Abstract

Background

3% to 4% of the population suffers from chronic coronary artery disease (CAD). Primary care physicians, internists, cardiologists, and cardiac surgeons are involved in their long-term care. This article presents a complementary care pathway that integrates two apparently competing treatment options, aortocoronary bypass surgery (ACB) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Together with lifestyle changes and medical therapy, these treatments reduce morbidity and mortality and improve quality of life.

Methods

This article was written by cardiac surgeons and cardiologists on the basis of the current treatment guidelines for coronary artery disease, a selective review of the literature (randomized, controlled trials and registry data), and a process of interdisciplinary consensus building.

Results and conclusions

Lifestyle changes can reduce cardiovascular risk factors, improve quality of life, and lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. They provide additional benefit over and above medical therapy and/or revascularization procedures and should be strongly recommended to all patients. Revascularization is not indicated for patients who are asymptomatic on medical therapy or who have only a small area of myocardial ischemia. With either PCI or ACB, the symptoms of angina pectoris can be markedly improved, or even eliminated. Both of these revascularization procedures should be accompanied by optimized medical treatment. Revascularization is indicated when the area of myocardial ischemia is large, whether or not symptomatic angina is present. ACB is the treatment of choice for 3-vessel disease and/or left main stenosis. For all other constellations of coronary findings, ACB and PCI are equally good therapeutic options. The treating physician should take the patient’s expectations into account and present the short- and long-term benefits and drawbacks of each proposed treatment to the patient so that an informed decision can be made.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, chronic disease, cardiac surgery, bypass surgery, ischemia

Approximately 3% to 4% of the population suffers from chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) (1). The long-term care of these patients involves primary care physicians, internists, cardiologists, and cardiac surgeons. Up to a few years ago, chronic CAD, principally manifested by stable angina pectoris, was thought to be a steadily progressing process culminating in myocardial infarction. Now that the pathogenesis of the acute coronary syndrome has been clarified, however—with rupture or erosion of a vulnerable plaque as the triggering event—it seems that stable CAD and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are different manifestations of coronary atherosclerosis with differing prognoses. Thus, each requires its own treatment strategy: in ACS the most important measures are swift diagnosis and revascularization (2), while in stable CAD the choice has to be made between revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or aortocoronary bypass surgery) and exclusively medical treatment.

The goal of this review is to demonstrate how the apparently competing surgical options—aortocoronary bypass (ACB) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—can be sensibly integrated into a complementary treatment plan. Together with lifestyle modification and medical treatment, in this way the patients’ quality of life can be improved and morbidity and mortality lowered.

Methods

This review was performed jointly by cardiac surgeons and cardiologists. It is based on the current management guidelines for CAD, a review of the literature with continuous searching of the Medline database (PubMed) (randomized controlled trials and registry data), and a process of interdisciplinary consensus building.

The authors drew upon the German interdisciplinary National Disease Management Guideline "Chronische Koronare Herzkrankheit" (Chronic Coronary Artery Disease), an exemplary guideline that has achieved broad consensus among the various disciplines involved (3). It was decided not just to analyze the results of randomized controlled trials but to include the complementary data from large registries.

Results and discussion

Treatment goals

The targets of treatment of chronic CAD (box 1) are on one hand improvement of the prognosis, on the other an increased quality of life for the patients, with a minimum of procedural complications. All those participating in treatment should follow the guideline recommendations or base their actions on the best available evidence.

Box 1. Treatment goals—recommendations of the German National Disease Management Guideline "Chronic Coronary Artery Disease"*.

-

Improvement of patients’ quality of life

Avoidance of angina pectoris

Maintenance of exercise tolerance

Reduction of CAD-associated mental illness (depression, anxiety disorders)

-

Reduction of cardiovascular morbidity

Especially avoidance of myocardial infarction and the development of cardiac insufficiency

Reduction of disease-related mortality

* National Disease Management Guideline "Chronic Coronary Artery Disease" 2006 (3)

Lifestyle modification and medical treatment

The cornerstones of the treatment plan for stable CAD are on one hand healthy living (lifestyle modification) and on the other full exploitation of the medical treatment options (box 2). The results that can be achieved are comparable to those of PCI, and not only in patients with a lower coronary risk constellation (4) or in those more highly motivated to exercise (5). Also in patients with coronary three-vessel disease and proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (6, e1), medical conservative treatment matches primary revascularization by means of PCI for the criterion "mortality." Even for the goal "improvement in quality of life," the difference is only slight. However, both patient and physician face challenges if the "conservative" treatment goals (as in the COURAGE study) (box 2) (6) are to be achieved.

