Abstract

Psychological stress can impact on visceral function with pathological consequences, although the mechanisms underlying this are poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that social stress produces marked changes in bladder structure and function. Male rats were subjected to repeated (7 days) social defeat stress using the resident-intruder model. Measurement of the voiding pattern indicated that social stress produced urinary retention. Consistent with this, bladder size was increased in rats exposed to social stress. Moreover, this was negatively correlated to the latency to assume a subordinate posture, implying an association between passive behavior and bladder dysfunction. In vivo cystometry revealed distinct changes in urodynamic function in rats exposed to social stress, including increased bladder capacity, micturition volume, intermicturition interval, and the presence of non-micturition-related contractions, resembling overactive bladder. In contrast to social stress, repeated restraint (7 days) did not affect voiding, bladder weight, or urodynamics. The stress-related neuropeptide corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is present in spinal projections of Barrington's nucleus that regulate the micturition reflex and has an inhibitory influence in this pathway. Social stress, but not restraint, increased the number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus. Additionally, social stress increased CRF mRNA in Barrington's nucleus. Together, the results imply that social stress-induced CRF upregulation in Barrington's nucleus neurons results in urinary retention and, eventually, bladder dysfunction, perhaps as a visceral component of a behavioral coping response. This mechanism may underlie dysfunctional voiding in children and/or contribute to the development of stress-induced bladder disorders in adulthood.

Keywords: Barrington's nucleus, social defeat, micturition, cystometry, resident intruder

chronic or repeated stress has numerous adverse psychological and physiological consequences (33). The mechanisms by which stress produces adverse effects have been studied in rodents using a variety of stressors. However, many of these stressors lack ethological validity (i.e., footshock). One stressor that is more ethologically relevant and is currently being used to model stress-related pathology involves social defeat (44). This model, in which a rodent is forced into submission by a larger male conspecific, has been used by several groups to examine behavioral and endocrine consequences of social stress (3, 17, 24, 39, 44). A visceral effect of social stress that is often reported, but has not been systematically investigated, is urinary retention that can develop into bladder hypertrophy and even nephropathy due to reflux (10, 16, 29). The neural processes through which social stimuli can sufficiently impact bladder function to produce structural changes remain unknown.

Neural circuits linking the brain and bladder that are sensitive to stress likely mediate the impact of social stress on the bladder. One such circuit involves projections from Barrington's nucleus in the pons to preganglionic parasympathetic neurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord (28). These projections mediate the efferent limb of the micturition reflex by regulating bladder contraction in response to distention (8). Barrington's nucleus neurons contain the stress-related neuropeptide, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). In addition to its role in mediating endocrine and behavioral aspects of the stress response (1, 45), CRF is a neuromodulator in the micturition pathway from Barrington's nucleus to the spinal cord where it has an inhibitory influence on micturition (35). Thus this is a potential mechanism that can be recruited by social stress to produce urinary retention.

To better understand how social stress can produce bladder pathology, the present study characterized the effect of repeated social defeat stress on bladder structure and function by measuring bladder weight, voiding patterns, and urodynamics using in vivo cystometry. Because CRF is prominent in circuits linking the brain and bladder, CRF expression in Barrington's nucleus was also quantified. To determine whether the effects of social stress generalized to other stressors, the effects of repeated restraint stress on bladder function and CRF expression in Barrington's nucleus were compared with those produced by social stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male Long-Evans retired breeders (650–850 g) served as residents (Charles River), and all other subjects were male Sprague-Dawley rats (275–300 g). Rats were singly housed in a 12:12-h light-dark, climate controlled room with food and water freely available. All studies were approved by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Use of Laboratory Animals.

Social defeat (resident-intruder) paradigm and restraint.

The social defeat paradigm (4) was originally modified from the resident-intruder paradigm developed by Miczek (34). Intruder rats were placed in the cage of a novel, Long-Evans resident for 30 min on seven consecutive days. The endpoint of defeat was met when the intruder assumed a supine position in response to the resident's aggressive behaviors. At this point, a wire mesh enclosure was placed in the cage to prevent physical contact between the resident and intruder but allowing visual, auditory, and olfactory contact to be maintained for the remainder of the 30-min session. Controls were placed behind a wire partition in a novel cage for 30 min daily. Rats were returned to their home cage after each session. A separate cohort of rats was exposed to restraint (30 min) in a Plexiglas tube for seven consecutive days. The control rats in the restraint study, unlike controls for defeated rats, were left in the home cage and not handled during the 7-day paradigm.

Quantification of voiding pattern.

Voiding pattern measurements were conducted 24 h before the first stress or control manipulation and 24 h after the final manipulation. Subjects were placed individually in a cage with the floor lined with filter paper for 90 min. Urine spots on the filter paper were allowed to dry, illuminated with ultraviolet light, and photographed. The number of urine spots was quantified using Image J by an individual blind to the treatment groups. In addition, magnification of the photographs allowed for easy identification of overlapping but distinct spots.

Quantification of urodynamics.

