Abstract

Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) of prescription drugs in the United States is controversial. Underlying the debate are disagreements over the role of consumers in medical decision making, the appropriateness of consumers engaging in self-diagnosis, and the ethics of an industry promoting potentially dangerous drugs. Drug advertising and federal policy governing drug advertising have both responded to and reinforced changes in the consumer's role in health care and in the doctor-patient relationship over time. This article discusses the history of DTCA in the context of social movements to secure rights for health care patients and consumers, the modern trend toward consumer-oriented medicine, and the implications of DTCA and consumer-oriented medicine for contemporary health policy debates about improving the health care system.

Keywords: Direct-to-consumer advertising, patients, consumers, rights, consumerism, prescription drugs, regulation, Food and Drug Administration, pharmaceutical industry

American consumers are bombarded daily with advertisements for prescription drugs that treat high cholesterol, diabetes, depression, pain, erectile dysfunction, and a host of other conditions. While the majority of pharmaceutical promotional expenditures is still aimed at physicians, spending on direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs increased dramatically from $166 million in 1993 to $4.2 billion in 2005 and now makes up nearly 40 percent of total pharmaceutical promotional spending (IMS Health 2006). Moreover, for some drugs, direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) makes up the bulk of promotional spending (Ma et al. 2003).

The increased use of mass media advertising for prescription drugs has been controversial. Opponents of DTCA argue that it misleads consumers into taking costly prescription drugs that they do not need and that in seeking to sell products, pharmaceutical marketers turn normal human experiences with things like hair loss or shyness into diseases (Angell 2004, 123–26; Mintzes 2002). Then, after the September 2004 withdrawal of Vioxx due to evidence of increased cardiovascular risk, critics called for at least a partial ban on DTCA (Saul 2005). In contrast, advocates of DTCA argue that prescription drug ads are an appropriate and highly valued source of information for empowering health care consumers (Bonaccorso and Sturchio 2002; Holmer 1999, 2002).

Underlying this policy debate are profound disagreements over the role of consumers in medical decision making, the appropriateness of consumers engaging in self-diagnosis, and the ethics of an industry promoting potentially dangerous drugs. Over the last three decades, important reforms of the health care system have secured patients' rights to information about treatment options (informed consent) and purchasing decisions. Some bioethicists and historians of the patients' and consumers' rights movements in health care have suggested that the pharmaceutical industry co-opted these movements by means of DTCA, disingenuously using the language of individual rights to support commercial activities (Halpern 2004; Rothman 2001). But these commentaries do not provide a historical perspective on how DTCA came about or what makes it so controversial despite recent expansions of the consumer's role in health care. Similarly, even though histories of DTCA and the regulation of drug advertising have been published (Palumbo and Mullins 2002; Pines 1999), they do not trace the changes in pharmaceutical advertising along with the evolution of the health care consumer. Bringing together the history of the patients' and consumers' rights movements in health care with the history of drug advertising and its regulation should further our understanding of (1) why the pharmaceutical industry, which for decades had focused its promotional efforts solely on physicians, began investing heavily in influencing consumers; (2) why the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allowed DTCA to expand as it did; and (3) why some stakeholders see DTCA as threatening the doctor-patient relationship. While the evolution in the consumers' roles in health care was certainly not the only factor influencing the pharmaceutical industry or the FDA, I argue that it was nonetheless a necessary condition.

In the first section of this article, I define the terms patient and consumer and discuss the movements to bolster the rights of patients and consumers in medical care. Second, I trace the key points in the history of federal drug regulation. Over time, federal regulators have responded to and reinforced changes in the roles of patients and consumers, most notably in how they regulate drug labeling and advertising. The third section of the article follows DTCA from the early 1980s to the present and provides evidence of shifts in the views of consumer groups, physicians' organizations, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and the Food and Drug Administration during this period. These changing views reflect advances made by the patients' and consumers' rights movements as well as the current challenges facing them. I conclude by exploring the wider implications of DTCA and consumer movements for contemporary health policy debates over how to improve the quality of and access to health care.

