Abstract

SNF1-related kinases (SnRK1s) play central roles in coordinating energy balance and nutrient metabolism in plants. SNF1 and AMPK, the SnRK1 homologs in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and mammals, are activated by phosphorylation of conserved threonine residues in their activation loops. Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) GRIK1 and GRIK2, which were first characterized as geminivirus Rep interacting kinases, are phylogenetically related to SNF1 and AMPK activating kinases. In this study, we used recombinant proteins produced in bacteria to show that both GRIKs specifically bind to the SnRK1 catalytic subunit and phosphorylate the equivalent threonine residue in its activation loop in vitro. GRIK-mediated phosphorylation increased SnRK1 kinase activity in autophosphorylation and peptide substrate assays. These data, together with earlier observations that GRIKs could complement yeast mutants lacking SNF1 activation activities, established that the GRIKs are SnRK1 activating kinases. Given that the GRIK proteins only accumulate in young tissues and geminivirus-infected mature leaves, the GRIK-SnRK1 cascade may function in a developmentally regulated fashion and coordinate the unique metabolic requirements of rapidly growing cells and geminivirus-infected cells that have been induced to reenter the cell cycle.

Protein kinases play central roles in signal transduction and regulatory pathways in eukaryotes. They often function as cascades in which upstream kinases activate downstream kinases by phosphorylating a Ser, Thr, or Tyr residue in the activation loop of the kinase domain. Phosphorylation induces a conformational change that moves the activation loop and allows access to the kinase active site. This mechanism is highly conserved for protein kinases, as exemplified by the well-characterized cyclin-dependent kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. More recently, sucrose nonfermenting-1 (SNF1), a kinase that modulates sugar metabolism in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), has been shown to be activated by three partially redundant kinases (for review, see Hardie, 2007). In animals, the SNF1 homolog, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), is activated by two kinases that are phylogenetically related to the yeast SNF1 activating kinases (Hardie, 2007). In plants, DNA sequence analysis and yeast complementation assays have implicated the GRIKs, which were originally identified as geminivirus Rep interacting kinases (Kong and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2002), as the upstream activators of SNF1-related kinases (SnRK1; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006; Hey et al., 2007). An analysis of the relationship between the GRIKs and SnRK1 activation represents an important first step in understanding the role of this putative protein kinase cascade in plants.

SnRK1, SNF1, and AMPK belong to a conserved family of protein kinases consisting of an α-catalytic subunit and regulatory β- and γ-subunits (for review, see Polge and Thomas, 2007). These kinases play central roles in regulating and coordinating carbon metabolism and energy balance in eukaryotes (for review, see Hardie et al., 1998; Halford et al., 2003, 2004; Hardie, 2007; Polge and Thomas, 2007; Baena-Gonzalez and Sheen, 2008). Metabolic stresses, such as sugar starvation and lack of light, stimulate SnRK1 activity (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). Suc-P synthase (SPS), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, nitrate reductase, and trehalose-6-P synthase are negatively regulated by SnRK1 phosphorylation (McMichael et al., 1995; Barker et al., 1996; Sugden et al., 1999b; Harthill et al., 2006), suggesting that SnRK1 modulates metabolism by phosphorylating key metabolic enzymes. However, SnRK1 is also thought to act as a master regulator of global gene expression in plants grown under starvation and energy deprivation conditions (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). The global expression profile resulting from SnRK1 overexpression positively correlates with treatments that limit energy and is inversely related to those associated with high-energy conditions (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). Many SnRK1-regulated genes are involved in plant primary and secondary metabolism, and catabolic pathways are generally up-regulated, while biosynthetic pathways are down-regulated (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007).

SnRK1 also impacts metabolic processes during development and disease. Studies in grains, legumes, and tuberous plants showed that loss of SnRK1 alters seed maturation, longevity, and germination, retards root growth, and reduces starch accumulation (Zhang et al., 2001; Lovas et al., 2003; Radchuk et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2007; Rosnoblet et al., 2007), while SnRK1 overexpression increases starch accumulation (McKibbin et al., 2006). Reduced expression of the SnRK1 β-subunit is responsible for sugar reallocation to roots during herbivore attack (Schwachtje et al., 2006). SnRK1 has also been implicated in resistance to geminivirus infection (Hao et al., 2003). However, there is evidence that SnRK1 has additional functions beyond modulating metabolism. Studies in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) showed that SnRK1 is essential for viability and that plants silenced for both SnRK1.1 and SnRK1.2 are severely stunted and impaired for flowering (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). Importantly, unlike Physcomitrella patens SnRK1 mutants (Thelander et al., 2004), these plants are not rescued by energy-surplus conditions, such as continuous light or growth medium containing 1% Suc. A number of SnRK1-responsive genes are associated with the cell division cycle and/or development, and some encode transcription factors and chromatin assembly/modifying factors (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007).

Phosphorylation of a conserved Thr residue in the activation loop of the kinase domain is an essential step during activation of SNF1 and AMPK. In budding yeast, three related and functionally redundant kinases, SAK1, TOS3, and ELM1, activate SNF1 (Hong et al., 2003; Nath et al., 2003; Sutherland et al., 2003). Sugars do not regulate these upstream kinases in yeast; instead, Glc promotes dephosphorylation of the activation loop by making it available to the protein phosphatase, Glc7-Reg1 (Rubenstein et al., 2008). In mammals, AMPK is activated by two upstream kinases, LKB1 and CaMKKβ (Hawley et al., 2003, 2005; Woods et al., 2003a, 2003b, 2005; Hurley et al., 2005). LKB1, which activates 12 AMPK-related kinases, is constitutively active (Lizcano et al., 2004), while CaMKKβ expression is associated with Ca2+ surges primarily in neural cells (Hawley et al., 2005). The LKB1-AMPK cascade plays roles in cell division, establishment of cell polarity, and senescence (for review, see Koh and Chung, 2007; Williams and Brenman, 2008). LKB1 has also been associated with cancer in humans (Alessi et al., 2006). A mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase can also functionally complement a yeast sak1Δ tos3Δ elm1Δ mutant and may activate AMPK in animals (Momcilovic et al., 2006).

GRIK1 and GRIK2 are the sole members of their kinase family in Arabidopsis, with the number of GRIK homologs ranging from one to three in other plant species (Kong and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2002; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006). In Arabidopsis, GRIK transcript levels vary minimally across different tissues and developmental stages, while GRIK proteins are detected exclusively in young tissues undergoing DNA synthesis and cell division, such as shoot apical meristems (SAMs), flower buds, and developing siliques (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006). The GRIK proteins also accumulate in geminivirus-infected cells that support DNA replication but not in healthy cells of mature leaves (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006). Studies using the proteasome inhibitor MG132 showed that the GRIK proteins are subject to proteasome-mediated degradation (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006).

