Substance use during pregnancy poses substantial risks to the developing fetus and continues to generate considerable policy debate. Public policy responses to prenatal substance exposure (PSE) have varied depending in part on whether the substances in question are licit (e.g., tobacco and alcohol) or illicit (e.g., cocaine and heroin). The policy responses also have ranged from warning labels on the dangers to the developing fetus of using alcohol, to treating a pregnant woman's illicit substance use as child abuse. The most controversial case was Cornelia Whitner's criminal conviction in South Carolina for PSE after her newborn baby tested positive for cocaine metabolites. Although the conviction was upheld by the South Carolina Supreme Court, it is, to date, an isolated example (Whitner v. State of South Carolina, 492 S.E.2d 777 [S.C. 1997], cert denied, 523 U.S. 1145 [1998], but see Ferguson v. City of Charleston, 532 U.S. 67 [2001], and Ferguson v. City of Charleston, 308 F.3d 380 [4th Cir. 2002], ruling that PSE detection policies require the woman's informed consent).

One reason for the inconsistent policy responses to PSE is that the issues are entangled in the contentious debates over maternal and fetal rights. Clearly defined ideological fault lines have prevented a consensus on what obligations a pregnant woman owes to a fetus being carried to term. One side, led by maternal rights advocates, decries the negative impact of state intervention in PSE on the sanctity of a pregnant woman's privacy and other constitutional rights (Garcia 1997; Gomez 1997; Oberman 2000). These advocates are leery of conceding any role to the state in protecting the fetus that would interfere with a pregnant woman's liberty interests. The other side, led by fetal rights advocates, argues that the state's obligation to protect the development of a healthy fetal mind and body overrides the pregnant woman's privacy interests (Garcia 1997; Gomez 1997). This side seeks explicit fetal rights and protections. Evidence that coercive policies may actually harm the fetus by frightening women away from prenatal care complicates the issue (Chavkin 1990, 1991b, 1996).

Thoughtful analysts such as Oaks (2000) and Garcia (1997) have tried to reformulate the discourse surrounding PSE (see also Burtt 1994; Mathieu 1995, 1996). Oaks argues for a middle ground where the health outcomes of wanted fetuses taken to term are safeguarded while a woman's right to abortion is simultaneously affirmed. Her approach recognizes both that PSE (smoking is her focus) is harmful to pregnant women and their fetuses and that supporting PSE interventions entails social and political risks to women's rights. Garcia suggests that a public health approach to PSE could offer a way around the prevailing legal perspective that pits pregnant women, mothers, fetuses, and children against one another in courtrooms and state legislatures.

The framework that we propose in this article provides a systematic way for policymakers to think about PSE. We call our approach the reciprocal obligations framework because we argue that both the state, representing the fetus, and the pregnant woman have obligations that shape the limits of the state's intervention and the nature of the pregnant woman's response. Our framework is based on a public health model, meaning that the state's intervention should follow traditional public health strategies, such as prevention and treatment, as opposed to a criminal justice approach. A public health model emphasizes policies that will improve maternal and fetal health outcomes.

In this article, we first describe the policy debate surrounding PSE, which we define as the prenatal use of illicit substances. In the second section, we introduce our reciprocal obligations framework. We then analyze our proposed framework by examining the arguments for and against state intervention when substance use during pregnancy is suspected. Finally, we offer policy recommendations to those states trying to determine how best to respond to PSE.

The Policy Debate

Substance use during pregnancy is a risk factor for neurological and physiological harm to the fetus, which can result in developmental difficulties, learning problems, and continuing health problems (Castles et al. 1999; Leech et al. 1999; Milberger et al. 1998; Scher et al. 1998; Schuler and Nair 1999). From a policy perspective, pregnancy creates an opportunity to detect substance use and other risk factors for fetal health, since most pregnant women seek prenatal care (Guyer et al. 1999). Many women are more motivated to change their behavior during pregnancy because they recognize that their use of substances affects not only themselves but also their developing fetus.

Evidence of a pregnant woman's substance use can be obtained during prenatal visits or at birth. As a result, the state can intervene to reduce PSE at various stages. If evidence of PSE is obtained during pregnancy, interventions can be designed to reduce exposure to the fetus. But if evidence of PSE is not obtained until birth, the state's intervention will not be able to prevent harm to the fetus. In that case, the state's intervention should be designed to mitigate harm or manage negative birth outcomes.

In any event, the state's intervention depends on learning about the pregnant woman's substance use, which is usually detected when medical personnel identify PSE through prenatal visits or routine testing at birth. All states require medical personnel to report suspected child abuse to child welfare agencies. Only a few states specifically define PSE as child abuse, although some states have enacted legislation mandating a child abuse report if a toxicology screen at birth is positive (Zellman, Jacobson, and Bell 1997). No state requires systematic detection policies, such as toxicology screens for all pregnant women (Zellman, Jacobson, and Bell, 1997; Zellman et al. 1993), and only a few states have enacted legislation authorizing either civil commitment or detention of women for PSE (Minnesota: Minn. Stat. 253B.02 and 626.5561[1]; Wisconsin: Wis. Stat. 48.133; South Dakota: S.D. Codified Laws Ann. 34-20A-63, 64). Another way to think about this is that whereas some states take a public health approach (focusing on education, treatment, and counseling), others focus on criminal sanctions (Zellman, Jacobson, and Bell 1997). One survey of states suggests that the public health approach is yielding to more punitive state intervention (Chavkin, Breitbart, and Elman 1998), despite few criminal prosecutions.

