Mutilation of the most extruding parts of the face (nose, ears, lips) has always meant a very severe impairment, not only of the body, but of the individual’s personality, since it results in a permanent alteration in the most noble and expressive part of the human body. The nose, in particular, was considered, already in very ancient times, the principal element of one’s physiognomy not only as far as concerns the strictly aesthetic aspects (and classic Greek art has offered us countless examples), but also because the form, the aspect itself, appeared to reflect particular qualities of the character, of the psychology of the individual, a topic which, in the past, fascinated many men of great culture, from Michele Savonarola to Gerolamo Cardano, from Giovanni Battista Della Porta to Cesare Lombroso.

The importance of the nose, purely as an aesthetic element, as a symbolic value or as an expression of the character of a subject, inspired, over the centuries, not only figurative or plastic art, but also the theatre (Edmond Rostand), poetry (Antonio Guadagnoli) (Fig. 1), philosophy (Blaise Pascal), narration (Edmond About, Laurence Sterne, Nicolai Gogol) and even music (Dimitri Shostakovich).

Fig. 1.

An illustration from Il naso by Antonio Guadagnoli from Arezzo. Poesie giocose di Antonio Guadagnoli, Lugano, 1839.

Clearly, patients who, submitted to this type of mutilation, felt deprived of part of their very personality, attempted, in every possible way, to disguise the lesion, and already even in very ancient times, reconstructive surgery or application of a prosthesis were sought after.

While, today, severe loss of any part of the nasal arch is fairly rare and is observed only as a result of accidental traumatic events or destructive processes of neoplastic, specific or granulomatous processes, in ancient times, this type of mutilation was much more frequent. Contributing to this increased number were other causes related to certain historic periods and to the particular local customs. Often amputation of the nose was the result of judicial punishment, or may have resulted from a duel or from fighting in a battle, or, in some cases, was inflicted as revenge by a jealous lover, or in others was the consequence of a strange form of self mutilation.

Judicial punishment

Mutilation of protruding parts of the body (lips, tongue, breast, hands, genitals, nose, ears) was performed as judicial punishment, at different times and in various places. Proof can be gained from many ancient sources: from the Hammurabi code to the Egyptian papyri in the dynastic period, from the writings of Hindu vedic medicine described by Susruta and Charaka to the descriptions of the habits of the populations of Pre-Colombian America (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This zapotecan illustration depicts surgery on, or maybe amputation of, the nose. Codex Nuttal, Tav. 52.

Amputation of the nasal pyramid, in some ancient civilisations, was considered legal punishment for certain misdeeds. In Egypt, at the time of the Pharaoh Ramses III (XX dynasty, 1192-1166 BC), a famous trial was held involving those responsible for the so-called “great harem conspiracy” some of whom were condemned to mutilation of the nose and ears, including two of the judges, responsible for having succumbed to the seduction of some of the women involved in the plot. Indeed, more than one century earlier, General Horemheb, who had become Pharaoh during the XVIII dynasty, had made a decree which punished, with deportation and amputation of the nose, magistrates who had taken advantage of their role.

The Penal Code in Egypt, at the time of the Pharaohs, foresaw this type of mutilation, also for adultery, a punishment that was maybe rarely carried out judging from the fact that evidence of these lesions has rarely been found in the mummies.

Could it be that either the charges were rare or the judges were particularly tolerant or the Egyptian wives were true examples of virtue? This opinion concerning women’s morals was certainly not upheld by Herodotus, the famous historian on the Egyptian civilization who lived in the 5th Century BC. In this respect, he stated: “To a Pharaoh, who had become blind, it was predicted that he would have been able to regain his sight if he bathed his eyes, several times a day, with the urine of an absolutely faithful woman. The prescription, seemingly simple was, in actual fact, somewhat difficult to realise as much time passed by before a bride with these qualities could be found”.

