Indeed, while it is not impossible that a particular will agrees with the general will on some point, it is in any event impossible for this agreement to be lasting and constant; for the particular will tends, by its very nature, to partiality, and the general will tends to equality.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The conceptualization of medicine as a unique field of endeavor is swiftly changing, and the change involves complex social and technological factors. The concept of “medicine” is dynamic: the range of ailments dealt with by medical care changes, as does the range of therapeutic options. In addition, with the growth in income and education, consumers—especially those in the middle- and upper-income brackets who are self-reliant and stress individualism—expect an increasing diversity of medical care and institutions to supply it (Antonovsky 1987; Schneider, Dennerlein, Kose, et al. 1992; Williams and Calnan 1996). Hence, the character of the product or service offered and demanded is becoming more difficult to determine, especially in socioeconomically advanced communities.

In developed nations, the absence of a correlation between a country's expenditures on medical care and the population's health as measured by morbidity and mortality complicates the issue further, since the association between health and the level of investment in medical care is not always as might be expected (OECD 1990). This issue becomes even murkier in the case of care that is a public entitlement, because the state or society, in addition to the provider and the patient, has a say in both the level of financing and the nature of the entitlement. Consequently, what the state and what the individual or profession may deem necessary and worthy may not be the same. Efforts to tailor public entitlement to care on the basis of its “social efficiency” have led nowhere (Londoño 2000). As a result, developed nations must constantly seek a balance between the perceived need for medical care and the acceptable level of national (public plus private) expenditure on that care.

Reform efforts were started in the 1980s to reduce the monopoly power of providers and thereby increase both the government's and the consumer's influence on the form of care, if not on its nature. In a wide range of publicly supported health systems under managed or regulated competition, consumers may now choose among competing budget-holding or fund-holding third-party buyers, for example, sickness funds in the Netherlands (van de Ven and Schut 2000), Israel (Chernichovsky and Chinitz 1995), Russia (Chernichovsky, Barnum, and Potapchik 1996) and Colombia (Londonño 2000); community providers in the United Kingdom (Secretary of State for Health 1998); and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (Schlesinger 1997) in the United States. In such cases, public funds “follow” consumers to the budget holder of their choice.

The reformers assumed that in all cases, the fund holders would be cost- and quality-conscious buyers of care on behalf of their members. Even the United States’ managed competition approach rested on the premise that the “plans” would be responsive to consumers and would supply the information needed to make a wise choice (Schlesinger 1997). That is, they assumed that all institutions organizing and managing the consumption of care (OMCC institutions) would represent their members when both healthy and sick.

This was too optimistic. Although consumers now have more choices, they still have little direct control over the nature of care they receive under public entitlement. In those countries where the functions of the budget-holding institutions that organize and manage the consumption of care (Chernichovsky 1995a) and those of the institutions that provide the care have clearly split, for example, in the Netherlands and Israel, power has shifted mainly from the providers to the government, on the one hand, and to budget holders like OMCC institutions, on the other. Where the split has not been so clear, for example, in the United Kingdom, the last British reform shifted power from consultants in hospitals to mainly community providers (primary care groups or trusts). Institutionally and politically, the reforms gave rise to a fourth agent, the OMCC institution, in addition to the government, providers, and consumers. While the various types of OMCC institutions have developed their own interests, the roles of government and providers vis-à-vis those institutions have become blurred. For consumers, however, choice—or empowerment or any other term for greater user control over the public entitlement and its production—has remained in the hands of politicians and health care providers (IHE 1996;Segal 1998). Indeed, given the nature of health systems, individual consumers, unlike producers or the government, lack the resources to exert their collective power (Rodwin 1996).

A well-defined institutional channel for consumer choice regarding public entitlement and its production is the missing element in health system reform, and its absence threatens the viability and raison d'être of the publicly supported health system that is the focus of this discussion. In developed nations where supply-side constraints have mounted, the absence of an outlet for consumers’ expectations and preferences has led to their dissatisfaction and pressure on both private and public spending. Where private financing is accepted as part of the publicly supported system (e.g., in Australia and France), there are extra pressures on the rising cost of care. Where it is not permitted (e.g., in Canada and Israel), there are pressures inside the system for under-the-table pay (e.g., Israel) and on the public budget. Such pressures foil efforts to promote equity and to control aggregate medical care spending, which are the main goals of public involvement in the health system. Indeed, the role of private or supplementary insurance as an outlet for “extra” demands by consumers has become a thorny issue in at least two nations, the Netherlands and Israel, whose reforms are based on OMCC institutions (Chernichovsky 1998;van de Ven and Schut 2000).

The challenge in the developing nations is different: building a universal and comprehensive health system out of a fragmented one. The support of affluent groups for a universal system is both a financial and a political condition for meeting that challenge. Vital to this support is a system that enables those groups to bring their demands to a publicly supported system.

A Swedish commission looking at the health services of the future stressed that “if the power struggle between the system and citizens over the right to determine who is in control of the health services is to be resolved in the citizen's favor, the citizen must possess an instrument of power able to work against the system” (IHE 1996, p. 5). The discussion that follows does not advocate working “against the system” but rather promotes one in which multiple models of public entitlement and its delivery coexist. Such models—implemented through consumer-based OMCC institutions—support pluralism, informed choice, and consumer power.

The emerging paradigm in the reform of systems is characterized by the rise of competing OMCC institutions. Those institutions can develop further to offer choice and become better representatives of their members, while the roles of the other agents, particularly the government, should be better defined.

This approach is a modification of Schlesinger's (1997) “strategy of countervailing agency” that views the (American) competitive health plan as an agent for society and the health professional as an agent for the patient. My approach views government as an agent representing the paying society or citizens; OMCC institutions—possibly “plans” in the American context—as representing their members (rather than “citizens”) as individual clients and patients; and providers as representing themselves. These roles and interests are interwoven and may shift, as citizens are also consumers, and consumers can become patients. Furthermore, providers’ interests are not divorced from the others’ and vice versa. The challenge is establishing well-defined institutions or political power bases while creating a constructive balance between them.

Public Choice and Entitlement

Public entitlement—matching the need for care with the level of national expenditure required to fulfill that need—can be defined in accordance with different approaches to balancing limited resources with the attainment of health system objectives: better health, equity and social justice, cost control and macroeconomic efficiency (to minimize the potentially adverse impact of health care expenditures on the economy), efficiency in the production of quality care, and clients’ satisfaction with the care. Each approach reflects the relative importance of a health system's different objectives and its specific characteristics.

At one extreme is a system based largely on free-market principles. The amount and type of care produced generally reflect some combination of expert (i.e., provider) opinion regarding the appropriate care and the patient's ability and willingness to pay for it. These two considerations—what treatment is appropriate and the patient's ability to pay for it—may not be independent of each other; that is, the provider may prescribe on the basis of the patient's ability to pay. In this case, the cost and nature of the care are not determined in advance based only on the type and severity of illness; rather, they are determined in the marketplace when patients interact with providers. Of the developed nations, the private segment of the American health system is the best example of this approach. However, the extent to which the care offered is determined by the patients’ interaction with their doctors has changed significantly with the evolution of managed care.

