Abstract

Background

Rickettsioses are diseases caused by rickettsiae, obligate intracellular bacteria that are transmitted by arthropods to humans. They cause various types of spotted fever and typhus.

Methods

A review of the literature is presented along with the authors’ own findings.

Results

Six indigenous species of rickettsiae have been found in Germany to date, five of which have been described as human pathogens in other countries. Rickettsia slovaca causes tick-borne lymphadenitis (TIBOLA). Rickettsia helvetica is a known pathogen of nonspecific fever; its role in endocarditis is still under investigation. Rickettsia felis causes so-called flea-borne spotted fever. Rickettsia monacensis and Rickettsia massiliae were recently shown to cause the classical form of tick-borne spotted fever. The sixth indigenous species in Germany, Rickettsia sp. RpA4, has not yet been associated with any human disease. The most important rickettsioses imported to Germany by travelers are African tick bite fever and Mediterranean spotted fever.

Conclusions

Modern molecular biological techniques have enabled the detection of a number of rickettsial species in Germany. The medical importance of these illnesses in Germany remains to be determined. In travel medicine, imported rickettsioses play a role that should not be underestimated.

Keywords: rickettsiosis, molecular biology, parasitosis, tick bite, head lice

Since mankind has existed, fleas and lice have been its permanent companions. In addition to the small volume of blood sucked and the allergic pruritus, these ectoparasites are important transmitters of communicable diseases. Fleas are well known for transmitting the plague. Lice transmit epidemic typhus, an infectious disease that is little known nowadays. However, this rickettsiosis (named after the causative strain) is of considerable historical importance and has probably helped decide the outcome of more wars than weapons have. Recent studies have shown that nucleic acids of Rickettsia (R.) prowazekii, the causative agent of spotted fever, was confirmed in 1 in 3 soldiers in Napoleon’s French army during his Russian campaign (Raoult, personal communication, 2006). Several new forms of spotted fever (rickettsioses) have been identified as causative agents of infection by molecular biological methods. The authors present an overview of current developments in the field of rickettsioses and their medical importance in Germany. Additionally, we performed a selective literature search on PubMed, using the search terms "Rickettsia," "Rickettsia species," or "Rickettsiosis," each in combination with the term "Germany," "travel," or "imported" and evaluated publications from 1960 to 2008.

Causative agent

Rickettsiae are gram negative bacteria with an exclusively intracellular replication cycle. They were named after Howard Ricketts, the American microbiologist who first described Rickettsiae as causative agents of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in 1906 (1). The organisms—long described as "large viruses"—were classified as bacteria, together with ehrlichiae and anaplasmae, only once cell biological and molecular biological procedures had become available (2).

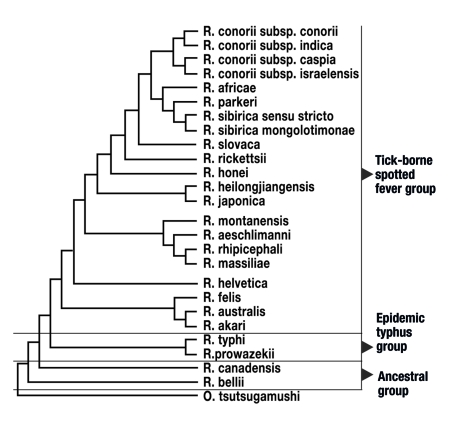

Serologically and molecularbiologically, Rickettsiae are categorized into three large groups. The group of tick-borne Rickettsiae (tick-borne spotted fever group), with more than 20 different species, the epidemic typhus group with 2 species (R. prowazekii, R. typhi) and the so-called group of ancestral Rickettsiae (R. Canadensis and R. bellii) (figure 1). All rickettsial species known thus far are transmitted by vectors in the natural environment and are capable of infecting humans. Vectors include ticks, fleas, lice, and mites (table 1).

Figure 1.

