Abstract

Background and objectives: Data regarding renal biopsy in the very elderly (≥age 80 yr) are extremely limited. The aim of this study was to examine the causes of renal disease and their clinical presentations in very elderly patients who underwent native renal biopsy.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: All native renal biopsies (n = 235 including 106 men, 129 women) performed in patients aged ≥80 yr over a 3.67-yr period were retrospectively identified. Results were compared with a control group of 264 patients aged 60 to 61 who were biopsied over the same period.

Results: The indications for biopsy were acute kidney injury (AKI) in 46.4%, chronic-progressive kidney injury in 23.8%, nephrotic syndrome (NS) in 13.2%, NS with AKI in 9.4%, and isolated proteinuria in 5.5%. Pauci-immune GN was the most frequent diagnosis (19%), followed by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis secondary to hypertension (7.6%), hypertensive nephrosclerosis (7.1%), IgA nephropathy (7.1%) and membranous nephropathy (7.1%). Comparison with the control group showed pauci-immune GN to be more frequent (P < 0.001) and diabetic glomerulosclerosis (P < 0.001) and membranous nephropathy (P < 0.05) less frequent in the very elderly. Diagnostic information had the potential to modify treatment in 67% of biopsies from the very elderly, particularly in those with AKI or NS.

Conclusions: Renal biopsy in very elderly patients is a valuable diagnostic tool that should be offered in clinical settings with maximal potential benefit. Advanced age per se should no longer be considered a contraindication to renal biopsy.

The elderly population in the United States is growing. In 2003, people aged 65 and older comprised 12% of the total population. This number is projected to increase from 26 million in 2003 to 72 million in 2030, at which point the elderly will comprise 20% of the population (1). In addition, patients aged 85 or more represented 1.6% of the total population in 2003, but they are projected to double from 4.7 million in 2003 to 9.6 million by 2030 and to double again to 20.9 million by 2050. Moreover, between 1980 and 1997 there was an 18% increase in individuals more than 65 yr of age and a 73% increase in those older than 85 yr (2). As life expectancy increases, more elderly patients are surviving longer with acute and chronic diseases. In particular, renal disease is increasingly common in the elderly. A progressive decline in GFR with age or in the course of cardiovascular or other systemic diseases, as well as because of the potential nephrotoxic effects of medical and surgical treatments, may contribute to the increased incidence of renal disease in this population. Advanced age is no longer considered a contraindication for renal biopsy, immunosuppressive therapy, or renal replacement therapy, and consequently the number of diagnostic renal biopsies performed in the very elderly is increasing. Recent studies in limited numbers of very elderly patients suggest that renal biopsy can provide significant diagnostic and prognostic information, leading to change of treatment in as many as 40% of patients (3,4).

Several studies have focused on the findings in renal biopsies in elderly patients (4–13). However, most of these studies considered elderly patients in the age groups of over 60 or 65 yr. Only two of these studies included a subset analysis for patients aged over 80 yr, and then in limited numbers (4,14). In addition, some of these studies contained relatively few patients (11,12) and the clinical presentations and indications for biopsy were not always clearly defined. In the last 2 decades, only one study (3) has focused on renal biopsy findings in very elderly patients (>80 yr), reporting on only 100 patients without clear delineation of the indications for biopsy.

The aim of this study was to examine the specific causes of renal disease and their respective clinical presentations in a large group of elderly patients aged ≥80 yr who underwent native renal biopsy and to compare the frequency of these diagnoses with a control group of patients aged 60 to 61 yr. In addition, we retrospectively sought to determine the utility of renal biopsy in the very elderly by categorizing biopsy results into those which potentially affect patient management versus those revealing chronic, age-related conditions or conditions managed by nonspecific or supportive therapies.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study identified all patients aged ≥80 yr whose native renal biopsy specimens were processed at the Renal Pathology Laboratory at Columbia University Medical Center during a 3.67-yr period from January 2005 to August 2008. During this time, a total of 7690 native renal biopsies were analyzed by the laboratory, of which 235 (3.1%) were from patients ≥80 yr. Each specimen was examined with light microscopy, direct immunofluorescence (for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C1q, fibrinogen, kappa and lambda lights chains), and electron microscopy when sufficient tissue was available. Only three biopsies were inadequate for diagnosis. One of these was subsequently repeated, and only the results of the second adequate biopsy are included for analysis.

For each case, the biopsy report was reviewed along with the clinical information provided by the referring nephrologist. Clinical information included medical history, physical examination, and laboratory data. The biopsy report was reviewed by a pathologist to determine the major diagnosis or diagnoses. From the clinical information provided, an indication for biopsy was determined according to the following clinical categories:

Acute Kidney Injury: Clinical presentation was defined as acute kidney injury (AKI) if the indication recorded by the nephrologist was AKI, acute renal failure, acute on chronic renal failure, rapidly progressive GN, or if the clinical picture illustrated by the patients’ clinical data made a deterioration of renal function unlikely to be due to chronic kidney injury (i.e., absence of anemia, absence of small kidneys on renal ultrasound, or improvement of renal function over time). If no definite indication was provided by the referring physician, AKI was presumed (1) if serum creatinine doubled in patients with prior normal renal function, (2) if serum creatinine increased by 50% over <1 yr in patients with chronic kidney injury, and (3) if serum creatinine was >2 mg/dl in patients with unknown baseline renal function. Patients in the AKI category could also present with or without proteinuria and/or hematuria. Patient with AKI and nephrotic syndrome (NS) as defined below were classified separately as “AKI and NS”.

