We have not lost faith, but we have transferred it from God to the medical profession.

George Bernard Shaw

Writing at the beginning of the 20th century, Shaw identified one of the significant contemporary transformations in industrial democracies. In part as the result of advances in science and technology, in part as a rejection of the monopolistic abuses of industrialization, and in part as a consequence of assiduous efforts by the professions themselves, this was a period in which the legitimacy and social authority of professionals increased dramatically (Brint 1994; Krause 1996; Larson 1977; Sandel 1996). Nowhere was this more evident than in medicine. Over several decades, medicine changed from an occupation with a mixed reputation and little political influence into one that would “dominate both policy and lay perceptions of health problems” (Freidson 1994, 31). In a number of countries, the professional authority and political influence of physicians also rose during this era (Coburn, Torrance, and Kaufert 1983; Krause 1996; Stone 1980), most dramatically in the United States (Starr 1982). Driven by the Jacksonian populism of the mid-19th century, policymakers had largely rejected the legitimacy of professional expertise and stripped away regulations that had supported professional authority (Haskell 1984a). But by the late 1890s, their skepticism was waning (Starr 1982). In two more decades, the medical profession could virtually dictate most state-level policymaking involving health and could strongly influence policy development at the federal level (Bjorkman 1989; Larson 1977; Meckel 1991).

From a vantage point 100 years after Shaw's pronouncement, the authority of the medical profession in the United States can be depicted as a grand historical arc, rising to great heights by midcentury but faltering badly as the century drew to a close. In his recent book comparing the professions cross-nationally, Elliot Krause characterized American medicine as “the fall of a giant.” Summarizing its track record for the entire 20th century, Krause concluded that “no profession in our sample has flown quite as high in guild power and control as American medicine, and few have fallen as fast” (1996, 36).

This loss of medical authority is reflected in the decline of public confidence in the medical profession (Blendon, Hyams, and Benson 1993; Jacobs and Shapiro 1994b). It also is evident in the changing attitudes of policymakers. Once deferential to professional guidance in policymaking, politicians now have begun to question and even alter organized medicine's political stances. During the debate over the Clinton administration's Health Security Act, for example, the Republican leadership in Congress pressured the American Medical Association to withdraw its initial support for certain parts of the act (Skocpol 1996). Past research in political science suggests that the relationship between elite and public perceptions of the medical profession can offer important clues about the origins of changes in professional authority (Page and Shapiro 1992).

The dramatic and persistent nature of these declines has certainly not been lost on academic and other observers. This loss of medical authority has been implicated in a variety of important policy consequences, ranging from the rise of managed care to the failure of particular types of health care reforms (Brinkley 1998; Southon and Braithwaite 1998). Despite the perceived importance of these changes, there is not much empirical research that might help explain their origins (Blendon et al. 1993; Pescasolido, Tuch, and Martin 2001). We therefore know little about what might have undermined public confidence and virtually nothing about the questioning of medical authority by policy elites, let alone the relationship between public attitudes and elite perceptions.

This article addresses these gaps in our knowledge, identifying the particular attitudes and perceptions most closely associated with doubts about medical authority. Because the data used for these analyses were collected at a single point in time, we cannot use them to explain either the timing or the magnitude of past declines in professional legitimacy. These data, however, were collected at the nadir of popular support for medical authority, so they may enable us to identify the most salient threats to professional status. Because this study draws on surveys and interviews that asked identical questions of the general public and policy elites, it also offers an opportunity to compare their assessment of and doubts about medical authority. (Throughout this article, I use “policy elites” and “political elites” as they are used conventionally in political science, to refer to those actors directly forming or implementing public policies. These actors are not, therefore, necessarily a part of the “social elite” as it would be ordinarily understood by sociologists.)

To lay the groundwork for this empirical exploration, I begin by documenting the nature of the decline in medical authority in the United States since the 1960s. I then turn to the literature on professions and professional practice. From this literature, I have identified 13 factors, grouped into four conceptual categories, that might have encouraged the decline in medical authority. These become the hypotheses that are tested in the later sections of the article.

Documenting the Decline in Medical Authority

Although the challenges to the authority of American medicine have been extensively discussed in the sociological literature, the timing and extent of the decline in authority remain controversial (Pescasolido et al. 2001). In the early 1970s, antagonism toward medical authority (and professional authority more generally) had already become evident (Haskell 1984a). Some authors argue that “medicine, like many other American institutions, suffered a stunning loss of confidence in the 1970s” (Starr 1982, 379). Yet other observers dispute this, suggesting that medicine retained considerably more public confidence than many other political or social institutions had (Freidson 1985). The professions in general retained considerable influence over policymaking, even as they faced more overt criticism.

Everywhere in the United States the professions have reached new heights of social power and prestige … yet everywhere they are also in trouble, criticized for their selfishness, their public irresponsibility, their lack of effective self-control, and for their resistance to requests for more lay participation in the vital decisions professionals make affecting laymen.

(Barber 1978, 599)

By the 1980s, most observers acknowledged the decline in medical authority. Both sociologists (Ritzer and Walczak 1988) and doctors themselves (Reed and Evans 1987) were warning of a “deprofessionalization” of American medicine. By the end of the 20th century, professionalism in medicine was being described as a “faith that failed” (Brinkley 1998). Some observers were writing seriously about the “end of professionalism,” noting that the cross-national wave of health policy reform in the 1990s had “been brought about in an environment of widespread attacks on professionalism with little appreciation of the role that professionalism plays” (Southon and Braithwaite 1998, 26).

“Deprofessionalization” refers to physicians’ losses of both autonomy and authority. The growing prevalence of constraints on medical autonomy in the form of utilization review, contractual provisions, and other managed-care practices has been extensively studied (Cartland and Yudkowsky 1992; Cunningham, Grossman, Peter, et al. 1999; DeMaria, Engle, Harrison, et al. 1994; Grumbach, Osmond, Vranizan, et al. 1998; Hillman 1990; Remler, Donelan, Blendon, et al. 1997; Schlesinger, Gray, and Perreira 1997; Schlesinger, Wynia, and Cummins 2000). There has been much speculation about whether this loss of autonomy was a cause or a consequence of the declines in medical authority. But directly measuring attitudes related to medical authority has proven to be difficult, with findings that are less consistent than those related to professional autonomy.

This ambiguity is evident in the data available from public opinion surveys. Three survey firms—the National Opinion Research Corporation or NORC (through the General Social Survey), Harris, and Gallup—have surveyed the public on attitudes toward the health care system, repeating questions about confidence in either the system generally or those who “lead” it.1 Although these questions do not, therefore, ask directly about professional legitimacy, they have been widely interpreted as offering insights into the public's acceptance of medical authority (Blendon et al. 1993; Haskell 1984a; Jacobs and Shapiro 1994b; Pescasolido et al. 2001).

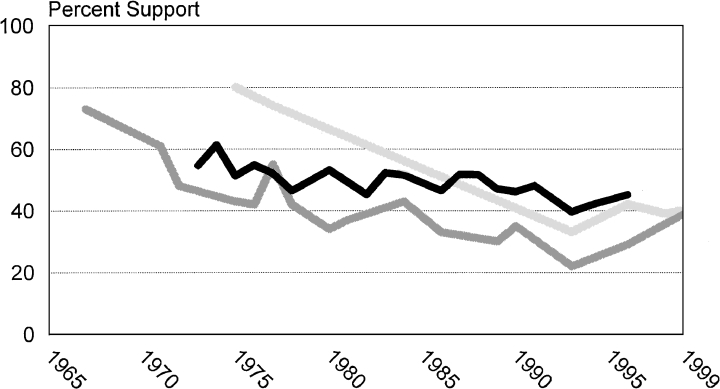

The data from these three sources are presented in figure 1. The responses on all three time series suggest a waning of public confidence dating back to the early 1970s, with the NORC and Harris data beginning to diverge in the mid-1970s. Between 1975 and 1995, public confidence in medical authorities measured on the General Social Survey was relatively stable. Researchers who have analyzed these data have therefore concluded that the decline in public confidence in the medical profession was no greater than that experienced by various other American social institutions (Pescasolido et al. 2001). In contrast, the Harris data indicate a larger and more sustained loss of medical authority. Researchers using these data have decided that the loss of professional legitimacy in American medicine was far more pronounced than that experienced by other social institutions. These surveys suggest that over a 30-year period, American medicine went from being perhaps the most trusted to being one of the least trusted social institutions (Blendon et al. 1993).

fig. 1.

