Abstract

Introduction

Resuscitation goals for septic shock remain controversial. Despite the normalization of systemic hemodynamic variables, tissue hypoperfusion can still persist. Indeed, lactate or oxygen venous saturation may be difficult to interpret. Our hypothesis was that a gastric intramucosal pH-guided resuscitation protocol might improve the outcome of septic shock compared with a standard approach aimed at normalizing systemic parameters such as cardiac index (CI).

Methods

The 130 septic-shock patients were randomized to two different resuscitation goals: CI ≥ 3.0 L/min/m2 (CI group: 66 patients) or intramucosal pH (pHi) ≥ 7.32 (pHi group: 64 patients). After correcting basic physiologic parameters, additional resuscitation consisting of more fluids and dobutamine was started if specific goals for each group had not been reached. Several clinical data were registered at baseline and during evolution. Hemodynamic data and pHi values were registered every 6 hours during the protocol. Primary end point was 28 days' mortality.

Results

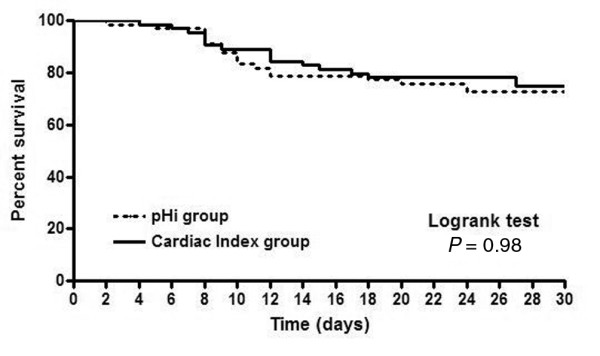

Both groups were comparable at baseline. The most frequent sources of infection were abdominal sepsis and pneumonia. Twenty-eight day mortality (30.3 vs. 28.1%), peak Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System scores (32.6 ± 6.5 vs. 33.2 ± 4.7) and ICU length of stay (12.6 ± 8.2 vs. 16 ± 12.4 days) were comparable. A higher proportion of patients exhibited values below the specific target at baseline in the pHi group compared with the CI group (50% vs. 10.9%; P < 0.001). Of 32 patients with a pHi < 7.32 at baseline, only 7 (22%) normalized this parameter after resuscitation. Areas under the receiver operator characteristic curves to predict mortality at baseline, and at 24 and 48 hours were 0.55, 0.61, and 0.47, and 0.70, 0.90, and 0.75, for CI and pHi, respectively.

Conclusions

Our study failed to demonstrate any survival benefit of using pHi compared with CI as resuscitation goal in septic-shock patients. Nevertheless, a normalization of pHi within 24 hours of resuscitation is a strong signal of therapeutic success, and in contrast, a persistent low pHi despite treatment is associated with a very bad prognosis in septic-shock patients.

Introduction

The subject of the best resuscitation goal for septic shock is still controversial [1-5]. The early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) trial showed that an aggressive resuscitation protocol aimed at normalizing central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2), may improve patient outcome if started early in the pre-ICU setting [2]. Nevertheless, the very low ScvO2 values in the EGDT trial, contrast with the findings of several ICU studies [6-8]. Moreover, a multicentric Italian study showed no advantage of resuscitating against mixed venous oxygen saturation (SmvO2) > 65% in critically ill patients with up to 48 hours of shock evolution [3]. In addition, physiological interpretation of lactate and central venous oxygen saturation as perfusion parameters may be difficult in some clinical settings, and both are not specific or sensitive markers of tissue hypoperfusion [9,10]. Moreover, it is not clear whether perfusion parameters are reliable if pursued late in the ICU setting [3,8].

In this context, gastric tonometry, a technique that indirectly assesses gastric mucosal perfusion, appears to be an attractive alternative. Low gastric intramucosal pH (pHi) is a sensitive marker of splanchnic hypoperfusion and a good predictor of poor outcome in critically ill patients [11,12], but no study specifically testing its potential role as a resuscitation goal in septic shock has been reported.

