Abstract

Considerable indirect evidence suggests that the type 2 deiodinase (D2) generates T3 from T4 for local use in specific tissues including pituitary, brown fat, and brain, whereas the type I deiodinase (D1) generates T3 from T4 in the thyroid and peripheral tissues primarily for export to plasma. From studies in deiodinase-deficient mice, the importance of the D2 for local T3 generation has been confirmed. However, the phenotypes of these D1 knockout (KO) and D2KO mice are surprisingly mild and their serum T3 level, general health, and reproductive capacity are unimpaired. To explore further the importance of 5′deiodination in thyroid hormone economy, we used a mouse devoid of both D1 and D2 activity. In general, the phenotype of the D1/D2KO mouse is the sum of the phenotypes of the D1KO and D2KO mice. It appears healthy and breeds well, and most surprisingly its serum T3 level is normal. However, impairments in brain gene expression and possibly neurological function are somewhat greater than those seen in the D2KO mouse, and the serum rT3 level is elevated 6-fold in the D1/D2KO mouse but only 2-fold in the D1KO mouse and not at all in the D2KO mouse. The data suggest that whereas D1 and D2 are not essential for the maintenance of the serum T3 level, they do serve important roles in thyroid hormone homeostasis, the D2 being critical for local T3 production and the D1 playing an important role in iodide conservation by serving as a scavenger enzyme in peripheral tissues and the thyroid.

D1 and D2 are not essential for the maintenance of the serum T3 level, but are important for TH homeostasis, the D2 being critical for local T3 production, and the D1 participating in iodide conservation by serving as a scavenger enzyme in peripheral tissues and the thyroid.

T4, the major thyroid hormone (TH) present in both thyroid and plasma can be converted by 5′deiodination (5′D) to T3 (1,2) by the types 1 and 2 deiodinases (D1 and D2). The type 3 deiodinase (D3) catalyzes the 5-deiodination (5D) of both T4 and T3 to their relatively inactive derivatives, rT3 and 3,3′-diiodothyronine, respectively (2,3). The D1 can also inactivate TH by catalyzing the 5D of their sulfated derivatives (4).

It is widely accepted that T3 is generated from T4 by the D1 in liver and kidney primarily for export to the plasma (5,6), whereas the D2 generates T3 for local use in specific tissues such as pituitary, brown adipose tissue (BAT) and brain (2). However this role for the D1 has been challenged recently by the finding that the plasma T3 level is maintained in D1-deficient mice (7,8,9), and estimates made in both rats (10) and humans (11) strongly suggest that a significant fraction of the plasma T3 is generated by the D2.

To determine the precise physiological roles of the D1 and the D2, we created D1-deficient (D1KO) and D2-deficient (D2KO) mice (9,12). Given the widespread physiological effects of TH in mammals, both during development and in the adult, we expected these mice to exhibit marked functional impairment. Somewhat surprisingly, both have a normal serum T3 level and their general health, growth, and reproductive capacity are seemingly unimpaired. Nevertheless, the importance of the D2 for local generation of T3 from T4 has been confirmed; D2KO mice have significant deficits in TSH regulation (12), thermogenesis (13), and auditory function (14), and brain T3 content is significantly reduced, even though the brain T4 content is elevated (15). However, this reduction in brain T3 content results in only minimal changes in the mRNA levels of several TH-responsive genes and has little effect on such functions as locomotion, learning and memory (15), functions that are significantly impaired in hypothyroid mice (15,16). The reasons for this apparent paradox are unclear.

The present studies were carried out to clarify the physiological roles of 5′D and to determine whether the relatively mild phenotypes of mice lacking only one 5′D are due in part to the ability of each deiodinase to compensate for the other. Thus, we created a double D1/D2KO mouse and determined its phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type (WT), D1KO, D2KO, and double D1-plus D2-deficient (D1/D2KO) mice, all in the C57/BL6 background, were used in this study. The WT, D1KO and D2KO mice came from our established colonies (9,12). The D1/D2KO mice were obtained by cross-breeding the D1KO and D2KO mice. To generate hypothyroid pups, the dams were placed on drinking water containing 0.1% methimazole plus 1% KClO4 throughout pregnancy and lactation. Mice were housed with controlled lighting, 12 h light, 12 h dark, and temperature in the barrier section of the Dartmouth Medical School animal research facility. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dartmouth Medical School.

Tissue preparation

The following tissues were harvested from mice at neonatal day (P) 15: liver, kidney, heart, skin, muscle, intestine, lung, BAT, thyroid, brain, and pituitary. All tissues were processed for determination of deiodinase activity. Brain regions [cerebellum (Cb), cerebral cortex (CCx), and hypothalamus] were also processed for determination of TH content. Total RNA was isolated from pieces of Cb, CCx, and hypothalamus using TRIzol, (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Details of the tissue harvesting and processing methods have been described previously (15).

Determination of 5′D and 5D activities

5′D and 5D activities were assayed according to our published methods (17,18). The substrates, [125I]rT3, [125I]T3, and [125I]T4 (specific activities ∼1000 μCi/μg), were obtained from PerkinElmer Inc. (Norwalk, CT) and were purified by chromatography using Sephadex LH-20 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) before use. Deiodination is expressed as femtomoles of iodide or product generated per hour per milligram protein.

