Abstract

Recent research indicates declining age-adjusted chronic disability among older Americans, which might moderate health care costs in the coming decades. This study examines the trend’s underlying components using data from the 1984–1999 National Long-Term Care Surveys to better understand the reasons for the declines and potential implications for acute and long-term care. The reductions occurred primarily for activities like financial management and shopping. Assistance with personal care activities associated with greater frailty fell less, and independence with assistive devices rose. Institutional residence was stable. More needs to be known about the extent to which these declines reflect environmental improvements allowing greater independence at any level of health, rather than improvements in health, before concluding that the declines will mean lower costs.

Since the mid-1980s, researchers and policymakers have been concerned that increased longevity and the aging of the baby boom generation will result in not only a larger elderly population but also a higher prevalence of disability. Greater longevity could mean more years of disability and higher long-term care and other medical costs if medical interventions are able to prolong life but not health and independence. But if the aging of the population is accompanied by sufficiently large improvements in health and independence among the elderly, the impact of aging on costs may be moderated.

Recent findings using several different data sources have provided evidence of improvements in elderly people’s physical functioning. Studies examining the age-adjusted prevalence of disability among the elderly have found declines in recent years (Manton and Gu 2001; Waidmann and Liu 2000; Waidmann and Manton 1998). Other studies have found an increase in disability-free life expectancy (Crimmins, Saito, and Ingegneri 1997) and a decrease in physical limitations—such as lifting ten pounds, walking short distances, and climbing a flight of stairs—that are related to the onset of disability (Freedman and Martin 1998).

These potentially encouraging findings are tempered, however, by other findings that some aspects of disability show reductions but not a consistent downward trend and that these reductions have been concentrated at lower levels of disability (Schoeni, Freedman, and Wallace 2001; Waidmann and Liu 2000). For example, Schoeni and colleagues found that among the noninstitutionalized population aged 70 and older, the disability rate fell between 1982 and 1986 but fluctuated between 1986 and 1996, ending the period essentially unchanged. Other studies found increases in the use of formal long-term care services (Liu, Manton, and Aragon 2000; Spillman and Pezzin 2000) and the level of disability among those receiving help with chronic disabilities, including residents of institutions (Rhoades and Krauss 1999; Sahyoun et al. 2001; Spillman and Pezzin 2000). These findings could suggest higher average long-term care costs among the disabled, which could offset savings due to a declining prevalence of disabilities.

Clearly, we need a better understanding of the underlying structure of changes in the prevalence of disability in order to estimate the likely short- and long-term cost implications of a reduction in disability and to predict how disability rates are likely to change through midcentury as the population continues to age. This study takes a first step by using data from four waves of the National Long-Term Care Survey to decompose the trends and examine which aspects of disability have declined and the potential implications for service use and costs.

The following questions are addressed:

How has the prevalence of chronic disability among the elderly changed since the mid-1980s?

Does the trend in the prevalence of disability differ for specific components, such as disability only in basic activities necessary for independent living or disability managed solely by the use of equipment?

Are trends different for younger ages and older cohorts?

Are there particular activities for which disability declines are larger or which appear to be more amenable to independence with the use of special equipment or to changes in environmental or social factors?

What are the implications for future costs?

Data and Methods

This analysis uses data from the 1984, 1989, 1994, and 1999 waves of the National Long-Term Care Survey (NLTCS), conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau under the direction of the Center for Demographic Studies at Duke University. The NLTCS is a nationally representative survey of persons aged 65 and older designed to identify those who are chronically disabled, as defined by activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and to collect detailed data on their disability, service use, family support, and health and demographic characteristics. The samples were drawn from Medicare enrollment files and include both community and institutional residents. For the NLTCS, institutional residents are defined as those living in nursing homes as well as those who live in other group settings with medical supervision, such as mental facilities and residential care homes. The longitudinal component of the survey is refreshed in each wave with a new sample of persons who turned 65 since the previous survey, and in 1994 and 1999, a supplemental sample of those aged 95 or older was added to increase the precision of estimates for the very old. There were about 21,000 respondents in 1984, 16,000 in 1989, and 17,000 in 1994 and 1999. Although the survey began in 1982, the 1984 survey is the base year for this analysis because it was the first wave in which detailed information about the disabled in institutional settings also was collected. Proxy interviews were conducted for all the institutional residents and for those community residents who were unable to respond for themselves because they were too frail or were cognitively impaired. The rate of proxy response generally has dropped, from about 23 percent of the elderly in 1984 to about 18 percent in 1999.

Although the NLTCS is a complex survey, its complexity represents a strength for the detailed examination of disability patterns. The survey uses a very broad definition of disability to screen the full population and to determine whether an individual will receive a detailed interview. The screening interview identifies those who have a “problem” performing any of six ADLs without help or equipment, who are incontinent, who have difficulty going outside without help or equipment, or who are unable to perform any of seven IADLs without help because of a health or disability problem. Those who report no chronic problems requiring help or equipment in the screening interview “screen out” as not disabled and, with the exception noted later, do not receive a detailed interview. To be eligible for a detailed interview—to “screen in”—the subject must have had or expect to have at least one of the problems or inabilities for three months or more. Those who are in an institution or who received a detailed interview in a previous survey year are automatically interviewed without a new disability screen. In 1994 and 1999, samples of “healthy” persons who reported no problems or inabilities in their screening interview also received a detailed interview, excluding the detailed disability questions, since they already had reported no problems or inabilities in ADLs or IADLs. The total number of detailed interview respondents was about 7,600 in 1984 and about 6,000 in the other years.

Disability Measures

This analysis defines a person with a chronic disability as one receiving help or using equipment to perform at least one ADL or being unable to perform at least one IADL without help for at least three months, as reported in the detailed interview. ADLs are basic activities necessary for personal care and generally are an indicator of a greater level of disability or frailty than IADLs, which are activities more closely related to the ability to live independently. The ADLs included in this analysis are eating, getting in and out of bed (transfer), getting around inside (indoor mobility), toileting, bathing, and dressing. The IADLs are doing light housework, doing laundry, preparing meals, shopping for groceries, getting around outside, taking medications, managing money, and using the telephone. Going beyond walking distance (transportation) is not included as an IADL in this analysis. Whereas the screening interview asks about having a problem or difficulty with ADLs, the detailed interview focuses on whether the respondent receives active human help or supervision with each activity or uses equipment to perform the activity. With one exception, the IADL questions in the detailed interview relate only to the person’s ability to perform the activity without help. The exception is getting around outside, for which the respondents may report using equipment without human help or supervision. The small group for whom this was the only reported disability is included in the chronic disability estimates but is reported separately.

Distinguishing Long-Term Care

An important concern of this study is the implications of disability trends for the cost of long-term care, which is the receipt of help, including supervision. Therefore, disability measures distinguish between those persons receiving human help for at least three months—implying use of paid or unpaid services—and those persons who received no help but used disability-related equipment for at least three months. For each ADL or IADL, measures identify the respondents as receiving help if they reported receiving help, regardless of whether they also used equipment with the activity. Respondents were identified as using equipment for an activity only if they reported equipment use but no human help. The disability classification used in the tables combines the individual disabilities hierarchically to distinguish those receiving long-term care and those who were independent but used equipment, as follows: Community residents who reported receiving help with any of the six ADL activities for at least three months were classified as receiving human help with ADLs. The remaining respondents who were community residents were classified as receiving human help with IADLs if they reported needing help with any of the eight activities for at least three months. All the institutional residents receive human help, by definition. The remaining group who reported not needing human help with any activity for as long as three months was classified as using equipment with ADLs if they reported using equipment for any ADL for at least three months. The small number of people whose only reported chronic disability was having to use equipment to get around outside was classified as IADL equipment only. Respondents classified as receiving help with any activity may also use equipment for that or other activities, but they are only classified as “equipment only” if they do not regularly receive help with any activity. The remainder of the analysis sample, who reported neither regularly receiving help nor using equipment for at least three months, was classified as not chronically disabled. Individuals in each disability category also may have reported receiving human help or using equipment for activities that did not meet the three-month criterion for chronic care.