At the other extreme is the solution based on the principles of the centralized and fully integrated public or state system, in which the state finances, organizes, and manages the consumption and provision of publicly supported care. In this case, public or socially perceived needs are expressed through universal entitlement to a package of care financed from public sources. Because public budgets are usually set in advance, there is a trade-off between the price of care (associated principally with providers’ incomes) and its level and quality. The state—that is, the government—attempts to purchase the greatest quantity and quality available within the limitations of its budget. In other words, it tries to obtain the lowest prices for a given standard of care, whereas the medical profession tries to maintain high prices to cover providers’ incomes and protect what the profession may genuinely consider appropriate care and technology. This is a dilemma. The government must rely on expert opinion to determine the services and technology to be provided under public entitlement and in general. The experts must consider the population's well-being in order not to appear to be concerned solely with their incomes and with technology.

Consequently, the public or state solution usually is the following: First, the health budget is drawn up. Second, the level of reimbursement to providers is calculated. Third, the government and the experts’ representatives negotiate, reaching a compromise between their respective demands; this compromise also determines the types and levels of treatment and possibly the quality of care to be delivered. This process, which is typical of most publicly supported systems, usually is a mandatory formal negotiation between government ministries and “peak associations,” or designated groups of physicians (Richardson 1993;Stone 1980). This process reflects (1) the conceptual and practical complexity of defining perceived needs, as opposed to settling on a budget, and (2) the political economy, which links government to expert opinion. It does not take the consumers into account. The best example of this solution can be found in the former socialist nations, where consumers’ opinions are completely disregarded (Chernichovsky, Gur, and Potapchik 1996).

At one end, the solution based on market principles provides the widest spectrum of provider choice to those consumers who have good access to treatment, satisfying both them and their providers. This solution also presumably contributes to the efficient production of care. It does not, however, contribute to equity and macroeconomic efficiency, or the control of aggregate expenditures for medical care. In contrast, at the other end, the solution based on a centralized public system does not contribute to either consumer satisfaction or the allegedly efficient provision of care, but it does contribute to equity and the control of expenditures. Most solutions fall between these two. Neither the extreme solutions nor the intermediate ones, however, provide an institutional framework reflecting members’ interests as they perceive them as a well-informed and empowered group. The reform efforts that conform to the emerging paradigm in health systems do, however, offer an opportunity to rectify this situation.

The Emerging Paradigm and Its Enabling Features

The emerging paradigm has given rise to competitive budget-holding institutions that organize and manage the consumption of care that is a public entitlement in a regulated market. The best examples of this paradigm are the health systems of Israel, the Netherlands, Russia, and Colombia. To the extent that they hold the budgets and organize and manage the care for their members, American HMOs, German sickness funds, and British primary care trusts belong to the emerging paradigm (Chernichovsky 1995a). If Australian private corporations that employ and organize primary care physicians would be funded for their members’ public entitlement by capitation rather than fee for services, as is common today, they also will become OMCCs that conform to the emerging paradigm. Indeed, OMCC institutions have emerged in diverse systems, from traditional insurers (e.g., in Germany and the Netherlands), to labor union-cum-social security institutions (e.g., in Israel and Colombia) and state-run institutions (e.g., in Russia).

In addition to determining government policy, regulation, and research and training, the emerging paradigm identifies, at least conceptually, three systemic functions: (1) the financing of care, (2) the organization and management of care consumption (OMCC), and (3) the provision of care. The first function, the financing of care, is founded on principles of public finance, mainly means-tested mandatory contributions, though this does not necessarily mean that funds come only from general government revenues. Likewise, the third function, the provision of care, is based on decentralized management and elements of competition, but not necessarily the privatization or commercialization of care.

The second function, the OMCC, is probably the most definitive element of the emerging paradigm. Depending on the demographic, epidemiologic, geographic, administrative, and even cultural circumstances, this function can be institutionally based on centralized public administration principles (e.g., the health district in the United Kingdom); decentralized, market-oriented and competitive principles (e.g., sickness funds in the Netherlands); or a combination of these (e.g., sickness funds and government in Israel). Consequently, public administrations, nongovernmental organizations, nonprofit institutions, and, possibly, for-profit institutions can, in principle, carry out this function. The trend, however, has been to create nongovernmental entities that can substitute for public administration.

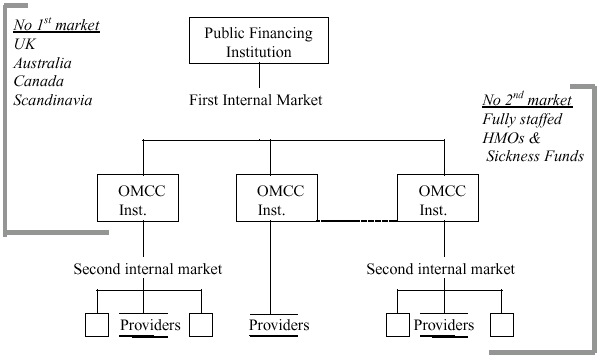

The emergence of three different health system functions governed by distinct market rather than public administration principles creates two internal markets (see figure 1. In the first internal market, competing OMCC institutions offer different packages of care and service options that are financed according to public finance principles. The public, or citizens, is the “buyer” in this market, in the following way: Citizens finance the care according to public finance principles. The specific allocation of these funds is based on the consumers’ endorsement of the OMCC institutions of their choice. In the second internal market, OMCC institutions procure care from providers, who are the sellers in this market. Two of the three functions may be combined, thereby eliminating one of the markets. Financing and OMCC are combined when in addition to financing, a state administration also organizes and manages the consumption of care. The OMCC function in this case may be rather ineffective. In this case, as shown on the left side of figure 1, the first market does not exist. OMCC and provision are combined when an OMCC institution is also a provider of care. In this case, as shown on the right side of figure 1 (referring to fully staffed or integrated HMOs and sickness funds), the second market does not exist. The extreme cases, when either the state or a self-financed OMCC performs all functions, are not considered, since they are becoming less common, giving rise to the emerging paradigm.

FIG. 1.

Schematic structure of the emerging paradigm.

Identifying these three functions and permitting their institutional separation are critical to the creation of a politically balanced system capable of representing its different constituencies: paying citizens, health care consumers, and providers. The importance of this identification can be seen in the British system and in the proposed Clinton health care program. Community Care Trusts or fund holders in the United Kingdom are both budget-holding OMCC institutions and providers. As such, they cannot adequately represent either side and, for that matter, function effectively, as they are charged with serving the diverse interests of the public or government (which pays them), consumers or patients, and themselves. New Zealand has had a similar problem with its reform efforts (Malcolm 1997).

The Clinton program, too, failed to separate the three functions and institutions that govern the health system according to the emerging paradigm. The proposed alliance of Clinton's program would not be a clearly accountable public regional administration that pools all funding but, in the first internal market, lets the people choose freely among competing OMCCs like health maintenance organizations (HMOs), which in turn let members choose among providers along the lines of the Dutch or Israeli models. Neither was the alliance meant to be a public administration with combined financing and OMCC functions; that is, it had no first market letting citizens choose freely among providers competing for publicly financed clients, along the lines of the British and Canadian models. Efforts to combine geographic and employment divisions confused matters even more.

When well defined and recognized institutionally, these three functions and the markets associated with them can represent (1) the government or paying citizens through the financing-cum-regulation functions, (2) consumers and patients through the OMCC function, and (3) providers through the provision function. In developed communities, where communicable diseases are not a major public health problem and which have resources for management and competition, an OMCC function institutionally separated from the other functions can empower consumers in the same national or regional system, through alternative consumer-defined models of public entitlement and the form of its provision. This empowerment can offer consumers the constitutional and institutional means to counterbalance the power of the government, on the one hand, and that of the providers, on the other. Accordingly, public entitlement can become more pluralistic and varied than when it is managed by a unitary public administration and also less individualistic than when it is managed mainly by providers who can manipulate uninformed clients even under the auspices of public financing and contracts. The challenge, therefore, is to create an appropriate constitutional and regulatory environment.