The existence of a plant SnRK1 activating kinase was proposed several years ago (Sugden et al., 1999a). The Arabidopsis GRIK1 and GRIK2 proteins (also called SNAK2 and SNAK1, respectively) are phylogenetically related to yeast SAK1, TOS3, and ELM1 and mammalian LKB1 and CaMKKβ (Wang et al., 2003; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006; Hey et al., 2007). Each GRIK can complement a yeast sak1Δ tos3Δ elm1Δ triple mutant (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006; Hey et al., 2007). Together, these observations suggested that the GRIKs are upstream activators of SnRK1 in plants. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether GRIK1 and GRIK2 can phosphorylate and activate Arabidopsis SnRK1.

RESULTS

GRIK1 and GRIK2 Specifically Phosphorylate SnRK1

We first asked if the GRIKs specifically phosphorylate SnRK1 in vitro using recombinant Arabidopsis proteins. For the in vitro kinase assays, we produced wild-type GRIK1 and GRIK2 as glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged proteins. We also generated kinase-inactive forms of GRIK1(K137A) and GRIK2(K136A), which carried mutations in their ATP binding sites. The Arabidopsis genome encodes three SnRK1 α-subunit genes, including the functional SnRK1.1 and SnRK1.2 and unexpressed SnRK1.3 (Hrabak et al., 2003; Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). In this study, we focused on the N-terminal regions of SnRK1.1 (amino acids 1–341) and SnRK1.2 (amino acids 1–342), which include the kinase domains (KDs) and are catalytically active (Hao et al., 2003). We have designated these truncated proteins as SnRK1.1(KD) and SnRK1.2(KD), respectively. Both proteins include 22 amino acids at their C termini that are in the equivalent position to the AMPKα autoinhibitory region (Crute et al., 1998; Pang et al., 2007). However, it is unlikely that these residues are functionally equivalent in SnRK1 and AMPK because of their low sequence identity and lack of similarity in their predicted secondary structures. His6-tagged SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) and SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) were mutated in their ATP binding motifs to inhibit autophosphorylation activity. We also produced His6-tagged, inactive forms of full-length SnRK2.4(K33A) and the SnRK3.11 kinase domain (residues 1–334, K40A) as representatives of the functionally distinct SnRK2 and SnRK3 kinase subfamilies (Hrabak et al., 2003). All of the recombinant proteins were produced in Escherichia coli to preclude copurification of potential regulatory partners that are conserved across eukaryotes (Hardie, 2007; Polge and Thomas, 2007).

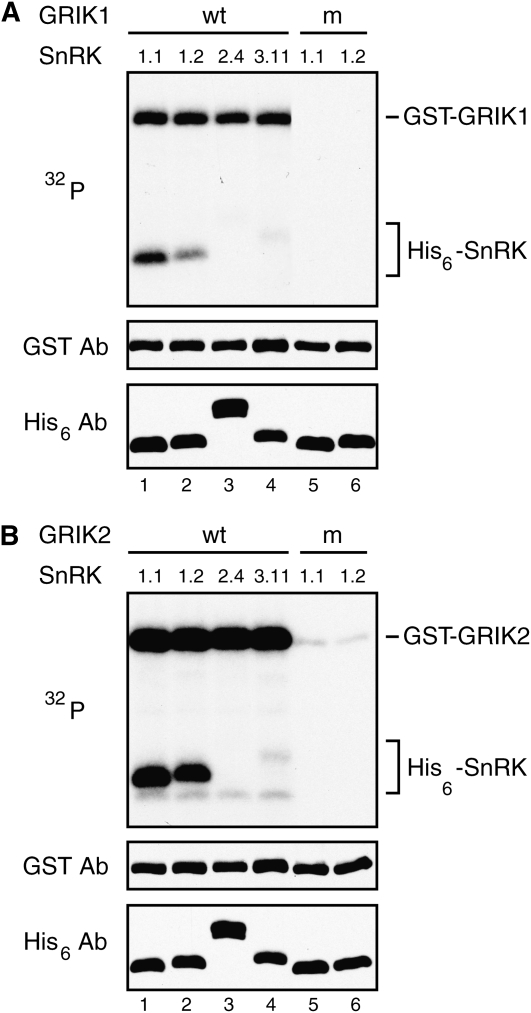

Various combinations of recombinant GRIK and SnRK proteins were incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP, and phosphorylation was monitored by autoradiography after SDS-PAGE and transfer of the proteins to nitrocellulose membranes. We detected GRIK autophosphorylation in the reactions containing wild-type GRIK1 (Fig. 1A, lanes 1–4) and GRIK2 (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–4) but not in those containing the corresponding kinase-inactive mutants (lanes 5 and 6). Both SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (lane 1) and SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) (lane 2) were radiolabeled in the presence of wild-type GRIK1 and GRIK2 but not in reactions containing the kinase-inactive GRIKs (lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, 32P-labeling of SnRK2.4(K33A) (lane 3) and SnRK3.11(KD, K40A) (lane 4) in the presence of the wild-type GRIKs was minimal. Together, these results demonstrated that GRIK1 and GRIK2 specifically phosphorylate the SnRK1 kinase domain.

Figure 1.

The GRIKs specifically phosphorylate SnRK1. A, GST-GRIK1 (wt, lanes 1–4) or the kinase-inactive GRIK1(K137A) (m, lanes 5 and 6) were analyzed using in vitro protein kinase assays. B, GST-GRIK2 (wt, lanes 1–4) or the kinase-inactive GRIK2(K136A) (m, lanes 5 and 6) were analyzed in equivalent assays. A and B, The different GRIKs were incubated with kinase-inactive kinase domains of His6-SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (lanes 1 and 5), His6-SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) (lanes 2 and 6), His6-SnRK3.11(KD, K40A) (lane 4), or kinase-inactive, full-length His6-SnRK2.4(K33A) (lane 3) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The top panels show 32P-labeled proteins visualized by autoradiography. The middle panels show total GST-GRIK proteins detected by immunoblotting with anti-GST antibodies, while the bottom panels correspond to total His6-SnRKs detected with an anti-His6 antibody.