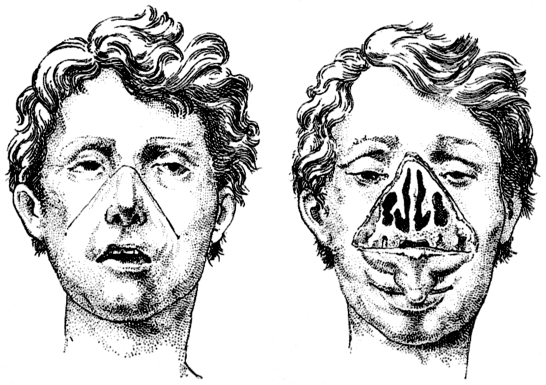

In ancient times, the laws in various countries established amputation of the nose, as corporal punishment, for misdeeds such as adultery, taking advantage of his position, or unfaithfulness. This was a fairly widespread punishment, particularly in India and the oriental countries, indeed the Indian method of plastic reconstruction of the nose dates back a very long time. Spreading of these types of lesions was also due to the fact that sovereigns mutilated, in this same fashion, slaves and any lower class individuals even for futile motives, whilst this punishment should have been applied only for crimes of a certain importance (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of two pictures clearly showing the devastating effect that amputation of the nose can have upon the face (from Willemot, 1981 3).

The practice of amputating the nose as punishment for adultery was widespread also amongst other populations and was performed, even if rarely, also by the Greeks and the Romans, but it was the Byzantines, in particular and after them the Arabs who used this practice, and in societies so male-orientated, often the husband whose wife had been unfaithful was instructed to act as executioner. In the case of adultery, only the woman was mutilated, the man could usually get away with 100 strokes of the cane or pay a fine.

Rhinotomy was also used against political opponents. A typical case was that of the Emperor Justinian II, who was replaced in 695 by General Leonzio who had gained the power after having had him mutilated. Justinian, called, on account of the nasal amputation, Rinotmète, ten years later came back on the Byzantium throne.

Nasal mutilations were decreed by law also in Europe: Childebert II, at the end of the 6th Century, condemned some subjects, to this punishment, who had been responsible for a conspiracy against him (Gregory of Tours, MGH X,18) and Frederick II (1194-1250) inflicted the same punishment on those guilty of adultery and also those guilty of having favoured prostitution, only Alphonso The Sage (1221-1284), King of Castile and Leon objected to this barbaric violence, enforcing a decree forbidding punishments of this kind, but it was an exception 1 2.

In the 16th Century, a large number of highway robbers had invaded Rome and the surrounding countryside, but Sixtus V successfully managed to get rid of them with a very effective deterrent consisting in a decree which would have condemned them to rhinotomy; in England, in the 16th and 17th Century, whoever wrote or spread libel referring to the King was condemned to amputation of the nose or ears. Even Daniel Defoe (1666-1731), the famous author of Robinson Crusoe, managed, at the very last moment, to avoid being submitted to this infamous punishment to which he had been condemned on account of the pamphlets that he produced against the King 2 3.

The war

The traumas suffered in battle, particularly in the long period in which it was mainly a matter of fighting with sidearms, were certainly one of the causes, if not the principal cause, of mutilations of the nose.

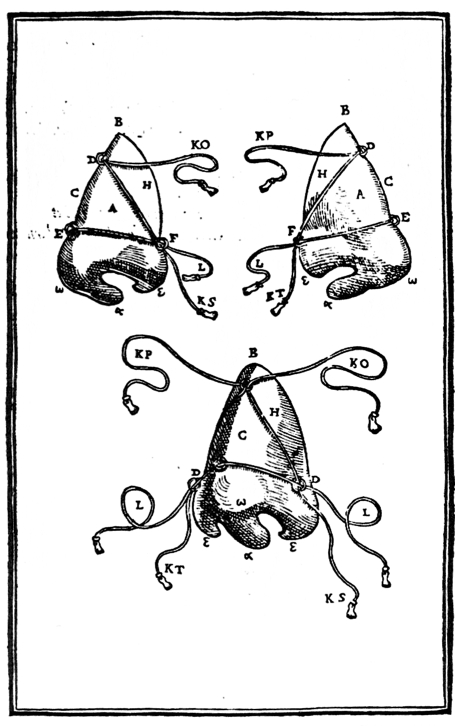

The frequency of this type of wound is clearly documented in a curious book by the alchemist doctor, Leonardo Fioravanti (1518-1588), a follower of Paracelso: Il tesoro de la vita humana (The treasure of human life) 4. In this book, the story is told of two Bolognese gentlemen, one “Who upon the retreat of Sarravalle in Lombardy had had his nose mutilated, fighting with the enemy” and the other, part of the Albergati family, “who had also had his nose cut off by a mercenary soldier”. According to the Author, mutilations of this type were a fairly common result of fighting, but the main point of interest in this story is, above all, the confirmation that repair of these lesions in the 16th Century was usually assigned to families of empirical Italian surgeons, such as Vianeo from Tropea or Branca from Sicily 5. They had, in fact, devised a secret method of reconstructive rhinoplasty which was passed down from father to son before Gaspare Tagliacozzi, from Bologna, codified the operation in his famous book De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem (1597) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A famous engraving showing the Italian method used, at the time, in reconstruction of the nose. From Gaspare Tagliacozzi: De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem. Venice: Bindoni 1597.