The Public Contracting of Care and the Empowerment of Consumers

Once funds to finance publicly supported entitlement are raised, the state can pursue one or more of the following strategies, which are not independent of the form of financing, to procure care:

Provide care directly through state-owned and -run facilities. This was common in the former socialist states and is to some extent the practice in Scandinavia.

Contract with freestanding providers directly, as do the Commonwealth systems of the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, for example. This option also includes a “public reimbursement system” in which consumers pay for care under public entitlement and are subsequently reimbursed by the state, as is optional in Australia and France.

Contract with providers indirectly, through OMCC institutions. This is common in the United States (under publicly supported programs) through HMOs and the like, and in several continental western European nations, Russia, and Israel through sickness funds. Although mandatory payments are sometimes made directly to sickness funds, contracting under compulsory insurance, as in Germany, for example, is considered part of this category.

Support health care consumers through “vouchers” that they can use to contract directly with providers. Under this scheme, which is not common, the citizen or household, usually in conjunction with an employer, makes tax-exempt contributions to a mandatory individualized account (medical savings account). Individuals can then use the money in these accounts to buy specified medical care directly from providers. Voucher systems of this kind are used in Singapore (Hsiao 1995;Massaro and Wong 1995) and have been introduced in China (Yip and Hsiao 1997).

These contracting strategies are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as several can exist within the same health system. The government may decide, for example, to provide preventive care directly, but contract indirectly for curative care. In general, the first strategy may be better than the others (1) at handling communicable diseases that entail adverse externalities, (2) in sparsely populated areas, and (3) with regard to expensive technology in which natural monopolies in the provision of care may arise. In those cases, the other strategies may be inefficient. With the relative eradication of those diseases and because it is the least sensitive to individuals’ preferences, this first strategy—common in the formerly socialist states—is increasingly becoming unpopular in socially and economically developed nations. The emerging paradigm shows that this type of provision is on the wane as governments move away from providing care directly.

Of the three remaining options, the “voucher,” or “medical savings account,” approach is conceptually most relevant to this discussion, which emphasizes vouchers as a particular form of contracting with providers rather than merely as a means of financing. Through tax exemptions (and, possibly, income transfers to those living in poverty), the voucher system is able to pool risks and support equity and thus is better than private financing. But it does not resolve equity problems. Individuals at similar income levels may have very different medical care needs, so it is difficult to adjust in advance individual voucher values to account for this variation in expected spending. As individuals with identical vouchers but different private means and need can choose their health plan or provider, the market can become segmented by risk. Accordingly, systems that use vouchers, such as those in Singapore and China, must provide for higher-risk (sicker) persons, using, for example, supply-side cost-control subsidies to providers and additional “catastrophic” insurance.

Vouchers may induce consumers to save. But—critically from the perspective of this discussion—they help preserve the supplier's monopoly vis-à-vis the individual patients who contract directly with providers, as in the private market. Consequently, from the perspective of this discussion, the voucher scheme or medical savings accounts scheme amounts to a combination of private market and direct contracting by the state, with citizens paying directly. The state subsidizes purchases of medical care through a tax exemption but delegates the purchasing right to the individual consumer, who deals directly with the provider.

Thus far, the two intermediate strategies seem to offer the most viable contracting of public entitlement: direct contracting, which may include a voucher scheme (for the subsidized part) by the state and also indirect contracting through intermediaries (OMCC institutions). These strategies have fared best in the most developed health systems supported by public financing principles. The trend of reform proceeds from “direct” to “indirect,” however. In the United Kingdom, reform has moved further from state-run direct contracting (Secretary of State for Health 1998), despite the debate (Ham 1998;Klein and Maynard 1998) over how much power the state is really relinquishing. In the absence of recognition (so far) in Britain of a distinct OMCC institution that is not a provider, this is a “quantitative” move: the government contracts with a relatively few primary care trusts rather than with many general practitioners. The government of New Zealand tried this approach (Upton 1991), and in Australia, there is a trend for large corporations to form and supply primary care to the public while charging the state (Scotton 1999).

Next we compare some fundamental characteristics of these two strategies from the perspective of consumer choice and empowerment. Consumers in countries with direct contracting systems (e.g., Australia, Canada, and those with voucher schemes) usually have—at least in theory—a wide choice of mainly primary care providers. However, they may not have a wide choice of care options, in either content or form. In response to the complexity of medical care and the alleged ignorance of the consumer (and also often that of the legislator and regulator), governments tend to define care under public entitlement conservatively. Even with numerous providers, direct purchasing is usually monolithic. That is, in most systems the standard of care, including oversight of safety and quality, is defined by medical professionals who have a vested interest in the “established” system, as argued earlier about “peak associations.” “Alternative medicine,” for example, may not be authorized even if it is harmless, legal, endorsed by a minority of practitioners, and considered legitimate by much of the population. Furthermore, this issue pertains not only to the type of intervention but also to the provider.

In addition, the state or the paying public does not have much control over the interaction between patient and physician. Even if the state controls prices, for example, it cannot effectively control the volume and quality of care or readily lift typical constraints on the solo primary caregiver, because of insufficient peer review and outdated technology of care, broadly defined. Unable to exploit economies of scale, the solo general practitioner may be unable to use advanced technology in the community but, to preserve quality care, must refer patients to secondary and tertiary providers.

Indirect contracting through intermediaries or OMCCs can overcome the disadvantages of direct contracting. Unlike an individual patient, groups organized as OMCCs can wield knowledge and judgment, counterbalancing that of the medical profession, and thus they are better than the state at overseeing the quality of care. An OMCC can also use technology more efficiently, as discussed below.

In addition, indirect contracting can help patients choose the content and form of care. If OMCCs can form easily and are numerous, then individuals also can form groups and contract with the OMCCs according to their particular preferences. Consumers can help determine the nature of these institutions if the institutions are not allowed to reject applicants for their public entitlement. Organized clients—rather than payers—can introduce pluralism into a publicly financed health system. The authority delegated to these institutions or consumer groups means that they can substantially determine both the elements and form of the delivery of public entitlements. Once in place, the OMCC assumes a basic fiduciary function supported by both state regulation and member representation.

At this juncture, we turn to three seemingly unrelated concepts: “transparency,” “accountability,” and “managed care.” The transparency between individual “contributions” and “entitlement” to goods and services is greatest in privately financed transactions. This transparency, as well as the accountability of suppliers to contributors, diminishes when public financing principles are invoked, thereby severing the direct link between contribution and entitlement that exists in a privately financed transaction. Some of this transparency is maintained in instances of the compulsory group insurance model (GIM) (e.g., Germany) and the (true) social insurance model (SIM) (e.g., Israel, the Netherlands) (Chernichovsky, Bolotin, and de-Leeuw 2001). In these two models, taxes and other obligatory contributions for care are earmarked. In the GIM, however, contributions are made by groups of insured—usually based on workplace—directly to the sickness funds or providers of their choice. In the SIM, contributions are pooled in a public trust—national, regional, or both—that uses a universal mechanism to allocate financing to sickness funds and providers. The SIM, unlike the GIM, thus has no direct link between contributors and beneficiaries. Consequently, under the GIM, with its compulsory insurance, the group has considerable control over the nature of the entitlement because of the direct association between contributions and sickness funds–cum-providers (Chernichovsky and Potapchik 1998). This transparency is almost lost, however, under the SIM, in which contributions are still earmarked, but to a common pool. And transparency disappears completely when public entitlement is financed through general revenues that are not so designated.

