Abstract

Cancer patients treated with antimitotic drugs in the taxane and vinca alkaloid classes sometimes develop a chronic painful peripheral neuropathy whose cause is not understood. In animal models of painful peripheral neuropathy due to nerve trauma or diabetes there is obvious axonal degeneration accompanied by an abnormal incidence of spontaneous discharge in A-fiber and C-fiber nociceptors. But animals with paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked neuropathic pain do not have axonal degeneration at the level of the peripheral nerve. However, recent data show that they do have a partial degeneration of the primary afferent neurons’ terminal arbors in the epidermis. It is not clear as to whether this relatively minor degeneration is accompanied by abnormal spontaneous discharge. We surveyed primary afferent axonal activity in the sural nerve of rats with the paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked pain syndromes at the time of peak pain severity. Compared to vehicle-injected controls, we find a significant increase in spontaneously discharging A-fibers and C-fibers. Moreover, we show that prophylactic treatment with acetyl-l-carnitine (ALC), which blocks the development of the paclitaxel-evoked pain, causes a significant decrease (ca. 50%) in the incidence of A-fibers and C-fibers with spontaneous discharge. These results suggest that abnormal spontaneous afferent discharge is likely to be a factor in the pathogenesis of chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy, and that the therapeutic effects of ALC may be due to the suppression of this discharge.

Keywords: Allodynia, Chemotherapy, Hyperalgesia, Neuropathy, Pain, Paclitaxel, Vincristine

1. Introduction

Neurotoxicity is the dose-limiting side-effect for chemotherapeutics in the taxane and vinca alkaloid classes, and in many cases the nerve damage is accompanied by a chronic painful peripheral neuropathy (Uhm and Yung, 1999; Verstappen et al., 2003; Dougherty et al., 2004; Cata et al., 2006b). There are no validated means for the prevention or treatment of the pain syndrome and its cause is not understood.

Electrophysiological experiments in rats with painful peripheral neuropathy due to several kinds of nerve trauma and due to diabetes have detected a clearly abnormal incidence of spontaneously discharging primary afferent sensory neurons, including presumptive A-fiber and C-fiber nociceptors (e.g., Burchiel et al., 1985; Kajander and Bennett, 1992; Kajander et al., 1992; Wu et al., 2002). Spontaneous nociceptor discharge is believed to give rise to spontaneous pain sensations and to engage central mechanisms that contribute to abnormal stimulus-evoked pain sensations such as allodynia and hyperalgesia (Woolf and Thompson, 1991; Gracely et al., 1992; Devor and Seltzer, 1999; Djouhri et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2006).

Unlike painful peripheral neuropathies due to trauma and diabetes, pain in paclitaxel-treated and vincristine-treated rats occurs in the absence of axonal degeneration in peripheral nerves (Tanner et al., 1998a; Topp et al., 2000; Polomano et al., 2001; Flatters and Bennett, 2006). However, we have recently shown that there is degeneration that is confined to the intraepidermal sensory terminal arbors in rats with paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked pain (Siau et al., 2006). This degeneration may lead to spontaneous discharge.

We have hypothesized that the fundamental pathology for paclitaxel-evoked neuropathic pain is a toxic effect on axonal mitochondria (Flatters and Bennett, 2006). The effects of mitochondrial toxicity will be expressed most strongly in regions of high metabolic demand, where mitochondria are concentrated (reviewed in Chang et al., 2006). Primary afferent sensory terminals are likely to be regions of high metabolic demand and it has been shown that the terminals of some sensory afferents contain an unusually high concentration of mitochondria (Heppelmann et al., 1994, 2001). Impaired mitochondrial function suggests that there might be an energy deficit that compromises the neuron’s ability to operate ion transporters. This would lead to membrane depolarization and the generation of spontaneous action potentials. Recent evidence suggests that treatment with acetyl-l-carnitine (ALC), an agent known to ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction (Virmani et al., 2005; Zanelli et al., 2005), prevents and reverses chemotherapy-evoked pain in rats (Ghirardi et al., 2005a,b; Flatters et al., 2006).

Our goal here was to determine whether abnormal spontaneous activity was present in primary afferent neurons in rats with confirmed paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked pain. In addition, we explored whether the beneficial effect of ALC treatment in paclitaxel-treated rats was associated with an effect on the incidence of abnormal spontaneous discharge.

2. Methods

These experiments conformed to the ethics guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain (Zimmermann, 1983), the National Institutes of Health (USA) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and to the regulations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, McGill University.

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Inc.; Indianapolis, IN; Frederick, Maryland breeding colony; 250–350 g) were housed on sawdust bedding in plastic cages. Artificial lighting was provided on a fixed 12 h light–dark cycle; food and water available ad libitum.

2.2. Paclitaxel and vincristine treatment

Paclitaxel (Taxol®; Bristol-Myers-Squibb; 6 mg/ml in a 50:50 mixture of ethanol and Cremophor) was diluted with saline to a concentration of 2 mg/ml and injected IP (2 mg/kg) on four alternate days (D0, D2, D4, and D6) as described previously (Flatters and Bennett, 2004). Control animals received injections of an equal volume of the vehicle. Vincristine (Novopharm Ltd, Toronto, ON, Canada) was diluted with distilled water to a concentration of 50 µg/ml. Animals were injected IP with 50 µg/kg for 10 consecutive days as described previously (Siau and Bennett, 2006).