Chronic-Progressive Kidney Injury: Patients were included in this group when the decline in renal function was less severe and/or less abrupt than defined for AKI. Chronic-progressive kidney injury could occur with or without proteinuria and/or hematuria, as defined below. Patients with NS and chronic-progressive kidney injury were categorized under NS.

NS: NS was defined as proteinuria >3.5 g/d with edema and/or hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin <3.5 g/dl), without AKI, with or without hematuria. If there was no information regarding the presence of edema, patients were included in this group if the presentation was described as NS by their referring nephrologist.

Proteinuria (without NS): Proteinuria without NS was defined as <3.5 g/d or proteinuria >3.5 g/d not accompanied by edema or hypoalbuminemia. All patients in this group were without significant decline in renal function as stated above and without hematuria.

Proteinuria and Hematuria: Proteinuria and hematuria was defined as proteinuria as defined above plus the presence of hematuria (>5 erythrocytes per high-power field on microscopic examination of the urine or a positive heme reaction on dipstick), without significant decline in renal function.

Hematuria: Hematuria was defined as the presence of hematuria as defined above without proteinuria or significant decline in renal function.

For each biopsy, pathologic diagnoses and epidemiologic and clinical data were collected. Recorded data included age, gender, history of diabetes mellitus (and presence of retinopathy), systemic hypertension, chronic kidney injury, coronary artery disease, smoking, medications, and recent surgery or exposure to nephrotoxic agents. The following physical findings at presentation were recorded: presence of edema, rash, hypertension (defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg), pulmonary hemorrhage or infiltrates, and requirement for dialysis. Laboratory values routinely provided included urinalysis, serum creatinine, serum albumin, 24-h urine protein or urine protein/creatinine ratio, the results of all serologies performed, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, hematocrit, and renal ultrasound data.

To determine whether the incidence of various renal biopsy diagnoses in the very elderly was unique to this age group, the biopsy diagnoses were compared with those of a control group of 264 patients aged 60 to 61 yr biopsied over the same period.

For each biopsy diagnosis, the potential effect on medical management was assessed to determine whether the biopsy diagnosis was likely to alter therapy. For example, diseases like pauci-immune GN and acute interstitial nephritis were considered potentially amenable to targeted interventions in contrast to diseases such as acute tubular necrosis or hypertensive nephrosclerosis, in which supportive management is usually indicated. Biopsy diagnoses that were considered to potentially modify treatment included thrombotic microangiopathy, vasculitides, minimal change disease, primary or secondary glomerulonephritides, acute or granulomatous interstitial nephritis, dysproteinemia-related renal diseases (including amyloidosis, myeloma cast nephropathy, light chain deposition disease, light chain Fanconi syndrome, and renal infiltration by lymphoma), urate nephropathy, oxalate nephropathy, and pyelonephritis. Biopsy results that were considered unlikely to lead to specific modifications of therapy included diabetic glomerulosclerosis; acute tubular necrosis; atheroembolic disease; hypertensive nephrosclerosis; focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) secondary to hypertension/aging; nodular glomerulosclerosis secondary to hypertension/smoking or idiopathic; chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy; end stage kidney; and inadequate biopsies.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were reported as median (range), unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed using SPPS for Mac, version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Comparisons regarding categorical variables among the groups of different indications or diagnoses were performed using the Pearson χ2 or Fischer exact test, where appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using Mann–Whitney U test. A P value <0.05 (by two-tailed testing) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Results

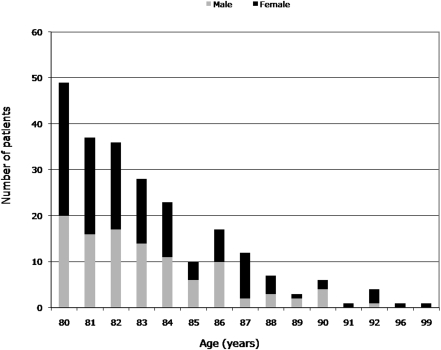

Of 7690 native renal biopsies specimens processed by the Renal Pathology Laboratory of Columbia University from 2005 to 2008, 3.1% were performed in patients ≥80 yr old. These 235 patients included 106 men and 129 women with a median age of 82 (range 80 to 99). Figure 1 shows the number of patients distributed by age and by gender. Data on race were available in 141 patients (60% of the total): 124 patients were Caucasians (53 men and 71 women) representing 87.9% of the patients with available data.

Figure 1.

Distribution of very elderly patients who underwent renal biopsy by age and gender.