Assays for T4 and T3 in serum and tissue samples

Total T4 and T3 concentrations in serum were determined using the Coat-A-Count RIA total T4 and total T3 kits (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX). The T3 assay was modified for mouse serum as previously described (15), and the T3 values obtained were corrected for the 0.38% cross-reactivity of the T4 in the serum sample.

The contents of T3 and T4 in brain tissue were determined using our highly sensitive nonequilibrium RIA assay procedures (19). The T4 and T3 antibodies were obtained from Fitzgerald Industries International, Inc. (Concord, MA): T3 antibody, catalog no. 20-TR45, cross-reactivity with T4 less than 0.38%; T4 antibody, catalog no. 20-TR40, cross-reactivity with T3 less than 7.5%. The assay sensitivity was approximately 2 pg/tube for T3 and 4 pg/tube for T4.

Serum rT3 concentration was also measured using the same highly sensitive nonequilibrium RIA assay procedures. The rT3 antibody was a gift from Dr. L. Braverman (20) and ultrapure unlabeled rT3 was obtained from Henning Co. (Berlin, Germany). The assay sensitivity was approximately 2 pg/tube.

The serum TSH levels were determined by Dr. A. F. Parlow using his double-antibody method (12).

Determination of total T4 and T3 content in the thyroid gland

Thyroid glands were hydrolyzed, extracted with ethanol, the extracts evaporated to dryness, and the residue dissolved in 250 μl RIA buffer and appropriately diluted for assay as previously described (9).

Analysis of mRNA levels by real-time PCR

The RNA samples were subjected to deoxyribonuclease treatment, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR using the kits, primers, and methods employed in a previous study (15).

Studies of the in vivo turnover of [125I]T4 and [125I]T3

This study was carried out in special cages designed to permit the separate collection of urine and feces (9). WT and D1/D2KO mice (12 wk old) were injected ip with T4 (2 or 20 μg per 100 g body weight (BW)] or T3 (1.5 or 16 μg per 100 g BW), labeled with approximately 0.5 × 106 cpm of the corresponding radioactive hormone (purified immediately before use as described above). Urine and feces were collected over the following 48 h and their radioactive contents assessed. To determine the fraction of urinary radioactivity that was in the form of iodide, aliquots of urine were counted before and after their passage through a column of AG 50W-X8(H−) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), a resin that adsorbs iodothyronines. At the end of the 48-h period, mice were euthanized and their thyroids removed and counted. No significant amount of radioactivity was taken up by the thyroid gland.

Clearance of exogenous T4 and T3 from serum

To determine whether D1/D2KO mice have an impaired ability to clear T4, blood samples were obtained from 10-wk-old WT and D1/D2KO mice immediately before and 18 h after they were injected ip with 20 μg per 100 g BW T4 and the serum was assayed for T4.

To determine whether D1/D2KO mice have an impaired ability to clear T3, 10-wk-old WT and D1/D2KO mice were implanted sc with an Alzet osmotic minipump (model 1002, dimensions: 1.5 cm length × 0.6 cm diameter; Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA) designed to administer a constant dose of a solution of T3 (15 μg per 100 g BW · d) or vehicle over a period of 14 d. None of the animals suffered any ill effects of the implants, either generally or in the area of the pump. After 12 d, serum was obtained and assayed for T4 and T3 content.

Assessment of neurological function

Rotarod apparatus to test balance and agility

Mice were subjected to two sessions on the rotarod apparatus per day, morning and afternoon, for 8 d, and a single morning session on d 9. Each session involved three trials. On the first day, the mouse was placed on the rotarod as it was rotating at 10 rpm. Once the mouse had remained on the rotarod for 60 sec in all three trials, the speed was increased by 2.5 rpm for the next session. Otherwise, the speed was held at 10 rpm until the mouse had mastered that speed.

Vertical pole test for agility

In this test, mice were placed face upward near the top of a vertical pole. Normally a mouse will invert itself, wrap its tail around the pole and run to the base. The time to invert and the time to descend were measured over a maximum period of 60 sec. If they did not descend, they were scored at 60 sec.

Morris water maze 5-d test for learning and memory

We have published full details of this test (15). Briefly, a tub, about 100 cm in diameter, filled with water made opaque with paint powder and containing a small platform submerged just below the water surface was used. On each of 5 consecutive days, the mouse was subjected to four trials in which it was placed in the water (the entry points being from all four quadrants of the tub) and the time taken (up to 1 min) for it to climb on to the platform measured. After the test on d 5, the platform was removed, the mouse placed in the water, and its swimming pattern videotaped for 60 sec. The data were then analyzed to determine the time spent in the quadrant in which the platform had been located (probe test). Finally, the platform was replaced so that it was clearly visible. The mouse was again placed in the water and the time taken for it to climb on to the platform recorded (visible cue test).

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± se. Statistical analyses were carried out using the GB-Stat PPC 6.5.4 computer program (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD). For comparison of values obtained in WT and D1/D2KO mice, Student’s t test was used. For comparisons among three or more groups, one-way ANOVA was performed and the differences were assessed using Fisher’s least significant differences (protected t test) test. Statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05.

Results

The general phenotype of the D1/D2KO mouse appears to be no different from the WT or single D1KO or D2KO mice (9,12). On the basis of 15 WT litters and 17 D1/D2KO litters, WT and D1/D2KO mice have an average of 6.2 and 6.9 pups/litter, respectively. The average WT pup weight at 10, 15, and 20 d was 5.0, 6.2, and 7.6 g, respectively, and corresponding D1/D2KO weights were 5.0, 6.7, and 8.0 g. The higher mean weight of the D1/D2KO pups at 20 d was not significant.

