Abstract

Background

Severe obesity is reaching epidemic proportions throughout the world, including Canada. The only permanent treatment of severe or morbid obesity is bariatric surgery. Access to bariatric surgery is very limited in Canada. We sought to collect accurate data on waiting times for the procedure.

Methods

We carried out a survey of members of the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons and performed a more detailed analysis within Quebec and at one Canadian bariatric surgery centre where a prospectively collected bariatric surgery registry has been maintained since 1983.

Results

The survey response rate was 85%. All centres determined whether patients were eligible for bariatric surgery based on the National Institutes of Health criteria. Patients entered the queue as “office contacts” and moved through the queue, with the exit point being completion of the procedure. In 2007, a total of 6783 patients were waiting for bariatric surgery and 1313 procedures were performed in Canada. Assuming these trends are maintained, the calculated average waiting time for bariatric surgery in Canada is just over 5 years (6783/1313). The Fraser Institute and the Wait Times Alliance benchmarks for reasonable surgical waiting times vary from 8 weeks for cancer surgery to 18 months for cosmetic surgery. At one Canadian centre, 12 patients died while waiting for bariatric surgery.

Conclusion

The waiting times for bariatric surgery are the longest of any surgically treated condition. Given the significant reduction in the relative risk of death with bariatric surgery (40%–89% depending on the study), the current waiting times for the procedure in Canada are unacceptable.

Abstract

Contexte

L’obésité grave atteint des proportions épidémiques un peu partout dans le monde, y compris au Canada. La chirurgie bariatrique est le seul traitement permanent contre l’obésité grave ou morbide. L’accès à la chirurgie bariatrique est très limité au Canada. Nous avons cherché à recueillir des données exactes sur les temps d’attente pour cette intervention.

Méthodes

Nous avons réalisé un sondage auprès des membres de l’Association canadienne des médecins et chirurgiens bariatriques et procédé à une analyse plus détaillée au Québec et à un centre canadien de chirurgie bariatrique qui tient depuis 1983 un registre bariatrique établi prospectivement.

Résultats

Le taux de réponse au sondage a atteint 85 %. Tous les centres ont déterminé l’admissibilité des patients à une chirurgie bariatrique en fonction des critères des National Institutes of Health. Les patients sont entrés dans la file d’attente au moment où ils ont communiqué avec le bureau pour la première fois et y ont évolué jusqu’à la sortie, soit l’achèvement de l’intervention. En 2007, 6783 patients au total attendaient une chirurgie bariatrique et on a pratiqué 1313 interventions au Canada. Si l’on suppose que ces tendances se maintiennent, la moyenne calculée des temps d’attente en chirurgie bariatrique au Canada dépasse un peu 5 ans (6783/1313). Les points de repère de l’Institut Fraser et de l’Alliance sur les temps d’attente en ce qui concerne des temps d’attente raisonnables en chirurgie vont de 8 semaines dans le cas du cancer à 18 mois dans celui de la chirurgie esthétique. Dans un centre canadien, 12 patients sont morts en attente de chirurgie bariatrique.

Conclusion

Les temps d’attente en chirurgie bariatrique sont les plus longs parmi tous les problèmes traités par la chirurgie. Comme la chirurgie bariatrique réduit considérablement le risque relatif de décès (de 40 % à 89 %, selon les études), les temps d’attente actuels pour cette intervention au Canada sont inacceptables.

Obesity is now recognized as a chronic disease with multiple associated disorders.1 According to the World Health Organization, obesity is reaching epidemic proportions with more than 1 billion adults who are overweight, 300 million who have class I or II obesity and 30 million who have class III or morbid obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 kg/m2.2,3 Canada is no exception to this epidemic, as most of the Canadian population is overweight or obese,4 and 2% of men and 4% of women (about 900 000 people) are morbidly obese.5 Obesity-related death rates are at least on par with deaths related to smoking, with some authors believing that obesity is now the number one killer in North America.6

