Abstract

Background High-level adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is associated with favourable patient outcomes. In resource-constrained settings, however, there are few validated measures. We examined the correlation between clinical outcomes and the medication possession ratio (MPR), a pharmacy-based measure of adherence.

Methods We analysed data from a large programmatic cohort across 18 primary care centres providing ART in Lusaka, Zambia. Patients were stratified into three categories based on MPR-calculated adherence over the first 12 months: optimal (≥95%), suboptimal (80–94%) and poor (<80%).

Results Overall, 27 115 treatment-naïve adults initiated and continued ART for ≥12 months: 17 060 (62.9%) demonstrated optimal adherence, 7682 (28.3%) had suboptimal adherence and 2373 (8.8%) had poor adherence. When compared with those with optimal adherence, post-12-month mortality risk was similar among patients with sub-optimal adherence [adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) = 1.0; 95% CI: 0.9–1.2] but higher in patients with poor adherence (AHR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.4–2.2). Those <80% MPR also appeared to have an attenuated CD4 response at 18 months (185 cells/µl vs 217 cells/µl; P < 0.001), 24 months (213 cells/µl vs 246 cells/µl; P < 0.001), 30 months (226 cells/µl vs 261 cells/µl; P < 0.001) and 36 months (245 cells/µl vs 275 cells/µl; P < 0.01) when compared with those above this threshold.

Conclusions MPR was predictive of clinical outcomes and immunologic response in this large public sector antiretroviral treatment program. This marker may have a role in guiding programmatic monitoring and clinical care in resource-constrained settings.

Keywords: HIV, adherence, medication possession ratio, mortality, survival, antiretroviral therapy, Africa, Zambia

Introduction

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is essential for maximal suppression of viral replication and avoidance of drug resistance.1–5 As such, good adherence is believed to be a critical determinant of long-term survival among HIV-infected individuals.6–9 Where availability of second-line or salvage antiretroviral drug regimens is limited, it is especially important to leverage maximum durability for first-line regimens.6

Early studies in Africa reported adherence levels as high or higher than those observed in developed countries.10,11 However, measures used to assess adherence vary11 and many have not been validated in the context of rapid ART scale-up.12 In this analysis, we describe the impact of ART adherence on immunologic response and survival in a large population of adults initiating ART in Lusaka, Zambia. We use the medication possession ratio—a simple metric that has been correlated with virologic outcomes in developed countries13–15—to describe the adherence behaviour of our population.

Methods

In Lusaka, Zambia, a large-scale public sector HIV care and treatment program was established by the Zambian Ministry of Health in April 2004. Clinical care, patient tracking and outcomes monitoring for the Lusaka program have been described elsewhere.16,17 Briefly, care has been standardized across all sites according to the Zambian national guidelines for adult HIV treatment. In the first months of the program, ART was initiated in individuals with either a CD4+ cell count <200 cells/μl or WHO stage III/IV. Since 2005, the Zambian guidelines have been revised, so that ART eligibility for patients in WHO Stage 3 requires a CD4+ cell count ≤350 cells/μl. First-line drug regimens in Zambia had comprised two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (lamivudine with either zidovudine or stavudine) and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI; nevirapine or efavirenz). Since July 2007, however, the Zambian Ministry of Health has incorporated combination tenofovir/emtricitabine as a first-line nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor backbone for individuals newly initiating therapy; those continuing therapy remain on their previous regimen except in cases of toxicity or treatment failure.18 Antiretroviral drugs provided are free of charge and dispensed by pharmacy technicians or nurses within the ART clinic itself. Patients are encouraged to enlist a ‘buddy’ for adherence support, usually a friend or family member. These individuals are authorized to collect a limited number of drug refills when the patient is unable to attend a pharmacy appointment. Medical information, including the number of pills dispensed and the date of next visit, is entered into an electronic patient tracking system.19 Patients on ART who are >10 days late for a scheduled appointment are followed up by community health workers at their homes.20

We calculated adherence based on a variation of the commonly-reported medication possession ratio (MPR).21,22 We divided the number of days late for pharmacy refills by total days on therapy, and then subtracted that percentage from 100%. The resulting figure represents the percentage of days a patient is known to have medication on hand and has been correlated with HIV virologic outcomes in Africa.23 In the Lusaka public sector, patients are provided a buffer stock of 3 days with each drug dispensation; therefore, we began calculating lateness on the fourth day after a missed pharmacy appointment.24 Since ART is provided free charge by the Zambian government, the ‘black market’ for antiretroviral drugs is believed to be minimal to non-existent.