Ten years ago, we conducted a yet-unpublished, multicenter randomized controlled study comparing intramucosal gastric pH (pHi) versus cardiac index (the latter representing macrohemodynamic parameters) as therapeutic objectives in septic-shock patients, with the hypothesis that pHi-guided resuscitation may improve survival. (Fernando Palizas, Arnaldo Dubin, Tomas Regueira, Alejandro Bruhn, Elias Knobel, Silvio Lazzeri, Natalio Baredes and Glenn Hernández, unpublished data). Since then, the controversial issue of the best resuscitation goal for septic shock has not been resolved [7,8], and therefore, we considered clinically relevant to present our data testing an important physiologic marker of regional perfusion such as gastric tonometry.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all centers involved. All participants or their relatives signed an informed consent form before being enrolled in the study. The study was conducted from July 1998 through May 2000 in six closed intensive care units from Chile, Argentina and Brazil.

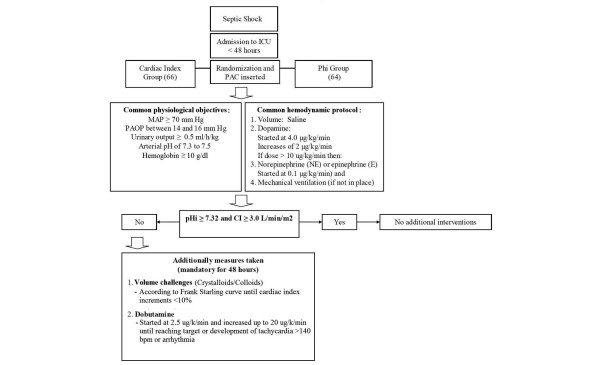

All adult patients fulfilling criteria for septic shock according to the ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference [13] within 48 hours of ICU admission were considered and selected if they were in a 12-hour time window. Exclusion criteria were: terminal illness with the patient expected to die within 28 days, irreversible neurologic impairment, and contraindication for nasogastric tube placement. Randomization was done by the central coordinator center. All patients were initially treated to normalize macrohemodynamic parameters for 2 to 4 hours (Figure 1), especially a mean arterial pressure or 70 mm Hg or greater, and were randomized thereafter to a goal-directed therapy aimed at a gastric mucosal pHi of 7.32 or greater (pHi group) or a cardiac index of 3.0 L/min/m2 or more (CI group). This later value was selected to prevent low systemic flow in this group [3]. A pulmonary artery catheter was placed in all patients, and additionally, patients assigned to the pHi group received a gastric tonometer. Measurements of pHi were obtained with a tonometer (TRIP NGS catheter; Tonometrics, Inc., Worcester, MA, USA) consisting of a gas-permeable silicone balloon located at the distal end of a conventional nasogastric tube. The silicone balloon is filled with saline, and carbon dioxide diffuses and equilibrates between the mucosa and the saline solution in the balloon to a steady state in 30 to 90 minutes. The solution is sampled anaerobically and adjusted to a steady-state carbon dioxide (PCO2 SS). The measurement of arterial bicarbonate from a simultaneously obtained arterial blood gas sample allows calculation of the pHi by using a modified Henderson-Hasselbach equation

Figure 1.

Septic-shock resuscitation protocol.

All patients received H2-receptor antagonists, and enteral feeding was avoided throughout the study period.

All patients received initial resuscitation aimed to normalize macrohemodynamic parameters and to maintain certain clinical variables within physiologic limits, as shown in Figure 1. Additional steps (mainly fluids to reach a plateau phase in the Starling curve and dobutamine) were taken if the specific goal for each group was not achieved (Figure 1). This hemodynamic management strategy was mandatory for the first 48 hours of the study and recommended but not required, later. The PAC and tonometer were removed once the resuscitation goal was maintained for 24 hours and if patients were considered stable by the supervising ICU staff.

Several clinical and demographic data, including age, sex, cause of sepsis, admission APACHE II (Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation) score, and daily SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) and TISS scores were registered. Patients were followed up for a maximum of 28 days. Hemodynamic data including cardiac index, vasoactive drugs dose, and pHi in the corresponding group were registered every 6 hours.