OMCC institutions such as sickness funds and member-based HMOs can be used to return both choice and control over entitlement to the group in a way that is consumption based rather than, as in the GIM, contribution based. This is possible under the SIM and the general tax–financed models. In those models, because all funding is pooled and then redistributed according to a universal criterion, regardless of the source of the contribution, the group can form around a pattern of care consumption (e.g., the Netherlands, Israel, Russia) rather than around the contributing workplace (e.g., Germany).

Consumption-based grouping and contracting are best served by nonprofit OMCCs, for then accountability is to members rather than to a small group of shareholders. Depending on the regulatory system, shareholders of the OMCC may be seen as members who hold nontransferable stock. This option needs to be carefully regulated, to minimize “cream skimming” by the group.

Managed care institutions in the United States are still accountable to the payers, even in government-financed public programs. In other words, the beneficiaries are not regarded as “payers,” even when the financing is tax based, let alone when employers finance care. This follows the basic philosophy of the American system that medical care is not a right, that health insurance purchasing cooperatives are ultimately accountable to payers, notably employers and the government, rather than to their members (Rodwin 1996;Zelman 1993). This philosophy is reflected in Schlesinger's approach, in which he regards “plans” as agents for the paying government, whereas providers are the agents for their clients (Schlesinger 1997). Clients are not regarded as potential agents for themselves. As envisioned here, OMCCs are also care managers, but they are first and foremost consumer associations with the right to determine the scope and form of care consumption under public entitlement.

This institutional scope for diversity, as well as for consumer choice and empowerment, is not without cost. OMCCs add an administrative layer absent from the state-administered Commonwealth and Scandinavian systems, which probably raise the cost of running the system, even when considering the potential savings from reducing the government's involvement. In Russia and Colombia, such institutions, not emerging from traditional insurers, constitute a net addition to the system, in the same way that various kinds of trusts do in Britain. The justification for this cost ultimately rests on how well OMCC institutions can provide for consumer-oriented diversity and can control the quality and cost of care in the fiduciary roles they may assume for their members, subject to limits that society or the paying citizens can rightfully impose through the government.

Group Empowerment through Capitation

Entitlement to financial means that citizens can use at their own discretion provides more choice than does the common form of public entitlement, a predetermined set of goods and services. An extreme case would be a fully subsidized voucher granted to the individual. For reasons discussed earlier, a voucher to an individual is problematic; apart from the financing and risk-pooling issues, a fully subsidized individual voucher amounts to direct contracting by the state but management—also for provider reimbursement—by the individual. In contrast, vouchers granted to a group—universal capitation payments to OMCC institutions—overcome the problems of the individual vouchers while preserving their advantages at the group level. The group can share risks among its members while still using the funding at the group's discretion, by purchasing public entitlement according the group's choice.

A system that makes capitation payments to OMCC institutions combines the advantages of a centralized, state-run system with those of a decentralized, market-based system, reflecting the fundamental philosophy of the emerging paradigm and its enabling organizational and institutional features. As in the state system, the levels of public expenditure on medical care are determined in advance. In addition, the capitation formula can be designed so that public resources are allocated according to a set policy and priorities. At the same time, capitation lets consumers choose among competing OMCC institutions offering an assortment of services, subject to some mandatory and other regulations.

Capitation has long been recognized as a financial mechanism that allocates resources and pays providers in systems with widely differing structures and philosophies (van de Ven, Ellis, and Ellis 2000). It is used to determine the allocation of the bulk of public funding in the emerging paradigm systems mentioned earlier in Colombia, Israel, the Netherlands, and Russia. The British National Health Service uses capitation for the regional allocation of resources and for community health care (U.K. Department of Health and Social Security 1988). The U.S. federal and state health administrations use capitation to pay providers for care, received through HMOs, for beneficiaries of publicly funded programs such as Medicare and Medicaid (Hadley and Langwell 1989).

Within the pluralistic emerging paradigm suggested here, capitation has another important feature: it specifies in financial terms the public entitlement to a package of care whose substance and form are largely determined by consumers as a group. Since the groups in the emerging paradigm suggested here might chose different care patterns, some might argue that a group should be granted a capitation sufficient to cover its chosen care and provision arrangements. Such a group-based capitation would come closer to a fee-for-service scheme, however, and would therefore induce the group to choose an expensive package. This in turn would undermine one of the basic objectives of capitation in a publicly financed system: containing costs and promoting efficiency. The remaining challenge is to permit a group's choice of specific entitlement under a publicly supported capitation system.

The system proposed here is intended to provide equal opportunities for choice rather than equal services. Namely, the capitation payment should be universal: all groups should receive (in financial terms) identical, “standardized” entitlements. “Standardized” here refers to the need to adjust payments according to age and gender only, with additional adjustments for regional variations in medical infrastructure that may affect equal opportunities for access to care. In this way, the system can meet a formidable challenge on the issue of equity. Universal entitlement nowadays conforms to the fairness principle: what cannot be given to all is given to none. The capitation scheme, envisioned as a “group voucher,” would be more equitable in that it enables the group match between public resources and individual need. The proposed capitation scheme should benefit from an environment that enables sharing risk with providers and offers a safety net for extreme and unforeseen circumstances.

Group Choice

According to the principles of public finance and entitlement, the choice of the group organized as an OMCC institution has limits. Society may not permit such choices with regard to those aspects of care that involve externalities affecting the well-being of other people. Cultural, ethical, and legal issues concerning what society may accept and sanction are pertinent as well.

Communicable and mental diseases or public health in general may not be left entirely to the OMCC's discretion because of the adverse externalities that these diseases may generate. However, since OMCCs are community and client based, they are likely to be more inclined and better positioned to deal with these situations than individuals and their physicians are when “managing” care under direct contracting. Prospectively budgeted by capitation, self-serving OMCCs have an incentive to invest in preventive care in association with curative care. In addition, the greater the geographical concentration of an OMCC's membership is, the greater the incentive to deal with adverse externalities will be.

In areas where communicable diseases are the major public health concern, the emerging paradigm may not apply at the outset, as the scope for competing OMCCs and providers may be limited and the OMCC function may best be handled by a local (noncompetitive) public administration. Similarly, emergency services would be beyond individual or group discretion, given that society may be unwilling to tolerate the selective treatment of accident or disaster victims. Such care may be left to public administrations. This argument goes beyond the economies-of-scale and efficiency argument associated with large-scale emergency services and relief operations, as it also concerns moral and ethical issues regarding accident and disaster victims.

Society may allow OMCC institutions a degree of free choice in certain broad, gray areas. Euthanasia, which is clearly linked to intense ethical and legal debate, is the most extreme example. Society may or may not deny the OMCC institution this option. In general, we can assume that a group could choose this option if it were legal.

Group choice has yet another dimension: choice of membership. Social limits are needed here, too. In addition to operating within the financial framework of capitation, so that the group is not formed around expensive conditions, the group should have no right to refuse membership or expel members, so that the group is not formed around relatively inexpensive health conditions. Capitation, on the one hand, and mandatory acceptance of members, on the other, set boundaries broad enough to forestall monolithic solutions to both type of care and membership and forms of delivery.

