners had known their partners for an average of 4.16 years, and dating partners had known their partners for an average of 3.24 years. In other words, these were generally stable long-term relationships.

In each wave of data collection, participants and their partners completed videotaped interactions in which they discussed the history and status of their relationship, areas of agreement and disagreement in the relationship, and plans for the future. These interactions were designed to elicit both positive and negative relationship behaviors. Interactions were rated independently and reliably by trained observers using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby & Conger, 2001), following the same procedures described earlier for family interactions. The same scales used for the family interactions were used to code the romantic partner interactions: partner to target positive behavior (α = .90 for age 25, α = .88 for age 27), target to partner positive behavior (α = .90 for age 25, α = .90 for age 27). Interobserver reliability ranged from .84 to .88. For use in later path models (described in the Results section), partner to target and target to partner scales from each year were used as indicators for a latent variable called romantic interaction at age 25 and romantic interaction at age 27.

Target self-report measures of romantic attachment representations

In 2001 and 2003, when target participants averaged 25 and 27 years of age, respectively, self-reported attachment style was assessed using Griffin and Bartholomew's (1994) Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ). The RSQ was originally designed to provide multi-item assessment of four attachment styles that Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) had previously measured with only one item per style. The four style subscales proved to have fairly low internal consistency reliabilities, but the set of items is nevertheless useful for assessing broad factors underlying adolescent and adult attachment styles, such as anxiety, comfort with closeness, and comfort with dependency (Collins & Read, 1990).

The following reliable scales were created from the RSQ items: anxiety, based on items assessing anxiety in romantic relationships (e.g., “I often worry that romantic partners won't want to stay with me”); closeness, assessing ability and desire to maintain close and intimate relationships (e.g., “I find it easy to get emotionally close to a romantic partner”); and avoidance, assessing discomfort with close relationships (e.g., “I prefer not to have a romantic partner depend on me”). The factor structure of the items in the aforementioned scales was determined first using exploratory maximum likelihood factor analysis with promax rotation in SPSS. The first three factors (i.e., anxiety, avoidance, and closeness) were similar at both time points, and their meaning was similar to the meaning of Collins and Read's (1990) frequently used three attachment-style scales. This factor structure was then verified through confirmatory factor analysis in AMOS. The models fit the data adequately at age 25 (χ2 = 538.96, df = 116, Δχ2/Δdf = 4.65, RMSEA = .08, CFI = .92) and age 27 (χ2 = 647.55, df = 116, Δχ2/Δdf = 5.58, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .89). (For a more detailed discussion of the creation of these scales see Nitzberg, 2006.)

The scales were reliable at each time point (anxiety, α = .90 at age 25, and α = .90 at age 27; closeness, age 25, α = .91, age 27, α = .90; avoidance, age 25, α = .83, age 27, α = .80). For present purposes all scales were scored in the secure, or positive, direction, and when used in path models (described in the Results section) the three scales from each year were used as indicators of latent variables called attachment security at age 25 and attachment security at age 27.

Results

Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

Means and standard deviations for measured variables were calculated (Table 2). Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine mean level change in variables between ages 25 and 27. These analyses show that partner positive behavior to target increased significantly from age 25 to age 27, F(1, 250) = 35.96, p < .001, and target positive behavior to partner increased significantly from age 25 to age 27, F(1, 250) = 38.16, p < .001. However, no significant changes from age 25 to age 27 were found in target anxiety, F(1, 265) = 2.62, p = .11, avoidance, F(1, 264) = .68, p = .41, or closeness, F(1, 265) = 1.79, p = .18. This result indicates that, while the target participants' and their partners' behavior became more positive over time, attachment style did not generally change in mean level.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for All Measured Variables