Patients were categorized as optimally adherent (≥95%), suboptimally adherent (80–94%) and poorly adherent (<80%). Owing to the high rates of early mortality in our setting and others like it,16,25 we excluded patients from this analysis who had been on therapy for <12 months. We reasoned that poor patient outcomes associated with adherence would likely manifest later in the course of treatment, after viral drug resistance and treatment failure had developed. Early death also introduces bias into the MPR measurement, since these patients do not have the same opportunity to fully demonstrate long-term adherence behaviours. For these reasons, we considered only adherence behaviour during the first 12 months and evaluated outcomes after 12 months.

Patients are categorized as ‘active’ if they attended their last scheduled clinical and/or pharmacy visit within 30 days of their appointment date. ‘Dead’ patients are so classified in the medical record after confirmation from family members, friends or community health workers. ‘Inactive’ patients have formally withdrawn from the HIV treatment program. ‘Late’ patients are >30 days overdue for their last scheduled clinical and/or pharmacy visit and cannot be located via community health worker contact tracing. In survival analyses and rate calculations, inactive patients are censored as of the date they became inactive, and late patients are censored 30 days after their last scheduled visit.

We analysed programmatic data from treatment-naïve adults (>15 years) initiating ART across 18 primary care sites in Lusaka, Zambia from April 1, 2004 to September 30, 2007. To be included in the analysis, individuals had to be active for 12 months of follow-up, so that the MPR measure for adherence could be calculated. Those who had died, withdrew from the program or were lost to follow-up prior to 12 months were excluded. To compare demographic and clinical characteristics among members of the study population and those who were excluded, we analysed categorical variables using Pearson's Chi-square test. Non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare continuous variables. We calculated mortality rates using individual follow-up time from 12 months onward. We used logistic regression to describe the association between these characteristics and adherence to therapy at 12 months. In this multivariable analysis, we included all covariates associated with adherence at a P-value < 0.10 level.

Log-rank tests were used to evaluate differences in survival among adherence categories using Kaplan–Meier analysis; Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the risk of death. The proportional hazards assumption was confirmed via the Kolmogorov-type supremum test (P = 0.83).26 All factors associated in crude analysis with P-value < 0.10, or that have been previously shown to be associated with mortality in our setting,16 were included in the multivariable analysis. However, we excluded any such covariate if it was believed to be an intermediary step between the exposure and outcome. (For example, we include enrollment CD4+ lymphocyte count in the multivariable models but not later measures of CD4+). In all adjusted models, continuous covariates were categorized based on the conventions in the medical literature. Finally, we compared clinical and immunologic outcomes (i.e. CD4+ count, weight, haemoglobin) longitudinally according to MPR categories. Means and corresponding 95% CIs at each time point were calculated; trends were evaluated at each 6-month interval using separate Student's t-tests.

Available patient data through November 1, 2008, the dataset freeze date, were considered in this report. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Zambia (Lusaka, Zambia) and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, AL, USA), and by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA).

Results

Cohort description

From April 1, 2004 to September 30, 2007, 37 039 ART-naïve adults (>15 years of age) initiated treatment across 18 sites in Lusaka, Zambia. Of these, 27 115 (73.2%) remained active in the program at or after 12 months and were thus included in the analysis. A total of 9924 (26.8%) were excluded from the analysis because they had left the program before reaching the 12 month threshold: 1133 withdrew from the program, 5114 were late for patient visits and 3677 had died (crude mortality rate = 105.5/100 person-years, 95% CI: 102.1–108.9). A comparison of those included and excluded from the analysis is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of treatment-naïve adults initiating ART in Lusaka, Zambia, from April 1, 2004 to September 30, 2007 and continuing ART for >12 months

| Included in analysis |

Excluded from analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Value | N | Value | P | |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 27 115 | 35 (30–41) | 9924 | 34 (29–40) | <0.001 |

| 15–25 | 2718 | 10.0% | 1285 | 12.9% | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 12 159 | 44.8% | 4526 | 45.6% | |

| 36–45 | 8636 | 31.8% | 2884 | 29.1% | |

| 46–55 | 2875 | 10.6% | 901 | 9.1% | |

| ≥56 | 727 | 2.7% | 328 | 3.3% | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 16 889 | 62.3% | 5566 | 56.1% | <0.001 |

| Male | 10 226 | 37.7% | 4358 | 43.9% | |

| Adherence supporter | |||||

| No | 5469 | 20.2% | 3289 | 33.1% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 21 646 | 79.8% | 6635 | 66.9% | |

| CD4+ lymphocyte count, median cells/μl (IQR) | 26 068 | 132 (69–198) | 9409 | 110 (48–191) | <0.001 |