The duels

Duels with sidearms were another fairly frequent cause of nasal amputation.

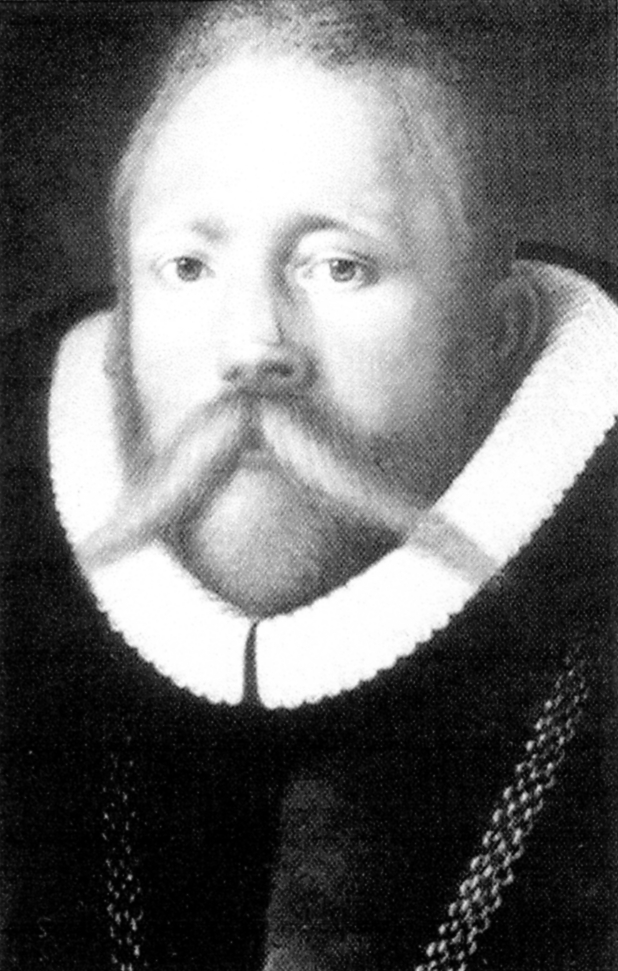

The famous Danish astronomer Ticho Brahe (1546-1601), Master of Kepler, had a particularly fiery character and at only 20 years of age had had his nose cut in a duel with a young man of his own age (Fig. 5) 6. Interest in this event stems from the fact that the loss of substance was masked for the rest of one’s life with implantation of a prosthesis made from a thin piece of painted metal (an alloy of gold and silver) that the patient kept in place with a glue-like substance and which is still visible to this day in some portraits of the great astronomer who, for this reason, became known as “the man with the golden nose”.

Fig. 5.

Portait of the famous astronomer Ticho Brahe showing, on the left side of the nose, the thin prosthesis that he wore throughout his life (from Pirsig, Willemot 2001 6).

The custom of duels continued, even if prohibited by law, during Medieval times up until the end of the 19th Century. In the report by Hoffacher, who in the 1820’s acted as Physician in the event of duels, in Heidelberg, various cases of amputation of the nose are described, some of which related to a kind of students’ fight (mensur) which was very popular in the German University towns in the 19th Century, and the scars of which, on the face, were to witness, for always the courage of that person 2.

Sometimes, the arms used in the duel were not of the type approved by the Code of Honour and, in this respect, it is worthwhile quoting a curious occurrence described by René Croissant de Garengeot in his surgical treatise of 1748 7. During a fight which broke out between two drunken soldiers who had just come out of a tavern, one of the two men, bit his opponent and tore away the entire cartilaginous part of the nose. The peculiarity of this episode refers, not only to the unusual mode of the mutilation, but also to the fact that the anatomical portion torn away was picked up off the ground, washed in hot wine and reimplanted, by a certain Dr Galin, who fixed it in place, without suturing, but with a glue, and, as if by a miracle, it remained permanently attached. An identical situation was reported by Leonardo Fioravanti 4 who described how he picked up the chopped off nose of a gentleman during a duel and how he cleaned it with his urine, then immediately proceeded with re-implantation which, he reported, showed perfect results. On the other hand, if we are to accept a thesis by George Martin, in Paris, dating back to 1875, this event should not be considered exceptional. This author, in fact, collected 25 cases appearing in the medical literature, in general resulting from duels, in which a portion of the nose which had been completely detached was immediately re-implanted with favourable results 3.