| Variable |

M |

SD |

N |

|---|---|---|---|

| target to parents | 4.34 | 1.12 | 240 |

| mother to target | 5.34 | 1.07 | 238 |

| father to target | 5.34 | 1.04 | 191 |

| partner to target age 25 | 5.96 | 1.34 | 256 |

| target to partner age 25 | 5.87 | 1.34 | 256 |

| anxiety age 25 | 4.41 | .64 | 266 |

| closeness age 25 | 3.80 | .81 | 266 |

| avoidance age 25 | 4.68 | .56 | 266 |

| partner to target age 27 | 6.39 | 1.24 | 253 |

| target to partner age 27 | 6.30 | 1.30 | 253 |

| anxiety age 27 | 4.48 | .65 | 267 |

| closeness age 27 | 3.86 | .81 | 267 |

| avoidance age 27 | 4.71 | .51 | 266 |

Correlations among all manifest variables described in the previous section are reported in Table 3. As predicted by Hypothesis 1, family interaction variables were significantly correlated with all of the behavioral interaction variables and the majority of attachment indicators at both 25 and 27 years of age. For example, mother's behavior significantly predicted target behavior to a romantic partner at age 25 (r = .29, p < .01). It is important to note that both parent-to-target and target-to-parent variables were significantly correlated with the attachment variables. This is relevant to subsequent path model analyses because father-to-target, mother-to-target, and target-to-parent variables all contribute to a single family interaction latent variable. Based on significant correlations between parent behavior to target and target attachment, a significant path from the family interaction variable to the attachment security variable cannot be interpreted as being based solely on target behavior. That is, this path results from the behavior of the family interaction influencing target attachment security, not just enduring qualities of the target affecting both family interactions and later attachment security. Similarly, both target-to-romantic-partner and romantic-partner-to-target behavior variables were correlated with target attachment variables. Especially important, couple interactions at age 25 predicted attachment style at age 27 and attachment style at age 25 predicted couple interactions at age 27, consistent with the reciprocity hypotheses 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Behavioral and Attachment Security Measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Target Behavior to Parents | - | .69* | .63* | .32* | .18* | .41* | .24* | .19* | .15 | .15 | .13* | .13* | .14* |

| 2. Mother Behavior to Target | - | .63* | .29* | .17* | .36* | .27* | .16* | .05 | .12 | .13* | .09 | .12 | |

| 3. Father Behavior to Target | - | .37* | .23* | .41* | .32* | .21* | .21* | .21* | .11 | .15* | .15* | ||

| 4. Target to Partner age 25 | - | .72* | .65* | .47* | .18* | .32* | .27* | .23* | .33* | .30* | |||

| 5. Partner to Target age 25 | - | .50* | .60* | .16* | .26* | .20* | .20* | .22* | .21* | ||||

| 6. Target to Partner age 27 | - | .70* | .31* | .32* | .26* | .18* | .33* | .21* | |||||

| 7. Partner to Target age 27 | - | .23* | .20* | .14 | .55* | .20* | .18* | ||||||

| 8. Anxiety age 25 | - | .33* | .56* | .64* | .25* | .35* | |||||||

| 9. Closeness age 25 | - | .60* | .31* | .60* | .45* | ||||||||

| 10. Avoidance age 25 | - | .34* | .39* | .55* | |||||||||

| 11. Anxiety age 27 | - | .33* | .56* | ||||||||||

| 12. Closeness age 27 | - | .58* | |||||||||||

| 13. Avoidance age 27 | - |

p < .01, two-tailed, based on N = 267.

Structural Equation Analyses

Structural equation models were first estimated allowing paths among variables to vary across type of relationship, married versus not married. Then the paths were constrained to be equal and the models were re-estimated. The results were not significantly different whether the path coefficients were left free to vary or constrained to be equal (Δχ2 = 11.23, df = 7, p = .13). Therefore, we concluded that there were no differences in the findings by type of relationship and the results described below pertain to the combined sample of relationship types.