Bladder catheters were surgically implanted from 5 to 24 h after the last voiding pattern experiments. Urodynamic function was recorded using cystometry in the unanesthetized state 48 h after surgery as previously described (22). Sterile saline was continuously infused (100 μl/min) through the bladder catheter while urodynamic endpoints were recorded on-line for 1 h using cystometry equipment and software (Medical Associates, St. Albans, VT). At least three consecutive voiding events were used to calculate the urodynamic parameters of bladder pressure, bladder capacity (volume of infused saline in a micturition cycle), micturition volume, micturition threshold, resting pressure, peak micturition pressure, non-micturition-related contractions, and intermicturition interval. Nonmicturition contractions were analyzed by Cystometry Analysis Software (SOF-522) from Catamount R&D (St. Albans, VT). The program considers only bladder contractions >5 mmHg and 3.5 s duration and not associated with urine expulsion as non-micturition-related contractions. These were counted in a 10-min interval. Residual volume was calculated as the difference between the infused volume and the voided volume averaged over three voiding events. Rats were killed 24 h after the cystometry session. Bladders from rats used in cystometry experiments were not included in bladder weight comparisons. Likewise, brain tissue used for quantification of CRF mRNA or protein was not obtained from rats used in cystometry experiments.

Quantification of CRF-immunoreactive neurons.

To determine whether social stress or restraint produced alterations in the expression of CRF protein, the number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus was quantified. Rats were decapitated 24 h after the final defeat, restraint, or matched control manipulations and brains were removed and frozen. Coronal serial sections (14 μm thick) were cut on slides (Fisherbrand ProbeOn Plus; Fisher Scientific). Sections containing Barrington's nucleus were processed to visualize CRF and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity, as previously described (47). Because TH-immunoreactivity reveals different levels of the nearby norepinephrine-containing nucleus, locus coeruleus, this was used as an anatomical landmark to match the rostrocaudal levels of sections used for quantification. Sections were postfixed by incubating slides in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h followed by rinses. Sections were incubated with a cocktail of rabbit anti-CRF (C-70, 1:2,000, Wylie Vale, Salk Institute) and mouse anti-TH (1:5,000) for 48 h at 4°C. The specificity of the anti-CRF antibody has been previously characterized by ourselves and others (5, 41, 49). These groups showed an absence of staining when sections were incubated with the antibody that has been preabsorbed with the antigenic peptide and when the primary antiserum was omitted. Figure 1 of Supplementary data verifies the absence of CRF-immunoreactive staining in Barrington's nucleus sections that have been incubated with the preabsorbed antibody or in the absence of the primary antibody (Supplemental data for this article may be found on the American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology website.). Using dot blots, the concentration dependence of the reaction was verified as well as lack of cross-reactivity with products of melanin-concentrating hormone precursor (49). Finally, the antibody solution contains 1 mg/ml alpha-MSH to assure no cross-reactivity with this peptide. Following rinses, the sections were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody and fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (1:200; Jackson Laboratories) for 90 min. Sections from stressed rats and their matched controls were processed at the same time using identical solutions. Immunoreactivity was visualized using a Leica fluorescent microscope, and the exposure duration was maintained at a constant value for the comparison of all sections at the same time. Images were captured using a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera and Open Lab software (Improvision). CRF-immunoreactive cells within the core of Barrington's nucleus were counted and averaged from two nonserial sections per rat by an individual blinded to the treatment condition. For CRF-expressing cell quantification, images were magnified and inverted in grayscale, such that cells showed up in black and background was white. This allowed for unambiguous distinction between staining within a cell and the background. The mean number of CRF neurons in Barrington's nucleus for a particular group was determined by taking the mean of these averages for individual subjects within an experimental group.

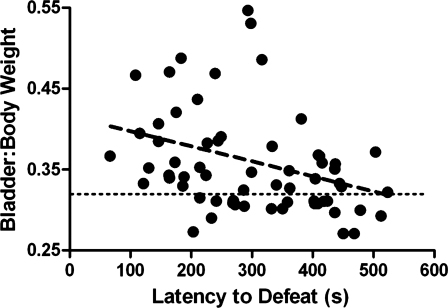

Fig. 1.

Social stress produced bladder hypertrophy that is negatively correlated to latency to assume a subordinate posture. The abscissa indicates the latency to defeat, and the ordinate indicates the bladder-to-body weight ratio. The horizontal line indicates the mean bladder weight in control rats. Each point represents an individual subject exposed to social stress. There was a significant negative correlation between these endpoints, suggesting that bladder hypertrophy is associated with passive behavior (r = −0.32, P = 0.015).

Quantification of CRF mRNA.