By 8 wk and older, the mean weight of the D1/D2KO mice was generally slightly lower (average 5%) than that of WT mice of comparable age; the difference was usually significant (data not shown).

No 5′D activity was detected in any of the D1/D2KO mouse tissues examined (liver, kidney, brain, skin, BAT, thyroid, pituitary, muscle, intestine, and lung). However, significant 5D activity was present and the level of activity was comparable in WT and D1/D2KO mouse brain. At P15, 5D activity in the various brain regions of WT vs. D1/D2KO mice, expressed in femtomoles per hour per milligram protein, was: Ccx, 998 ± 235 vs. 1356 ± 248 (P = NS), hypothalamus+striatum, 1458 ± 294 vs. 1165 ± 210 (P = NS). 5D activity in whole brain at P84 was 723 ± 64 vs. 812 ± 52 (P = NS).

TH and TSH in serum

Serum T4, T3, rT3, and TSH levels in 12-wk-old D1/D2KO mice, together with corresponding levels in the single KO and WT mice, are shown in Table 1. Surprisingly, the serum T3 level in the D1/D2KO mice is no different from that in WT or single KO mice. However, the serum T4 level in the D1/D2KO mouse is almost twice that in WT mice and significantly higher than the elevated level present in each of the single KO mice. The serum TSH level in the D1/D2KO is 2.6 times that in the WT and D1KO mice and comparable with that observed in the D2KO animal. The difference among species in the serum rT3 level was the most remarkable. Although no difference in the serum rT3 level was noted between D2KO and WT mice, the level is increased 2-fold in the D1KO and 6-fold in the D1/D2O.

Table 1.

Serum T4, T3, rT3, and TSH levels in WT and deiodinase-deficient mice

| Group | T4 (μg/100 ml) | T3 (ng/100 ml) | rT3 (ng/100 ml) | TSH (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (22) | 3.3 ± 0.15 | 47 ± 4.2 | 19 ± 0.3 | 201 ± 10 |

| D1KO (12) | 5.0 ± 0.17 | 51 ± 2.7 | 39 ± 4.7 | 194 ± 10 |

| D2KO (19) | 4.2 ± 0.20 | 57 ± 5.2 | 23 ± 3.2 | 645 ± 103 |

| D1/D2KO (21) | 6.3 ± 0.61 | 40 ± 8.1 | 113 ± 1.5 | 523 ± 123 |

| Significant differences: D1/D2KO vs. | ||||

| WT | P < 0.001 | NS | P < 0.001 | P < 0.025 |

| D1KO | P < 0.05 | NS | P < 0.001 | P < 0.025 |

| D2KO | P < 0.005 | NS | P < 0.001 | NS |

The numbers of mice per group for T4, T3, and TSH are given in parentheses. For rT3 there was a minimum of eight mice per group. NS, Not significant.

The serum T4 level is also elevated in the neonatal D1/D2KO mouse; at P15, the serum T4 level (micrograms per 100 ml) in WT and D1/D2KO mice was 5.1 ± 0.4 and 7.8 ± 0.9 (P < 0.05), respectively, and at P21, 3.7 ± 0.21 and 10.3 ± 0.76 (P < 0.001), respectively.

Thyroid weight, histology, and TH content

Thyroid weight is normal in the D1/D2KO mice. At 8 wk, WT and D1/D2KO mouse thyroids weighed 2.5 ± 0.2 and 2.4 ± 0.1 mg [P = NS (not significant)], respectively. On microscopic examination of sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, the structural features of the D1/D2KO mouse thyroid gland were comparable with those of the WT thyroid (data not shown).

The D1/D2KO thyroid contains at least as much T4 and T3 as does the WT thyroid. On the basis of data obtained in four glands/genotype, the T4 content in 12-wk-old WT and D1/D2KO thyroids was 220 ± 19 and 271 ± 22 ng/thyroid (P = NS), respectively; the T3 content was 74 ± 15 and 128 ± 17 ng/thyroid (P < 0.05), respectively. These data indicate that T3 production in the thyroid gland is not compromised by the absence of the D1.

Urinary and fecal excretion of thyroid hormones and their metabolites

To determine how the absence of both 5′Ds influences the renal and fecal excretion of T4 and T3 and their derivatives, the disposition of radioactivity after a single injection of either [125I]T4 or [125I]T3 was measured. Because these hormones were labeled only in their phenolic (outer) ring, the [125I]iodide excreted represented only iodide released by 5′D. Furthermore, only iodothyronine derivatives that still retained [125I]iodine in their phenolic ring could be detected in the feces. After injection of [125I]T4 (20 μg per 100 g BW), both WT and D1/D2KO mice excreted 75% or more of the total radioactivity injected during the subsequent 48-h period. However, the pattern of excretion in the two genotypes was very different (Fig. 1, upper panel). The WT mice excreted approximately 25% of the injected radioactivity in the urine and 50% in the feces. In contrast, radioactivity was excreted only in the feces of the D1/D2KO mice; none was noted in the urine. Similar patterns were obtained after injection of a lower dose of [125I]T4 (2 μg per 100 g BW, data not shown). Analysis of fecal samples from both genotypes revealed that more than 99% of the radioactivity excreted in the feces was organically bound.