Self-mutilations

Self-inflicted rhinotomy was used in ancient times by women who, by making themselves look repulsive, avoided being sexually attacked. This sacrifice was sometimes performed in a very horrendous way by religious communities when convents were attacked by invaders. In the 9th Century, the nuns in the St. Cyr Monastry in Marseilles, together with the Abbess Eusebia, performed self-inflicted mutilations of the nose in the hope that they would be spared by the Saracens who were invading the convent. The attempt did, indeed, spare them from sexual attacks but cost the lives of the nuns, all of whom were assassinated 2.

The same fate awaited the nuns of Saint Clare in the City of Acri in 1291 1.

Revenge

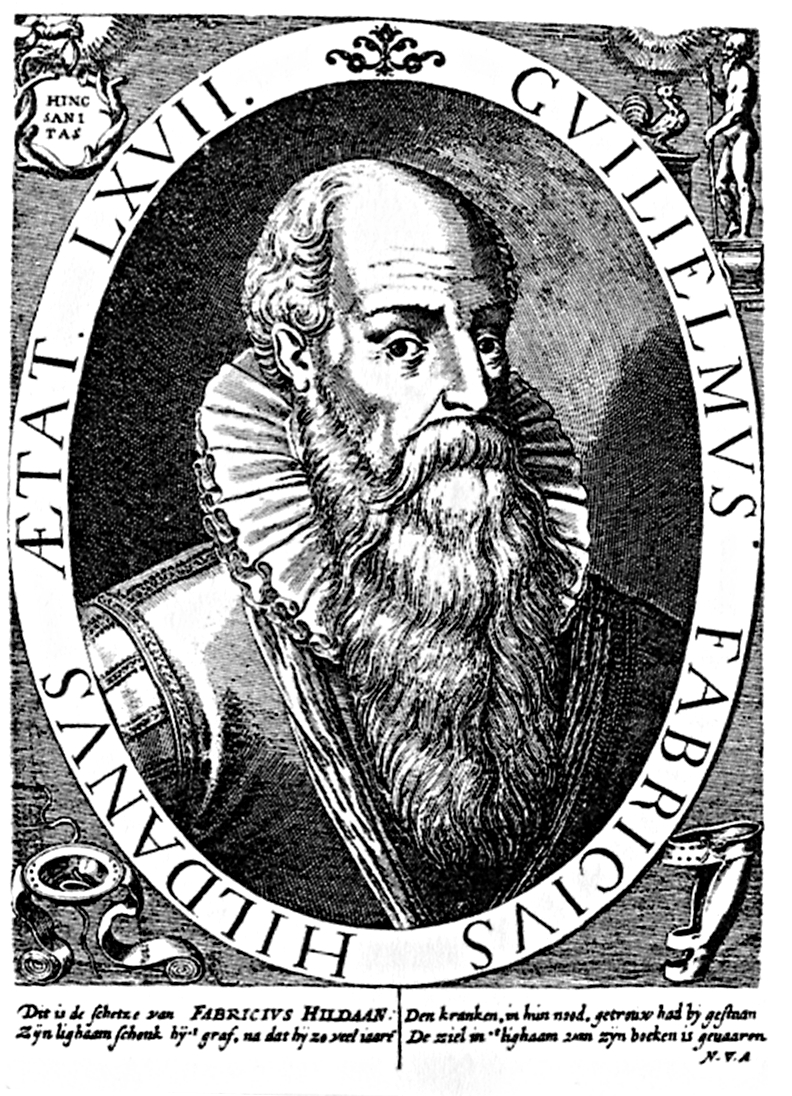

If sometimes amputation of the nose was self-inflicted in order to avoid sexual attack, it was also possible that the mutilation was due to revenge for a sexual attack that had been unsuccessful. This is, in fact, the case of Susanna the Chaste described by Fabritius Hildanus in the Observationum et curationum chirurgicarum centuriae 2 (Fig. 6). This is how the story goes: “Anno 1590 cum dux Sabaudiae Geneviensibus bellum inferret, incidit in manu militum puella quaedam casta et pia, Susanna N. nomine, quam cum stuprare frustra tentassent, atque hac de re maxima ira perciti nasum ipsi absciderunt”. Certainly, the worst punishment for a woman was amputation of the nose which would have ruined, beyond repair, a beautiful face transforming it into a horrendous and repulsive mask.