The nonsurgical treatment of severe obesity is a lifelong struggle with high recidivism.7 Although no one disputes the ability of morbidly obese patients to lose weight,8 the challenge is to maintain weight loss in the long term.9–11 Such weight-loss maintenance is critical to achieving the beneficial effects of reduced weight. Bariatric surgery is the only treatment modality that produces substantial, sustained, long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity.12,13 In addition, permanent weight loss through bariatric surgery reduces the relative risk of death from 35% to 89%, depending on the study,14–18 and produces substantial pharmaco-economic benefits.19

Despite these benefits, bariatric surgery is difficult to access in Canada. Few resources, monetary or otherwise, are made available to treat this condition. Some provinces do not accept severe obesity as a chronic disease and thus do not include bariatric surgery as an insured service in their health care plans. Provinces that consider bariatric surgery to be an insured service have difficulty providing timely access for obese patients for a variety of reasons. We performed a detailed analysis of a prospectively maintained bariatric surgery database in a large Quebec centre and conducted a Canada-wide survey of centres and surgeons offering bariatric surgery to obtain a more accurate estimate of waiting times for the procedure in this country.

Methods

We considered patients to be eligible for bariatric surgery based on the National Institutes of Health consensus conference in 1991, which stated unequivocally that surgery is indicated in patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater or patients with a BMI of 35–40 kg/m2 who have clinically important comorbidity (e.g., type II diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, weight-bearing osteoarthropathy).20 Using this definition, we first carried out a phone survey of key members of the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons (CABPS) to determine how many eligible patients they were processing for bariatric surgery and to identify the various bottlenecks that could contribute to prolonged waiting times for this surgery. The Institutional Review Board of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) approved the maintenance of the bariatric surgery database, the retrieval of unidentified information (no patient identifiers are circulated or published) and the survey collection and results.

Using the self-reported estimates from this survey, we designed a paper survey instrument and sent it out to all surgeons and hospitals in Canada offering bariatric surgery. Our intent was to collect self-reported estimates based on registry data from commercial or home-grown databases for data-processing and analysis.

In addition, we performed a detailed analysis of the patient flow for bariatric surgery at the MUHC. The MUHC has been performing bariatric surgery since 1964 and has maintained a prospectively collected bariatric surgery registry since 1983. We cross-referenced this prospective database for mortality among patients waiting for bariatric surgery. The MUHC bariatric surgery staff regularly call patients waiting to advance to the next stage of their evaluation process. If they learn that a patient waiting for bariatric surgery has died, all attempts are made to determine the cause of death. The patient record is then flagged as “deceased while waiting” and closed.

Results

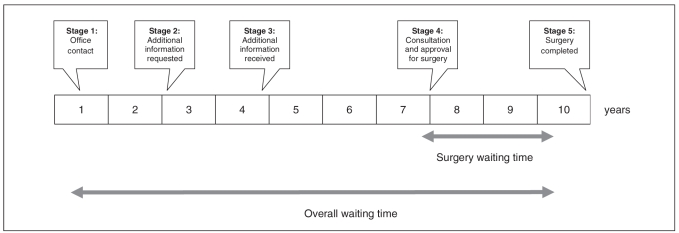

On the phone survey, the 3 largest bariatric surgery centres in Quebec reported that when patients contacted their centre, they asked for a weight and height to calculate patients’ BMI and a list of obesity-associated comorbidities. If the centre declared patients eligible for bariatric surgery, they registered them as “office contacts” in the bariatric surgery registry or equivalent and gave them a sequence number. As patients received their surgeries and exited the waiting list, other patients were moved forward according to the scheme depicted in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

The various stages of waiting for bariatric surgery in a typical bariatric surgery centre. The timing between stages varies widely at each centre.

This patient flow was confirmed in responses to the larger paper survey by most of the centres. Each centre reported variations of the data from the MUHC process shown in Table 1. This patient flow process resulted in 5 stages of waiting or bottlenecks. At the MUHC, patients were bottlenecked at stages 1–3 to limit the time in stage 4–5 to less than 2 years. According to this centre, if patients were moved more rapidly through the various stages and bottlenecked at stage 4, the time to surgery could be as long as 8 years (based on the current available resources). This prolonged wait is more than likely to result in worsening of the obesity-associated diseases and several clinical and medico-legal scenarios.