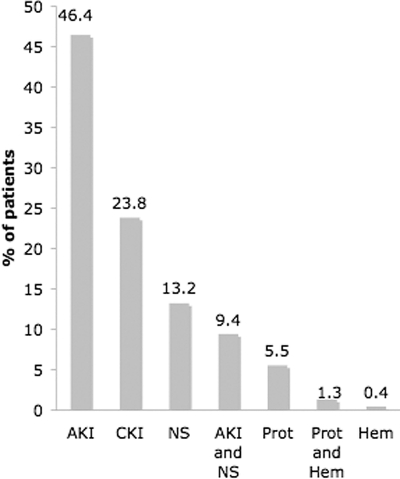

Indications for biopsy are shown in Figure 2. The most frequent indication for renal biopsy in the very elderly was AKI, accounting for almost half of the patients (46%). Chronic-progressive kidney injury (24%) and NS (13%) were the other most common indications. Interestingly, an additional 22 (9.4%) patients presented with AKI and NS. Women were more likely to present with AKI (without NS) than men (70 versus 39, P = 0.008).

Figure 2.

Indications for renal biopsy. AKI, acute kidney injury; CKI, chronic-progressive kidney injury; NS, nephrotic syndrome; Prot, proteinuria; Hem, hematuria.

Specific renal biopsy diagnoses by clinical presentation in the very elderly are shown in Table 1. Almost one-third of patients (33%) presenting with AKI were found to have pauci-immune GN. Myeloma cast nephropathy was the second most common finding within the AKI group but at a much lower incidence (8%). When NS accompanied AKI, the most common diagnosis was minimal change disease (MCD), which was seen in one-quarter of these patients. In contrast, approximately half of the patients who underwent renal biopsy because of a slowly progressive decline in renal function exhibited findings of nephrosclerosis related to hypertension and/or aging. The single patient presenting with hematuria, who had an inadequate biopsy, has not been included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Renal biopsy diagnoses by clinical presentation in the very elderlya

| Acute Kidney Injury | n(%) | Chronic-Progressive Kidney Injury | n(%) | Nephrotic Syndrome | n(%) | Acute Kidney Injury and Nephrotic Syndrome | n (%) | Proteinuria | n (%) | Proteinuria and Hematuria | n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauci-immune GN | 32 (33) | FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 12 (24) | Membranous nephropathy | 10 (34.5) | MCD | 5 (25) | HTN nephrosclerosis | 3 (25) | Membranous nephropathy | 1 (50) |

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | 8 (8.2) | HTN nephrosclerosis | 10 (20) | Amyloidosis | 8 (27.6) | Pauci-immune GN | 2 (10) | FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 3 (25) | Amyloidosis | 1 (50) |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | 7 (7.2) | Pauci-immune GN | 5 (10) | MCD | 3 (10.3) | Primary FSGS | 1 (5) | NSG-smoking related | 2 (16.6) | ||

| IgA nephropathy | 7 (7.2) | IgA nephropathy | 4 (8) | IgA nephropathy | 2 (6.9) | Membranous nephropathy | 1 (5) | Membranous nephropathy | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Acute tubular necrosis | 5 (5.2) | CTIN | 4 (8) | Primary FSGS | 1 (3.4) | IgA nephropathy | 1 (5) | IgA nephropathy | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Atheroembolic disease | 4 (4.1) | Membranous nephropathy | 2 (4) | Diabetic GS | 1 (3.4) | Diabetic GS | 1 (5) | Amyloidosis | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Granulomatous INb | 4 (4.1) | Diabetic GS | 2 (4) | Lupus nephritis | 1 (3.4) | Myeloma cast nephropathy | 1 (5) | MCD | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Diabetic GS | 3 (3.1) | NSG-smoking related | 2 (4) | Idiopathic MPGN | 1 (3.4) | Amyloidosis | 1 (5) | Total | 12 (100) | Total | 2 (100) |

| CTIN | 3 (3.1) | TMA | 2 (4) | NSG-smoking related | 1 (3.4) | MPGN secondary to HCV-associated cryoglobulinemia | 1 (5) | ||||

| Acute postinfectious GN | 3 (3.1) | MPGN (1 idiopathic and 1 HCV-associated) | 2 (4) | Immunotactoid GN | 1 (3.4) | Acute postinfectious GN | 1 (5) | ||||

| Anti-GBM nephritis | 3 (3.1) | Primary FSGS | 1 (2) | Light chain deposition disease | 1 (5) | ||||||

| Primary FSGS | 2 (2.1) | LCFS | 1 (2) | FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 1 (5) | ||||||

| Amyloidosis | 2 (2.1) | FSGS secondary to HTN/smoking | 1 (2) | FSGS secondary to HTN/smoking | 1 (5) | ||||||

| HTN nephrosclerosis | 2 (2.1) | Urate nephropathy | 1 (2) | Proliferative GN with monoclonal IgG3 λ | 1 (5) | ||||||

| Oxalate nephropathy | 2 (2.1) | End stage kidney | 1 (2) | Cortical necrosis secondary to thromboembolism | 1 (5) | ||||||

| Exudative GN NOS | 2 (2.1) | ||||||||||

| Lupus nephritis | 1 (1) | Total | 50(100) | Total | 29 (100) | Total | 20 (100) | ||||

| MPGN secondary to essential cryoglobulinemia | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| LCFS | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Anti-TBM nephritis | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| NSG-smoking related | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Pyelonephritis | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Arteritis | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Inadequate | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Total | 97 (100) |

Patients with multiple diagnoses are presented separately.