Patients and Consumers and Their “Rights” to Information

The central thesis of this article is that the pharmaceutical promotion of prescription drugs to consumers was made possible by the rise of consumer-oriented medicine following the social movements for patients' and consumers' rights. The term consumer-oriented has been used to describe everything from efforts to give individuals more responsibility for their health care expenditures (e.g., consumer-directed health plans) to initiatives to promote shared decision making between doctors and patients. Accordingly, I should explain what I mean by the terms patient, consumer, and consumer-oriented medicine (or consumerism).

My point of departure is Wendy Mariner's legal definition of consumers and patients (1998). According to her, consumers are buyers of goods and services. Although historically patients have also been buyers in that they have paid for some if not all of their health care, they were not considered consumers until recently. A patient is a recipient of a health care service (Mariner 1998). Some people use the term consumer to refer to the buying role (e.g., educating consumers about their health plan choices). Other people use the term as a substitute for patient because the latter term implies subservience to health care professionals, although no economic role is attached to the consumer in this usage.

Whereas the distinction between the terms patient and consumer is often blurred, the differences between the legal rights of patients and consumers are clearer. Furthermore, although entitlement to information is central to both the patients' and consumers' rights movements, the goals of providing this information are different. Mariner (1998) contends that the main tool of consumer protection laws is the disclosure of information in order to level the playing field between buyers and sellers (Mariner 1998). The rights of patients, she points out, developed outside the context of commercial markets, independently of health insurance, and without regard to the existence or source of payment for health care. Ordinarily a patient is in a relationship with a physician or other health care professional. Mariner (1998, 4) states that

the law of patients' rights does not seek to give patients and physicians equal medical knowledge. Instead the law accepts inequality and protects patients by imposing on physicians a fiduciary duty to use their skills only in the patients' best interest and provide services that meet professionally accepted standards. In contrast, businesses do not have fiduciary obligations to their consumers.

The goal of the patients' rights movement in the 1970s was to require health professionals to provide information to patients about their treatment options. In contrast, the goal of the consumers' rights movement in the 1990s was to require health insurance companies to provide information about benefits and policies. The first DTCA campaigns were launched in the early 1980s after the patients' rights movement had taken hold but before the era of consumer rights had begun. In effect, DTCA blends elements of both the patients' and consumers' rights movements, although I argue that it is partly an unintended consequence of these social movements; that is, it is a vehicle for pharmaceutical manufacturers to tell end users about their products. This seems to parallel efforts to secure consumers' rights, which ultimately aim to improve the functioning of markets.1 For DTCA to be effective (from the pharmaceutical industry's perspective), these ads must expand patients' knowledge and influence over medical decision making, which is ostensibly a major goal of patients' rights movements. However, as Mariner notes, patients' rights movements have focused on requiring health professionals to give patients information, not to help businesses market their products. Because of the unique history of prescription drugs and physicians' important role as intermediaries between drug manufacturers and patients for more than a half century, DTCA represents a challenge to physicians' roles as agents for their patients. Next I discuss how this physician agency relationship was created during the twentieth century through federal drug regulation.

Federal Drug Regulation

I begin my account of federal drug regulation in the early twentieth century for two reasons. First, DTCA and other forms of pharmaceutical promotion are heavily regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, as its authority to regulate advertising is closely related to its authority to approve prescription drugs, the primary means through which the FDA ensures public health and safety in the use of pharmaceuticals. The federal regulation of drugs began in 1906 and was expanded with three major pieces of legislation between 1938 and 1962. Because changes in the way that companies promoted drugs are closely tied to these expansions in regulatory authority, they warrant a brief explanation. Second, criticism of DTCA is related to the fact that the promoted products are available only by a doctor's prescription. Advertising for over-the-counter medicines, though prevalent, has not engendered the same level of controversy because they are considered safe for consumers' self-directed use. The modern distinction between over-the-counter and prescription medicines, which stems from legislation passed in the 1950s, is, therefore, a crucial part of the story.