Because social stress altered the number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus, tissue from social stressed and control rats were also processed for CRF mRNA analysis. Sections adjacent to those used for immunohistochemistry were processed to quantify CRF mRNA as previously described (50). Sections were postfixed by incubating in 10% formalin before hybridization with an antisense riboprobe to CRF mRNA (Dr. Audrey F. Seasholtz, University of Michigan) and coated with Kodak NTB2 liquid autoradiographic emulsion (7-day exposure at 4°C). Following emulsion development, the tissue was lightly stained with cresyl violet. Brightfield microscopy was used in combination with Open Lab software to count cells within Barrington's nucleus. For quantification, brightfield images were magnified to identify cresyl violet-stained cells within the nucleus containing silver grains more than two to four times background. The average number of CRF-expressing cells from two sections representing the core of Barrington's nucleus were quantified and averaged for each rat by an individual who was blind to the treatment condition.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Unpaired Student's t-tests were used to identify significant differences in absolute bladder weight or bladder-to-body weight ratios between defeated rats and their controls, as well as restrained rats and matched controls. In addition, all cystometry parameters were analyzed using unpaired Student's t-tests to determine differences between defeated or restrained rats and their matched controls. Differences in CRF protein and mRNA-expressing cell count between stressed animals and matched controls were also analyzed using unpaired Student's t-tests. Voiding pattern experiments were quantified using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferoni post hoc tests. Data were analyzed by evaluating treatment condition (stress vs. matched control) by day (day 0 vs. day 8) in defeated rats and matched controls as well as restrained rats and matched controls.

RESULTS

Repeated social defeat, but not restraint, results in bladder hypertrophy.

As an initial indication of stress-related bladder dysfunction, bladder weight was measured with respect to body weight and compared between rats exposed to the stressors and their matched controls. Rats subjected to social defeat had greater bladder-to-body weight ratios (0.37 ± 0.01, n = 67) than matched controls (0.32 ± 0.01, n = 46; P = 0.0006). Moreover, the bladder-to-body weight ratio was negatively correlated with the latency to assume the defeat posture, suggesting a link between bladder dysfunction and submissive behavior (Fig. 1). Social stress did not decrease body weight although weight gain during the 7 days was attenuated for the intruders compared with controls [47 ± 3 vs. 35 ± 2 g; t(26) = 3.8; P = 0.0008]. Importantly, because body weight alone was not correlated with defeat latency (r2 = 0.03, P = 0.15), the negative correlation between bladder-to-body weight ratio and defeat latency is unrelated to differences in body weight. In addition, the mean absolute bladder weight was also increased in social stressed rats above control values (121.1 ± 2.9 vs. 112.2 ± 2.5 mg, respectively; P = 0.033). In contrast to social stress, repeated restraint had no effect on bladder-to-body weight ratio, which was 0.29 ± 0.01 (n = 19) in restraint rats and 0.30 ± 0.01 (n = 14) in matched controls (P = 0.67), suggesting that the bladder hypertrophy produced by social stress does not generalize to all stressors.

Repeated social defeat, but not restraint, alters bladder function.

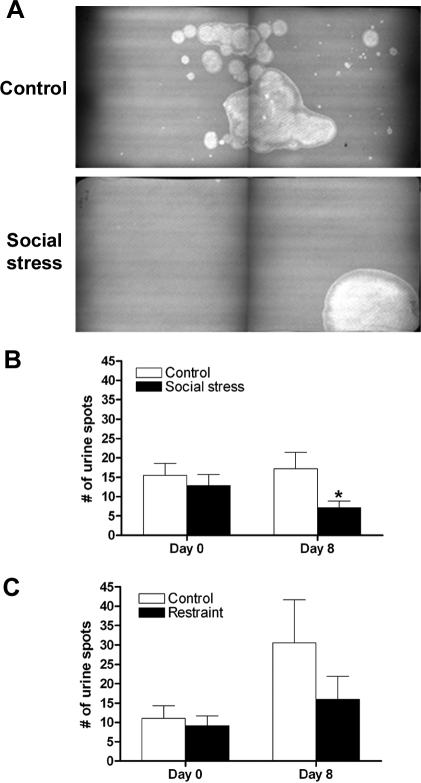

Quantification of the voiding pattern after 7 days of social stress was consistent with urinary retention in social stressed rats compared with controls. Before any manipulation (day 0), both groups urinated ubiquitously throughout the cage as indicated by a comparable number of voiding spots (Fig. 2B). However, after 7 days of social defeat or control manipulation there was a significant stress effect [F(1,46)=4.4; P = 0.04] whereby defeated rats had fewer urination spots than control animals on day 8 (Fig. 2, A and B). Furthermore, control animals continued to void throughout the cage, similar to day 0, whereas defeated subjects urinated in the corners of the cage (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, repeated restraint stress had no effect on the number of voiding spots compared with controls [F(1,24) = 1.03; P = 0.32] (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Social stress, but not restraint, resulted in urinary retention. A: representative voiding patterns from a control and social stressed rat 24 h after the seventh and final manipulation. Each image is a montage of two halves of the voiding pattern paper that was cut in half to accommodate the size of the ultraviolet light box. B: bars indicate the mean number of urine spots for controls (n = 9) or social stressed (n = 15) rats on day 0 or 24 h after the final manipulation (day 8). C: bars indicate the mean number of urine spots for controls (n = 6) or restraint stressed (n = 8) rats on day 0 or 24 h after the final manipulation (day 8). *P < 0.05, Bonferroni post hoc vs. matched controls.