Relationships of the different humanopathogenic rickettsial species.

R = Rickettsia; subsp = subspecies

Table 1. Humanopathogenic rickettsioses with transmitting agents and geographical spread.

| Rickettsial species | Disease | Transmitting agent | Spread/distribution |

| R. prowazekii | Epidemic typhus | Clothes lice | Africa, Asia, Central and South America |

| R. typhi | Endemic typhus | Fleas | Worldwide |

| R. africae | African tick bite fever | Ticks | Sub-Saharan Africa, Caribbean |

| R. helvetica | Uneruptive tick bite fever | Ticks | Eurasia |

| R. marmionii | Australian spotted fever | Ticks | Australia |

| R. felis | Flea-borne spotted fever | Fleas | Presumed worldwide |

| R. heilongjiangensis | Far East tick-borne spotted fever | Ticks | Far East of Russia, Northern China |

| R. honei | Flinders Island tick bite fever; Thailand tick bite fever | Ticks | Australia, Thailand |

| R. sibirica subsp. mongolotimonae | Tick-borne lymphangitis | Ticks | Southern Europe, Asia, Africa |

| R. parkeri | Macular fever | Ticks | South America, North America |

| R. conorii | Mediterranean spotted fever | Ticks | Mediterranean, Middle East, India |

| R. sibirica | Siberian tick typhus | Ticks | Russia, China, Mongolia |

| R. japonica | Japanese spotted fever | Ticks | Japan |

| R. australis | Queensland tick typhus | Ticks | Australia, Tasmania |

| R. monacensis | Tick bite fever | Ticks | Europe |

| R. massiliae | Tick bite fever | Ticks | Europe |

| R. rickettsii | Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Ticks | North America and South America |

| R. slovaca | TIBOLA (tick-borne lymphadenitis) | Ticks | Eurasia |

| R. aeschlimannii | Tick bite fever | Ticks | Africa |

| R. akari | Rickettsialpox | Mites | Presumed worldwide |

R. = Rickettsia; subsp. = subspecies

Rickettsioses in humans

Rickettsial species are of huge medical importance in history and the present, as the causative agents of different forms of spotted fever. Epidemic typhus, which is transmitted by lice, has an important role in history—it was often among the factors that determined the outcome of wars. In recent years, an intensified search for new rickettsial species found several new species that were associated with new pathologies in some cases. This means that rickettsioses range among the "emerging" infections. At least 11 new rickettsioses in humans were discovered between 1985 and 2004 (table 2). In the meantime, tick-borne rickettsial species have been confirmed as having pathogenic potential in humans.

Table 2.

| Known humanopathogenic rickettsial species to 1984 | Humanopathogenic rickettsial species newly discovered between 1985 and 2004 |

| R. conorii | R. japonica |

| R. conorii subsp. israelensis | R. conorii subsp. caspia |

| R. sibirica | R. africae |

| R. australis | R. honei |

| R. prowazekii | R. sibirica subsp. mongolotimonae |

| R. typhi | R. slovaca |

| R. rickettsii | R. heilongjiangensis |

| R. akari | R. aeschlimanii |

| R. parkeri | |

| R. massiliae | |

| R. marmionii | |

| R. felis |

R = Rickettsia; subsp = subspecies

Indigenous rickettsial species and rickettsioses in Germany

Only few data are currently available with respect to the occurrence and prevalence of tick-borne Rickettsiae. This is partly because rickettsial species are difficult to detect in ticks as well as in patients. The first confirmation of a Rickettsia type in Germany since the 1960s came from 1977. Back then, R. slovaca was identified in ticks of the genus Dermacentor (3). In the same year, an antibody prevalence of 1.9% was confirmed in a German population using the complement fixation text (4). Up to 2002, only individual cases of spotted fever were reported that had been imported by tourists (5, 6). In 2002, a previously unknown rickettsial species from the tick-borne spotted fever group was identified in Munich (R. monacensis) (7). In the same year, an indigenous clinical case of fleaborne spotted fever (R. felis) from the Düsseldorf region was published (8).