Weights and Estimation

Estimates must be weighted in each year to account for the complex survey design. However, the poststratification methodology used to create the weights released with the surveys changed between 1984 and 1989 and again between 1994 and 1999. Because of this change in methodology, the estimates for 1984 and 1999 are not comparable to estimates for the two intervening years if the weights released with the survey are used. (See the discussion of the 1989 and 1994 second-stage factors in Center for Demographic Studies 1989, 1996, 2001 and the discussion of the 1999 survey weights in CDS 2003.) Therefore, to allow comparisons over time, for this study, substitute weights were created for 1984 and 1999 that follow the methodology used in creating the 1989 and 1994 survey weights. Population estimates for the substitute weights were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. The primary result is a smaller estimate of the institutional population in 1984 and a larger estimate in 1999 than the NLTCS estimates published elsewhere (Federal Interagency Task Force on Aging-Related Statistics 2000; Manton and Gu 2001). The weight released with the 1999 survey was of particular concern because, unlike the weights in previous rounds, the cell counts for the institutional sample were not poststratified to counts from an external control total (Center for Demographic Studies 2001, 2003). This methodology generated an estimate of 1.47 million institutional residents, of whom 1.2 million were in nursing homes (Manton and Gu 2001). This nursing home estimate, however, was very low compared with the 2000 census estimate of 1.56 million elderly nursing home residents (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2001) and with the 1.47 million estimate from the 1999 National Nursing Home Survey (National Center for Health Statistics 2002). The substitute 1999 weight created for the current study yields an estimate of 1.42 million nursing home residents out of a total of 1.66 million institutional residents.

This methodological difference is important to keep in mind because it reduces the magnitude of the decline in disability found in this study. Details of the rationale and weighting strategy are provided in the appendix. Unless otherwise noted, the estimates discussed are significant at the 5 percent level of significance in a two-tailed test.

The Trend in the Prevalence of Disability

There is a clear downward trend in the percentage of the elderly population who are chronically disabled (Table 1). In 1984, 22.1 percent of the elderly population reported having a chronic disability, but by 1999 this percentage had fallen to 19.7, an average drop of 0.16 percentage points (0.8 percent) per year over the 15-year period. The largest decrease (0.24 percentage points, or 1.17 percent) was between 1989 and 1994, consistent with the finding by Manton, Corder, and Stallard (1997) that the decline in disability accelerated between 1989 and 1994. The 0.4 percentage point drop between 1994 and 1999 was not statistically significant. This finding differs from Manton and Gu’s (2001), who reported that the rate of decline continued to accelerate between 1994 and 1999. The disparity results from the difference in weighting methodologies in 1999.

TABLE 1.

Percent of Elderly Population Meeting NLTCS Chronic Disability Criteria, 1984–1999

| Year | 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |

| Number of elderly (000s) | 27,968 | 30,871 | 33,125 | 34,459 | 2,903 | 2,254 | 1,334 | 5,157 | 3,588 | 6,491 |

| Distribution | Percentage | Percentage | Percentage | Percentage | ||||||

| No disability1 | 73.0 | 73.0 | 73.1 | 74.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.6* | 0.1 | 1.7* | 1.7* |

| Evidence of chronic disability but not now chronically disabled2 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 0.8* | 1.1* | −1.2* | 2.0* | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| Chronically disabled3 | 22.1 | 21.3 | 20.1 | 19.7 | −0.7 | −1.2* | −0.4 | −2.0* | −1.6* | −2.4* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 0.5* | 0.4* | 0.5* | 0.9* | 0.9* | 1.4* |

| Any human help | 19.8 | 18.5 | 16.9 | 15.9 | −1.3* | −1.6* | −0.9 | −2.9* | −2.5* | −3.8* |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 7.4 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.2 | −2.0* | −0.6* | −0.5 | −2.7* | −1.1* | −3.1* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL activity | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.8* | −0.5 |

| Institutional resident | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 0.4 | −0.3 | −0.3 | 0.1 | −0.6* | −0.2 |

Note: Estimates may not add up to column or row totals because of rounding.

*Difference is statistically significant at the 5% level in a two-tailed test.

Defined as being a community resident and 1) having no problem requiring human help or special equipment with any of six ADLs (eating, transfer, indoor mobility, dressing, bathing, and toileting), incontinence, or outside mobility, and 2) being able to perform all of eight IADLs (preparing meals, doing laundry, doing light housework, shopping for groceries, getting around outside, managing money, taking medicine, and making phone calls).

This group includes those who reported difficulty with ADLs or inability to perform IADLs on the screening interview or were disabled in a previous round of the survey but either failed to meet the three-month criterion for chronic disability or reported no ADL or IADL disability on the detailed interview.

Persons who are chronically disabled comprise those performing IADLs with only equipment, those performing ADLs with only equipment, and those receiving human help to perform these activities. Persons receiving human help include community residents receiving help only with IADLs, community residents receiving help with ADLs, and institutional residents.

Through 1994, a constant 73 percent of the elderly population reported being free of chronic difficulty or disability in any ADL or IADL. In 1999, this percentage rose to 74.7. In each year, another 5 to 7 percent of the elderly population had reported a difficulty or disability in the current or an earlier round of the survey but did not meet the detailed questionnaire definition of chronically disabled in the current round. This group differs from those reporting no difficulty or disability, in that they have provided some evidence of current or earlier difficulties and may be in poorer health and at a higher risk of future chronic disability, even though they are not currently chronically disabled. There was no trend in the size of this group, which is not included in the estimates of chronic disability.

Underlying the downward trend in aggregate disability is a pattern of steadily increasing equipment use and declining human help with disabilities. The use of equipment for ADLs with no human assistance rose 1.4 percentage points (from 1.6 percent to 3.0 percent) over the 15-year period. Conversely, the prevalence of receiving human help with any disability fell from 19.8 percent in 1984 to 15.9 percent in 1999. This is an average decline of 0.26 percentage points, or 1.4 percent per year, again with a slightly larger average annual decline (0.32 percentage points, or 1.8 percent) between 1989 and 1994.

The decreasing rate of IADL-only disability accounts for most of the decline in receipt of human assistance. The percentage of persons receiving help only with IADLs in the community fell 3.2 percentage points over the 15-year period, from 7.4 percent in 1984 to 4.2 percent in 1999. Most of the decrease occurred between 1984 and 1989, with much smaller declines thereafter. In contrast, the combined prevalence of receiving help with ADLs or living in an institutional residence, which are associated with a higher level of disability or frailty, actually rose between 1984 and 1989 and began to fall from the 1984 level only after 1994. Although the 0.2 percentage point decline in the prevalence of persons receiving help with ADLs in the community between 1994 and 1999 is not significant, the 0.8 percentage point decline from the peak in 1989 is significant and implies an average annual decline of slightly less than 0.1 percentage point, or 1.1 percent, between 1989 and 1999.

Community and Institutional Residence

The reduction in the disability rate does not appear to have resulted in a lower prevalence of institutional residence, contrary to what might be expected if the reduction resulted solely from improved health among the elderly. With the exception of a small increase in the prevalence of institutional residence between 1984 and 1989, the trend has been relatively flat at about 5 percent of the elderly population, ending the period at 4.8 percent of the elderly population. (The prevalence estimate for 1999 is higher than the 4.2 percent of the elderly population residing in institutions reported in Manton and Gu [2001] and results from differences in the weighting methodology noted earlier and discussed in detail in the appendix.) Besides the implication that some aspects of disability may not be improving, the persistence of institutional residence—the most expensive type of long-term care—suggests that the decline in disability may not translate into a similar decline in costs.