Fig. 6.

Wilhelm Fabry Hildanus (1577-1634), one of the greatest surgeons of the time, who performed numerous studies focusing on nose wounds and rhinoplasty.

This was, therefore, the most barbaric revenge, much more so than a simple cut on the cheek, that a rejected or betrayed lover might have done. Fortunately, such a criminal act occurred only very rarely.

As far as concerns the clinical case described above, results, according to Hildanus, were satisfactory as the female patient, operated upon by John Griffon, using the technique described by Tagliacozzi, had good results from an aesthetic point of view.

Rhinotomy may well have been due to revenge on the part of the husband who had been betrayed and this type of retaliation was tolerated already by Roman law (Marziale, Epigrammi II,83; III,85) and could be inflicted upon either of those committing adultery. Sometimes, the offended party limited the reaction to requesting compensation, from the rival, in the form of money, instead of amputation of the nose.

In some cases, this type of lesion was caused by the reaction of a jealous woman, who, in this way, got her revenge upon the rival. An example of this kind of behaviour is illustrated by a famous surgeon, in Paris, in the 18th Century, Pierre Dionis, when he described how the wife of a Notary, well-known in the city, believed that her husband was being unfaithful, trapped by the graces of a beautiful lady butcher from Fauburg St. Germain. The wife affronted this rival in her little shop and taking hold of a very sharp knife, amputated her nose which remained attached to her face merely by a small strip of tissue. Dionis, immediately consulted, managed to stitch the stump in place, which, in his opinion, resulted in a very favourable outcome 9.

Sometimes, mutilation of the nose was practised, on a large scale, as an act of revenge against prisoners of war, responsible for having been particularly ruthless in a siege or invasion.

This is, in fact, what happened in the City of Kirhipu in Nepal, referred to as the “City of the chopped off noses”, the inhabitants were, indeed, punished in this way by the King of Gorkha, Prizi Narayan 1. Likewise, in slightly more modern times, in 1876, during the war between Russia and Turkey, many of the Sultan’s soldiers had their noses amputated for revenge by the Bulgarian invaders. Quite soon, thereafter, the enemy having been driven back and overcome, the Turkish Sultan made a gift to each of those mutilated, rewarding them with a nasal prosthesis in pure silver which they displayed with pride in the streets of Istanbul, like a decoration of great value 10.

Conclusions

It is worthwhile taking a closer look at some of the exceptional historical events outlined here.

Clearly amputation of the nose provoked, in a person submitted to this torture, very severe disfigurement, not only physical but also psychological, inducing those involved to isolate themselves, keeping themselves as much as possible out of the view of other people.

For this reason, the person had to attempt to overcome this situation in some way and the only way was to wear a mask or a prosthesis, either fixed or removable, or attempt reconstructive surgery. This was absolutely necessary in order to avoid showing off a face that was so disfigured that it provoked a sense of horror. Such a strong sense of horror that it induced the Theolegian Sanchez to sustain that a mutilation of that kind would allow annulment of a marriage to be decreed 11. Indeed, some biblical references assigned great importance to particularly evident alterations of the nose: in fact, these would even have prevented access to priesthood (Leviticus XXI, 18).

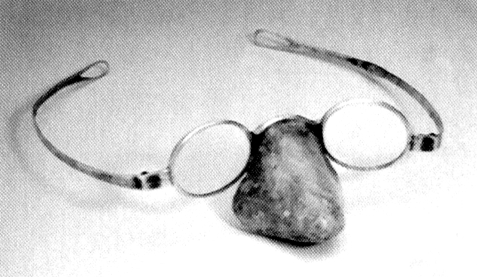

The means most frequently used to hide the loss of substance in the middle of the face have been, over the Centuries, nasal prosthesis and reparative surgery. Prostheses were usually made from various materials such as leather, wood, paper mâché or metal (particularly alloys of gold and silver or of gold and copper). These would have been kept in place with cords, as suggested by Ambroise Paré 12, or they may have been incorporated into the frames of glasses as is the custom nowadays in Carnival masks (Figs. 7, 8).