This dilemma raises several policy questions. First, how should the state respond when PSE is detected and reported? Second, when should the state intervene? Third, what policies should the state devise to facilitate early detection? To date, most states have not clearly addressed these questions, in part because public policy has been forged without a social consensus regarding PSE and its sequelae.

Current policies regarding PSE have several shortcomings. The first is that both the legislation and the court rulings pertaining to PSE have an ad hoc quality about them. Beyond toxicology screens to determine PSE prevalence, state legislation rarely specifies detection policies or provides guidance on when the state should intervene. One result of this ad hoc quality is that physicians, who play a crucial role in detecting and reporting PSE to child welfare agencies, do not always know exactly what they are required to do regarding suspected PSE (Mendez et al. 2003; Zellman et al. 1999; Zellman, Jacobson, and Bell 1997). What these policies lack is a systematic framework that policymakers can use to design a consistent and sustainable PSE policy.

A second deficiency is that the policies were formulated without empirical evidence supporting any particular approach and with little attention to what is known about the effects of substances on fetal development and how these effects vary by substance. This point merits further reflection in light of the rhetoric that surrounded “crack babies” in the 1980s and the fact that much of the alarm generated was, in hindsight, unwarranted (Chavkin 2001; Frank et al. 2001). But even if PSE is not be as widespread or devastating as once thought, reducing pregnant women's dependence on substances and enhancing the well-being of pregnant women and their children remains an important public policy objective. In particular, interventions to reduce the risk of harm from PSE are most effective when provided early in the pregnancy. For instance, early detection and intervention can reduce a pregnant woman's substance consumption, provide better birth outcomes, and save money (Adams and Young 1999; Mullen 1999; Secker-Walker et al. 1998).

The third shortcoming is that the states#x2019; public policies typically vary by type of substance, licit versus illicit, with the use of licit substances only seldom penalized. This distinction between licit and illicit drugs is illogical if the concern is the health of the mother, fetus, and subsequent child (Garcia 1997; Taub 1994). Even though this distinction permeates the current policymaking environment, we contend that future policies should be based on the expected harm to the fetus, not on the type of substance. Indeed, the evidence suggests that some legal substances, for example, heavy alcohol use and exposure to tobacco products, may cause greater harm than illicit substances do (Fried 2002; Frohna, Lantz, and Pollack 1999; Kistin et al. 1996; Slotkin 1998). If the substance is legal, most states tend not to treat the harm to the fetus as evidence of child abuse. The exception is that some states treat fetal alcohol syndrome as evidence of child abuse, which could result in removing the child from parental custody. Wisconsin even prosecuted a woman for fetal alcohol syndrome (State of Wisconsin v. Zimmerman, 1996 WL 858598 [Wis.Cir. 1996]). However, in State of Wisconsin ex rel. Angela M.W. v. Kruzicki, 561 N.W.2d 729 (1997), the Wisconsin Supreme Court, as a matter of statutory construction (over a vigorous dissent), refused to permit the state to confine a pregnant mother after PSE was detected.

Conceptual Framework: Reciprocal Obligations

Our conceptual framework is based on the notion of reciprocal obligations. In this approach, both the state and the pregnant woman have obligations to the fetus and to each other. The foundation of this framework is that if the woman decides not to terminate the pregnancy, both the state and the pregnant woman must act in the best interests of the fetus. Although the state has a legitimate interest in enhancing birth outcomes, it cannot intervene with impunity, since its actions must take into account the pregnant woman's rights. Similarly, the pregnant woman cannot reject the state's intervention by asserting her privacy rights to the exclusion of her obligations to the fetus. More important, our framework moves away from the conventional and highly problematic dichotomies between the maternal rights and fetal interests that frame much of the PSE discourse. Instead of characterizing the issue as a maternal-fetal conflict, we substitute the framework of mutual obligations to optimize maternal and fetal/child health outcomes.

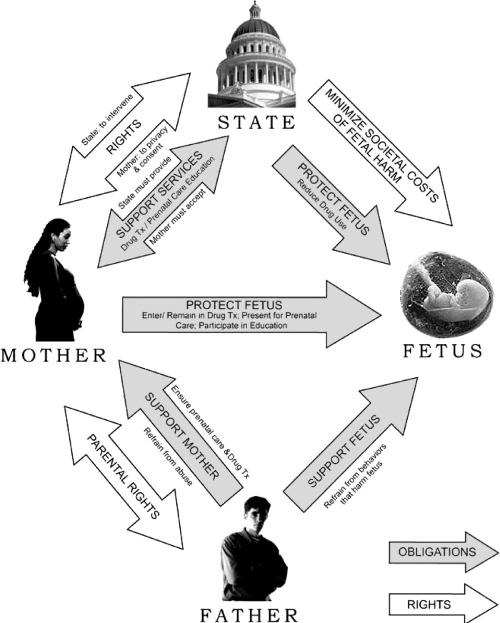

Schematically, the conceptual model is quite simple, as shown in figure 1. Explicit in this approach is that the key actors cannot assert any of their rights or interests before meeting a reciprocal obligation. For example, even if the state may want to prosecute the pregnant woman for PSE as child abuse, it cannot do so until it has met its obligation to provide the woman with adequate substance abuse treatment. Likewise, the pregnant woman has no right to object to increasingly stringent state sanctions for PSE if she refuses to accept treatment referrals or to remain in treatment. In this sense, our framework is based on tiered responses between the state and the pregnant woman. Once the state meets an obligation, it may exercise a corresponding intervention that requires a reciprocal obligation from the woman. Simultaneously, the pregnant woman can assert certain rights against more stringent state intervention. For our analysis, therefore, it does not matter whether the state or the pregnant woman is listed first because the obligations are reciprocal.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual Model of Reciprocal Rights and Obligations