The essentially constant prevalence of residence in institutions, where about 95 percent of residents receive assistance with ADLs, bolsters the apparent concentration of declines at lower levels of disability, as indicated by the dominant reduction in the IADL disability rate. The percentage of the elderly who were both disabled and residing in the community fell by an average of 0.2 percentage points annually in each of the first two five-year periods, from 17 percent in 1984 to 15 percent in 1994. This was primarily due to the large drop in IADL-only disability, partially offset by the rising number of persons using equipment for ADLs, but no human help. The decrease in rate of IADL disability accounts for more than 80 percent of the overall 3.8 percent decline in human assistance over the 15-year period.

Age and Chronic Disability

The results seen in the previous tables are consistent with underlying declines in age-specific disability rates, but growth since 1984 in the elderly population and in the proportion who are very old has partially offset the age-specific declines. In fact, despite the drop in the disability rate, the number of chronically disabled elderly grew from about 6.2 million in 1984 to about 6.8 million in 1999 (not shown). The top panel of Table 2 shows the age-specific prevalence of chronic disability for those aged 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and 85 or older. A downward trend in overall disability is evident for every age group, with the largest absolute declines in the two older age groups. This is not surprising because the prevalence of disability is far lower among the young elderly. Only 12.2 percent of those aged 65 to 74 in 1984 and 9.2 percent in 1999 were chronically disabled, less than one-fifth the rates for those aged 85 or older. In percentage terms, however, the declines were smallest for those aged 85 or older. The overall rate of disability fell less than 1 percent per year for the oldest group, compared with 1.5 to 2 percent per year for the two younger groups.

TABLE 2.

Percentage of Persons with Chronic Disability by Age Group, 1984–1999

| Percent of Age Group | 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |

| 65–74 | ||||||||||

| Any chronic disability | 12.2 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 9.2 | −1.4* | −0.5 | −1.2* | −1.8* | −1.7* | −3.1* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.5* | −0.4 | 0.8* | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Any human help | 10.6 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.2 | −1.7* | −0.9 | −0.8 | −2.6* | −1.8* | −3.4* |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 4.4 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.5 | −1.6* | −0.2 | −0.2 | −1.7* | −0.4 | −1.9* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.6 | −0.9* | −1.1* |

| Institutional resident | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.4* | −0.4* |

| 75–84 | ||||||||||

| Any chronic disability | 29.1 | 27.6 | 24.3 | 23.4 | −1.4 | −3.3* | −0.9 | −4.8* | −4.3* | −5.7* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.3 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.2* | 1.0* | 1.7* | 2.2* |

| Percent of Age Group | 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |

| Any human help | 25.7 | 23.7 | 20.0 | 18.0 | −2.0* | −3.7* | −2.0* | −5.7* | −5.7* | −7.7* |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 10.3 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 5.0 | −2.7* | −1.6* | −1.0* | −4.3* | −2.6* | −5.3* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL | 9.0 | 9.7 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 0.7 | −1.2* | −0.5 | −0.5 | −1.7* | −1.0 |

| Institutional resident | 6.4 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 0.1 | −0.9 | −0.5 | −0.8 | −1.4* | −1.3* |

| 85 and older | ||||||||||

| Any chronic disability | 62.0 | 61.7 | 57.3 | 55.5 | −0.3 | −4.4* | −1.8 | −4.7* | −6.2* | −6.5* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 1.9 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 5.7 | 1.9* | −0.4 | 2.4* | 1.4* | 1.9* | 3.8* |

| Any human help | 59.0 | 56.7 | 52.7 | 48.4 | −2.3 | −4.0* | −4.3* | −6.3* | −8.3* | −10.6* |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 16.6 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 9.8 | −4.1* | −1.5 | −1.3 | −5.5* | −2.7* | −6.8* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL | 19.9 | 19.7 | 18.4 | 18.5 | −0.2 | −1.4 | 0.1 | −1.5 | −1.2 | −1.4 |

| Institutional resident | 22.5 | 24.5 | 23.3 | 20.1 | 2.0 | −1.2 | −3.2* | 0.8 | −4.4* | −2.4 |

| Percent of Age Group | 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |

| 65–74 | ||||||||||

| Any chronic disability | 7.3 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 4.8 | −1.1* | −0.4 | −1.0* | −1.5* | −1.4* | −2.5* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.3* | −0.3* | 0.4* | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Any human help | 6.4 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 3.8 | −1.2* | −0.7* | −0.7* | −1.9* | −1.4* | −2.6* |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | −1.0* | −0.1 | −0.2 | −1.1* | −0.3* | −1.3* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.9 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.4* | −0.5* | −0.7* | −0.9* |

| Institutional resident | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.2* | −0.3* | −0.3* |

| 75–84 | ||||||||||

| Any chronic disability | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 0.0 | −1.0* | 0.2 | −1.0* | −0.8* | −0.8* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5* | 0.4* | 0.7* | 0.9* |

| Percent of Age Group | 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |

| Any human help | 7.9 | 7.7 | 6.6 | 6.3 | −0.2 | −1.1* | −0.3 | −1.3* | −1.4* | −1.6* |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 | −0.7* | −0.5* | −0.2 | −1.2* | −0.7* | −1.4* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.4 | −0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.0 |

| Institutional resident | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.1 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.2 |

| 85 and older | ||||||||||

| Any chronic disability | 5.8 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9* |

| Community IADL equipment only | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Community ADL equipment only | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.2* | 0.0 | 0.3* | 0.2* | 0.3* | 0.5* |

| Any human help | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Community human help with IADLs only | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | −0.3* | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.3* | −0.1 | −0.4* |

| Community human help with at least one ADL | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4* |

| Institutional resident | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.5* | 0.0 | 0.3 |

Note: Estimates may not add up to column or row totals because of rounding.

Difference is statistically significant at the 5% level in a two-tailed test.

The composition of declines is somewhat more mixed within the age groups. For example, between 1994 and 1999 the youngest age group had a small though insignificant decline in independence using equipment, resulting in no net change over the 15-year period, whereas the largest increases for the two older groups occurred between 1994 and 1999. As seen earlier for the elderly as a whole, the age-specific prevalence of persons receiving help only for IADLs was roughly halved over the 15-year period and was the dominant factor in the overall drop in human assistance. For all groups, the largest improvement in IADL help occurred between 1984 and 1989. In fact, the youngest age group had a significant decrease only between 1984 and 1989, with no significant decline between 1989 and 1999. The within-age-group prevalence of persons receiving human help with ADLs and institutional residence fell far less. Although the declines appear to be larger for the oldest group, the change over the 15-year period was not significant for those aged 85 or older. As for the elderly as a whole, significant declines in the prevalence of persons receiving ADL help in the community or living in institutions came only after 1989 for all age groups.

The age-specific decreases in disability were moderated by the upward shift in the age distribution of the elderly population over the 15-year period (Table 2, lower panel). Persons aged 65 to 74 were 60 percent of the elderly population in 1984 but only 53 percent in 1999, whereas those aged 85 or older increased from about 9 percent to 12 percent of the elderly population (not shown). Chronically disabled persons in the two younger age groups represent declining proportions of the elderly population over the 15-year period, but the disabled aged 85 or older actually make up a slightly larger proportion of the elderly because of the combined impact of growth in the size of this age group and their far higher disability rate relative to that of the younger groups. This demonstrates how the rising age of the population can lessen the impact of disability declines on observed cross-sectional prevalence rates. In fact, through 1994, the increase of 0.7 percentage points in the proportion of the elderly aged 85 or older and receiving human help with ADLs or institutionalized was sufficient to overcome a similar decline for the youngest age group. The result was the essentially flat number of persons receiving ADL help or living in institutions between 1984 and 1994 seen earlier.