Fig. 7.

16th Century nasal prosthesis in paper mâché 12.

Fig. 8.

18th Century nasal prosthesis anchored to spectacle frames (from Pirsig, Willemot 2001 6).

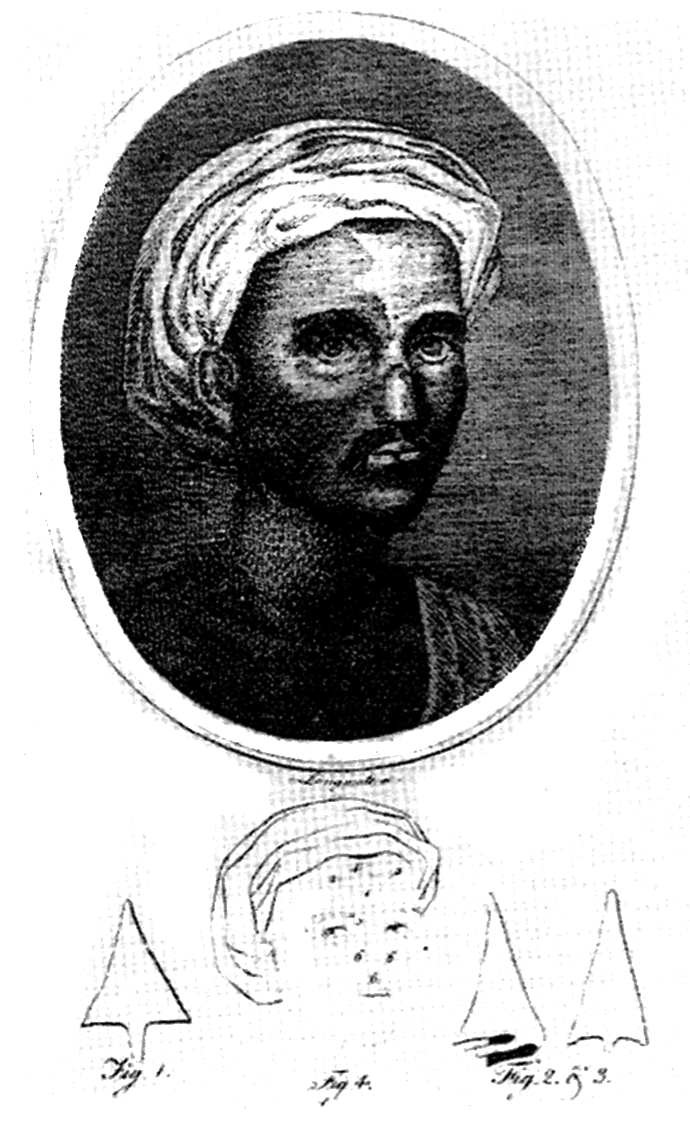

A prosthesis was evidently merely a makeshift, therefore attempts had always been made to correct the defect by means of reconstructive surgery. The method dating back furthest in time was, to current day knowledge, that of the Indian surgeons, even if it should not be forgotten that the first known description of repair of a loss of substance by means of sliding flaps was that of Aulo Cornelio Celso in the 1st Century (De Medicina VII, 9). The Indian surgeons used skin from the cheek and above all that of the forehead turned below, using always the same technique from the 1st to the 19th Century, as demonstrated by the findings of historical reports through the ages. A far as concerns the use of the Indian method, in the not too distant ages, articles by Lucas and by Carpue would appear to be particularly significant. Colley Lucas was an English Doctor who lived in Madras and who, in 1794, described the case of a Hindu, in Gentleman’s Magazine. The man, belonging to the British military forces, was taken prisoner by the Sultan Tippo Sahib during the campaign of 1792 and had had both his nose and hand chopped off. One year later, he was operated upon by a local surgeon who managed to reconstruct the nasal pyramid with excellent results from an aesthetic and functional viewpoint, employing the classic method which was described in detail by Lucas in the above-mentioned article (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Illustration from the article by Lucas which appeared in Gentleman’s Magazine, in October 1794, reporting on the results of the Indian method used in reconstruction of the nasal pyramid employing a folded over forehead flap (from Willemot, 1981 3)

By means of the Indian technique, which had been used also by other European surgeons, such as Jacques Lisfranc 2 3 10. John Carpue, in 1816, successfully reconstructed the nose of an English Officer, who had been mutilated by a sabre in the battle of Albuera in Spain (1810).