| ≥200 cells/μl | 6358 | 24.4% | 2121 | 22.5% | <0.001 |

| 50–199 cells/μl | 15 274 | 58.6% | 4855 | 51.6% | |

| <50 cells/μl | 4436 | 17.0% | 2433 | 25.9% | |

| WHO Stage | |||||

| I or II | 8741 | 32.5% | 2330 | 23.8% | <0.001 |

| III | 15 789 | 58.6% | 6057 | 61.8% | |

| IV | 2398 | 8.9% | 1420 | 14.5% | |

| Haemoglobin, median g/dl (IQR) | 23 796 | 10.9 (9.6–12.3) | 8370 | 10.2 (8.7–11.8) | <0.001 |

| ≥8.0 g/dl | 21 995 | 92.4% | 7122 | 85.1% | <0.001 |

| <8.0 g/dl | 1801 | 7.6% | 1248 | 14.9% | |

| BMI, median kg/m2 (IQR) | 24 250 | 20.0 (18.1–22.3) | 8358 | 18.9 (16.9–21.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥20 kg/m2 | 12 147 | 50.1% | 3078 | 36.8% | <0.001 |

| 18–19 kg/m2 | 6148 | 25.4% | 2015 | 24.1% | |

| 16–17 kg/m2 | 4258 | 17.6% | 1930 | 23.1% | |

| <16 kg/m2 | 1697 | 7.0% | 1335 | 16.0% | |

| Tuberculosis co-infection at enrollment | |||||

| No | 23 488 | 86.6% | 8569 | 86.3% | 0.49 |

| Yes | 3627 | 13.4% | 1355 | 13.7% | |

| Initial ART regimen | |||||

| d4T + 3TC + NVP | 10 699 | 39.7% | 4691 | 48.0% | <0.001 |

| ZDV + 3TC + NVP | 12 996 | 48.3% | 3501 | 35.8% | |

| d4T + 3TC + EFV | 1523 | 5.7% | 875 | 8.9% | |

| ZDV + 3TC + EFV | 1026 | 3.8% | 423 | 4.3% | |

| TDF + FTC + NVP | 229 | 0.9% | 98 | 1.0% | |

| TDF + FTC + EFV | 448 | 1.7% | 194 | 2.0% | |

| Adherence by MPR, median (IQR)a | 27 115 | 97.9 (91.2–100.0) | 9924 | 100.0 (92.6–100.0) | <0.00l |

| 95–100% | 17 060 | 62.9% | 7051 | 71.0% | <0.00l |

| 80–94% | 7682 | 28.3% | 1412 | 14.2% | |

| < 80% | 2373 | 8.8% | 1461 | 14.7% | |

aFor those included in the analysis, adherence by MPR was based on behaviour within the first 12 months from ART initation. For those excluded because they were not active at 12 months, MPR was based on time from ART initiation to censor date. ART = antiretrovinal therapy; D4T = stavudine; ZDV = zidovudine; 3TC = lamivudine; NVP = nevirapine; EFV = efavirenz.

Of the 27 115 included in this analysis, 1419 (5.2%) withdrew from the program, 3067 (11.3%) were late for their most recent scheduled visit, and 823 (3.0%) were known to have died (crude post-12 month mortality rate = 2.1/100 person-years, 95% CI: 2.0, 2.3) after the initial 12-month period. The median observation period was 15.7 [interquartile range (IQR) = 7.5–26.4] months, from 12 months onward.

Of 27 115 patients, 17 060 (62.9%) demonstrated optimal adherence, 7682 (28.3%) had suboptimal adherence and 2373 (8.8%) had poor adherence over the first 12 months on therapy (Figure 1). Individuals with an MPR <80% were more likely to have a higher median CD4 count at enrollment than those with optimal adherence. When compared with those with optimal adherence, individuals in the 80–94 and <80% MPR were generally younger and were less likely to report adherence support (i.e. adherence ‘buddy’) over the first 3 months following ART initiation. The proportion of individuals with tuberculosis at time of ART initiation was lower among individuals with suboptimal adherence (12.2 vs 14.0%; P < 0.001) when compared with those with optimal adherence. The proportion of patients who withdrew from the program or were lost to follow-up after 12 months increased as adherence declined categorically (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of adherence to ART over the first 12 months on treatment among adults surviving to at least 12 months in Lusaka, Zambia, between April 1, 2004 and September 30, 2007. Adherence was measured by the number of days a patient had antiretroviral drugs available according to pharmacy refill data

Table 2.