Box 2. Management of chronic CAD: lifestyle modifications and medical treatment.

a) Lifestyle modifications

a1) Give up smoking*1

a2) Physical activity for 15 to 60 min, 3 to 7 times each week at non-ischemic load level*1, or 5 times each week for 30 to 45 min*2

a3) Lose weight

Body mass index (BMI) 27 to 35 kg/m2: lose 5% to 10% within 6 months; BMI >35 kg/m2: lose more than 10% within 6 months*1

Initial BMI 25 to 27.5 kg/m2: reduction of BMI to <25 kg/m2; Initial BMI >27.5 kg/m2: reduction of BMI by 10%*2

a4) Mediterranean diet

consisting of a high proportion of fruit, vegetables, and roughage, olive oil; animal protein in the form of fish, if possible; moderate alcohol consumption; low proportion of saturated fatty acids*1

a5) In the case of diabetes mellitus: normoglycemia*1

(HbA1c<7.0%)*2

b) Medical treatment

b1) Aspirin for inhibition of thrombocyte aggregation

(75 to 325 mg/d),

in the case of intolerance, clopidogrel

b2) Treatment with a statin

Target LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL (<2.6 mmol/L)*1

or <85 mg/dL (<2.2 mmol/L)*2

b3) Regulation of blood pressure (BP)

Target BP <140/90 mm Hg (<130/80 mm Hg in diabetics)*1

or <130/85 mm Hg (<130/80 mm Hg in diabetics)*2

b4) Treatment with a beta blocker*1*2*3

Resting heart rate: target value 55 to 60/min*1*3.

In the case of beta blocker intolerance: ivabradine*3

*1 Recommendations of the National Disease Management Guideline "Chronic Coronary Artery Disease" (3); (http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/khk/nvl_khk)

*2 Treatment goals of the COURAGE study (e14)

*3 Recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology for the treatment of stable angina pectoris (e2); see also (e15)

Revascularization goal: elimination of myocardial ischemia

The indication for interventional (box 3) or surgical (box 4) coronary revascularization is usually determined on the basis of the morphology as revealed by angiography. However, revascularization yields convincing results primarily when management focuses not only on symptomatic reduction of angina but also on objective elimination of the ischemic zone (7). The latter can be demonstrated in a stress test by, for example, electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), myocardial scintigraphy, or positron emission tomography (PET).

Box 3. Interventional coronary revascularization: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

PTCA (balloon dilatation), first performed in patients by Andreas Grüntzig in 1977, enabled the dilatation of severely stenosed coronary vessels without surgery. In 1992 the ACME study compared PTCA (then still without stent implantation) with medical treatment in coronary single-vessel disease. A significant amelioration of symptoms and an increase in exercise tolerance were found in the patients treated with PTCA (23).

Routine application of techniques developed from PTCA/PCI, such as atherectomy, use of a cutting balloon, or laser angioplasty, has yielded results no better than those of classic balloon dilatation (24); nevertheless, these procedures may be justified in individual cases depending on the morphology of the stenosis.

-

Medical treatment versus PTCA/PCI: prognosis

Because of the equivalence of ACB and PCI in nondiabetic patients with coronary multi-vessel disease in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) (25) and the superiority of surgical revascularization over medical treatment in the CASS (22), it was concluded that PTCA/PCI was also superior to medical treatment in severe CAD with regard to prognosis. However, this has not been confirmed in ongoing studies (MASS-II and COURAGE) (e12, 6).