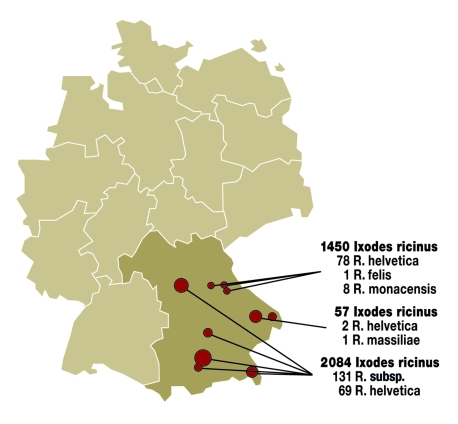

The most comprehensive molecular biological investigation to date, of 3500 ticks of the Ixodes ricinus type from different regions in Germany’s south, found 5 different rickettsial species in these ticks (figure 2). Table 3 summarizes the results.

Figure 2.

Results of molecular biological investigation of Ixodes ricinus for rickettsial species in Bavaria. R = Rickettsia; subsp. = subspecies

Table 3. Known prevalence of ticks in different regions of Germany*.

| Rickettsial species | Transmitting tick species | Penetration among German ticks | Occurrence | Disease | Source (literature) |

| R. helvetica | Ixodes ricinus | 3.5–6.2% | Southern Germany | Feverish infection without rash ("summer flu"), endocarditis | Authors’ own findings (9, 10) |

| R. felis | Ixodes ricinus | 0.4% | Northeastern Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia | Flea-borne spotted fever (feverish infection with maculo-papular exanthema and constitutional symptoms) | Authors’ own findings |

| R. massiliae | Ixodes ricinus | 1.7% | Eastern Bavaria and constitutional | Flea-borne spotted fever (feverish infection with maculo-papular exanthema symptoms) | Authors’ own findings |

| R. monacensis | Ixodes ricinus | 0.6% | Northeastern Bavaria, southern Bavaria | Flea-borne spotted fever (feverish infection with maculo-papular exanthema and constitutional symptoms) | Authors’ own findings (7) |

| R. sp. RpA4 | Dermacentor reticulatus | 21% | Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Brandenburg, Bavaria | Thus far, pathogenicity in humans has not been confirmed | (11) |

| R. slovaca | Dermacentor marginatus | No data | Hesse | TIBOLA (tickborne lymphadenitis) (feverish infection with swollen lymph nodes, no rash, localized alopecia) | (3) |

R = Rickettsia; sp = species; *According to cited literature and authors’ own findings (9)

These results, combined with the earlier confirmation of R. slovaca, have shown that at least 6 Rickettsia species occur in ticks in Germany. Five of the 6 cause disease in humans (table 3). The pathogenic potential of R. sp. RpA4 remains unclear to date. A study from Baden-Württemberg showed IgM titers or a significant rise in IgG titers to Rickettsiae of the tick-borne spotted fever group in some 5% of persons who developed a fever after receiving a tick bite (Dobler et al., unpublished results). The importance of R. helvetica as a cause of endocarditis remains unclear (12).

R. felis is the causative agent of the so-called flea spotted fever, a general infection accompanied by a raised temperature and a more or less pronounced measles-like rash. Individual case reports exist from North Rhine-Westphalia and Baden-Württemberg (Kimmig, personal communication, 2008). R. massiliae and R. monacensis have thus far not been confirmed in patients in Germany, but they have been diagnosed in other countries.