Characteristics by adherencea category for treatment-naïve adults initiating ART in Lusaka, Zambia, from April 1, 2004 to September 30, 2007 and continuing ART for >12 months

| Optimal (95–100%) |

Sub-optimal (80–94%) |

Poor (<80%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Value | N | Value | Pb | N | Value | Pb | |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 17 060 | 35 (30–41) | 7682 | 34 (29–41) | 0.03 | 2373 | 33 (28–40) | <0.001 |

| 15–25 | 1601 | 9.4% | 782 | 10.2% | 0.12 | 335 | 14.1% | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 7620 | 44.7% | 3458 | 45.0% | 1081 | 45.6% | ||

| 36–45 | 5525 | 32.4% | 2441 | 31.8% | 670 | 28.2% | ||

| 46–55 | 1863 | 10.9% | 785 | 10.2% | 227 | 9.6% | ||

| ≥56 | 451 | 2.6% | 216 | 2.8% | 60 | 2.5% | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 10 730 | 62.9% | 4685 | 61.0% | <0.01 | 1474 | 62.1% | 0.46 |

| Male | 6330 | 37.1% | 2997 | 39.0% | 899 | 37.9% | ||

| Adherence supporter reported at enrollment | 14 057 | 82.4% | 5943 | 77.4% | <0.001 | 1646 | 69.4% | <0.001 |

| CD4+ lymphocyte count, median cells/µl (IQR) | 16 469 | 132 (70–196) | 7350 | 129 (68–198) | 0.59 | 2249 | 139 (73–207) | <0.001 |

| ≥200 cells/µl | 3943 | 23.9% | 1804 | 24.5% | 0.60 | 611 | 27.2% | <0.01 |

| 50–199 cells/µl | 9699 | 58.9% | 4293 | 58.4% | 1282 | 57.0% | ||

| <50 cells/µl | 2827 | 17.2% | 1253 | 17.0% | 356 | 15.8% | ||

| WHO Stage | ||||||||

| I or II | 5532 | 32.6% | 2436 | 32.0% | 0.19 | 773 | 32.9% | 0.81 |

| III | 9956 | 58.7% | 4467 | 58.7% | 1366 | 58.1% | ||

| IV | 1473 | 8.7% | 713 | 9.4% | 212 | 9.0% | ||

| Haemoglobin, median g/dl (IQR) | 15 186 | 10.9 (9.6–12.3) | 6657 | 10.9 (9.6–12.3) | 0.42 | 1953 | 11.0 (9.5–12.4) | 0.49 |

| ≥8.0 g/dl | 14 060 | 92.6% | 6154 | 92.4% | 0.71 | 1781 | 91.2% | 0.03 |

| <8.0 g/dl | 1126 | 7.4% | 503 | 7.6% | 172 | 8.8% | ||

| BMI, median kg/m2 (IQR) | 15 356 | 20.0 (18.1–22.3) | 6846 | 20.0 (18.0–22.2) | 0.34 | 2048 | 19.9 (18.0–22.3) | 0.53 |

| ≥20 kg/m2 | 7725 | 50.3% | 3418 | 49.9% | 0.42 | 1004 | 49.0% | 0.75 |

| 18–19 kg/m2 | 3909 | 25.5% | 1703 | 24.9% | 536 | 26.2% | ||

| 16–17 kg/m2 | 2653 | 17.3% | 1241 | 18.1% | 364 | 17.8% | ||

| <16 kg/m2 | 1069 | 7.0% | 484 | 7.1% | 144 | 7.0% | ||

| Tuberculosis co-infection at enrollment | 2382 | 14.0% | 937 | 12.2% | <0.001 | 308 | 13.0% | 0.19 |

| Initial ART regimen | ||||||||

| d4T + 3TC + NVP | 6731 | 39.7% | 3042 | 39.9% | 0.07 | 926 | 39.7% | 0.24 |

| ZDV + 3TC + NVP | 8222 | 48.5% | 3655 | 47.9% | 1119 | 47.9% | ||

| d4T + 3TC + EFV | 943 | 5.6% | 440 | 5.8% | 140 | 6.0% | ||

| ZDV + 3TC + EFV | 628 | 3.7% | 298 | 3.9% | 100 | 4.3% | ||

| TDF + FTC + NVP | 167 | 1.0% | 49 | 0.6% | 13 | 0.6% | ||

| TDF + FTC + EFV | 271 | 1.6% | 141 | 1.8% | 36 | 1.5% | ||

| Lost to follow-up or withdrawn after 12 months | 2294 | 13.4% | 1404 | 18.3% | <0.001 | 788 | 33.2% | <0.001 |

aDefined at 12 months of therapy as the percentage of time on therapy with ART via pharmacy claims.

bBased on comparisons to the optimal adherence category.

ART = antiretroviral therapy; D4T = stavudine; ZDV = zidovudine; 3TC = lamivudine; NVP = nevirapine; EFV = efavirenz.

Several medical characteristics appeared protective against poor adherence. Individuals who were >35 years [odds ratio (OR): 0.8; 95% CI: 0.7–0.9] or reported presence of an adherence ‘buddy’ (OR: 0.5; 95%CI: 0.5–0.6) were less likely to have MPR <80%. When compared with those with CD4 count >200 cells/µl, those with lower baseline CD4 counts were less likely to be poorly adherent over the first 12 months: 50–199 cells/µl (OR: 0.9, 95% CI = 0.8–1.0) and <50 cells/µl (OR: 0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.9). These trends remained consistent in multivariable analysis. Baseline World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage, haemoglobin, body mass index (BMI) and tuberculosis status were not predictive of poor adherence (data not shown).