Stents: bare metal stents and drug-eluting stents

Routine implantation of stents has improved the clinical course after PTCA and is now standard in the treatment of stenoses both of native coronary arteries and of venous bypass vessels (recommendations and evidence level IA in the guidelines). Stents made of stainless steel (bare metal stents, BMS) induce a tissue reaction in the form of intimal hyperplasia. This is often excessive and eventually leads to an iatrogenic condition, "in-stent stenosis." Drug-eluting stents (DES) reduce the frequency of in-stent stenoses to a clinically significant degree by releasing antiproliferative substances, thus obviating the need for repeat revascularization. A total of 10 drugs have been tested in randomized DES studies, including actinomycin D, biolimus A9, dexamethasone, paclitaxel, and rapamycin. Around 30 000 patients have been included in randomized studies of DES; most of the investigations have been performed in patients with stable angina pectoris. DES reduce the re-stenosis rates significantly, but are associated with a slightly higher rate of late stent thromboses. Because of their antiproliferative mechanism of action, DES heal more slowly than uncoated BMS and therefore require more than the otherwise usual 4 weeks of dual inhibition of thrombocyte aggregation with aspirin and clopidogrel. The use of DES necessitates a course of at least 6 months’ dual platelet inhibition with aspirin and clopidogrel, possibly extended to a year or more if required, balancing the risk of a stent thrombosis against the danger of hemorrhage. DES should be implanted preferably in patients with increased risk of re-stenosis, i.e., those with stable CAD with symptomatic (angina pectoris, myocardial ischemia) coronary stenosis with vascular diameter ≤3 mm and/or stenosis length ≥15 mm, after successful reopening of an occluded coronary artery, and in BMS in-stent stenoses.

-

Surgery and dual antithrombocytic treatment after stent implantation

Life-threatening bleeding may occur on surgical intervention during dual antithrombocytic treatment! On the other hand, preoperative discontinuation of the dual antithrombocytic treatment is liable to result perioperatively in acute stent thromboses and frequently fatal myocardial infarctions!

Strategies to avoid perioperative stenoses (e16):

-

In all cases

Detailed information and training of all physicians involved (including dentists); detailed explanation to the patient (stent passport)

-

Can PCI or surgery be postponed?

If possible, avoid preoperative PCI

If PCI is required, then preferably without stent implantation

If stent implantation is essential, an uncoated stent is preferred

If possible, postpone surgery (6 weeks after BMS, ≥6 months after DES)

-

When surgery cannot be delayed

If possible, uninterrupted perioperative continuation of dual platelet inhibition

As an alternative, aspirin monotherapy: discontinue clopidogrel for a few days (in the hospital, with PCI staff on call), substitute a short-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist; recommence clopidogrel with an initial dose of 600 mg

PCI: preferentially use a short-acting antithrombin (bivalirudin)

-

Box 4. Coronary artery bypass surgery.

Surgical revascularization was introduced in 1968 in the form of the classic aortocoronary venous bypass (ACVB) (e10). The Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) compared medical treatment with surgical revascularization in randomized fashion. Retrospective review after 8 years (22) showed a survival advantage for surgery only in the subgroup of patients with ejection fraction reduced to 35% to 50%—half of whom suffered from coronary three-vessel disease (e11)—not in the total study group. Whether this survival advantage would persist on comparison with today’s considerably more effective medical treatment for cardiac insufficiency is dubious: The CASS was performed in the pre-ACE inhibitors era, and the administration of a beta blocker in cardiac insufficiency was still considered contraindicated. In contrast to the questionable survival advantage, all subgroups with bypass surgery showed a clear amelioration of the cardiac symptoms.

Modern technical concepts of bypass surgery permit durably successful treatment of CAD in practically any patient. Optimal management of the majority of patients is offered by the standard technique with left mammary artery bypass to the anterior wall and venous bypasses to the lateral and posterior wall. Particularly well suited for younger patients are approaches involving more extensive use of arteries, right up to complete arterial revascularization, with even better long-term prospects. The right mammary artery is employed preferentially, but the radial artery can also be used, often with sequential anastomoses. In the great majority of cases, the bypass is inserted with the patient in induced cardiac arrest on a heart-lung machine. However, bypass operations on the beating heart without the need for mechanical heart-lung perfusion are technically feasible and can achieve very good results for anterior wall revascularization (MIDCAB [minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass] and multiple-vessel anastomosis [OPCAB: off-pump coronary artery bypass]).

Although the mean annual mortality for coronary surgery in Germany (embracing reoperations and surgery for acute coronary syndrome, including all emergencies) is around 3%, in most centers the risk of death for a patient with a normal risk profile undergoing planned surgery is only 0.5% to 1.5%, even for left main stenoses. Conceptually the bypass begins in a relatively healthy segment of the vessel and thus effectively protects the patient from renewed symptoms related to the progression of the CAD.