Loss of public faith in the authority of the medical profession. These survey results show the percentage of the American public expressing confidence in medical leaders. For the Harris and NORC results, confidence is the percent responding “a great deal”; for the Gallup results, it is “a great deal” and “quite a lot. ” █ = NORC; ▒ = Harris; ░ = Gallup.

The gap between the Harris and NORC findings remains puzzling, given the similarity of the questions’ wording. In any case, all three sources of data indicate at least some decline in medical authority, though it remains unclear whether this can be attributed to particular assessments of the performance of American medicine, as opposed to more general questions about trust in social institutions. There also appears to be some consistent evidence that public confidence in medical authority rebounded a bit in the mid-1990s, perhaps reflecting the early stages of the “managed care backlash” that turned the public against intrusions into clinical autonomy (Blendon, Brodie, Benson, et al. 1998). Nonetheless, confidence in the medical profession remained well below the levels documented in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

No comparable time series measure the attitudes of policy elites toward the medical profession. A somewhat comparable measure, however, can be derived from the testimony presented at congressional hearings. As part of a larger research project, a team of researchers analyzed the content of these hearings at four different times: the mid-1960s (the enactment of Medicare), the mid-1970s (debates over national health insurance), the late 1980s (a variety of health-reform issues), and the early 1990s (the Clinton administration's health-reform proposals). For each of these sets of hearings, the abstracted information can be used to determine the extent to which the testimony invoked notions of professional medicine to garner legitimacy for particular strategies of health care reform.

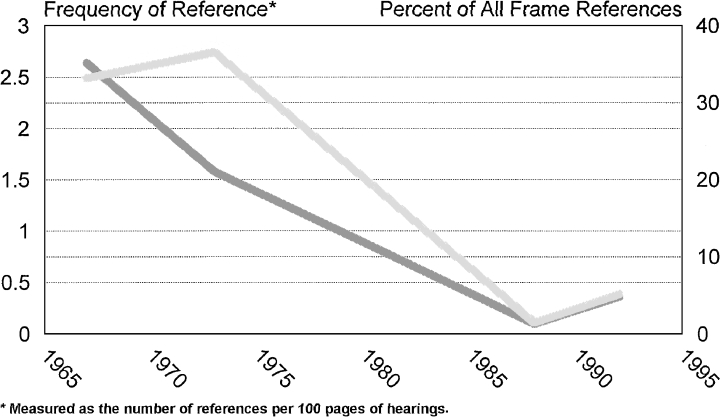

The results from these analyses are presented in figure 2, measured in two different ways. The first counts the total number of legitimizing claims based on professional authority, per 100 pages of (written and oral) testimony. The second measure counts the frequency with which the professional medical frame is invoked in testimony, compared with other legitimizing frames. By either measure, the decline between the 1970s and late 1980s in elites’ use of the professional frame to rationalize health care reform is dramatic. It is difficult to assess accurately the timing of the turning points, given the extended periods during which there were few congressional hearings related to health care reform. Nonetheless, it appears that the elite use of the professional frame may already have been on the upswing by the early 1990s, during the debate over the Health Security Act. As with public opinion, however, elite use of a professional frame to legitimize reforms remained much less common during the 1990s than it was in earlier debates. (Corroborating evidence can be found in the historical comparisons presented by Skocpol (1996) and Johnson and Broder (1996), each of which contrasted the Clinton-era reform debates with previous debates over national health insurance.)

fig. 2.

Loss of elite faith in the authority of the medical profession. Faith is measured by the prevalence of professional service frames in congressional hearings. ░ = number of references; ▒ = proportion of all legitimizing frames.

Although these measures of professional legitimacy for both the public and elites obviously are limited, they further document the substantial decline in the confidence in the American medical profession in the late 20th century. But measures of this sort cannot provide many insights into why doubts about professional legitimacy began to emerge, nor can they tell us much about the relationship between elite and public attitudes. Although there is evidence that the rebound in professional legitimacy during the 1990s occurred first among elites, it is difficult to discern from these sorts of turning points whether elite assessments are really “trickling down” to affect public attitudes (Zaller 1992). To gain more insights into the nature of the threats to the professional legitimacy of American medicine, we need to consider more carefully the potential sources of doubt about medical authority.

A Conceptual Framework for Assessing the Determinants of Professional Legitimacy

Because the literature uses the terms “medical dominance” and “medical authority” in different ways, I begin by explaining how they are used in this article. I refer to “authority” as the influence of the profession over collective allocations of health care resources, that is, directly shaping government policies. This influence might also be reflected in policymakers’ willingness to allocate resources to medical professionals. Our focus on professional influence over collective decisions contrasts with much of the past writing on medical dominance, which emphasizes authority in clinical practice, that is, the extent to which patients, insurers, or other key decision makers defer to physicians in judging when particular forms of treatment are appropriate (Freidson 1994; Mechanic 1991). These different forms of medical authority may well be related to one another but may have distinctive determinants.

Authority can emerge from either promised benefits or implied threats. As Paul Starr put it, “Authority, therefore, incorporates two sources of effective control: legitimacy and dependence. The former rests on the subordinate's acceptance of the claim that they should obey; the latter on their estimate of the foul consequences that will befall them if they do not” (1982, 9). Historically, authority in American medicine has derived primarily from professional legitimacy, the ability of physicians to argue persuasively that they should have influence over policymaking. This is less often true in other countries, where physicians have been more apt to organize work stoppages or other collective actions if they feel that their interests are being unduly slighted (Coburn et al. 1983; Krause 1996; Wilsford 1989). Our analysis of American attitudes therefore focuses on the legitimacy of professional influence over policymaking, as perceived by the general public and policy elites.

Hypothesized Threats to Professional Legitimacy in Medicine

In order to assess empirically the sources of flagging medical authority, we must first identify the potential threats to that authority. In sociology, history, political science, bioethics, and medicine, three distinct analytic approaches address the nature of these threats. The first studies the rise of professional authority in the early 20th century. Although this work emphasizes the conditions that first allowed physicians to establish their dominance, when these conditions later changed, it seems plausible to expect that professional authority would diminish as well. The second set of studies discusses anecdotal accounts of contemporary losses of professional authority. The third literature examines the emergence of new ideas governing American health policy over the past half century, including the growth of medical consumerism and notions of a societal right to medical care.

One can derive from these varied disciplinary and historical perspectives more than a dozen testable hypotheses. I will group these into four broad categories, or “core hypotheses.” Several of these core hypotheses closely match Parsons's (1951) seminal discussion of the professions’ social functions.

Core Hypothesis 1: Doubts about Professional Efficacy

At the heart of medical authority is the notion that physicians possess a distinctive knowledge that is relevant to decisions about the appropriate treatment of health problems, a notion that corresponds to Parsons's ideas about expertise and achievement orientation among professionals. Historians have documented the episodes in which the status of early medical practitioners was powerfully shaped by their ability (or lack thereof) to respond effectively to plagues and other forms of pestilence (Krause 1996). The emphasis on expertise as a source of medical authority grew even stronger in the early 20th century, when allopathic physicians used evidence of better outcomes to win legitimacy away from other schools of medical thought (Larson 1977; Rothstein 1972; Starr 1982). As the century progressed, medical professionals increasingly invoked science to legitimize their claims to authority (Brint 1994).

This source of authority has been challenged in recent decades. The growing awareness of errors in medical judgment and of the widespread variation in the prevalence of procedures have led to questions about medical expertise or doubts about the ability of physicians to allocate resources in accordance with true health needs (Gray 1992; Leape 1994). Although this evidence had begun to emerge by the 1970s (Barber 1978; Haskell 1984b), it seems to have had greater influence on policymaking in the 1990s (Gray 1992; Southon and Braithwaite 1998). Also during this period, both the public and policy elites began to accept that certain health behaviors (e.g., smoking, lack of exercise) might at least partly invalidate a person's claim to collective resources for treating medical conditions (Schlesinger and Lee 1993). These notions of “deservingness” represent an additional challenge to the criterion of need, indirectly undermining physicians’ claims to authority.