Impact of adherence on patient survival

In Kaplan–Meier analysis, individuals with <80% adherence had a significantly higher risk of death when compared with those in other adherence categories (log rank P = 0.0001). Survival was similar among the remaining two groups (Figure 2). In unadjusted proportional hazards regression, the relative hazard for death was 1.7 (95% CI: 1.4–2.1) among those with poor adherence, when compared with those with optimal adherence. These findings remained virtually unchanged in a multivariable model controlling for sex, age, adherence support, baseline CD4+ lymphocyte count, baseline WHO Stage and initial regimen dispensed [n = 25 836; adjusted hazard ratio (AHR): 1.7; 95% CI: 1.4–2.2]. Baseline haemoglobin and BMI were not included in this initial multivariable model, since early versions of our patient tracking software did not routinely collect these data. In a separate model that included these two parameters (n = 20 951), the hazard for mortality associated with poor adherence did not change appreciably (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Post-12-month mortality by adherence category for ART-naïve adults initiating ART in Lusaka, Zambia, between April 1, 2004 and September 30, 2007. Adherence was measured by the number of days a patient had antiretroviral drugs available according to pharmacy refill data. The numbers shown at the bottom of the graph represent the number of patients active in each adherence category at 6-monthly intervals. Perfect survival in the first 12 months is a result of our study design. To be eligible for inclusion in this analysis, patients had to remain alive, active, and on ART until at least 12 months

Table 3.

Factors associated with post-12-month mortality among treatment-naïve adults initiating ART in Lusaka, Zambia, from April 1, 2004 to September 30, 2007 and continuing ART for >12 months

| Crude Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adherencea | ||

| Optimal (95–100%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Suboptimal (80–94%) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

| Poor (<80%) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 1.7 (1.4–2.3) |

| Age | ||

| ≤35 years | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| >35 years | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Male | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| Adherence supporter | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| CD4 count | ||

| ≥200 cells/μl | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–199 cells/μl | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) |

| <50 cells/μl | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) |

| WHO Stage | ||

| I or II | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| III | 1.6 (1.4–1.9) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

| IV | 2.5 (2.0–3.2) | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) |

| Haemoglobin | ||

| ≥8.0 g/dl | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| <8.0 g/dl | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) |

| BMI | ||

| ≥16 kg/m2 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| <16 kg/m2 | 2.2 (1.8–2.8) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) |

| Initial ART regimenb | ||

| D4T + 3TC + NVP | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ZDV + 3TC + NVP | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| D4T + 3TC + EFV | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) |

| ZDV + 3TC + EFV | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

aAdherence defined by MPR.

bIn adjusted models, tenofovir-based regimens were not included due to relatively small number of patients who received these drugs (n = 636) and deaths documented among this group (n = 2).

ART = antiretroviral therapy; D4T = stavudine; ZDV = zidovudine; 3TC = lamivudine; NVP = nevirapine; EFV = efavirenz.