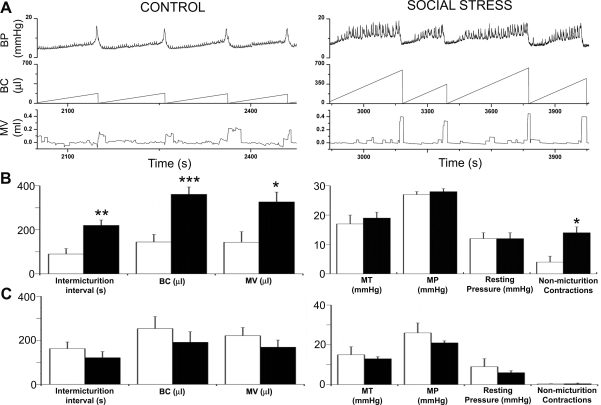

Cystometry records revealed marked changes in urodynamic function produced by social stress that in some ways resembled those produced by partial bladder outlet obstruction, a prevalent bladder disorder (38). Representative cystometrograms illustrate numerous non-micturition-related contractions indicative of overactive detrusor in the rat exposed to social stress that were not present in controls (Fig. 3A). Additionally, the urodynamic profile of the social stressed rat was characterized by fewer micturition events occurring during an equivalent period of time, and larger bladder capacity and micturition volume compared with the control rat (Fig. 3A). Figure 3A shows that the same number of micturition events (4) occurs over a much longer time for the social stressed rat (1,200 s) compared with the control rat (420 s). Quantification of the mean urodynamic parameters revealed a significant increase in the intermicturition interval in social stressed subjects compared with matched controls, consistent with urinary retention (Fig. 3B). As a result, both bladder capacity and micturition volume were greater in social stressed rats (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the number of spontaneous nonmicturition contractions was also greater in defeated subjects (Fig. 3, A and B). One-third of the rats exposed to social stress (5 of 15) displayed dribbling incontinence that was absent in unstressed controls. Finally, there was a trend for greater residual urine (202 ± 86 vs. 44 ± 25 μl, P = 0.07, unpaired t-test) in social stressed rats. Micturition threshold, resting pressure, and peak micturition pressure were comparable between groups (Fig. 3B). Notably, there was no difference in any of these urodynamic parameters in rats exposed to repeated restraint stress compared with their matched controls (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Social stress, but not restraint, altered the urodynamic profile. A: representative cystometrograms from a control and defeated rat. Top to bottom, traces of bladder pressure, volume of saline infused (i.e., bladder capacity), and micturition volume. Also indicated is the finding that the same number of micturition events occur over a much longer time for the social stressed rat (1,200 s) compared with the control rat (420 s). Therefore, the time scales on the abscissas differ between the two examples to illustrate 4 voiding events for each animal. B: bars are the mean values of control (open bars, n = 9) and social stressed (filled bars, n = 15) rats for intermicturition interval, bladder capacity (BC), micturition volume (MV), micturition threshold (MT), micturition pressure (MP), resting pressure, and nonmicturition contractions. C: bars are the mean values of control (open bars, n = 6) and restraint stressed (filled bars, n = 8) rats for the same urodynamic parameters as shown in B. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 unpaired Student's t-test.

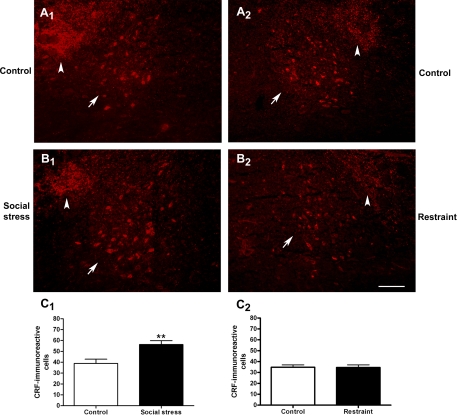

Social defeat stress increases CRF-immunoreactive- and CRF mRNA-expressing neurons in Barrington's nucleus.

Given evidence for an inhibitory influence of CRF in the pontine micturition circuit (35), the effect of social stress on CRF expression in Barrington's nucleus was examined. Figure 4, A and B, shows representative fluorescent photomicrographs of CRF immunolabeling in the core of Barrington's nucleus. Quantification revealed that social stress increased the number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus (Fig. 4C1). In contrast, restraint stress had no effect on CRF immunoreactivity in Barrington's nucleus (Fig. 4C2). Notably, the number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus in controls matched for social stress (38.9 ± 3.9, n = 9), controls matched for restraint stress (34.9 ± 5.4, n = 7), and restraint stress (34.6 ± 6.6, n = 8) rats were nearly identical. This experiment was repeated in another cohort of social stressed rats and matched controls at another time, and a similar finding that the mean (±SE) number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus was greater in social stressed rats (34.0 ± 2.4; n = 17) than controls (23.2 ± 3.6; n = 13) was repeated (P = 0.02, unpaired Student's t-test).

Fig. 4.