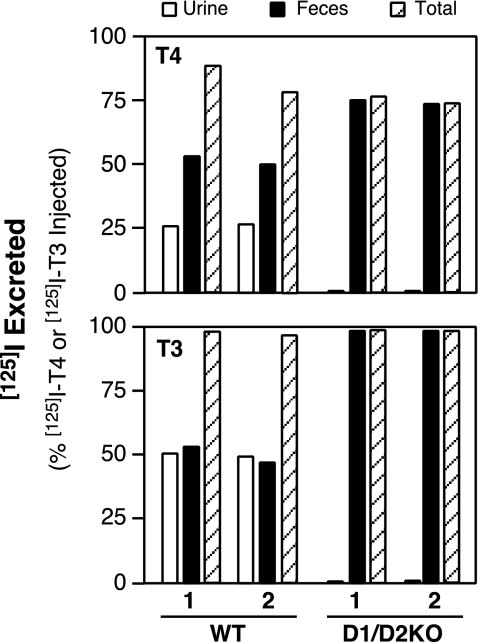

Figure 1.

Excretion of radioactivity by WT and D1/D2KO mice during the 48-h period after a single ip injection of either [125I]T4 (20 μg per 100 g BW) or [125I]T3 (16 μg per 100 g BW). Bars represent the values obtained in individual mice.

After the injection of [125I]T3 (16 μg per 100 g BW), both WT and D1/D2KO mice excreted more than 97% of the radioactivity in the subsequent 48 h. The WT mice excreted almost equal amounts of radioactivity in the urine and feces, whereas the D1/D2KO mice excreted the radioactivity exclusively in the feces (Fig. 1, lower panel). Similar patterns were obtained after injection of 1.5 μg T3 per 100 g BW (data not shown). These in vivo experiments confirm the absence of all 5′D activity in the D1/D2KO mouse.

Clearance of T4 and T3 from the circulation

In this study the serum T4 level was determined immediately before and 18 h after WT and D1/D2KO mice (n = 9 and 11, respectively) were injected ip with 20 μg per 100 g BW T4. Before injection, the T4 level (micrograms per 100 ml) in WT and D1/D2KO mice was 5.3 ± 0.16 and 8.1 ± 0.32, respectively; 18 h after injection of the T4, the level was 22.5 ± 0.83 in the WT mice and 19.9 ± 0.93 in the D1/D2KO mice. At this time the serum rT3 level in WT and D1/D2KO mice was 566 ± 49 and 705 ± 37 ng per 100 ml (P < 0.05), respectively. Thus, it appears that the capability to clear from the serum a relatively large dose of T4 is not impaired in the D1/D2KO mouse despite its inability to carry out 5′D.

In other studies the serum TH levels were compared in three groups of mice (six per group) 12 d after they had been implanted with Alzet pumps containing either T3 (15 μg per 100 g BW per day) or vehicle: WT+vehicle, WT+T3, and D1/D2KO+T3. The serum T4 concentration in the three groups at the end of the experimental period was 3.7 ± 0.34, 0.35 ± 0.18, and 0.9 ± 0.43 μg per 100 ml, respectively. The corresponding serum T3 concentration was 77 ± 3.1, 108 ± 12.8, and 94 ± 11.8 ng per 100 ml. These data strongly suggest that the ability to clear T3 from the circulation is also not impaired in the D1/D2KO mouse.

TH content in brain

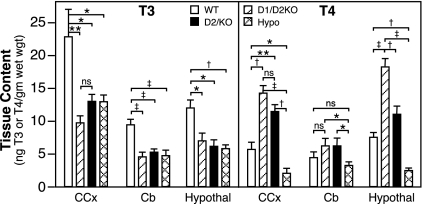

The T3 and T4 contents of three brain regions of the D1/D2KO mouse at P15 were determined and compared with those in WT, D2KO, and hypothyroid mice (Fig. 2). The T3 content in the CCx, Cb, and hypothalamus of the D1/D2KO mouse was reduced to approximately 50% of that in the corresponding brain areas of WT mice. This decrease was comparable with that seen in D2KO and hypothyroid mice.

Figure 2.

T3 and T4 contents in CCx, Cb, and hypothalamus of WT, D1/D2KO, D2KO, and hypothyroid (Hypo) WT mice at P15. Bars indicate the mean ± se of values obtained in extracts prepared from a minimum of 15 mice/group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.005; ‡, P < 0.001. ns, Not significant.

The mean total T4 content in the CCx and hypothalamus of the D1/D2KO mice was more than twice that in the corresponding areas of WT mice, and in the hypothalamus it was significantly higher than that in the D2KO mice (Fig. 2). In contrast, the T4 content of these two areas was significantly reduced in the hypothyroid mice (Fig. 2).

Although the mean T4 content of the Cb in the D1/D2KO and D2KO mice was elevated and that of the hypothyroid mouse was decreased, the values were not significantly different from that in the Cb of WT mice. However, the T4 content in the D1/D2KO and D2KO mice was significantly higher than that in the hypothyroid mice.