In the interest of comprehensiveness, we have included both the fetus and the father. We included the father because paternal actions must be considered when formulating comprehensive policies designed to optimize fetal and child outcomes. The fetus has interests that both the state and the mother must protect, but it has no obligations. We included the fetus to illustrate all the parties#x2019; obligations. We should also point out that the potential costs and consequences of fetal harm are borne at least in part by society at large; the mother does not bear the full cost of such harm.

At the heart of our framework is the recognition that PSE policy must balance the various rights, interests, and obligations inherent in these relationships. To achieve an appropriate balance among the key actors#x2019; rights or interests and obligations, we offer the following guidelines. In developing policies, legislators and other policymakers must consider (1) the nature of the abridgment of rights (i.e., what type of intervention is being proposed); (2) the extent of the abridgment (i.e., how much the intervention infringes on the pregnant woman's autonomy); (3) the nature and costs of the public health benefits (i.e., how they will benefit the public and at what expense); and (4) alternatives to state intervention (i.e., the least intrusive means to achieve the state's objectives) (see also Gostin 2000, chap. 4).

Our framework also takes into account the contentious abortion debate in the United States. The reciprocal obligations theory we propose does not in any way impinge on the woman's unfettered pre-viability right to choose whether to take the fetus to term and the post-viability right to terminate the pregnancy to preserve the mother's life or health. In fact, our framework presumes that carrying a pregnancy to term is a choice. At the same time, the framework recognizes the state's interest in a potential life and its ability to regulate abortion short of placing an undue burden on the woman's choice (see Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 112 S. Ct. 2791 [1992]; and Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 [1973]). Arguing that the state retains certain interests once that decision has been made is not tantamount to arguing that the state has a right to interfere with the choice in the first instance.

One problem with the assumption of choice is the possibility that pregnant, substance-using women may not be capable of making such a rational choice or that such a choice is not widely available in practice, given geographic and financial constraints. For the purposes of our framework, this raises the question of how the state would know whether a substance-using pregnant woman had decided to complete her pregnancy. Frankly, there is no easy answer to that question. As long as the pregnant woman continues to carry the fetus, she has made a choice that will have certain consequences if she continues to ingest illicit substances. And as the pregnancy moves along toward viability and being taken to term, that choice becomes clearer, as do the reciprocal obligations. As Burtt asserted, “The care owed to the fetus is not dependent on the availability of this choice [of abortion] …. The ground of prenatal responsibility is rather the reasonable expectation (whether welcome or not) that the pregnancy will result in a live birth and a child to be cared for” (1994, 181).

The State's Interests and Obligations

When the use of PSE is detected, the state has a legitimate interest in taking action to make sure that the fetus taken to term is born with a sound mind and body. (We examine in a later section the rationale favoring and opposing the state's interests.) The question is what form that intervention should take. What is the proper scope of that intervention, and what are the state's reciprocal obligations to the pregnant woman?

Under the reciprocal obligations framework, the state's interest in preventing harm from PSE must be considered alongside its obligation to address the pregnant woman's needs. The state's obligations to the pregnant woman and her fetus differ depending on when PSE is detected. The rationale for such a distinction arises from the notion that prenatal detection may enable the prevention of harm from PSE, whereas perinatal detection permits only the management or mitigation of any effects of PSE.

Consonant with the potential for prevention, if PSE is detected during prenatal care examinations, the state is obligated to provide the pregnant woman with adequate prenatal care and substance-use treatment, paid for by the state when private insurance coverage is unaffordable or unavailable. To enhance positive birth outcomes, the state should ensure accessible prenatal care to all mothers.

If PSE is detected at birth, the state has the same treatment obligations, but the focus of intervention shifts to mitigating harm or managing negative birth outcomes. For instance, the state must dedicate resources to teaching parenting skills as a means of preventing neglect and abuse of the neonate, to preventing PSE in any subsequent pregnancies, and to mitigating any effects of PSE.

Regardless of when PSE is detected, states should adhere to a public health model based on the least restrictive alternative available and not punish the pregnant woman (Abel 1998; Blank 1996; Garcia 1997; Mathieu 1996). At a minimum, the intervention should be narrowly tailored to meet the state's objectives and to minimize interference with the mother's liberty interests. Thus, the state's intervention should focus on public health strategies, including education, counseling, treatment, developing parenting skills, and the like. By reducing the pregnant woman's dependence on drugs, the reciprocal obligations model is designed to improve the pregnant woman's health and, consequently, sound fetal development. Imposing penalties under child abuse laws is much less attractive and only a last-resort intervention, since its focus is solely on protecting the fetus, not on treating the parent. We argue later that the public health approach offers adequate alternatives to criminal prosecution.

Another important obligation for the state is to offer more opportunities to prevent or terminate pregnancies. For at least some substance users, pregnancy is unintended if not unwanted. Therefore, the state can help alleviate problems associated with PSE by offering adequate access to pregnancy prevention and termination services. While this may not be an obligation toward the individual woman with a substance-exposed fetus, it is an obligation toward the at-risk community. Not only is the state obliged to offer these services; it also has an interest in preventing additional PSE babies.