No current data are available on how common R. slovaca is in ticks in Germany, which was confirmed in 1977. This rickettsial species seems to be associated with ticks of the Dermacentor species. However, results from studies are lacking. The increasing spread of Dermacentor reticulatus (marsh tick or ornate cow tick) may, however, lead to an increased spread and transmission of this species. R. slovaca was identified as the causative agent of tick-borne lymphadenitis (TIBOLA). This general infection is accompanied by a raised temperature but, in contrast to other spotted fevers, it does not feature a rash. Lymphadenitis develops in the area of the bite. Because these ticks often suck blood on the hairy scalp, localized alopecia in patients has been reported in some cases.

Imported rickettsioses

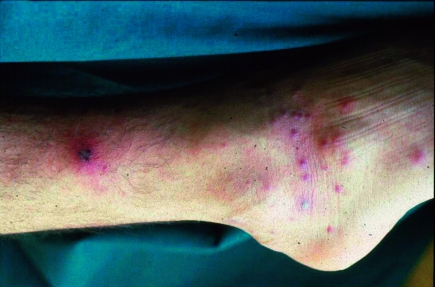

Individual case reports or summaries highlight the importance of cases of rickettsioses imported by tourists (table 4). These can be distinguished in some cases by the presence of an eschar and by the type of rash. Prospective studies of the frequency and medical importance of rickettsioses in travelers are lacking. The literature contains mainly cases of Mediterranean spotted fever (R. conorii) and African tick bite fever (R. africae). Mediterranean spotted fever is a severe illness characterized by a high temperature, severe muscular and articular pains, fatigue, and exhaustion. Patients with underlying disease (for example, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, alcoholism, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, or chronic renal disorders) have a notably higher case fatality rate. Delayed or inadequate treatment can also lead to more severe clinical courses and an increase in the number of deaths. The second most common rickettsiosis described in travelers is African tick bite fever, caused by R. africae. Several national parks in South Africa and Zimbabwe, including the Krüger National Park, are regarded as highly endemic areas. Travelers brush from the grass Amblyomma ticks, which seek hosts very aggressively (figure 3). The disease course is similar to Mediterranean spotted fever, but often notably milder (figure 4). Thus far, no deaths due to R. africae have been described.

Table 4. Importance of imported rickettsioses in travel medicine.

| Rickettsiosis | Known area of spread | Frequency of rash and type of rash | Eschar | Prevalence in travelers | Fatality rate | Literature |

| Mediterranean spotted fever | Mediterranean, Africa, central Asia,India | >90%, maculopapular, non-itching | Present primarily as individual eschars | >50 cases in Germany | 2.5–10% | 5, Löscher: personal communication |

| African tick bite fever | Sub-Saharan Africa, Caribbean | 100%, vesicular | Present primarily as multiple eschars | >50 cases inGermany | None | 16, Authors’ own data |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | North America, South America | >90%,maculopapular, pruritus in about half of cases | Rare | 1 case in Switzerland | 15–30% | 15 |

| Murine typhus | Worldwide | Ca 50%, macular | Not present | > 50 cases worldwide | <5% | 16 |

| Epidemic typhus | Africa, South America | Ca 50%, macular | Not present | Individual cases | 30% | 17, 19 |

| Siberian tick typhus | Northern Asia | 100%, macular | Mostly present | Single case | <1% | 16 |

| Queensland tick typhus | Australia | 100%, vesicular | Mostly present | Single case | <5% | 16 |

Figure 3.

Typical multiple eschars in African tick bite fever (with permission from Professor Dr Löscher, Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, University of Munich)

Figure 4.

Eschar and maculopapular rash in Mediterranean spotted fever (with permission from Professor Dr Löscher, Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, University of Munich)

A study at the Bundeswehr (Germany’s military forces) Institute of Microbiology of 164 travelers serologically confirmed acute infection with Rickettsiae of the tick-borne spotted fever group in 8 patients (4.9%) who developed feverish infections after returning from the tropics. In 16 patients (9.8%), IgG antibodies to Rickettsiae of the tick-borne spotted fever group provided a serological indication of previous infection with those particular rickettsial species (Dobler et al., unpublished results). After malaria, rickettsioses are the second most common cause of feverish infections in European tourists (Raoult, personal communication, 2005).