Levels of expression of T3-responsive genes in brain at P15

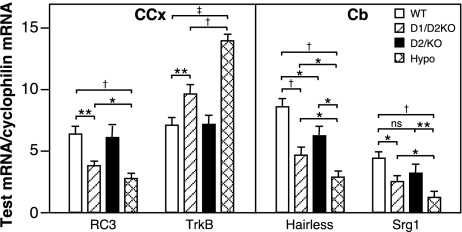

RC3, TrkB, Hairless, and Srg1 are T3-responsive genes that are expressed in neurons. The transcription of RC3, Hairless, and Srg1 is increased, and TrkB decreased, by TH during the developmental period in rodents (21,22). In the D1/D2KO mouse, significant changes in the levels of mRNA for RC3 and TrkB in the Ccx and in Hairless and Srg1 in the Cb were observed (Fig. 3). However, even though the brain T3 content of the D1/D2KO mouse brain was reduced to the level equal to that in the hypothyroid mouse brain, the changes in mRNA levels of all four genes in the D1/D2KO brain were significantly less than those observed in the hypothyroid WT brain.

Figure 3.

Levels of mRNA of RC3 and TrkB in CCx and Hairless and Srg 1 in Cb of WT, D1/D2KO, D2KO, and hypothyroid WT mice at P15. Bars indicate the mean ± se of values obtained in RNA prepared from a minimum of 15 mice/group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.005; ‡, P < 0.001.

Assessment of neurobehavioral function

Reflexes

No differences were observed between the WT and D1/D2KO mice with respect to posturing, righting, eye blink, ear twitch, whisker-orienting reflex, constriction, and dilation of pupil or day of eye opening.

Locomotion and agility

In the 8-d test on the rotarod apparatus, none of the mice resorted to passive rotation and no differences in performance between the WT and D1/D2KO mice were observed (data not shown). The test used 11 WT and 10 D1/D2KO mice.

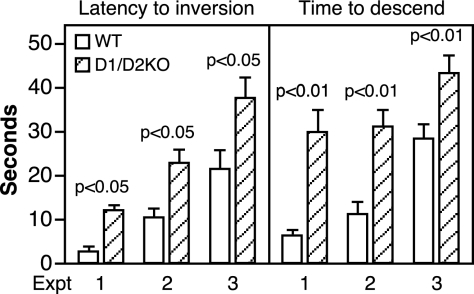

For the pole test, three separate experiments were performed using different groups of mice and a minimum of 10 mice/group. The behavior of the D1/D2KO mice on the pole was clearly abnormal. Instead of inverting and running down the pole like the WT mice, some D1/D2KO mice would invert and then quickly reverse back and run to the top of the pole, whereas others would slither down the pole sideways. With respect to the quantitative measurements made, the D1/D2KO mice were significantly slower than WT mice both to invert and to descend (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Performance of 10-wk-old WT and D1/D2KO mice on the vertical pole. In this test, the mouse was placed face upward near the top of a vertical pole. The time to invert and the time to descend were measured over a maximum period of 60 sec. Bars indicate the mean ± se of values obtained in three experiments, each with a minimum of 10 mice/group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Learning and memory

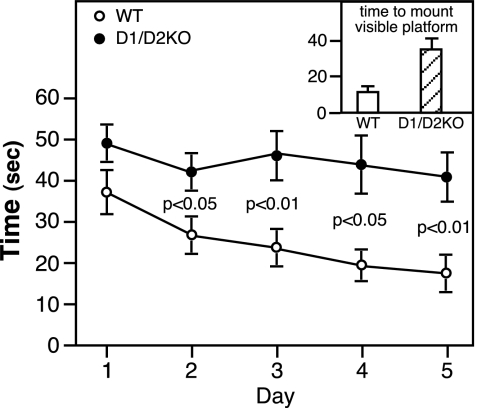

As indicated by the significantly shortened time taken to mount the invisible platform on d 2–5 in the Morris water maze test, WT mice exhibited clear learning and memory skills (Fig. 5). In contrast, the D1/D2KO mice showed little if any decrease in the time taken to mount the platform on d 2–5 and spent much less time swimming in the quadrant that had contained the submerged platform than did the WT mice: 7.6 ± 2.0 vs. 17.7 ± 3.0 min (P < 0.01). Taken alone, these findings would suggest impaired learning and memory skills in the D1/D2KO mice. However, the finding that the D1/D2KO mice took much more time than the WT mice to mount the platform when it was clearly visible (visible cue test, Fig. 5, inset) suggests that factors other than learning and memory are responsible for their relatively poor performance in the submerged platform and probe tests.

Figure 5.

Performance of 10-wk-old WT and D2KO mice in the Morris water maze test. See Materials and Methods for full details. Briefly, the test uses a circular tub filled with opaque water with a small platform located in one quadrant just below the water surface. On each of the 5 d, the mouse was placed in the water and the time taken for it to climb on to the platform recorded. On each day the test was repeated three times, the entry points being from all four quadrants of the tub. The circles indicate the mean ± se of the average time taken by each of the 12 mice/group on that day. Inset, The time taken on d 5 to mount the visible platform.