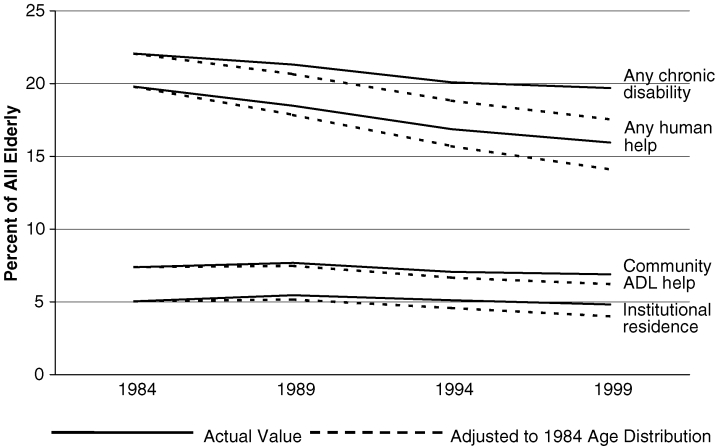

Figure 1 illustrates the tradeoff between the declining age-specific prevalence of disability and the aging of the elderly population over the 15-year period. The solid line shows the actual percentage of the elderly population with any sort of chronic disability, any human help, ADLs with help in the community, and living in institutions; and the dashed lines show what these percentages would have been if the age distribution among the elderly had not changed since 1984. Clearly, all the actual trends are flatter than their age-standardized counterparts. The 1.5 percent annual rate of decline in the age-standardized trend for aggregate chronic disability is nearly twice the 0.8 percent that actually occurred (Table 3). This same moderating impact of aging is evident for the components of disability most associated with greater frailty. The actual prevalence of persons receiving ADL help in the community, which began to drop only after the peak in 1989, fell at a rate of 0.5 percent per year, whereas the standardized trend shows a drop of 1.1 percent per year. Similarly, the actual percentage of institutional residents fell 0.3 percent per year, compared with 1.5 percent per year for the standardized trend. Interestingly, both IADL disability and independence in ADLs with equipment are fairly insensitive to upward shifts in the age distribution. The actual upward trend in equipment use was slightly greater than the age-standardized trend.

Figure 1.

Actual and Age-Standardized Chronic Disability

TABLE 3.

Actual and Age-Standardized Annual Percentage Rates of Change in Components of Chronic Disability

| Age-Standardized (1984 Age Distribution) | Actual Trend | |

|---|---|---|

| Any disability | −1.5% | −0.8% |

| Community ADL equipment | 3.9% | 4.4% |

| Any human help | −2.2% | −1.4% |

| Community help IADLs only | −4.2% | −3.6% |

| Community help ADLs | −1.1% | −0.5% |

| Institutional resident | −1.5% | −0.3% |

Trends in Individual Activities

Given that the trends for underlying components of disability differ from the overall downward trend in chronic disability, it is reasonable to ask whether the trends for individual activities also differ and can provide insights into potential reasons for the decline in disability. A central unanswered question is whether declines indicate improvements in health or environmental changes that promote greater independence for any given level of frailty. Table 4 examines the trends over the 15-year period for individual IADL disabilities, ADL disabilities managed with equipment only, and ADLs with human help that underlie the overall trend in disability. It is clear that just as the overall trend in disability is driven by declines in help with only IADLs, nearly all the declines in the prevalence of persons receiving help with individual disabilities were for these activities, with almost no change in the prevalence of individual ADL items.

TABLE 4.

Percent of Elderly Population Reporting Individual IADL and ADL Disabilities, 1984–1999

| 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |

| Community IADL help | ||||||||||

| Grocery shopping | 10.9 | 9.9 | 8.8 | 7.2 | −1.0* | −1.0* | −1.6* | −2.1* | −2.7* | −3.7* |

| Managing money | 8.4 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 3.9 | −3.7* | −0.3 | −0.5* | −4.0* | −0.8* | −4.5* |

| Doing laundry | 7.9 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 5.3 | −0.8* | −0.8* | −1.0* | −1.6* | −1.8* | −2.6* |

| Outdoor mobility | 7.1 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.8 | −0.5 | −0.4 | 0.5 | −0.9* | 0.1 | −0.4 |

| Preparing meals | 5.6 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.3 | −0.4 | −0.2 | −0.6* | −0.7* | −0.9* | −1.3* |

| Taking medication | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 0.2 | −0.5 | 0.4 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 0.2 |

| Light housework | 4.8 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.1 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −0.5* | −0.3 | −0.7* |

| Using the telephone | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.2 | −0.4 | −0.6* | −0.1 | −0.9* | −0.7* | −1.0* |

| Community ADLs with equipment only | ||||||||||

| Getting around inside | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.3 | −0.2 | 0.1 |

| Bathing | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 0.4* | 0.0 | 0.8* | 0.4* | 0.9* | 1.3* |

| Getting in and out of bed | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 0.3 | −0.2 | 0.7* | 0.1 | 0.5* | 0.8* |

| Toileting | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.6* | 0.5* | −0.2 | 1.2* | 0.4* | 1.0* |

| Dressing | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Eating | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Community ADLs with human help | ||||||||||

| Bathing | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 0.1 | −0.3 | −0.4 | −0.2 | −0.7* | −0.6* |

| Dressing | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.0 | −0.4 | 0.1 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.3 |

| Getting around inside | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 0.2 | −0.3 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 |

| Getting in and out of bed | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.5* | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Toileting | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Eating | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 5-Year Change | 10-Year Change | 15-Year Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984–1989 | 1989–1994 | 1994–1999 | 1984–1994 | 1989–1999 | 1984–1999 | |||||

| Institutional ADLs with equipment only | ||||||||||

| Getting around inside | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.5* | −0.5* | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.6* | −0.1 |

| Toileting1 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.3 | 0.3 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Getting in and out of bed | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.2* | 0.1 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| Bathing | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Eating | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Dressing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Institutional ADLs with human help | ||||||||||

| Bathing | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 0.5* | −0.4 | −0.2 | 0.1 | −0.7* | −0.1 |

| Dressing | 3.6 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 0.6* | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4* | −0.1 | 0.5* |

| Getting in and out of bed | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 0.4* | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.4* | −0.1 | 0.3 |

| Toileting | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 0.4* | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4* | −0.1 | 0.4* |

| Getting around inside | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Eating | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.3 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 |

Note: Estimates may not add up to column or row totals because of rounding.

Difference is statistically significant at the 5% level in a two-tailed test.

Independence in toileting with equipment cannot be ascertained for institutional residents in 1984 and 1989 due to a skip logic error. Those who did not receive help with toileting were not asked about equipment in those years.

Because the NLTCS did not collect information on IADLs for the 5 percent of the elderly who were in institutions, all persons reporting disability in individual IADLs are community residents. Therefore, for each IADL item, the disability prevalence may be understated by as much as 5 percentage points. In all cases, the activities are ordered by prevalence in 1984 from highest to lowest. Those persons categorized in the previous tables as receiving help with at least one IADL or ADL may have other ADLs that they manage with equipment. For this reason, the prevalence of independence with equipment for some ADLs in Table 4, notably the use of equipment for getting around inside, exceeds the percentage in Table 1 of elderly persons who use ADL equipment but receive no human help with any activity. For each ADL reported in Table 4, however, individuals were categorized as either using help or using equipment without help. Thus, the sum of the percentage using ADL equipment and the percentage using ADL help for each activity equals the total prevalence of persons with a disability in that activity.