The Context of Early Drug Regulation

The federal regulation of drugs began when only a few effective drugs were on the market, and patients usually chose the medication themselves (Shorter 1991). Then, in the early twentieth century, the clear roles of physicians as prescribers and pharmacists as dispensers were not as clearly distinct as they are today. At that time, consumers could obtain drugs by seeking a prescription from a doctor and filling it at a pharmacy, as they do now. State medical licensing laws, which were passed in the mid- to late nineteenth century, gave physicians the authority to write prescriptions. It is important to note, however, that a prescription was not required, so almost any drug that could be obtained with a prescription could also be obtained without one.2 Prescriptions, in other words, “were a convenience to be used or not as the situation indicated” (Temin 1980, 23). Furthermore, consumers could obtain a drug compounded by a pharmacist but did not need a doctor's prescription. Physicians were also in the business of dispensing drugs during this time, and thus a third and final way that consumers could obtain drugs was directly from a doctor. Thus doctors did not play the same gatekeeping role in drug consumption that they do today.

In the early twentieth century there were two classes of drugs. Those in the first group, which were later dubbed “ethical” drugs by the American Medical Association, were listed in the United States Pharmacopoeia (USP). The USP is a compendium of standard drugs first established in 1820 by eleven physicians who met in Washington, D.C. Of the many drugs originally listed in the USP, only a few are still considered today to be “effective” and include digitalis, morphine, quinine, diphtheria antitoxin, aspirin, and ether (Temin 1980). The other class of drugs in the early twentieth century was patent or proprietary medicines, which were made of unknown ingredients under trademarked names (e.g., Lydia Pinkham's Vegetable Compound, Hamlin's Wizard Oil, Kick-a-poo Indian Sagwa, Warner's Safe Cure for Diabetes). The main ingredient of many of these tonics, salves, and bitters was water, plus in some products addictive substances such as alcohol or opium (Young 1961).

Manufacturers promoted these two classes of drugs very differently. Patent medicine makers were prolific advertisers, and at the turn of the century, ads for their products accounted for roughly half of newspapers' entire advertising income (Young 1961). These advertisements routinely made exaggerated claims about the effectiveness of their products and seldom disclosed their ingredients or risks. For instance, an advertisement for Lydia E. Pinkham's Vegetable Compound claimed “to cure entirely the worst form of female complaints, all ovarian troubles, Inflammation and Ulceration, Falling and Displacements. And the consequent spinal weakness, and it is particularly adapted to the change of life.”3

Although many of these advertising messages invoked positive images of doctors and the promise of new medical science, most pharmaceutical advertising still emphasized self-treatment. James Harvey Young (1961, 169) provides examples of how patent medicine advertisers differentiated their treatments from those of doctors:

Wherever regular physicians were weak, lo, there the nostrum maker was strong. Their therapy was brutal, his was mild. Their treatment was costly, his was cheap. Their procedures were mysterious, his were open. Their prescriptions were in Latin, his label could be read by all. Their attack on illness was temporizing, his was quick.

Ethical pharmaceuticals, in contrast, were not advertised to consumers in part because of the efforts of organized medicine. In 1905, the American Medical Association (AMA) established the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry, which set standards for drugs and then evaluated them (Young 1961). The council's goal was to steer patients toward using effective pharmaceutical preparations prescribed by physicians and to discourage their using ineffective, self-administered patent medicines. The AMA urged physicians not to prescribe, and medical journals not to run advertisements for, drugs that were “advertised directly to the laity” (Journal of the American Medical Association 1900). The AMA regarded self-medication as a threat to the medical profession. Therefore, by categorizing drugs advertised solely to physicians as “ethical,” the AMA created an incentive for pharmaceutical companies to focus their promotional efforts on physicians. At the heart of these efforts were the goals of reducing self-treatment and encouraging deference to professional medical judgment (Starr 1982).

