Abstract

Precise control of pulsatile GnRH and LH release is imperative to ovarian cyclicity but is vulnerable to environmental perturbations, like stress. In sheep, a sustained (29 h) increase in plasma cortisol to a level observed during stress profoundly reduces GnRH pulse frequency in ovariectomized ewes treated with ovarian steroids, whereas shorter infusion (6 h) is ineffective in the absence of ovarian hormones. This study first determined whether the ovarian steroid milieu or duration of exposure is the relevant factor in determining whether cortisol reduces LH pulse frequency. Prolonged (29 h) cortisol infusion did not lower LH pulse frequency in ovariectomized ewes deprived of ovarian hormones, but it did so in ovariectomized ewes treated with estradiol and progesterone to create an artificial estrous cycle, implicating ovarian steroids as the critical factor. Importantly, this effect of cortisol was more pronounced after the simulated preovulatory estradiol rise of the artificial follicular phase. The second experiment examined which component of the ovarian steroid milieu enables cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency in the artificial follicular phase: prior exposure to progesterone in the luteal phase, low early follicular phase estradiol levels, or the preovulatory estradiol rise. Basal estradiol enabled cortisol to decrease LH pulse frequency, but the response was potentiated by the estradiol rise. These findings lead to the conclusion that ovarian steroids, particularly estradiol, enable cortisol to inhibit LH pulse frequency. Moreover, the results provide new insight into the means by which gonadal steroids, and possibly reproductive status, modulate neuroendocrine responses to stress.

Presence of estradiol is obligatory for stress-like levels of cortisol to decrease luteinizing hormone pulse frequency in the follicular phase of the ovine estrous cycle.

It is well documented that stress inhibits pulsatile secretion of gonadotropic hormones and simultaneously activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (1,2,3,4,5). Recent studies in ovariectomized sheep indicate that psychosocial stress, such as isolation combined with restraint, blindfolding and the sound of a barking dog, reduces the amplitude of LH pulses at two levels of reproductive neuroendocrine activity: the hypothalamus to lower the amplitude of GnRH pulses secreted into pituitary portal blood (6) and the anterior pituitary to lower responsiveness to GnRH (7). The suppressive effect of this stress upon the pituitary can be prevented by blocking the action of cortisol (7), and it can be recapitulated in nonstressed ewes by mimicking the rise in plasma cortisol induced by the stress (8,9,10). Thus, the rise in plasma cortisol that accompanies psychosocial stress is both necessary and sufficient for the suppression of pituitary responsiveness to GnRH and the consequent lowering of LH pulse amplitude.

Although the effect of cortisol to suppress pituitary responsiveness to GnRH and lower LH pulse amplitude is established, we repeatedly observed that an increment in plasma cortisol similar to that induced by psychosocial stress does not reduce GnRH or LH pulse frequency in ovariectomized ewes devoid of gonadal steroids or, at most, has a minimal effect (9,10,11). Cortisol, however, does decrease the frequency of both GnRH and LH pulses in ovary-intact ewes during the follicular phase of the estrous cycle (12,13) and in ovariectomized ewes treated with estradiol and progesterone to simulate their secretory patterns during the follicular phase (13). Those observations suggest an interaction exists between adrenal and gonadal steroids, such that ovarian hormones enable cortisol to decrease GnRH and thus LH pulse frequency. However, the study demonstrating cortisol profoundly reduces GnRH pulse frequency in the presence of ovarian steroids employed a sustained 29-h infusion of cortisol (13), whereas the studies indicating cortisol does not do so in the absence of ovarian hormones used a shorter 6-h infusion (9,10,11). The difference in efficacy of cortisol to reduce pulse frequency, therefore, could have been due to different durations of cortisol infusion rather than ovarian steroid status.

The initial goal of this study was to distinguish between duration of exposure vs. ovarian steroid milieu as the relevant factor in determining whether cortisol reduces LH pulse frequency. Our results implicated ovarian steroids as the critical factor. We thus conducted another experiment to identify which component of the follicular phase steroid environment enables cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency: prior exposure to progesterone in the luteal phase, the mere presence of estradiol, or the preovulatory increase in estradiol secretion.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted in successive breeding seasons (October to December 2005 and 2006) on adult Suffolk ewes maintained under standard husbandry conditions at the Sheep Research Facility near Ann Arbor, MI. Ewes were fed hay and alfalfa pellets and had free access to water and mineral licks. Ovariectomy was performed aseptically under general anesthesia. All procedures were approved by the Committee for the Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan.

Experiment 1: does extended duration of cortisol exposure or presence of ovarian steroids enable cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency?