Taken to their logical conclusions, these concerns raised questions about the efficacy of societal investments in medical care, compared with other interventions that might improve the population's health (Evans and Stoddart 1994). In addition to these concerns specific to medical care, physicians’ collective legitimacy may have been further compromised by a declining faith in science and technology generally (Brinkley 1998; Brown 1979; Fox and Firebaugh 1992; Larson 1984; Starr 1982).

Core Hypothesis 2: Questions about Professional Agency

Historically, a second source of authority is the belief that professionals will act as reliable agents, subordinating their own self-interest and normative judgments to their clients’ well-being. This motive was given a variety of labels during the 20th century. It was originally referred to as “professional disinterest” (Haskell 1984b), later as “moral authority” (Starr 1982), and still later as the profession's fiduciary role (Rodwin 1993) or trustworthiness (Mechanic 1996). This professional disinterest corresponds to two of Parsons's dimensions of prototypical professions: an altruistic orientation and value neutrality. Although members of the medical profession generally welcome this agency role (Barber 1978), whether physicians should be acting in the interests of their individual patients, society as a whole, or some combination of the two remained ambiguous (Burnum 1977; McGuire 1986).

The tensions between individual and societal agency became more pronounced as policymakers grew more concerned with the aggregate costs of medical care. In attempting to balance cost containment against patient welfare, the medical profession was increasingly criticized for failing to achieve either objective. On the one hand, physicians were accused of a profligate use of resources that drew money away from other needed services (Krause 1996; Light 2000; Southon and Braithwaite 1998) and of practices that, in the words of one critic, “abuse the patient and the society economically” (Goldsmith 1984, 13). (The authority of Germany's medical profession was challenged on the basis of similar concerns about societal costs during the 1970s; see Stone 1980.) Policymakers regarded this wasteful use of medical resources as threatening the solvency of government-run health programs, a concern that was exacerbated by well-publicized cases of physicians fraudulently billing Medicare and Medicaid (Gray 1991; Haskell 1984a; Starr 1982). The public also began to believe that “profiteering” by physicians accounted for much of the skyrocketing costs that were making health insurance increasingly unaffordable (Immerwahr, Johnson, and Kernan-Schloss 1992).

Ironically, when physicians try to take into account concerns about cost, they undercut professional legitimacy in a second manner. During the 1980s, physicians were increasingly accused of compromising the care of their patients in the name of cost containment (Agich 1990; Rodwin 1993; Wolinsky 1993). Unable to articulate a clear principle for balancing the needs of their patients against those of society, the profession was caught in a classic double bind.

Questions about professional agency were reinforced by the growing supply (in some locales, a virtual glut) of physicians. After remaining roughly constant at 130 per 100,000 residents for the first half of the 20th century, the supply of physicians grew dramatically after 1960, reaching 151 per 100,000 residents in 1970, 202 per 100,000 in 1980, and almost 300 per 100,000 in 1990 (Krause 1996, 45). Apart from reducing physicians’ bargaining power relative to that of other actors, the pressures of a more competitive marketplace fostered commercial practices that deepened the public's doubts about physicians’ motives (Brint 1994; Hanlon 1998). Perhaps the clearest example of problematic practices was a commercial arrangement between the American Medical Association and the Sunbeam Corporation through which the AMA endorsed Sunbeam products (Stevens 2001). The public response to this episode was extremely negative, leading to the firing of three AMA executives. (Since the episode occurred in 1997, however, it could not have influenced the attitudes measured in this study.)

A more pervasive case in point is advertising by physicians. Before the late 1970s, direct advertising (apart from listings in phone directories) had been prohibited by the AMA's code of ethics. In 1978, professional restrictions of this sort were overturned by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the ethical code for lawyers, a ruling that was soon extended to the medical professions as part of a Federal Trade Commission consent decree. With market competition growing, advertising soon became common. By 1982, 28 percent of the American public reported having seen an advertisement by a physician (based on survey data collected by the American Medical Association and available from the Roper Center on Public Opinion at the University of Connecticut; the particular question on exposure to physician advertising is cataloged with accession no. 0075753). Thirty-five percent of the public at that point considered such advertising “unethical,” and 31 percent reported that they felt that advertising made doctors “less professional” (Roper Center accession nos. 0075754 and 075758, respectively). Given these attitudes, exposure to advertising likely further undermined the profession's already shaky public reputation. By the end of the 1980s, physician advertisements had become quite common, but the public remained skeptical of them. In a survey conducted in 1988, 40 percent of the respondents expressed doubts about whether it was “ethical and proper for doctors to advertise” (Roper Center accession no. 0129851).

The increasing commercialization of the medical marketplace also raised questions about physicians’ purportedly altruistic motives (Stone 1997; Wynia, Latham, Kao, et al. 1999), including their emphasis on caregiving in preference to conventional business practices (Barber 1978) and their willingness to treat indigent patients (Brint 1994; May 1983)

In order to compete in today's more market-oriented medical system, physicians are going to be forced to emphasize business practices more with the result that professionalization may suffer … with physicians advertising their services on television and in the newspapers, it will be harder for them to continue to put forth an altruistic image. Patients are more likely to question authority of physicians selling their services side-by-side with used car salespeople.

(Ritzer and Walczak 1988, 10–11)

Core Hypothesis 3: The Rise of Countervailing Authority

Quite apart from the perceived performance of the medical profession, some observers argue that its legitimacy has been further challenged by the growing influence of other parties with agendas that conflicted with those of the medical community (Light 1995; Stevens 2001). Between 1970 and 1995, three potential sources of countervailing authority were identified in the literature: (1) a greater role for the government in the health care system, (2) the more active presence of employers purchasing health care and health insurance, and (3) the empowerment of individual patients (aka the “consumers” of medical care). The logic of this argument rests on the notion that allocative decisions about medical resources involve a relatively fixed amount of authority and legitimacy, so an increase in the authority of one party necessarily diminishes the authority of the others. This is a notion that seems more likely for some types of challengers to the medical profession than for others.

Given the multiple roles for government in contemporary American medicine and the widespread public support for its involvement (Jacobs and Shapiro 1994a), it is easy to forget that before the 1960s, the public sector had very little involvement in medical care. Should we expect an increase in the government's authority to undermine the legitimacy of the medical profession? Certainly the American Medical Association warned about this threat in its campaigns against both national health insurance and the Medicare program (Marmor 1973; Numbers 1978; Starr 1982). But international experience makes these fears seem implausible. The medical profession possesses considerable authority in those countries in which the national government plays an extensive role in medical care, whereas physicians have less influence in those countries in which the central government control is weak (Bjorkman 1989; Coburn et al. 1983; Freidson 1994; Krause 1996; Lane and Arvidson 1989).

More plausibly, the impact on medical authority depends on the form of government intervention (Johnson 1995; Light 2000). If the government were to directly regulate medical practice itself or the allocation of health care resources, perceptions of medical professionalism might well be undermined, with individual physicians’ discretion replaced by bureaucratic standardization (Hanlon 1998). But this is not the form of government involvement that has been followed in the past in the United States, nor one likely to be supported by the American public (Skocpol 1996). Most Americans favor government financing for medical care, along with some general rules for resource allocation, such as found in the Medicare program. Under these arrangements, the authority for medical decisions is delegated to health care professionals. This form of government involvement seems just as likely to enhance professional legitimacy as it is to undermine it (Light 2000).

A second source of countervailing authority appears to be a more plausible threat to the medical profession: the role of employers in the health care system. Although employers’ involvement in American medical care can be traced back to the 18th century, the role of employers burgeoned after World War II as health insurance became an important fringe benefit of employment (Field and Shapiro 1993; Silow-Carroll, Meyer, Regenstein, et al. 1995). Over the past few decades, employers’ involvement has begun to challenge physicians’ authority more directly. As costs soared in the 1970s and employees sought help in choosing among physicians and health plans, companies began to manage their health benefits more actively (Crawford 1979; Reiser 1992; Salmon 1975). This more active involvement was accompanied by a growing skepticism of professional motives and practices:

American business leadership has been highly critical of the performance of the medical profession. At times physicians have been portrayed as the culprits in health cost inflation, which has crimped corporate profit levels. Forbes, the business magazine styling itself as “the capitalist tool,” led off a 1977 cover story article entitled, “Physician Heal Thyself … Or Else” with these words: “If doctors don't choose to change their business ways, they have reason to fear that they may be ordered to do so.” … From lobbying by the Washington Business Group on Health and other corporate planning bodies to business coalitions all across the country putting the muscle on local providers, corporate purchasers of care now exert a powerful external force that was unfelt in health care prior to the 1970s.