The 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act

Federal drug regulation began in the Progressive Era, during which a new faith in the scientific enterprise and a belief in active, informed consumers reigned (Pescosolido and Martin 2004). The objective of the first federal drug legislation was not to discourage self-medication, as organized medicine wished to do, but to give consumers more information so that they could identify effective medicines (Temin 1980; Young 1981). The 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act also prohibited the interstate transport of unlawful food and drugs. The basis of this law rested on the regulation of product labeling rather than premarket approval, as would later be the case. Drugs, defined in accordance with the USP's standards of strength, quality, and purity, could not be sold in any other condition unless the specific variations from the standards were stated on the label. Also, no detail of a drug label could be false or misleading, and it had to list the presence and amount of eleven dangerous substances, including alcohol, heroin, and cocaine. But in 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in U.S. v. Johnson that the 1906 act did not prohibit false therapeutic claims but only false and misleading statements about the ingredients or identity of a drug. The Sherley Amendment, which was passed by Congress in 1912, overruled the Supreme Court's ruling by prohibiting labeling medicines with false therapeutic claims intended to defraud the purchaser. It was difficult, however, for the federal government to prove intent to defraud, and so the advertising provisions of the 1906 act had little effect on the behavior of the patent medicine industry.

The 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

By the 1930s, federal drug regulators had abandoned the belief that consumers, armed solely with information about a drug's ingredients, could safely self-medicate. Throughout the decade, FDA officials, supported by New Deal activists including newly founded consumer groups (e.g., the National Consumers League), tried to expand federal authority over drugs. After more than one hundred people died after taking a drug called elixir sulfanilamide, Congress passed the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) which required, for the first time, that drugs had to be proven safe and to receive the FDA's approval before they could be marketed. Opponents of the legislation claimed the act would abridge the sacred right of consumers to self-medicate (Jackson 1970). The FDCA also expanded the concept of drug “labeling” to include more than the drug's name and a list of ingredients. It stated that drug labeling must include adequate directions for use and that these directions had to appear on the package with “conspicuousness and in terms such as to render it likely to be read and understood by the ordinary individual under customary conditions of purchase and use.” These requirements for labeling are similar to those for what we would now refer to as “over-the-counter” (OTC) products more than to prescription drugs (Juhl 1998). However, the FDCA gave the FDA the authority to publish regulations exempting certain drugs from the labeling requirement, and in 1938 the FDA issued regulations stating that exempted drugs must include the warning “Caution: to be used only by or on the prescription of a physician, dentist, or veterinarian,” and the directions for use had to employ medical terminology that would not likely be understood by an ordinary person (Swann 1994). Neither the FDCA nor its accompanying regulations, however, define what drugs were to be available by prescription, nor do they clarify the distinction between prescription and OTC drugs.

Requiring Prescriptions: Durham Humphrey Amendments

Before 1951, the categorization of a drug as available by either prescription or OTC was left up to the manufacturers, although the FDA did require some drugs to be sold by prescription only (e.g., sulfa drugs in the 1930s) (Goodrich 1986; Juhl 1998). The lack of a clear distinction between prescription and OTC drugs led to confusion by both consumers and pharmacists and also variations in how drugs were categorized (Goodrich 1986). By 1941, FDA officials had identified more than twenty drugs or groups of drugs they considered too dangerous to sell except with a physician's prescription (Swann 1994). In 1951, Congress passed the Durham Humphrey Amendments to the FDCA, which created a statutory definition of prescription drugs to include those that “because of [their] toxicity or other potentiality for harmful effect, or the method of [their] use, or the collateral measures necessary to [their] use, [they are] not safe for use except under the supervision of a practitioner licensed by law to administer such drug[s]” (Public Law 82-215, 65 stat 648).