Other rickettsioses that are sporadically diagnosed in tourists are Rocky Mountain spotted fever, murine typhus (16), and louseborne spotted fever (table 4). An early diagnosis in suspected Rocky Mountain spotted fever is of crucial importance because a delay in diagnosis and inadequate treatment can raise case fatality to 30%. Murine typhus (R. typhi), which is usually transmitted by fleas, is one of the most common rickettsioses acquired while traveling (16). It often presents as an undifferentiated feverish infection and most probably affects more travelers than hitherto assumed but remains undiagnosed. Examination of tourists who had returned from the tropics and developed a feverish infection found serological indications of acute infection with murine typhus in 2 patients (1.2%). In 6 patients (3.7%), IgG antibodies were confirmed, which indicates previous infection (Dobler et al., unpublished results).

The feared louseborne spotted fever or epidemic typhus (R. prowazekii) has occurred in recent years only in a few cases in helpers in humanitarian campaigns (17). A case of louseborne spotted fever was diagnosed in a Frenchman traveling to Algeria (18). Louse-borne spotted fever is the only rickettsiosis that is known to have the potential for chronic infection and reactivation with fever after an interval of years (so-called Brill-Zinsser disease). These forms of spotted fever occur only rarely and affect patients who had spotted fever during the war years. In unfavorable hygienic settings, such chronically infected patients may infect lice when they undergo an episode of reactivation and thus initiate a new outbreak of infection. This reactivated form may be diagnosed in Germany in individual cases in members of the generation who fought in the war.

Further to these rickettsioses, individual cases of Siberian tick typhus (R. sibirica) have been noted in persons with professional exposure, and one case of severe Queensland tick typhus (Australian spotted fever, R. australis) in a traveler to Australia has been reported (table 4).

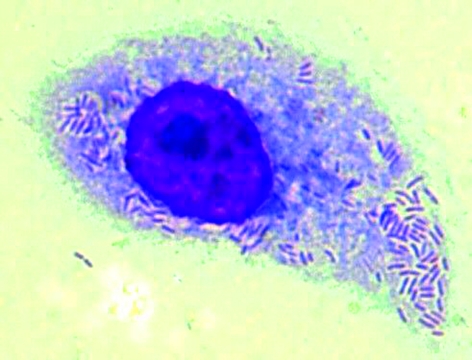

Diagnosis

Rickettsiae can be grown in different cell cultures (Vero cells), in chicken egg embryos or in animal experiments (guinea pigs’ testicles). The culture is difficult, however; it takes a long time and is therefore the preserve of specialist laboratories. Using the so-called shell vial technique (a method that uses small cell culture pipes and centrifugation of the clinical material) improves the culture rates compared with traditional methods (19). In rickettsioses of the tick-borne spotted fever group (African tick bite fever, Mediterranean spotted fever), cultures from biopsy material (eschar) hold the greatest promise. Blood is notably less suitable for confirming acute rickettsiosis. The specimens (biopsy materials, whole blood or serum, lice, fleas, ticks) need to be processed within 24 hours, preferably without being frozen and unfrozen. Even storage at minus 70 degrees Celsius impairs the culture rate substantially. The growth of Rickettsiae in the cell culture can be confirmed by using immunofluorescence, by using Gimenez or Romanowski staining (figure 5) or by real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The isolated Rickettsia type is usually identified by using molecular biological procedures. The sensitivity of the isolation depends on the time at which the material was sampled. In the initial days of illness it can reach up to 60%, whereas once antibodies appear it tends to fall to less than 10% (20).

Figure 5.