(Salmon 1987, 24)

A third potential source of countervailing authority is the increasingly active role for patients as both individuals and organized groups (Katz 1993; Turner 1995). Beginning in the early 1970s, a consumer movement was organized to address medical care decisions (Rodwin 1994). Much of the early and most successful organizing pertained to women's health care, reflecting a significant gender gap in assessments of the quality of physician-patient relationships (Weisman 1998). Groups affiliated with this movement were in the forefront of challenging physicians’ dominance (Salmon 1987; Starr 1982), and their concerns began to reshape public opinion more generally (Haug 1988), leading some physicians to complain that “many patients have come to regard professionally rendered medical advice suspiciously, or as superfluous” (Reed and Evans 1987, 3280). Because physicians tended to underestimate the extent to which patients did want information and control over medical decision making, their misguided practices further reinforced doubts about their motives as agents (Waitzkin 1985).

The growing influence of employers and the transformation of patients into “informed consumers” thus appear to be the most realistic threats to the authority of the American medical profession. During the second half of the 1980s, state and federal policymakers implemented policies to offer even more choices to consumers and even more aggressive roles to employers, seeing in these developments the possibility of injecting even more cost-sensitive decisions into American medicine (Marmor and Boyum 1993). By so doing, policymakers harnessed government intervention to assist the primary challengers to medical authority. As a result, by the close of the 20th century, more active government engagement in health care may also have become associated with a salient threat to professional control over health care resources.

Core Hypothesis 4: The Violation of Professional Boundaries

The final possible threat to medical authority stems from the very fact that the medical profession was so powerful in the past. In the process of exerting this influence, physicians may have been seen as overreaching, going beyond their appropriate domain of expertise and inappropriately imposing their judgment on areas best left to other societal institutions (Light 1995). This concern corresponds to Parsons's notions of functional specificity and perhaps also to certain aspects of value neutrality.

Since the Jacksonian era, Americans have suspected that professional authority carried with it the threat of disempowerment for the general public (Krause 1996; Larson 1977). These tensions have often been most evident in local communities, where the medical establishment may control resources that might otherwise have been diverted to various social or environmental factors that affect population health more than does access to medical care (McKnight 1995). Historically, policy initiatives intended to encourage greater community participation in decisions allocating health care resources have often foundered in the face of opposition from the medical profession (Krause 1996; Larson 1984; Morone 1990; Schlesinger 1997). Given this history, it is not surprising to find that elite proponents of community involvement are less than enthusiastic supporters of professional authority. As policymakers over the past decade have recognized the value of a more community-oriented medical care system, this goal may have further undermined their faith in professional authority (Emanuel and Emanuel 1997; Schlesinger and Gray 1998; Spitz 1997).

On a more public level, the medical profession may also have been weakened by its more overtly political activities. For example, the AMA's active opposition to the enactment of Medicare in the 1960s seems to have engendered considerable public resentment (Stevens 2001). “Community sentiment, which had generally been in favor of the medical professions, began to change. People still trusted their own doctors—if they had one—but they began to view the profession as a whole as greedy and heartless” (Krause 1996, 43). There certainly is evidence from other countries that when the medical profession becomes too active politically, this can produce a popular backlash that undermines the legitimacy of the profession (Stone 1980). We might expect to see these tensions manifested in two distinct attitudes: first, a lack of public trust in the political activities of organized medicine and, second, a perception that the medical profession is exerting undue influence over the political process.

The Relationship between Elite and Public Reactions to Medical Authority

Our review of the literature has identified 13 hypotheses about threats to medical authority, grouped into four categories (table 1). Some of these potential threats reflect widespread shifts in prevailing societal norms, such as the growing doubts about science or the increasing acceptance of an active role for government in the health care system. Because these are deeply rooted in American society, we would expect them to be reflected in the attitudes of both the general public and policy elites.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Hypothesized Threats to the Political Legitimacy of the Medical Profession

| Core Hypothesis | Specific Sources of Declining Legitimacy |

|---|---|

| Core Hypothesis 1: Doubts about Professional Efficacy | 1. Medical care is seen as not effective or reliable. |

| 2. “Health needs” are no longer seen as the appropriate standard for allocating medical resources. | |

| 3. There is a general loss of faith in science and technology. | |

| Core Hypothesis 2: Questions about Professional Agency | 1. Physicians are thought to have become unduly money oriented. |

| 2. Physicians are seen as more concerned about controlling costs than about protecting the interests of their patients. | |

| 3. Physicians are no longer thought to be committed to meeting the needs of the populations that they serve. | |

| 4. Physicians are no longer thought to care for unprofitable patients. | |

| Core Hypothesis 3: The Rise of Countervailing Authority | 1. Support grows for the government to be more active in the health care system. |

| 2. Support grows for more active employers in the health care system. | |

| 3. Support grows for a more active role for individual consumers of medical care. | |

| Core Hypothesis 4: Violation of Professional Boundaries | 1. Belief widens that communities should have control over health care. |

| 2. Lack of trust in the political activities of the medical establishment increases. | |

| 3. Physicians are seen to have too much political influence over policymaking. |

Other hypotheses, however, may prove to be more salient to either the public or elite decision makers. Historians have documented how efforts to build professional legitimacy for physicians at the beginning of the 20th century relied on different strategies for shaping elite and public opinion. “The favor of an elite did not necessarily bring with it wide public support. To equip themselves for the conquest of public confidence was one of the main tasks of the professions during the ‘great transformation’” (Larson 1977, 4). We might expect that contemporary threats to professional legitimacy would also draw on different considerations for the two groups.

Perhaps the most pronounced difference between policy elites and the general public rests in their knowledge about substantive matters relevant to health policy issues. Most of the American public is largely ignorant of both public policy in general (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996) and health policy in particular (Blendon et al. 1993). More knowledge about health policy can be expected to exacerbate certain threats to medical authority while partially ameliorating others.

For this reason, we would expect that four of these hypothesized threats would be greater among more knowledgeable decision makers. The first is that physicians might be placing a higher priority on cost containment than on the well-being of their individual patients. This concern is largely linked to the growing use of financial incentives by managed care plans, which can create powerful inducements to withhold treatment (Hellinger 1998). Much of the public, however, remains unaware of the ways in which physicians are paid by health plans and thus ignorant of the magnitude of this potential concern (Kao, Green, Zaslavsky, et al. 1998; Miller and Horowitz 2000). Three other threats to medical authority should be similarly reduced by the public's lack of exposure to evidence that

Much medical care is inefficacious. Although during the 1980s, policymakers began to question the value of much medical care (Gray 1992), most of the public still believes in the efficacy of medical treatment (Yankelovich 1995).

Important health needs are neglected by the medical community. Although policy elites have come to recognize the importance of the social factors in health outcomes, the public is much less aware that these needs are not addressed by the health care system (Schlesinger and Gray 1998).

Low-income Americans are often denied treatment. Although a substantial portion of the public recognizes the barriers faced by those unable to pay for medical care, many others are less cognizant of these problems (Jacobs and Shapiro 1994b).

Because the general public is less informed about these concerns, we would expect that for them, they would be less salient threats to medical authority. In contrast, other threats may be exacerbated by the public's relative lack of information. Because most Americans fail to recognize the role of technology and other factors driving up health care costs, they tend to place too much blame on health care providers for these cost increases (Blendon et al. 1993; Immerwahr et al. 1992). This could inflate public perceptions that physicians are unduly motivated by monetary concerns.

These five threats to professional authority may differ in salience between the public and policy elites, as a result of the former's lack of knowledge about various aspects of health care delivery. In other cases, elite and public attitudes may differ because the two groups view social or political institutions differently. For example, the perception that physicians have too much political influence is more likely to affect public attitudes toward the profession, since elites are more likely to invoke elaborate “pluralist” constructs that legitimize the activities of various interest groups (Reeher 1996; Verba and Orren 1985).