IADL Disabilities

Except for getting around outdoors and taking medication, the prevalence of all IADL disabilities showed a downward trend, but the most striking declines were in managing money, shopping for groceries, and doing laundry. The first two activities—managing money and grocery shopping—may reflect the increasing range of services and accommodations generally available in the economy during this period, such as telephone and electronic banking and shopping. The pattern for shopping is consistent with such a phenomenon, with steady, one percentage point declines in the first two periods and a much larger decline between 1994 and 1999. But nearly the entire 4.5 percentage point decline in help with money management occurred between 1984 and 1989, with far smaller declines in the subsequent five-year periods.

The precipitous drop in help with money management may reflect a change in the way Social Security makes payments more than it reflects an improvement in cognitive or physical health. In 1987 the Social Security Administration (SSA) adopted direct deposit as the default method of making payments, which represent at least half of income for two-thirds of the elderly (Social Security Administration 2000). Although in 1988 the SSA changed its policy to offer beneficiaries payment by either check or direct deposit, it continued to encourage direct deposit, and currently about 80 percent of SSA benefits are paid in this way (personal communication from Larry DeWitt, SSA historian). This change almost certainly contributed to the pattern for money management, which may suggest that some of those persons reporting difficulty in managing money, which is usually associated with cognitive difficulties (Spector and Fleishman 1998), were actually reporting a physical difficulty with getting out to cash or deposit checks. It is also possible that direct deposit encouraged the greater use of banks and bank-based money management services, including the automatic payment of bills.

Neither of these possibilities necessarily implies that the drop in reported inability to manage money is due to an improvement in the health or cognitive functioning of the elderly. Using the 1993 Assets and Health of the Oldest Old and the 1998 Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), Freedman, Aykan, and Martin (2001) found a decline in the proportion of persons aged 70 or older who were cognitively impaired and speculated that the improvement in cognitive functioning may have contributed to the decline in IADL disability observed in other data sources. A more recent study, which added the 2000 HRS and used a different methodology, did not find an improvement but noted the difficulty of measuring cognitive function and the sensitivity of results to methodological decisions (Rodgers, Ofstedal, and Herzog 2003). The trend in the population prevalence of cognitive impairment cannot be investigated directly using the NLTCS survey data because cognitive functioning was not assessed for the full population in the NLTCS before 1994. Furthermore, the assessment instrument was changed in 1999 from the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Pfeiffer 1975) used in the three previous years to the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh 1975). Within the chronically disabled population receiving help, there was a significant increase in cognitive impairment between 1984 and 1994, from about 34 percent to about 40 percent (Spector et al. 2000). This increase could be observed even in the presence of a decline in cognitive impairment in the population at large. In fact, during this period, the rate of full or partial proxy response, which often is the result of cognitive impairment, rose slightly between 1984 and 1994, whereas the overall rate of proxy response, including those who screened out of the survey, fell from about 23 to about 16 percent.

It may be more generally true that advances in technology and the greater availability of services in the economy reduce the reliability of a link between declines in IADL disability and improvements in health. The respondents’ perceptions of disability also may have changed for activities that are facilitated by environmental changes. In order to be classified as independent in an IADL activity, respondents to the NLTCS must either perform the activity or be able to perform it if they have to. Using grocery shopping as an example, in order for telephone or Internet shopping to result in a decline in reported disability, a respondent who orders groceries and has them delivered would have to consider that as doing their grocery shopping, rather than having it done for them. Another possibility that is difficult to investigate empirically is that respondents’ assessments of their ability to perform IADLs are influenced by whether help is available. If this is so and if the availability of caregivers has diminished over time, the result could be an observed downward trend in IADL-only disability.

Technological advances have affected how society at large performs various activities and almost certainly have contributed to observed declines in the prevalence of help with other IADLs. Again, the implication is not necessarily that health has improved. For example, the widespread availability of prepared foods and appliances like microwave ovens makes it both easier and safer to prepare meals without help, at any given level of health. Telephones with amplifying devices, touchtone dialing, and possibly the wider use of hearing aids almost certainly contribute to the smaller percentage of persons receiving help with telephoning. But despite the technological advances, there was no downward trend in getting around outdoors, with 6 to 7 percent of the elderly reporting help with this activity in each year. Similarly, the prevalence of persons receiving help in taking medications remained at about 5 percent in all years.

ADL Disabilities

In contrast to the finding for specific IADLs, there were no consistent declines in the prevalence of specific ADLs and few significant differences. As shown earlier, an increasing percentage of elderly people manage their ADL disability solely with the use of equipment. This appears to be attributable to only three activities: bathing, getting in and out of bed, and toileting.

The overall prevalence of persons receiving help with ADLs rose between 1984 and 1989 and fell thereafter, but this pattern did not apply to specific ADL items. There were significant increases in institutional help with bathing, dressing, getting in and out of bed, and toileting between 1984 and 1989, but only bathing showed a significant decline after 1989. The significant 0.5 percentage point increase in institutional help with dressing over the 15-year period was offset by a similar decline in community help, for no overall change in the prevalence of persons receiving help to get dressed. Only help with bathing showed an overall significant decline over the 15-year period, as the result of a 0.6 percentage point drop in the prevalence of community help. This decrease was more than offset by a 1.3 percentage point increase in the prevalence of persons who were independent with the use of equipment, however, so that the overall prevalence of persons with a disability in bathing did not change significantly. This is the only ADL activity for which increases in equipment use were accompanied by decreases in human help or supervision. The overall prevalence of persons with disability in getting in and out of bed and toileting rose, the result of a combination of the significant increase in the prevalence of institutional help with toileting and the significant increases in the use of equipment in the community for these two activities.

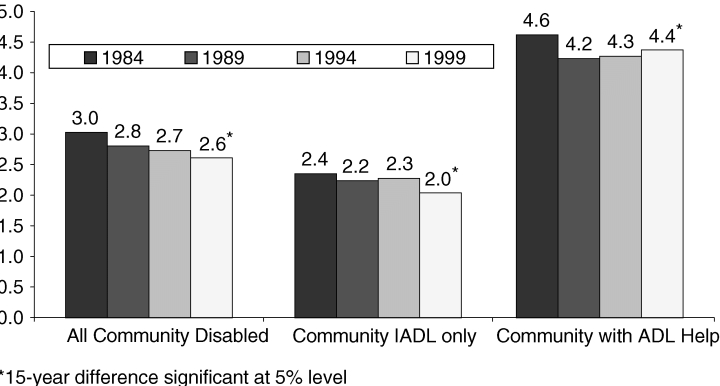

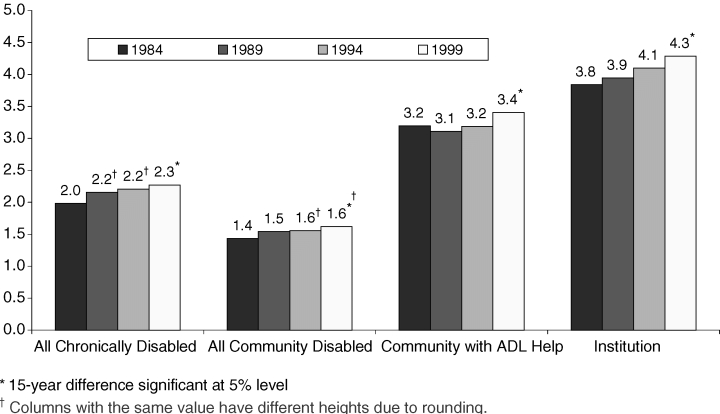

Mean Number of Disabilities

The potential cost implications of declining disability depend on not only the prevalence of disability but also the level of disability. For example, Spector and Fleishman (1998) found that the number of hours of long-term care received by chronically disabled community residents rose with the number of IADL and ADL disabilities for which help was received and that the total number of IADL and ADL disabilities predicted the number of hours of care better than did the number of ADLs alone. This section examines the average number of disabilities in IADLs, ADLs, and, for the relevant populations, total disabilities per person over the 15-year study period. The drop in the prevalence of disability in most IADLs suggests that the average number of IADL disabilities probably fell between 1984 and 1999. The lack of a downward trend in the prevalence of persons receiving help with specific ADLs, coupled with the slightly lower overall prevalence of persons receiving help with any ADL suggests, however, that the average number of ADLs with help is likely to have increased among those receiving help with ADLs. For the relevant populations from Table 4, the trend in the average number of IADL disabilities per person is shown in Figure 2, and the trend for the average number of ADLs with help is shown in Figure 3. Because IADL disability is not measured for institutional residents, the average IADL disabilities shown in Figure 2 are for community residents only.