2.3. Behavioral measures

For each animal, post-paclitaxel and post-vincristine tests with 4 and 15 g von Frey hairs were performed to confirm the presence of chemotherapy-evoked mechano-allodynia (increased response frequency to the 4 g stimulus) and mechano-hyperalgesia (increased response frequency to the 15 g stimulus) 1–2 days prior to the electrophysiological studies. Behavioral testing methods are described in detail elsewhere (Flatters and Bennett, 2004; Xiao et al., 2007).

2.4. Electrophysiological studies

Animals were prepared for electrophysiological recordings at the approximate time of peak symptom severity: D28–D55 for paclitaxel-treated animals (n = 5) and their vehicle-injected controls (n = 5), and D15–D23 for vincristine-treated animals (n = 4). An additional group (n = 5) of naïve animals was also examined; these rats received no injections and no behavioral tests.

Using sodium pentobarbital (55 mg/kg, IP) anesthesia, rats were prepared with an endotracheal tube and a cannula in the jugular vein. The animals were subsequently placed on a respirator and anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in oxygen (1%; 200 ml/min). Areflexia was maintained with the IV administration of pancuronium bromide (1.0 mg/kg/h). Endtidal CO2 was monitored continuously and kept within physiological limits by adjusting the rate and volume of respiration. Subcutaneous needle electrodes were placed on both sides of the thorax and the ECG was monitored continuously. Core temperature was monitored with a rectal thermode and maintained at 37–38 °C via a feedback-controlled heating pad beneath the animal. Care was taken to keep the hind paw warm; this minimizes the possibility of confusing the ongoing discharge of cooling-specific afferents with chemotherapy-evoked spontaneous discharge. An adequate depth of anesthesia was inferred from the absence of heart rate change after pinching the tail and by the absence of a pinch-evoked tail flick prior to the administration of neuromuscular blockade.

The sural nerve was exposed in the popliteal fossa, transected, and submerged in a pool of warm mineral oil formed from raised skin flaps. Subcutaneous needle electrodes were inserted across the lateral surface of the ankle for stimulation of sural afferent axons innervating the hind paw. Microfilaments were dissected from the distal end of the transected sural nerve and draped over a silver-wire hook electrode that was referenced to a needle electrode inserted in adjacent muscle. This arrangement records axonal activity originating in the periphery. Action potentials were amplified, band-pass filtered, led to an audio amplifier and to a PC-interfaced A-D converter, displayed on a video monitor for on-line analysis, digitized and recorded for off-line analysis (Spike2 software; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK).

Data were collected by an experimenter who was blind as to whether the animal had received drug or control injections. For each microfilament the procedure was as follows. First the recording was monitored for 5 min. If fibers with spontaneous discharge were present, they were identified by their waveform and the pattern and frequency of the discharge were recorded. We defined spontaneous discharge as all activity greater than 1 impulse/min (Ali et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2002). Second, the skin in the sural nerve’s territory was stimulated, first with light touch (brushing the skin with an artist’s brush) and then with noxious squeezing of skin folds with flat-tipped forceps, to determine whether the spontaneous active fibers had receptive fields on the glabrous skin. Spontaneously active fibers that did not respond to touch or squeezing were discarded from the tally of spontaneously active fibers. Third, the sural nerve was stimulated at the ankle with shocks (1.0 Hz; 0.1 ms pulse duration for A-fibers, 1.0 ms duration for C-fibers) of gradually increasing intensity. Unit responses of fixed latency and threshold were counted to ascertain the number of individually-identifiable A-fibers and C-fibers that were present in the microfilament. We then computed the percentage of fibers with spontaneous discharge relative to the total number of individually-identifiable fibers in the microfilament (Govrin-Lippmann and Devor, 1978). Conduction velocities were computed from the latency of response and the distance between the recording and stimulating electrodes (measured by placing a thread along the course of the nerve). Fibers were classified according to their conduction velocity (CV) as myelinated A-fibers (CV greater than 2.0 m/s) or unmyelinated C-fibers (CV less than 2.0 m/s) (Djouhri and Lawson, 2004).

Our goal was a survey of spontaneous discharge. We purposely avoided thorough characterization of the responses to natural stimuli for the fibers with spontaneous discharge and made no attempt to find the receptive fields of the other individually-identifiable fibers that were present in the microfilament. We did this because characterizing nociceptors requires the repeated application of high intensity heat or mechanical stimuli that may cause primary afferent sensitization, which itself generates “spontaneous” (or ongoing) discharge. We concentrated our attention on spontaneously active fibers that responded to stimulation of the glabrous skin. Our data on paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked changes in the epidermal innervation (Siau et al., 2006) come from examinations of this region, and patients with chemotherapy-evoked pain report pain particularly in the glabrous skin of the palms of the hands and the soles of the foot (Dougherty et al., 2004).

2.5. Acetyl-l-carnitine study

To test the effects of ALC, groups of rats were randomly assigned to receive paclitaxel plus 21 daily doses of ACL (100 mg/kg, IP; starting on the same day as paclitaxel administration) or paclitaxel plus 21 daily doses of an equal volume (1.0 ml/kg) of vehicle. Behavioral tests were done prior to paclitaxel administration and on days 25, 26 and 27 afterwards. We have previously shown that this ALC treatment paradigm results in a significant inhibition of the paclitaxel-evoked pain syndrome that lasts for at least 17 days after the last dose of ALC (Flatters et al., 2006). ALC and vehicle-injected control animals were prepared for electrophysiological recordings on D30–38 and data were collected by an experimenter who was blind as to whether the animals had received ALC or control injections.

2.6. Statistics

Differences between groups in the incidence of spontaneous discharge were evaluated by the χ2 statistic with p < 0.05 considered significant. Other between-group comparisons used unpaired two-tailed t-tests.