Celso’s method was also used again, in Europe by Michel Serre (1842) and by Johann Dieffenbach (1841), but, without doubt, that most used was the Italian procedure of Gaspare Tagliacozzi, in which skin from the arm was employed, the main supporter being Carl von Graefe from Berlin 3 13.

If surgical reconstruction of the nasal pyramid gave rise to controversy limited to the choice of the technique to be used, much greater contrasts arose regarding the possibility of attachment of a stump removed and directly reimplanted. Some, such as Lanfranco da Milano (13th Century), Guy de Chauliac (14th Century), Andrea Della Croce (16th Century), were convinced that a favourable result was absolutely impossible because in the detached part, the “vital spirits” would no longer be present, others such as, for example, Teodorico da Cervia (13th Century), Leonardo Fioravanti (16th Century), Fabritus Hildano (16th Century), held that it was possible provided reimplantation was performed within a short time after mutilation, while yet others, such as, Johann Yperman (XIII Century), Ambroise Paré (16th Century), Pierre Dionis (18th Century), were convinced that the implanted part would have been maintained alive only if not completely detached, but held in place by at least a small portion of tissue.

The literature devoted to the history of medicine is rich in examples, in this respect, and previously some particularly unique and curious examples, have been described herein. In fact, when I started searching for references on this topic it was, merely, a matter of curiosity, but as time passed by I was pleasantly surprised as a large number of reports emerged, often fascinating and little known, which I gradually managed to collect and which I found very gratifying, encouraging me to select a few that would be useful in the preparation of an article. In closing, if a phrase is to be added to the present report, a phrase that, in synthesis, describes how the nose, has been, throughout history, the part of the body most exposed to mutilation and how numerous causes may be responsible, all quite different one from the other, then probably the most appropriate, in this context, would have to be that of August Vidal de Cassis: “C’est la partie du corps qui a plus souffert de la haine, de la jalousie, de l’honneur, de la chasteté, de la justice” 14.

Pictures in the article are taken from J. Willemot et al. Naissance et développement de l’O.R.L. dans l’histoire de la médecine. Acta ORL Belgica 1982;35(Suppl. 2) and from W. Pirsig, J. Willemot. Ear, nose and throat in culture. Oostende: G. Schmidt; 2001.

In order to respect copyright regulations, every effort has been made by the Publisher to gain permission to print the figures reproduced in the present article, but this has not been possible. Eventual holders of the copyright are invited to contact Pacini Editore SpA in order that reference may be made to the holders of the afore-mentioned material in forthcoming issues of the journal.

References

- 1.Cabanés A. Les curiosités de la médicine. Paris: Maloine; 1900. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerrier Y, Mounier-Kuhn P. Histoire des maladies de l’oreille, du nez et de la gorge. Paris: Dacosta; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willemot J. Naissance et développement de l’ORL dans l’histoire de la médicine. Acta Otorhinolar Belg 1981;35(Suppl.2):273-5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fioravanti L. Il tesoro de la vita humana. Venice: Valgrisi; 1673. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperati G. I chirurghi empirici italiani e l’affermazione della rinoplastica nel XV secolo. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 1993;13:267-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirsig W, Willemot J. Ear, nose and throat in culture. Oostende: Schmidt; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Garengeot RJC. Traité des opérations de chirurgie. Paris: Brosson; 1720. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hildanus W. Fabricius. Observationum et curationum chirurgicarum centuriae. Frankfurt-Basel; 1606. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dionis P. Cours d’opérations de chirurgie. Paris: L. D’Oury; 1716. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weir N. Otolaryngology. An illustrated history. London: Butterworths; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cloqueth H. Osphrésiologie. Paris: Mequignon-Marvis; 1821. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parè A. Dix livres de la chirurgie. Paris: Le Royer; 1564. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeis F. Die Literature und Geschichte der plastischen Chirurgie. Dresden: 1862. Reprinted Bologna: Forni; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vidal de Cassis A. Traité de pathologie externe et de médicine opératoire. Paris: Smith; 1846, III. p. 590. [Google Scholar]