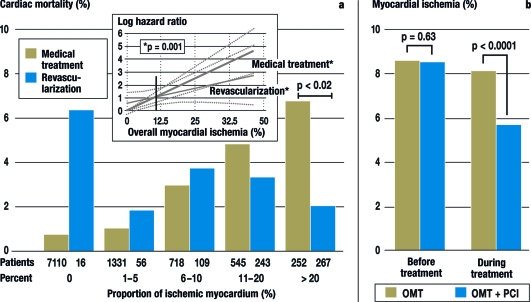

Revascularization by PCI and ACB is superior to solely medical treatment for moderate to severe myocardial ischemia, when more than 10% of the myocardium is ischemic, but revascularization has no advantage when less than 10% of the myocardium is involved (figure) (8). The greater the extent of myocardial ischemia in a patient with chronic CAD, the higher the risk of myocardial infarction or a fatal heart attack. Hence revascularization should be preferred in extensive myocardial ischemia, because it reduces the ischemia more effectively than the currently available medical treatment options. It remains to be shown whether new pharmacological approaches (ivabradine [e2], ranolazine, new antithrombotics) can improve the medical conservative treatment of ischemia.

Figure.

Cardiac mortality by extent of myocardial ischemia and type of treatment (medical or revascularization)

a) Cardiac-related mortality rate within 1.9 years in 10 367 patients with stable CAD and myocardial ischemia as quantified by stress scintigraphy (10). The patients in this study (10) either received exclusively medical treatment (n = 9956) or underwent additional revascularization (n = 671; aortocoronary bypass surgery [ACB] = 325, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] = 346). The figure shows the mortality rate in the two groups in relation to the extent of myocardial ischemia initially present. The inset depicts the relative risk of cardiac death for the two groups depending on the extent of myocardial ischemia, with the risk of death for 10% myocardial ischemia set at 1. If 10% or more of the myocardium is ischemic, revascularization is advantageous with regard to survival. Adapted from Hachamovitch et al. (8)

b) Reduction of myocardial ischemia by means of optimal medical treatment (OMT) or OMT+PCI in patients with chronic CAD (e18). In this subgroup of the COURAGE study, with 314 patients, the proportion of the myocardium affected by ischemia was determined by myocardial scintigraphy before and after 6 to 18 months of OMT (n=155) or OMT+PCI (n=159). The decrease in percentage of ischemic myocardium was greater with OMT+PCI than with OMT alone. The prognostic significance of the success achieved in the OMT+PCI group becomes apparent when one considers that in this predefined subgroup analysis of the COURAGE study higher residual myocardial ischemia led to a higher MACE (major adverse cardiovascular event) rate. Adapted from Shaw et al. (e18)

Today, the standard means of demonstrating myocardial ischemia is either by stress ECG or by imaging (echocardiography, scintigraphy, or MRI) under conditions of physical or pharmacological stress. Measurement of the fractional flow reserve (FFR) with a pressure wire (i.e., measurement of trans-stenotic intracoronary pressure gradient before and after maximal vessel dilation) permits estimation of the functional significance of a coronary stenosis (9) during cardiac catheterization.

Knowing the significance of myocardial ischemia, invasive coronary diagnosis is indicated when ischemia has been sufficiently demonstrated by noninvasive means and the patient would be in agreement with revascularization if extensive myocardial ischemia were found. In routine practice, however—at least in the USA—the demonstration of ischemia is frequently not performed (e3).

ACB or PCI? What do the guidelines say?

Whatever procedure is used to treat stable angina pectoris—conservative medical, PCI, ACB—the management must be oriented on the treatment goals (box 1). With an annual incidence of myocardial infarction of 3% to 3.5% and overall 5-year mortality of 8%, the treatment goals include not only reduction of disease-related mortality but also, above all, reduction of cardiovascular morbidity (major adverse cardiovascular events [MACE], e.g., re-PCI, re-ACB, cardiovascular related death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, hospitalization for cardiac insufficiency, stroke) and improvement of the patients’ quality of life.

Depending on the treatment goal, the treating physician’s discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of PCI and ACB (table 1) with his/her patient can lead to different conclusions.

Table 1. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and aortocoronary bypass surgery (ACB).

| Indication (see table 2) | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| PCI |

|

|

|

| ACB |

|

|

Compared with PCI:

|

The National Disease Management Guideline "Chronische Koronare Herzkrankheit" (Chronic Coronary Artery Disease) (www.versorgungsleitlinien.de) (3) states that PCI or ACB are indicated in patients in whom stable angina pectoris (CCS class III and IV) persists after medical treatment according to the guideline ("angina indication") or in whom noninvasive diagnostic measures have satisfactorily demonstrated ischemia ("ischemia indication"). The recommendations regarding revascularization are presented in table 2.