Allowing consumers to choose among competing diverse care options for their public entitlement can reduce their need to seek privately financed care, since some consumers’ needs would now be met by their choice of group for public entitlement. Still, the group, as well as individuals, may want to supplement their public capitation allowance with private funding to broaden individual choice. Therefore, a democratic society must permit the private procurement of care, either directly or indirectly through insurance. As Chernichovsky (2000) showed, the challenge is to regulate the system so that the private funding does not interfere with the objectives of the public system (i.e., equity and aggregate cost control) and providers do not use this funding to promote private spending. To this end, it is best to segregate the publicly and privately financed systems completely, as is done in Canada. A second best alternative, made possible under the emerging paradigm, is to permit OMCCs to offer supplementary insurance but to disallow providers that work under publicly financed contracts also to offer private services under extra billing arrangements, as is done in Australia.

According to the general approach described here, society sets the boundaries beyond which it may deny an individual or a group the right to refuse treatment in the group. Beyond these boundaries, set by state regulation, individuals can enroll—for their public entitlement—in a competing OMCC institution that offers their preferences for care. This institution—but not the sole individual or the state—has the right to define publicly supported entitlement within the society's limits. It can establish appropriate information, decision-making, and control mechanisms and, more important, can legitimize the people's choice by being democratic.

The potential impact on OMCCs of consumers’ quid pro quo under public entitlement also demands attention, since members are periodically free to change their OMCC institution. A consumer usually chooses an institution—namely, a specified package of care, as well as its form or pattern of consumption—when healthy. But when people become ill, their medical needs and the entitlement they desire may change. Organizing the system to prevent ill patients from changing OMCCs might warn people against making a hasty choice of OMCC institution when healthy. Further, this would reduce the incentive to form esoteric groupings. At the same time, blocking the option to change OMCCs when ill may create serious moral and ethical problems; society may not wish to “punish” a patient after the fact for a “wrong” decision made when healthy. Therefore, the option for changing one's OMCC affiliation when sick should not be ruled out. Still, OMCCs may focus on or specialize in the organization and management of particular kinds of care that they can sell or subcontract to other OMCCs. That is, a market mechanism could help substitute for changing one's enrollment when sick.

Organizing and Managing the Consumption of Care

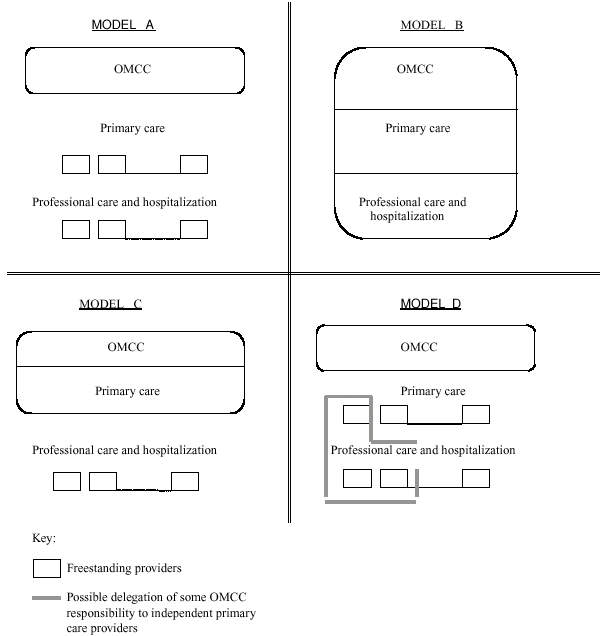

The extent to which consumers should be allowed to determine the nature of their public entitlement is controversial, although there is little dispute that the group, using a publicly financed capitation, may direct the OMCC's organization and operation. The group or OMCC institution in fact internalizes any benefits or costs of such decisions. Still, the paying public may promote particular types of organizational structures that conform to public policy objectives. OMCC institutions may follow one or a combination of four economic-administrative models, which differ in how they organize services and the degree of members’ choices permitted under the group's specific public entitlement. These characteristics, in turn, influence the institutions’ ability to achieve various health system objectives.

Under the first, market-oriented, model (A in figure 2), the OMCC institution procures primary, secondary, and tertiary services from freestanding providers in the second internal market making up the health system and determines its working arrangements with them. The customer then chooses a service provider from the list of contractors. The OMCC may let members choose a provider not on the list if they (or their potential insurers) are willing to make additional payments. To improve efficiency and member satisfaction, however, the OMCC institution may decide to own and operate certain services with salaried staff and to provide these services directly, in cooperation with the independent providers.

FIG. 2.

Organization and management of care consumption (OMCC) and care provision models.

This model gives members maximum choice over their providers, the degree of choice being almost equivalent to that enjoyed under free-market conditions but provided within a publicly financed OMCC framework. The model resembles the state's direct contracts with providers in Australia and Canada, but there the contracts are made according to members’ choice, whereas in this model the contracts are made and overseen by an OMCC institution.

The second model (B in figure 2) is the most similar to the fully integrated staff model. In this model, the OMCC institution operates its own facilities, usually with salaried employees, and provides all or most services directly. Such fully integrated institutions organize, manage, and supply services to their members, who are entitled to services primarily, if not exclusively, from those establishments.

Recall that a fundamental principle of the emerging paradigm is not only to encourage pluralism and member empowerment in publicly supported systems but also to promote the adoption of various approaches to the organization and delivery of publicly supported care. At least conceptually, these approaches lie between models A and B described in figure 2. Model A takes a competitive perspective that is akin to the market model, whereas model B is similar to a fully integrated public model. The advantage of the emerging paradigm is that these two extreme models and combinations thereof can coexist within the same publicly financed health system.

OMCC institutions following the third model (C in figure 2) fall between models A and B. They maintain a salaried staff to provide primary services but usually purchase other services, mainly hospitalization, from outside providers. In this model, primary care providers act as gatekeepers for referrals, regulate the quality of care, and control expenditures.

According to the fourth model (D in figure 2), an OMCC institution contracts with a community clinic, paying a capitated rate, to provide the entire service package or at least a large fraction of the OMCC's services. The clinic functions as a secondary budget holder, the OMCC institution being the primary holder, and is obligated to provide members with the specified services, particularly access to specialists and hospitalization. The OMCC institution thus transfers to the community clinic all or most of the responsibility for providing care through the public program, including financial accountability. Members are free to select a clinic but not necessarily the services and personnel they prefer in the clinic. This model entails a degree of duplication and redundancy. Two budget holders operate concurrently. The first is the OMCC institution (similar to Britain's District Health Authority operating as an OMCC). The second is the budget-holding community trust or provider. The two also have management roles and preferences that may conflict.

Table 1 shows the models in order of hypothesized success at achieving the basic goals or utilitarian attributes of the health system in a competitive environment. A low rating (e.g., 1) represents a smaller capacity to meet a particular objective than does a higher rating (e.g., 4). The thinking behind the rankings is based on assumptions—which are hard to substantiate empirically—about how to shape the behavior of service providers toward members and what power the OMCC (or government) has to do so (Chernichovsky, Bolotin, and de-Leeuw 2001).

TABLE 1.

Rank Ordering of Models by Their Hypothesized Systemic Goal-Achievement Capabilities

| Systemic Goal | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expenditure Control | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Member Satisfaction | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| (Freedom of Choice) | ||||

| Member Satisfaction | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| (Quality of Service Provision) | ||||

| Accessibility and Equity | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Quality of Care | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

Key:1 = worst, 4 = best.