This study compared responses to a prolonged (29 h) cortisol infusion in two groups of 12 ewes: long-term ovariectomized ewes deprived of ovarian hormones for 8 months and ewes ovariectomized and immediately treated with estradiol and progesterone to simulate secretory patterns of these hormones during the estrous cycle (see Fig. 1A for details). This model has been used extensively to investigate hormonal interrelationships of the ovine estrous cycle (14,15,16,17,18); the period after progesterone withdrawal is referred to as the artificial follicular phase. One week before sampling, ewes were moved to rooms where photoperiod simulated that of the outdoors. Three days later, two indwelling jugular catheters were inserted, one for sampling blood and one for infusing cortisol or vehicle via battery-powered pumps (Autosyringe, model AS2BH; Hooksett, NH) carried in backpacks. Six ewes of each group received vehicle (saline), and six others received a 29-h infusion of cortisol (0.20 mg/kg·h, Solu-Cortef, hydrocortisone sodium succinate, aqueous solution; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI). A pilot study determined this dose elevated plasma cortisol to about 80 ng/ml, within the upper range of concentrations observed in this laboratory during psychosocial stress and the lower range of values induced by immune/inflammatory stress (7,19). The onset of cortisol infusion (defined as h 0) was 1 h before progesterone withdrawal (removal of progesterone implants) to initiate the artificial follicular phase. Jugular blood for LH pulse analysis was sampled every 5 min from 13–17 and 25–29 h, referred to as the early and late sampling periods, respectively. The early period ended just before the simulated preovulatory estradiol rise of the artificial follicular phase, and the late period began 8 h after onset of the estradiol rise (see Fig. 1A). Cortisol was assayed hourly during each sampling period. Due to technical difficulties with infusions, two cortisol-treated ovariectomized ewes and one cortisol-treated artificial follicular phase ewe were excluded from the analysis.

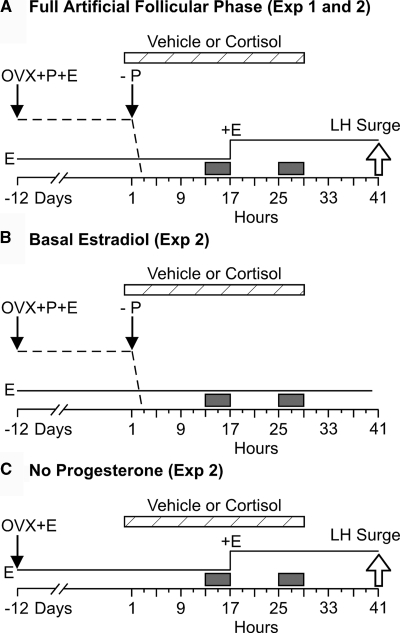

Figure 1.

Schematic description of the animal model and designs of experiment (Exp) 1 and 2. A, Artificial follicular phase model used in experiment 1 (full artificial follicular phase group in experiment 2). Ewes were ovariectomized (OVX) in the early luteal phase of the estrous cycle (d −12) and immediately treated with two intravaginal progesterone (P)-releasing devices (controlled internal drug release; DEC International NZ/Ltd, Hamilton, New Zealand) and a single 1-cm estradiol (E) implant sc, which maintains luteal phase plasma concentrations of estradiol (1–2 pg/ml) and progesterone (2–4 ng/ml) (15,52). After 12 d, the P devices were removed to simulate corpus luteum regression (−P, arrow) and four 3-cm estradiol implants were inserted sc 16 h later to simulate the follicular phase rise in estradiol secretion (+E). Preovulatory-like surges of GnRH and LH (open arrow, LH surge) typically begin about 24 h after onset of the estradiol rise to 6–8 pg/ml (13,15,18). B, Basal estradiol group of experiment 2, which differed from the full artificial follicular phase group in that the simulated preovulatory estradiol rise was omitted. C, No progesterone group of experiment 2, which differed from the full artificial follicular phase in that progesterone was not administered. Plasma progesterone and estradiol patterns are schematically depicted by the dashed and solid lines, respectively. Time in hours is relative to onset (0 h) of cortisol or vehicle infusion (cross-hatched horizontal bars). Frequent sampling periods are indicated by solid boxes.

Experiment 2: what hormonal component of the follicular phase enables cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency?

Experiment 1 indicated cortisol reduced LH pulse frequency only in the artificial follicular phase group, and this effect was most prominent after the estradiol rise. This suggested the preovulatory estradiol rise is especially critical in allowing cortisol to decrease frequency. To test this hypothesis, specific hormonal components of the artificial follicular phase model were selectively eliminated to test the importance of three aspects of the ovarian hormone milieu: prior presence of progesterone in the simulated luteal phase, low level of estradiol typical of the early follicular phase, and preovulatory estradiol rise. There were three groups of 12 ewes: 1) full artificial follicular phase—fall in progesterone, basal estradiol (1–2 pg/ml) followed by estradiol rise to 6–8 pg/ml (Fig. 1A); 2) basal estradiol—fall in progesterone, basal estradiol but no estradiol rise (Fig. 1B); and 3) no progesterone—basal estradiol followed by estradiol rise but no prior progesterone (Fig. 1C). Plasma estradiol and progesterone concentrations are well characterized in this model (14,15,16,17,18) and were not monitored here. Six ewes in each group received cortisol, and six others received vehicle. Other procedures and sampling times were as in experiment 1, except vehicle or cortisol (0.24 mg/kg · h) was infused via remote peristaltic pump rather than backpack pumps and the no progesterone group did not receive progesterone at ovariectomy. One vehicle-treated animal in the full artificial follicular phase group began to have an LH surge during the late sampling period and was excluded from the analysis.

Hormone assays

LH was assayed in duplicate aliquots (10–200 μl) of plasma using a modification (20) of a previously described RIA (21,22); values are expressed in terms of NIH LH-S12. Mean intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 4.6 and 10.2%, respectively, and assay sensitivity averaged 0.55 ng/ml (29 assays). Total plasma cortisol was assayed in duplicate 50-μl aliquots of unextracted plasma using the Coat-A-Count cortisol assay kit (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Los Angeles, CA), validated for use in sheep (19). Mean intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 6.3 and 8.4%, respectively, and assay sensitivity averaged 0.58 ng/ml (17 assays).