Statistical analysis

The primary study end point was 28-day mortality. Considering a two-sided type I error rate of 5%, and a power of 80%, we calculated that a sample size of 128 patients was required to permit the detection of a reduction in ICU mortality from 40 to 20%. Primary analysis was carried out on an intention-to-treat basis; Kaplan–Meier estimates of mortality was used to describe the relative risk of death. Differences between the two groups were assessed with the use of Student's t-test and the chi-square test as corresponded. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were determined for mortality prediction with pHi and cardiac index values at different time points of resuscitation. Data are presented as mean ± SD. A value of P < 0.05 with a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant.

Results

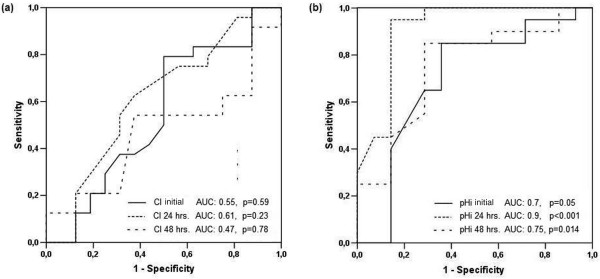

One-hundred thirty consecutive patients with septic shock were enrolled and randomly assigned to the CI (66 patients) or pHi groups (64 patients). No differences between groups were found at baseline, except for a higher SOFA score in the pHi group (Table 1). The most common diagnoses were abdominal sepsis in 88 (68%) and pneumonia in 26 (20%) patients. Overall, 28-day mortality (30.3 vs. 28.1%; log-rank test, P = 0.98) (Figure 2), peak TISS scores (32.6 ± 6.5 vs. 33.2 ± 4.7; P = 0.52) and ICU length of stay (12.6 ± 8.2 vs. 16 ± 12.4 days; P = 0.07) were comparable. The cumulative survival curves are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data at baseline

| CI group (n = 66) |

pHi group (n = 64) |

P value | |

| Age (yr) | 57.4 ± 15.9 | 59.9 ± 15.9 | 0.38 |

| Gender (male/female) | 42/24 | 33/31 | 0.2 |

| Admission APACHE II | 18.5 ± 3.8 | 19.4 ± 5.6 | 0.3 |

| Admission SOFA | 8.8 ± 2.7 | 10.6 ± 3.6 | < 0.05a |

| Sepsis source | |||

| Abdominal n/(%) | 43 (65) | 45 (70) | |

| Pneumonia n/(%) | 15 (23) | 11 (17) | |

| Urinary n/(%) | 4 (6) | 6 (9) | |

| Others n/(%) | 4 (6) | 2 (3) |

CI = Cardiac index; SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment score.

aP < 0.05 considered significant. Unpaired t test and chi-square test for P values.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for both groups.

A higher proportion of patients exhibited values below the specific target at baseline in the pHi group compared with the CI group (32 of 64 (50%) versus seven of 66 (10.9%); P < 0.001). Of 32 patients with a pHi less than 7.32 at baseline, only seven (22%) normalized this parameter after 24 hours of resuscitation, and all of these patients survived. The mean values of cardiac index and pHi at different time points are shown in Table 2. We could not demonstrate any difference between CI and pHi groups in the intensity of treatment as reflected by comparable peak TISS scores (32.6 ± 6.5 vs. 33.2 ± 4.7; P = 0.52), but a trend was observed to more dobutamine use (31.8 vs. 48.4%; P = 0.07), with higher peak doses (8.8 ± 10.6 vs. 13.4 ± 7.8 μg/kg/min; P = 0.1) in the pHi group. pHi was a better predictor of outcome than was cardiac index (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of target values between survivors and nonsurvivors in both groups at different time points

| Admission (n) | 24 hours (n) | 48 hours (n) | |

| CI group | |||

| Cardiac index | |||

| Total (66) | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 4.05 ± 0.9 | 3.57 ± 1.3 |