GRIK1 and GRIK2 Phosphorylate a Thr Residue in the SnRK1 Activation Loop

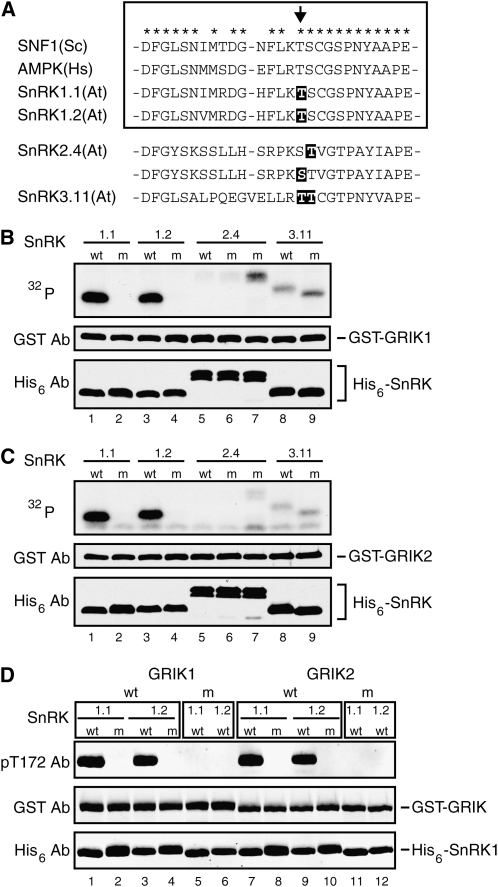

SNF1 and AMPK activating kinases phosphorylate a conserved Thr that is located 11 residues upstream of the invariant subdomain VIII Glu in the activation loops of SNF1 and AMPK (Hawley et al., 2003, 2005; Hong et al., 2003; Woods et al., 2003b, 2005; Shaw et al., 2004; Hurley et al., 2005). The activation loop sequences of SnRK1 are nearly identical to SNF1 and AMPK, including the conserved Thr residue (Fig. 2A). To determine if the GRIKs phosphorylate this Thr, we substituted Ala residues in place of the Thr residues in SnRK1.1(KD, T175A) and SnRK1.2(KD, T176A). Neither SnRK1 activation loop mutant (lanes 2 and 4) was radiolabeled in kinase assays containing wild-type GRIK1 (Fig. 2B) or GRIK2 (Fig. 2C) and [γ-32P]ATP, even though efficient phosphorylation of SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (lane 1) and SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) (lane 3) was detected in parallel reactions.

Figure 2.

The GRIKs phosphorylate a conserved Thr residue in the SnRK1 activation loop. A, Amino acid sequence alignment of the activation loops of yeast SNF1, human AMPKα, and Arabidopsis SnRK1.1, SnRK1.2, SnRK2.4, and SnRK3.11. The box encloses the SNF1 homologs, and the asterisks mark identical amino acids in the included sequences. The arrow indicates the conserved Thr residue. The highlighted residues were mutated to Ala residues to generate activation loop mutants. B and C, Protein phosphorylation assays containing GST-GRIK1 (B) or GST-GRIK2 (C) were performed using [γ-32P]ATP (top panels). The lanes contained His6-tagged wild-type (wt) activation loop SnRKs, including inactive kinase domains of SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (lane 1), SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) (lane 3), SnRK3.11(KD, K40A) (lane 8), or full-length SnRK2.4(KD, K33A) (lane 5) or activation loop mutant (m) forms of SnRKs, including SnRK1.1(KD, T175A) (lane 2), SnRK1.2(KD, T176A) (lane 4), SnRK2.4(K33A, S158A) (lane 6), SnRK2.4(K33A, T157A) (lane 7), and SnRK3.11(KD, K40A, T168A, T169A) (lane 9). D, Immunoblot kinase assays using antibodies against a human AMPKα phospho-T172 peptide with GST-GRIK1 (wt, lanes 1–4), kinase-inactive GST-GRIK1(K147A) (m, lanes 5 and 6), GST-GRIK2 (wt, lanes 7–10), or kinase-inactive GST-GRIK2(K136A) (m, lanes 11 and 12). The different GRIKs are enclosed by boxes. The substrates are inactive kinase domains with wild-type activation loop sequences (wt) of SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (lanes 1, 5, 7, and 11) or SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12) or kinase domains with mutant activation loop sequences (m) of SnRK1.1(KD, T175A) (lanes 2 and 8) or SnRK1.2(KD, T176A) (lanes 4 and 10), as indicated above the top panel. In B to D, total GST-GRIK and His6-SnRK were visualized using anti-GST (middle panels) and anti-His6 antibodies (bottom panels).

We then asked if antibodies that recognize a human AMPKα phospho-T172 activation loop peptide (pT172 antibodies) can cross-react with GRIK-phosphorylated recombinant SnRK1 on immunoblots (Fig. 2D). The pT172 antibodies recognized SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (compare lanes 1 and 5, and lanes 7 and 11) and SnRK1.2(KD, K49A) (compare lanes 3 and 6, and 9 and 12) after incubation with wild-type GRIKs but not the kinase-inactive forms. The pT172 antibodies also failed to detect SnRK1.1(KD, T175A) (lanes 2 and 8) or SnRK1.2(KD, T176A) (lanes 4 and 10) in reactions containing the wild-type GRIKs. These data established that the GRIKs phosphorylate the conserved Thr in the SnRK1 activation loop.

The activation loops of SnRK2 and SnRK3 kinases contain Thr or Ser residues at the equivalent positions to the SnRK1/SNF1/AMPK loops, but the flanking sequences are less conserved (Fig. 2A). We tested three SnRK2.4 and SnRK3.11 activation loop mutants with Ala substitutions in place of the Thr or Ser residues in the GRIK kinase assays using [γ-32P]ATP to monitor phosphorylation. SnRK2.4(K33A,S158A) (lane 6), SnRK2.4(K33A, T159A) (lane 7), and SnRK3.11(KD, K40A, T168A, T169A) (lane 9) were weakly labeled in the presence of GRIK1 (Fig. 2B) or GRIK2 (Fig. 2C). However, SnRK2.4(K33A) (lane 5) and SnRK3.11(KD, K40A) (lane 8), which have wild-type activation loop sequences, were also weakly labeled in parallel reactions, indicating that the GRIKs do not phosphorylate the activation loops of SnRK2.4 or SnRK3.11.

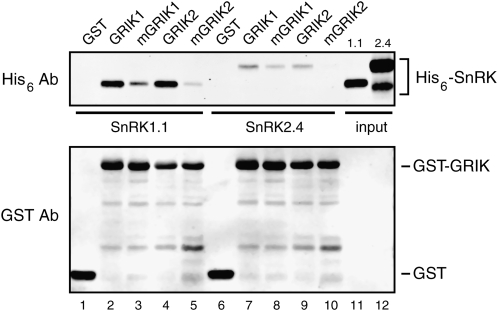

The specificity of a protein kinase for its substrate is in part reflected by its affinity for the unphosphorylated substrate (Ubersax and Ferrell, 2007). To investigate GRIK-SnRK1 interactions, we asked if His6-tagged, wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) copurified with GST-tagged GRIK1 or GRIK2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose resin. When equal molar concentrations of GST-GRIKs and SnRK1.1 were mixed, approximately 20% of the His6-SnRK1.1 was pulled down by the resin in the presence of GST-GRIK1 (Fig. 3, lane 2) or GST-GRIK2 (lane 4), indicating that SnRK1.1 had similar binding affinity for the two GRIKs. In contrast, <2% of His6-SnRK2.4 incubated with GST-tagged GRIK1 (lane 7) or GRIK2 (lane 9) was in the bound fraction. Neither SnRK1.1 nor SnRK2.4 was in the bound fraction in the GST control (lanes 1 and 6). Together, these results showed that the GRIKs form stable complexes with SnRK1.1 but not SnRK2.4 in vitro, consistent with their phosphorylation specificities. Interestingly, both kinase-inactive GRIK1(K137A) and GRIK2(K136A) displayed substantially less binding capacity for SnRK1 (lanes 3 and 5) relative to wild-type GRIKs, suggesting that the GRIK autophosphorylation site and/or the SnRK1 transphosphorylation site is important for the GRIK-SnRK1 interaction.

Figure 3.