Impact of adherence on clinical and immunologic outcomes

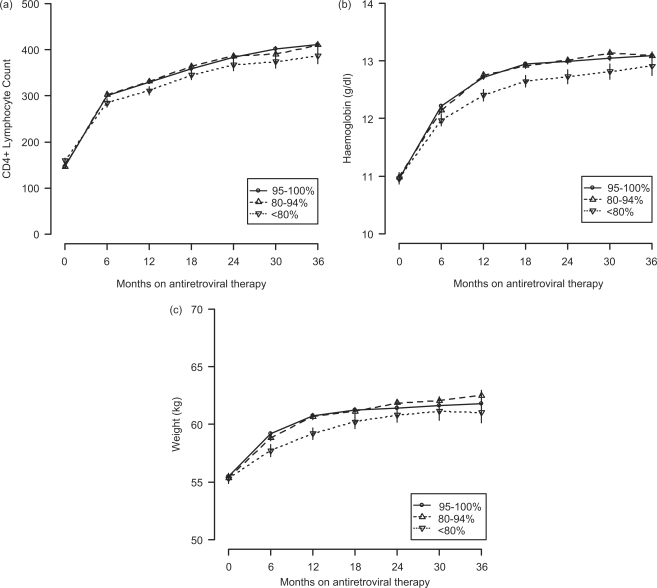

While trends in CD4+ response, haemoglobin response and weight gain appeared similar for individuals in the optimal and suboptimal adherence categories, outcomes generally appeared worse among those with poor adherence (Figure 3). When compared with individuals with ≥80% adherence, for example, those with poor adherence appeared to have an attenuated CD4 response at 18 months (185 vs 217 cells/µl; P < 0.001), 24 months (213 vs 246 cells/µl; P < 0.001), 30 months (226 vs 261 cells/µl; P < 0.001) and 36 months (245 vs 275 cells/µl; P < 0.01). Those with <80% MPR in their first 12 months also had attenuated increases in weight and haemoglobin at 18 months (5.0 vs 5.8 kg; P < 0.001 and 1.7 vs 2.0 g/dl; P < 0.001), 24 months (5.5 vs 6.0 kg; P < 0.05 and 1.7 vs 2.0 g/dl; P < 0.001), 30 months (5.8 vs 6.3 kg; P < 0.17 and 1.8 vs 2.1 g/dl; P < 0.01) and 36 months (5.6 vs 6.4 kg; P < 0.06 and 2.0 vs 2.1 g/dl; P = 0.35).

Figure 3.

Immunologic and clinical responses by adherence category for ART-naïve adults initiating ART in Lusaka, Zambia, between April 1, 2004 and September 30, 2007, and remaining on ART for >12 months. These include (a) CD4+ lymphocyte count, (b) haemoglobin and (c) weight

Discussion

We investigated ART adherence in an extremely busy, public sector ART program in sub-Saharan Africa. When optimal adherence was defined as MPR ≥ 95%, ∼60% met this criterion. Less than 10% met criteria for poor adherence (MPR < 80%); however, we observed poor clinical and immunologic response among individuals in this group. Although routine viral load data are not available in our setting, the 80% MPR threshold appears to hold some significance for crude measures of treatment response such as mortality and CD4+ lymphocyte count improvement.

MPR and MPR-like measurements for adherence (e.g. pharmacy refills, timeliness to clinical appointments) have been closely associated with virologic and clinical outcomes among patients on ART.8,9,11,23 We observed increased mortality after 12 months among those with adherence <80%: a finding similar to other studies in the published literature. For example, Hogg and colleagues found that intermittent use of ART (defined as drug refills of <75%) was associated with a nearly 3-fold risk in mortality in British Columbia.8 Nachega et al.9 found that adherence to antiretroviral drug refills of <80% was associated with a 3-fold increase for death in the South African private sector. The risk for adverse outcomes observed in this cohort was of a slightly lesser magnitude when compared with other published series. One reason may have been the eligibility criteria for inclusion in our analysis. To better understand the impact of adherence on later outcomes, we included only individuals enrolled in the program for >12 months. Thus, there is selection bias towards longer term survivors, regardless of drug adherence behaviour. This is most evident in the baseline characteristics of the population, where those in the lower adherence stratifications had somewhat higher median CD4+ lymphocyte counts. The attenuated effect may be a reflection of the higher baseline mortality risk in Zambia—regardless of immune status—compared with Canada or South Africa.

As in other studies,27 we observed an association between adherence and CD4+ lymphocyte response. Individuals with adherence of <80% had an attenuated response at 18, 24, 30 and 36 months when compared with those at or above this MPR threshold. Haemoglobin and weight (usually described through BMI) are other clinical measures shown to be independently predictive of mortality among patients initiating ART.16,28,29 We noted improved recovery within both parameters among those with adherence ≥80%. These results lend support to our findings on patient survival and MPR.

The post-12-month mortality rate observed in this cohort (2.1 deaths/100 patient-years) was slightly higher than what has been reported among HIV-uninfected individuals in Africa (∼0.6–0.8 deaths/100 patient-years), and well below that of HIV-infected individuals without access to treatment (∼11–13 deaths/100 patient-years).30–32 This finding speaks to the favourable long-term outcomes among patients on ART. However, we recognize that selection biases may contribute to these findings as well. Our analysis cohort comprised individuals who were likely healthier than the general population initiating ART, having survived beyond periods of highest mortality risk (i.e. first 90 days on ART) to at least 12 months.16 Another potential bias may have been caused by our ascertainment of patient vital status. Although systems are in place to follow up those with missed visits, nearly 10% were late for appointments or withdrew altogether in the post-12-month period, a scenario common to other sub-Saharan programs.33 If a significant proportion of follow-up losses were related to death—a distinct possibility given the local tradition of returning to the rural family home at times of severe illness—then this would lead to underestimated mortality.