Table 1.

Patient waiting list staging for bariatric surgery at the McGill University Health Centre, as of Jun. 30, 2008

| Stage | Details | No. of patients on waiting list |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Office contact/consult request | 520 |

| 2 | Bariatric surgery information kit and questionnaire sent to patient | 650 |

| 3 | Completed questionnaire and pertinent information received from patient; screened patients waiting to see bariatric surgeon | 607 |

| 4 | Patients evaluated by surgeon and approved for surgery; official admission request completed | 217 |

| 5 | Surgery performed (January to June 2008) | 49 |

The phone survey identified a common theme of lack of resources, mainly operating room time and postoperative beds, as contributing to prolonged waits for patients seeking bariatric surgery. The follow-up paper survey provided detailed data from all the Quebec centres (Table 2). The number of patients bottlenecked at the various stages varied according to the local policies at each centre. At the end of 2007, there were 4868 patients waiting for bariatric surgery in Quebec; 716 surgeries were performed in Quebec that year. We calculated the average waiting time, defined as the wait from office contact to the actual surgery, by dividing the number of patients waiting by the number of surgeries performed for the year. The average waiting time for bariatric surgery in Quebec for 2007 was just under 7 years.

Table 2.

The number of patients waiting for surgery (stages 1–5) and the number of bariatric surgeries performed at each centre in the province of Quebec in 2007

| McGill University Health Centre | Université Laval | Hôpital Val-Dor | Centre Hospitalier Université de Montréal | Centre Hospitalier Université Sherbrooke | Hôpital Sacré-Cœur de Montréal | Centre Hospitalière Pierre Boucher | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, no. | |||||||

| Office contact/consult request | 870 | 836 | 0 | 0 | 130 | 90 | 455 |

| Office consultation date given to patient | 607 | 93 | 21 | 90 | 6 | 12 | 38 |

| Patient evaluated by the multidisciplinary team and placed on the hospital surgery list | 217 | 710 | 55 | 160 | 15 | 78 | 385 |

| Total | 1694 | 1639 | 76 | 250 | 151 | 180 | 878 |

| No. of bariatric surgeries performed in 2007 | 138 | 327 | 24 | 52 | 11 | 65 | 99 |

| Waiting time (all stages), yr | 12.3 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 13.7 | 2.8 | 8.9 |

The follow-up paper survey also provided detailed self-reported estimates from 12 of 14 centres who responded to the Canada-wide survey, a response rate of 85%. Table 3 summarizes the data from all 12 Canadian centres for 2007 (including Quebec). There were a total of 6783 patients waiting for bariatric surgery across Canada in 2007; the waiting time for bariatric surgery in Canada was just over 5 years.

Table 3.

Patients waiting for bariatric surgery at 11 Canadian centres and the calculated waiting time* at each centre

| Centre | No. of patients waiting | No. of surgeries, 2007 | Wait time, yr |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 180 | 65 | 2.8 |

| 2 | 76 | 24 | 3.2 |

| 3 | 250 | 52 | 2.1 |

| 4 | 151 | 11 | 13.7 |

| 5 | 878 | 99 | 8.9 |

| 6 | 1639 | 329 | 5.0 |

| 7 | 1694 | 138 | 12.3 |

| 8 | 300 | 200 | 1.5 |

| 9 | 320 | 82 | 3.9 |

| 10 | 860 | 205 | 3.9 |

| 11 | 435 | 88 | 4.9 |

| Totals | 6783 | 1313 | — |

| Average | 5.2 |

Total no. of patients waiting/no. of surgeries for 2007.