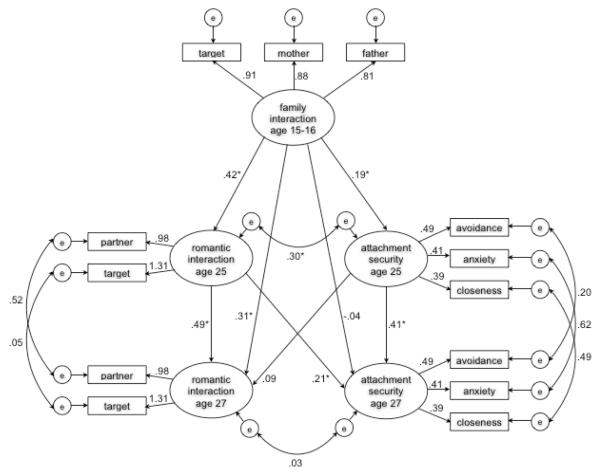

To test the four major hypotheses, a path model was constructed using Mplus 5.0 (Figure 2). Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation was used, given the presence of some missing data for certain participants. Specifically, father data was estimated for the 46 participants interviewed with mother only at age 15, and 56 at age 16. The model was specified in the following fashion: (a) the Family Interaction at Age 15-16 latent variable was identified by fixing the latent variable variance to unity, (b) nonlinear constraints were invoked so that the variances of the Romantic Interaction at Age 25 and Attachment Security at Age 25 latent variables were constrained to unity, and (c) the scales of the Romantic Interaction at Age 27 and Attachment Security at Age 27 latent variables were identified by constraining all factor loadings for these latent variables to be invariant across the two measurement occasions. The constraints under (b) above were made so that cross-lagged regression paths across time between Romantic Interaction and Attachment Security would be on the same scale and comparisons of these coefficients would be valid. In addition, the unique variances for repeated manifest variables (e.g., avoidance at age 25 and avoidance at age 27) were constrained to equality, consistent with common approaches to factorial invariance across time (Widaman & Reise, 1997). In addition, paths were added from Family Interaction at Age 15-16 to Attachment Security at Age 27 and Romantic Interaction at Age 27 in order to test for mediation in subsequent analyses.

Figure 2.

SEM findings related to the conceptual model; * p < .05

The model (Figure 2) fit the data adequately, χ2 (58, N = 267) = 97.83, Δχ2/Δdf = 1.69, RMSEA = .051, CFI = .974). All factor loadings reported in Figure 2 are in covariance metric. The loadings of target (.91), mother (.88), and father (.81) indicators on the Family Interaction latent variable correspond to standardized loadings of .82, .82, and .77, respectively. The loadings of the partner and target manifest variables on the Romantic Interaction latent variables, .98 and 1.31, respectively, correspond to standardized factor loadings of .75 and .97, respectively. The loadings of avoidance (.49), anxiety (.41), and closeness (.39) on the Attachment Security latent variables translate into standardized factor loadings of .63, .49, and .89, respectively. Thus, factor loadings on all latent variables represent moderate to quite strong loadings. In addition, Romantic Interaction was relatively stable from age 25 to age 27 (β = .49, SE = .06, p < .001), as was Attachment Security (β = .41, SE = .07, p < .001).

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, Family Interactions at Ages 15-16 significantly predicted Romantic Interaction at Age 25 (β = .42, SE = .06, p < .001) and Attachment Security at age 25 (β = .19,, SE = .08, p < .05). Inconsistent with Hypothesis 2 was the finding that Family Interactions were a significant predictor of Romantic Interactions at Age 27 (β = .31, SE = .06, p < .001). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, Family Interactions did not directly predict Attachment Security at Age 27 (β = −.04, SE = .08, p = .54). When the paths from Family Interactions to Attachment Security at Age 25 and to Attachment Security at Age 27 were constrained to be equal, this significantly decreased the overall fit of the model, Δχ2 = 4.22, df = 1, p < .05, indicating support for Hypothesis 2 that Family Interactions are indirectly related to Attachment Security at age 27 through their earlier association with Attachment Security at age 25. We also tested for indirect effects and found that the indirect effect from Family Interactions to Attachment Security at Age 27 through Attachment Security at Age 25 was statistically significant, indirect effect = .08, SE = .03, p < .05. In addition, the indirect effect from Family Interaction to Attachment Security at Age 27 through Romantic Interaction at Age 25 was also significant, indirect effect = .09, SE = .03, p < .01.

As mentioned previously, Family Interaction had a direct influence on Romantic Interaction at Age 27. Family Interaction also had an indirect influence on Romantic Interaction at Age 27 through Romantic Interaction at Age 25, indirect effect = .20, SE = .04, p < .001. However, the indirect effect from Family Interaction to Romantic Interaction at Age 27 through Attachment Security at Age 25 was small and nonsignificant, indirect effect = .02, SE = .02, ns.