3. Results

3.1. Spontaneous activity in naïve and vehicle-injected control animals

We recorded 122 A-fibers and 37 C-fibers from 35 microfilaments in naïve rats and 157 A-fibers and 52 C-fibers from 42 microfilaments in vehicle-injected rats. None of the C-fibers had spontaneous discharge. In the naïve group 1/122 A-fibers (CV: 30 m/s) had spontaneous discharge; in the vehicle-injected group 2/157 A-fibers (CVs: 26 and 28 m/s) had spontaneous discharge. For the combined naïve and vehicle-injected control groups, the incidence of spontaneous discharge was thus 0% for C-fibers and 1.0% for A-fibers.

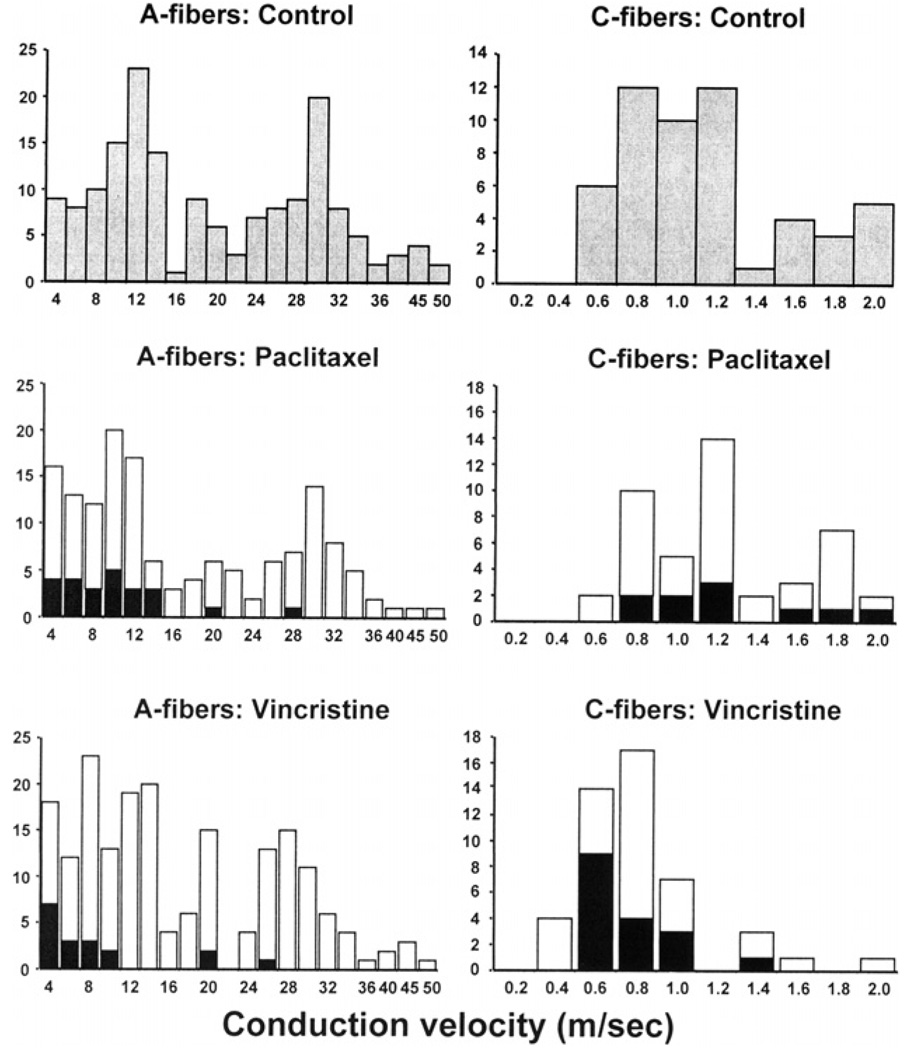

The CV distributions of all the fibers in the vehicle-injected control group are shown in Fig. 1. The A-fiber distribution was bimodal with peaks at approximately 11 and 30 m/s. The C-fiber distribution was unimodal with mean (±SD) of 1.1 ± 0.4 m/s.

Fig. 1.

Conduction velocity distributions for A-fibers (left column) and C-fibers (right column) in the vehicle-injected control, paclitaxel-treated, and vincristine-treated groups. In the bottom two rows, fibers with spontaneous discharge are shown as filled columns; those without spontaneous discharge are shown as open columns.

3.2. Spontaneous activity in animals treated with paclitaxel

We recorded 150 A-fibers and 45 C-fibers from 38 microfilaments in animals with paclitaxel-evoked pain. Seventeen percent (25/150) of the A-fibers had spontaneous discharge and 20% (9/45) of the C-fibers had spontaneous discharge. The incidence of spontaneous discharge in A- and C-fibers was significantly greater (p < 0.01) than that seen in the control rats. Responses to noxious squeezing of a skin fold were found in 71% of the spontaneously active A-fibers and 83% of the C-fibers, the remaining fibers responded only to brushing the skin.

The CV distributions for all fibers recorded from paclitaxel-treated rats are shown in Fig. 1. The distributions of A-fiber and C-fiber CVs were comparable to those seen in the control animals. A-fibers with spontaneous discharge had CVs that were generally among the slowest of the A-fibers. The mean CV value for the spontaneously active A-fibers (10.2 ± 6.8 m/s) was significantly slower (p < 0.01) than that of A-fibers that did not have spontaneous discharge fibers (17.4 ± 11.1 m/s). The C-fibers had a mean CV of 1.15 ± 0.4 m/s, which was not significantly different from the control group. There was no significant difference between the mean CVs of the C-fibers that had spontaneous discharge and those that did not.