Expenditure Control

Model C is hypothesized to be the best at controlling expenditures. In this model, the primary care practitioners act as gatekeepers, safeguarding costly secondary and tertiary services. In addition, contrary to model B, the OMCC need not always pay the full fixed costs of hospitalization. In model D, however, the budget holder does promote cost savings, especially for specialists’ services and hospitalization; therefore, model D would take second place, after C. In contrast, model A should have the greatest difficulty controlling expenditures, since its members have considerable freedom to choose service providers, who in turn have little reason to hold down costs, especially if they operate on a fee-for-service basis and especially when extra billing is permitted. Model B is also ranked relatively low, owing to the inevitable need to finance the full fixed cost of a system of hospitals even when they operate below capacity (Chernichovsky 1995b).

Member Satisfaction

Two factors influence member satisfaction: freedom of choice of providers and quality of service (in contrast to quality of care). Studies have shown that satisfaction is positively correlated with freedom of choice (Blendon, Leitman, Morrison, et al. 1990). Models A and D are hypothesized to be the leaders in member satisfaction because they permit greater choice of providers. Models A and D also dominate in service quality, since competing service providers, rather than OMCCs, have a vested interest in retaining their members. In contrast, providers operating under model C, and especially those operating under B, do not have this incentive. Model A is preferable to model D because model A has more choice of provider than D does.

Accessibility and Equity

Providers’ incentives for rejecting potential members are the best indicator of the model's success at achieving accessibility and equity. Accordingly, model A rates the highest here because of the service providers’ inherent interest in seeking patients, especially because fee-for-service is the main reimbursement method. Model B rates the lowest because the (salaried) provider has no incentive to seek patients; this also is true under model D. As a rule, the OMCC's desire and ability to stint on quality rise with the number of services it provides directly, as in model B.

Quality of Care

The ability to control quality of care and the desire to preserve it are related to two factors: the inclination and ability of providers to reduce costs to the point that quality is sacrificed, and the OMCC institution's ability to counterbalance that. Therefore, model C is preferable, owing to its ability to control the movement of patients and ensure continuity of care while saving on unnecessary care, mainly hospitalizations. Indeed, these potential benefits may be somewhat undermined in model B, which, because it owns hospitals, may tend to “overhospitalize” patients, since the marginal cost of hospitalization may be negligible. Model D rates the lowest because of the budget-holding clinics’ inherent inclination to cut costs for hospitalizations, coupled with the possibility that OMCCs may have little control over the clinics’ operations. The relevant incentives might change if community medicine is carried out within a clinical framework with several practitioners or a group practice, as opposed to a solo practice. Such a group could use technology more appropriately and have better peer review, even if informal, than solo practitioners could. However, the incentives to reduce expenditures might encourage the clinics receiving the capitated payments to withhold treatments. Although this might mean avoiding unnecessary hospitalization—or “surplus medicine” in general—there is a risk that the quality of care might diminish too. Nevertheless, when clinics have long-term contracts with patients, these arrangements might promote improvements in preventive medicine (Hadley and Langwell 1989).

It is not clear that the group with the freedom to organize will decide to choose model A, which is hypothesized to yield the highest member satisfaction. Some features of this model tend to increase costs. Informed individuals may prefer to give up features of model A that improve member satisfaction in favor of the potential savings achieved by other models, provided those savings can indeed be realized by the group and its members.

An OMCC is considered to have the right to determine its own organizational structure and method for administering services. Nonetheless, as discussed above and summarized in table 1, some features of how the organization is structured and the way care is consumed mold its capacity to fulfill health system objectives. Accordingly, it is impossible to deny the government the power to make policies to support, for example, aggregate cost control and production efficiency. It follows that the government can certainly promote, preferably by financial mechanisms, the adoption of organizational criteria that support its policy priorities. If, for example, the government is interested in efficiently controlling expenditures, it may promote OMCCs of model type C. If it is more interested in member satisfaction and equality, it may support OMCCs of model type A. In general, governments wanting to emphasize quality of care should promote systems based on community clinics where several physicians can work side by side, rather than systems with solo practitioners who work in isolation. This isolation can be aided by institutions of model type D. In any case, the emerging paradigm allows natural experimentation with alternative organizational models of OMCC and delivery care.

Group Size

The size of enrollment is important, since it determines the level of financial risk assumed by the institution and the efficiency of its operations. The more members a group has, the less such risk it will have under a capitation allowance. Consequently, the larger the group is, the less likely its policies and practices will adversely affect equity and quality of care. Adverse policies and practices include (1) membership selection or cream skimming—choosing only those members expected to incur lower costs so as to preserve a higher anticipated operational surplus; (2) risk selection—enrolling groups whose cost distribution is small relative to that of other groups, so as to reduce the financial risk assumed by the capitation recipients; and (3) treatment selection or quality skimping—choosing less costly (and possibly inferior) treatments, or stinting on service. Treatment selection, affecting quality of care, is most commonly found in providers that receive capitation but may apply also to OMCCs of model types B and C that provide services and to the other two types indirectly. Although these practices are usually considered in the context of for-profit organizations, they can also be found in not-for-profit OMCCs. In particular, small consumer groups may adopt the same selection criteria as a group of shareholders would.

In addition, subject to the limitations discussed later, large organizations can reduce costs by taking advantage of economies of scale stemming from a better use of infrastructure, including costly technology. Furthermore, providers in group practice are more subject to peer review than are solo practitioners, suggesting that larger groups can provide better care. Size thus can be beneficial.

On the negative side, however, a large membership may weaken competition and responsiveness to members’ needs: the larger the groups are, the fewer there will be to compete. Furthermore, even when large OMCCs are democratic, they may become excessively bureaucratic and thus not responsive to members and change, and they may develop monopsonistic powers over providers. Similarly, large providers—particularly regional hospitals—may develop monopolistic power over OMCCs. Hence, excessive size may well interfere with competition, pluralism, and freedom of choice: the fundamental principles of the emerging paradigm.

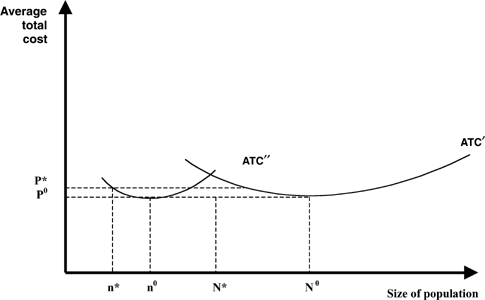

The situation with regard to efficiency and quality vis-à-vis competition and sensitivity to clients can be described with the aid of figure 3. Assume that there are two internal markets, one in which the state contracts with the OMCC institutions and the other in which those institutions contract with providers. In figure 3, ATC′ (Average Total Cost) reflects the long-term cost structure for a specific technology to be used by OMCCs. Another technology exists in the second market, whose cost structure is described by the curve ATC″. In the first market, from the national perspective, the optimal population size to achieve minimal expenditure on a unit of technology utilization is N°. In the interest of competition, if regulation permits OMCC institutions to be no larger than N* (< N°), capitation and other remittances will not cover the use of this technology at its minimum cost. The government then has two options. First, it can prohibit OMCCs from using the technology within the framework of their public contracts. In this scenario, the government itself would be required to finance the technology by supporting both investments and ongoing operations; it could do this through national or regional “excellence” centers accessible to all OMCCs. Alternatively, the government could allow OMCCs to use the technology, in which case it would pay at a level of P*, included in the capitated payment. It would pay P* knowing that the difference (P*− P°) is the “price of competition” in the system, provided that small operations do not infringe on the quality of care.