| Survivors (46) | 4.46 ± 1.02 (46) | 4.18 ± 0.7 (44) | 3.56 ± 1.5 (24) |

| Nonsurvivors (20) | 3.94 ± 1.20 (20) | 3.78 ± 1.0 (20) | 3.58 ± 0.9 (16) |

| Pa | NS | NS | NS |

| pHi group | |||

| pHi | |||

| Total (64) | 7.3 ± 0.12 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 7.28 ± 0.12 |

| Survivors (46) | 7.32 ± 0.12 (46) | 7.36 ± 0.06 (46) | 7.33 ± 0.10 (20) |

| Nonsurvivors (18) | 7.26 ± 0.12 (18) | 7.19 ± 0.10 (18) | 7.20 ± 0.13 (14) |

| Pb | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.003 |

| Cardiac Index | |||

| Total (64) | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4.04 ± 1.5 |

| Survivors (46) | 3.66 ± 0.9 (46) | 3.83 ± 1.1 (46) | 3.47 ± 0.80 (20) |

| Nonsurvivors (18) | 4.23 ± 1.4 (18) | 3.93 ± 1.2 (18) | 4.27 ± 1.29 (14) |

| Pc | NS | NS | NS |

aCI of survivors vs. nonsurvivors in the CI group; bpHi of survivors vs. nonsurvivors in the pHi group; cCI of survivors vs. nonsurvivors in the pHi group.

A value of P < 0.05 is considered significant. Unpaired t-test for P values.

Figure 3.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for mortality for both groups at admission, at 24 hours, and at 48 hours.

Discussion

Our study failed to demonstrate any difference in survival of septic-shock patients treated with pHi or with the cardiac index as a guide of hemodynamic resuscitation. Nevertheless, our findings confirm previous reports about the prognostic value of a persistent low pHi [11,12]. In addition, although only 22% of patients with low admission pHi values had this parameter normalized after resuscitation, this fact was associated with a high probability of survival.

This prospective, randomized, controlled study is the first to evaluate the use of pHi as a resuscitation goal specifically in septic-shock patients. We hypothesized that these patients may benefit from organ perfusion–oriented resuscitation, because splanchnic circulation is particularly sensitive to cardiocirculatory changes in sepsis. Changes include a redistribution of blood flow away from the mucosa, constriction of the villus arteriole and microcirculatory derangements [14], which could be associated with hypoxia and with an increase in gut permeability [15-18].

Why does a physiologically sound goal fail to demonstrate any benefit when used as a therapeutic objective? Many possible explanations exist. First, our study could be underpowered to detect a real difference, but this is unlikely when observing the almost superimposed Kaplan–Meier curves. Second, pHi may be a proper goal but only for an earlier stage of septic shock. This factor can strongly influence results, as demonstrated by the example of the positive EGDT [2] versus the negative Italian multicenter [3] trials. Both were aimed at basically the same resuscitation goal (central or mixed venous oxygen saturation). Nevertheless, the former was used very early, in the pre-ICU setting, and the second, during late ICU management. Our study was similar in design to the Italian study, including patients after up to 48 hours of ICU stay. It is possible that during this period, patients may have been exposed to prolonged hypoperfusion before being randomized. This may have led to irreversible hypoxia or multiple organ dysfunctions in some patients. Similarly, Gutierrez et al. [11] showed that pHi-guided resuscitation of critically ill patients was successful only in patients admitted with normal pHi. Conversely, in patients with intramucosal acidosis on admission, the outcome failed to improve. This finding was ascribed to longer tissue hypoxia in this group.

A third potential factor is the relative ineffectiveness of treatments aimed at normalizing pHi. No study has unequivocally demonstrated a positive impact of specific therapies such as volume, different catecholamines, or vasodilators over gut mucosal perfusion [19,20]. Dobutamine has a relatively low therapeutic index, could be dangerous when used in high doses [4], and, in some cases, may be ineffective because unwanted effects (such as tachycardia or arrhythmias) preclude an optimal titration. This fact could explain why both groups used almost comparable doses of dobutamine and exhibited similar cardiac indices, although more patients in the pHi group were below target at baseline.