Social stress, but not restraint, increased the number of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus. A: fluorescent photomicrographs of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus of representative control rats from the defeat (A1) and restraint (A2) study. B: fluorescent photomicrographs of CRF-immunoreactive neurons of a social stressed (B1) and restrained (B2) rat 24 h after the 7th manipulation. Photomicrographs were grouped, and contrast and brightness were equally adjusted using Adobe Photoshop. The arrows point to the cluster of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus. The arrowheads point to a CRF-immunoreactive terminal field dorsolateral to Barrington's nucleus that derives from cell bodies in the central nucleus of the amygdala (40, 48). Top is dorsal in all photomicrographs. In A1 and B1, medial is to the right. In A2 and B2, medial is to the left. The calibration bar represents 100 μm. C1: bars represent the mean number of CRF-immunoreactive cells in Barrington's nucleus for controls (n = 9) and social stressed (n = 12) rats. C2: bars represent the mean number of CRF-immunoreactive cells in Barrington's nucleus for controls (n = 7) and restraint stressed (n = 8) rats. **P < 0.01, Student's unpaired t-test.

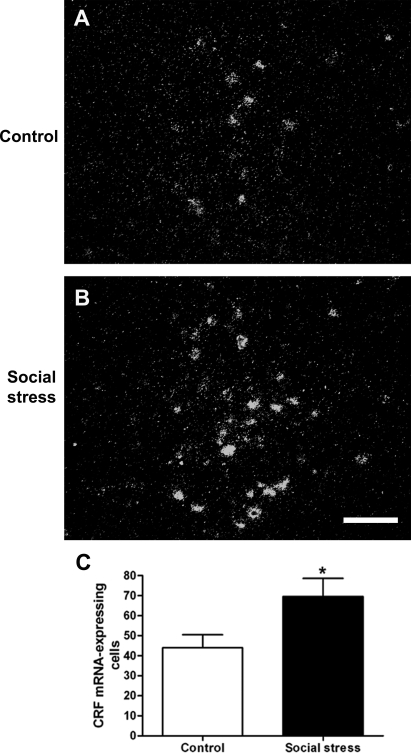

To determine whether effects of social stress to increase the number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons in Barrington's nucleus were the result of increased gene transcription, CRF mRNA was quantified using in situ hybridization. Figure 5, A and B, shows representative darkfield photomicrographs of CRF mRNA expression in Barrington's nucleus of control and social stressed rats. Quantification revealed that social stress increased the number of CRF mRNA-expressing cells within Barrington's nucleus (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Social stress upregulated CRF mRNA expression in Barrington's nucleus. A and B: darkfield photomicrographs showing hybridization signal for CRF mRNA in Barrington's nucleus of a representative control (A) and social stressed (B) rat 24 h after the 7th manipulation. Photomicrographs were grouped, and contrast and brightness was equally adjusted using Adobe Photoshop. Calibration bar represents 100 μm. C: bars represent the mean number of CRF mRNA-expressing cells in Barrington's nucleus in control (n = 8) and social stressed (n = 11) rats. *P < 0.01, Student's unpaired t-test.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that the social stress of the resident-intruder model produced urinary retention and bladder hypertrophy, consistent with other social stress models (10, 16, 19, 29). This is the first study to systematically characterize the urodynamic changes induced by social stress and to provide evidence for a putative neural mechanism. Cystometry revealed overactive detrusor and pathology similar to that produced by partial bladder outlet obstruction (42). However, unlike partial bladder obstruction, micturition pressure was not elevated, suggesting that the stress-related urinary retention resulted from a decreased drive to the bladder rather than increased outflow resistance. Because CRF has an inhibitory influence in Barrington's nucleus spinal projections that regulate the micturition reflex (35), CRF upregulation in Barrington's nucleus by social stress is a putative mechanism for urinary retention. This was further supported by the findings that a nonsocial stressor, restraint stress, neither upregulated CRF protein in Barrington's nucleus nor produced bladder dysfunction. Differences between social and restraint stress on bladder urodynamics could not be attributed to differences in the magnitude of stress habituation, since this is comparable between the two stressors (4, 20). CRF upregulation in Barrington's nucleus and the associated urinary retention may be a visceral component of an adaptive passive coping strategy that is specific to social stress. However, if maintained, it can result in pathological alterations in bladder structure and function. This process may be involved in dysfunctional voiding in children that is characterized by voiding postponement or may contribute to bladder disorders in adulthood.

Relation to previous studies.

Previous studies that have focused on social stress or subordination in rodents report evidence of urinary retention (10, 29). Social subordination in rodents was also reported to produce bladder hypertrophy, a response to long-term urine retention (16, 29). Even a mild social stress model that did not involve aggressive encounters but was based on competition for a preferred food, resulted in greater bladder weight in subordinate rats (19). A recent report in mice has further demonstrated that increases in bladder weight induced by social stress are associated with changes in signaling molecules that have been linked to hypertrophy produced by partial bladder obstruction (54). Nonetheless, a systematic characterization of social stress-induced bladder dysfunction has been lacking, and the question of how a social stimulus could produce bladder pathology has not been previously addressed.

Bladder dysfunction produced by social stress.