FIG. 3.

Cost of care, technology adoption, and competition.

The situation of the OMCCs vis-à-vis service providers is analogous to that of the state vis-à-vis the OMCCs. In the interest of maintaining the competition among providers (and preserving the OMCC's own monopsonistic power), OMCCs may bar the provider from treating a population beyond size n* (per curve ATC″), even though the provider could treat a population of size n° more efficiently. Here, it is the OMCCs that must decide whether to supply the technology separately in their own centers or through competitive providers, although the latter option would be more costly.

This discussion reveals the inherent conflict in any health system adopting the emerging paradigm in which the government or public interacts with the OMCCs which in turn interact with the providers. In order to resolve this conflict, a clear state policy is required for technology and the size of OMCCs. In any case, if promoting competition in peripheral areas is important, small OMCC institutions should be supported even if they are relatively costly.

Additional Roles of the State

The government has a basic mandate to formulate national health policy and regulate the medical care system. It must also support education and research, as they cannot depend entirely on private financing. Next I focus on those functions of the government, as an agent of its paying citizens, in support of the fiduciary role of the OMCC institutions representing consumers. In addition to (1) defining the scope of group choice,(2) possibly swaying the nature of the OMCC's operations, and (3) setting the limits on group size, these functions are as follows:

Formulation and Protection of the Budget for Public Entitlement

A government has two responsibilities for funding its country's health system: direct financial responsibility for funding the public entitlement, in full or in part, and protection of public resources from financial and other risks. Whenever the public entitlement is financed exclusively through the state budget, the government's direct responsibility is clearly defined in accordance with its general budgetary responsibilities. Disparities may emerge, however, in other configurations. In western Europe, only a portion of public entitlement is funded through the general budget; another large part is from compulsory, earmarked contributions by employers and households and thus depends more on the business cycle than does the government budget, which can be countercyclical. But besides wanting to keep health spending in check, the government should want to keep it stable and so must protect the health budget from the business cycle (Chernichovsky and Potapchik 1998).

To protect public resources from financial risk, the government must protect its funds from speculative use by OMCC institutions. That is, it must both regulate the OMCCs and help them fulfill their fiduciary role with regard to finance. This may require not only overseeing their financial management so that they do not expose financial reserves to undue speculation but also ensuring that the OMCCs have access to low-risk financial instruments like government bonds.

The Capitation Formula and Policy Implementation

After the overall health budget is resolved through the political process—reflecting “felt need” and fiscal policy—the capitation formula must be determined. This formula, as mentioned earlier, specifies the level of public entitlement in financial terms, which are standardized per capita. This is the package of care, the equivalent of a voucher, but for the group, transferred to OMCC institutions. The capitation formula can be designed to promote particular health policy goals by providing larger payments in some contexts, especially in underserved populations or remote areas. In other cases, the formula may provide smaller payments to discourage activities such as the excessive use of particular costly technologies. Regardless, the government needs to update periodically the age- and gender-based risk adjusters used in the capitation formula in line with the nation's cost experience and preferred policies, to induce OMCCs to follow a desired policy.

The Reduction of Risk Selection and Quality Skimping

Reducing risk selection and quality skimping are of prime concern, especially in a capitation or risk-based pay system (van de Ven, Ellis, and Ellis 2000). The temptation to skimp on quality may be reduced in the member-controlled OMCC institutions proposed here. However, the potential for risk selection by the OMCC institutions is not eliminated because the institutions are run by the members; the capitation formula is “right” (to the extent possible); and the institution is of the right size. To minimize the problem even more, the government must require that the OMCC accept everyone who wants to enroll.

Competing OMCC institutions and providers determine the nature of the second internal market, in which the state should, in principle, be minimally involved. However, to support the system's operation through this market, especially with regard to OMCC models B, C, and D, the government should help establish—primarily by gathering and processing information—risk-sharing mechanisms between OMCCs and providers. In primary care, having a “capped” fee for services, as in the German system, or a disease classification grouping (DCG) could be useful. In secondary care, using a diagnostic related grouping (DRG) system would be helpful.

Another way of reducing the incentive and scope for risk selection is through “carve-outs.” The state may pay for particular medical conditions or treatments, or cover certain groups separately, outside the extent of the capitation payment. For example, the state may carve out treatment for those with extremely severe and expensive conditions such as HIV/AIDS; those with slowly developing diseases such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis; patients who need diagnosis and treatment using new and expensive or experimental technology; and social groups that require special attention, such as indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities (Chernichovsky and Kunitz 2001).

The Regulation of Monopolies and Monopsonies

It sometimes is impossible to prevent the emergence of “natural” monopolies and monopsonies. They may arise in the case of technologies with large fixed costs in sparsely populated areas or where communicable diseases are the principal public health problem. The government should try to prevent the exploitation of monopolistic powers by requiring monopolistic service providers to accept every patient at a price it sets.

In some cases, OMCC institutions have significant control over the market for health care providers. We should stress that regulating such monopsonies is a conceptually complex issue in the emerging paradigm. In this paradigm, OMCCs have been given the right to manage care, to counterbalance the monopoly power of providers over individual clients. “Excessive” monopsony power may exist as well, and a delicate balance is needed to control it. While consumer pressure to provide high-quality service and care is assumed to mitigate the inclination to exploit providers, more may be required. One way that the government can address this issue is to set the fees that OMCCs pay for services, without requiring them to purchase those services from a particular provider (as in the Netherlands). Two other ways would be to increase the number of OMCCs by limiting the size, assuming the consequences of small size, and enhancing competition among them. Moreover, at the extreme, when no competition between OMCCs is feasible, their function can be executed by a local administration.

Health Education and the Provision of Information

Information improves overall oversight and quality control. In addition, the more information that consumers have, the more opportunities for competition and the realization of its benefits there will be. The state's interest in controlling the expenditures and efficiency of the health system requires it to collect data and disseminate information. One such obligation is to inform OMCCs, providers, and consumers about which medical treatments and services have the highest quality, most efficiency, and greatest member satisfaction. In general, while the government must have enough information to promote competition, it needs the same data to draw up the budget, manage the system, set the capitation formula, monitor payment systems, and oversee quality generally. The OMCCs’ role as the processors of information is essential to their role in empowering consumers to manage their medical care under public entitlement.

Technology, Investment Policy, and Size of Operations

Capitation and the payment mechanisms associated with it can compensate for the capital costs incurred by both OMCCs and service providers. In this case, payments support appropriate investments, although problems arise for expensive technologies with large fixed costs, which make economies of scale particularly important. The government vis-à-vis the OMCCs and the OMCCs vis-à-vis the providers will have difficulty choosing an investment policy to be implemented in the interests of efficiency and the members’ freedom to choose. As I emphasized concerning the size of the OMCC (and the provider), the government should have the authority to regulate the acquisition and use of technology. Moreover, given the current pace of technological development, a responsive policy and constant regulatory adjustments are paramount to ensuring its efficient use.

In sum, the government should avoid as much as possible issuing directives to protect the paying public's interest. Rather, it should achieve that objective through the capitation system, information, guidelines, and the support of contractual arrangements between members and OMCCs—and between the latter and the providers.