In an era of constrained state budgets, adequate funding may be a problem. But the states can take steps that do not require much money. For example, the states can try to educate pregnant women about their own and their developing fetus's health and to teach them parenting training and skills. These are secondary prevention services directed to women at risk. The states can also set performance and best practice standards for substance-abuse treatment facilities regarding access to services. To raise additional funds, the states might join foundations or other private-sector stakeholders to provide prevention and treatment services. The states can also combine funding sources to reduce the administrative costs of multipronged interventions. Finally, the states can raise taxes on licit substances, primarily to fill general revenue gaps.

The Pregnant Woman's Rights and Obligations

The pregnant woman retains considerable liberty and privacy rights to autonomy and reproductive freedom under the U.S. Constitution (especially the Fourteenth Amendment). But these rights are not absolute. From the public health perspective that underlies our approach, the pregnant woman's rights cannot be viewed or exercised apart from the state's interest in the developing fetus.

If the state, in our schema, has an obligation to provide adequate treatment referrals, the pregnant woman has a corresponding obligation to participate in the treatment, which overrides her right to privacy. This obligation and the abridgment of liberty that results from it are features of the state's interest in improving fetal outcomes and the pregnant woman's obligations to the fetus being carried to term. Other obligations depend on how the states respond to the pregnant woman's treatment regimen.

Based on our framework and on the general public health approach, the nature of the abridgment—namely, participating in outpatient substance-abuse treatment—is appropriate because the extent of the liberty abridgment is minimal and harm to the fetus is likely without the intervention. The pregnant woman's long-term health also may benefit, at a reasonable cost to society (Daley et al. 2001; Jansson et al. 1996).

If the pregnant woman participates in drug treatment but is unable to reduce or overcome her substance use or if she refuses treatment, the state may then consider whether the fetus's continued exposure will increase the likelihood of harm. If harm is deemed likely, either in the prenatal period or from the risk of postpartum neglect, the state may impose increasingly stringent public health measures, including isolation or mandatory treatment in a community-based facility. A public health approach allows the state to mandate residential treatment or require isolation, but this extraordinary action should be initiated only in extreme circumstances. In cases in which the pregnant woman simply refuses treatment or relapses, isolation or mandatory residential treatment may be an option. To be sure, these measures constitute a constraint of the mother's liberty, but without the stigma of a criminal prosecution.

Criminal prosecution is never appropriate for PSE because the state's criminal justice system cannot be assumed to adequately protect the fetus or to achieve the state's legitimate social goals (see, e.g., Chavkin 1991a, 1991b; Taub 1994). Incarceration does nothing to improve the pregnant woman's parenting skills, to increase understanding of her own or her infant's health and nutrition needs, or to promote maternal-infant bonding (unless the baby accompanies the mother to prison, which presents its own dilemma). Fear of incarceration may make a pregnant, substance-using woman less likely to seek prenatal care, which is associated with improved fetal outcomes even if her substance use continues (Chavkin 1991a, 1991b; Svikis et al. 1997). Since the substance use is often detected only because of the woman's pregnant status and her subsequent involvement in the health care system, punishing her for seeking health care would seem to undermine efforts at detection and intervention. Scholars also have identified the potential race and class inequities endemic to a criminal justice approach that focuses on the use of illicit substances, rather than a public health policy that focuses on prevention and treatment (Taub 1994). Finally, recent research suggests that drug treatment for nonviolent substance-use offenders is a much more cost-effective approach than incarceration is (CASA 2003). These arguments favor leniency and deference to civil liberties protections through a public health approach.

The Father's Rights and Obligations

Most of the articles dealing with PSE and related concerns fail to address the role of fathers and other involved men. Instead, they place all blame for prenatal injury and all social and legal responsibility for finding a solution on the pregnant woman (Garcia 1997; Taub 1994). But the complex roles that men play as “present or absent fathers, lovers, spouse batterers, enablers and co-participants in drug abuse” must be factored into policy if robust and durable solutions to PSE are to be found (Garcia 1997, 108).

The father's obligations are easier to specify than his rights. As a parent, the father ostensibly has the right to participate in decisions on how to raise the child and to participate with the mother in the prenatal and birthing process. But these rights are, at best, ambiguous and shed little light on the issues surrounding PSE, particularly when the father is not married to the mother.

In our framework, ambiguous paternal rights do not lessen the father's obligations to the fetus. Some of his most important obligations are not engaging in behaviors that directly and negatively affect the fetus's health, such as abusing the pregnant woman or encouraging her use of harmful substances. If the state is truly interested in optimizing fetal/child health outcomes, its public health policy must recognize the role of the father in unwelcome birth outcomes and must hold fathers responsible when appropriate. For instance, the father should be required to participate in parenting skills education and drug treatment programs. He also should be obligated to help the pregnant woman obtain prenatal care and substance abuse treatment and help her stop using illicit substances while pregnant.

Policy Analysis

The public health approach that underlies our reciprocal obligations framework is more likely than other strategies to create an optimal social policy and should form the conceptual basis for policy development. It is also the most effective way to move away from the prevailing paradigm that characterizes maternal-fetal interests as being in conflict. The public health approach can be used at each point in the process to clarify appropriate interventions once the state has met its obligations. Through proper primary prevention measures, more women can receive assistance before, during, and after pregnancy than they could under any alternative strategy.