Discussion

The most striking finding in the present study is that a mouse devoid of all 5′D capability is able to maintain a normal serum T3 level when housed under standard laboratory conditions that include iodine sufficiency. This was unexpected, given the generally accepted view that 5′D processes are critical for T3 production in both the thyroid gland and extrathyroidal tissues (6,23,24,25), and raises the question as to what processes compensate for this lack of ability to use T4 as a source of T3 in the D1/D2KO mouse. Because the present results appear to rule out a reduced T3 clearance rate, thyroidal secretion of T3 must be enhanced; indeed, increased thyroidal secretion of both T4 and T3 would be expected in view of the elevated serum TSH level (26). In addition, the thyroidal content of T3 but not T4 is markedly increased in the D1/D2KO mouse, a factor that likely contributes to the maintenance of the serum T3 level. Another but less likely explanation for the maintenance of serum T3 homeostasis in the D1/D2KO mouse is that the distribution of T3 between the intra- and extracellular compartments is altered. Given that T3 is predominantly an intracellular hormone, a relatively small increase in the extracellular/intracellular T3 content of tissues might serve to maintain a normal serum T3 level. However, no physiological mechanism for such a redistribution is apparent.

The phenotype of the D1/D2KO mouse, with two exceptions (vide infra) appears largely to be the sum of those of the individual D1KO and D2KO mice from which it was derived, suggesting that in general, the D1 and D2 do not compensate for each other. All the features of the D2KO mouse are present including pituitary resistance to T4 (12), reduced brain T3 content, and increased brain T4 content. However, the alterations in the levels of gene expression were notably greater than those in the D2KO mouse, although they were still not as great as those seen in the hypothyroid mice. Despite this observation, there was no clear evidence of impairment in locomotion, learning, or memory skills.

As in the D1KO, the disposition of TH was altered; whereas in the absence of the D1 the urinary excretion of [125I]iodide by D1KO mice injected with [125I]T4 was greatly reduced (9), when the D2 was also absent, all the radioactivity was excreted in the feces as organic compounds.

Both the D1KO and D2KO mice have a modest elevation in their serum T4 level of approximately 30–50%. Thus, the nearly 2-fold increase in serum T4 level in the D1/D2KO mouse represents an additive increase in this parameter. This increase likely reflects in part an increased thyroidal T4 secretion rate due to the increase TSH level. The finding that D1/D2KO and WT mice are able to clear a bolus of injected T4 from serum to the same degree indicates that T4 clearance in the mutant animal is not delayed. This suggests that either the D3 or biliary/intestinal mechanisms are critical in T4 clearance.

The only synergistic effect evident in the D1/D2KO mouse is the 6-fold increase in serum rT3 compared with only a 2-fold increase in the D1KO animal and no increase in the D2KO mouse. This likely results from a decrease in rT3 clearance resulting from the lack of all 5′D processes as well as increased extrathyroidal production of rT3 by the D3 due to the increased level of T4 substrate. Indeed, the importance of the D3 in the generation of rT3 in both WT and D1/D2KO mice is substantiated by the finding that the serum rT3 level is undetectable in a triple D1/D2/D3KO mouse despite an elevated T4 level (Galton, V. A., Hernandez, A., unpublished observations). In addition, the possibility of enhanced thyroidal secretion of rT3 due to the increased serum TSH level (27,28) cannot be excluded.

These studies provide additional insight into the roles of the D1 and D2 in TH homeostasis. Whereas both enzymes appear to contribute to the serum T3 level under normal circumstances (10), it is apparent that these enzymes are not essential to the maintenance of this parameter as long as the hypothalamic/pituitary/thyroid axis is intact. This finding underscores the importance of the thyroid per se as a source of T3. This is particularly true in the rodent in which 55% of the serum T3 appears to be obtained directly from this organ under normal circumstances (6), with a much greater contribution possible if conditions demand it, such as in iodine deficiency (29), and the D1/D2KO mouse.

Our finding that the D1 and D2 do not compensate for the actions of the other indicates that they have independent roles in TH homeostasis. The role of the D2, whose catalytic activity seems limited almost exclusively to the conversion of T4 to T3, appears well defined; it is clearly important for T3 generation from T4 in brain, pituitary gland, and BAT (12,13,14), and it also contributes some T3 to the serum under both euthyroid and hypothyroid conditions (11,30). In contrast, the role of the D1, with its broad substrate specificity and ability to carry out both 5′D and 5D, is less well understood. Indeed, a complete deficiency of this enzyme, although altering the metabolic and excretion patterns of TH, does not result in any demonstrable morbidity or abnormalities in organ function (9).

We propose that the D1 functions in extrathyroidal tissues principally as a scavenger enzyme to deiodinate inactive (e.g. rT3, sulfated iodothyronines, T2s, and T1s) iodothyronines as well as other TH derivatives [e.g. triiodothyroacetic acid (31)], thus clearing these compounds from the circulation and serving, if necessary, to recycle iodine within the organism. This hypothesis is consistent with the properties of this enzyme (32): our previous findings that substrates other than T4 are used preferentially by the D1 for 5′D (9) and that in the absence of the D1, iodide is lost in the feces in the form of iodinated compounds [vide supra and (9)]. Thus, we anticipate that the D1 may be especially important in iodine deficiency.

The D1 may serve a similar role in the thyroid. Although iodothyronines comprise only a minority of the iodinated residues on thyroglobulin, the majority consisting of mono- and diiodotyrosine, their proportion increases in iodine deficiency along with the proportion of T3, whereas the proportion of T4 declines markedly (33). The thyroid gland contains a dehalogenase (DEHAL1) that deiodinates iodotyrosines (34,35) but not iodothyronines (36) released from thyroglobulin, hence conserving iodotyrosine iodine locally within the gland. Thus, the presence also of a deiodinase with a preference for rT3 and lesser iodothyronines would complement DEHAL1 in preventing thyroidal accumulation and/or secretion of inactive iodoamino acids and also aid in iodine conservation. The observation that D1 activity in the thyroid is markedly increased during iodine deficiency due to the elevated serum TSH level is consistent with this concept.