The urodynamic profile associated with repeated social stress resembled overactive detrusor and shared characteristics with the pathology seen with partial bladder obstruction. These characteristics include increased bladder capacity, micturition volume, non-micturition-related contractions, and dribbling incontinence (30). An important distinction between the urodynamic profile associated with social stress and that associated with partial obstruction is the absence of increased micturition pressure in the social stress model. This indicates that, in contrast to partial obstruction, which results in increased resistance at the bladder neck, the effects produced by social stress most likely result from decreased central drive to the bladder during the micturition reflex, i.e., decreased parasympathetic tone. Nonetheless, in the absence of direct measurements of urethral tone, an additional effect on the urethral outlet cannot be completely ruled out. The finding that micturition threshold was unaffected suggests that afferent input from the bladder to the brain is intact. Alterations in sympathetic tone do not explain the urodynamic profile produced by social stress because sympathetic activation increases micturition threshold, an effect not observed with social stress (9). Interestingly, with stress models characterized by increased sympathetic tone, such as the spontaneously hypertensive rat (36) or models using cold stress (6), micturition volume, bladder capacity, and intermicturition interval, are all decreased, and these effects are sensitive to α-adrenergic antagonists. This profile is in complete contrast to the effects reported here with social stress. Finally, nonvoiding contractions have been suggested to result from increased spinal regulation of the micturition reflex, an effect indicative of decreased central regulation (43, 52). Thus the urodynamic profile associated with social stress best fits one that would be predicted by decreased central excitatory drive to the bladder during the micturition reflex.

The abnormal urodynamic pattern produced by social stress was observed 3–4 days after the last exposure to stress, suggestive of an enduring effect. Previous studies in mice demonstrated that three exposures to social defeat resulted in inhibition of voiding (as determined by voiding pattern) that persists for 5 wk after the last stress (29). Whether bladder hypertrophy and abnormal urodynamics following social stress in the rat resident-intruder model endures for weeks after the stress or whether it is reversible is a direction of future studies.

Another compelling question is whether this effect occurs in females. The resident-intruder model used in the present study is not a consistently effective stressor in females. Rather, social instability or isolation may better model social stress and potential urodynamic dysfunction in females (15).

CRF in Barrington's nucleus as an underlying mechanism for stress-related bladder dysfunction.

Excitatory input to the bladder during micturition arises from the sacral parasympathetic preganglionic neurons that give rise to the pelvic nerves (8). These neurons are regulated by Barrington's nucleus neurons in the pons that terminate in the parasympathetic preganglionic column and use excitatory amino acid neurotransmission to drive the parasympathetic preganglionic neurons (31, 32, 53). CRF, a stress-related neuropeptide, is prominent in Barrington's nucleus spinal projections and is therefore a potential mediator of stress effects on micturition (51). CRF has an inhibitory influence in this pontine-spinal pathway. For example, bladder contractions elicited by chemical stimulation of Barrington's nucleus are increased by intrathecal microinjection of a CRF antagonist, and intrathecal microinjection of CRF decreases bladder contractions elicited by Barrington's nucleus activation (35). Given evidence for the inhibitory function of CRF within this pathway, CRF upregulation in Barrington's nucleus neurons produced by social stress can account for the associated urinary retention and its enduring consequences on bladder structure and function.

It should be noted that CRF can impact on urination at sites other than the pontine micturition circuit because, in addition to this pathway, it is present in bladder urothelium and at sensory levels of the spinal cord (25, 26). Cystometry studies of the effects of CRF agonists and antagonists on bladder urodynamics have reported equivocal results. A study comparing effects in female Wistar-Kyoto rats with spontaneously hypertensive rats demonstrated that systemic or intrathecal administration of CRF increased urinary frequency and decreased micturition threshold and volume in Wistar-Kyoto rats only (23). Another cystometry study using male Sprague-Dawley rats showed that intrathecal CRF decreased micturition frequency and increased bladder capacity and micturition volume, and these effects were dependent on the state of arousal, occurring only in the awake state (22). These discrepant results may be attributed to differences in the sex and strain of experimental subjects as well as the state of arousal during which CRF effects are measured. These studies underscore the importance of these determinants on the effects of CRF-related agents when administered to the whole animal. Additionally, in these studies, CRF could be exerting its effect at multiple sites. The comparison of bladder contraction elicited by direct stimulation of Barrington's nucleus neurons before and after intrathecal administration of CRF antagonists was the only study to directly examine the role of CRF in this specific pathway and revealed an inhibitory influence of CRF that may serve to balance the excitatory drive to preganglionic parasympathetic neurons (35).

Clinical relevance.

The present findings provide a neurobiological mechanism for the clinical association between social stress and bladder dysfunction. Dysfunctional voiding remains the most common presentation to pediatric urologists (13). Voiding postponement is one form of dysfunctional voiding that can be sufficiently severe as to result in reflux (18). The lack of an anatomical pathology and a positive response to psychological treatments suggest a potential psychogenic basis for the disorder and trauma or abuse during critical times in development have been implicated (2, 12). Consistent with this, children with voiding postponement have a less-balanced family environment and more psychiatric comorbidity compared with children with other types of voiding dysfunction (27). The impact of childhood social stress on bladder function can extend into adulthood, and childhood sexual or physical abuse are associated with urinary disorders characterized by retention in adults (7, 37). Adult traumatic social events (e.g., loss of a loved one, broken marriage) have also been reported to produce urinary retention (14). Our results suggest that targeting CRF may be a rational approach for the development of drugs to treat these disorders.