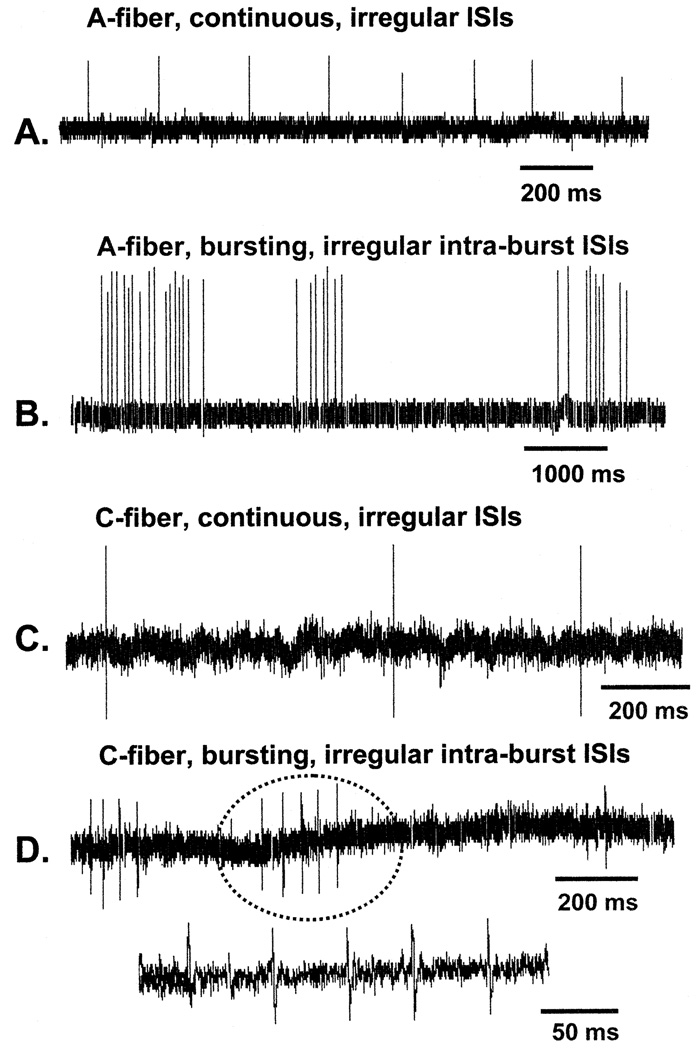

The A-fiber spontaneous discharge had a mean frequency of 1.6 ± 1.9 Hz (range: 0.03–5.9 Hz) and the pattern of the discharge was either continuous (22/25) with irregular interspike intervals (ISIs) or bursting (3/25) with irregular intra-burst ISIs. The C-fiber spontaneous discharge had a mean frequency of 1.6 ± 0.5 Hz (range: 0.4–2.0 Hz) and the pattern of the discharge was either continuous (8/9) with irregular ISIs or bursting (1/9) with irregular intra-burst ISIs. Specimen recordings are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Examples of spontaneously discharging fibers in paclitaxel-treated (A, B, and D) and vincristine-treated (C) rats. ISIs: interspike intervals. The burst of C-fiber discharges circled in (D) is shown with an expanded time base below.

3.3. Spontaneous activity in animals treated with vincristine

We recorded 184 A-fibers and 47 C-fibers from 38 microfilaments in rats with vincristine-evoked pain. Ten percent (18/184) of the A-fibers had spontaneous discharge and 36% (17/47) of the C-fibers had spontaneous discharge. The incidence of spontaneous discharge in A-fibers and C-fibers was significantly greater (p < 0.01) than that seen in the control rats, but not significantly different from that seen in the paclitaxel-treated rats. Responses to noxious squeezing of a fold of skin were found in 79% of the spontaneously active A-fibers and 73% of the C-fibers, the remaining fibers responded to brushing the skin.

The CV distribution for all the fibers recorded in vincristine-treated rats is shown in Fig. 1. The distributions of A-fiber CVs were comparable to those seen in the control animals and in the paclitaxel-treated animals. However, the C-fiber CVs were significantly slower (0.79 ± 0.3 m/s; p < 0.01) than in the control and paclitaxel groups. This effect of vincristine has been noted previously (Tanner et al., 1998b); its significance is unknown.

As we saw in paclitaxel-treated rats, in vincristine-treated rats A-fibers with spontaneous discharge had CVs that were generally among the slowest of the A-fibers. The mean CV value for the spontaneously active A-fibers fibers (8.6 ± 6.9 m/s) was significantly slower (p < 0.01) than the mean of the A-fibers that did not have spontaneous discharge (17.1 ± 10.5 m/s). There was no significant difference between the mean CVs of the C-fibers that had spontaneous discharge and those that did not.

The frequency and pattern of spontaneous activity in the A-fibers and C-fibers recorded in vincristine-treated rats were very similar to those seen in the paclitaxel-treated rats. A-fiber spontaneous discharge had a mean frequency of 1.5 ± 2.9 Hz (range: 0.1–10 Hz) and the pattern of the discharge was either continuous (16/18) with irregular ISIs or bursting (2/18) with irregular intra-burst ISIs. The C-fiber spontaneous discharge had a mean frequency of 1.0 ± 0.7 Hz (range: 0.2–2.1 Hz) and for all the C-fibers (17/17) the pattern of the discharge was continuous with irregular ISIs. Specimen records are shown in Fig. 2.