Although our study did not show a survival advantage of using pHi-guided resuscitation in septic-shock patients, our results are consistent with those of the studies of Gutierrez [11] and Ivatury [12], demonstrating that patients who reach or maintain a normal pHi after an aggressive resuscitation have a higher probability of survival.

Although our results could be considered negative, it is interesting to speculate about additional considerations. Except for the controversial EGDT trial in the early pre-ICU setting, no study has convincingly demonstrated an advantage of perfusion-oriented goals (such as lactate or SmvO2) over classic hemodynamic parameters as end points of resuscitation. Nevertheless, many proofs exist that "normal" hemodynamic parameters (including mean arterial pressure, cardiac index, oxygen transport) can coexist with profound tissue hypoperfusion or microcirculatory derangements [21,22]. Therefore, the actual standard of care is to resuscitate septic-shock patients until perfusion-related parameters such as clinical perfusion, lactate or ScvO2/SmvO2, are normalized [1]. One problem with this approach is that both lactate and ScvO2 may be difficult to interpret in some settings (for example, liver failure, epinephrine use, or early after intubation) [8,9]. Moreover, tissue hypoperfusion can be present in patients with normal ScvO2 values [12]

Gastric tonometry has been shown to be well correlated with splanchnic perfusion in different models of shock [23-29]. In this context, gastric tonometry may still have a role in assessing perfusion and guiding resuscitation therapy in some patients, in whom other markers such as lactate or ScvO2 may be misleading or confusing. A normalization of pHi within 24 hours of resuscitation is a strong sign of therapeutic success, and in contrast, a persistent low pHi despite treatment is associated with a very bad prognosis in septic-shock patients.

Our study was performed a decade ago. In the meantime, more insight has been gained into several technical and physiologic limitations of gastric tonometry that have precluded its further technologic development or clinical acceptance. However, its physiologic rationale has been recently validated in several experimental studies [14-19]. Gastric tonometry has also undergone a number of methodologic changes over the last decade, shifting from saline to automated gas tonometry, which incorporates the direct analysis of the intraluminal pCO2 and pCO2 gap. One of the potential pitfalls of pHi calculation is that it includes arterial bicarbonate, which is a systemic parameter not dependent on gut perfusion. Although the use of a pCO2 gap instead of pHi is more physiologically sound [30], we do not believe that this fact would have changed our results. Some controversial data exist about the validity of the pCO2 gap as a marker of splanchnic perfusion [31-33], and it has not been tested as a resuscitation goal. In addition, scarce evidence is found about its prognostic value [34], and no clinical study has demonstrated its superiority over pHi.

Our study has several limitations. First, the lack of data about fluid balance and SmvO2 may limit the interpretation of our results. Second, the use of the cardiac index as a resuscitation goal is questionable, because no "normal" values of CI can be recommended for any given clinical condition. Instead, the concept of adequate or inadequate cardiac index should be used, according to the adequacy of flow to real O2 demand [35]. Nevertheless, the cardiac index has not been shown to be inferior to other parameters when used as resuscitation goal [3]. Third, in more than 60% of our septic patients, the sepsis was of abdominal origin, in contrast to large epidemiologic data that show that the lung is the predominant source of sepsis worldwide. Therefore, we cannot assure that our results would have been the same in a larger, more typical ICU population.

Despite these limitations, we considered it important to report this study because (a) the controversy about the best resuscitation goal for septic shock still persists; (b) other potential perfusion or metabolic resuscitation goals, such as ScvO2 or lactate, may be very difficult to interpret in some settings; (c) the evolution of pHi after 24 hours of resuscitation provides a strong prognostic signal, which could be valuable for specific patients; and (d) gastric tonometry has been clearly validated and is still widely used in the experimental setting, providing a strong physiological signal that probably deserves to be further explored in the clinical arena.

Conclusions

Our study failed to demonstrate any survival benefit of using the pHi compared with the cardiac index as resuscitation goal in septic-shock patients. Nevertheless, a normalization of pHi within 24 hours of resuscitation is a strong signal of therapeutic success, and in contrast, a persistent low pHi despite treatment is associated with a very bad prognosis in septic-shock patients. Future studies should evaluate a potential adjunctive role of tonometry-guided resuscitation at earlier stages of septic shock.