The levels of T4, T3, and TSH in serum observed in the D1/D2KO mouse are similar to those recently reported by Christoffolete et al. (37) in a D2KO mouse cross-bred with the C3H strain. This latter mouse exhibits a very low level of D1 activity in liver and kidney, whereas in the thyroid gland, it is maintained at 50% of the WT level. It was noted that the serum rT3 level in the D2KO/C3H mutants is not increased, reinforcing the concept that thyroidal D1 may blunt rT3 secretion by metabolizing this compound within the gland.

The degree to which D1 activity contributes to the thyroidal T3 secretion rate remains uncertain. In hyperthyroid states and perhaps iodine deficiency, in which the thyroidal D1 activity is markedly increased, a significant fraction of the secreted T3 appears to be generated via this enzymatic process (38). However, in short-term cultures of TSH-stimulated mouse thyroid glands, propylthiouracil does not impair T3 secretion (28), consistent with our finding here that a D1 deficiency does not compromise thyroidal T3 secretion.

In summary, although the D1 and D2 are not essential for serum T3 homeostasis, they do serve important roles in TH economy, with the D2 critical for T3 production in selected tissues and the D1 poised to play an important role in iodide conservation by serving as a scavenger enzyme in both peripheral tissues and the thyroid. Finally, our studies suggest that patients with a serum TH profile similar to that in the D1/D2KO mouse, namely with elevated TSH, T4, and rT3 levels with no increase or a slight decrease in the T3 level, might harbor mutations in DIO1 or DIO2 genes, or in genes whose products are critical for the synthesis of selenoproteins, as has recently been described (39).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Arturo Hernandez for his helpful suggestions both during the study and with preparation of the manuscript. They also thank Ms. Cheryl Withrow and Mr. George Aldrich for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Public Health Service Grants HD 09020 (to V.A.G.) and DK 54716 (to D.L.S.G.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 5, 2009

For editorial see page 2502

Abbreviations: BAT, Brown adipose tissue; BW, body weight; Cb, cerebellum; CCx, cerebral cortex; 5D, 5-deiodination; 5′D, 5′deiodination; D1, type 1 deiodinase; D2, type 2 deiodinase; D3, type 3 deiodinase; D1KO, D1 deficient; D2KO, D2 deficient; P, neonatal day; TH, thyroid hormone; WT, wild type.

References

- Oppenheimer JH, Koerner D, Schwartz HL, Surks MI 1972 Specific nuclear triidothyronine binding sites in rat liver and kidney. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 35:330–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR 2002 Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev 23:38–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JL, Visser TJ 1986 Biochemistry of deiodination. In: Hennemann G, ed. Thyroid hormone metabolism. New York: Marcel Dekker; 189–229 [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ 1988 Metabolism of thyroid hormones. In: Cooke BA, King RJB, van der Molen HJ, eds. Hormones and their action, part 1. New York: Elsevier Science Publishers; 81–103 [Google Scholar]

- Chopra IL 1996 Nature, source and relative significance of circulating thyroid hormones. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, eds. Werner and Ingbar’s the thyroid. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 111–124 [Google Scholar]