Perspectives and Significance

Here we show that a social stimulus can profoundly affect the structure and function of viscera. The correlation between subordinate behavior and the visceral response implies that urinary retention in subordinate animals is a visceral component of a passive behavioral repertoire that is engaged in response to social threats. Although transient urinary retention during social stress is acutely adaptive, repeated exposure to the stimulus maintains this visceral response and results in pathological changes in bladder structure and function. One brain region that is poised to coordinate these behavioral and visceral responses is the periaqueductal gray, a region involved in determining active vs. passive coping style (21) that is also a major afferent to Barrington's nucleus (46). Recent findings that social stress in cichlids cause CRF-mediated bile retention and gall bladder hypertrophy suggest that this passive behavioral-visceral repertoire and its underlying substrates are phylogenetically conserved (11). The conservation of this response in humans can contribute to voiding dysfunction and bladder disorders in susceptible individuals. Future studies designed to identify the neural mechanisms by which social stimuli impact on the viscera will advance our understanding of how social experiences shape physical health.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-069963, DK-052620, T32MH-14654, and MH-067651 to S. Bhatnagar.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hayley Walker, Thelma Bethea, Sandra Luz, Vikram Iyer, and Kile McFadden for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44: 525–557, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer SB Special considerations of the overactive bladder in children. Urology 60: 43–49, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatnagar S, Vining C. Facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to novel stress following repeated social stress using the resident/intruder paradigm. Horm Behav 43: 158–165, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatnagar S, Vining C, Iyer V, Kinni V. Changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function, body temperature, body weight and food intake with repeated social stress exposure in rats. J Neuroendocrinol 18: 13–24, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cha CI, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor in olivocerebellar climbing-fiber system of monkey (Saimiri sciureus and Macaca fascicularis): parasagittal and regional organization visualized by immunohistochemistry. J Neurosci 8: 4121–4137, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Ishizuka O, Imamura T, Aizawa N, Igawa Y, Nishizawa O, Andersson KE. Role of alpha(1)-adrenergic receptors in detrusor overactivity induced by cold stress in conscious rats. Neurourol Urodyn doi: 10.1002/nau.20630. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Davila GW, Bernier F, Franco J, Kopka SL. Bladder dysfunction in sexual abuse survivors. J Urol 170: 476–479, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Groat WC, Booth AM, Yoshimura N. Neurophysiology of micturition and its modification in animal models of human disease. In: The Autonomic Nervous System, edited by Maggi CA. London: Harwood, 1993, p. 227–290.