Figure 2.

Mean Number of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) among Chronically Disabled Elderly Living in the Community, 1984–1999

Figure 3.

Mean Number of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) with Help among the Chronically Disabled Elderly, 1984–1999

The average number of IADL disabilities per person shows the expected downward trend for all disabled persons living in the community, with the largest five-year decrease between 1984 and 1989. The picture is less clear for the subsamples of community residents receiving help only with IADLs and those receiving help with ADLs. Although the average number of IADL disabilities per person receiving help only with IADLs was significantly lower in 1999 than in 1984, there was no downward trend before 1999. For community residents receiving help with ADLs, there was a decrease in the mean number of IADL disabilities between 1984 and 1989, but no trend since 1989. (The apparent slight increase in the mean number of IADL disabilities for this group since 1989 is not statistically significant.)

As expected, the mean number of ADLs per person rose overall for the community disabled, for community residents receiving ADL help, and for institutional residents, with the largest increase for institutional residents. For those receiving ADL help in the community, there appears to have been no trend before 1999, but both the overall increase in the average number of ADLs between 1984 and 1999 and the increase between 1989 and 1999 are significant.

Finally, the declines in the mean number of IADLs appear to have moderated these increases in the mean number of ADLs for the two subgroups—all community disabled and community residents receiving help with ADLs—for which the total number of disabilities in IADL or ADL activities can be measured. For all the community residents with disability, the average number of disabilities fell gradually from 4.5 to 4.2 over the 15-year study period, although only the cumulative decline over the whole period was significant (not shown). Conversely, for those receiving ADL help in the community, there was a significant drop in the mean number of ADL and IADL disabilities between 1984 and 1989, from 7.8 to 7.3, caused primarily by the precipitous drop in the mean number of IADLs during that period. This drop was followed, however, by a steady increase through 1999, so that the average total number of disabilities for which this group received help had returned to the 1984 level of 7.8 in 1999.

Discussion

Research in recent years has concluded that the aggregate rate of disability among the elderly has fallen, at least during some periods. By decomposing the aggregate trend shown in one data source closely associated with this conclusion, this study demonstrates that much remains to be understood before the drop in disability can be associated convincingly with savings in either Medicare or long-term care spending and before we can conclude that the rate of improvement seen in recent years will continue.

The results presented here support the need to look further into the underlying causes of the observed declines in chronic disability and to look directly at how the use of services and costs have changed. Most of the changes in disability between 1984 and 1999 were due to improvements in less severe disability, specifically in a lower prevalence of persons receiving help only with IADLs, thereby confirming the findings of research using other data (Freedman, Martin, and Schoeni 2002; Schoeni, Freedman, and Wallace 2001; Waidmann and Liu 2000). The prevalence of institutional residence did not show a downward trend, and the prevalence of persons receiving help with ADLs fell much less than the prevalence of persons receiving help only with IADLs and only after 1989. The prevalence of persons managing ADLs solely with equipment rose steadily between 1984 and 1999. This study, the first to examine trends in individual activities, found that nearly all the declines in disability in individual activities were for IADLs, with almost no change for individual ADLs.

Some of these findings regarding ADL disabilities have been confirmed by the work of a panel funded by the National Institutes of Aging, which produced and compared estimates for persons aged 70 or older from five national surveys, including the NLTCS, to determine whether they consistently found declines in ADL disability (Freedman et al. 2003). Time period, definition of disability, treatment of the institutional population, and age standardization were found to be important in explaining the disagreements in the estimates. A downward trend was found in the surveys for the 1990s for both difficulty performing ADLs and help with performing ADLs, but the evidence for the 1980s was mixed. Contrary to the findings in this study, the use of ADL equipment without help did not consistently show an upward trend across the surveys, and the evidence was mixed when ADL disability was defined as either receiving help or using equipment.

The findings in the current study may imply that not all of the downward trend in the aggregate rate of disabilities reflects better health. Rather, at least some of the observed declines are likely to reflect improvements in the environment that affect both the ability of the elderly to cope with activities associated with independent living and whether they perceive themselves to be disabled. The percentage of the chronically disabled reporting that their homes had modifications like grab bars and raised toilets increased between 1984 and 1999 (AARP 2003). If such features became more common among the aged population at large, it may have affected both the perception of disability and the receipt of help. It is also possible that changes in the availability of caregivers, owing to such demographic factors as the increasing proportion of women who are in the labor force, may have contributed to the rise in the use of disability equipment. If these types of changes in reporting occurred, they could have had effects beyond those measured in this study, which represent only those persons who “screened in” to the detailed questionnaire. For example, if technological advances changed either the respondents’ perceptions of their ability or their actual ability to perform an IADL, the number of persons screening into the detailed questionnaire also could have been affected.

Changes in public benefits may affect the costs of long-term care and may also affect whether help is received. The increase between 1984 and 1994 in the use of paid services among disabled community residents, including those with informal caregivers (Liu, Manton, and Aragon 2000; Spillman and Pezzin 2000), supports the possibility that average costs for the disabled rose. The increase affected all payers. The percentage of disabled elderly persons with formal caregivers who reported Medicare as a payment source rose from 16 percent in 1982 to more than 25 percent in 1994 (Liu, Manton, and Aragon 2000), and Medicaid programs also greatly increased their spending on community long-term care during this period. Out-of-pocket payments for freestanding home health care agencies also rose dramatically (Braden et al. 1998; Letsch et al. 1992).

Since 1994, Medicare’s spending on home health care has fallen in absolute terms owing to a combination of fraud and abuse detection and payment system changes in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (McCall et al. 2001), and the growth in spending by all other payers also has slowed (Cowan et al. 2001). My preliminary analysis of Medicare claims linked to the NLTCS suggests that spending on home health care in 1999 was 45 percent lower than in 1994, primarily because of dramatic declines in the number of visits per user. However, although growth may be slower, the decline in Medicare’s spending on home health care is likely to have been a temporary outcome of the interim payment system recently replaced by the prospective payment system. Medicare’s spending on home health care rose 14.4 percent in 2001, the first full year after prospective payment was put in place (Levit et al. 2003). Home health care services, however, represent only a fraction of all paid community long-term care. We need to examine further how the use of both home health and other paid home care has changed since 1994 and who has paid for such care.

The results of this study also suggest that we should undertake to understand better the relationships among disability, chronic conditions, and Medicare spending. Historically those people identified as disabled have had higher Medicare costs than have those without a disability. If, however, the reported reductions in less severe disabilities, particularly among the IADLs, as found here, reflect a more manageable physical environment rather than actual improvements in health, there is no reason to believe that total or per capita Medicare costs would fall. That is, a smaller proportion of any group defined by chronic conditions or poorer health status may report difficulties if it is simply physically easier for them to perform various activities because of changes in the external environment.