With this policy model and our concomitant recommendations, we are seeking to establish a neutral ground in an attempt to forge a sustainable policy compromise. We are aware that this “splitting of the difference” will not likely satisfy the more ideologically polarized adherents of any particular position. We also recognize that this approach raises difficult problems of line drawing and the slippery slope. What is to prevent the state, for instance, from holding the pregnant woman and/or father responsible for exposure to workplace hazards, thereby reducing the family's income by forcing women of childbearing age to forgo certain job possibilities? Might the state hold women responsible for failing to seek proper prenatal care? Could the state go as far as to require certain nutrition or exercise regimens to protect the fetus's health?

These are legitimate concerns, yet we are convinced that for several reasons, our framework, which neither holds the interests of the fetus taken to term above the mother's rights, nor vice versa, will advance the public policy discourse regarding PSE. First, it will facilitate discussions among participants coming from different ideological positions. Second, it attempts to identify an acceptable solution that balances society's legitimate concerns regarding the effects of substance use on fetal development with the public health model that respects the pregnant woman's liberty interests and promotes a reduced dependence on licit and illicit substances. In contrast to the individual, after-the-fact application of the criminal justice model, the public health approach forces states to consider the population-based implications of a range of potential interventions. Third, an important advantage of our framework is that it is independent of the current scientific debates regarding the risk of fetal harm from PSE. It applies equally to licit and illicit substances and allows policymakers to adapt to changing empirical findings and political circumstances. Fourth, the slippery-slope concerns are less troublesome because some interventions (such as nutrition and exercise) would be trumped by the pregnant woman's privacy rights, while others, such as workplace restrictions, involve far more complex legal and legislative issues than our framework is designed to address. The purpose of our framework is to resolve problems related to substance use when the pregnant woman's personal freedoms are threatened. State intervention in these other instances would require an entirely different justification and analysis.

Summary of the Arguments in Favor of State Intervention

No one disputes that the state has an interest in the well-being of its citizens, especially children. What is contentious is whether the state can intervene to protect a developing fetus. Perhaps the strongest argument underlying the state's interest in PSE is the moral one. Stated simply, society has a moral obligation to reduce the risk of harm to children and is therefore entitled to punish actions that the community believes expose a child to such risk. In the case of PSE, the state is compelled to intervene because the pregnant woman has abdicated responsibility to her fetus because of her substance use. By intervening, particularly if the woman has rejected treatment, the state is exercising its moral obligation to promote sound fetal development (DeVille and Kopelman 1998). While it may not be fair to hold the pregnant woman, but not the father, responsible, the fact is that each stands alone and cannot abjure responsibility for his or her actions. Without resorting to coercion, no area of the law allows diminished responsibility because of the difficulty of punishing all responsible participants.

A second argument is that the states and the federal government have begun to address PSE in a more positive way. For instance, in the 1990s the states and the federal government began providing more money for drug treatment for pregnant women (although the states#x2019; current budget deficits may force some retrenchment in the years ahead). In addition, numerous demonstration projects are under way to provide drug treatment and teach parenting skills, suggesting that the barriers to treatment are being addressed (Breitbart, Chavkin, and Wise 1994; Howell et al. 1998). We are not suggesting that the government either has done enough to meet its obligations or should be allowed to use these efforts to justify punitive interventions. Instead, we recognize that the government is showing some signs of meeting its public health obligations under our framework, which would then support subsequent interventions as we just outlined.

A third argument for state intervention is that in certain civil cases, the courts have allowed parents to recover damages for fetal injuries. The courts also have held pregnant women accountable for the consequences of their substance-use behaviors. This tort activity, while contentious (Garcia 1997), has created considerable precedent. In a controversial decision, the Arkansas Supreme Court permitted a wrongful death lawsuit alleging that the plaintiff's wife and unborn child died during delivery because of medical negligence. The court held that a viable fetus, which suffered injury and was subsequently born alive, had a right to sue for injuries sustained during gestation. (Aka v. Jefferson Hospital Association, Inc., 42 S.W.3d 508 [Ark. 2001]. On the other hand, many states have laws preventing criminal or civil action for fetal injuries. See also, Bonbrest v. Kotz, 65 F. Supp. 138 [D.D.C. 1946].)

Most states have recognized the right to recover for injuries sustained prenatally, at least when a third party has caused the harm. For example, an Ohio trial court ruled that a two-year-old child could sue for damages from an automobile accident that occurred when she was in utero (Worden 2000). In a recent Michigan case, a criminal defendant was permitted to use the defense of protecting her unborn fetus (People of the State of Michigan v. Kurr, 654 N.W.2d 651 [Mich. App. 2002]). Although some courts have ruled that a neonate could sue the mother for harm during pregnancy, the current trend (as discussed in the next section) is to reject such cases. For our framework, the significance of these cases is that if courts permit parents to recover for fetal injuries, they may also be willing to permit some governmental intervention to protect the fetus from the potential harm caused by PSE. Besides these cases, the courts have consistently held that the state's interests in protecting the fetus become more compelling once the fetus attains viability and as delivery approaches (Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 [1973]; Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 112 S. Ct. 2791 [1992]).

A final—albeit less persuasive—argument in favor of state intervention in the case of illicit substances is simply that illegal activities can be sanctioned. Regardless of whether the harm to the fetus from legal substances (alcohol and tobacco) is greater than that from illegal substances, society has chosen to permit some activities while proscribing others. If a woman is engaging in a proscribed activity, the state is justified in using civil or criminal sanctions to eliminate the illegal conduct.