For individual patient care, we recognize that the utility of our findings may be limited. We focused on a survival outcome due to constraints of our programmatic database, but the ability to predict virologic suppression may be more relevant for clinical decision making. Bisson and colleagues, for example, demonstrated that pharmacy refill-based adherence measures may perform better than CD4+ monitoring to predict virologic failure; overall performance of adherence, however, still led to significant misclassification of patient outcomes (i.e. missed virologic failure, unnecessary regimen change) across several different thresholds.34 We observed similar findings among patients with discordant clinical and immunologic treatment responses in Lusaka, suggesting that MPR measurements alone may be insufficient to predict virologic suppression.24 Instead, it should either be considered as a triaging tool or as part of more extensive algorithms in predicting virologic failure. In addition, while 95% adherence threshold is commonly referenced, recent studies have shown that even moderate levels (80–90%) of adherence can result in viral suppression when combination regimens are used.35,36 Establishment of adherence thresholds that reliably predict virologic treatment failure and viral drug resistance could greatly assist individual patient care in resource-constrained settings.

In contrast, our demonstrated association between MPR and mortality could provide an important framework for program monitoring in African settings. In Lusaka, for example, we currently utilize a programmatic database19 to generate facility-level reports for clinical care quality and performance.37 An aggregate MPR metric could be generated for a given facility and serve as a clinic-level performance indicator. Sites with a high proportion of patients with poor adherence (e.g. <80%) could be identified and evaluated for potential interventions incorporating patient reminders, community education or adherence support.23,38–40 This feedback loop between patient outcomes and service improvement is a critical link to maintaining a high standard of clinical care, particularly in settings where HIV services are expanding rapidly and task shifting is employed to relieve critical health personnel shortages.41 Aggregate data could also assist policy makers and program managers at the district, provincial and national level, as they tailor specific interventions to optimize treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the largest African cohort in the published literature evaluated for adherence, owing to the unprecedented resources made available through the Zambian government, the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. We believe the pharmacy data to be complete because of the free antiretroviral drugs provided by the Zambian Ministry of Health (thus reducing the probability of drug collection at non-study sites), and standardized data capture across all sites. One limitation of this analysis is our reliance on MPR; in many ways, it is a crude measure of adherence. Although simple to calculate, it does not describe the actual ingestion of medication or the pattern of non-adherence (e.g. frequency, duration). Patient outcomes in this urban population may also not be representative of those in rural areas, where a growing number of programs are now expanding in Africa. Further work is needed to understand the role of adherence measurements such as MPR in such settings. Lastly, we were unable to fully account for the impact of food supplementation programs that were slowly rolled out in Lusaka over the observation period. Recent work demonstrated a clear impact of food supplementation on individual-level adherence; however, immunologic and clinical outcomes were unchanged at 6 and 12 months following ART initiation. Whether food supplementation might have an impact on survival is unknown.42

In summary, we demonstrate that MPR correlates with patient outcomes in the settings of rapid service scale-up, task shifting and high disease burden. Our findings are thus applicable to the many urban public sector programs in Africa seeking to expand services in the face of significant resource constraint. Although 80% MPR appears to be an important threshold for clinical outcomes and survival, its utility for individual patient care may be limited. MPR thresholds that correlate with virologic failure and viral drug resistance should be delineated, given their direct relevance to clinical care.