Table 2. Recommendations for revascularization treatment (from the German National Disease Management Guideline "Chronic Coronary Artery Disease" (3).

| Coronary artery disease with significant (≥50%) coronary left main stenosis | |

| ⇑ ⇑ | Surgical revascularization (ACB) should be performed if possible in the case of significant coronary left main stenosis. ACB is superior to PCI and conservative treatment in terms of survival, MACE, and quality of life. |

| ⇑ ⇑ | PCI is recommended as an alternative for inoperable patients and patients who refuse surgical revascularization after careful explanation. This holds for the treatment goals "improvement of prognosis" and "quality of life." |

| Coronary multi-vessel disease with severe proximal stenosis (≥70%) | |

| ⇑ ⇑ | Revascularization measures should be recommended in patients with multi-vessel disease because the quality of life can be raised and—according to expert opinion and registry data—the prognosis improved. |

| ⇑ ⇑ | Complete revascularization should be the goal in multi-vessel disease. |

| ⇑ ⇑ | In three-vessel disease (see legend) ACB is the primary and PCI the secondary procedure. |

| Coronary artery disease with proximal LAD stenosis (>70%) | |

| ⇑ | Regardless of their symptoms, patients with a proximal LAD stenosis (≥70%) should undergo revascularization. |

| Coronary single-vessel disease | |

| ⇑ ⇑ | All other patients (without LAD stenosis) with symptomatic single-vessel disease that cannot be adequately controlled by medical treatment should undergo a revascularization procedure (as a rule PCI) to ameliorate their angina. |

| Elderly patients (>75 years) with coronary artery disease | |

| ⇑ ⇑ | Elderly patients (>75 years) with pronounced persisting symptoms despite medical treatment should be recommended revascularization. |

| ⇑ ⇑ | In comparison with medical treatment PCI and ACB lead to a clear amelioration of the symptoms of CAD without causing an increase in mortality. They should also be recommended in elderly patients with pronounced persisting symptoms despite medical treatment. |

Corresponding to the National Disease Management Guideline "Chronic Coronary Artery Disease," the constellation is termed coronary three-vessel disease when proximal severe stenosis of over 70% is present in three of the great coronary vessels, i.e., both in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX) and in the right coronary artery, or their major branches (LAD: diagonal artery; LCX: left marginal artery).

The recommendations apply to the following clinical situation: diagnosis of chronic CAD with stable angina pectoris/angina equivalent, amenable to revascularization (independent of ventricular function) ⇑ ⇑= strongly recommended; ⇑ = recommended (3) ACB, aortocoronary bypass surgery; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CAD, coronary artery disease

Comparison of ACB and PCI—impact on cardiovascular mortality

Finding: coronary multi-vessel disease

ACB is the method of choice for coronary three-vessel disease (see the legend accompanying table 2), particularly in patients with restricted pump function.

The most recent meta-analysis, published in 2007 (10), embraced 23 studies and a total of 10 000 patients (only one study with a drug-eluting stent). It showed only a small difference in 5-year survival rate between ACB (90.7%) and PCI (89.7%). Procedural strokes were significantly more common after ACB (1.2%) than after PCI (0.6%). With regard to the treatment goal of freedom from angina pectoris after 5 years, ACB (84%) was more successful than PCI (79%) (p<0.001). The rate of repeat revascularization within 5 years was 46.1% after coronary angioplasty without a stent and 40.1% after stent implantation, but only 9.8% in patients treated with ACB (p<0.001). Patients with marked coronary findings seemed to have a lower risk of mortality with ACB, while PCI appeared more favorable in this respect for patients with less severe findings (10).

New York registry data on 17 000 patients with coronary multi-vessel disease compared the results of ACB and implantation of a drug-eluting stent (DES), thus complementing early data comparing ACB and a non-drug-coated ("bare metal") stent (11):

After risk adjustment, ACB patients had a 20% lower (hazard ratio [HR] 0.80) 18-month mortality (survival rate 94.0% vs. 92.7%, p=0.03). The combination of death and myocardial infarction was 25% lower (HR 0.75) and the rate of survival without myocardial infarction was higher in the ACB group (92.1%) than in the DES group (89.7%). More favorable results for ACB were also found in the subgroup of patients with coronary two-vessel disease (death: HR 0.71; survival rate 96.0% vs. 94.6%, p<0.003; death and myocardial infarction: HR 0.71; survival without myocardial infarction: 94.5% vs. 92.5%, p<0.0001). Moreover, ACB patients less often have to undergo repeat revascularization.