Summary of the Arguments against State Intervention

The most recent, and perhaps the strongest, statement of opposition to state intervention in PSE is from Nelson and Marshall (1998). While their arguments are primarily directed against incarceration, their ethical arguments are equally applicable to any state intervention beyond simply offering public health resources and programs. In addition to strong arguments favoring a pregnant woman's privacy rights and personal freedoms, they question the seriousness of fetal harm from cocaine, citing studies finding few if any long-term deficits to the child from PSE. Nelson and Marshall also argue that punitive policies unfairly target minority women for their substance use. Accordingly, the possibility of punitive measures or even mandated treatment may encourage substance-using women to refuse to obtain prenatal care or drug abuse treatment for fear of losing their neonate (and other children) or of being arrested.

Opponents of state intervention reject the state's moral claims on several grounds. First, opponents contend that an important argument against state intervention is the state's failure to provide adequate drug treatment for pregnant women. Second, they argue that PSE involves too many factors for society to easily blame just one person. Taub noted, for example, that “it is important to recognize that we are talking about addicts who have become pregnant, not pregnant women who choose to abuse drugs and other substances” (1994, 77). Third, philosophically, it is unlikely that addiction and autonomy can simultaneously coexist, thereby compromising the notion of a woman's choice to carry her fetus to term. Fourth, state intervention against pregnant women ignores the father's role in participating in or being responsible for the woman's drug use or dependence.

Many observers also argue that an increasing body of research suggests that PSE involving illegal substances produces birth outcomes that are no worse than PSE involving legal substances, even though the social outcomes are almost certainly worse (Frohna, Lantz, and Pollack 1999; Inciardi, Surratt, and Saum 1997; Zuckerman, Frank, and Mayes 2002). Indeed, there is growing evidence that the harm from prenatal exposure to alcohol and tobacco is greater than the harm from illicit substances (see, e.g., Abel 1998; Frohna, Lantz, and Pollack 1999; Slotkin 1998). This evidence seems as applicable to a “no-distinctions” policy in which the state may intervene in the prenatal use of either legal or illegal substances as it is to a “hands-off” policy under which the state may not intervene at all. Another objection cited by opponents of state intervention is that since harm to the fetus from PSE occurs primarily during the first trimester, the goal of avoiding future harm would not justify the substantial liberty infringements (Frohna, Lantz, and Pollack 1999; Abel 1998). In this view, much of the harm occurs before the woman may know she is pregnant.

Finally, opponents of state intervention contend that judicial decisions have not always favored state intervention to protect the fetus. For example, Illinois courts have refused to subordinate the woman's liberty interests to fetal rights. In In re Fetus Brown (689 N.E.2d 397 [Ill. App. 1997]; see also Stallman v. Youngquist, 531 N.E.2d 355 [Ill. 1988], and Levy [1999]), the court refused to sanction a forced blood transfusion against the patient's religious (Jehovah's Witness) beliefs. Even though the lack of a transfusion might have resulted in the fetus's death, the court refused to impose “a legal obligation upon a pregnant woman to consent to an invasive medical procedure for the benefit of her viable fetus.” While the court specifically noted that “this case does not involve substance abuse or other abuse by a pregnant woman,” other cases have explicitly rejected allowing a neonate to sue the mother for any harm resulting from PSE (Chenault v. Huie, 989 S.W.2d 474 [Tex. App. 1999]; State of Wisconsin ex. Rel. Angela M.W. v. Kruzicki, 561 N.W.2d 729 [Wis. 1997]).

Pursuing a Legislative Strategy

Our analysis strongly suggests that defining PSE as child abuse or incarcerating substance-using pregnant women is unlikely to alleviate the problem of PSE and its consequences. The policy response must focus on providing coherent and comprehensive public health services. Our reciprocal obligations framework argues that states must enact and implement a far more comprehensive legislative program to support and justify its intervention. A key problem with existing state legislation (and with tort activity) is its piecemeal nature and lack of comprehensiveness. As Zellman, Jacobson, and Bell (1997) pointed out, many states have responded to concerns about PSE by legislatively defining PSE as evidence of child abuse for child welfare investigations without addressing other aspects of the problem, especially the pregnant woman's need for drug treatment and parenting skills. In some instances, including cases in Maryland, California, New York, and Ohio, state courts have interpreted state statutes as including PSE as evidence of child abuse. To our knowledge, no state has enacted a comprehensive public health approach.

Under our framework, comprehensive PSE legislation not only must include a referral to treatment facilities but also must cover the cost of treatment for those unable to pay. Certainly, this places a burden on the state to provide an array of public health services. But if the goal is to prevent future PSE and to protect the fetus from additional substance exposure, adequate treatment resources must be a part of the overall legislative approach.

This is not to minimize the need to involve child welfare authorities in specific cases, but the states#x2019; definitions of child abuse should specify that PSE is evidence of child abuse, not child abuse per se. Prenatal substance exposure should be one of many elements that child welfare officials take into account during a child abuse and neglect investigation.

Another issue for legislators to consider is toxicology screening for all pregnant women who request prenatal care. Universal screening has an appeal on equity grounds, yet because it is costly, intrusive, and likely to yield high numbers of false positives, we do not recommend its adoption. Instead, we support state mandates to develop and implement hospital-based PSE protocols, which would allow the medical profession to develop appropriate and routine detection and referral practices. These practices would encourage physicians to become involved without fear of subjecting patients to punitive sanctions (Mendez et al. 2003). The medical profession is in the best position to determine the most effective mechanisms to detect and respond to PSE.