Reflecting Hypotheses 3 and 4, the reciprocal cross-lagged paths between Romantic Interaction and Attachment Security from Age 25 to 27 were next evaluated. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, the path from Romantic Interactions at Age 25 to Attachment Security at Age 27 was significant, β = .21, SE = .07, p < .01). In contrast, the direct effect across time between Attachment Security at Age 25 and Romantic Interaction at Age 27 (Hypothesis 4) was rather small and nonsignificant, β = .09, SE = .06, p = .11.

Discussion

The overall goal of this study was to test whether the quality of parent-child interactions in adolescence and romantic partner interactions in early adulthood contributed to attachment style. Overall, we found support for positive parent-child interactions at ages 15 and 16 predicting attachment security at age 25. Parent-child interactions did not make a unique contribution at age 27, but did make an indirect contribution through both romantic interaction and attachment security at age 25. In addition, positive romantic interactions at age 25 contributed significantly to attachment security at age 27. Thus, it seems that both the family of origin and subsequent romantic relationships affect attachment representations. More importantly, as romantic relationships persist and most likely become more serious, the direct influence of the family of origin decreases, and in this case ceases entirely, as romantic interactions begin to influence attachment style. This suggests that while there is an initial direct influence of family interactions on attachment security, this influence lessens over time and romantic partner interactions begin to have an influence of their own. It is important to note that family interactions indirectly influence later attachment security through earlier influence on romantic interactions and attachment security. Essentially, the association between family interactions and attachment security later in life is fully mediated by earlier security and romantic interactions.

Taken together, the findings suggest, in line with attachment theory, that one contributor to a young adult's romantic attachment style is behavioral interactions with parents during adolescence. Although the path from family interactions to attachment security was not large, it was statistically significant. Moreover, the interaction measure was based on behavioral coding and the attachment-style measure was based on participants' self-reports of feelings and reactions in romantic relationships. These two assessments are quite different in method and focus. What stands out, therefore, is the fact that there was a significant association between the two measures across a 9 to 10 year period of time. These findings support those from earlier studies based on less conservative measurement strategies that may have inflated the association between parental behaviors and offspring attachment style. To our knowledge, these findings provide the first evidence that the observed quality of parent-child interactions during adolescence directly predict attachment style in the middle 20s. As such, they provide an important and critical test of attachment theory in relation to romantic ties.

The results also are compatible with a model of attachment in which later relationships can alter at least conscious attachment representations based on earlier attachment relationships. This is different from Fraley's (2002) “prototype” model, which suggested that attachment patterns early in childhood continue to exert a substantial influence over the years. This difference may be a result of Fraley's (2002) meta-analysis focusing primarily on studies running from infancy to late adolescence and predicting AAI classifications (based on an interview focused on child-parent relationship history) rather than mental representations of attachment in peer or romantic relationships. The present study indicates that as participants enter serious romantic or marital relationships, their romantic/marital interactions begin to influence their attachment style, especially when attachment style is measured with respect to such relationships (rather than memories of childhood relationships with parents, as assessed in the AAI). Somewhat echoing Fraley's “prototype” model, however, there was high stability of attachment security between ages 25 and 27, and self-reported attachment security at age 25 was significantly influenced by qualities of the parent-child relationship measured behaviorally 9-10 years earlier. Thus, although parents may not have had additional influence beyond early adulthood, their influence on early adult attachment styles continued. Our findings are also compatible with the model supported empirically by Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007), which portrayed the link between infant attachment security and positive emotional quality of romantic relationships as mediated by secure attachment relationships with friends in adolescence. Both that study and ours suggest that romantic attachment style is related to childhood experiences but can change all along the way as a function of security- and insecurity-inducing experiences in close relationships.