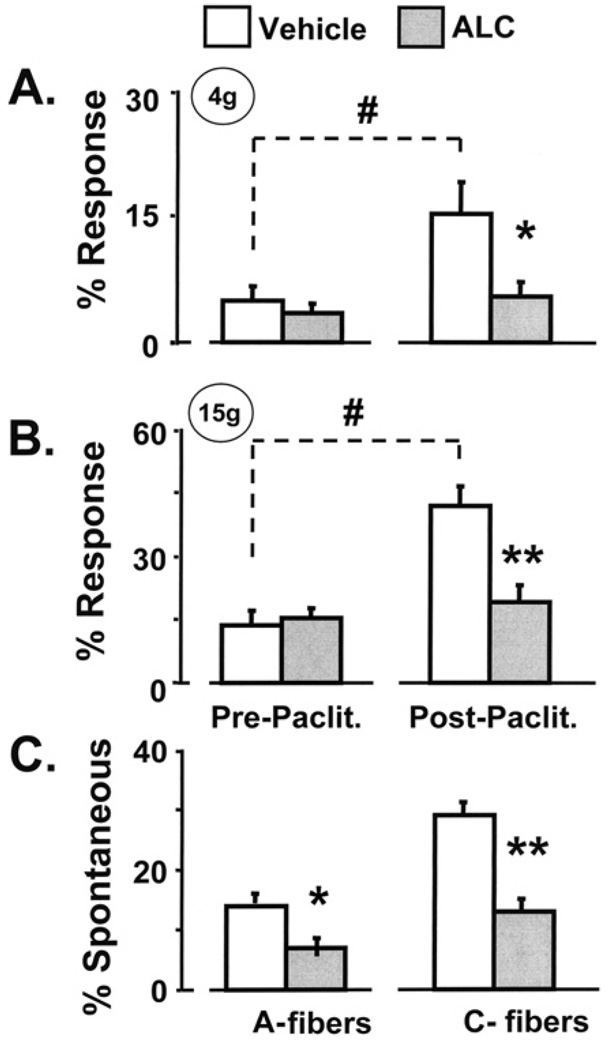

3.4. Effects of ALC treatment in the paclitaxel model

Paclitaxel-treated animals that received injections of vehicle developed the expected mechano-allodynia and mechano-hyperalgesia when tested on days 25–27 (Fig. 3). However, paclitaxel-treated animals that received ALC injections had no change in their sensitivity to mechanical stimulation (Fig. 3). This complete inhibition of paclitaxel-evoked mechano-allodynia and mechano-hyperalgesia replicates our previous ALC study (Flatters et al., 2006).

Fig. 3.

Behavioral and electrophysiological results of ALC treatment. The expected mechano-allodynia (A) and mechano-hyperalgesia (B) developed in paclitaxel-treated rats that received vehicle injections, but not in paclitaxel-treated rats that received ALC injections. Results from post-paclitaxel tests on days 25–27 are averaged. (C) ALC treatment significantly decreased the percentage of A-fibers and C-fibers that had spontaneous discharge. #p < 0.01 vs. pre-paclitaxel (baseline) response rate; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. vehicle-injected group.

We recorded 248 A-fibers and 102 C-fibers from 51 microfilaments in paclitaxel-treated rats that received control injections, and 242 A-fibers and 96 C-fibers from 48 microfilaments in paclitaxel-treated rats that received ALC. The A-fiber and C-fiber CV distributions were similar in the two groups, and comparable to those noted above (data not shown).

The incidence of spontaneous discharge in A-fibers (14%) and C-fibers (29%) in the paclitaxel-treated animals that received injections of vehicle (Fig. 3) was similar to that described previously for animals receiving paclitaxel alone. The A-fiber and C-fiber spontaneous discharge frequencies (1.5 ± 1.4 and 1.5 ± 0.5 Hz, respectively) and discharge patterns were also comparable (A-fibers: 94% continuous irregular discharge, 6% bursting discharge with irregular intra-burst ISIs; C-fibers: 99% continuous irregular discharge, and 1% continuous discharge with regular ISIs).

The incidence of spontaneous discharge in A-fibers and C-fibers in the paclitaxel-treated animals that received ALC injections (Fig. 3) was significantly decreased by approximately 50% (A-fibers: 7% vs. 14% in the control group; p < 0.05; C-fibers: 13% vs. 29% in the control group; p < 0.01). For those fibers that still had spontaneous discharge after ALC treatment, there were no changes (relative to the vehicle-injected group) in spontaneous discharge frequency, pattern of discharge (A-fibers: 1.0 ± 1.0 Hz; 95% continuous irregular discharge, 5% bursting discharge with irregular intraburst ISIs; C-fibers: 1.3 ± 0.7 Hz; 100% continuous irregular discharge), or the incidence of responses to brushing and squeezing the skin. Thus, ALC treatment reduced the incidence of spontaneously discharging A-fibers and C-fibers, but had no effect on any other discharge characteristic.

4. Discussion

This is the first description of a high incidence of abnormal spontaneous discharge in A-fiber and C-fibers in animals with confirmed paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked neuropathic pain.

The spontaneous discharge seen in vincristine- and paclitaxel-treated animals is unequivocally abnormal. In the control animals, none of the C-fibers and only 1% of the A-fibers had spontaneous discharge. The recording method involves cutting the nerve in preparation for microfilament dissections and it is well known that axons discharge when transected. However, this “injury discharge” lasts for no more than a minute or two in the vast majority of fibers (Wall et al., 1974; Devor and Bernstein, 1982; Michaelis et al., 1995; Blenk et al., 1996). The nearly complete absence of spontaneous discharge in the control animals is consistent with our procedures. Warming the hind paw will prevent discharge in cooling-specific afferents, and while this might activate some warm-specific afferents (C-fibers), the numbers of such fibers in the nerve are likely to be very small.