The GRIKs interact with SnRK1.1. Equal concentrations (150 nm) of His6-tagged SnRK1.1 kinase domain (lanes 1–5) or full-length SnRK2.4 (lanes 6–10) were incubated with GST (lanes 1 and 6), GST-tagged GRIK1 (lanes 2 and 7), GST-tagged kinase-inactive GRIK1(K137A) (mGRIK1; lanes 3 and 8), GST-tagged GRIK2 (lanes 4 and 9), or GST-tagged kinase-inactive GRIK2(K136A) (mGRIK2; lanes 5 and 10). The protein mixtures were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose, and the bound fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblotting with antibodies to the His6 (top panel) or GST (bottom panel) tags. Aliquots equivalent to one-fourth of the input for His6-tagged SnRK1.1 (lane 11) and SnRK2.4 (lane 12) were included on the gels.

GRIK1 and GRIK2 Activate SnRK1

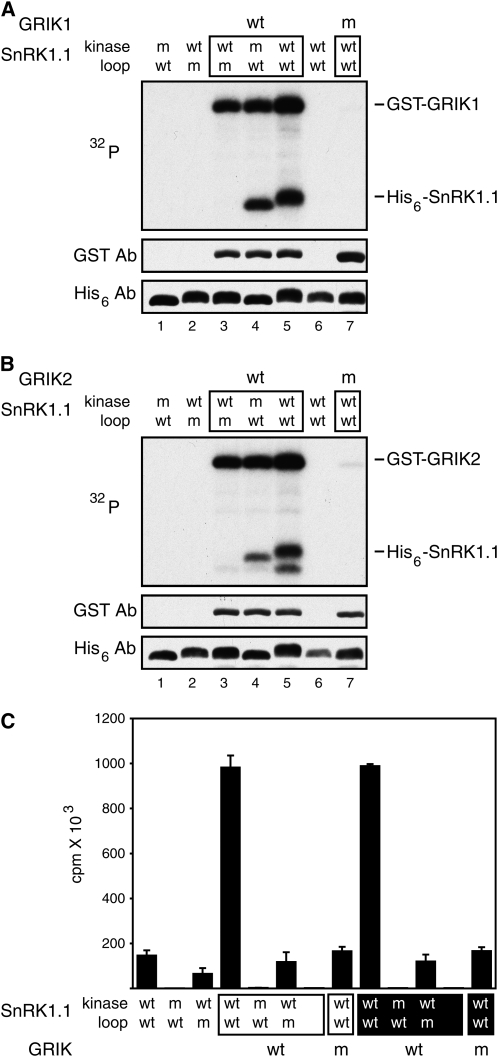

We asked if GRIK-catalyzed phosphorylation of SnRK1 impacts its kinase activity in vitro by examining the activity of His6-tagged, wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) in the presence or absence of functional GRIK. SnRK1.2(KD) was not included in these studies because of technical problems expressing the wild-type recombinant protein in E. coli. Initially, we examined the effect of GRIK1 (Fig. 4A) or GRIK2 (Fig. 4B) on SnRK1.1 activity in reactions containing [γ-32P]ATP by SDS-PAGE. Wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) was labeled in the presence of both wild-type GRIKs (lane 5), but no labeling was seen in reactions with mutant (lane 7) or no GRIK protein (lane 6), indicating that untreated, wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) was not active in the assay. Strikingly, wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) incorporated more label and displayed reduced mobility on SDS gels in comparison to the kinase domain mutant, SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (compare lanes 4 and 5), indicative of the presence of additional phosphate groups. The extra phosphate groups were not detected for the kinase-inactive SnRK1.1(KD, K48A) (lane 4). Thus, the reduced mobility of wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) was not due to sequential phosphorylation by the GRIKs and, instead, reflected its autophosphorylation activity. SnRK1.1(KD, T175A) was not labeled in the presence of functional GRIKs (lane 3), indicating that phosphorylation of the activation loop is required for SnRK1.1 autophosphorylation.

Figure 4.

The GRIKs activate SnRK1 kinase activity. A and B, Protein phosphorylation assays with wild-type (lanes 3–5) or kinase-inactive forms (lane 7) of GST-tagged GRIK1 (A) or GRIK2 (B) were performed using [γ-32P]ATP (top panels). The lanes contained the His6-tagged SnRK1.1 kinase domain (lanes 5–7) or the corresponding kinase-inactive mutant (K48A; lanes 1 and 4) or activation loop mutant (T175A; lanes 2 and 3). Total GST-GRIK and His6-SnRK1.1 were visualized using anti-GST (middle panels) and anti-His6 antibodies (bottom panels). C, His6-tagged wild-type (wt) SnRK1.1 kinase domain, its kinase-inactive form (m), or activation loop mutant (m) was incubated alone or in the presence of GST-tagged wild-type (wt) or kinase-inactive (m) GRIK1 or GRIK2. SnRK1 kinase activity was monitored by 32P-labeling of a peptide substrate derived from Suc-P synthase. The mean activities and sds for three experiments using different SnRK preparations are shown.

We next used an SnRK1 peptide substrate to measure the magnitude of the effect of GRIK-catalyzed phosphorylation on SnRK1 activity in vitro. The peptide was derived from spinach (Spinacia oleracea) SPS, which is inactivated by SnRK1 phosphorylation (Huber and Huber, 1996). Other studies established that the SPS peptide, KGRMRRISSVEMMK, is phosphorylated at S158 (underlined) in a Ca2+-independent manner by SnRK1 purified from spinach (Huber and Huber, 1996; Sugden et al., 1999b; Huang and Huber, 2001). Using filter binding assays to monitor 32P-labeling of the SPS peptide (Fig. 4C), we detected a low but measureable level of kinase activity for wild-type SnRK1.1(KD) by itself but not for the kinase-inactive SnRK1.1(KD, K48A). The activation loop mutant SnRK1.1(KD, T175A) had trace activity that was lower than its wild-type counterpart. When functional GRIK1 or GRIK2 was included in the reactions, wild-type SnRK1.1 activity was increased 7-fold, while no increase was observed in the reactions containing the kinase-inactive and activation loop mutant forms. Neither GRIK1 nor GRIK2 alone phosphorylated the SPS peptide, and their kinase-inactive forms did not impact wild-type SnRK1 activity. Taken together, these data established that the GRIKs activate SnRK1 by specifically phosphorylating the conserved Thr residue in its activation loop.