These differences in public and elite perceptions may well lead to different conclusions about the appropriateness of professional authority over health policy. But even if these differences exist in the first instance, several factors bring elite and public attitudes together. First, some segments of the public are relatively well informed. To the extent that the public's and elites’ differences in attitude are driven by differences in information, we would expect that this better-informed “issue public” would see the legitimacy of the medical profession more as the policy elites do (Page and Shapiro 1992). Second, members of the public may look to the positions taken by politicians or other elites to help them understand complex policy issues (Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Zaller 1992). The higher the profile of a given issue on the political agenda, the more it will be actively discussed and the more readily the public can draw lessons from the pronouncements made by elites.

These considerations suggest that the gap between elite and public judgments about professional legitimacy ought to match the level of sophistication and political engagement of different segments of the public. More knowledgeable members of the public should see medical authority more as the policy elites do. More politically attentive members of the public should emulate more effectively the positions expressed by elites. However, a substantial portion of the public—perhaps a third to a half—is almost completely disengaged from political matters and public affairs, often because they have more pressing personal matters to address or simply have no interest in collective issues (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996; Zaller 1992). If differences in knowledge are the primary determinant of the various attitudes toward medical authority, it is among this least sophisticated segment of the public that the gaps between public and elite assessments should be most pronounced.

An Empirical Exploration of the Levels and Determinants of Medical Legitimacy

To gauge the support for professional authority in health policy among the general public and political elites and to explore the factors that shape this support, we collected attitudinal data from both groups. We obtained this information in 1995 as part of a larger project designed to study the public's and elites’ understanding of public policy (Schlesinger and Lau 2000). This study used two methods of data collection: (1) a survey of the general public (1,527 respondents) and congressional staff (172 respondents) to assess the support for particular strategies of reform and (2) a set of 169 intensive interviews (119 with members of the public, 50 with Washington elites) to explore in more detail the ways in which individuals thought about policy issues. I begin with a description of these samples and then discuss the specific questions used to measure support for professional authority and test the hypotheses.

Sources of Data

Interviews

We interviewed two groups of respondents. The first was a convenience sample of 119 members of the general public. Although we could not randomly draw a sample for this part of the study, we used recruitment strategies (e.g., notices in various community periodicals and meeting halls) that ensured adequate variation in age, socioeconomic status, and political ideology. To reduce the idiosyncratic influences of residence in a particular community, participants were drawn from five sites located in four states—Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Fifty-five percent of the subjects were female, and 17 percent were nonwhite, with an average age of 45 and a median education of 11.5 years. The participants were more educated than the average American and more liberal in ideology (reflecting regional political norms), though in both cases there was sufficient variation to explore the implications of these characteristics for support for medical authority. To ensure that unrepresentative characteristics of this sample did not bias subsequent conclusions, our analyses controlled for the ideological orientation of the interview subjects, along with other sociodemographic characteristics.

We selected the elite sample to identify individuals sophisticated about health policy. The sampling frame was divided into representatives of provider associations, patient groups, industry, and government, and a random sample was drawn from these groups. Congressional staff and officials in the executive branch were selected according to their participation in the formulation of the Health Security Act. Representatives of interest groups were identified from a published compendium of such individuals considered influential in policymaking (Faulkner and Gray 1995). We interviewed a total of 50 elite respondents, a response rate of 76 percent.

Survey Methods for Assessing Public Opinion

The public opinion survey was based on a random sample of households containing at least one adult over the age of 18, fielded using random digit dialing from July 6, 1995, through August 1, 1995. After taking into account ineligible (e.g., business or inactive numbers), the survey had an overall response rate of a little more than 69 percent, yielding 1,527 interviews. Item nonresponse ranged from 0.5 percent to 3.9 percent.

The interviews required, on average, 35 minutes to complete (the noncompletion rate was less than 1 percent). They covered attitudes toward the salience of problems and preferred policy responses in a number of difference policy domains, including medical care, long-term care, treatment of substance abuse, and “basic needs” (defined as food, shelter, and other necessities). The alternative policy approaches that respondents were asked to assess included uniform national programs modeled after the Social Security system, employer-based arrangements, and market models relying on vouchers. To ensure that the order of the questions did not affect the respondents’ choices among policy alternatives, the policy alternatives were presented in a randomly determined order for each respondent. Information was also collected on respondents’ attitudes toward distributional justice, the efficacy of government programs and the policymaking process, as well as the appropriate role for the federal government in addressing societal problems.

The survey respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics generally matched those of the adult American population in terms of education, marital status, gender, and household size. The proportion of low-income African American and Latino respondents was about a third lower than expected for a representative sample. Again, however, low-income minority groups were sufficiently represented to test for differences in their responses.

Survey Methods for Assessing Attitudes of Congressional Staff

All congressional staff responsible for health care were identified through published directories. They were subsequently contacted by telephone and asked to participate in the study. Surveys were completed between June and October 1995. Taking into account those respondents who were ineligible because they were participating in other aspects of this study, the overall participation rate was approximately 35 percent, yielding a total of 172 completed interviews. Of those who did not participate, slightly more than half reported that they could not as a result of office policy. A subsequent analysis of respondents and nonrespondents suggested no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of the ideological position of the member for whom they worked (assessed using both the published Americans for Democratic Action ratings of overall liberalism in voting and the National Journal ratings of liberalism and conservatism on domestic policy issues (Barone and Ujifusa 1995)), the proportion of their constituents who voted for Clinton or Bush in 1992, the length of time their member had been in Congress, or the member's margin of victory in his or her last election.

The survey of congressional staff was structured to replicate much of the survey of public opinion, including the randomly ordered presentation of reform alternatives within each policy domain. In addition to the questions asked of the general public, staffers were asked about the importance of particular policy concerns for their constituents, the impact of those issues on the electoral prospects for their member, and the challenges of communicating about those issues with constituents. Item nonresponse ranged from 0.6 percent to 6.5 percent.

Measuring Support for Medical Authority

Measures from the Interviews

The interviews explored a variety of strategies for health care reform. As part of this inquiry, we asked the interview subjects a set of closed-ended questions about each strategy. Three responses serve here as measures of support for professional authority. First, subjects were asked (on a five-point scale) the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement “The best solutions to our country's health care crisis can be found by relying on those who provide health services.” Second, agreement was measured for the statement “The health care system would work better if doctors had full control over the system.” Third, after having been asked about various statements describing the role of physicians in American medicine and health policy, the subjects were asked about their general support for health reforms that delegated authority for allocating medical resources to groups of doctors. The response (also on a five-point satisfaction scale) to this deliberately more ambiguous stimulus was intended to evoke a more generalized reaction to professionalism in health care.

Measures from the Surveys

Respondents on the survey were also asked to assess a variety of strategies for reform, in both health care and other policy domains. The medical care reform most closely oriented to professional control was described as follows: “People would sign up with groups of physicians, who would be paid a fixed amount for each enrollee by the federal government. The physicians in each group would decide what was covered and how best to spend the money available for health care.” Each of the policy alternatives explicitly stated that funding would come from the federal government, so as to ensure that choices among reform alternatives would not be influenced by preferences in financing medical care. Respondents were asked to provide a general reaction to this approach in terms of support or opposition. In addition, they were asked to assess (on a five-point scale ranging from very positive to very negative) the implications of this reform option for “the country as a whole” as well as for various subpopulations.

The measure of support and assessment of implications captures different aspects of enthusiasm for professional control. Although support for professionally controlled reforms was asked in absolute terms, because it was part of a sequence of reform options, the responses were undoubtedly influenced by the other reform strategies to which the respondents were exposed. It thus makes sense to think about these responses as capturing support for professional control relative to the other reform options. In contrast, the respondents’ predictions about the impact of professionally controlled reforms on the country as a whole more likely captured their assessments in absolute rather than relative terms.

Measuring the Hypothesized Threats to Medical Legitimacy

By combining responses from the interviews and surveys, we identified measures to test each of our 13 hypotheses. For some hypotheses, measures from interviews and surveys captured different aspects of the attitude or perception in question (table 2). For other hypotheses, measures were available from either the interviews or the surveys. In this section, I first review these measures and then identify some other political attitudes and sociodemographic factors that need to be statistically controlled in order to measure accurately the influence of our hypothesized attitudes on support for medical authority.