Using the 1984 and 1994 Supplements on Aging, Freedman and Martin (2000) and Crimmins and Saito (2000) found increases in various chronic conditions associated with disability. Freedman and Martin found that these increases were coupled with a decline in physical limitations such as reaching above the head or carrying a bag of groceries. Crimmins and Saito (2000) found declines in both physical limitations and IADLs for women, but not for men, and some significant increases in ADLs for both men and women. Both studies concluded that while some potentially disabling conditions that have increased in prevalence appeared to have become less debilitating, their earlier diagnosis and improved treatment may account for some of the apparent drop in the rate of disability associated with these conditions. Earlier diagnosis and improved treatments do not necessarily imply lower costs; indeed, they may mean higher costs. For example, the number of mobility-enhancing procedures like hip and knee replacements has risen dramatically in recent years, raising the possibility that disability improvements may have been purchased with higher Medicare spending. The finding here is that the overall prevalence of mobility problems rose and then fell, resulting in no net change at the end of the 15-year period examined. This pattern was entirely due to changes in the prevalence of independence with equipment, whereas the prevalence of persons receiving help with mobility was constant.

In an analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), Waidmann and Liu (2000) found evidence that the decline in the rate of disability was associated with smaller increases in per capita Medicare costs between 1992 and 1996. But they caution that the relationship between disability and the use of acute care is complex, so, for example, the expectation of a longer active life may prompt greater spending for restorative procedures, such as cataract surgery and joint replacements. A more direct analysis of the relationship among Medicare spending, chronic conditions, and disability is warranted. Surveys such as the NLTCS and the MCBS that can be linked to the history of Medicare claims are well suited for such an analysis, because they can be used both to examine repeated cross sections and to analyze successive cohorts over time.

Finally, the results regarding both equipment use and IADLs should be examined further, in part because they may reflect a margin of disability in which policies to promote environmental improvements can reduce dependence on help. The proportion of persons who manage all their ADL disabilities with equipment increased, as did the overall prevalence of persons using equipment for bathing, getting in or out of bed, and toileting. This greater use of equipment was, however, accompanied by a lower prevalence of human assistance only for bathing. It would be worthwhile to look at whether the use of equipment is associated with fewer hours of care for those who receive help but who can manage some activities independently with the use of equipment and what distinguishes those who can maintain their independence with the use of equipment from those who cannot. Agree and Freedman (2000) found that the use of equipment was positively related to disability level, more common among those using informal care, and most common among those using formal care. They found some evidence that simple devices like canes and walkers substituted for informal care and supplemented formal care. We need to know more about trends in equipment use and the relationship between specific types of equipment and the amount of long-term care.

Similarly, the strong downward trend in IADL disability, which accounts for nearly all the observed decline in the prevalence of disability, needs more careful study. In addition to examining the role of underlying health, physical limitations, and cognitive status in the decline of IADL disability, we should look at factors such as rising education levels, which recent studies using other data have found to be significantly related to the drop in disabilities (Schoeni, Freedman, and Wallace 2001; Waidmann and Liu 2000). The results in this study indicate that IADL disability is far less sensitive than ADL disability to the aging of the elderly population, even though several of the activities have a substantial physical and cognitive component. Also, some apparent inconsistencies are puzzling. For example, outdoor mobility, which is a physically oriented activity, and managing medications, which is more closely associated with cognitive difficulties or frailty, did not diminish, but money management and grocery shopping did.

Conclusion

A better understanding of the real implications of the decline in disability is not an academic exercise at a time when policymakers are considering changes in Social Security and Medicare in order to ensure their long-range financial health. Many argue that the declining disability rate should be taken into account in projecting future spending. How that should be done is unclear. The results reported in this study emphasize that we need to know more about what is driving the trends in specific aspects of disability before we can understand the implications for health care and long-term care costs.

We have not yet found empirical evidence of a direct link between the observed changes in the composition of disability and the health of the elderly. Similarly, we need to examine the complex relationship between changes in health of the elderly and health care costs. The implications of declining disability rates for the cost of long-term care are also still unclear. Changes in the types and intensity of long-term care due to changes in public programs, availability of formal and informal care, and upward shifts in the age distribution of the elderly may affect both their cost and the distribution of costs across payers.

The results here demonstrate the extent to which aging of the population has moderated the drop in age-specific disability rates. Between now and 2030, the percentage of elderly persons will increase from 13 percent of the population to 20 percent, according to Census Bureau projections. As the baby boomers age, the number of persons aged 85 or older will rise steadily from just under 2 percent of the population now to nearly 5 percent by 2050. Even if the observed improvements in physical functioning continue and research is able to demonstrate improved health and lower costs, the impacts on future health care and long-term care costs will be profound.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Office of Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP), Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Contract no, 100-97-0010). Findings from earlier versions were presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Health Services Research and Health Policy in Atlanta, June 2001; the 15th Private Long-Term Care Insurance Conference in Miami, August 2001; the Third International Conference on Family Care in Washington, D.C., October 2002; and the Joint Conference of the National Council on Aging and the American Society on Aging in Chicago, March 2003. The author acknowledges the research assistance of Heidi Kapustka and programming support from Mary Lee and Jeanne Yang and wishes to thank Vicki Freedman, William Marton, Korbin Liu, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the DALTCP or to the Urban Institute or its funders.

Appendix

Weight Adjustments for the 1984 and 1999 National Long-Term Care Survey

The weights provided on the public-use files for the 1984 and 1999 waves of the National Long-Term Care Survey (NLTCS) were created using poststratification methodologies different from those used for the 1989 and 1994 waves (Center for Demographic Studies 1989, 1996, 2001, 2003). If the publicly released survey weights are used, this affects the estimated trend in institutional residence over time, and to a lesser degree, it also affects disability trends. This appendix describes how the weights released for 1984 and 1999 differ from the weights for the other two years and how they were adjusted for this study to make the estimates more comparable over the four waves of the survey.

The NLTCS public-use files are constructed by the U.S. Census Bureau, under the direction of the Center for Demographic Studies (CDS) at Duke University, which then distributes the data files. In 1989, I and other researchers working with the 1984 NLTCS at what is now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality observed that the nursing home estimate from the survey (a subset of the NLTCS institutional questionnaire population) was large relative to the other available estimates. The public-use file weights were poststratified by age, gender, and race to cell counts from the external institutional and noninstitutional control totals provided by the census. The institutional questionnaire sample was poststratified to cell counts from the census’s institutional population estimate, and the community questionnaire sample was poststratified to cell counts from the census’s noninstitutional population estimate. After investigating the definition of institutional residence used to produce the census’s institutional control total, we concluded that this definition was broader than the definition used to assign NLTCS respondents to the institutional questionnaire. NLTCS respondents are assigned to the institutional questionnaire if they live in group quarters (three or more unrelated individuals) that have daily medical supervision, whereas the census’s definition included such settings as “rest homes for the aged” with no requirement for the number of residents or medical supervision (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1984a and 1984b). This disparity between the definitions of the sample and of the control total population had the effect of overstating the size of the institutional questionnaire population by weighting too narrow a subset of respondents to the institutional control total. Similarly, the community population estimates were affected because the noninstitutional control total was spread over too many respondents.

After discussions with the staff at the U.S. Census Bureau, my colleagues and I developed a strategy for selecting a sample more comparable to the institutional control total definition that we then poststratified to this control total to create a substitute 1984 weight. The U.S. Census later adopted this strategy and used it to construct the public-use file weights for the 1989 and 1994 waves of the NLTCS (Center for Demographic Studies 1989 and 1996). The adjustment expands the sample poststratified to the institutional control total to include two groups besides the institutional questionnaire respondents: (1) persons living in noninstitutional group settings that do not include daily medical supervision, provided they receive help with ADLs, on the assumption that this reasonably replicates the “homes for the aged” included in the control total but not in the NLTCS institutional questionnaire sample; and (2) all persons living in quarters identified as institutional but not providing medical supervision, since medical supervision is not a requirement for the control total.

The rest of the sample that received the community questionnaire and was not in one of these groups was then poststratified to the noninstitutional control total. The effect of the adjustment was to reduce the size of the institutional questionnaire population estimate and to increase the size of the community questionnaire population estimate. The adjustment reduced the 1984 institutional questionnaire population from 1.55 million to 1.41 million persons, and the nursing home population (a subset of the institutional questionnaire) from 1.51 million to 1.37 million.