Data analysis

LH pulses were identified by the Cluster pulse detection algorithm (23). As in our previous studies (12,16,24), cluster sizes for peaks and nadirs were defined as 2, and the t statistic to identify a significant increase or decrease was 2.6. LH pulse amplitude was the difference between a peak and its preceding nadir. Frequency was defined as number of pulses per 4 h. Before statistical analysis, hormone concentration was log transformed and frequency was square-root transformed to normalize variability across a range of values. Frequency and mean pulse amplitude were obtained in every ewe for each sampling period. These values were subjected to repeated-measures ANOVA with one repeated measure (sampling period) and two grouping factors (group and treatment) to identify effects of group (ovarian steroid status), treatment (vehicle vs. cortisol), and period (early vs. late) as well as four types of interactions: 1) group × treatment to identify whether cortisol effects depend on ovarian steroid status, 2) treatment × period to determine whether cortisol effects differ between the early and late sampling periods, 3) group × period to determine whether values during the early and late sampling periods depend on ovarian steroid status, and 4) group × treatment × period to determine whether cortisol effects differ between early and late sampling periods and among groups. If a significant group × treatment × period interaction was identified, post hoc analysis was performed to identify treatment and period effects within each group. Post hoc analysis consisted of successively excluding data from one group and conducting repeated-measures ANOVA on the remaining groups. In experiment 2, the repeated-measures ANOVA revealed cortisol lowered pulse frequency in all three groups (full artificial follicular phase, basal estradiol, and no progesterone groups), and this response appeared to be particularly evident after the estradiol rise. To analyze this further, Fisher’s exact probability test was conducted to determine whether the proportion of ewes in which frequency dropped markedly (i.e. by two or more pulses/4 h) between the early and late sampling periods was greater in ewes that received the estradiol rise than in those that did not. Cortisol values were examined by two-way ANOVA to test for group differences. Significance was set at the 5% level.

Results

Experiment 1: does extended duration of cortisol exposure or presence of ovarian steroids enable cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency?

During vehicle treatment, plasma cortisol concentrations remained low and stable in both long-term ovariectomized and artificial follicular phase ewes (8.0 ± 0.9 and 8.8 ± 1.3 ng/ml, respectively, mean ± sem). These concentrations are similar to those we observe in nonstressed ewes (7,8,9,12,25). Values during cortisol infusion increased to 83.2 ± 5.0 ng/ml in long-term ovariectomized ewes and 68.0 ± 4.2 ng/ml in artificial follicular phase ewes; these concentrations are within the range observed in this laboratory during stress (7,19). Values during cortisol infusion were greater in untreated ovariectomized ewes than in artificial follicular phase ewes (P < 0.02).

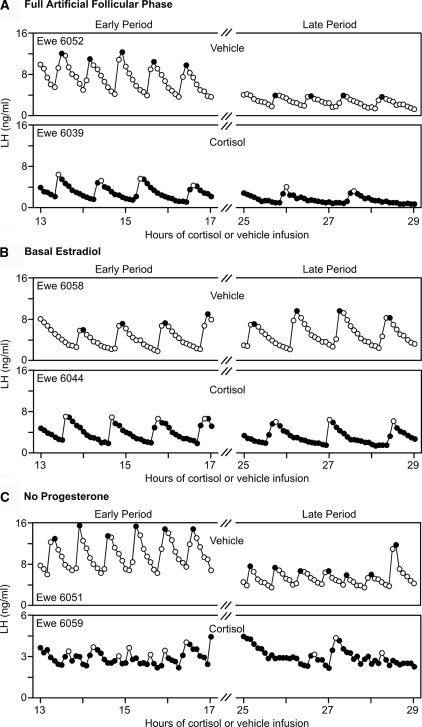

Representative LH patterns in a cortisol- and vehicle-treated ewe of each group during the early and late sampling periods are illustrated in Fig. 2; composite results and statistical analyses are summarized in Table 1. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed cortisol reduced LH pulse frequency (treatment effect), and this effect varied according to both group and sampling period (i.e. significant treatment × group × period interaction). Specifically, cortisol significantly lowered frequency in artificial follicular phase ewes but failed to do so in ovariectomized ewes not treated with ovarian steroids. Furthermore, this effect was more pronounced in the late sampling period, i.e. after the estradiol rise (treatment × period interaction).

Figure 2.

A, Example LH profiles from vehicle-treated (top) and cortisol-treated (bottom) ovariectomized ewes in which ovarian steroid hormones were not replaced. B, LH profiles from vehicle-treated (top) and cortisol-treated (bottom) ovariectomized ewes in which ovarian steroids were replaced to mimic the follicular phase of the estrous cycle. For both A and B, the early (13–17 h) and late (25–29 h) sampling periods are shown on the left and right, respectively. Peaks of pulses are depicted with contrasting open or filled circles.

Table 1.