Contrary to our conceptual model, however, attachment security at age 25 did not predict romantic interactions at age 27. This finding is inconsistent with the hypothesis that attachment style in relation to romantic unions will affect the behavior of self and/or partner (e.g., Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). We expect that the methodological rigor of the present study may help account for the difference in results compared to earlier research. That is, our test of the proposition that attachment style would predict couple interactions was prospective. Earlier studies tended to look only at the association between attachment style and couple interactions at the same point in time (e.g., Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005; Simpson, Rholes, & Phillips, 1996; Tucker & Anders, 1998), a research strategy less able to evaluate the direction of hypothesized effects. In any case, the present findings clearly demonstrate the significance of behavioral interactions in close relations in predicting romantic attachment security. The results are not consistent with the hypothesis that attachment security will predict the quality of later interactions in romantic relationships.

Limitations and Future Directions

Because the data used in this study were not originally intended to assess family interactions and attachment style in infancy or childhood, the earliest assessments of participants' interactions with family members for the combined cohort were made at age 15. It would be ideal to conduct a study from early infancy through adulthood to determine the extent to which family dynamics change over time and influence later romantic interactions and attachment style. Moreover, as the Iowa Family Transitions Project continues to follow the group of participants studied here, it will be important to examine lasting relationships to see whether our findings are consistent across longer time spans. In addition, it would be ideal for future research to rely on more current measures of attachment (e.g., the Experiences in Close Relationships inventory; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998).

Despite the limitations of this study, it makes an important contribution to our understanding of the developmental trajectory of romantic attachment. It suggests that romantic attachment is based on early parent-child interactions and is also influenced by subsequent romantic relationships. It will be important in future research to pursue related questions. For example, we need to identify the extent to which parent-child relationship and early romantic attachment representations influence partner selection. If secure family relationships increase the likelihood of choosing more secure partners, this would suggest that partner attachment mediates the association between secure family relationships and romantic attachment security. Additionally, it would be useful in future studies to obtain self-report measures of relationship satisfaction, to see whether they are distinct from attachment security or wrapped up with it, and whether satisfaction precedes changes in attachment security. In the present study, we lack details of the process mediating positive interactions and changes in attachment style.

Finally, we suggest that future research explore the role that the target individual plays in shaping family interactions, and therefore his or her own attachment security and romantic relationship interactions. The models discussed in the present article include all family members and both relationship partners rather than exploring the unique contribution made by parents or romantic partners. This is because the observed interactions were designed to assess how all members of a family or relationship communicated with one another, rather than isolating the contributions of a particular individual. Future research may further refine understanding by exploring specific individual contributions to these processes. And important method for pursuing this research strategy would be through the use of the social relations model (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), a statistical procedure for disentangling actor and partner effects on social interaction. At present, we can only make the best of an existing data set that already has many advantages over the much more common studies involving only self-reports collected at a single point in time.

In short, the present research provides empirical support that positive interactions in family and romantic relationship contribute to secure attachment representations while negative interactions in these relationships contribute to insecure representations. This information is critical to understanding both the initial development of and subsequent changes in attachment security.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/fam/.

A complete description of all ratings and task procedures, along with scale definitions, can be obtained from Rand D. Conger, Department of Human and Community Development, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 95616.