Rickettsia africae (isolate in L929 cells), Romanowski stain

PCR has become the established quick and preferred method for confirming Rickettsiae in clinical and biological materials. Biopsies (exanthema specimens) and peripheral leukocytes can be used. To confirm rickettsial species in blood by using PCR, EDTA or citrate blood is required. The sensitivity of PCR to confirm Rickettsiae in clinical materials is reported to reach up to 70% (20). Genus specific PCR methods are different from species specific PCR methods (21). The former capture all Rickettsiae but do not differentiate between individual species, whereas species specific PCR methods have become available for R prowazekii and other common species (R. conorii, R. rickettsii, R. typhi, R. slovaca, R. helvetica) (21). A clear distinction between the individual Rickettsia species that are genetically closely related is often made possible only by sequence analysis of certain gene regions. In the meantime, type specific and genus specific (among others, for R. prowazekii) real time PCR methods have become established (21). At the Bundeswehr Institute for Microbiology, a PCR-DNA hybridization test has been developed for rapid typing of humanopathogenic Rickettsiae (22).

Serological tests for the diagnosis of spotted fever infection are promising from the second week of illness. Close antigenic relatedness with pronounced cross reactivity exists within the two members of the epidemic typhus group (R. prowazekii, R. typhi) as well as within the members of the tick-borne spotted fever group. Because of its high sensitivity (>97%) and specificity (>99%), immunofluorescence has replaced the historical Weil-Felix reaction (cross reactivity with certain Proteus vulgaris strains) as the standard procedure (23). Commercial ELISA tests have not yielded convincing results so far, owing to low sensitivity and specificity (Dobler et al., unpublished results). To differentiate the antibodies between individual members of a spotted fever group, Western blot tests and preabsorption of antibodies need to be used, which are currently available only at very few laboratories worldwide.

Differential diagnosis

Other infectious disease may resemble and take similar clinical courses as spotted fever. The most important differential diagnoses include sepsis (especially meningococcal sepsis), typhoid fever, bacterial meningitis, stage II syphilis, leptospirosis, louseborne relapsing fever, mononucleosis, tularemia, plague, anthrax, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and exanthematous infections.

Treatment

The treatment for all forms of rickettsioses is doxycycline at a dosage of 2×100 mg/day p.o. (children >8 years 2 mg/kg body weight) for 7 to 10 days (evidence level I). If doxycycline is contraindicated, ciprofloxacin (2×750 mg) can be used instead, as sufficient experience has been gained in the treatment of rickettsioses (evidence level IIa). In pregnant women and children under 8 years of age, whose disease course is mild, macrolides may be administered (clarithromycin, azithromycin) (evidence level IIa) (24). However, experience with these antibiotics is limited. Except in pregnant or breastfeeding women, treatment with chloramphenicol is an option, if less risky antibiotics are ineffective or contraindicated (evidence level IIa). Rifampicin, which had been used in the past in children with spotted fever, should be used only if the Rickettsia type is known to be susceptible to the drug. Of the tick-borne spotted fever group, R. massiliae and R. aeschlimannii are resistant to rifampicin (25). Several treatment failures in Portugal have been described (25).