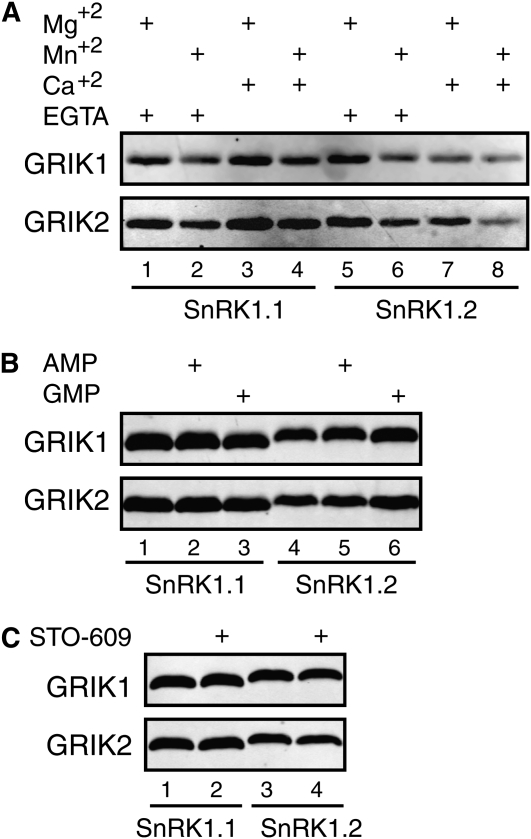

We examined the biochemical properties of GRIK phosphorylation of SnRK1 using the pT172 antibodies in immunoblot assays. For both GRIK1 and GRIK2, there was no detectable difference in SnRK1.1 phosphorylation in reactions containing Mg2+ and Mn2+ (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 1 and 2). The presence or absence of Ca2+ also had no effect on SnRK1.1 phosphorylation (compare lanes 3 and 4). We detected slight differences in SnRK1.2 phosphorylation in the presence or absence of the various divalent cations, with the highest level occurring in the presence of Mg2+ (lane 5). The 5′-AMP had no detectable effect on GRIK-mediated phosphorylation of SnRK1.1 and SnRK1.2 (Fig. 5B), consistent with previous reports that 5′-AMP enhances SnRK1 activity by inhibiting its dephosphorylation (Sugden et al., 1999a). SnRK1.1 and SnRK1.2 phosphorylation levels were also not impacted by 20 μm STO-609 (Fig. 5C), which inhibits CaMKKβ but not LKB1 activity in vitro (Hawley et al., 2005).

Figure 5.

Influence of cations, 5′-AMP, and STO-609 on GRIK activity. Phosphorylation assays containing GST-tagged GRIK1 (top) or GRIK2 (bottom) were performed in the presence of unlabeled ATP and detected by immunoblotting with antibodies against a human AMPKα phospho-T172 peptide. A, The reactions included 5 mm Mg2+ (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7), 5 mm Mn2+ (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8), 1 mm EGTA (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6), or 1 mm Ca2+ (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). Lanes 1 to 4 contained His6-SnRK1.1(KD, K48A), while lanes 5 to 8 contained His6-SnRK1.2(KD, K49A). B, The reactions contained no AMP or GMP (lanes 1 and 4), 0.5 mm AMP (lanes 2 and 5), or 0.5 mm GMP (lanes 3 and 6). Lanes 1 to 3 contained SnRK1.1, while lanes 4 to 6 contained SnRK1.2. C, The reactions were performed in the absence of STO-609 (lanes 1 and 3) or in the presence of 20 μm STO-609 (lanes 2 and 4). Lanes 1 and 2 contained SnRK1.1, while lanes 3 and 4 contained SnRK1.2.

GRIK Expression and SnRK1 Phosphorylation Overlap in Planta

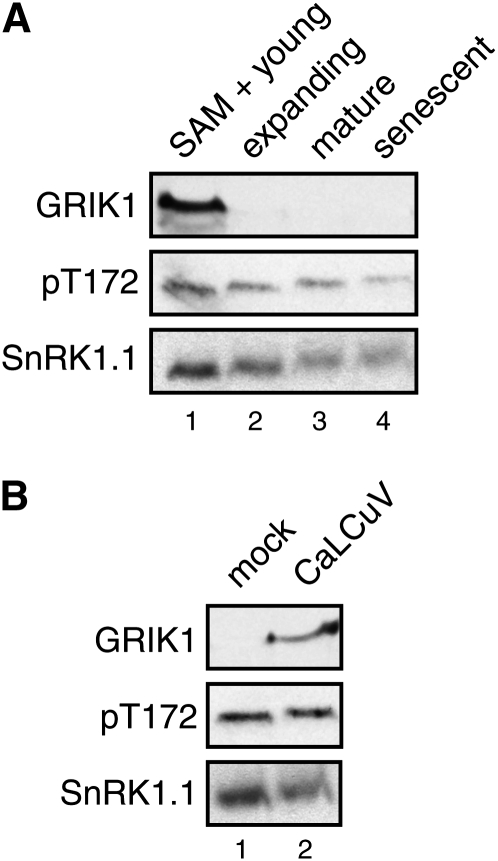

Earlier studies showed that GRIK1 and GRIK2 proteins only accumulate in the SAM and very young leaves (<0.5 cm in length) of healthy Arabidopsis rosette plants and in older leaves of geminivirus-infected plants (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006). Using the pT172 antibodies, we detected activated SnRK1 on immunoblots of protein extracts from the SAM and young leaves (Fig. 6A, lane 1) and leaves infected with Cabbage leaf curl virus (CaLCuV; Fig. 6B, lane 2). GRIK1 was also detected in these extracts by its antibodies. However, unlike GRIK1, activated SnRK1 was also found in extracts from expanding (Fig. 6A, lane 2), mature (lane 3), and senescing leaves (lane 4). The level of activated SnRK1 was similar in young, expanding, and mature leaves and slightly lower in senescing leaves. There was no detectable difference in the amount of activated SnRK1 in mock versus CaLCuV-infected leaves (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 1 and 2). Based on these results, we can conclude that the GRIK accumulation and activated SnRK1 patterns overlap, consistent with the GRIKs acting upstream of SnRK1 in young tissues and during geminivirus infection. Our data also suggested that a protein kinase(s) unrelated to the GRIKs phosphorylates SnRK1 in mature tissues.

Figure 6.

GRIK protein expression and SnRK1 phosphorylation overlap in planta. A, Total protein extracts from Arabidopsis SAM and young leaves (≤0.5 cm, lane 1), expanding leaves (0.5–2 cm, lane 2), fully expanded leaves (2–3 cm, lane 3), and senescing leaves (older than the fully expanded, lane 4) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. B, Total protein extracts from mock (lane 1) and CaLCuV-infected leaves (lane 2) were analyzed. Antibodies against the GRIK1 protein (top panels), a human AMPKα phospho-T172 peptide (middle panels), or SnRK1.1 (bottom panels) were used in A and B.

DISCUSSION

SnRK1 plays a central role in coordinating energy balance and nutrient metabolism in plants (for review, see Halford et al., 2003, 2004; Polge and Thomas, 2007; Baena-Gonzalez and Sheen, 2008). It promotes cellular catabolism and inhibits macromolecular synthesis in response to nutrient limitation and energy deprivation by directly regulating a number of enzymes related to carbon and nitrogen metabolism and by regulating the transcript levels of more than a thousand genes (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). The SnRK1 homologs, SNF1 and AMPK, are also major players in cellular processes related to energy and carbon source regulation in budding yeast and mammals (for review, see Hardie et al., 1998; Hardie, 2007). Both SNF1 and AMPK are activated by a phylogenetically related group of upstream kinases that phosphorylate conserved Thr residues in their activation loops (Hawley et al., 2003, 2005; Hong et al., 2003; Woods et al., 2003a, 2005; Shaw et al., 2004; Hurley et al., 2005). Earlier studies showed that SnRK1 is also phosphorylated at the equivalent Thr residue in vivo (Sugden et al., 1999a), but the identities of the plant kinases that activate SnRK1 have proven elusive. In this report, we demonstrate that the Arabidopsis kinases, GRIK1 and GRIK2, are SnRK1 activating kinases.