In summary, registry analyses show that even when a DES is implanted, ACB achieves a higher survival rate than treatment by PCI in three-vessel disease. Moreover, ACB patients less frequently require repeat revascularization and suffer less disease-related impairment of quality of life.

In patients with previous interventional treatment, it must be established in each individual case to what extent antithrombocytic or anticoagulation treatment should be continued right up to the time of operation. Recent findings indicate that PCI-pretreated patients with multi-vessel disease may have a higher surgical risk (e4), and this must be considered when choosing the primary strategy. In patients in whom a stent was implanted uncritically problems may be encountered finding a favorable site for a bypass anastomosis. In other words: extensive PCI treatments can eliminate surgical options.

Finding: left main stenosis

The superiority of ACB over medical treatment for left main stenosis has been demonstrated in subgroup analyses of large randomized studies, e.g., the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) (12). There is a lack of such studies, however, enabling comparison of ACB and PCI. Early observational studies of PCI treatment for left main stenosis showed that good acute success rates were accompanied by a high rate of severe complications; however, these studies included a high proportion of patients treated for acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, and/or multimorbidity. The results achieved with DES in elective patients with left main stenosis have been quite encouraging (e5), and recent registry studies (13, 14) based on a propensity score have also revealed only slight differences from ACB. Nevertheless, the recurrence rates remain high in bifurcation stenoses, and stent thromboses are still particularly dangerous.

In view of the available data, ACB is the primary treatment procedure for stenosis of the "unprotected" main stem of the left coronary artery (i.e., neither the LAD nor the LCX [left circumflex artery] is bypassed). PCI is reserved for individual cases in which the stenosis and vessel situation is favorable, e.g., collaterals, or in which surgery would be problematic.

Finding: coronary single-vessel disease with severe proximal LAD stenosis

Proximal LAD stenoses and their revascularization are of particular significance for the prognosis, because the area of the left ventricle supplied by the LAD is often larger than that supplied by the LCX and the right coronary artery together.

On the basis of this experience ACB and PCI (implantation of a bare metal stent) were compared in patients with isolated severe proximal LAD stenosis. In the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS) (15), the internal thoracic bypass was inserted conventionally, while in two other studies (16, 17) a minimally invasive technique was used to insert the internal thoracic bypass. The mortality was low overall, and the studies found no difference between ACB and PCI or between MIDCAB (minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass) and PCI.

Following surgical revascularization angina pectoris also occurs less frequently in single-vessel disease, so there is less need for repeat revascularization. Bypass surgery, preferably MIDCAB, is therefore the procedure of choice after unsuccessful PCI or re-stenosis of proximal LAD stenoses (e2).

Comparison of ACB and PCI—impact on angina pectoris and MACE rates

Both ACB and PCI reduce the symptoms of angina pectoris more effectively then medical treatment. Bypass surgery leads to very good medium- and long-term amelioration of angina pectoris. Renewed revascularization—repeated bypass surgery or PCI—is seldom necessary. In this regard surgical revascularization performs significantly better than PCI. This is due particularly to the problem of re-stenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA; i.e., only balloon dilatation, no stent implantation) or PCI. The introduction of uncoated and drug-coated stents reduced the necessity for repeat revascularization after 1 to 3 years from 30% to 15–20% and to 5–10%, respectively (e13). In the case of drug-coated stents, however, this came at the price of a slightly higher rate of late stent thromboses.

It is positive that in the case of an in-stent re-stenosis following PCI a single re-intervention usually suffices to achieve a stable long-term result (e6). All comparative studies convincingly demonstrate that the higher MACE rate of PTCA/PCI can be overwhelmingly attributed to the higher rate of re-intervention; the differences were at most slight for the other MACE criteria, e.g., death from cardiac causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or hospitalization for cardiac insufficiency.