Twelve patients died while waiting for bariatric surgery at the MUHC (Table 4). The mean age of these patients was 46 (standard deviation [SD] 8.3) years, which was slightly higher than that of patients who are currently waiting (mean 42, SD 9.2 yr). The BMI of patients who died was also higher than that of patients still waiting (56.8, SD 11.8 yr v. 51.8, SD 9.8 yr, p = 0.048). Six of the 12 patients who died were men (50%), a proportion that is much higher than the proportion of men on the waiting list for the surgery (24%). The degree of obesity-associated conditions was not strikingly different between the 2 groups. The Obesity Surgery Mortality Risk Score category was not significantly different between the 2 cohorts. The cause of death was unknown in 5 patients.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the 12 identified patients who died while on the waiting list for bariatric surgery at the McGill University Heatlh Centre

| Patient no. | Age, yr | Sex | BMI, kg/m2 | OS-MRS | Wait, yr | Comorbidity | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | M | 63 | B | 8 | Type II diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, heart disease | Liver failure |

| 2 | 45 | F | 41 | A | 3 | Osteoarthritis, stress incontinence, chronic bronchitis | Unknown |

| 3 | 36 | F | 62 | B | 3 | Osteoarthritis (cane), stress incontinence, chronic venous stasis, melanoma right eye (7 yr) | Unknown |

| 4 | 50 | F | 51 | A | 5 | Type II diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis | Myocardial infarction |

| 5 | 55 | M | 75 | C | 1 | Osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, severe shortness of breath, deep vein thrombosis, venous stasis ulcers | Unknown |

| 6 | 32 | M | 71 | B | 2 | Severe asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, venous stasis | Asthmatic attack and cardiac arrest |

| 7 | 33 | F | 44 | A | 3 | Type I diabetes, osteoarthritis, chronic depression | Multiple organ failure due to diabetic complications |

| 8 | 56 | M | 46 | B | 2 | Osteoarthritis, venous stasis ulcers, hypertension, remote tuberculosis | Pulmonary edema, lung cancer at autopsy |

| 9 | 45 | M | 61 | B | 5 | Osteoarthritis, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, high cholesterol and lipids | Unknown |

| 10 | 54 | F | 66 | B | 2 | Osteoarthritis, venous stasis ulcers, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension | Unknown |

| 11 | 48 | F | 43 | A | 3 | Osteoarthritis, stress incontinence, depression | Myocardial infarction |

| 12 | 43 | M | 49 | B | 7 | Cardiomyopathy, hypertension, type II diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, venous stasis ulcers | Pulmonary embolus |

BMI = body mass index; OS-MRS = Obesity Surgery Mortality Risk Score.

Discussion

A discussion of waiting times for any type of surgery must include the definition of the waiting time: specifically, where or when does the patient enter the queue and what part of the time in the queue is the agreed-upon waiting time? According to the waiting time definitions used by most health authorities, in particular the Ministère de la Santé et Services sociaux in Quebec, the waiting time for surgery starts when an admission request is submitted by the surgeon’s office to the admitting office of the hospital. This is the surgery waiting time depicted in Figure 1. Such a definition may be applicable to patients who are likely to wait 4–6 weeks, the current acceptable waiting time for cancer surgery; however, this same definition is inappropriate for bariatric surgery because the enormous numbers of patients requesting this surgery would lead to a clinically unacceptable period from declaring a patient fit for surgery to the actual surgery. The realistic waiting time for bariatric surgery must be defined as the overall waiting time depicted in Figure 1.

Our study demonstrates clearly that waiting times for bariatric surgery in Canada are too long, at an average of 5 years. By comparison, the Fraser Institute and the Wait Times Alliance benchmarks for reasonable surgical waiting times vary from 8 weeks for cancer surgery to 18 months for cosmetic surgery. The inappropriate waiting time for bariatric surgery stems from the lack of capacity for bariatric surgery in Canadian health centres and hospitals. Assuming that 2%–4% of the Canadian adult population is morbidly obese, a conservative estimate of the number of Canadians who might be eligible for bariatric surgery ranges from 600 000 to 1 200 000. Assuming that 3% of the morbidly obese population of Canada requests this surgery over the next 12 months, surgery would be required for anywhere from 18 000 to 36 000 patients. We identified 1313 bariatric surgeries performed in 2007. This is more than double that of the latest Canadian data available, which identified an average of 500 bariatric surgeries performed per year from 1993 to 2003.21 A subsequent publication22 using data for the Discharge Abstract Database of the Canadian Institute for Health Information showed that in Canada, unlike the United States, the number of surgeries performed annually from 1997 to 2004 had not increased above an average of about 800. Both these studies underestimate the yearly number of bariatric surgeries in all of Canada because they do not include data from Manitoba and Quebec. Quebec has 2 of the largest bariatric surgery programs in Canada: the MUHC performs about 150 bariatric surgeries per year and Université Laval performs about 250. Our study shows that the number of surgeries currently being performed in Canada clearly cannot meet the demands.