The SnRK family consists of three subfamilies: SnRK1, SnRK2, and SnRK3 (Hrabak et al., 2003). Although there is sequence similarity across the three groups, only the SnRK1s are orthologs of SNF1 and AMPK (Hrabak et al., 2003). Using recombinant proteins, we demonstrated that the GRIKs specifically phosphorylate SnRK1s and not SnRK2s or SnRK3s in vitro. Both SnRK1.1 and SnRK1.2 were efficiently phosphorylated in the presence of functional GRIK1 or GRIK2. The phosphorylated SnRK1 cross-reacted with the pT172 antibodies that were raised against a human AMPKα phospho-T172 activation loop peptide. Mutation of the corresponding Thr residues in the SnRK1 activation loops to Ala completely abolished phosphorylation, thereby establishing that they are the only residues in the SnRK1 kinase domains that are phosphorylated by the GRIKs. In contrast, SnRK2.4 and SnRK3.11 were poor GRIK substrates, and mutations in their activation loops had minimal impact on the outcome of the in vitro assays. We cannot formally rule out the possibility that other members of the SnRK2 or SnRK3 subfamilies are GRIK substrates, but this seems unlikely given the divergent nature of the activation loop sequences of the three SnRK subfamilies (Fig. 2A). The ability of the GRIKs to form stable protein complexes with SnRK1.1 but not SnRK2.4 in vitro also underscores their specificity.

SNF1 and AMPK are activated by phosphorylation of the Thr residues in their activation loops. Two lines of evidence indicated that GRIK-catalyzed phosphorylation of the Thr in the SnRK1.1 activation loop also resulted in kinase activation. First, SnRK1.1 autophosphorylation activity was detected only in the presence of the GRIKs. Second, SnRK1.1 phosphorylation of the SPS peptide, a cognate SnRK1 substrate (Huber and Huber, 1996; Sugden et al., 1999b; Huang and Huber, 2001), was elevated 7-fold in the presence of either GRIK1 or GRIK2. Both of these assays depended on the presence of the Thr residue in the SnRK1 activation loop, indicating that its phosphorylation by the GRIKs is essential for full activation. There are reports describing active SnRK1 in vitro in the absence of the GRIKs (Barker et al., 1996; Sugden et al., 1999b; Hao et al., 2003). These studies used either SnRK1 purified from plant tissues or produced in eukaryotic expression systems. In both cases, it is possible that the SnRK1 protein was already activated at the time of purification by endogenous upstream kinases, consistent with the observation that protein phosphatase treatment significantly reduced the SnRK1 activity isolated from spinach (Sugden et al., 1999a, 1999b). Our use of a bacterial expression system precluded prior activation of SnRK1 by endogenous kinases and enabled us to establish unequivocally that the GRIKs are SnRK1 activating kinases.

GRIK1 and GRIK2 are phylogenetically related to SNF1 and AMPK activating kinases and share some biochemical properties with them (Wang et al., 2003; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006; Hey et al., 2007). GRIK-mediated activation of SnRK1 is not affected by 5′-AMP, which greatly enhances AMPK activation by LKB1 and to lesser extent by CaMKKβ (Fig. 5; Woods et al., 2005). GRIK phosphorylation of SnRK1 was also not affected by Ca2+ (Fig. 5), which stimulates CaMKK activity in the presence of calmodulin (Hawley et al., 2005; Woods et al., 2005). The GRIKs and LKB1 kinase activities are not reduced by the protein kinase inhibitor STO-609, a property that distinguishes them from CaMKK, which is highly sensitive to STO-609 (Fig. 5; Hawley et al., 2005). However, LKB1 requires another protein, STRAD, for maximal AMPK phosphorylation (Shaw et al., 2004). We do not know if the GRIKs also have regulatory partners, but they are not dependent on other proteins to form stable complexes with unphosphorylated SnRK1 and are highly active by themselves in vitro (Fig. 3). Thus, the mechanisms that regulate the SnRK1/AMPK/SNF1 activating kinases are not necessarily conserved and may reflect divergent environmental interactions and developmental programs across eukaryotes.

The GRIK1 and GRIK2 proteins only accumulate in the Arabidopsis SAM and very young leaves, while phosphorylated SnRK1 occurs in tissues at all stages of leaf development (Fig. 6; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006). The different protein patterns are consistent with developmental regulation of SnRK1 activation, with the GRIKs activating SnRK1 during early development and an unrelated kinase(s) serving this function in mature tissues. This hypothesis is supported by the existence of multiple SNF1 and AMPK activating kinases in yeast and animals, respectively (Hardie, 2007). Furthermore, the involvement of TAK1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, in AMPK activation in mammals (Momcilovic et al., 2006) is consistent with the idea that diverse protein kinases can activate SnRK1 in plants. However, we cannot rule out that mature leaves contain low levels of the GRIK proteins sufficient to maintain a detectable fraction of activated SnRK1 or that young tissues express other SnRK1 activating kinases distinct from the GRIKs.

We also did not see a change in activated SnRK1 levels in geminivirus-infected mature leaves (Fig. 6B). Earlier studies showed that the GRIKs only accumulate in virus-positive cells (Kong and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2002; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006), which constitute <10% of the cells in a CaLCuV-infected Arabidopsis leaf (Ascencio-Ibañez et al., 2008). Thus, it was not unexpected that there was no detectable difference in the overall levels of phosphorylated SnRK1 in mock-inoculated and infected leaves. However, the levels of activated SnRK1 may vary between virus-positive cells and adjacent uninfected cells and differentially impact metabolic processes and host gene expression in the two cell populations. This idea is supported by the observation that geminiviruses encode two proteins that interact with the GRIK-SnRK1 cascade (Kong and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2002; Hao et al., 2003; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006).

SnRK1 has been implicated in a variety of plant processes ranging from stress responses to development. Multiple SnRK1 upstream kinases would provide a mechanism to differentially control SnRK1 signaling during these diverse processes. The GRIK-SnRK1 cascade may play a key regulatory role in young tissues and geminivirus-infected cells, both of which can support DNA replication and are likely to have high metabolic requirements. The cascade may ensure adequate energy and nutrient supplies to rapidly growing cells and impact plant cell cycle controls by modulating Suc levels (Riou-Khamlichi et al., 2000). In animals, LKB1 was originally identified as a tumor suppressor gene (Boudeau et al., 2003). The LKB1-AMPK pathway is required for normal mitotic processes and has been implicated in determining cell polarity (for review, see Koh and Chung, 2007; Williams and Brenman, 2008). In addition to phosphorylating and activating SnRK1 in young tissues, the GRIKs may influence substrate recruitment. We recently identified five Arabidopsis transcription factors that bind to the GRIKs in a yeast two-hybrid screen (W. Shen, M. Reyes, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin, unpublished data). The GRIKs may serve as bridging proteins between the transcription factors and SnRK1, which in turn may phosphorylate these factors. It is also possible that the GRIKs phosphorylate other proteins in addition to SnRK1 and impact developmental processes independent of SnRK1 signaling. Future experiments will address the roles of the GRIK-SnRK1 cascade and the GRIKs alone during development and geminivirus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth and Protein and RNA Preparations

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia-0 plants were grown in soil at 20°C in a Percival reach-in chamber with 8/16-h light/dark cycle and a light intensity of 15,000 Lux. Leaves at different developmental stages were collected from 6-week-old rosette plants. CaLCuV-infected leaves (0.5–1.5 cm long) were collected 12 d postinoculation from 7-week-old plants agroinoculated with pNSB1090 and pNSB1091, which contain partial tandem copies of CaLCuV A and B DNAs, respectively (Egelkrout et al., 2002). The mock control was from plants inoculated with an Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain carrying the corresponding empty cloning vector. Protein and RNA extraction procedures have been described previously (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006; Ascencio-Ibañez et al., 2008).