GS, glomerulosclerosis; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; NOS, not otherwise specified; MPGN, membranoproliferative GN; LCFS, light-chain Fanconi syndrome; TBM, tubular basement membrane; NSG, nodular sclerosing glomerulopathy; HTN, hypertension; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; MCD, minimal change disease; CTIN, chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; IN, interstitial nephritis.

Twenty-four renal biopsies had two concurrent major diagnoses (n = 24), as shown in Table 2. In these patients, both conditions were considered to be significant contributors to the clinical presentation. Most of these were patients with underlying diabetic glomerulosclerosis or hypertensive nephrosclerosis who developed an acute process superimposed on their chronic condition.

Table 2.

Renal biopsies with two major diagnoses in the very elderly

| Clinical Presentation | First Diagnosis | Second Diagnosis | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute kidney injury (AKI) | Diabetic GS | CTIN | 1 |

| Diabetic GS | Acute tubular necrosis | 1 | |

| Diabetic GS | Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 1 | |

| Diabetic GS | IgA nephropathy | 1 | |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | Acute interstitial nephritis | 1 | |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | Atheroembolic disease | 2 | |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | Acute tubular necrosis | 2 | |

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | Light chain deposition disease | 1 | |

| Secondary FSGS due to solitary functioning kidney | Acute tubular necrosis | 1 | |

| IgA nephropathy | Atheroembolic disease | 1 | |

| Chronic-progressive kidney injury | Diabetic GS | TMA associated with malignant HTN | 1 |

| Diabetic GS | FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 1 | |

| Diabetic GS | Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 1 | |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | Acute tubular necrosis | 1 | |

| NSG-smoking related | Atypical lymphocytic infiltrate/chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 1 | |

| CTIN | Pauci-immune GN | 1 | |

| Nephrotic syndrome | Diabetic GS | Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 1 |

| FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | TMA associated with malignant HTN | 1 | |

| AKI and nephrotic syndrome | Diabetic GS | Acute postinfectious GN | 1 |

| MCD | TMA of unknown etiology | 1 | |

| Proteinuria | FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | MCD | 1 |

| Proteinuria and hematuria | Diabetic GS | Pauci-immune GN | 1 |

| Total | 24 |

FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HTN, hypertension; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; CTIN, chronic tubulo-interstitial nephropathy; MCD, minimal change disease; NSG, nodular sclerosing glomerulopathy.

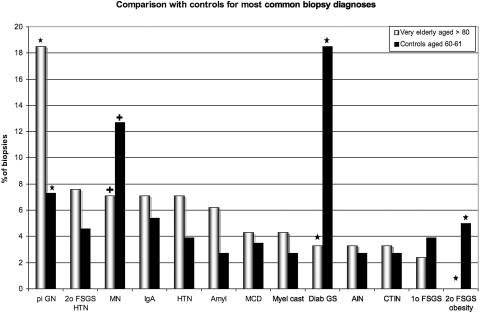

The most common renal biopsy findings in the very elderly patients are shown in Figure 3, excluding the 24 patients with two concurrent diagnoses. Pauci-immune GN was most frequent, seen in almost 19% of biopsies. Hypertensive nephrosclerosis and FSGS secondary to hypertension and aging were noted in 7.1 and 7.6% of patients, respectively. IgA nephropathy and membranous nephropathy were equally common and identified in 7.1% of all biopsies. Amyloidosis, MCD, and myeloma cast nephropathy were each seen in approximately 5% of patients.

Figure 3.

Most common biopsy diagnoses. Biopsies with double diagnoses are excluded. pi GN, pauci-immune GN; 2o FSGS HTN, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) secondary to hypertension/aging; HTN, hypertensive nephrosclerosis; IgA, IgA nephropathy; MN, membranous nephropathy; Amyl, amyloidosis; MCD, minimal change disease; Myel Cast, myeloma cast nephropathy.

In patients biopsied for NS alone, membranous nephropathy (34.5%) and amyloidosis (27.6%) were most common, followed by MCD (10.3%) and IgA nephropathy (6.9%). These four diagnoses made up almost 80% of all biopsies presenting with the NS. Table 3 shows the most frequent diagnoses in patients who presented with NS, with and without coexistent AKI. Collectively, membranous nephropathy, amyloidosis, and MCD accounted for 56% of these patients. Of note, the 13 patients with amyloidosis included 12 patients with primary (AL) amyloidosis and one with secondary (AA) amyloidosis.

Table 3.

Most common etiologies of nephrotic syndrome in the very elderlya

| Biopsy Diagnosis | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Membranous nephropathy | 11 | 22 |

| Amyloidosis | 9 | 18 |

| MCD | 8 | 16 |

| IgA nephropathy | 3 | 6 |

| Pauci-immune GN | 2 | 4 |

| MPGN | 2 | 4 |

| Diabetic GS | 2 | 4 |

| FSGS (primary) | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 39 | 78 |

Biopsies with multiple diagnoses are excluded. MCD, minimal change disease; GN, glomerulonephritis; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; GS, glomerulosclerosis; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

Table 4 shows the clinical presentations of the patients whose biopsies received the most common diagnoses and Table 5 shows their clinical characteristics. Patients with pauci-immune GN and myeloma cast nephropathy presented almost exclusively with AKI, whereas patients with underlying hypertensive lesions had chronic-progressive kidney injury. Approximately half of the patients with IgA nephropathy underwent renal biopsy because of AKI, whereas chronic-progressive kidney injury was the second most common indication. Patients with membranous nephropathy and amyloidosis most frequently developed NS, whereas patients diagnosed with MCD presented with NS with or without AKI.