Effects of cortisol on LH pulses in the presence and absence of ovarian steroids (experiment 1)

| Mean LH pulse frequency (pulses/4 h)a

|

Mean LH pulse amplitude (ng/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early period | Late period | Early period | Late period | |

| Ovariectomized | ||||

| Vehicle | 6.67 ± 0.33 | 6.33 ± 0.21 | 9.88 ± 2.81 | 17.87 ± 5.90 |

| Cortisol | 6.75 ± 0.48 | 7.25 ± 0.48 | 4.73 ± 1.75e | 5.38 ± 1.84 |

| Artificial follicular phase | ||||

| Vehicle | 5.17 ± 0.31 | 5.17 ± 0.48 | 8.95 ± 2.74 | 3.24 ± 1.29d |

| Cortisol | 4.60 ± 0.51b | 2.20 ± 0.66b,c | 5.94 ± 0.90e | 3.02 ± 1.25d |

Values are mean ± sem. Early period is 13–17 h, and late period is 25–29 h after onset of cortisol or vehicle infusion.

Treatment × group × period interaction as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.02).

Treatment effect as determined by post hoc analysis: values lower in cortisol vs. vehicle-treated animals (P < 0.02).

Treatment × period interaction as determined by post hoc analysis: values lower in late period than early period of cortisol-treated animals (P < 0.05).

Group × period interaction as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA: values lower in late period, artificial follicular phase (P < 0.001).

Treatment effect as determined by ANOVA on the early period only: values lower in cortisol vs. vehicle-treated animals (P = 0.05).

With respect to amplitude, LH pulses were smaller in the late compared with the early sampling period in artificial follicular ewes but not in ovariectomized ewes devoid of ovarian steroids (i.e. group × period interaction, Table 1). However, repeated-measures ANOVA did not reveal an overall effect of cortisol (no treatment effect) and no group × treatment × period interaction. Because estradiol itself is known to reduce GnRH and LH pulse amplitude in the ewe (16,26), a separate ANOVA was conducted on amplitude in the early period only (i.e. before the estradiol rise). This analysis revealed cortisol lowered pulse amplitude relative to values in vehicle-treated controls (treatment effect), and this response did not vary significantly between ovariectomized and artificial follicular phase ewes (no group × treatment interaction).

Experiment 2: what hormonal component of the follicular phase enables cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency?

Plasma cortisol concentrations remained low during vehicle infusion and did not differ among the three groups (overall mean ± sem, 9.6 ± 1.0 ng/ml). During cortisol infusion, values increased to about 80 ng/ml and did not vary among groups (full artificial follicular phase 83.5 ± 5.5 ng/ml; no estradiol rise 80.1 ± 3.6 ng/ml; no progesterone 82.6 ± 4.3 ng/ml).

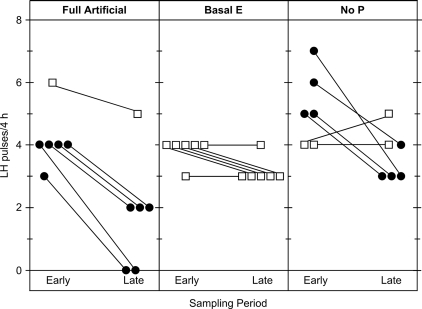

LH patterns in a representative cortisol- and vehicle-treated ewe of each group are shown in Fig. 3; composite results are presented in Table 2. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed an overall effect of cortisol to lower pulse frequency (treatment effect). This effect increased over time; i.e. cortisol reduced frequency more in the late compared with the early sampling period (treatment × period interaction). However, the effect of cortisol did not differ according to group (no significant treatment × group interaction), and the effect over time did not vary with group (no significant group × treatment × period interaction). Nevertheless, the proportion of ewes in which frequency decreased markedly over time (lowered by two or more pulses from the early to late sampling period) was greater if ewes received the estradiol rise between the two sampling periods (nine of 12 ewes in the full artificial follicular phase and no progesterone groups combined vs. zero of six ewes in the basal estradiol group; P < 0.01 by Fisher’s exact probability test) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Example LH profiles from vehicle-treated (top) and cortisol-treated (bottom) ewes from full artificial follicular phase group (A), basal estradiol group (B), and no progesterone group (C). For A–C, the early (13–17 h) and late (25–29 h) sampling periods are shown on the left and right, respectively. Peaks of pulses are depicted with contrasting open or filled circles.

Table 2.

Effects of cortisol on LH pulses in the presence and absence of ovarian steroids (experiment 2)

| Mean LH pulse frequency (pulses/4h)a

|

Mean LH pulse amplitude (ng/ml)c,e

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early period | Late period | Early period | Late periodd | |

| Full artificial follicular phase | ||||

| Vehicle | 3.80 ± 0.37 | 3.20 ± 0.58 | 6.95 ± 0.35 | 3.33 ± 0.65 |

| Cortisol | 4.17 ± 0.40 | 1.83 ± 0.75b | 4.94 ± 1.34 | 2.25 ± 0.94 |

| Basal estradiol | ||||

| Vehicle | 4.50 ± 0.34 | 4.17 ± 0.40 | 5.07 ± 1.40 | 6.61 ± 2.11 |

| Cortisol | 3.83 ± 0.17 | 3.17 ± 0.17b | 4.14 ± 0.48 | 4.10 ± 0.53 |

| No progesterone | ||||

| Vehicle | 5.67 ± 0.42 | 6.17 ± 0.60 | 11.96 ± 1.27 | 4.17 ± 1.30 |

| Cortisol | 5.17 ± 0.48 | 3.67 ± 0.33b | 4.19 ± 0.99 | 2.65 ± 0.69 |

Values are mean ± sem, frequency (pulses/4 h), amplitude (ng/ml), Early Period is 13–17 h, and Late Period is 25–29 h after onset of cortisol or vehicle infusion.