Plasmid Construction and Recombinant Protein Production

SnRK cDNA clones were obtained from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center stock numbers U24028 (SnRK1.1), U21346 (SnRK1.2), U24136 (SnRK2.4), and U24696 (SnRK3.11). The GRIK1 cDNA clone (Kong and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2002; Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006) has been described previously. A GRIK2 cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR of total RNA isolated from the SAM and young leaves of Arabidopsis Columbia-0 plants (Supplemental Materials and Methods S1). Detailed protocols for plasmid construction are described in Supplemental Materials and Methods S1. Site-directed mutants were generated with Stratagene's QuikChange system using complementary primer pairs containing designed mutations. For expression in Escherichia coli, the cDNAs were amplified using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and cloned into pET16b or pGEX-5X-3 for His6-tagged or GST-tagged proteins, respectively. Proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells after induction by 0.5 mm isopropylthio-β-galactoside for 16 h at 16°C. Bacteria were broken by sonication, and the tagged proteins were purified with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) or glutathione-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) resins according to manufacturers' instructions. Purified proteins were dialyzed against Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 140 mm NaCl, and 2.7 mm KCl) and stored in TBS with 1 mm dithiothreitol and 50% glycerol at −20°C.

Antibodies and Immunoblotting

GRIK1 polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbits using purified recombinant His6-GRIK1 as antigen (Cocalico Biologicals). The IgG fraction was purified using Protein G Sepharose 4B (Sigma-Aldrich). The GRIK2 C terminus peptide antibodies have been described previously (Shen and Hanley-Bowdoin, 2006). The human AMPKα phosphor-T172 peptide polyclonal antibodies (pT172 antibodies), GST polyclonal antibodies, and a His6 monoclonal antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, GE Healthcare, and CLONTECH, respectively. Proteins (50 μL per lane for plant proteins) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for antibody binding. Immunoblots of E. coli-produced proteins were visualized using fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies and an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). Immunoblots of plant proteins were visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescencent substrate (Pierce).

Protein Kinase Assay

For assays with protein substrates, a 50-μL reaction containing approximately 250 nm of the kinase and the substrate in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.2 mm ATP, and 0.1 μCi/μL [γ-32P]ATP was incubated at 30°C for 20 min. An equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added to stop the reaction, and a 40-μL aliquot was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The 32P-labeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography followed by immunoblotting of total proteins on the membrane. When pT172 antibodies were used to assay SnRK1 phosphorylation, only unlabeled ATP was included in the reaction, and phosphorylation was detected by immunoblotting. The kinase inhibitor STO-609 was from Sigma-Aldrich. When the plant SPS peptide acetyl-KGRMRRISSVEMMK (GenScript) was used as substrate (Huang and Huber, 2001), the reactions were stopped by transferring 40-μL aliquots to P81 filter paper discs, which were rinsed three times with 75 mm H3PO4 and dried. Bound radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter.

Protein-Protein Interaction Assay

GST-tagged proteins (150 nm) were incubated with His6-tagged proteins (150 nm) in 500 μL TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 at 22°C for 30 min followed by addition of 20 μL bed-volume of glutathione-Sepharose and incubation for another 30 min with rotation. The resin was washed three times in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. Bound proteins were eluted in 100 μL SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and 40-μL aliquots were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using GST and His6 antibodies.

Supplemental Materials

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table S1. Recombinant GRIK and SnRK proteins and their plasmids

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used in this study for mutagenesis, subcloning, and PCR.