Table 4.

Clinical presentations of the most common biopsy diagnosesa

| Clinical Presentation | AKIan (%) | CKI n (%) | NS n (%) | AKI + NS n (%) | Prot n (%) | Prot and Hem n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauci-immune GN | 32(82) | 5(12.8) | 2(5.1) | 39(100) | |||

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 2(13.3) | 10(66.7) | 3(20) | 15(100) | |||

| FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 12(75) | 1(6.2) | 3(18.8) | 16(100) | |||

| IgA nephropathy | 7(46.7) | 4(26.7) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 1(6.7) | 15(100) | |

| Membranous nephropathy | 2(13.3) | 10(66.7) | 1(6.7) | 1(6.7) | 1(6.7) | 15(100) | |

| Amyloidosis | 2(15.4) | 8(61.5) | 1(7.7) | 1(7.7) | 1(7.7) | 13(100) | |

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | 8(88.9) | 1(11.1) | 9(100) | ||||

| MCD | 3(33.3) | 5(55.6) | 1(11.1) | 9(100) |

Biopsies with multiple diagnoses are excluded.

bAKI, acute kidney injury; CKI, chronic-progressive kidney injury; NS, nephrotic syndrome; Prot, proteinuria; Hem, hematuria; GN, glomerulonephritis; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; MCD, minimal change disease; HTN, hypertension.

Table 5.

| Biopsy Diagnosis | n | Male | HTNc | Hematuria | Nephrotic Range | Serum Albumin (g/dl) | Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | Urine Protein(g/24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauci-immune GN | 39 | 26%(10/39) | 50%(9/18) | 97%(32/33) | 24%(5/21) | 2.6±0.6(22/39) | 4.4±2.9(36/39) | 2.948±3.104(20/39) |

| FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 16 | 56%(9/16) | 67%(4/6) | 30%(3/10) | 33%(5/15) | 3.3±0.6(9/16) | 2.7±1.1(16/16) | 3.368±1.984(15/16) |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 15 | 53%(8/15) | 50%(4/8) | 0%(0/8) | 17%(2/12) | 3.9±0.5(9/15) | 2.3±0.73(15/15) | 1.673±2.044(12/15) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 15 | 33%(5/15) | 57%(4/7) | 54%(7/13) | 85%(11/13) | 2.2±0.5(14/15) | 1.5±0.8(14/15) | 8.207±4.389(13/15) |

| IgA nephropathy | 15 | 87%(13/15) | 33%(2/6) | 80%(12/15) | 31%(4/13) | 3±0.5(11/15) | 3.2±1.3(13/15) | 3.477±3.104(11/15) |

| Amyloidosis | 13 | 69%(9/13) | 0%(0/6) | 30%(3/10) | 75%(9/12) | 2.3±1.1(12/13) | 2.3±2.9(12/13) | 7.010±5.308(10/13) |

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | 9 | 33%(3/9) | 0%(0/2) | 40%(2/5) | 60%(3/5) | 3.5±1.1(7/9) | 5.2±2.7(8/9) | 3.580±1.362(5/9) |

| MCD | 9 | 67%(6/9) | 40%(2/5) | 38%(3/8) | 89%(8/9) | 2.3±0.4(8/9) | 2.4±1.6(7/9) | 8.651±5.391(9/9) |

Biopsies with multiple diagnoses are excluded.

Serum albumin, serum creatinine level, and 24-h urine protein level are expressed as the mean ± SD, whereas the fraction in parentheses represents the number of patients for whom data was available. For categorical variables, the numerator represents the number of patients with a particular finding and the denominator represents the total number of patients with available data. Hematuria includes gross and/or microscopic hematuria.

HTN, presence of HTN at presentation; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HTN, hypertension; MCD, minimal change disease.

Pauci-immune GN was the most frequent biopsy diagnosis presenting mainly as AKI. A positive perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA; by indirect immunofluorescence) or myeloperoxidase-ANCA (by ELISA) was found in 63% of patients with pauci-immune GN, whereas cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) or proteinase-3 ANCA (PR3-ANCA) was only positive in 12% (Table 6). No patient had an additional diagnosis of anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis. Twelve patients (29.3%) presented with pulmonary-renal syndrome. Almost 75% of patients with pauci-immune GN were women (30 women versus 11 men, P = 0.01).

Table 6.

| ANCA | n (%) | Pulmonary Infiltrates |

|---|---|---|

| Pauci-immune GN | 41(100) | 12 |

| p-ANCA (MPO) | 26(63) | 8 |

| c-ANCA (PR-3) | 5(12) | 2 |

| Both ANCA positive | 0 | 0 |

| Both ANCA negative | 1(2.4) | 1 |

| Both ANCA unknown | 9(22) | 1 |

Biopsies with multiple diagnoses are included.

p-ANCA, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; c-ANCA, cytoplasmic ANCA; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PR-3, proteinase-3.