Prophylaxis

During the second world war, a vaccine against the causative agent of epidemic typhus (R. prowazekii) was developed. The manufacture ceased, however, because of the decreasing number of cases. Other vaccines are currently not available. The only way to avoid transmission of rickettsioses is to prevent exposure, in Germany particularly exposure to ticks. Accordingly, protection from ectoparasites should be made a priority during stays abroad. Chemoprophylaxis with doxycycline is an option, but this seems appropriate only in exceptional cases, when the exposure risk is high, for example, in the context of humanitarian campaigns.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr Birte Twisselmann.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Ricketts H. The transmission of Rocky Mountain spotted fever by the bite of the wood-tick (Dermacentor occidentalis) JAMA. 1906;47 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:719–756. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehácek J, Liebisch A, Urvölgyi J, Kovácová E. Rickettsiae of the spotted fever isolated from Dermacentor marginatus ticks in South Germany. Zentralbl Bakteriol (Orig A) 1977;239:275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmatz HD, Schmatz S, Krauss H, Weber A, Brunner H. Seroepidemiologische Untersuchungen zur Prävalenz von Rickettsien-Antikörpern beim Menschen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Immun Infekt. 1977;5:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jelinek T, Löscher T. Clinical features and epidemiology of tick typhus in travelers. J Travel Med. 2001;8:57–59. doi: 10.2310/7060.2001.24485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marschang A, Nothdurft HD, Kumlien S, von Sonnenburg F. Imported rickettsioses in German travelers. Infection. 1995;23:94–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01833873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simser JA, Palmer AT, Fingerle V, Wilske B, Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG. Rickettsia monacensis sp. nov., a spotted fever group Rickettsia, from ticks (Ixodes ricinus) collected in a European city park. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4559–4566. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4559-4566.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richter J, Fournier PE, Petridou J, Häussinger D, Raoult D. Rickettsia felis infection acquired in Europe and documented by polymerase chain reaction. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:207–208. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wölfel R, Terzioglu R, Kiessling J, et al. Rickettsia spp. in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Bavaria, Germany. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:509–511. doi: 10.1196/annals.1374.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartelt K, Oehme R, Hernning F, Brockmann SO, Hassler D, Kimmig P. Pathogens and symbionts in ticks: prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Ehrlichia sp)., Wolbachia sp., Rickettsia sp. and Babesia sp. in Southern Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293(37):86–92. doi: 10.1016/s1433-1128(04)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobler G, Essbauer S, Wölfel R. Isolation and preliminary characterization of Rickettsia monacensis in South-Eastern Germany. Clin Infect Microbiol (in press) doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson K, Lindquist O, Pahlson C. Association of Rickettsia helvetica with chronic perimyocarditis in sudden cardiac death. Lancet. 1999;354:1169–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitale G, Mansueto S, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Rickettsia massiliae: first isolation from the blood of a patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:174–175. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jado I, Oteo JA, Aldamiz M, et al. Rickettsia monacensis and human disease, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1405–1407. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.060186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balestra GM, Nüesch R. Eine Urlaubsreise-Erinnerung: Rocky Mountain Fleckfieber. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 2005;94:1869–1870. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensenius M, Fournier P-E, Raoult D. Rickettsioses in travellers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/425365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanetti G, Francioli P, Tagan D, Paddock CD, Zaki SR. Imported epidemic typhus. Lancet. 1998;352 doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)61487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niang M, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Epidemic typhus imported from Algeria. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:716–718. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vestris G, Rolain JM, Fournier PE, et al. Seven years’ experience of isolation of Rickettsia spp. from clinical specimens using the shell vial cell culture assay. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;990:371–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.La Scola B, Raoult D. Diagnosis of Mediterranean spotted fever by cultivation of Rickettsia conorii from blood and skin samples using the centrifugation-shell vial technique and the detection of R. conorii in circulating endothelial cells: a 6-year follow-up. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2723–2727. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2722-2727.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fournier PE, Raoult D. Suicide PCR on skin biopsy specimens for diagnosis of rickettsioses. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3428–3434. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3428-3434.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wölfel R, Essbauer S, Dobler G. Concepts of modern rickettsial diagnosis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298:368–374. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newhouse VF, Shepard CC, Redus MD, Tsianabos T, McDade JE. A comparison of the complement fixation, indirect fluorescent antibody, and microagglutination tests for the serological diagnosis of rickettsial diseases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:387–395. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cascio A, Colomba C, Antinori S, Paterson DL, Titone L. Clarithromycin versus azithromycin in the treatment of Mediterranean spotted fever in children: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:154–158. doi: 10.1086/338068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bella F, Espejo E, Uriz S, Serrano JA, Alegre MD, Tort J. Randomized trial of 5-day rifampin versus 1-day doxycycline therapy for Mediterranean spotted fever. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:433–434. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]