Treatment effect as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA: values lower in cortisol vs. vehicle-treated animals (P < 0.01).

Treatment × period interaction as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA: values lower in late period in cortisol-treated animals (P < 0.01).

Treatment effect as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA: values lower in cortisol vs. vehicle-treated animals (P < 0.02).

Period effect: values lower in late period vs. early period (P < 0.001).

Group × treatment × period interaction (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Change in LH pulse frequency between the early (13–17 h) and late (25–29 h) sampling periods in individual cortisol-treated ewes of each experimental group. The late period was after the estradiol (E) rise in the full artificial follicular phase and no progesterone (P) groups. Frequencies in individual ewes are depicted by points (solid or open) connected by a line. Solid points depict ewes in which frequency decreased by two or more pulses between the early and late periods; open points depict ewes in which frequency did not decrease to this extent.

Cortisol lowered LH pulse amplitude (treatment effect); this effect did not differ among groups (no significant group × treatment interaction). Furthermore, amplitude was lower in the late compared with the early sampling period (period effect). This period effect varied by group (group × treatment × period interaction); it was evident only in ewes receiving the estradiol rise (Table 2).

Discussion

The initial goal of this study was to distinguish between duration of exposure to cortisol vs. ovarian steroid milieu as the relevant factor in determining whether cortisol reduces LH pulse frequency. This was based on our prior findings that a sustained (29 h) increase in plasma cortisol to a level observed during stress profoundly reduced GnRH pulse frequency in ovariectomized ewes treated with ovarian steroids to simulate the estrous cycle (13), whereas a shorter infusion (6 h) failed to do so in the absence of ovarian hormones (9,11). Using LH as a marker of GnRH pulse frequency in experiment 1, we determined that duration alone cannot account for these differing results. The 29-h cortisol infusion did not lower LH pulse frequency in ovariectomized ewes deprived of ovarian hormones, but the same treatment did reduce frequency if ovariectomized ewes received ovarian steroids to mimic the follicular phase of the estrous cycle. The present results reinforce the previous conclusion that ovarian hormones enable cortisol to act centrally to lower GnRH pulse frequency (13), and they fit nicely with recent findings that cortisol decreases GnRH pulse frequency in the follicular phase of the natural estrous cycle (13).

Given this conclusion, an important next step was to identify which hormonal component of the follicular phase enables cortisol to reduce GnRH pulse frequency. Based on the finding in experiment 1 that cortisol was especially effective in lowering frequency after estradiol increased (i.e. in the late sampling period), we tested the hypothesis that the estradiol rise is the essential component, again using LH as a marker for GnRH pulse frequency. Although global statistical analysis of experiment 2 (repeated-measures ANOVA) revealed the presence of estradiol is necessary for cortisol to decrease frequency, it did not confirm the estradiol rise is obligatory. Nonetheless, when the results were analyzed in terms of severity of the effect, the proportion of ewes in which frequency was reduced by two or more pulses between the early and late sampling periods was greater if ewes had received the estradiol rise between the two periods. Thus, although not necessary for cortisol to reduce LH pulse frequency, the estradiol rise likely plays an enhancing role. In a physiological context, this could intensify the effect of cortisol in the mid-late follicular phase when estradiol is nearing its peak.

A sensitizing influence of estradiol to factors that inhibit reproductive neuroendocrine activity is not unique to cortisol and not limited to effects on the hypothalamus. For example, at the pituitary level, estradiol amplifies cortisol-induced suppression of responsiveness to GnRH (27). Also, estradiol sensitizes the GnRH neurosecretory system to progesterone negative feedback, which lowers GnRH pulse frequency in luteal phase ewes (28). This effect of estradiol most likely reflects enhanced expression of the progesterone receptor (PR) (29,30,31). Of interest, estrogen receptor α (ERα), PR, and the type II glucocorticoid receptor (GR) are coexpressed in the same neurons in the preoptic area and arcuate nucleus of sheep (32). Progesterone increased the number of type II GR-immunoreactive cells in these areas, and estradiol reduced this response (33). Although this seems paradoxical to the permissive action of estradiol observed in the present work, it does suggest an interaction exists between ovarian steroids and responsiveness to the glucocorticoids. Nevertheless, the type II GR, PR and ERα are not expressed in GnRH neurons (33,34,35). Thus, cortisol and progesterone probably act indirectly, possibly via a common inhibitory interneuronal system to lower GnRH pulse frequency.

Strong evidence indicates the interneuronal system through which progesterone inhibits GnRH pulse frequency in ewes involves endogenous opioid peptides (36,37,38). In particular, dynorphin and β-endorphin neurons in the arcuate nucleus contain both ERα and PR (39,40), and they mediate the negative feedback action of progesterone on GnRH pulse frequency (37). Endogenous opioid peptides also appear to mediate reproductive suppression during certain types of stress (41,42,43), although it is not known whether they mediate the action of cortisol on GnRH secretion. We recently gathered preliminary evidence that dynorphin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the ewe contain type II GR and that a stress-like elevation in plasma cortisol increases the number of immunocytochemically identifiable dynorphin-expressing cells in the arcuate nucleus (44). Further work is needed to determine whether this population of opioidergic neurons provides a substrate for interaction between cortisol and estradiol and serves as a final common pathway by which both cortisol and progesterone reduce GnRH pulse frequency.