TABLE 2.

Attitudinal Measures Predicting the Political Legitimacy of Physicians

| Hypotheses about Declining Legitimacy | Specific Measures from Interviews | Specific Measures from Surveys |

|---|---|---|

| Core Hypothesis 1: Doubts about Professional Efficacy | ||

| Medical care is ineffec tive. | None | Disagree that “adequate health care is essential for there to be equal opportunity.” |

| Need is not an appropriate standard. | Disagree that “people should get health care based on needs.” | None |

| Faith in science has been lost. | None | Disagree with allocating services to meet “basic needs” using “scientifically correct answers”. |

| Core Hypothesis 2: Doubts about Professional Agency | ||

| Physicians are commercially oriented. | Agree that providers are “self-interested and out to make money from medical problems.” | None |

| Physicians are too sensitive about medical costs. | Agree that “doctors no longer place your well-being above concerns about health care costs.” | None |

| Needs are not held foremost. | Agree that providers “are no longer committed to meeting the needs of communities.” | None |

| Physicians do not care about the poor. | None | Agree that a physician-run health care system would be worse for the poor than would a system run by the federal government. |

| Core Hypothesis 3: The Rise of Countervailing Authority | ||

| The federal government's role in health care should be supported. | Agree that “you need national solutions” to address the problems of the current American health care system. | Agree that “it is the responsibility of the government in Washington to help people pay for doctor and hospital bills.” |

| Employers’ involvement in health care should be supported. | Agree that the American health care system would work better if “workers and managers bargain with one another to decide on health benefits.” | Favors greater influence by business interests over “government health policies and programs.” |

| Medical consumerism should be supported. | Agree that “each person ought to make the choices” about health care. | Agree that medical care is “not the responsibility of the federal government” and that “people should take care of these things themselves.” |

| Core Hypothesis 4: Violation of Professional Boundaries | ||

| Community involvement should be supported. | Agree that solutions to health problems are best found by “local government or community-based groups.” | Agree that allocating medical care through community-based groups would be “good for the country as a whole.” |

| Physicians’ political influence is worrisome. | Disagree with the claim that most people are “comfortable having physicians guide policymakers” about health policy. | None |

| Physicians’ political influence should be reduced. | None | Agree that physicians have too much influence over “government health policies and programs.” |

Measuring Attitudes That May Affect Acceptance of Medical Authority

I identified three attitudes related to perceptions of medical efficacy: (1) questions about the effectiveness of medical care in achieving certain socially desired outcomes, (2) doubts about the appropriateness of “need” as a criterion for allocating health care resources, and (3) a more general loss of confidence in the value of “scientific” solutions to contemporary social problems. Our measure of the perceived effectiveness of medical care is an indirect one, drawn from the surveys. It has often been argued that access to medical care is a prerequisite for equal opportunity (Daniels 1985; Dougherty 1988), a claim that assumes that medical care has a beneficial effect on social functioning. Those who doubt the essentiality of medical care also are likely to question the efficacy of treatment. Thus we measured the extent to which survey respondents agreed that “adequate health care is essential for there to be equal opportunity in the United States.”

The interviews provided the measure of the appropriateness of the need criterion. The subjects were asked whether they agreed that “people should get health care based on needs as determined by medical experts.” Those who disagreed likely had more doubts about medical authority. The surveys provided the measure of general confidence in science. The respondents were asked whether resources should be allocated to meet the “basic needs” of the American population on the basis of decisions by experts “who can find scientifically correct answers.” Again, a negative response could be associated with diminished professional legitimacy.

I identified from the literature four factors that might raise questions about professional agency: (1) concerns that physicians were unduly motivated by personal financial gain, (2) perceptions that physicians place cost containment above the interests of their patients, (3) doubts about health professionals' commitment to meeting health needs, and (4) fears that physicians are no longer willing to take care of indigent patients. Questions relevant to the first three of these perceptions were asked in the interviews, and attitudes that could indirectly measure the fourth concern were captured in the surveys.

Concerns about physicians’ commercial motivations were measured by the respondents’ agreement that health care providers were “out to make money from medical problems.” Fears about the impact of cost-containment pressures were revealed in the agreement that “the biggest problem with American medicine is that doctors no longer place your well-being above concerns about health care costs.” Questions about commitment to meeting health needs were assessed according to the respondents’ agreement that “the biggest problem with the health care system today is that hospitals and physicians are no longer committed to meeting the needs of the cities and towns where they provide health care.”

Neither the interviews nor the surveys contained questions that directly measured the perception that physicians were unwilling to treat indigent patients. But the surveys did collect information from which we could infer something about these attitudes. Respondents were asked whether they believed that health care reforms that allowed physician-run groups to allocate resources would have a positive or negative effect on “poor Americans.” Those who predicted the latter effect almost certainly doubted the altruistic motivations of most doctors. Because all the questions about health care reform presumed that the reforms would be federally financed, the respondents might have thought that physician-run reforms would have a positive effect because federal funding would subsidize treatment for the poor, not because physicians would be inclined to treat indigent clients. To control for this effect, I compared the respondents’ assessment of the impact of physician-controlled reforms on the poor with their assessment of a single-payer reform strategy. I then used the comparison to determine the extent to which physician control per se was seen as good or bad for patients from low-income households.

Three sources of potentially countervailing power were identified from the literature: (1) the role of the federal government, (2) the role of employers, and (3) the role of empowered consumers. The interviews and surveys provided the measures of support for each of these other actors. The respondents in the interviews were deemed to favor a more active role for these other three actors if they agreed that either (1) the problems of the health care system required “national solutions,” (2) the American health care system would work better if “workers and managers bargained with each other to decide on health benefits,” or (3) “each person ought to make the choices” about his or her own health care. The questions from the surveys focused more on allocations of responsibility, to either “the government in Washington” or individuals taking care of health issues on their own. Support for active employers was assessed from the surveys according to whether respondents endorsed a larger role for business in shaping “government health policies and programs.”

Finally, we can derive from the literature several ways in which physicians might be seen to be overstepping their appropriate scope of authority. First, some respondents felt that the allocation of health care resources ought to be controlled by communities. Support for this position was measured on the interviews by agreement that contemporary health problems could best be addressed by “local government or community-based groups.” On the surveys, this attitude was attributed to respondents who predicted that health care reforms delegating authority to community-based decision makers would benefit the country as a whole.

The second set of boundary violations pertains to the medical profession's political activities. Questions from the interviews and the surveys captured different aspects of these perceptions. Interview subjects were asked whether they thought that most Americans were “comfortable having physicians guide policymakers” with respect to health care reform. Those who disagreed could be expected to be less trusting of physicians’ political activities. Respondents to the surveys were asked whether they thought that physicians had exerted too much or too little influence over the health care reform debate between 1993 and 1994. Those who considered the profession's influence to have been excessive were more likely to be skeptical of medical authority in the political realm.

Clearly, some of these measures are better able than others to capture the core concepts in the hypotheses. Nonetheless, it is important to include in our statistical analyses even the less proximate measures. Even if these are not close proxies for the attitudes we would like to measure, as long as the measures are correlated with those attitudes, they ensure that our other estimated relationships are not biased because some conceptually important influences on perceptions of medical authority were omitted.

Other Explanatory Variables

To accurately measure the relationship between these attitudes and perceptions and the respondents’ support for medical authority, we had to control for other political predispositions and sociodemographic characteristics that might be associated with support for medical authority and otherwise were conflated with the relationships that we were trying to assess. Because a number of our measures of medical authority were linked to the ongoing debates over health care reform, it was important to measure political attitudes that might have been correlated with support for health care reform in general. Past studies documented that ideology influenced this assessment, with liberals consistently more supportive of health care reforms of all sorts than conservatives were (Schlesinger and Lee 1993). Both interviews and surveys contained questions in which respondents placed their own predispositions on a scale between liberal and conservative. Because health care reform during 1993–94 became so closely identified with the Clinton administration, it also took on a partisan veneer (Skocpol 1996). Both interviews and surveys also contained measures of party identification.