Key messages

• A resuscitation strategy aimed at normalizing pHi offers no survival advantage compared with cardiac index–guided resuscitation in septic-shock patients.

• A normalization of pHi within 24 hours of resuscitation is a strong signal of therapeutic success during septic-shock resuscitation.

• A persistent low pHi despite treatment is associated with a very bad prognosis in septic-shock patients.

Abbreviations

ACCP: American College of Chest Physicians; APACHE II: Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation score; ATS: American Thoracic Society; CI: cardiac index; EGDT: Early Goal-Directed Therapy; PAC: pulmonary artery cathéter; pCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pHi: gastric intramucosal pH; ROC: receiver operator characteristic curve; SCCM: Society of Critical Care Medicine; ScvO2: central venous oxygen saturation; SmvO2: mixed venous oxygen saturation; SOFA: Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment; SS: steady state; TISS: Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FP conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. AD conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. EK participated in its coordination. TR helped to draft the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. AB recruited patients and helped to draft the manuscript. NB participated in its coordination and recruited patients. SL participated in its coordination and recruited patients. GH conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by institutional (departmental) grants for each participating center. The authors thank Dr. Guillermo Gutierrez, MD, PhD, for his valuable review of the manuscript.

See related commentary by Jakob, http://ccforum.com/content/13/3/147

Contributor Information

Fernando Palizas, Email: palizas2002@yahoo.com.ar.

Arnaldo Dubin, Email: arnaldodubin@speedy.com.ar.

Tomas Regueira, Email: tregueira@gmail.com.

Alejandro Bruhn, Email: abruhn@med.puc.cl.

Elias Knobel, Email: knobel@einstein.br.

Silvio Lazzeri, Email: silviolazzeri@yahoo.com.ar.

Natalio Baredes, Email: nbaredes@intramed.net.ar.

Glenn Hernández, Email: glennguru@gmail.com.