Although the present work strongly implicates a role for estradiol in allowing cortisol to reduce LH and thus GnRH pulse frequency, three caveats should be mentioned. First, some earlier reports suggest cortisol can reduce LH pulse frequency in ovariectomized ewes not treated with ovarian steroids. The response, however, was inconsistent (11), small in magnitude (∼10% reduction) (10,11), or evident only when plasma cortisol was elevated to a very high level (45), considerably higher than that employed here and that observed during stress. Because cortisol reduces LH pulse amplitude in a dose-dependent fashion (10,11,45), high-dose cortisol might actually lower LH pulse frequency by a pituitary rather than a hypothalamic effect, i.e. by inhibiting pituitary responsiveness to the point that some GnRH pulses fail to elicit detectable LH responses. The second caveat relates to this point. Our use of LH as a marker of GnRH pulsatility leaves open the possibility that the frequency effects observed here reflect an action of cortisol on the pituitary rather than the hypothalamus. Although possible, this is unlikely given our recent finding that cortisol reduces GnRH pulse frequency in both the natural and artificial follicular phase, as determined by direct measurement of GnRH in pituitary portal blood (13). A third caveat pertains to our conclusion regarding duration of cortisol exposure. Our experiments do not exclude a role for duration. Experiment 2 did identify a period effect in which frequency was lowered to a greater extent in the late compared with the early sampling window. This period effect, however, was probably due to an interaction between cortisol and the estradiol rise, rather than duration of cortisol in itself, because it was not observed if cortisol was combined with basal estradiol. Also related to duration, a 6-h cortisol infusion in the natural follicular phase was previously found to be ineffective in lowering GnRH and LH pulse frequency, whereas a longer infusion was effective (13), indicating a threshold duration of more than 6 h must be achieved. This could provide a buffer to prevent estrous cycle disruption in response to a single brief elevation in cortisol during the estrous cycle.

It is also important to consider the physiological relevance of the present work to stress-induced suppression of reproductive neuroendocrine function. Clearly, the plasma concentration of cortisol achieved by infusion was similar to levels induced by stress. Duration of the cortisol increment, however, exceeded that during most stresses, with the exception of severe immune/inflammatory stress (18,46) and pathological conditions such as Cushing’s disease in which cortisol is chronically elevated and reproductive function is compromised (47,48). With regard to physiological relevance of the interaction between cortisol and estradiol, we recently observed psychosocial stress lowered GnRH pulse amplitude, but not frequency, in ovariectomized ewes, and this was independent of cortisol action (6). Importantly, those ewes were not treated with estradiol, and it would be interesting to determine whether estradiol influences this response. Earlier studies in sheep revealed gonadal steroids influence effects of stress on LH pulse frequency and amplitude (49). Clearly, further work is needed to assess the extent to which cortisol contributes to stress-induced inhibition of pulsatile GnRH secretion and whether cortisol acts in concert with other stress-induced mechanisms and estradiol to lower GnRH pulse frequency.

Finally, the hormonal manipulations of the present study influenced amplitude as well as frequency of LH pulses. Cortisol lowered amplitude regardless of whether ewes received the full or a partial follicular phase complement of ovarian steroids in experiment 2, and it reduced amplitude during the early period in both ovariectomized ewes not treated with ovarian steroids and in artificial follicular phase ewes before the estradiol rise in experiment 1. The ability of cortisol to reduce LH pulse amplitude in ovariectomized ewes by suppressing pituitary responsiveness to GnRH has been observed repeatedly (8,9,25,27). Of interest, amplitude of LH pulses in artificial follicular phase ewes was lower after than before the estradiol rise in both experiments, and this held in both cortisol- and vehicle-treated ewes. This result can be explained by the rise in estradiol rather than cortisol because it did not occur in the basal estradiol group of experiment 2, and estradiol, like cortisol, is known to suppress pituitary responsiveness to GnRH and thus LH pulse amplitude (16,26). Therefore, estradiol has both complementary (amplitude) and facilitatory (frequency) actions on the suppressive effects of cortisol on pulsatile LH secretion.

Collectively, the foregoing observations indicate the presence of ovarian steroids, particularly estradiol, enables cortisol to decrease LH pulse frequency in the ewe. This influence of ovarian steroids may help to explain why reproductive responses to stress vary with reproductive state of an individual (50,51). An intriguing hypothesis emerges whereby estradiol serves as a gatekeeper to the action of both cortisol and progesterone in decreasing GnRH pulse frequency.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Doug Doop and Gary McCalla for the exceptional animal care they provided, to Alison Cooper for her assistance in conducting the experiments, to Drs. Gordon D. Niswender and Leo E. Reichert Jr. for supplying RIA reagents, and to Morton Brown for consultation on the data analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD30773, T32-07048, and T32-08322.

Present address for A.E.O.: Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195.

Present address for K.M.B.: Department of Reproductive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093.

Preliminary reports have appeared in the 39th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Reproduction, 2006 [Biol Reprod 73(Suppl 1):19], the 2006 Society for Neuroscience Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner (Abstract 776.3), and the 2007 Society for Neuroscience Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner (Abstract 556.3).

Disclosure Summary: The authors of this manuscript have nothing to declare.