Some sociodemographic characteristics might predispose respondents to be more or less supportive of professional authority. Supporters of the women's health movement, for example, are the group most often identified as challenging physicians’ dominance (Weissman 1998). One might therefore expect women to be more skeptical of medical authority (Schlesinger and Heldman 2001). Past research suggests that patients from ethnic and racial minorities often report comparable problems with physician-patient communication and quality of care (Blendon, Aiken, Freeman, et al. 1989; Lieu, Newacheck, and McManus 1993; Smith 1998). This may also translate into less acceptance by minorities of physicians’ control over the health care system or health policy. Past research also suggests that younger and better-educated persons become more active consumers in their own medical care (Hibbard and Weeks 1987). These characteristics might therefore be associated with greater skepticism of medical authority generally. Both the interviews and surveys contained measures of sex, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, and age.

Analytic Methods

The measures capturing threats to medical authority are summarized in table 2. To assess the impact of these attitudes and perceptions on professional legitimacy, I estimated a set of regression models. The five measures of support for medical authority serve as the dependent variables in these models, with the variables measuring political predispositions and sociodemographic characteristics included as other explanatory variables to control for potentially spurious correlations. Because the dependent variables involved responses on four- or five-point scales, the regressions were estimated as both ordinary least squares (OLS) and ordered logistic regressions. The results were virtually identical with both specifications. Because it is easier to interpret the magnitude of the coefficients from the OLS models, these are presented here. Any differences from the ordered logistic specifications are noted in the text.

Because the public's political sophistication is expected to mediate the prevalence of attitudes related to medical authority, it was not appropriate to simply control for sophistication in the regression models. Instead, we examined the attitudes identified in the models as most closely associated with acceptance or rejection of medical authority and then explored the extent to which those attitudes varied according to sophistication. To do this, we needed some measures of political sophistication of the American public.

For both the interviews and the survey samples, I grouped the public respondents into categories of low, medium, and high political sophistication. For the interview subjects, I based this grouping on the extent to which they had followed the health-reform debate and felt informed about these issues. Those who indicated that they had both followed the debate and felt informed were labeled “high sophistication.” This group represented 24 percent of the public interview sample. Those who had neither followed the debate nor felt informed (also 24 percent of the public subjects) were identified as “low sophistication.” The remainder were categorized as “moderately sophisticated.” Survey respondents were categorized according to their ability to accurately answer a standard battery of questions about American politics (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996; Zaller 1992). The respondents were asked four questions: (1) Did they know what office Al Gore held? (2) Did they know what branch of government decided the constitutionality of laws? (3) Did they know which party controlled the House? and (4) Did they know which party was the most conservative? The public respondents on this survey had about the same level of current political knowledge as the country as a whole (as measured by the 1994 National Election Survey), although they appeared to know more about the Constitution. Those who answered all the questions correctly (30 percent of the sample) we treated as “high sophistication” respondents, and those who answered one or none of the questions correctly (45 percent of the sample) we labeled “low sophistication.”

Results

We first examined the prevalence of support for medical authority among the American public and policy elites. Then we (1) assessed the prevalence of threats to professional authority and (2) determined which of the threats was most closely related to lower levels of support for medical authority. Last we explored the mediating effects of political sophistication.

The Prevalence of Support for Medical Authority

The interviews and surveys measured five kinds of support for medical authority. Together, they provide a reasonably comprehensive assessment of attitudes toward physicians' influence over medical care and health policy. As is evident from table 3, in 1995 the general public's support for professional influence was modest at best. Slightly less than half of all Americans thought that physician-controlled health care reform would be good for the country. When this was compared with other reforms, only about one-third of all respondents endorsed professional control. Attitudes toward physicians’ influence over policymaking were even less positive. Only about one in five members of the public favored the medical dominance of policy development, and only about a quarter favored relying on the medical establishment to set the direction for new health policies.

TABLE 3.

Support for Medical Authority among the Public and Policy Elites, 1995

| Percentage Agreeing with the Statement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measures of Support | General Public | Political Elites |

| From the Interviews | ||

| The best solutions to problems of American medicine come from “relying on those who provide health services.” | 28.8 | 17.7 |

| “The health care system would work better if doctors had full control over the system.” | 18.5 | 2.0* |

| Medical care should be allocated by physician-run groups. | 47.9 | 22.5* |

| From the Surveys | ||

| Favors physician-run health care reform (compared with other alternatives). | 36.6 | 29.8* |

| Physician-controlled reform would be positive for the country as a whole. | 47.7 | 35.0* |

Difference between the public and elites was statistically significant at the 5 percent confidence level.

If public support for medical authority is lukewarm, the attitude among policy elites is downright chilly. Depending on the measure, a third or fewer of elites favored physician-controlled allocation of medical care. Elite respondents, moreover, expressed outright hostility toward physicians’ influence over policymaking. It was nearly impossible to find anyone in Washington who supported a strong role for physicians, or even a stronger role than they had in the 1993–94 health reform debate.

Note that the apparent level of support for professional authority differs significantly across these questions. Some of this variation can be attributed to differences in the questions’ wording or the categorization of response scales. But the most pronounced differences reflect the implicit extent of physician control. Just under half the public (between a quarter and a third of elites) endorsed reforms giving physicians some control over the allocation of medical resources (the third and fifth rows of table 3). However, the more extreme proposition giving physicians “full control” over the medical care system (the second row of table 3) was supported by less than 20 percent of the public and a scant 2 percent of political elites.