After the Durham Humphrey Amendments became law, more drugs were sold by prescription but did not carry the full product labeling that OTC drugs did. Instead, the primary purpose of the amendments was to avoid patient self-diagnosis and self-administration of complex and potentially harmful drugs (Kendellen 1985). Indeed, FDA officials viewed some drugs as potentially so dangerous that no amount of information provided to consumers would make self-medication safe. The labeling instead would be directed to pharmacists and physicians who in turn would provide information to the patient. Thus, a paradoxical situation developed in which potentially dangerous prescription drugs were dispensed to consumers with less accompanying information than OTC drugs carried (IOM 1979). The view of federal drug regulators that requiring prescriptions was an important means of protecting consumers coincided with the AMA's long-held objective of securing more control by physicians over the use of pharmaceuticals (Starr 1982; Temin 1980).

The Impact of Federal Policy on Pharmaceutical Marketing

Between 1938 and 1951, federal drug legislation and regulation had a significant impact on the market for drugs, and between 1929 and 1949, the amount of money that consumers spent on drugs prescribed by doctors rose from 32 to 57 percent. By 1969, prescription drugs made up 83 percent of consumer spending on pharmaceuticals (Temin 1980, 4). Finally, between 1939 and 1959, drug sales rose from $300 million to $2.3 billion, with prescription drugs accounting for all but approximately $4 million of the increase (Rehder 1965). Self-medication, which in the early twentieth century was widespread and viewed as a “sacred right,” now took a backseat to the pharmacological treatments guided by physicians after World War II.

Once drugs were made available only through a physician's prescription, the pharmaceutical companies stopped advertising directly to patients and instead channeled all their promotions to health professionals. By the 1960s, more than 90 percent of the pharmaceutical companies' spending on marketing was aimed at doctors (with the rest targeting pharmacists and hospitals), a complete reversal of the pattern thirty years earlier (Hilts 2003). Now the bulk of pharmaceutical promotional spending was on sales representatives called “detail men,” pharmaceutical sales representatives who visited physicians' offices, and on advertising in medical journals. Thus, federal regulation granted physicians authority not only over access to prescription drugs but over the dissemination of commercial drug information as well.

American physicians were deluged with pharmaceutical promotional materials. In 1958 the industry estimated that it had turned out 3,790,809,000 pages of paid advertising in medical journals, sent out 741,213,700 pieces of direct mail, and made up to 20 million calls by detail men to physicians and pharmacists (Harris 1964). The following passage from a study of detailing conducted in the early 1960s reveals physicians' reliance on detail men for information and the importance of personal relationships to the promotion of prescription drugs:

With growing competition from similar or virtually identical products manufactured by different companies, the importance of favorable interpersonal relationships has become increasingly important. … This inference was underscored by the study's finding that 45 percent of the physicians indicated that a “good” detail man was more like a friend than a salesman.

(Rehder 1965, 287–88)

The requirement that consumers obtain a prescription for most drugs came at a time when the medical profession was rising to a level of unprecedented autonomy and respect in American society (Starr 1982). Changes in medical education (e.g., establishing medical schools within universities, inserting a rigorous science base into the curriculum, and linking knowledge from laboratories to clinical practice) and scientific advances in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases increased the authority of medical professionals (Pescosolido and Martin 2004; Starr 1982). Physicians were given total control over medical training, medical decisions, and the ethical conduct of medical professionals (Pescosolido and Martin 2004).