As part of the public health approach, states need to educate the public about fetal harm from alcohol and tobacco. Doing so will not only help alleviate current problems; it will also ease the transition to a harm reduction model over time. Once the public becomes more aware of the greater fetal harm from alcohol and tobacco relative to that from illicit substances, policymakers will be able to abandon the licit-illicit dichotomy that currently characterizes policy in favor of a more balanced and appropriate harm reduction strategy.

Limitations of the Reciprocal Obligations Framework

One serious limitation of the reciprocal obligations framework is that abortion is not equally available to all women. States are reluctant to provide funds for abortions, and many have imposed barriers to abortion services, such as mandatory waiting periods, leading to fewer abortion providers and the consequent need in some instances to travel considerable distances to obtain an abortion. These constraints are magnified for women who are substance users or addicts. This is a clear limitation for a framework that depends, at least to some extent, on the ability of substance-using women to make rational choices about continuing their pregnancy.

Thus, it might be argued that a model based on a rational choice to take the fetus to term, particularly when one is a substance-using, low-income woman, is unrealistic. Instead, decisions must be based on real options, and the lack of funds and the reality of addiction may exclude abortion as an option. At the same time, nothing in this framework compromises a woman's available rights to make different choices (or even multiple choices) during her pregnancy.

A second limitation of our framework is that few states have been willing to allocate enough money for drug treatment and other public health strategies. Even in states that do devote adequate resources, it is difficult to ensure that they are reasonably equally distributed across income levels. While both of these results may be true, neither undermines the public health approach we advocate.

A closely related concern is how the reciprocal obligations framework might be implemented. What enforcement mechanisms would be available to ensure that the states would provide adequate prenatal care, drug treatment, or parenting education? What recourse would a pregnant woman have if the state enforced its rights without meeting its obligations? A detailed discussion of these implementation issues is beyond the scope of this article, but the short answer is that the individual woman would be able to assert the state's failure to meet its obligations as a defense against the state's action. The burden would be on the state to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that it had met its obligations.

Third, since the harm from prenatal exposure to tobacco and alcohol is at least as great, and perhaps greater, than the harm from prenatal exposure to illicit substances, the state's claim to be protecting the fetus is illusory. Since most of the harm from PSE comes during the first trimester, well before many women know that they are pregnant, allowing the state to take civil or criminal action against a pregnant woman has two untoward consequences. For one thing, this appears to be action taken because of a woman's pregnancy status. For another, it seems inadequate, and perhaps ineffective, to deal with the problem of ensuring optimal birth outcomes. In other words, a harm reduction model makes more sense if the goal is to maximize the fetus's developing a sound mind and body. Still, our public health framework can be an effective strategy for preserving the pregnant woman's long-term health and her ability to care for her infant and for avoiding similar problems in subsequent pregnancies. Although our framework will not address all the harms that a mother and fetus may face, it may help reduce low-birth weight and its attendant consequences, as well as other biological and social harms that have not been addressed. Most important, our framework would encourage pregnant substance-using women to seek prenatal care early in their pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Harold A. Pollack, Ph.D., and Elizabeth A. Armstrong, Ph.D., for their insightful comments on a previous draft. We also want to thank Harold Zellman and Juan Calaf for preparing the figure and three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments. We appreciate the funding support we received from the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

References

- Abel EL. Fetal Alcohol Abuse. NY: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Adams EK, Young TL. Costs of Smoking: A Focus on Maternal, Childhood, and Other Short-Run Costs. Medical Care Research & Review. 1999;56(1):3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Blank RH. Maternal-Relationship: The Courts and Social Policy. Journal of Legal Medicine. 1996;14:73–92. doi: 10.1080/01947649309510904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart V, Chavkin W, Wise PH. The Accessibility of Drug Treatment for Pregnant Women: A Survey of Programs in Five Cities. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(10):1658–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtt S. Reproductive Responsibilities: Rethinking the Fetal Rights Debate. Policy Sciences. 1994;27:179–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00999887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASA. A CASA White Paper. New York: Columbia University; 2003. Crossing the Bridge: An Evaluation of the Drug Treatment Alternative to Prison (DTAP) Program. [Google Scholar]