The Prevalence of Attitudes Threatening Medical Authority

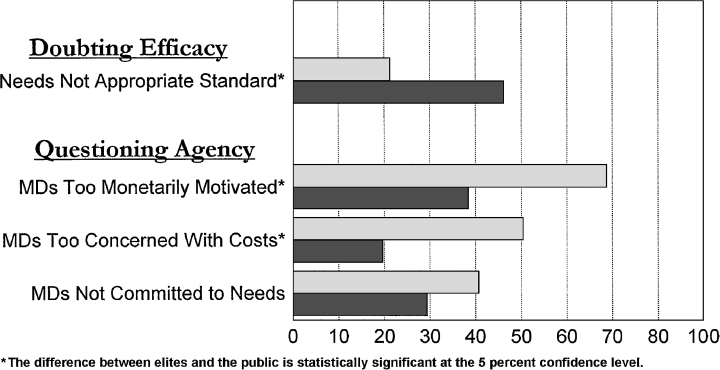

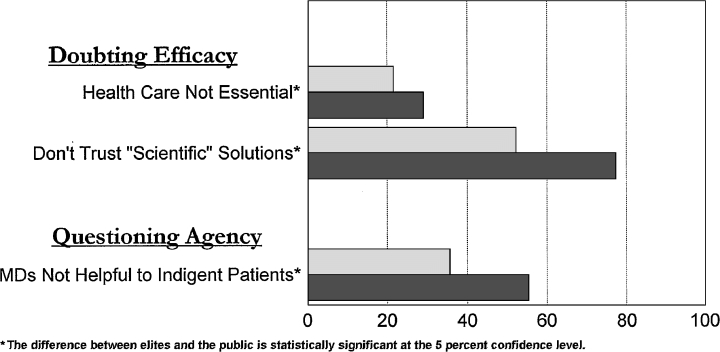

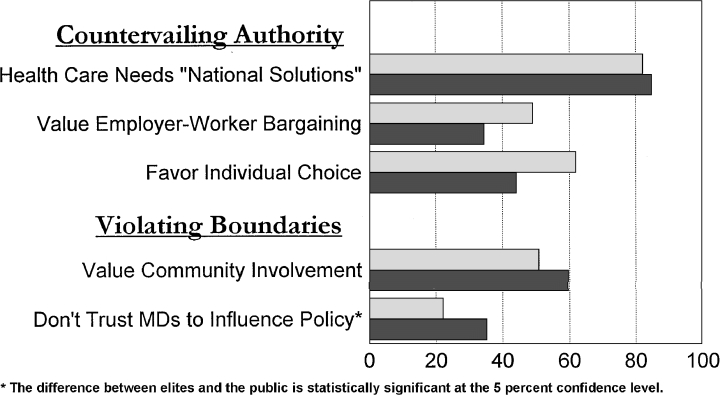

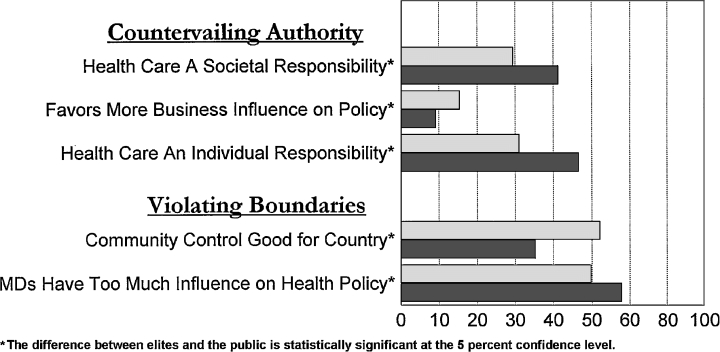

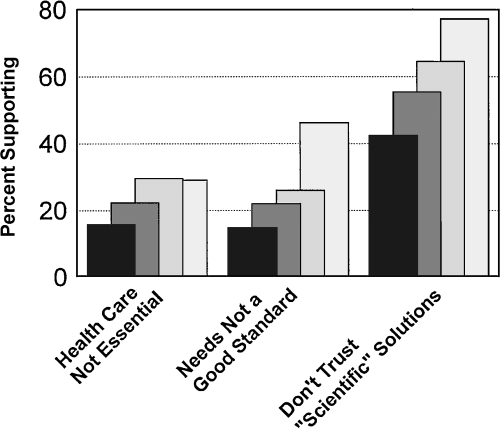

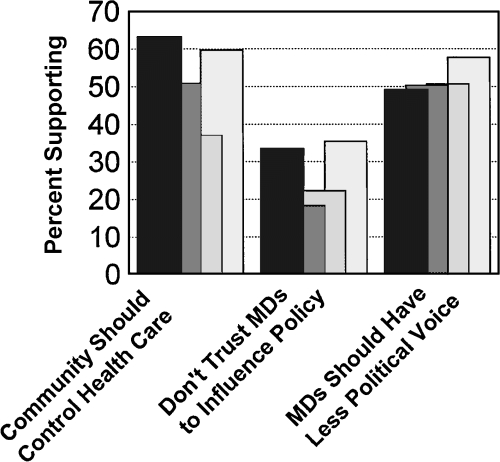

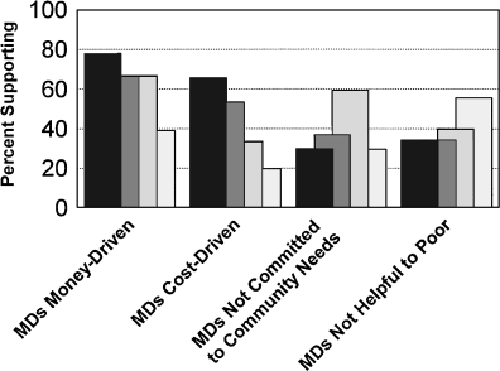

The attitudes expressed by public and elite respondents are reported in four of the figures. Measures related to efficacy and agency from the interviews are presented in figure 3, and measures from the surveys relevant to these hypotheses are presented in figure 5. Measures from the interviews related to countervailing authority and violations of professional boundaries are presented in figure 4, with the corresponding measures from the surveys presented in figure 6.

fig. 3.

Interview-based measures of the efficacy and agency of the medical profession. These attitudes were assessed using the levels of support for each of these statements reported by elite (█) and public (▒) subjects.

fig. 5.

Survey-based measures of the efficacy and agency of the medical profession. These attitudes were assessed using the levels of support for each of these statements reported by elite (█) and public (▒) respondents.

fig. 4.

Interview-based measures of countervailing authority and boundary violations. These attitudes were assessed using the levels of support for each of these statements reported by elite (█) and public (▒) subjects.

fig. 6.

Survey-based measures of countervailing authority and boundary violations. These attitudes were assessed using the levels of support for each of these statements reported by elite (█) and public (▒) respondents.

A number of patterns are apparent in these findings. Many of the attitudes considered threatening to medical authority were reasonably common in 1995. Both elite and public respondents supported a number of potential sources of countervailing authority. But other attitudinal domains showed some clear differences between the American public and political elites. On the one hand, the public appeared to be far more concerned about physicians who failed to act as reliable agents for patients (half saw patients’ needs as being subordinated to cost containment, and two-thirds were concerned about the extent of physicians’ self-interest in the health care system). Political elites, on the other hand, were more concerned about issues of efficacy (they were more than twice as likely to doubt the use of need as an appropriate standard for allocating medical services and much more likely to question the scientific basis of professional decisions), more aware of providers who failed in their roles as societal agents (more concerned about physicians’ unwillingness to care for the poor) and somewhat more likely to see physicians as exceeding their appropriate boundaries of political influence.

To what extent might these attitudes and perceptions account for the reduced acceptance of physicians’ authority over the health care system? The relationship between these attitudes and our measures of acceptance of medical authority is presented in table 4 (for the regressions based on data from the interviews) and table 5 (for the regressions based on data from the surveys of the public and congressional staff).

TABLE 4.

Interviewees’ Attitudes Shaping Support for Medical Authority

| Dependent Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Should Rely on Physicians for Policy Answers | Physicians Should Control Resources | Favors Physician-Run, Group Health Plans | ||||

| Explanatory Variables* | Coef. | Sig. | Coef. | Sig. | Coef. | Sig. |

| Doubts about Efficacy | ||||||

| Need is not an appropriate standard for health care. | −0.024 | NS | −0.171 | 0.02 | −0.171 | 0.02 |

| Questions about Agency | ||||||

| Physicians are too monetarily oriented. | −0.212 | 0.01 | −0.093 | NS | 0.127 | NS |

| Physicians are too concerned about medical costs. | 0.060 | NS | 0.050 | NS | 0.125 | NS |

| Needs are not treated as the foremost concern. | −0.008 | NS | −0.117 | NS | −0.92 | NS |

| Support for Countervailing Authority | ||||||

| Favors national solutions to health problems. | 0.072 | NS | 0.038 | NS | −0.153 | 0.05 |

| Values employer-based health decisions. | 0.050 | NS | 0.138 | NS | 0.070 | NS |

| Supports active role for medical consumers. | 0.229 | 0.01 | 0.063 | NS | 0.052 | NS |

| Concerns about Violation of Boundaries | ||||||

| Values community participation in medical care. | 0.124 | NS | 0.058 | NS | −0.077 | NS |

| Physicians are not trusted to make good policy choices. | −0.323 | 0.01 | −0.287 | 0.01 | −0.286 | 0.01 |

| Overall Regression Statistics | ||||||

| R-squared | 0.357 | 0.343 | 0.297 | |||

| Number of observations | 148 | 148 | 148 | |||

Regression models also include variables measuring ideology, party affiliation, education, sex, race, ethnicity, and age.

TABLE 5.

Survey Respondents’ Attitudes Shaping Support for Medical Authority

| Dependent Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supports Physician-Controlled Reforms | Physicians’ Control is Good for the Country | |||

| Explanatory Variables* | Coef. | Sig. | Coef. | Sig. |

| Doubts about Efficacy | ||||

| Medical care is not needed for equal opportunity. | −0.61 | 0.03 | −0.122 | 0.01 |

| Allocating services based on “scientific” answers may not be wise. | −0.187 | 0.01 | −0.202 | 0.01 |

| Questions about Agency | ||||

| Physician-controlled reforms will hurt the poor. | −0.159 | 0.01 | −0.368 | 0.01 |

| Support for Countervailing Authority | ||||

| Supports societal responsibility for medical care. | 0.086 | NS | −0.009 | NS |

| Favors more business influence over health policy. | −0.015 | NS | −0.044 | NS |

| Supports individual responsibility for medical care. | −0.100 | NS | −0.242 | 0.01 |

| Concerns about Violation of Boundaries | ||||

| Favors community control over medical care. | −0.021 | NS | −0.067 | 0.01 |

| Physicians have too much influence over policymaking. | −0.30 | NS | 0.025 | NS |

| Overall Regression Statistics | ||||

| R-squared | 0.129 | 0.267 | ||

| Number of observations | 1,415 | 1,413 | ||

Regression models also include variables measuring ideology, party affiliation, education, sex, race, ethnicity, and age.

The Relationship between Attitudes and the Acceptance of Medical Authority