Summary: The Social Contract

Through the government, the state bears the final responsibility for securing the publicly supported care benefits, and so it is important to identify clearly the rights of the government representing its paying citizens, of the OMCC institutions representing their members and patients, and of the providers.

From a political-institutional standpoint, the emerging paradigm's structure, which is governed by OMCC institutions as advanced here, can be conceptualized and implemented as a corporate federation of territorially based OMCCs and the Ministry of Health. Such a system would confer some of the fundamental qualities of a federation: the right to be represented in decision-making institutions and especially the right of the federation's members—in this case, the OMCCs—to make the final decisions on specific issues. A regional system, as part of the state federation, as in Germany, Australia, and Canada and as introduced in Russia (Chernichovsky and Potapchik 1999) would be consistent with the principles stipulated here. That is, OMCCs would represent their members in any territorial state (if the state itself has a federal structure), with the (regional) Ministry of Health operating as the head of the “federation.”

Consistent with its traditional role, the state's tasks would include drafting a convention as the cornerstone of the health system's organization and management. This convention would establish how the public entitlement is defined and also describe the governing structure that is to deliver the publicly funded care. The following are some of the principles on which such a convention should be based:

Principle 1: The system's management must not deviate from the nation's laws, including those regarding taxation and budgeting. This principle subordinates the health system, even when it is financed by designated contributions, to state laws and overall social and economic policy.

Principle 2: The state has the ultimate responsibility for overseeing the proper financing and organization of a health system that asserts its citizens’ right to a package of care, socially and individually defined. The state carries out this responsibility by means of public finance principles—taxes, and other mandatory means-tested contributions—and through the OMCC institutions.

Principle 3: Through the OMCC institutions, individuals have the right to choose among a range of services they want to receive through the publicly supported funding and options about how those services will be provided. The choices should be limited to the extent that they create any negative externalities or disrupt the efficient operation of the system.

Principle 4: The OMCC institutions are to act as representative bodies within the health system. These institutions should, therefore, be governed by elected, rather than appointed, institutions. This principle points to the importance of having nonprofit OMCC institutions.

Principle 5: To secure pluralism, choice, and systemic efficiency, the OMCC institutions cannot be above or below a legally stipulated size. Small OMCCs can also facilitate the democratic process.

Principle 6: The OMCC institutions are to be considered part of a “corporate federation”; together with the Ministry of Health, they comprise the health system, on a national and/or regional level. OMCC institutions are to sit as members on a national health council, on which small OMCCs should be overrepresented. The council's task is to determine health system policy, with a special focus on formulating budgetary proposals to be transmitted through the Ministry of Health to the government responsible for the orderly management of the system.

Principle 7: The OMCC institutions are entitled to make the final decisions on certain subjects pertaining to their operation under the capitation system. This right concerns chiefly the way that OMCCs specify the care to be provided and how they organize and manage it. Furthermore, the government cannot abrogate these rights through regulation.

Principle 8: The government, as represented by the Ministry of Health, has the right to make the final decisions on a range of issues, subject to the OMCCs’ constitutional rights as just described. The government can make decisions about those elements of care that are not the prerogative of the OMCC institutions. In particular, the government should determine the size of the OMCCs, the capitation formula, the public-private mix in the financing and provision of care, and the policy regarding the use of “expensive” technology.

Principle 9: In those cases in which the OMCC institutions have the right to choose, the government may use incentives, through capitation, that encourage behaviors consistent with the nation's health policy goals.

These principles set the framework for a health system that builds on the emerging paradigm but defines the constitutional roles of the government, on behalf of paying citizens, and of the population as consumers who are members of the OMCC institutions.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the Centre for Health Program Evaluation, Australia, for providing technical support while writing this paper, and anonymous reviewers for most insightful comments.

References

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon EJ, Leitman R, Morrison I, Donelan K. Satisfaction with Health Care Systems in Ten Nations. Health Affairs. 1990;9(3):92–185. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D. Health System Reform in Industrialized Democracies: An Emerging Paradigm. Milbank Quarterly. 1995a;4(3):127–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D. The Political Economy: Introducing a New Technology for Secondary Prevention When Hospitalization Cost Is Discounted. International Journal of Health Sciences. 1995b;6(3):133–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D. Private Finance, Supplementary Insurance, and Reform in the Israel's Healthcare System: Perils and Prospects. Social Security. 1998;5:29–48. special ed. [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D. Boston: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2000. The Public-Private Mix in the Modern Health Care System—Concepts, Issues, and Policy Options Revisited. Working paper W7881. [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D, Barnum H, Potapchik E. Health System Reform in Russia: The Finance and Organization Perspectives. Economies of Transition. 1996;4(1):113–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D, Bolotin A, de-Leeuw D. Boston: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2001. A Fuzzy Logic Approach toward Solving the Analytic Maze of Health System Financing Working paper W8470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D, Chinitz D. The Political Economy of Health System Reform in Israel. Health Economics. 1995;4:127–41. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730040205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D, Gur O, Potapchik E. Health Sector Reform in Russia: The Heritage and Private-Public Mix. MOCT. 1996;6:125–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D, Kunitz S. “Medical Minorities”—Towards a New Dynamic Approach to Study Equity and Efficiency in the Health System.

- Chernichovsky D, Potapchik E. Sigtuna, Sweden: An Optimal Healthcare Financing Regime in Systems Based on Mandatory Earmarked Contributions and General Revenues: The Case of Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Chernichovsky D, Potapchik E. Genuine Federalism in the Russian Health System: Changing Roles of Government in the Russian Health Care System. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law. 1999;24(1):115, 44. doi: 10.1215/03616878-24-1-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley JP, Langwell K. Managed Care in the United States: Promises, Evidence to Date and Future Directions. Health Policy. 1989;19:91–118. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(91)90001-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham C. Elements of Decentralization in Plans to Reform NHS May Prevail. British Medical Journal. 1998;317:753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao W. Medical Savings Accounts: Lessons from Singapore. Health Affairs. 1995;14(2):260–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Health Economics (IHE) The Swedish Institute for Health Economics: Equal Opportunities and Free Choices in Health Care. IHE Information. Lund. 1996;3:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Klein R, Maynard A. On the Way to Calvary. British Medical Journal. 1998;317:5. [Google Scholar]

- Londoño JL. Comparative Health Reforms: Asia and Latin America. INDES: International Development Bank; 2000. Managing Competition in the Tropics. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm L. Gp Budget Holding in New Zealand: Lessons for Britain and Elsewhere? British Medical Journal. 1997;314:1890. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7098.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro TA, Wong YN. Positive Experience with Medical Savings Accounts in Singapore. Health Affairs. 1995;14(2):266–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Health Care Systems in Transition: The Search for Efficiency. Paris: OECD; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JJ. Pressure Groups. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwin AM. Consumer Protection and Managed Care: The Need for Organized Consumers. Health Affairs. 1996;15(3):110–22. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.3.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau J-J. Rousseau J-J. The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [1762] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M. Countervailing Agency: A Strategy of Principled Regulation under Managed Competition. Milbank Quarterly. 1997;75(1):35–87. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00044. 10.1111/1468-0009.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Dennerlein RKH, Kose A, Scholtes L. Health Care in the EC Member States. Health Policy. 1992. 20 (special issues) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scotton R. 1997. Managed Competition: The Policy Context. Working paper 15/99. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne.