Abstract

Quantifying and rating the impairments due to mental and behavior disorders are difficult for their own characteristics. Korean Academy of Medical Sciences (KAMS) is developing guidelines of rating impairment in mental and behavioral disorders based on Korean Neuropsychiatric Association (KNPA)'s new guidelines. We compared the new KNPA's guidelines and the American Medical Association (AMA)'s 6th Guides in assessing impairment due to mental and behavioral disorders to develop new guidelines of KAMS. Two guidelines are different in diagnosing system, applicable disorders, qualification of assessors, application of scales, contents of assessment and rate of impairment of the whole person. Both AMA's and the proposed guidelines have individual merits and characteristics. There is a limitation in using the 6th AMA's Guides in Korean situation. However to improve objectivity in Korean assessment of psychiatric impairment, the new AMA's Guides can serve as a good reference.

Keywords: Disability Evaluation, Mental Disorders, Behavioral Symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Quantifying the impairments due to mental and behavior disorders are difficult for their own characteristics. Therefore the assessors are prone to rate the impairment variously according to their experience and attitude toward impairment. Recently as stigmas of psychiatric disorders have been decreased, social demands about psychiatric evaluation due to various accidents or disorders are increased. Because previous guidelines or tools were not fully reflects characteristics of psychiatric disorders, there were too many rooms to involve subjective decision in assessing psychiatric impairment.

There has been an effort to decrease divergence in evaluating psychiatric impairment. Ahn et al. (1) pointed out the problems of previous psychiatric evaluation for depending too much on subjectivity and emphasized objective observation through psychiatric scales or tools. Jung et al. (2) insisted that there were some needs to make up vagueness of recent public evaluation guidelines including Law for Work Disability Compensation and Act of National Compensation. The Korean Neuropsychiatric Association (KNPA) published Guidelines to Evaluate Mental and Behavior disorders for compensating such weakness of previous guidelines (3).

The chapter of mental and behavior disorders in 'Guides to the Evaluation Permanent Impairment' sixth edition (4) of American Medical Association (AMA) was vastly reedited and the pages were more than doubled since the fifth edition.

Outstanding points of the AMA's latest edition are assessing impairment severity and using psychiatric rating scales. In the 5th edition, there were only 5 classes of impairment depends on activity of daily living, social functions, concentration and pace, and deterioration or decompensation in work or work-like settings, because of subjectivity of assessing psychiatric impairment. However, in the 6th edition, they suggest using 0 to 50% impairment of the whole person with 3 psychiatric rating scales; brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS), global assessment of functioning scale (GAF) and psychiatric impairment rating scale (PIRS). Issues about using such rating scales in Korea will be discussed later in this article, but the efforts to objectify and quantify psychiatric impairment are very necessary in Korean situation. Also they define 'Maximal Medical Improvement', and suggest to aware the possibility of malingering in the 6th edition.

The Korean Academy of Medical Sciences (KAMS) is developing a guideline of rating impairment in mental and behavioral disorders based on the KNPA's new guideline. In this context, we compare the AMA and KNPA guidelines about evaluation of mental and behavior disorders in this article.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We compared KNPA's new guideline sand AMA's 6th Guides in assessing impairment due to mental and behavioral disorders to develop new guidelines of KAMS by the committee of KAMS. Through these comparisons, we could suggest issues and modification in our new guidelines.

RESULTS

Psychiatric diagnosis and impairment

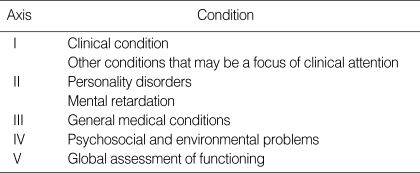

The diagnoses of AMA's 6th Guides are basically made by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (5) which published by American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV categorizes mental disorders to 17 classes. One of the important aspects of DSM-IV is multiaxial evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Multiaxial system of the DSM-IV

DSM-IV, diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition.

Diagnoses of KNPA's guidelines are based on 10th edition of International Classification of Diseases and Health Problems (ICD-10) (6). ICD-10 was published by World Health Organization in 1992, and classified mental disorders in 10 categories. Though DSM-IV was designed to be compatible with ICD-10, two diagnostic systems are different in some details. For example, in case of post-traumatic stress disorder, DSM-IV is emphasizing personal-experience of the patient, but ICD-10 considers actual severity of the accident as the most important factor in diagnosing. Such a subtle difference between two diagnostic systems causes confusion in evaluation of mental and behavioral disorders.

One of the characteristics in AMA's new guidelines is limiting applicable diseases. These guidelines can be used only in mood disorders (major depressive disorders and bipolar disorders), anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder) and psychotic disorder (schizophrenia and related disorders). Especially it excludes pain related mental symptoms, somatization disorders, dissociative disorders, personality disorders, psychosexual disorders, factitious disorders and substance-related disorders. They exclude these disorders on the grounds that the symptoms of them are very subtle, easily influenced by previous personal character, and changeable due to legal issues.

Although there are also frequent medicolegal issues about these disorders in Korea, we do not have exclusion criteria like AMA's. Therefore we should reconsider about approving permanent impairment in these disorders easily.

AMA's 6th edition recommends to evaluate mental symptoms manifested from dementia due to various etiology and delirium in chapter 13-central and peripheral nervous system. However our new guidelines include such disorders because it can not be divided precisely as organic disorders and psychiatric disorders, and only psychiatrists can evaluate impairment of both disorders in Korea. This issue is fully reflected in new Disability Law and Law of Work related Compensation.

Assessing psychiatric and psychological issue

AMA's 6th edition suggests using psychiatric rating scales in each evaluation areas. It includes 4 areas which are personality and symptom assessment, intellectual assessment, academic assessment and neuropsychological evaluation.

Committee of KNPA had discussions about using rating scales in assessing impairment. However many psychiatrists opposed this issue because of diversity of psychiatric symptoms and lack of standardized scales in Korea. The previous KNPA guidelines contained proclamatory comments like "must assess global function level and detailed items about contents and severities of symptoms and impairments, and use appropriate psychiatric rating scales for these purposes" (7). It needs further study to use rating scales suggested in AMA Guides in assessing psychiatric impairment in Korea.

Also, a neuropsychological test without standardization should not be used in assessing impairment alone. AMA's new Guides strongly recommend checking the scales by clinicians who assess impairment of mental and behavioral disorders as follows.

The psychological test should be done by a trained examiner and not merely cosigned by supervising psychologists.

Test findings should be internally consistent.

The examiners should document which materials were reviewed, and test results should be consistent with information in the records.

Baseline/premorbid level of function of the patient should be adequately explored and documented.

Appropriate normative data should be listed for each test.

The set of psychological tests should contain 2 or more validity tests of the symptoms.

The neuropsychological test has an important role in evaluating mental and behavioral impairment in Korea. It enables us to guarantee the objective evidences of symptoms which observed by clinicians and to make up for the missed point of clinical assessments. But qualification of examiners is still obscure in Korea because of lack of sufficient qualified examiners and unsettled medical fee. For decreasing the effects of erroneous results by unqualified examiners, at least there should be a qualification of examiners in assessing the impairment in pivotal area such as brain injury or severe mental illness. KNPA guidelines also comment 'evident organic lesion and impairment is only confirmed by objective test (neuroimaging or neuropsychological test)' and it means that objective test should be used as evidence of symptoms observed by clinicians.

AMA's another emphasizing part is that the result of neuropsychological test is not a pathognomonic sign of brain diseases.

Qualification of the assessor

In the KNPA's guideline, only psychiatrists or neuropsychiatrists can assess the psychiatric impairment and also it recommends that the assessors should take proper education and training about assessment. The AMA Guides, 6th edition limits the qualification of the assessors more clearly than our guidelines. They recommend that the clinicians who assess the impairment of the patients should be neutral and free from stigma. The psychiatrists are easy to be in unconditioned positive regard because psychiatric treatment starts from empathic and accepting attitude of therapist. Therefore the AMA Guides strongly recommends that the clinicians or psychologists who treated the patient should not assess the impairment for legal purpose. In Korea, the same rule is kept in the evaluation for the court, and is begun to comply with in assessment for severe impairment for the national pension. However assessment for work related compensation and private insurance needs more detailed qualification for assessors.

Contents of assessment

The KNPA's guideline recommends that not only precise diagnosis which is determined according to areas of impairment and diagnostic systems but also objective and rational evidences should be presented.

Medical records and the results of examination at the onset of disorders.

Medical records and the results of examination before the onset of disorders.

Data helpful in judging adjustment level before the onset of disorders; school registers, school reports and job reports.

Data helpful in judging adjustment level after the onset of disorders; school registers, school reports and job reports.

Data from insurance company or medical insurance.

Data from family or neighbors.

If there are not enough objective evidences, clinicians should assess the impairment more carefully. The AMA Guides are more concrete and specific than the KNPA's. The principles of assessment of psychiatric impairment in AMA Guides 6th edition are as follows.

Assess the structure of personality, especially pay close attention to antisocial, borderline, histrionic, narcisstic, passive-dependent, passive-aggressive personality traits.

Evaluate basic defense system.

Examine past and current drug abuse affecting mental and behavioral disorders.

Search for past legal problems.

Pay attention to exaggerating tendency.

Confirm military records.

Assess the patient's motivation of returning to workplace.

Assess the patient's attitude toward insurance companies or employers.

Assess the effect of legal process on patient's returning to workplace

Verify whether proper biological treatment including pharmacotherapy is offered.

The contents of assessment in AMA's 6th Guides can be a good reference in developing our specific guidelines in Korean situation.

Assessment scales

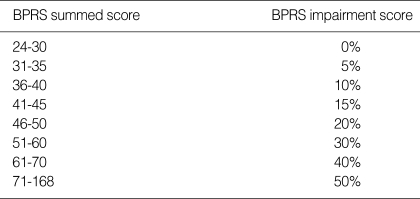

The AMA Guides (6th edition) proposes three psychiatric rating scales in assessing psychiatric impairment. The first one is BPRS which was developed in 1962 by Overall and Gorham. It has 24 items including the first 14 subjective items and the last 10 objective items (8). In assessing impairment severity, the patients are classified as 8 classes based on summed scores. The rate of impairment is divided from 0% to 50% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Impairment score of brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS)

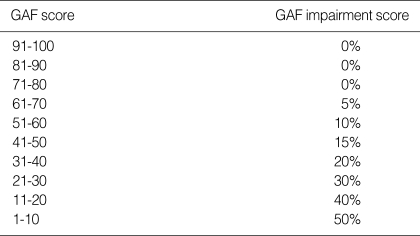

The second rating scale is GAF. Luborsky developed this tool in 1962 for diagnosis and statistics in psychiatric disorders (9). GAF assesses only psychological, social and occupational function. One of main problems in GAF is discrepancy among psychological, social and occupational function (10). The general rule is taking lowest function among three areas, and there are tendency to emphasize psychological function in clinical situation (11). These tendencies arouse some objections in using GAF in assessing psychiatric impairment (12). In Korea, GAF scores divided the impaired patients into three classes in assessing impairment rate; lower than 40, from 41 to 50, from 51 to 60. In the AMA Guides 6th edition, they rate the impairment below 70 as 5% of impairment scores (Table 3). Because there are controversial issues in impairment scores matching GAF scores, the KNPA's new guideline avoids using GAF scores.

Table 3.

Impairment score of global assessment of functioning scale (GAF)

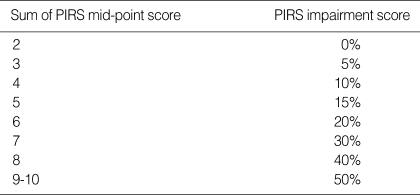

The last scale is psychiatric impairment rating scale (PIRS) which was developed in 2001 by J. Parmegiani and D. Lovell. It evaluates behavioral problems due to psychiatric symptoms in 5 areas; 1) role function, social and recreational activities, 2) travel, 3) interpersonal relationships, 4) concentration, persistence, pace, 5) resilience, employability. Sum of midpoints of 5 areas are used to rate impairment with 5-10% intervals (Table 4).

Table 4.

Impairment score of psychiatric impairment rating score (PIRS)

Three psychiatric rating scales in the AMA Guides evaluate the impairment in three viewpoints, severity of symptoms with BPRS, role function with PIRS and impairment rate in both aspects with GAF. They suggest to rate the psychiatric impairment with mid-points of rates in three scales. The three scales are enough to assess the impairment in disorders of the AMA Guides, but they have some limitation in evaluating various psychiatric and behavioral symptoms in Korean situation. Also we have approved 85% impairment of the whole person in mental and behavioral disorders nowadays. Limiting the rate of psychiatric impairment to 50% of the whole person can not be acceptable in culture of Korea.

DISCUSSION

The AMA Guides 6th edition was improved to detailed and systematized evaluation of psychiatric impairment. Objectifying the rate of impairment with three psychiatric rating scales was the most important advancement. In Korea, we also developed guidelines which tried to exclude the vagueness and subjectivity of assessment of the impairment due to mental and behavioral disorders.

The KNPA's new guideline is as follows compared to the AMA's 6th edition.

For diagnosing systems, AMA uses DSM-VI systems, but we refer ICD-10.

The AMA Guides excludes some disorders which are easily influenced by personal and social factors, but we assessed all psychiatric disorders but substance-related disorders comprehensively.

The AMA Guides limits the qualification of the examiners of clinical psychological test, but we do not have any comments about qualification.

The AMA Guides excludes the clinicians who treated the patients for assessors of impairment in legal purpose, but we do not have any comments about such limitation.

The AMA Guides emphasizes more thorough investigation about personality of the patients and profit in compensation than us.

The AMA Guides suggests using psychiatric rating scales in assessment, but we give concrete examples centering symptoms, social adjustment and occupational function.

The AMA Guides limits the rate of psychiatric impairment to 50% impairment of the whole person, but we approved 100% impairment of the whole person in psychiatric impairment.

Both AMA and KNPA guidelines have individual merits and characteristics. There are some limitations in using the 6th AMA Guides in Korean situation. However to improve objectivity in Korean assessment of psychiatric impairment, the new AMA's Guides can serve as a good reference.

References

- 1.Ahn DH, Kim YC, Rho SH, Park KC, Seo DW, Jung HY. The evaluation of mental and behavioral disabilities. Seoul: Han Yang University Institute of Mental health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung HY, Han SW, Han SH. Evaluation of sequela and physical disability in traumatic brain injury: focus on mental and behavioral problems. Korean Jungang Med J. 1999;64:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryu SG, Jung HY, Ryu SH, Jung IK, Ahn DH, Kim YC, Choi KS, Lee KU, Woo JM. Guides to the evaluation of neuropsychiatric impairment. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2007;46:332–341. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rondinelli RD, Genovese E, Brigham CR. Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment. 6th ed. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee BY. 10 Classification of mental and behavioral disorders, clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Seoul: Il Jo Gak; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim CY. Psychiatric assessment instruments. Seoul: Hana Medical Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bech P, Larsen JK, Andersen J. The BPRS: psychometric developments. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luborsky L. Clinician's judgment of mental health. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1962;7:407–417. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1962.01720060019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman HH. Do you walk to school, or do you carry your lunch? Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:419. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moos RH, Nichol AC, Moos BS. Global assessment of functioning ratings and the allocation and outcomes of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:730–737. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niv N, Cohen AN, Sullivan G, Young AS. The MIRECC version of the global assessment of functioning scale: reliability and validity. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:529–535. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]