First Published Online January 29, 2009

Abbreviations: ERα, Estrogen receptor α; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

References

- Breen KM, Karsch FJ 2006 New insights regarding glucocorticoids, stress and gonadotropin suppression. Front Neuroendocrinol 27:233–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook AJ, Turner AI, Clarke IJ 2000 Effects of stress on reproduction in non-rodent mammals: the role of glucocorticoids and sex differences. Rev Reprod 5:105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson H, Smith RF 2000 What is stress, and how does it affect reproduction? Anim Reprod Sci 60–61:743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C, Rivest S 1991 Effect of stress on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis: peripheral and central mechanisms. Biol Reprod 45:523–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferin M 1993 Neuropeptides, the stress response, and the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis in the female rhesus monkey. Ann NY Acad Sci 697:106–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmaker ER, Breen KM, Oakley AE, Tilbrook AJ, Karsch FJ 2009 Psychosocial stress inhibits amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses independent of cortisol action on the type II glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology 150:762–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Oakley AE, Pytiak AV, Tilbrook AJ, Wagenmaker ER, Karsch FJ 2007 Does cortisol acting via the type II glucocorticoid receptor mediate suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in response to psychosocial stress? Endocrinology 148:1882–1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Stackpole CA, Clarke IJ, Pytiak AV, Tilbrook AJ, Wagenmaker ER, Young EA, Karsch FJ 2004 Does the type II glucocorticoid receptor mediate cortisol-induced suppression in pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin-releasing hormone? Endocrinology 145:2739–2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Karsch FJ 2004 Does cortisol inhibit pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion at the hypothalamic or pituitary level? Endocrinology 145:692–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus N, Breen KM, Barrell GK, Billings HJ, Brown M, Young EA, Karsch FJ 2002 Does cortisol mediate endotoxin-induced inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion? Endocrinology 143:3748–3758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Karsch FJ 2006 Does season alter responsiveness of the reproductive neuroendocrine axis to the suppressive actions of cortisol in ovariectomized ewes? Biol Reprod 74:41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Billings HJ, Wagenmaker ER, Wessinger EW, Karsch FJ 2005 Endocrine basis for disruptive effects of cortisol on preovulatory events. Endocrinology 146:2107–2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley AE, Breen KM, Clarke IJ, Karsch FJ, Wagenmaker ER, Tilbrook AJ 2009 Cortisol reduces gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency in follicular phase ewes: influence of ovarian steroids. Endocrinology 150:341–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Legan SJ, Ryan KD, Foster DL, Karsch FJ 1981 Importance of variations in behavioural and feedback actions of oestradiol to the control of seasonal breeding in the ewe. J Endocrinol 89:229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moenter SM, Caraty A, Karsch FJ 1990 The estradiol-induced surge of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ewe. Endocrinology 127:1375–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NP, Dahl GE, Glover BH, Karsch FJ 1994 Central regulation of pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion by estradiol during the period leading up to the preovulatory GnRH surge in the ewe. Endocrinology 134:1806–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NP, Dahl GE, Padmanabhan V, Thrun LA, Karsch FJ 1997 Estradiol requirements for induction and maintenance of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge: implications for neuroendocrine processing of the estradiol signal. Endocrinology 138:5408–5414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia DF, Beaver AB, Harris TG, Tanhehco E, Viguié C, Karsch FJ 1999 Endotoxin disrupts the estradiol-induced luteinizing hormone surge: interference with estradiol signal reading, not surge release. Endocrinology 140:2471–2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia DF, Bowen JM, Krasa HB, Thrun LA, Viguié C, Karsch FJ 1997 Endotoxin inhibits the reproductive neuroendocrine axis while stimulating adrenal steroids: a simultaneous view from hypophyseal portal and peripheral blood. Endocrinology 138:4273–4281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauger RL, Karsch FJ, Foster DL 1977 A new concept for control of the estrous cycle of the ewe based on the temporal relationships between luteinizing hormone, estradiol and progesterone in peripheral serum and evidence that progesterone inhibits tonic LH secretion. Endocrinology 101:807–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Midgley Jr AR, Reichert Jr LE 1968 Radioimmunologic studies with murine, ovine and porcine luteinizing hormone. In: Rosenborg E, ed. Gonadotropins. Los Altos, CA: Geron-X; 299–306 [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Reichert Jr LE, Midgley Jr AR, Nalbandov AV 1969 Radioimmunoassay for bovine and ovine luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology 84:1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML 1986 Cluster analysis: a simple, versatile, and robust algorithm for endocrine pulse detection. Am J Physiol 250:E486–E493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moenter SM, Brand RM, Midgley AR, Karsch FJ 1992 Dynamics of gonadotropin-releasing hormone release during a pulse. Endocrinology 130:503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Davis TL, Doro LC, Nett TM, Oakley AE, Padmanabhan V, Rispoli LA, Wagenmaker ER, Karsch FJ 2008 Insight into the neuroendocrine site and cellular mechanism by which cortisol suppresses pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology 149:767–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Karsch FJ 1980 Pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone: differential suppression by ovarian steroids. Endocrinology 107:1286–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce BN, Stackpole CA, Breen KM, Clarke IJ, Karsch FJ, Rivalland ET, Turner AI, Caddy DJ, Wagenmaker ER, Oakley AE, Tilbrook AJ 2009 Estradiol enables cortisol to act directly upon the pituitary to suppress pituitary responsiveness to GnRH in sheep. Neuroendocrinology 89:86–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Bittman EL, Foster DL, Karsch FJ 1981 The endocrine basis of the synergistic suppression of luteinizing hormone by estradiol and progesterone. Endocrinology 109:1414–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CJ, Pereira AM, Tilbrook AJ, Rawson JA, Clarke IJ 2001 Changes in preoptic and hypothalamic levels of progesterone receptor mRNA across the oestrous cycle of the ewe. J Neuroendocrinol 13:401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RE, Wu-Peng XS, Pfaff DW 2002 Regulation and expression of progesterone receptor mRNA isoforms A and B in the male and female rat hypothalamus and pituitary following oestrogen treatment. J Neuroendocrinol 14:175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo M, Kilen SM, Nho SJ, Schwartz NB 2000 Progesterone receptor A and B messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the anterior pituitary of rats are regulated by estrogen. Biol Reprod 62:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufourny L, Skinner DC 2002 Progesterone receptor, estrogen receptor α, and the type II glucocorticoid receptor are coexpressed in the same neurons of the ovine preoptic area and arcuate nucleus: a triple immunolabeling study. Biol Reprod 67:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufourny L, Skinner DC 2002 Type II glucocorticoid receptors in the ovine hypothalamus: distribution, influence of estrogen and absence of co-localization with GnRH. Brain Res 946:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner DC, Caraty A, Allingham R 2001 Unmasking the progesterone receptor in the preoptic area and hypothalamus of the ewe: no colocalization with gonadotropin-releasing neurons. Endocrinology 142:573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Karsch FJ 1993 Do gonadotropin-releasing hormone, tyrosine hydroxylase-, and β-endorphin-immunoreactive neurons contain estrogen receptors? A double-label immunocytochemical study in the Suffolk ewe. Endocrinology 133:887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL 1994 Neuroendocrine control of the ovine estrous cycle. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, eds. The physiology of reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 659–709 [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Anderson GM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Connors JM, Fitzgerald ME, Lehman MN 2004 Evidence that dynorphin plays a major role in mediating progesterone negative feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Endocrinology 145:2959–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL 1996 Neural systems mediating the negative feedback actions of estradiol and progesterone in the ewe. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 56:727–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foradori CD, Coolen LM, Fitzgerald ME, Skinner DC, Goodman RL, Lehman MN 2002 Colocalization of progesterone receptors in parvicellular dynorphin neurons of the ovine preoptic area and hypothalamus. Endocrinology 143:4366–4374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufourny L, Caraty A, Clarke IJ, Robinson JE, Skinner DC 2005 Progesterone-receptive β-endorphin and dynorphin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus project to regions of high gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron density in the ovine preoptic area. Neuroendocrinology 81:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraglia F, Vale W, Rivier C 1986 Opioids act centrally to modulate stress-induced decrease in luteinizing hormone in the rat. Endocrinology 119:2445–2450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska D, Mateusiak K, Przekop F 1999 Changes in extracellular LHRH and β-endorphin-like immunoreactivity in the nucleus infundibularis-median eminence of anestrous ewes under stress condition. J Neural Transm 106:265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagampang FR, Cates PS, Sandhu S, Strutton PH, McGarvey C, Coen CW, O'Byrne KT 1997 Hypoglycaemia-induced inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in female rats: role of oestradiol, endogenous opioids and the adrenal medulla. J Neuroendocrinol 9:867–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley AE 2008 Central inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on reproductive function: permissive role of estradiol. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI [Google Scholar]