The province of Ontario recognizes this lack of capacity and, since 2004, sends more than 500 patients per year to the United States for this surgery.23

It is not surprising that prolonged waits of more than 5 years for bariatric surgery lead to deaths among patients on the waiting list, given the devastating obesity-associated diseases that afflict these patients. Our study, which showed a reduction in the relative risk of death following long-term weight loss through bariatric surgery, had follow-up periods as short as 5 years.14 This suggests that the average wait of just over 5 years for bariatric surgery in Canada can put patients at increased risk of death. Silva and colleagues24 examined this issue in patients waiting for years for bariatric surgery in Brazil. They contacted 1329 patients eligible for surgery with their group by telephone or telegram in 2005. Of these, 612 (46%) could not be reached and 117 (8.8%) had their surgeries in other hospitals. Only 7 patients (0.53%) changed their minds and did not wish to have surgery despite being morbidly obese. Eight patients (0.6%) died while waiting for the procedure. The mean waiting time was just under 3 years.

The MUHC identified 12 patients (0.6%) who died while waiting for bariatric surgery, without a formal call-back of all 2178 patients in the queue (as of the end of 2008). In our limited analysis, we could not identify any reliable trends for greater risk of death using the usual indicators of BMI, age and comorbid diseases. The male: female ratio among patients who died while waiting for surgery was not representative of the usual ratio in most centres. Since the current Canadian health care system capacity is inadequate to eliminate these waiting lists in the next few years, further studies are needed to determine the risk factors for dying on a bariatric surgery waiting list so that patients may be prioritized accordingly. Should a 55-year-old patient with a of BMI 58 kg/m2, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea and destroyed hip and knee joints have equal status in the queue as a 20-year-old patient with a BMI of 60 kg/m2 and no obesity-associated diseases? Given that long-term weight loss through bariatric surgery has now been shown to reduce the relative risk of cancer after only a 5-year follow-up, the answer is not easily determined.25

In 2005, the Agence d’évaluation des technologies et des modes d’intervention en santé (AETMIS) in Quebec recommended that “the Ministère de la Santé et Services sociaux and other decision-makers concerned with the problem of morbid obesity precisely identify current and future needs in bariatric surgery, establish an action plan to increase the capacity to provide this treatment and ensure that patients in the different settings and regions have fair access to these services.”26 The AETMIS recommended that Quebec susbtantially increase its capacity for bariatric surgery from the current 716 patients per year to more than 3000 by 2010 to meet the demand of the population. In Ontario, an arm’s-length expert advisory committee to the Ontario health care system and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, stated in their report of December 2005 that the province of Ontario increase bariatric surgery capacity to at least 3500 surgeries per year.23 Acting on this recommendation, the province of Ontario recently announced a Can$75 million investment to increase the number of gastric bypass surgeries as part of a Can$741 million strategy for the treatment of diabetes, which costs the province Can$5 billion per year. The Quebec response to the AETMIS recommendations and to those of a Blue Ribbon committee of obesity treatment experts tabled in October 2007 is pending.

Given that bariatric surgery saves lives and money and that waiting times for bariatric surgery in Canada are longer than 5 years, our health policy-makers must address this issue immediately.

Footnotes

Presented in part as a poster at the Canadian Surgery Forum in Halifax, NS, Sept. 10–13, 2008.