In prior work in paclitaxel-treated rats, Dina et al. (2001) briefly noted C-fibers with abnormal spontaneous discharge, but with a discharge frequency (≤0.03 Hz) that was much slower than what we observed. Previous experiments in vincristine-treated rats did not report a significant change in the incidence of spontaneously active fibers (Tanner et al., 1998b; Tanner et al., 2003). The explanation for these discrepancies is unknown. However, we note that the prior studies concentrated on the stimulus-evoked responses of C-fibers and were not designed to survey the incidence of spontaneous discharge.

4.1. Identity of spontaneously active fibers

Our counts of spontaneously discharging fibers include only those that responded to touching or squeezing the glabrous skin. We excluded fibers that did not respond to touching or squeezing in order to eliminate innocuous thermoreceptive afferents (warming- and cooling-specific afferents), which may have an ongoing discharge in response to ambient temperature that might be confused with abnormal spontaneous discharge. The number of fibers omitted because of this criterion was small and did not vary between groups. Our method might have excluded fibers with chemotherapy-evoked spontaneous discharge whose receptive fields were in hairy skin or deep tissues or in fibers whose sensory terminal arbors had degenerated. If so, then our counts are underestimates of the incidence of fibers with abnormal spontaneous discharge.

It is likely that the population of spontaneously active A-fibers that we found in paclitaxel-treated and vincristine-treated rats included both nociceptors and Aβ-fiber low-threshold mechanoreceptors (Aβ-LTMs). It is unlikely that the population included A-fibers innervating hairs because we included only fibers that responded to stimulation of the glabrous skin. It is not possible to unequivocally differentiate A-fiber nociceptors and Aβ-LTMs on the basis of conduction velocity alone because many A-fiber nociceptors have CVs in the Aβ range (Djouhri and Lawson, 2004). However, the mean CV for the A-fiber nociceptors is significantly slower than that of the Aβ-LTMs, such that combining their CV distributions yields a clearly bimodal distribution with peaks (medians), in the rat, of approximately 8 m/s for the nociceptors and 17 m/s for the Aβ-LTMs (Djouhri and Lawson, 2004). Our A-fiber samples from naïve, vehicle-injected, paclitaxel-treated, and vincristine-treated rats also had bimodal CV distributions (Fig. 1). In both paclitaxel- and vincristine-treated rats, most of the spontaneously active A-fibers had CVs clustered around the slower peak, suggesting that most were nociceptors. In both paclitaxel- and vincristine-treated rats, the majority of spontaneously active A-fibers responded to noxious squeezing of a fold of skin, also suggesting that these fibers were nociceptors. The spontaneously active A-fibers that responded to brushing the skin may have been low-threshold mechanoreceptors or sensitized nociceptors.

The population of spontaneously active C-fibers that we found in paclitaxel-treated and vincristine-treated rats is also likely to contain mostly nociceptors. The majority of the spontaneously active C-fibers responded to squeezing a fold of skin. We can rule out the possibility that the sample included C-fiber warming-specific afferents because these do not respond to touch or squeezing. It is possible that some of the spontaneously active C-fibers were low-threshold mechanoreceptors (Leem et al., 1993).

4.2. Origin of abnormal spontaneous discharge

It is probable that the chemotherapy-evoked A-fiber and C-fiber discharge originated within or near the fibers’ sensory terminal arbors. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of an origin in the length of axon that lies between the sensory terminals and the recording site. We have not determined whether chemotherapy-evoked neuropathy evokes spontaneous discharge from the sensory neuron’s cell body in the dorsal root ganglion.

4.3. Cause of chemotherapy-evoked spontaneous discharge

The spontaneous discharge in paclitaxel- and vincristine-treated rats described here may have had an ectopic origin. Axonal degeneration at the mid-axon level is not found in rats with vincristine- and paclitaxel-evoked pain (Tanner et al., 1998a; Topp et al., 2000; Flatters and Bennett, 2006), but these animals do have a loss of intraepidermal sensory terminal arbors (Siau et al., 2006). Thus, the spontaneous discharge reported here may be ectopic, arising from intact axons whose sensory terminal arbors had partly or completely degenerated. It is noteworthy that the ectopic discharge seen after axotomy at the peripheral nerve level usually has a very regular firing pattern which has been ascribed to spontaneous sinusoidal membrane potential oscillations (reviewed in Amir et al., 2005). However, all but one of the spontaneously discharging A-fibers and C-fibers that we found in paclitaxel-treated and vincristine-treated rats had distinctly irregular firing patterns.

A second possibility is that the spontaneous discharge may have come from intact fibers adjacent to fibers undergoing terminal arbor degeneration. Wu et al. (2002) described spontaneous discharge in intact C-fibers that travel in a nerve containing degenerated myelinated axons in the rat, and Ali et al. (1999) found the same after partial denervation of the skin in the monkey. This discharge has a distinctly low frequency (approximately one impulse per minute: 0.02 Hz), but nearly all of the spontaneously active fibers in our study had discharge frequencies that were 10–50X faster.