- Stackpole CA, Clarke IJ, Breen KM, Turner AI, Karsch FJ, Tilbrook AJ 2006 Sex difference in the suppressive effect of cortisol on pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone in sheep. Endocrinology 147:5921–5931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia DF, Krasa HB, Padmanabhan V, Viguié C, Karsch FJ 2000 Endocrine alterations that underlie endotoxin-induced disruption of the follicular phase in ewes. Biol Reprod 62:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado-Abeal J, Rodriguez-Arnao J, Newell-Price JD, Perry LA, Grossman AB, Besser GM, Trainer PJ 1998 Menstrual abnormalities in women with Cushing’s disease are correlated with hypercortisolemia rather than raised circulating androgen levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3083–3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuerda C, Estrada J, Marazuela M, Vicente A, Astigarraga B, Bernabeu I, Diez S, Salto L 1991 Anterior pituitary function in Cushing’s syndrome: study of 36 patients. Endocrinol Jpn 38:559–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook AJ, Canny BJ, Serapiglia MD, Ambrose TJ, Clarke IJ 1999 Suppression of the secretion of luteinizing hormone due to isolation/restraint stress in gonadectomised rams and ewes is influenced by sex steroids. J Endocrinol 160:469–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajantie E, Phillips DI 2006 The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31:151–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, Hoffman CL, Fulks R, Gerald MS 2008 Plasma cortisol responses to stress in lactating and nonlactating female rhesus macaques. Horm Behav 53:170–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cleeff J, Karsch FJ, Padmanabhan V 1998 Characterization of endocrine events during the periestrous period in sheep after estrous synchronization with controlled internal drug release (CIDR) device. Domest Anim Endocrinol 15:23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]