The biopsy reports of 264 patients (162 men and 102 women) aged 60 to 61 yr biopsied over the same period were used to create the control group. The frequencies of the most common diagnoses are shown in comparison to those of the very elderly patients in Table 7 and Figure 4. As in the very elderly age group, patients with two diagnoses (n = 5) were excluded from analysis. Among the controls, the diagnosis of pauci-immune GN was less frequent and the diagnosis of diabetic glomerulosclerosis was much more frequent with high significance (P < 0.001). Membranous nephropathy was also more common in the 60- to 61-yr-old age group (P < 0.05). FSGS secondary to obesity was seen only in the control group.

Table 7.

Most common renal biopsy diagnoses comparing very elderly and control patientsa

| Diagnosis | Very Elderly (%) | Control Group (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pauci-immune GN | 39(18.5) | 19(7.3) | <0.001 |

| FSGS secondary to HTN/aging | 16(7.6) | 12(4.6) | 0.179 |

| Membranous nephropathy | 15(7.1) | 33(12.7) | 0.045 |

| IgA nephropathy | 15(7.1) | 14(5.4) | 0.445 |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 15(7.1) | 10(3.9) | 0.119 |

| Amyloidosis | 13(6.2) | 7(2.7) | 0.065 |

| MCD | 9(4.3) | 9(3.5) | 0.657 |

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | 9(4.3) | 7(2.7) | 0.353 |

| Diabetic GS | 7(3.3) | 48(18.5) | <0.001 |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | 7(3.3) | 7(2.7) | 0.700 |

| CTIN | 7(3.3) | 7(2.7) | 0.700 |

| Primary FSGS | 5(2.4) | 10(3.9) | 0.360 |

| FSGS secondary to obesity | 0(0) | 13(5) | 0.001 |

| Totals | 211(100) | 259(100) |

Biopsies with multiple diagnoses are excluded. GN, glomerulonephritis; HTN, hypertension; CTIN, chronic tubulo-interstitial nephropathy; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; MCD, minimal change disease.

Figure 4.

Most common diagnoses, showing control comparison with 60- to 61-yr-old patients. Biopsies with double diagnoses are excluded. pi GN, pauci-immune GN; 2o FSGS HTN, FSGS secondary to hypertension/aging; MN, membranous nephropathy; HTN, hypertensive nephrosclerosis; Amyl, amyloidosis; MCD, minimal change disease; Myel Cast, myeloma cast nephropathy; Diab GS, diabetic glomerulosclerosis, AIN, acute interstitial nephritis; CTIN, chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy; 1o FSGS, primary FSGS; 2o FSGS obesity, FSGS secondary to obesity. * indicates highly significant comparison (P < 0.001), + indicates significant comparison (P < 0.05).

Eighteen patients in the very elderly group presented with significant decline in their renal function requiring dialysis at presentation. Of these, 15 presented with AKI (one of them had NS along with AKI), whereas the other 3 had chronic-progressive kidney injury. The most common renal biopsy findings in patients on dialysis at the time of biopsy were pauci-immune GN, myeloma cast nephropathy, acute tubular necrosis, and anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis; only two patients were diagnosed with diabetic glomerulosclerosis.

In approximately 70% of biopsies, a disease that is potentially amenable to treatment was identified (Table 8). Diagnoses that might alter therapy were more frequently made in patients with AKI or NS, whereas patients with chronic-progressive kidney injury and those with proteinuria not fulfilling the criteria for NS were less likely to have a condition for which treatment would be guided by biopsy results. Additionally, findings that could potentially change treatment were more frequent in patients with hematuria, a positive ANCA, or in the absence of a history of chronic kidney injury.

Table 8.

Biopsy results that potentially do or do not modify treatmenta

| Variable | Modifies Treatment, n (%) | Does Not Modify Treatment, n (%) | Total n | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| AKI | 82(52) | 27(35) | 109 | 0.01 |

| CKI | 21(13) | 35(45) | 56 | <0.001 |

| NS | 28(18) | 3(4) | 31 | 0.003 |

| AKI and NS | 18(12) | 4(5) | 22 | 0.116 |

| proteinuria | 5(3) | 8(10) | 13 | 0.03 |

| proteinuria and hematuria | 3(2) | 0(0) | 3 | – |

| hematuria | 0(0) | 1(1) | 1 | – |

| total | 157(67) | 78(33) | 235 | |

| History of chronic kidney injury | 43(41) | 32(68) | 75 | 0.002 |

| Microhematuria | 84(70) | 19(40) | 103 | <0.001 |

| Positive ANCA | 40(49) | 5(16) | 45 | <0.001 |

Biopsies with multiple diagnoses are included. See text for listing of renal biopsy diagnoses predicted to modify specific therapy on which this analysis was based. AKI, acute kidney injury; CKI, chronic-progressive kidney injury; NS, nephrotic syndrome; ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this retrospective study constitutes the largest renal biopsy series of patients aged ≥80 yr. Most previously published studies and renal registries have combined all patients 65 yr and older into a single group. Although in some of those reports, AKI and acute nephritic syndrome are recorded separately, we included both entities under AKI. In very elderly patients, this approach may be more practical because the presence of age-related comorbidities may hamper determination of the time and the specificity of presenting symptoms.