- Castles A, Adams EK, Melvin CL, Kelsch C, Boulton ML. Effects of Smoking during Pregnancy: Five Meta-Analyses. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(3):208–15. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W. Drug Addiction and Pregnancy: Policy Crossroads. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(4):483–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W. Drug Abuse and Pregnancy: Some Questions on Public Policy, Clinical Management, and Maternal and Fetal Rights. Birth. 1991a;18(2):107–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W. Mandatory Treatment for Drug Use during Pregnancy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991b;266(11):1556–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W. Mandatory Treatment for Pregnant Substance Abusers: Irrelevant and Dangerous. Politics and the Life Sciences. 1996;15:53–4. doi: 10.1017/s0730938400019614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W. Cocaine and Pregnancy—Time to Look at the Evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:1626–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin W, Breitbart V, Elman D. National Survey of the States: Policies and Practices Regarding Drug-Using Pregnant Women. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(1):117–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M, Argeriou M, McCarty D, Callahan JJ, Jr, Sheoard DS, Williams CN. The Impact of Substance Abuse Treatment Modality on Birth Weight and Health Care Expenditures. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33:57–66. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVille KA, Kopelman LM. Moral and Social Issues Regarding Women Who Use and Abuse Drugs. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 1998;25:237–54. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, Pell T, Zuckerman B. Growth, Development, and Behavior in Early Childhood Following Prenatal Cocaine Exposure: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:1613–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA. Adolescents Prenatally Exposed to Marijuana: Examination of Facets of Complex Behaviors and Comparisons with the Influence of in utero Cigarettes. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2002;42(suppl):97–102S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohna JG, Lantz PM, Pollack H. Maternal Substance Abuse and Infant Health: Policy Options across the Life Course. Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77(4):531–70. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S. Ethical and Legal Issues Associated with Substance Abuse by Pregnant and Parenting Women. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1997;29(1):101–11. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1997.10400174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L. Misconceiving Mothers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Guyer B, Hoyert DL, Marin JA, Ventura SJ, MacDorman MF, Strobino DM. Annual Summary of Vital Statistics. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1229–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EM, Thornton C, Heiser N, Chasnoff I, Hill I, Schwalberg R, Zimmerman B. Pregnant Women and Substance Abuse: Testing Approaches to a Complex Problem. 1998. [accessed May 2000]. Available at http://www.mathematica-mpr.com.

- Inciardi J, Surratt H, Saum C. Cocaine-Exposed Infants. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson LM, Svikis D, Lee J, Paluzzi P, Rutigliano P, Hackerman F. Pregnancy and Addiction: A Comprehensive Care Model. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13:321–9. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistin N, Handler A, Davis F, Ferre C. Cocaine and Cigarettes: A Comparison of Risks. Pediatric & Perinatal Epidemiology. 1996;10(3):269–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1996.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech SL, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Prenatal Substance Exposure: Effects on Attention and Impulsivity of 6-Year-Olds. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1999;21(2):109–18. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(98)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu D. Mandating Treatment for Pregnant Substance Abusers: A Compromise. Politics and the Life Sciences. 1995;14:199–208. doi: 10.1017/s0730938400019092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu D. Pregnant Women in Chains? Politics and the Life Sciences. 1996;15:77–81. doi: 10.1017/s0730938400019717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D, Jacobson PD, Hassmiller KM, Zellman GL. The Effect of Legal and Hospital Policies on Physician Response to Prenatal Substance Exposure. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2003 doi: 10.1023/a:1025188405300. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Jones J. Further Evidence of an Association between Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Findings from a High-Risk Sample of Siblings. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27(3):352–8. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PD. Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy and Evidence-Based Intervention to Promote Cessation. Primary Care; Clinics in Office Practice. 1999;26(3):577–89. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J, Marshall MF. Ethical and Legal Analyses of Three Coercive Policies Aimed at Substance Abuse by Pregnant Women. Charleston, S.C.: 1998. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Oaks L. Smoke-Filled Wombs and Fragile Fetuses: The Social Politics of Fetal Representation. Signs. 2000;26:63–108. autumn. [Google Scholar]

- Oberman M. Mothers and Doctors#x2019; Orders: Unmasking the Doctor's Fiduciary Role in Maternal-Fetal Conflicts. Northwestern University Law Review. 2000;94:451–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher MS, Richardson GA, Robles N, Geva D, Goldschmidt L, Dahl L, Scalabassi RJ, Day NL. Effects of Prenatal Substance Exposure: Altered Maturation of Visual Evoked Potentials. Pediatric Neurology. 1998;18(3):236–43. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler ME, Nair P. Brief Report: Frequency of Maternal Cocaine Use during Pregnancy and Infant Neurobehavioral Outcome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1999;24(6):511–4. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/24.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secker-Walker RH, Vacek PM, Flynn BS, Mead PB. Estimated Gains in Birth Weight Associated with Reductions in Smoking during Pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1998;43(11):967–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Fetal Nicotine or Cocaine Exposure: Which Is Worse? Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;285(3):931–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svikis D, Golden AS, Huggins GR, Pickens RW, McCaul ME, Velez ML, Rosendale CT, Brooner RK, Gazaway PM, Stitzer ML, Ball CE. Cost-Effectiveness of Treatment for Drug-Abusive Pregnant Women. Drug and Alcohol Dependency. 1997;45(1–2):105–13. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub N. Prenatal Treatment and Mothers#x2019; Rights: The Legal Framework, Policy Considerations, and Research Needs in Three Problem Areas. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1994;736:74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb12819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden A. Fetus Can Sue, Judge Says. APBnews.com. 2000. [accessed July 31, 2000]. Available at http://www.apbnews.com/newscenter/breakingnews/2000/07/31/fetus0731_01.html.

- Zellman GL, Bell RM, DuPlessis H, Hoube J, Miu A. Physician Response to Prenatal Substance Exposure: Prevalence and Reasons. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 1999;3(1):29–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1021810129171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellman GL, Jacobson PD, Bell RM. Influencing Physician Response to Prenatal Substance Exposure through State Legislation and Workplace Policies. Addiction. 1997;92(9):1123–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellman GL, Jacobson PD, DuPlessis H, DiMatteo MR. Detecting Prenatal Substance Exposure: An Exploratory Analysis and Policy Discussion. Journal of Drug Issues. 1993;23(3):375–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman B, Frank DA, Mayes L. Cocaine-Exposed Infants and Developmental Outcomes: “Crack Kids” Revisited. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287:1990–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]