Funding

Multi-country grant to the Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement U62/CCU12354) through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, and a grant for Operations Research for AIDS Care and Treatment in Africa from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (2005047). Additional investigator salary or trainee support is provided by the National Institutes of Health (K01-TW06670; K23-AI01411; P30-AI027767; D43-TW001035); Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award (2007061). The findings and conclusions included herein are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and health personnel from the participating Lusaka clinics for providing this important information. We also acknowledge teams from the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Global AIDS Program (Lusaka, Zambia), and the Zambian Ministry of Health for the development, implementation and oversight of the electronic medical record system used for data collection. We thank the Zambian Ministry of Health for consistent and high level support of operations research surrounding its national HIV care and treatment program.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sethi AK, Celentano DD, Gange SJ, Moore RD, Gallant JE. Association between adherence to antiretroviral therapy and human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1112–18. doi: 10.1086/378301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moatti JP, Spire B, Kazatchkine M. Drug resistance and adherence to HIV/AIDS antiretroviral treatment: against a double standard between the north and the south. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 3):S55–61. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406003-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wainberg MA, Friedland G. Public health implications of antiretroviral therapy and HIV drug resistance. JAMA. 1998;279:1977–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harries AD, Nyangulu DS, Hargreaves NJ, Kaluwa O, Salaniponi FM. Preventing antiretroviral anarchy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2001;358:410–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieuwkerk PT, Sprangers MA, Burger DM, et al. Limited patient adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection in an observational cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1962–68. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents in Resource-Limited Settings: Towards Universal Access. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Press N, Tyndall MW, Wood E, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Virologic and immunologic response, clinical progression, and highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):S112–17. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. AIDS. 2002;16:1051–58. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy assessed by pharmacy claims predicts survival in HIV-infected South African adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:78–84. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225015.43266.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orrell C, Bangsberg DR, Badri M, Wood R. Adherence is not a barrier to successful antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2003;17:1369–75. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200306130-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296:679–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill CJ, Hamer DH, Simon JL, Thea DM, Sabin LL. No room for complacency about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2005;19:1243–49. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180094.04652.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross R, Yip B, Lo Re V, III, et al. A simple, dynamic measure of antiretroviral therapy adherence predicts failure to maintain HIV-1 suppression. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1108–14. doi: 10.1086/507680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossberg R, Zhang Y, Gross R. A time-to-prescription-refill measure of antiretroviral adherence predicted changes in viral load in HIV. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairley CK, Permana A, Read TR. Long-term utility of measuring adherence by self-report compared with pharmacy record in a routine clinic setting. HIV Med. 2005;6:366–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296:782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton-Moore C, Mubiana-Mbewe M, Cantrell RA, et al. Clinical outcomes and CD4 cell response in children receiving antiretroviral therapy at primary health care facilities in Zambia. JAMA. 2007;298:1888–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambian Ministry of Health. Antiretroviral Therapy for Chronic HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: New ART Protocols May 2007. Lusaka, Zambia: Printech Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fusco H, Hubschman T, Mweeta V, et al. Electronic Patient Tracking Supports Rapid Expansion of HIV Care and Treatment in Resource-Constrained Settings [Abstract MoPe11.2C37]. 2005, Rio de Janiero, Brazil: 3rd IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krebs DW, Chi BH, Mulenga Y, et al. Community-based follow-up for late patients enrolled in a district-wide programme for antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Care. 2008;20:311–17. doi: 10.1080/09540120701594776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Managed Care. 2005;11:449–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dezii CM. Persistence with drug therapy: a practical approach using administrative claims data. Managed Care. 2001;10:42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidle PJ, Wamai N, Solberg P, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a home-based AIDS care programme in rural Uganda. Lancet. 2006;368:1587–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman JD, Cantrell RA, Mulenga LB, et al. Simple adherence assessments to predict virologic failure among HIV-infected adults with discordant immunologic and clinical responses to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:1031–35. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zachariah R, Fitzgerald M, Massaquoi M, et al. Risk factors for high early mortality in patients on antiretroviral treatment in a rural district of Malawi. AIDS. 2006;20:2355–60. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801086b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of martingale-based residuals. Biometrika. 1993;80:557–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wools-Kaloustian K, Kimaiyo S, Diero L, et al. Viability and effectiveness of large-scale HIV treatment initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa: experience from western Kenya. AIDS. 2006;20:41–48. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196177.65551.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sieleunou I, Souleymanou M, Schonenberger AM, Menten J, Boelaert M. Determinants of survival in AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy in a rural centre in the Far-North Province, Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;14:36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, et al. Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d’Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008;22:873–82. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f768f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulder DW, Nunn AJ, Kamali A, Nakiyingi J, Wagner HU, Kengeya-Kayondo JF. Two-year HIV-1-associated mortality in a Ugandan rural population. Lancet. 1994;343:1021–23. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunn AJ, Mulder DW, Kamali A, Ruberantwari A, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Whitworth J. Mortality associated with HIV-1 infection over five years in a rural Ugandan population: cohort study. BMJ. 1997;315:767–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7111.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sewankambo NK, Gray RH, Ahmad S, et al. Mortality associated with HIV infection in rural Rakai District, Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14:2391–400. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bisson GP, Gross R, Bellamy S, et al. Pharmacy refill adherence compared with CD4 count changes for monitoring HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:939–41. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin M, Del Cacho E, Codina C, et al. Relationship between adherence level, type of the antiretroviral regimen, and plasma HIV type 1 RNA viral load: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:1263–68. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris MB, Chapula BT, Chi BH, Mwango A, Chi HF, Mwanza J, et al. Use of task-shifting to rapidly scale-up HIV treatment services: experiences from Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffar S, Govender T, Garrib A, et al. Antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: public health research priorities. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:295–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puccio JA, Belzer M, Olson J, et al. The use of cell phone reminder calls for assisting HIV-infected adolescents and young adults to adhere to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a pilot study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:438–44. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visnegarwala F, Rodriguez-Barradass MC, Graviss EA, Caprio M, Nykyforchyn M, Laufman L. Community outreach with weekly delivery of anti-retroviral drugs compared to cognitive-behavioural health care team-based approach to improve adherence among indigent women newly starting HAART. AIDS Care. 2006;18:332–38. doi: 10.1080/09540120500162155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samb B, Celletti F, Holloway J, Van Damme W, De Cock KM, Dybul M. Rapid expansion of the health workforce in response to the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2510–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cantrell RA, Sinkala M, Megazinni K, et al. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:190–95. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]