A third possibility is that the spontaneous discharge described here originates in intact primary afferent fibers that are sensitized due to a chemotherapy-evoked inflammation-like condition. Dougherty et al. (2004) noted that at least some patients with chronic paclitaxel-evoked pain have redness and swelling in the painful region, but we have not observed these effects in paclitaxel- or vincristine-treated rats. Levine and his colleagues have described a sensitization-like phenomenon in a subset of C-nociceptors in rats with neuropathic pain due to vincristine and paclitaxel (Tanner et al., 1998b, 2003; Dina et al., 2001). Molecules that are known to be involved in primary afferent sensitization, e.g., transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), protein kinase A, and protein kinase C, have also been shown to be involved in paclitaxel-evoked pain (Dina et al., 2001; Alessandri-Haber et al., 2004). We have shown that sensory terminal arbor degeneration in paclitaxel- and vincristine-treated rats is associated with activation of cutaneous Langerhans cells, the skin’s resident immuno-surveillance cells which are known to release pro-inflammatory mediators (reviewed in Siau et al., 2006). If the spontaneous discharge is due to chemotherapy-evoked inflammation, then non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) might be expected to reduce chemotherapy-evoked pain. However, NSAIDs have little or no effect on established vincristine-evoked pain, although there is evidence suggesting a prophylactic effect when they are co-administered with vincristine (Cata et al., 2004; Lynch et al., 2004). Of course, inflammatory mediators that do not derive from the cyclooxygenase cascade may have a role.

4.4. Consequences of spontaneous afferent discharge

Spontaneous discharge in A-fibers and C-fibers is likely to evoke spontaneous sensations; these will be pain sensations if the fibers are nociceptors and dysesthetic sensations if the fibers are low-threshold mechanoreceptors (Bennett, 1984). Spontaneous discharge in A-fiber and C-fiber nociceptors will engage central mechanisms that create and amplify neuropathic pain abnormalities (Woolf and Thompson, 1991; Ma and Woolf, 1996; Weng et al., 2003, 2005; Cata et al., 2006a).

4.5. Effects of ALC treatment in the taxol model

This is the first demonstration that ALC treatment inhibits abnormal spontaneous discharge in primary afferent neurons in paclitaxel-treated rats. This suggests that suppression of nociceptor spontaneous discharge may be the mechanism responsible for ALC’s inhibition of paclitaxel-evoked pain in behavioral assays (Ghirardi et al., 2005a,b; Flatters et al., 2006) and, conversely, it suggests that the pain is at least partly due to the spontaneous discharge. ALC’s action on mitochondrial function is a likely mechanism for its suppression of abnormal spontaneous discharge, although other mechanisms cannot be excluded (Virmani et al., 2005; Zanelli et al., 2005).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01-NS36834) and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. G.J.B. is a Canada Senior Research Chair. We thank Dr. Haiwei Jin and Ms. Lina Naso for their assistance.

References

- Alessandri-Haber N, Dina OA, Yeh JJ, Parada CA, Reichling DB, Levine JD. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 is essential in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain in the rat. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4444–4452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0242-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z, Ringkamp M, Hartke TV, Chien HF, Flavahan NA, Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Uninjured C-fiber nociceptors develop spontaneous activity and alpha-adrenergic sensitivity following L6 spinal nerve ligation in monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:455–466. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R, Kocsis JD, Devor M. Multiple interacting sites of ectopic spike electrogenesis in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2576–2585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4118-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ. Neuropathic pain. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of Pain. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. pp. 201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Blenk KH, Janig W, Michaelis M, Vogel C. Prolonged injury discharge in unmyelinated nerve fibres following transection of the sural nerve in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1996;215:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12994-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchiel KJ, Russell LC, Lee RP, Sima AA. Spontaneous activity of primary afferent neurons in diabetic BB/Wistar rats. A possible mechanism of chronic diabetic neuropathic pain. Diabetes. 1985;34:1210–1213. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.11.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Chen JH, Dougherty PM. Altered discharges of spinal wide dynamic range neurons and down-regulation of glutamate transporter expression in rats with paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 2006a;138:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and thalidomide ameliorate vincristine-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Lee BN, Reuben JM, Dougherty PM. Clinical and experimental findings in humans and animals with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Minerva Anesthesiol. 2006b;72:151–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DT, Honick AS, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial trafficking to synapses in cultured primary cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7035–7045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1012-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, Bernstein JJ. Abnormal impulse generation in neuromas: electrophysiology and ultrastructure. In: Culp WJ, Ochoa J, editors. Abnormal nerves and muscles as impulse generators. New York: Oxford University Press; 1982. pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, Seltzer Z. Pathophysiology of damaged nerves in relation to chronic pain. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. London: Churchill-Livingstone; 1999. pp. 129–164. [Google Scholar]