References

- Ainsworth MS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP. The attachment system in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. 2nd edition. Guilford Press; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Yerington TP. Attachment, emotional regulation, and the function of marital violence: Differences between secure, preoccupied, and dismissing violent and nonviolent husbands. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K. Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:147–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokhorst CL, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Fearon R, van IJzendoorn MH, Fonagy P, Schuengel C. The importance of shared environment in mother-infant attachment security: A behavioral genetic study. Child Development. 2003;74:1769–1782. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthillier D, Julien D, Dube M, Belanger I, Hamelin M. Predictive validity of adult attachment measures in relation to emotion regulation behaviors in marital interactions. Journal of Adult Development. 2002;9:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Hogarth; London: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52:664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Brussoni MJ, Jang KL, Livesley WJ, MacBeth TM. Genetic and environmental influences on adult attachment styles. Personal Relationships. 2000;7:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson J, Boldry J, Kashy DA. Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:510–531. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant C, Elder GH., Jr. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TN, Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Shaver PR, Cohen P, Ganiban J. Insecure attachment and personality disorder: A twin study of adults. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G, Ladd A. Generalized and specific attachment representations: Unique and interactive roles in predicting conflict behaviors in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:1026–1038. doi: 10.1177/0146167204274096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Treboux D, Waters E. The adult attachment interview and the relationship questionnaire: Relations to reports of mothers and partners. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Conger RD, Bryant CM, Elder GH., Jr. Parental behavior and the quality of adolescent friendships: A social contextual perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:676–689. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Cobb RJ. Predicting change in self-reported and interviewer-assessed adult attachment: Tests of the individual difference and life stress models of attachment change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:859–870. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029007005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Attachment change processes in the early years of marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:783–802. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S. Mother-Father-Peer Scale. University of Massachusetts; Amherst: 1987. Unpublished research instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC. A secure base: Responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel D, Wille DE, Matheny AP. Preliminary results from a twin study of infant-caregiver attachment. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:1–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1021448429653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC. Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Davis KE. Attachment formation and transfer in young adults' close friendships and romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Adult Attachment Interview protocol. 3rd ed. University of California; Berkeley: 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK. Attachment-style differences in intimacy and involvement: A test of the four category model. Communication Monographs. 1996;63:269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. The metaphysics of measurement: The case of adult attachment. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman DP, editors. Advances in personal relationships: Attachment processes in adult relationships. Vol. 5. Jessica Kingsley; London: 1994. pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CE. Continuity and discontinuity of attachment from infancy through adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71:690–694. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. The adult attachment interview: Historical and current perspectives. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 395–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Beach SRH. Maternal and paternal parenting during adolescence: Forecasting early adult psychological adjustment. Adolescence. 2000;35:513–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JK, Bolger N, Shrout PE. Witnessing interpersonal psychological aggression in childhood: Implications for daily conflict in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:1051–1077. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, Hazan C. Attachment styles and close relationships: A four-year prospective study. Personal Relationships. 1994;1:123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Hazan C. Attachment in marriage: Effects of security and accuracy of working models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:861–869. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.6.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poire BA, Shepard C, Duggan A. Nonverbal involvement, expressiveness, and pleasantness as predicted by parental and partner attachment style. Communication Monographs. 1999;66:293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observation coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Ge X, Conger RD, Warner TD. The importance of task in evaluating positive marital interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:981–994. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 35. Academic Press; New York: 2003. pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzberg RE. Romantic attachment development: The stability of attachment representations and the influence of parents and romantic partners. University of California; Davis: 2006. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TG, Croft CM. A twin study of attachment in preschool children. Child Development. 2001;72:1501–1511. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Collins AW, Sroufe AL, Egeland B. Predictors of young adults' representations and behavior in their current romantic relationships: Prospective test of the prototype hypothesis. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:105–121. doi: 10.1080/14616730500134928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Fraley RC. The limits of genetic influence: A behavior-genetic analysis of infant-caregiver relationship quality and temperament. Child Development. 2006;77:1656–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Madsen SD, Hennighausen KH, Collins WA. The coherence of dyadic behavior across parent-child and romantic relationships as mediated by the internalized representation of experience. Attachment and Human Development. 2001;3:156–172. doi: 10.1080/14616730126483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senchak M, Leonard KE. Attachment styles and marital adjustment among newlywed couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Belsky J, Brennan KA. Comparing measures of adult attachment: An examination of interview and self-report methods. Personal Relationships. 2000;7:25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:133–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, Haydon KC. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes SW, Phillips D. Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:899–914. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg S, Davila J, Fincham F. Adolescent marital expectations and romantic experiences: Associations with perceptions about parental conflict and adolescent attachment security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Early attachment and later development. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Truan GS, Herscovitch J, Lohrenz JG. The relationship of childhood experience to the quality of marriage. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;32:87–92. doi: 10.1177/070674378703200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Anders SL. Adult attachment style and nonverbal closeness in dating couples. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 1998;22:109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Child Development. 2000;71:695–702. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Sroufe AL, Egeland B, Carlson EA. The nature of individual differences in infant-caregiver attachment. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Reise SR. Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substance use domain. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG, editors. The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance use research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1997. pp. 281–324. [Google Scholar]