References

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, Calandra T, Dhainaut JF, Gerlach H, Harvey M, Marini JJ, Marshall J, Ranieri M, Ramsay G, Sevransky J, Thompson BT, Townsend S, Vender JS, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P, Latini R, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, Fumagalli R. A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. SvO2 Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1025–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MA, Timmins AC, Yau EH, Palazzo M, Hinds CJ, Watson D. Elevation of systemic oxygen delivery in the treatment of critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1717–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alia I, Esteban A, Gordo F, Lorente JA, Diaz C, Rodriguez JA, Frutos F. A randomized and controlled trial of the effect of treatment aimed at maximizing oxygen delivery in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Chest. 1999;115:453–461. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracht H, Hanggi M, Jeker B, Wegmuller N, Porta F, Tuller D, Takala J, Jakob SM. Incidence of low central venous oxygen saturation during unplanned admissions in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit: an observational study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R2. doi: 10.1186/cc5144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beest PA, Hofstra JJ, Schultz MJ, Boerma EC, Spronk PE, Kuiper MA. The incidence of low venous oxygen saturation on admission to the intensive care unit: a multi-center observational study in The Netherlands. Crit Care. 2008;12:R33. doi: 10.1186/cc6811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo R, Reade MC, Warrillow SJ. The pursuit of a high central venous oxygen saturation in sepsis: growing concerns. Crit Care. 2008;12:130. doi: 10.1186/cc6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. Lactate and shock state: the metabolic view. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:315–321. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000235208.77450.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee F, Vallet B, Mathe O, Parraguette J, Mari A, Silva S, Samii K, Fourcade O, Genestal M. Central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide difference: an additional target for goal-directed therapy in septic shock? Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:2218–2225. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez G, Palizas F, Doglio G, Wainsztein N, Gallesio A, Pacin J, Dubin A, Schiavi E, Jorge M, Pusajo J, et al. Gastric intramucosal pH as a therapeutic index of tissue oxygenation in critically ill patients. Lancet. 1992;339:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90002-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Islam S, Fueg A, Rohman M, Stahl WM. A prospective randomized study of end points of resuscitation after major trauma: global oxygen transport indices versus organ-specific gastric mucosal pH. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Baudry N, Duranteau J, Vicaut E. Microcirculation in intestinal villi: a comparison between hemorrhagic and endotoxin shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1526–1530. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2009065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer D, Creteur J, Silva E, Vincent JL. Effects of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine on the splanchnic circulation in septic shock: which is best? Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1659–1667. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063045.77339.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltebrand LB, Krejci V, Banic A, Erni D, Wheatley AM, Sigurdsson GH. Dynamic study of the distribution of microcirculatory blood flow in multiple splanchnic organs in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3233–3241. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuer CJ, Wilson MA, Steeb GD, Garrison RN. Microvascular vasoconstriction and mucosal hypoperfusion of the rat small intestine during bacteremia. Circ Shock. 1993;40:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltebrand LB, Krejci V, Sigurdsson GH. Effects of dopamine, dobutamine, and dopexamine on microcirculatory blood flow in the gastrointestinal tract during sepsis and anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1188–1197. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200405000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin A, Murias G, Sottile JP, Pozo MO, Baran M, Edul VS, Canales HS, Etcheverry G, Maskin B, Estenssoro E. Effects of levosimendan and dobutamine in experimental acute endotoxemia: a preliminary controlled study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:485–494. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0519-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomersall CD, Joynt GM, Freebairn RC, Hung V, Buckley TA, Oh TE. Resuscitation of critically ill patients based on the results of gastric tonometry: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:607–614. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer D, Creteur J, Dubois MJ, Sakr Y, Koch M, Verdant C, Vincent JL. The effects of dobutamine on microcirculatory alterations in patients with septic shock are independent of its systemic effects. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:403–408. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000198107.61493.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell MD, Donnino M, Clardy P, Talmor D, Shapiro NI. Occult hypoperfusion and mortality in patients with suspected infection. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1892–1899. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin A, Estenssoro E, Murias G, Canales H, Sottile P, Badie J, Baran M, Palizas F, Laporte M, Rivas Diaz M. Effects of hemorrhage on gastrointestinal oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1931–1936. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros M, Kaszaki J, Ordogh B, Nagy S. Intramucosal pH changes following complete segmental small intestinal ischemia, as compared with the effects of superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Eur Surg Res. 1994;26:76–86. doi: 10.1159/000129321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson JB, Kuttila K, Niinikoski J, Haglund UH. Subcutaneous and gut tissue perfusion and oxygenation changes as related to oxygen transport in experimental peritonitis. Circ Shock. 1993;41:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee JB, McJames SW. Use of gastric intramucosal pH as a monitor during hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock. 1994;43:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creteur J, De Backer D, Vincent JL. Monitoring gastric mucosal carbon dioxide pressure using gas tonometry: in vitro and in vivo validation studies. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:504–510. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderMeer TJ, Wang H, Fink MP. Endotoxemia causes ileal mucosal acidosis in the absence of mucosal hypoxia in a normodynamic porcine model of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1217–1226. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JA, Lacoma FJ, Kruse JA. Relationship between systemic oxygen supply dependency and gastric intramucosal PCO2 during progressive hemorrhage. J Trauma. 1998;44:696–700. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199804000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton MA, Mythen MG. Gastric tonometry: where do we stand? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:122–127. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA, Rico P, Garuba AK, Pinsky MR. Accuracy of mucosal pH and mucosal-arterial carbon dioxide tension for detecting mesenteric hypoperfusion in acute canine endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:462–466. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creteur J, De Backer D, Vincent JL. Does gastric tonometry monitor splanchnic perfusion? Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2480–2484. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusaro A, Russell JA, Walley KR, Takala J. Gastric-arterial PCO2 gradient does not reflect systemic and splanchnic hemodynamics or oxygen transport after cardiac surgery. Shock. 2000;14:13–17. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman G, Berlot G, Kahn RJ, Vincent JL. Combined measurements of blood lactate concentrations and gastric intramucosal pH in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1184–1193. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL. The International Sepsis Forum's frontiers in sepsis: high cardiac output should be maintained in severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2003;7:276–278. doi: 10.1186/cc2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]