In our series, there was a slight predominance of women. This was also reported in the previous study of very elderly patients by Nair et al. (3); Haas et al. reported an almost equal number of male and female patients over 80 yr old who underwent renal biopsy because of AKI (4). However, in previously reported renal pathology registries with a broad definition of elderly (patients >65 yr), men had significantly outnumbered women among patients who received renal biopsy (14,15), which is indeed supported by the male predominance in our control group of patients aged 60 to 61 yr. In our very elderly group (patients ≥80 yr), women represented the majority, likely due largely to their greater life expectancy.

AKI was the most common indication for renal biopsy in our study. In a previous study of the same age group (3), AKI was the second most frequent clinical presentation after NS; however, in that study, acute nephritic syndrome and rapidly progressive renal failure were classified separately. If these groups were classified as AKI (as in our study), AKI would then have been the most frequent indication for biopsy. Other studies regarding renal biopsies in the elderly included patients over 60 or 65 yr old; in most of the studies (4,5,14,16–19), nephrotic proteinuria was the most common indication for renal biopsy, followed by AKI (including acute nephritic syndrome). In a recent report from the Spanish Registry of GN (20), AKI was the most frequent indication for renal biopsy in the elderly if AKI and acute nephritic syndrome were included in the same group. Nevertheless, it has been stated that renal biopsy in elderly patients presenting with AKI may not be required in most patients (21). In a recent study, patients with acute tubular necrosis, prerenal and obstructive AKI were diagnosed on clinical grounds alone in 76% of patients (22). However, despite improvement in agreement between clinical and biopsy diagnoses, in one-third of patients over age 60 yr the biopsy diagnosis was different from the clinical impression (4). In our study, only 5% of patients with AKI were diagnosed with acute tubular necrosis, indicating excellent clinical triage for biopsy by the referring nephrologists.

Membranous nephropathy, amyloidosis, and MCD were the most frequent diagnoses in our very elderly patients who presented with NS. Our results are consistent with most studies in patients over 65 yr (6,9,14,19,23–26), which showed that membranous nephropathy was the most common diagnosis, followed by amyloidosis and MCD. However, there are reports recording relatively high frequencies of FSGS in nephrotic patients over 65 yr old (8,17,24). It is possible that a considerable number of these represent unrecognized secondary forms related to hypertension, obesity, or other processes. Only five patients (2%) in our study were diagnosed with primary FSGS because we carefully sought to exclude secondary forms. In fact, more of our patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis had a pattern of secondary FSGS than not, and among these, one-third presented with nephrotic-range proteinuria (mean urine protein 3.368 g for this group). It is likely that the presence of heavy proteinuria in the chronic hypertensive patient was considered by the clinician to be sufficiently atypical to warrant biopsy.

The lower incidence in the very elderly patients versus controls of both diabetic nephrosclerosis (3 versus 19%) and of FSGS secondary to obesity (0 versus 5%) demonstrates the different clinical contexts and diagnostic questions in the very elderly group. Obesity is an independent risk factor for secondary FSGS (27) that is not represented at all in our biopsy population of very elderly patients, possibly due in part to its lower life expectancy.

Interestingly, pauci-immune GN was the most frequent biopsy finding in our study, accounting for almost 19% of all diagnoses, as opposed to 7% among the 60- to 61-yr-old controls. The high frequency of this crescentic GN was also reported in multiple additional studies on the elderly (3,9,14,18,20), and by Haas et al. (4), who found that pauci-immune GN was the cause of AKI in 27% of patients over 80 yr old. Our series also found pauci-immune GN in 10% of patients presenting with chronic-progressive renal failure, similar to a previous study by Ferro et al. (5). In our study, 29.3% of patients with pauci-immune GN had evidence of pulmonary involvement; this frequency was almost identical to that reported by Haas et al. (4) for patients over 80 yr old (29%). In conclusion, pauci-immune GN is very frequent in this age group. These findings highlight the importance of renal biopsy in settings where outcome is crucially dependent on rapid diagnosis and prompt initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

In an effort to examine the utility of renal biopsy in the very elderly population, Nair et al. (3) reported that in 40% of patients who underwent renal biopsy, the diagnosed renal condition was potentially amenable to targeted intervention. In our study, 67% (157 of 235) of patients had biopsy findings that could potentially lead to a change in treatment (Table 8). Not surprisingly, diseases that could modify treatment were more likely to present with AKI or NS. Therefore, clinical presentation may have a critical role in the decision to perform renal biopsy in this age group. Similarly, positive ANCA serologies, hematuria, and the absence of a history of chronic kidney injury also predicted a greater likelihood of a diagnosis that could potentially alter therapy. It should be carefully noted that many of these very elderly patients are likely to have had significant co-morbidities that would limit the ability to receive aggressive therapeutic intervention. Accordingly, not all patients with diagnoses that “could potentially alter therapy” were likely to have received disease-specific therapeutic interventions. Of note, even in patients where the biopsy diagnosis does not directly modify therapy, the biopsy offers prognostic information and can also eliminate potentially harmful empiric therapies. Future study of the clinical outcome in these patients is needed to determine whether they actually benefit from the management they receive. Bearing in mind that performing renal biopsies in very elderly patients is not associated with increased risk for complications (3,28), we believe that renal biopsy in this age group is a valuable diagnostic option that should be offered to patients given the appropriate indications and a clinical setting that maximizes the potential benefit.