- Dina OA, Chen X, Reichling D, Levine JD. Role of protein kinase Cepsilon and protein kinase A in a model of paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat. Neuroscience. 2001;108:507–515. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouhri L, Koutsikou S, Fang X, McMullan S, Lawson SN. Spontaneous pain, both neuropathic and inflammatory, is related to frequency of spontaneous firing in intact C-fiber nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1281–1292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3388-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouhri L, Lawson SN. Abeta-fiber nociceptive primary afferent neurons: a review of incidence and properties in relation to other afferent A-fiber neurons in mammals. Brain Res Rev. 2004;46:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty PM, Cata JP, Cordella JV, Burton A, Weng HR. Taxol-induced sensory disturbance is characterized by preferential impairment of myelinated fiber function in cancer patients. Pain. 2004;109:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatters SJL, Bennett GJ. Ethosuximide reverses paclitaxel- and vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2004;109:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatters SJL, Bennett GJ. Studies of peripheral sensory nerves in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: Evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Pain. 2006;122:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatters SJL, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Acetyl-l-carnitine prevents and reduces paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy. Neurosci Lett. 2006;397:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi O, Lo Giudice P, Pisano C, Vertechy M, Bellucci A, Vesci L, Cundari S, Miloso M, Rigamonti LM, Nicolini G, Zanna C, Carminati P. Acetyl-l-Carnitine prevents and reverts experimental chronic neurotoxicity induced by oxaliplatin, without altering its antitumor properties. Anticancer Res. 2005a;25:2681–2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi O, Vertechy M, Vesci L, Canta A, Nicolini G, Galbiati S, Ciogli C, Quattrini G, Pisano C, Cundari S, Rigamonti LM. Chemotherapy-induced allodynia: neuroprotective effect of acetyl-l-carnitine. In Vivo. 2005b;19:631–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracely RH, Lynch S, Bennett GJ. Painful neuropathy: altered central processing, maintained dynamically by peripheral input. Pain. 1992;51:175–194. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90259-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govrin-Lippmann R, Devor M. Ongoing activity in severed nerves: source and variation with time. Brain Res. 1978;159:406–410. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppelmann B, Gallar J, Trost B, Schmidt RF, Belmonte C. Three-dimensional reconstruction of scleral cold thermoreceptors of the cat eye. J Comp Neurol. 2001;441:148–154. doi: 10.1002/cne.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppelmann B, Messlinger K, Neiss WF, Schmidt RF. Mitochondria in fine afferent nerve fibres of the knee joint in the cat: a quantitative electron-microscopical examination. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;275:493–501. doi: 10.1007/BF00318818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander KC, Bennett GJ. The onset of a painful peripheral neuropathy in rat: a partial and differential deafferentation and spontaneous discharge in A-delta and A-beta primary afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:734–744. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander KC, Wakisaka S, Bennett GJ. Spontaneous discharge originates in the dorsal root ganglion at the onset of a painful peripheral neuropathy in rat. Neurosci Lett. 1992;138:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90920-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem JW, Willis WD, Chung JM. Cutaneous sensory receptors in the rat foot. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1684–1699. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JJ, 3rd, Wade CL, Zhong CM, Mikusa JP, Honore P. Attenuation of mechanical allodynia by clinically utilized drugs in a rat chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain model. Pain. 2004;110:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QP, Woolf CJ. Progressive tactile hypersensitivity: an inflammation-induced incremental increase in the excitability of the spinal cord. Pain. 1996;67:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA, Ringkamp M, Campbell JN, Raja SN. Peripheral mechanism of cutaneous nociception. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editors. Melzack and Wall’s textbook of pain. London: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M, Blenk KH, Jänig W, Vogel C. Development of spontaneous activity and mechanosensitivity in axotomized afferent nerve fibers during the first hours after nerve transection in rats. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1020–1027. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polomano RC, Mannes AJ, Clark US, Bennett GJ. A painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat produced by the chemotherapeutic drug, paclitaxel. Pain. 2001;94:293–304. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siau C, Bennett GJ. Dysregulation of neuronal calcium homeostasis in chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1485–1490. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000204318.35194.ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siau C, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies: loss of epidermal innervation and activation of Langerhans cells. Exptl Neurol. 2006;201:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner KD, Levine JD, Topp KS. Microtubule disorientation and axonal swelling in unmyelinated sensory axons during vincristine-induced painful neuropathy in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1998a;395:481–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner KD, Reichling DB, Levine JD. Nociceptor hyper-responsiveness during vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:6480–6491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06480.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner KD, Reichling DB, Gear RW, Paul SM, Levine JD. Altered temporal pattern of evoked afferent activity in a rat model of vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2003;118:809–817. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp KS, Tanner KD, Levine JD. Damage to the cytoskeleton of large diameter sensory neurons and myelinated axons in vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:563–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhm JH, Yung WK. Neurologic complications of cancer therapy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 1999;1:428–437. doi: 10.1007/s11940-996-0006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstappen CC, Heimans JJ, Hoekman K, Postma TJ. Neurotoxic complications of chemotherapy in patients with cancer: clinical signs and optimal management. Drugs. 2003;63:1549–1563. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani A, Gaetani F, Binienda Z. Effects of metabolic modifiers such as carnitines, coenzyme Q10, and PUFAs against different forms of neurotoxic insults: metabolic inhibitors, MPTP, and methamphetamine. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;21053:183–191. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PD, Waxman S, Basbaum AI. Ongoing activity in peripheral nerve: injury discharge. Exptl Neurol. 1974;45:576–589. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(74)90163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Aravindan N, Cata JP, Chen JH, Shaw AD, Dougherty PM. Spinal glial glutamate transporters downregulate in rats with taxol-induced hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Cordella JV, Dougherty PM. Changes in sensory processing in the spinal dorsal horn accompany vincristine-induced hyperalgesia and allodynia. Pain. 2003;103:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Thompson SW. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991;44:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90100-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Ringkamp M, Murinson BB, Pogatzki EM, Hartke TV, Weerahandi HM, Campbell JN, Griffin JW, Meyer RA. Degeneration of myelinated efferent fibers induces spontaneous activity in uninjured C-fiber afferents. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7746–7753. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07746.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W, Boroujerdi A, Bennett GJ, Luo ZD. Chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy: analgesic effects of gabapentin and effects on expression of the alpha-2-delta type-1 calcium channel subunit. Neuroscience. 2007;144:714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanelli SA, Solenski NJ, Rosenthal RE, Fiskum G. Mechanisms of ischemic neuroprotection by acetyl-l-carnitine. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1053:153–161. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]