Supplemental Materials and Methods S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. William F. Thompson and Ralph E. Dewey (North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC) for their critical comments on this manuscript and Dr. Elena Baena-González (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston) for performing immunoblotting with the SnRK1.1 antibodies that she provided.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. IBN–0235251 to L.H.-B.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Wei Shen (wshen@ncsu.edu).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alessi DR, Sakamoto K, Bayascas JR (2006) LKB1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu Rev Biochem 75 137–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascencio-Ibañez JT, Sozzani R, Lee TJ, Chu TM, Wolfinger RD, Cella R, Hanley-Bowdoin L (2008) Global analysis of Arabidopsis gene expression uncovers a complex array of changes impacting the pathogen response and cell cycle controls during geminivirus infection. Plant Physiol 148 436–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Gonzalez E, Rolland F, Thevelein JM, Sheen J (2007) A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448 938–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Gonzalez E, Sheen J (2008) Convergent energy and stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci 13 474–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JH, Slocombe SP, Ball KL, Hardie DG, Shewry PR, Halford NG (1996) Evidence that barley 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase kinase is a member of the sucrose nonfermenting-1-related protein kinase family. Plant Physiol 112 1141–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudeau J, Sapkotam G, Alessi DR (2003) LKB1, a protein kinase regulating cell proliferation and polarity. FEBS Lett 546 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crute BE, Seefeld K, Gamble J, Kemp BE, Witters LA (1998) Functional domains of the alpha1 catalytic subunit of the AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 273 35347–35354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelkrout E, Mariconti L, Cella R, Robertson D, Hanley-Bowdoin L (2002) The activity of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen promoter is differentially regulated by two E2F elements during plant development. Plant Cell 14 3225–3236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford NG, Hey S, Jhurreea D, Laurie S, McKibbin RS, Paul M, Zhang Y (2003) Metabolic signalling and carbon partitioning: role of SNF1-related (SnRK1) protein kinase. J Exp Bot 54 467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford NG, Hey S, Jhurreea D, Laurie S, McKibbin RS, Zhang Y, Paul MJ (2004) Highly conserved protein kinases involved in the regulation of carbon and amino acid metabolism. J Exp Bot 55 35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Wang H, Sunter G, Bisaro DM (2003) Geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins interact with and inactivate SNF1 kinase. Plant Cell 15 1034–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG (2007) AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: Conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 774–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Carling D, Carlson M (1998) The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu Rev Biochem 67 821–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harthill JE, Meek SE, Morrice N, Peggie MW, Borch J, Wong BH, Mackintosh C (2006) Phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding of Arabidopsis trehalose-phosphate synthase 5 in response to 2-deoxyglucose. Plant J 47 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, Mustard KJ, Udd L, Makela TP, Alessi DR, Hardie DG (2003) Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRAD alpha/beta and MO25 alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol 2 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, Edelman AM, Frenguelli BG, Hardie DG (2005) Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab 2 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey S, Mayerhofer H, Halford NG, Dickinson JR (2007) DNA sequences from Arabidopsis, which encode protein kinases and function as upstream regulators of SNF1 in yeast. J Biol Chem 282 10472–10479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SP, Leiper FC, Woods A, Carling D, Carlson M (2003) Activation of yeast SNF1 and mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase by upstream kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 8839–8843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabak EM, Chan CW, Gribskov M, Harper JF, Choi JH, Halford N, Kudla J, Luan S, Nimmo HG, Sussman MR, et al (2003) The Arabidopsis CDPK-SnRK superfamily of protein kinases. Plant Physiol 132 666–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JZ, Huber SC (2001) Phosphorylation of synthetic peptides by a CDPK and plant SNF1-related protein kinase. Influence of proline and basic amino acid residues at selected positions. Plant Cell Physiol 42 1079–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber SC, Huber JL (1996) Role and regulation of sucrose-phosphate synthase in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 47 431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RL, Anderson KA, Franzone JM, Kemp BE, Means AR, Witters LA (2005) The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases are AMP-activated protein kinase kinases. J Biol Chem 280 29060–29066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh H, Chung J (2007) AMPK links energy status to cell structure and mitosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 362 789–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong LJ, Hanley-Bowdoin L (2002) A geminivirus replication protein interacts with a protein kinase and a motor protein that display different expression patterns during plant development and infection. Plant Cell 14 1817–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizcano JM, Goransson O, Toth R, Deak M, Morrice NA, Boudeau J, Hawley SA, Udd L, Makela TP, Hardie DG, Alessi DR (2004) LKB1 is a master kinase that activates 13 kinases of the AMPK subfamily, including MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J 23 833–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovas A, Bimbo A, Szabo L, Banfalvi Z (2003) Antisense repression of StubGAL83 affects root and tuber development in potato. Plant J 33 139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CA, Lin CC, Lee KW, Chen JL, Huang LF, Ho SL, Liu HJ, Hsing YI, Yu SM (2007) The SnRK1A protein kinase plays a key role in sugar signaling during germination and seedling growth of rice. Plant Cell 19 2484–2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin RS, Muttucumaru N, Paul MJ, Powers SJ, Burrell MM, Coates S, Purcell PC, Tiessen A, Geigenberger P, Halford NG (2006) Production of high-starch, low-glucose potatoes through over-expression of the metabolic regulator SnRK1. Plant Biotechnol J 4 409–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael RW Jr, Bachmann M, Huber SC (1995) Spinach leaf sucrose-phosphate synthase and nitrate reductase are phosphorylated/inactivated by multiple protein kinases in vitro. Plant Physiol 108 1077–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momcilovic M, Hong SP, Carlson M (2006) Mammalian TAK1 activates SNF1 protein kinase in yeast and phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro. J Biol Chem 281 25336–25343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath N, McCartney RR, Schmidt MC (2003) Yeast Pak1 kinase associates with and activates SNF1. Mol Cell Biol 23 3909–3917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang T, Xiong B, Li JY, Qiu BY, Jin GZ, Shen JK, Li J (2007) Conserved alpha-helix acts as autoinhibitory sequence in AMP-activated protein kinase alpha subunits. J Biol Chem 282 495–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polge C, Thomas M (2007) SNF1/AMPK/SnRK1 kinases, global regulators at the heart of energy control? Trends Plant Sci 12 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radchuk R, Radchuk V, Weschke W, Borisjuk L, Weber H (2006) Repressing the expression of the SUCROSE NONFERMENTING-1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE gene in pea embryo causes pleiotropic defects of maturation similar to an abscisic acid-insensitive phenotype. Plant Physiol 140 263–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou-Khamlichi C, Menges M, Healy JMS, Murray JAH (2000) Sugar control of the plant cell cycle: differential regulation of Arabidopsis D-type cyclin gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 20 4513–4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosnoblet C, Aubry C, Leprince O, Vu BL, Rogniaux H, Buitink J (2007) The regulatory gamma subunit SNF4b of the sucrose non-fermenting-related kinase complex is involved in longevity and stachyose accumulation during maturation of Medicago truncatula seeds. Plant J 51 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein EM, McCartney RR, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Shirra MK, Arndt KM, Schmidt MC (2008) Access denied: SNF1 activation loop phosphorylation is controlled by availability of the phosphorylated threonine 210 to the PP1 phosphatase. J Biol Chem 283 222–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwachtje J, Minchin PE, Jahnke S, van Dongen JT, Schittko U, Baldwin IT (2006) SNF1-related kinases allow plants to tolerate herbivory by allocating carbon to roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 12935–12940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA, Cantley LC (2004) The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 3329–3335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Hanley-Bowdoin L (2006) Geminivirus infection up-regulates the expression of two Arabidopsis protein kinases related to yeast SNF1- and mammalian AMPK-activating kinases. Plant Physiol 142 1642–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden C, Crawford RM, Halford NG, Hardie DG (1999. a) Regulation of spinach SNF1-related (SnRK1) kinases by protein kinases and phosphatases is associated with phosphorylation of the T loop and is regulated by 5′-AMP. Plant J 19 433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden C, Donaghy PG, Halford NG, Hardie DG (1999. b) Two SNF1-related protein kinases from spinach leaf phosphorylate and inactivate 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, nitrate reductase, and sucrose phosphate synthase in vitro. Plant Physiol 120 257–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland CM, Hawley SA, McCartney RR, Leech A, Stark MJ, Schmidt MC, Hardie DG (2003) Elm1p is one of three upstream kinases for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF1 complex. Curr Biol 13 1299–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelander M, Olsson T, Ronne H (2004) SNF1-related protein kinase 1 is needed for growth in a normal day-night light cycle. EMBO J 23 1900–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubersax JA, Ferrell JE Jr (2007) Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 530–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Harper JF, Gribskov M (2003) Systematic trans-genomic comparison of protein kinases between Arabidopsis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plant Physiol 132 2152–2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Brenman JE (2008) LKB1 and AMPK in cell polarity and division. Trends Cell Biol 18 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Dickerson K, Heath R, Hong SP, Momcilovic M, Johnstone SR, Carlson M, Carling D (2005) Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metab 2 21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Johnstone SR, Dickerson K, Leiper FC, Fryer LG, Neumann D, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Carlson M, Carling D (2003. a) LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol 13 2004–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Vertommen D, Neumann D, Turk R, Bayliss J, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Carling D, Rider MH (2003. b) Identification of phosphorylation sites in AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) for upstream AMPK kinases and study of their roles by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem 278 28434–28442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shewry PR, Jones H, Barcelo P, Lazzeri PA, Halford NG (2001) Expression of antisense SnRK1 protein kinase sequence causes abnormal pollen development and male sterility in transgenic barley. Plant J 28 431–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.