In 1999, the CDS staff felt that the institutional control total originally provided by the census was too large and instructed Census staff to poststratify only the noninstitutional population to cell counts from an external control total (Center for Demographic Studies 2003). The institutional population was not poststratified to cell counts from an external control total, although proportions in each age, race, and gender cell were adjusted to match proportions from the census’s institutional estimate. The resulting 1999 institutional population estimate using weights distributed by the CDS is therefore not comparable to the estimates for previous years. To improve comparability in the current study, I created a substitute 1999 weight using the methodology described earlier for the substitute 1984 weight. (Detailed specifications for the 1999 reweighting are available from the author.)

The results of the reweighting are shown in Table A1, which compares published estimates for all years using survey weights with comparable estimates produced using the weights from this study. Estimates for 1999 were taken from Manton and Gu (2001). Because their estimates for 1984 to 1994 were age-standardized to the 1999 age distribution, the estimates in Table A1 for those years are estimates from Older Americans 2000 (Federal Interagency Task Force 2000) produced by the CDS for that publication.

Other than weights and inconsequential differences in editing, the estimates within each year differ analytically only with respect to the IADLs included in the IADL-only category, defined as having at least one chronic IADL limitation and no ADL limitation. In this study, IADLs exclude heavy housework and going beyond walking distance (transportation). Although footnotes to the estimates published in Older Americans 2000 indicate that both heavy housework and transportation were included, subsequent conversations with the CDS staff indicate that heavy housework was included only if other disabilities were present, so that the percentage with IADLs only would not be affected by its inclusion. Manton and Gu (2001) included the same IADLs as in Older Americans 2000. The impact of this analytic difference can be seen by focusing first on the 1989 and 1994 estimates, because for these estimates the weights do not differ. The institutional population estimates are identical, and within the community population, all the difference between the estimates in 1994, and all but 0.2 percent in 1989, is due to the difference in the IADL-only estimate.

The impact of the weighting adjustments can be seen in the 1984 and 1999 estimates. Considering 1984, as noted, the adjustment of the population poststratified to the institutional control total had the effect of reducing the estimate of the institutional questionnaire population from 5.5 to 5.0 percent of the elderly. The larger difference between ADL status in the community likely resulted from the tendency of the reweighting to increase the weights of those in the community who were not in the marginal groups included in the institutional poststratification and who may reasonably be expected to be less disabled than these marginal groups. In fact, the larger of the two marginal community groups included in the institutional sample as defined for reweighting—disabled elders in group settings without medical supervision—was selected in part based on having an ADL disability.

Three sets of 1999 estimates are presented. The first is the published estimates from Manton and Gu (2001); the second was constructed using cross-sectional file weights distributed by the CDS, and the third set of estimates uses the poststratified weight from this study. In this case, because the CDS weights include no institutional poststratification, the estimate of the nursing home population increases from just above 4 percent in the first two estimates to the 4.8 percent reported in my study. Because the weight distributed by the CDS includes the poststratification of the community sample to external cell counts, identically defined community estimates using this weight and the poststratified weight from the current study do not differ, and both differ from those published in Manton and Gu, primarily because of the IADL-only difference just discussed.

In the future, it would be preferable if a consistent set of weights for all the survey years were provided with the NLTCS data so that estimates would be comparable over time without adjustment of the weights. One strategy would be to remove all poststratification to control totals, thereby allowing the survey to generate an independent estimate of institutional residence. If the estimates are to be poststratified, identically defined control totals and poststratification methodology should be used over all the years. In addition, data from both the 1990 and 2000 censuses are now available. Ideally, the control totals for new poststratified weights would take them into account rather than relying on intercensal projections based on the 1980 and 1990 censuses, as is now the case.

TABLE A1.

Comparison of NLTCS Estimates in Older Americans 20001 and Manton and Gu (2001) with Estimates in Current Project

| 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older Americans 20002 | Spillman | Difference | Older Americans 20002 | Spillman | Difference | Older Americans 20002 | Spillman | Difference | Manton and Gu (2000)3 | Spillman (CDS final weight | Difference | Spillman Poststratified Weight4 | Difference | |

| Community | ||||||||||||||

| IADL only | 5.8 | 5.2 | −0.6 | 4.7 | 3.4 | −1.3 | 4.3 | 3.1 | −1.2 | 3.2 | 2.6 | −0.6 | 2.6 | −0.6 |

| 1–2 ADLs | 6.5 | 6.2 | −0.3 | 6.3 | 6.2 | −0.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 5.8 | −0.2 | 5.8 | −0.2 |

| 3–4 ADLs | 2.9 | 2.7 | −0.2 | 3.5 | 3.3 | −0.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | −0.1 | 3.5 | 3.4 | −0.1 | 3.4 | −0.1 |

| 5–6 ADLs | 3.1 | 3.0 | −0.1 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Any ADL | 12.5 | 11.9 | −0.6 | 12.6 | 12.4 | −0.2 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 12.3 | −0.1 | 12.3 | −0.1 |

| All community | 18.3 | 17.1 | −1.2 | 17.3 | 15.8 | −1.5 | 16.1 | 14.9 | −1.2 | 15.6 | 14.9 | −0.7 | 14.9 | −0.7 |

| Community and institution | 23.8 | 22.1 | −1.7 | 22.8 | 21.3 | −1.5 | 21.2 | 20.0 | −1.2 | 19.8 | 19.0 | −0.8 | 19.7 | −0.1 |

| Institution | ||||||||||||||

| All | 5.5 | 5.0 | −0.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 4.1 | −0.1 | 4.8 | 0.6 |

| IADL only | – | 0.2 | – | 0.2 | – | 0.2 | – | 0.1 | – | 0.1 | – | |||

| 1–2 ADLs | – | 0.9 | – | 0.8 | – | 0.7 | – | 0.3 | – | 0.4 | – | |||

| 3–4 ADLs | – | 1.0 | – | 1.1 | – | 1.0 | – | 0.9 | – | 1.1 | – | |||

| 5–6 ADLs | – | 2.9 | – | 3.4 | – | 3.3 | – | 2.7 | – | 3.2 | – | |||

Note: IADL (instrumental activity of daily living) only means inability to perform at least one IADL, but no help or equipment use for any ADL (activity of daily living). Those with ADLs may be using equipment or receiving either active or standby help.

Produced by Center for Demographic Studies for Federal Interagency Task Force on Aging-Related Statistics, Older Americans 2000: Key Indicators of Well-Being (http://www.agingstats.gov).

Estimates reproduced from Older Americans 2000 apparently include light housework, laundry, meal preparation, grocery shopping, getting around outside, financial management, using the telephone, taking medications, and transportation. Spillman estimates include the same items, except transportation.

IADLs apparently include all in Older Americans 2000.

The final weight is poststratified to Census totals using methodology consistent with that described in Census weighting specifications for the 1989 and 1994 survey waves. Cell counts for persons who are neither in an institutional residence nor disabled at screen and those who receive the community questionnaire but are not in any type of group quarters are adjusted to cell counts by age, gender, and race for the civilian noninstitutional population. Cell counts for persons who are disabled and living in noninstitutional group quarters (i.e., living with three or more unrelated individuals), those living in an institutional setting that does not have medical staff on duty daily, and those receiving the institutional questionnaire (i.e., those living in group quarters, including institutional settings, that have medical staff available daily) are adjusted to age, race, and gender for a population defined as the civilian population, excluding the civilian noninstitutional population and the population in correctional facilities. Persons in correctional facilities are out of scope.

References

- AARP. Beyond 50.03: A Report to the Nation on Independent Living and Disability. Washington D.C.: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2003. [accessed November 18, 2003]. Available at http://research.aarp.org/il/beyond_50_il.html. [Google Scholar]