- 9.de Groat WC, Yoshiyama M, Ramage AG, Yamamoto T, Somogyi GT. Modulation of voiding and storage reflexes by activation of alpha1-adrenoceptors. Eur Urol 36, Suppl 1: 68–73, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desjardins C, Maruniak JA, Bronson FH. Social rank in house mice: differentiation revealed by ultraviolet visualization of urinary marking patterns. Science 182: 939–941, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earley RL, Blumer LS, Grober MS. The gall of subordination: changes in gall bladder function associated with social stress. Proc Biol Sci 271: 7–13, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellsworth PI, Merguerian PA, Copening ME. Sexual abuse: another causative factor in dysfunctional voiding. J Urol 153: 773–776, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman AS, Bauer SB. Diagnosis and management of dysfunctional voiding. Curr Opin Pediatr 18: 139–147, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenster H, Patterson B. Urinary retention in sexually abused women. Can J Urol 2: 185–188, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haller J, Fuchs E, Halasz J, Makara GB. Defeat is a major stressor in males while social instability is stressful mainly in females: towards the development of a social stress model in female rats. Brain Res Bull 50: 33–39, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry JP, Meehan WP, Stephens PM. Role of subordination in nephritis of socially stressed mice. Contr Nephrol 30: 38–42, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbert J Neuroendocrine responses to social stress. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 1: 467–490, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinman F, Baumann FW. Vesical and ureteral damage from voiding dysfunction in boys without neurologic or obstructive disease. J Urol 109: 727–732, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoshaw BA, Evans JC, Mueller B, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Social competition in rats: cell proliferation and behavior. Behav Brain Res 175: 343–351, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaferi A, Bhatnagar S. Corticosterone can act at the posterior paraventricular thalamus to inhibit hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in animals that habituate to repeated stress. Endocrinology 147: 4917–4930, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keay KA, Bandler R. Parallel circuits mediating distinct emotional coping reactions to different types of stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25: 669–678, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiddoo DA, Valentino RJ, Zderic S, Ganesh A, Leiser SC, Hale L, Grigoriadis DE. Impact of the state of arousal and stress neuropeptides on urodynamic function in the freely moving rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1697–R1706, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klausner AP, Streng T, Na YG, Raju J, Batts TW, Tuttle JB, Andersson KE, Steers WD. The role of corticotropin releasing factor and its antagonist, astressin, on micturition in the rat. Auton Neurosci 123: 26–35, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koolhaas JM, De Boer SF, De Rutter AJ, Meerlo P, Sgoifo A. Social stress in rats and mice. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 640: 69–72, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korosi A, Kozicz T, Richter J, Veening JG, Olivier B, Roubos EW. Corticotropin-releasing factor, urocortin 1, and their receptors in the mouse spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 502: 973–989, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaBerge J, Malley SE, Zvarova K, Vizzard MA. Expression of corticotropin-releasing factor and CRF receptors in micturition pathways after cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R692–R703, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lettgen B, von Gontard A, Olbing H, Heiken-Lowenau C, Gaebel E, Schmitz I. Urge incontinence and voiding postponement in children: somatic and psychosocial factors. Acta Paediatr 91: 978–984, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loewy AD, Saper CB, Baker RP. Descending projections from the pontine micturition center. Brain Res 172: 533–538, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lumley LA, Sipos ML, Charles RC, Charles RF, Meyerhoff JL. Social stress effects on territorial marking and ultrasonic vocalizations in mice. Physiol Behav 67: 769–775, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malmgren A, Sjogren C, Uvelius B, Mattiasson A, Andersson KE, Andersson PO. Cystometrical evaluation of bladder instability in rats with infravesical outflow obstruction. J Urol 137: 1291–1294, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto G, Hisamitsu T, de Groat WC. Non-NMDA glutamatergic excitatory transmission in the descending limb of the spinobulbospinal micturition reflex pathway of the rat. Brain Res 693: 246–250, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto G, Hisamitsu T, de Groat WC. Role of glutamate and NMDA receptors in the descending limb of the spinobulbospinal micturition reflex pathway of the rat. Neurosci Lett 183: 58–61, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McEwen Stress BS, adaptation, disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci 840: 33–44, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miczek KA A new test for aggression in rats without aversive stimulation: differential effects of d-amphetamine and cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 60: 253–259, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavcovich LA, Valentino RJ. Central regulation of micturition in the rat by corticotropin- releasing hormone from Barrington's nucleus. Neurosci Lett 196: 185–188, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Persson K, Pandita RK, Spitsbergen JM, Steers WD, Tuttle JB, Andersson KE. Spinal and peripheral mechanisms contributing to hyperactive voiding in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R1366–R1373, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romans S, Belaise C, Martin J, Morris E, Raffi A. Childhood abuse and later medical disorders in women. An epidemiological study. Psychother Psychosom 71: 141–150, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rovner ES, Wein AJ. Incidence and prevalence of overactive bladder. Curr Urol Rep 3: 434–438, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rygula R, Abumaria N, Flugge G, Fuchs E, Ruther E, Havemann-Reinecke U. Anhedonia and motivational deficits in rats: impact of chronic social stress. Behav Brain Res 162: 127–134, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakanaka M, Shibasaki T, Lederis K. Distribution and efferent projections of corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in the rat amygdaloid complex. Brain Res 382: 213–238, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Vale WW. Co-expression of corticotropin-releasing factor and vasopressin immunoreactivity in parvocellular neurosecretry neurons of the adrenalectomized rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 1883–1887, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steers WD Rat: overview and innervation. Neurourol Urodyn 13: 97–118, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steers WD, Tuttle JB. Mechanisms of Disease: the role of nerve growth factor in the pathophysiology of bladder disorders. Nat Clin Pract Urol 3: 101–110, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. Behavioral and autonomic responses to intermittent social stress: differential protection by clonidine and metoprolol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 116: 346–356, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science 213: 1394–1397, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valentino RJ, Page ME, Luppi PH, Zhu Y, Van Bockstaele E, Aston-Jones G. Evidence for widespread afferents to Barrington's nucleus, a brainstem region rich in corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Neuroscience 62: 125–143, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valentino RJ, Page ME, Van Bockstaele E, Aston-Jones G. Corticotropin-releasing factor innervation of the locus coeruleus region: distribution of fibers and sources of input. Neuroscience 48: 689–705, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EEO, Valentino RJ. Amygdaloid corticotropin-releasing factor targets locus coeruleus dendrites: substrate for the coordination of emotional and cognitive limbs of the stress response. J Neuroendocrinol 10: 743–757, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EEO, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor- containing axon terminals synapse onto catecholamine dendrites and may presynaptically modulate other afferents in the rostral pole of the nucleus locus coeruleus in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 364: 523–534, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viau V, Chu A, Soriano L, Dallman MF. Independent and overlapping effects of corticosterone and testosterone on corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and stress-induced adrenocorticotropic hormone release. J Neurosci 19: 6684–6693, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vincent SR, Satoh K. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) immunoreactivity in the dorsolateral pontine tegmentum: further studies on the micturition reflex system. Brain Res 308: 387–391, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vizzard MA Neurochemical plasticity and the role of neurotrophic factors in bladder reflex pathways after spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res 152: 97–115, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshiyama M, Roppolo JR, de Groat WC. Effects of MK-801 on the micturition reflex in the rat-possible sites of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265: 844–850, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zderic SA, Butler S, Chang AY, Siliwoski J, Canning DA, Valentino RJ. Sociobiology-social stress induced voiding dysfunction leads to murine bladder wall hypertrophy. Am Acad Ped Section on Urology Abstr. http://www.aap.org/sections/urology/default.cfm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.