Coronary revascularization in the elderly

In contrast to the widely held belief, revascularization—both interventional and surgical—represents a reasonable treatment option in older people (>75 years) with CAD (table 2). Surprisingly, registry studies showed higher 4-year survival rates in elderly patients treated with ACB or PCI than in those who received only medical treatment. The success of therapy was more pronounced for bypass surgery than for PCI (18). Above all, however, even at advanced age revascularization leads to a clear reduction in symptom severity without an accompanying increase in 1- and 4-year mortality (19, 20). On the other hand, in about 40% of elderly patients purely medical treatment does not control the symptoms adequately and revascularization becomes necessary (e7).

Of course, the decision regarding revascularization in the elderly will be influenced by the increased risk attendant upon intervention and the existence of any comorbidity. In the pre-stent era PTCA involved a 2 to 4 times greater periprocedural risk than in younger patients, but the difference has been greatly narrowed by stent implantation with optimized accompanying medical treatment. Comorbid conditions such as renal insufficiency or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease favor PCI over ACB.

Coronary revascularization in patients with chronic renal insufficiency and diabetes mellitus

Not only terminal renal insufficiency represents a hazard. Even moderate chronic renal insufficiency, with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 59 to 30 mL/min, raises the relative risk of morbidity and mortality for ACB (e8):

Perioperative mortality 1.55-fold

Stroke 1.47-fold

Prolonged ventilation 1.49-fold

Deep sternal infection 1.25-fold

Re-operation 1.3-fold

Longer hospital stay (>14 days) 1.54-fold

New dialysis requirement 4.65-fold.

PCI also involves an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with renal insufficiency (21), so that neither form of revascularization is currently recommended over the other. On the basis of these figures, great caution should be exercised when deciding whether revascularization is indicated, particularly if the principal aim is to ameliorate the symptoms.

Diabetes mellitus worsens the prognosis with regard to mortality and morbidity, both for surgical and for interventional revascularization. Subgroup analyses in a few studies (e.g. the BARI study) have found an advantage for surgical revascularization, but this effect has not been shown consistently in other studies. The FREEDOM Study can be expected to clarify this point (e9).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the president of the German Cardiac Society (DGK) and the German Society for Thoracic, Cardiac, and Vascular Surgery (DGTHG) for initiating this consensus paper. They thank Prof. Friedhelm Beyersdorf, Freiburg; Prof. Martin Borggrefe, Mannheim, Prof. Hans-Reiner Figulla, Jena, Prof. Hermann Reichenspurner, Hamburg, and Prof. Christian Hamm, Bad Nauheim, for fruitful discussions during preparation of the manuscript.

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Werdan has received financial support for research projects and honoraria from Servier for his work on the Advisory Board and as consultant. The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Bruckenberger E. 20. Herzbericht. www.herzbericht.de; www.bruckenberger.de. 2007.