In conclusion, renal biopsy in very elderly patients provides valuable information regarding diagnosis and prognosis in diverse clinical settings, particularly AKI or NS. Therefore, advanced age alone should no longer make physicians reluctant to perform renal biopsy. Given the trend toward greater longevity, it is time to reconsider the traditional definition of what constitutes elderly in the modern era and study more closely the renal diseases arising in the very elderly population.

Disclosures

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Wan H, Sengupta M, Velkoff V, DeBarros K: 65+ in the United States: 2005. In: Current Population Reports U.S. Census Bureau. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2005, pp 23–209

- 2.Abrass CK: Renal biopsy in the elderly. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 544–546, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair R, Bell JM, Walker PD: Renal biopsy in patients aged 80 years and older. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 618–626, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas M, Spargo BH, Wit EJ, Meehan SM: Etiologies and outcome of acute renal insufficiency in older adults: A renal biopsy study of 259 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 433–447, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferro G, Dattolo P, Nigrelli S, Michelassi S, Pizzarelli F: Clinical pathological correlates of renal biopsy in elderly patients. Clin Nephrol 65: 243–247, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vendemia F, Gesualdo L, Schena FP, D'Amico G: Epidemiology of primary glomerulonephritis in the elderly. Report from the Italian Registry of Renal Biopsy. J Nephrol 14: 340–352, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin JH, Pyo HJ, Kwon YJ, Chang MK, Kim HK, Won NH, Lee HS, Oh KH, Ahn C, Kim S, Lee JS: Renal biopsy in elderly patients: Clinicopathological correlation in 117 Korean patients. Clin Nephrol 56: 19–26, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preston RA, Stemmer CL, Materson BJ, Perez-Stable E, Pardo V: Renal biopsy in patients 65 years of age or older. An analysis of the results of 334 biopsies. J Am Geriatr Soc 38: 669–674, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modesto-Segonds A, Ah-Soune MF, Durand D, Suc JM: Renal biopsy in the elderly. Am J Nephrol 13: 27–34, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labeeuw M, Caillette A, Dijoud F: Renal biopsy in the elderly. Presse Med 25: 611–614, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran D, Korzets Z, Bernheim J, Bernheim J, Yaretzky A: Is renal biopsy justified for the diagnosis and management of the nephrotic syndrome in the elderly? Gerontology 39: 49–54, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moulin B, Dhib M, Sommervogel C, Dubois D, Godin M, Fillastre JP: Value of renal biopsy in the elderly. 32 cases. Presse Med 20: 1881–1885, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison AM, Johnston PA: Idiopathic glomerulonephritis in the elderly. Contrib Nephrol 105: 38–48, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera F, Lopez-Gomez JM, Perez-Garcia R: Clinicopathologic correlations of renal pathology in Spain. Kidney Int 66: 898–904, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schena FP: Survey of the Italian Registry of Renal Biopsies. Frequency of the renal diseases for 7 consecutive years. The Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 418–426, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covic A, Schiller A, Volovat C, Gluhovschi G, Gusbeth-Tatomir P, Petrica L, Caruntu ID, Bozdog G, Velciov S, Trandafirescu V, Bob F, Gluhovschi C: Epidemiology of renal disease in Romania: A 10-year review of two regional renal biopsy databases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 419–424, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rychlik I, Jancova E, Tesar V, Kolsky A, Lacha J, Stejskal J, Stejskalova A, Dusek J, Herout V: The Czech registry of renal biopsies. Occurrence of renal diseases in the years 1994–2000. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 3040–3049, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uezono S, Hara S, Sato Y, Komatsu H, Ikeda N, Shimao Y, Hayashi T, Asada Y, Fujimoto S, Eto T: Renal biopsy in elderly patients: A clinicopathological analysis. Ren Fail 28: 549–555, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison AM, Johnston PA: Glomerulonephritis in the elderly. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11[Suppl 9]: 34–37, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez-Gomez JM, Rivera F: Renal biopsy findings in acute renal failure in the cohort of patients in the Spanish Registry of Glomerulonephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 674–681, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macias-Nunez JF, Lopez-Novoa JM, Martinez-Maldonado M: Acute renal failure in the aged. Semin Nephrol 16: 330–338, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liano F, Pascual J: Epidemiology of acute renal failure: A prospective, multicenter, community-based study. Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int 50: 811–818, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron JS: Nephrotic syndrome in the elderly. Semin Nephrol 16: 319–329, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komatsuda A, Nakamoto Y, Imai H, Yasuda T, Yanagisawa MM, Wakui H, Ishino T, Satoh K, Miura AB: Kidney diseases among the elderly—A clinicopathological analysis of 247 elderly patients. Intern Med 32: 377–381, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison AM: Renal disease in the elderly. Contrib Nephrol 124: 126–137; discussion 137–145, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glassock RJ: Glomerular disease in the elderly population. Geriatr Nephrol Urol 8: 149–154, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ejerblad E, Fored CM, Lindblad P, Fryzek J, McLaughlin JK, Nyren O: Obesity and risk for chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1695–1702, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parrish AE: Complications of percutaneous renal biopsy: A review of 37 years’ experience. Clin Nephrol 38: 135–141, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]