- Chanoine JP, Braverman LE, Farwell AP, Safran M, Alex S, Dubord S, Leonard JL 1993 The thyroid gland is a major source of circulating T3 in the rat. J Clin Invest 91:2709–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MJ, Grieco D, Taylor BA, Maia AL, Kieffer JD, Beamer W, Glover E, Poland A, Larsen PR 1993 Physiological and genetic analysis of inbred mouse strains with a type I iodothyronine 5′ deiodinase deficiency. J Clin Invest 92:1517–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streckfuss F, Hamann I, Schomburg L, Michaelis M, Sapin R, Klein MO, Köhrle J, Schweizer U 2005 Hepatic deiodinase activity is dispensable for the maintenance of normal circulating thyroid hormone levels in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337:739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MJ, Fiering SN, Thai B, Wu SY, St. Germain E, Parlow AF, St. Germain DL, Galton VA 2006 Targeted disruption of the type1 selenodeiodinase gene (Dio1) results in marked changes in thyroid hormone economy in mice. Endocrinology 147:580–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, Chapa F, DiStefano 3rd JJ 1998 Direct measurement of the contributions of type I and type II 5′-deiodinases to whole body steady state 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine production from thyroxine in the rat. Endocrinology 139:4626–4633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia AL, Kim BW, Huang SA, Harney JW, Larsen PR 2005 Type 2 deiodinase is the major source of plasma T3 in euthyroid humans. J Clin Invest 115:2524–2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MJ, Fiering SN, Pallud SE, Parlow AF, St. Germain DL, Galton VA 2001 Targeted disruption of the type 2 selenodeiodinase gene (DIO2) results in a phenotype of pituitary resistance to T4. Mol Endocrinol 15:2137–2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus LA, Carvalho SD, Ribeiro MO, Schneider M, Kim SW, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Bianco AC 2001 The type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is essential for adaptive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 108:1379–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng L, Goodyear RJ, Woods CA, Schneider MJ, Diamond E, Richardson GP, Kelley MW, St. Germain DL, Galton VA, Forrest D 2004 Hearing loss and retarded cochlear development in mice lacking type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:3473–3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton VA, Wood ET, St. Germain EA, Withrow CA, Aldrich G, St. Germain GM, Clark AS, St. Germain DL 2007 Thyroid hormone homeostasis and action in the type 2 deiodinase-deficient brain during development. Endocrinology 148: 3080–3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony A, Adams PM, Stein SA 1993 The effects of congenital hypothyroidism using the hyt/hyt mouse on locomotor activity and learned behavior. Horm Behav 27:418–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi J, St. Germain DL 1992 The cDNA for the type I iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase encodes an enzyme manifesting both high Km and low Km activity. J Biol Chem 267:12539–12544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton VA, Martinez E, Hernandez A, St. Germain EA, Bates JM, St. Germain DL 1999 Pregnant rat uterus expresses high levels of the type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase. J Clin Invest 103:979–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Germain DL, Galton VA 1985 Comparative study of pituitary-thyroid hormone economy in fasting and hypothyroid rats. J Clin Invest 75:679–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roti E, Gnudi A, Braverman LE, Robuschi G, Emanuele R, Bandini P, Benassi L, Pagliani A, Emerson CH 1981 Human cord blood concentrations of thyrotropin, thyroglobulin, and iodothyronines after maternal administration of thyrotropin-releasing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 53:813–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CC, Potter GB 2000 Thyroid hormone action in neural development. Cereb Cortex 10:939–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal J, Guadaño-Ferraz A, Morte B 2003 Perspectives in the study of thyroid hormone action on brain development and function. Thyroid 13:1005–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler D, Burger AG 1984 The deiodination of the iodothyronines and their derivatives in man. Endocr Rev 5:151–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson VJ, Cavalieri RR, Rosenberg LL 1981 Phenolic and non-phenolic ring deiodinase from rat thyroid gland. Endocrinology 108:1257–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H, Inada M, Tanaka K, Mashio Y, Naito K, Nishikawa M, Matsuzuka F, Kuma K, Imura H 1982 Sequential deiodination of thyroxine in human thyroid gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 55:890–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SC, Kubota K, Kuzuya N, Ikeda H, Uchimura H, Nagataki S 1983 Effects of prolonged administration of thyrotrophin on serum concentration, release and synthesis of thyroid hormones in mice. Acta Endocrinol 103:68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegler L, Gillquist J, Lindvall R, Almqvist S, Roos P 1983 Thyroid hormone secretion rates: response to endogenous and exogenous TSH in man during surgery. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 18:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Uchimura H, Mitsuhashi T, Chiu SC, Kuzuya N, Nagataki S 1984 Effects of intrathyroidal metabolism of thyroxine on thyroid hormone secretion: increased degradation of thyroxine in mouse thyroids stimulated chronically with thyrotrophin. Acta Endocrinol 105:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H, Yasuda N, Greer MA, Kutas M, Greer SE 1975 Changes in plasma thyroxine, triiodothyronine, and TSH during adaptation to iodine deficiency in the rat. Endocrinology 97:307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JE, Matthews P 1984 Thyroid hormone metabolism and the source of plasma triiodothyronine in 2-week-old rats: effects of thyroid status. Endocrinology 114:2394–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers M, Heusdens FA, Bonthuis F, Visser TJ 1989 Metabolism of triiodothyroacetic acid (TA3) in rat liver. II. Deiodination and conjugation of TA3 by rat hepatocytes and in rats in vivo. Endocrinology 125:433–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Berry MJ, Horst C, Thoma R, Goglia F, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Visser TJ 1994 Activation and inactivation of thyroid hormone by type I iodothyronine deiodinase. FEBS Let 344:143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesco G, Taurog A, Larsen PR 1976 Variations in the response of the thyroid gland of the rat to different low-iodine diets: correlation with the iodine content of the diet. Endocrinology 99:270–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbury JB 1960 Deiodination of the iodinated amino acids. Ann NY Acad Sci 86:417–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnidehou S, Caillou B, Talbot M, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Noël-Hudson MS, Morand S, Agnangji D, Sezan A, Courtin F, Virion A, Dupuy C 2004 Iodotyrosine dehalogenase 1 (DEHAL1) is a transmembrane protein involved in the recycling of iodide close to the thyroglobulin iodination site. FASEB J 18:1574–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solís-S JC, Villalobos P, Orozco A, Valverde-R C 2004 Comparative kinetic characterization of rat thyroid iodotyrosine dehalogenase and iodothyronine deiodinase type 1. J Endocrinol 181:385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffolete MA, Arrojo e Drigo R, Gazoni F, Tente SM, Goncalves V, Amorim BS, Larsen PR, Bianco AC, Zavacki AM 2007 Mice with impaired extrathyroidal thyroxine to 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine conversion maintain normal serum 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine concentrations. Endocrinology 148:954–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurberg P, Vestergaard H, Nielsen S, Christensen SE, Seefeldt T, Helleberg K, Pedersen KM 2007 Sources of circulating 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine in hyperthyroidism estimated after blocking of type 1 and type 2 iodothyronine deiodinases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2149–2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu AM, Liao XH, Abdullah MS, Lado-Abeal J, Majed FA, Moeller LC, Boran G, Schomburg L, Weiss RE, Refetoff S 2005 Mutations in SECISBP2 result in abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism. Nat Genet 37:1247–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]