- 2.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BÄK, KBV, AWMF. Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Chronische KHK. Köln: Deutscher Ärzteverlag; 2007/2008. www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/khk/pdf/nvl_khk_lang.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitt B, et al. Aggressive lipid-lowering therapy compared with angioplasty in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:70–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907083410202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambrecht R, et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2004;109:1371–1378. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121360.31954.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden WE, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies RF, et al. Asymptomatic cardiac ischemia pilot (ACIP) study two-year follow-up: outcomes of patients randomized to initial strategies of medical therapy versus revascularization. Circulation. 1997;95:2037–2043. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.8.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hachamovitch R, et al. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–2907. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonino PA, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bravata DM, et al. Systematic Review: The comparative effectiveness of percutaneous coronary interventions and coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:703–716. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannan EL, et al. Long-term outcomes of coronary-artery bypass grafting versus stent implantation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2174–2183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caracciolo EA, et al. Comparison of surgical and medical group survival in patients with left main equivalent coronary artery disease: long-term CASS experience. Circulation. 1995;91:2335–2344. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brener SJ, et al. Comparison of percutaneous versus surgical revascularization of severe unprotected left main coronary stenosis in matched patients. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seung KB, et al. Stents versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for left main coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1781–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hueb WA, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS): A prospective, randomized trial of medical therapy, balloon angioplasty, or bypass surgery for single proximal left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis. Circulation. 1999;100:II107–II113. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.suppl_2.ii-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeves BC, et al. A multi-centre randomised controlled trial of minimally invasive direct coronary bypass grafting versus percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with stenting for proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–43. doi: 10.3310/hta8160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiele H, Oettel S, Jacobs S, et al. Comparison of bare-metal stenting with minimally invasive bypass surgery for stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery: a 5-year follow-up. Circulation. 2005;112:3445–3450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham MM, et al. Survival after coronary revascularization in the elderly. Circulation. 2002;105:2378–2384. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016640.99114.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser C, et al. Risks and benefits of optimised medical and revascularisation therapy in elderly patients with angina - on-treatment analysis of the TIME trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfisterer M, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary artery disease with an invasive vs optimized medical treatment strategy: one-year results of the randomized TIME trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1117–1123. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Best PJ, et al. The impact of renal insufficiency on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killip T, Passamani E, Davis K. Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS): a randomized trial of coronary bypass surgery. Eight years follow-up and survival in patients with reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. 1985;72:102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parisi AF, Folland ED, Hartigan P. A comparison of angioplasty with medical therapy in the treatment of single-vessel coronary artery disease Veterans Affairs ACME Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:10–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201023260102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bittl JA, et al. Meta-Analysis of randomized trials of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty versus atherectomy, cutting balloon atherotomy, or laser angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger PB, et al. Survival following coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass surgery in anatomic subsets in which coronary artery bypass surgery improves survival compared with medical therapy: Results from the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1440–1449. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Hueb W, Lopes NH, Gersh BJ, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS II): a randomized controlled clinical trial of 3 therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1082–1089. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris; the experts of the European Society of Cardiology on the management of stable angina pectoris. Eur Heart J. 2006 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl001. http://www.escardio.org/guidelines-surveys/esc-guidelines/GuidelinesDocuments/guidelines-angina-FT.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, Malenka DJ, Vittinghoff E, Redberg RF. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Jama. 2008;300:1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Chocron S, Baillot R, Rouleau JL, et al. Impact of previous percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and/or stenting revascularization on outcomes after surgical revascularization: insights from the imagine study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:673–679. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Silvestri M, Barragan P, Sainsous J, et al. Unprotected left main coronary artery stenting: immediate and medium-term outcomes of 140 elective procedures. Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Kaehler J, Koester R, Billmann W, et al. 13-year follow-up of the German angioplasty bypass surgery investigation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2148–2153. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Pfisterer M the TIME Investigators. Long-term outcome in elderly patients with chronic angina managed invasively versus by optimized medical therapy: four-year follow-up of the randomized trial of invasive versus medical therapy in elderly patients (TIME) Circulation. 2004;110:1213–1228. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140983.69571.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Chirumamilla AP, Wilson MF, Wilding GE, Chandrasekhar R, Ashraf H. Outcome of renal insufficiency patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Cardiology. 2008;111:23–29. doi: 10.1159/000113423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Farkouh ME, Dangas G, Leon MB, et al. Design of the Future Revascularization Evaluation in patients with Diabetes mellitus: Optimal management of Multivessel disease (FREEDOM) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Favaloro RG. Saphenous vein autograft replacement of severe segmental coronary artery occlusion: operative technique. Ann Thorac Surg. 1968;5:334–339. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)66351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Passamani E, Davis KB, Gillespie MJ, Killip T. A randomized trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Survival of patients with a low ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1665–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506273122603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Hueb W, Soares PR, Gersh BJ, et al. The medicine, angioplasty, or surgery study (MASS-II): a randomized, controlled clinical trial of three therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease: one-year results. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1743–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Stettler C, Wandel S, Allemann S, et al. Outcomes associated with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: a collaborative network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:937–948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Design and rationale of the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive DruG Evaluation (COURAGE) trial Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program no 424. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1173–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Gohlke H, Kubler W, Mathes P, et al. Positionspapier zur primären Prävention kardiovaskulärer Erkrankungen. Z Kardiol. 2005;94(Suppl 3):III/113–III/115. doi: 10.1007/s00392-005-1316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Bonzel T, Erbel R, Hamm CW, et al. Leitlinie für perkutane Koronarinterventionen (PCI) Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:513–547. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0697-y. http://leitlinien.dgk.org/images/pdf/leitlinien_volltext/2008-08_pci.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Silber S, Borggrefe M, Böhm M, et al. Positionspapier der DGK zur Sicherheit und Wirksamkeit von Medikamente freisetzenden Stents (DES) Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:548–563. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0703-4. http://leitlinien.dgk.org/images/pdf/leitlinien_volltext/2008-09_des.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Shaw, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden. Results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]