Competing interests: Dr. Christou receives an unrestricted educational grant from Ethicon Endosurgery Canada. Dr. Efthimiou’s fellowship was partially sponsored by Ethicon Endosurgery UK.

Contributors: Dr. Christou designed the study and wrote the article. Both authors acquired and analyzed the data, reviewed the article and gave final approval for its publication.

References

- 1.Rapport du groupe d’experts en santé publique. Médecine et chirurgie bariatrique avec la collaboration des agences de la santé de la capitale nationale, de la Mauricie-Centre-Du-Québec et Montréal. L’organisation de la médecine et chirurgie bariatriques au Québec. 2007;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894(i–xii):1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abelson P, Kennedy D. The obesity epidemic. Science. 2004;304:1413. doi: 10.1126/science.304.5676.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrance GM, Hooper MD, Reeder BA. Trends in overweight and obesity among adults in Canada (1970–1992) evidence from national surveys using measured height and weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:797–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzmarzyk PT. The Canadian obesity epidemic, 1985–1998. CMAJ. 2002;166:1039–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazards of obesity. Nature. 1968;220:330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman JM. A war on obesity, not the obese. Science. 2003;299:856–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1079856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fappa E, Yannakoulia M, Pitsavos C, et al. Lifestyle intervention in the management of metabolic syndrome: Could we improve adherence issues. Nutrition. 2008;24:286–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hainer V, Toplak H, Mitrakou A. Treatment modalities of obesity: What fits whom? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S269–77. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grodstein F, Levine R, Troy L, et al. Three-year follow-up of participants in a commercial weight loss program. Can you keep it off. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1302–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christou NV, Look D, Maclean LD. Weight gain after short- and long-limb gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years. Ann Surg. 2006;244:734–40. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217592.04061.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brolin RE. Bariatric surgery and long-term control of morbid obesity. JAMA. 2002;288:2793–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:416–23. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137343.63376.19. discussion 423–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busetto L, Mirabelli D, Petroni ML, et al. Comparative long-term mortality after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus non-surgical controls. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.06.003. discussion 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peeters A, O’Brien PE, Laurie C, et al. Substantial intentional weight loss and mortality in the severely obese. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1028–33. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31814a6929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampalis JS, Liberman M, Auger S, et al. The impact of weight reduction surgery on health-care costs in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:939–47. doi: 10.1381/0960892041719662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institutes of Health. [(accessed 2009 May 13)];Gastrointestinal surgery for severe Obesity. NIH Consensus statement online. 1991 Mar. 25–27. 9(1):1–20. [cited 2009 Apr. 16] Available: http://consensus.nih.gov/1991/1991GISurgeryObesity084html.htm. [PubMed]

- 21.Padwal RS, Lewanczuk RZ. Trends in bariatric surgery in Canada, 1993–2003. CMAJ. 2005;172:735. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jokovic A, Frood J, Leeb K. Bariatric surgery in Canada: Obesity rates for Canadian adults are much higher today than in the past; however, rates of bariatric surgery, a treatment for high-risk severely obese individuals, have not risen in parallel. Health Policy. 2006;1:64–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee. OHTAC recommendation. Bariatric surgery. January 21, 2005. Toronto (ON): OHTAC; 2005. [(accessed 2009 Apr. 16)]. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/tech/recommend/rec_baria_012105.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva M. Mortality of morbidly obese patients on the waiting list for bariatric surgery [abstract] Obes Surg. 2006;16:401–2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christou NV, Lieberman M, Sampalis F, et al. Bariatric surgery reduces cancer risk in morbidly obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:691–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassen-Khodja R, Lance JMR Agence d’évaluation des technologies et des modes d’intervention en santé (AETMIS) Surgical treatment of morbid obesity. An update. Montréal (QC): AETMIS; 2006. [(accessed 2009 Apr. 16)]. Available: www.aetmis.gouv.qc.ca/site/download.php?f=d76d1f910aff4f2e92bcbe0520e21bd8. [Google Scholar]