The fact that pharmaceutical companies did not advertise prescription drugs to the public was consistent with the prevailing perception that patients were unable to make medical decisions on their own. After World War II, laypersons deferred to professional judgment to treat conditions that they previously would have treated by themselves. Social scientists writing about health care in the 1950s and 1960s portrayed medical consumers (referred to at the time solely as patients) as having little involvement in their health care, with sociologists describing them as “dependent: needing and expecting to be taken care of by stronger, more ‘adequate’ persons” (Parsons and Fox 1952, 32). Economist Kenneth Arrow (1963) portrayed the consumer of health care as uninformed and reliant on physicians to act as agents on his or her behalf. A major premise of Arrow's work was that health care markets were different primarily because of the asymmetry of information between physicians and their patients. Indeed, during this period, it was a common and accepted practice for physicians to withhold basic information from patients about their diagnosis and treatment (Rothman 1991).

Expanded Federal Regulation of Prescription Drugs

When Congress expanded the federal government's regulatory authority over drugs in 1938 and 1951, it did not give the FDA authority over either over-the-counter or prescription drug advertising, because when it passed the Wheeler Lea Act in 1938, it gave jurisdiction over drug advertising to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Moreover, because physicians were deemed capable of evaluating the accuracy of drug advertising, ads in medical journals were specifically exempted from the FTC's regulatory authority (Chadduck 1972). So even though the FDA tried to regulate advertising through the FDCA's labeling provisions, its authority was limited. For example, the FDA regulated direct mail ads to doctors but not advertising in medical journals.

In 1959 pharmaceutical marketing practices became the focus of congressional hearings, in response to prescription drug advertisements aimed at physicians that made efficacy claims for which no evidence existed and rarely mentioned side effects. For example, ads for diabinese (chlorpropamide), an oral antidiabetic introduced by Chas. Pfizer & Co., Inc., in 1958, claimed an “almost complete absence of unfavorable side effects,” despite a report prepared for the company showing a 27 percent incidence of serious side effects, including jaundice (Ruge 1969). In addition, many observers argued that physicians were incapable of deciphering truth from fiction in drug advertisements (May 1961).

In the early 1960s, the serious birth defects resulting from the use of thalidomide in Europe hastened Congress's efforts to overhaul federal drug regulation. In 1962, it passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the FDCA, which dramatically expanded the FDA's authority over prescription drugs by requiring that they be proved not only safe but also effective before being marketed. In order to receive FDA approval, the amendments also required drugs to meet a high standard of scientific evidence and transferred jurisdiction over the advertising of prescription drugs from the FTC to the FDA. In response to concerns for patients' safety and the misleading marketing practices of the 1950s, the FDA took a more proactive approach to regulating the advertising of prescription drugs than the FTC had (Terzian 1999). The FDCA's prescription drug–advertising provisions are relatively uncomplicated: they require prescription drug advertisements to contain the drug's established (or generic) name, the formula showing each ingredient, and a brief summary of the side effects, contraindications, and effectiveness. The detailed requirements for this summary were to be spelled out in regulations. In 1969 the FDA promulgated its final advertising regulations, which required advertisements to present a “true statement of information in brief summary relating to side effects, contraindications, and effectiveness” (FDA/DHHS 1969). Prescription drug advertisements also must present a “fair balance” between information about the drug's side effects and contraindications and information about its effectiveness. The regulations also describe how an advertisement could be considered false, unbalanced, or otherwise misleading.

Although the 1969 regulations did not mention prescription drug ads to the public, they contained two important provisions that later became relevant to DTCA. First, the regulations stated that advertisements broadcast through media such as radio, television, or telephone communications systems

shall include information relating to the major side effects and contraindications of the advertised drugs in the audio or audio and visual parts of the presentation, and unless adequate provision is made for dissemination of the approved or permitted package labeling in connection with the broadcast presentation, shall contain a brief summary of all necessary information related to side effects and contraindications. (italics added)

The meaning of “adequate provision” was unclear until 1997, when the FDA suggested ways in which pharmaceutical advertisements could meet the regulatory requirements, thus opening the door to broadcast DTCA. Second, the advertising regulations exempted some types of advertisements from the requirements. “Reminder advertisements,” which were designed for medical journals, contained only the name of the drug, and made “no claims for the therapeutic safety or effectiveness of the drug,” were specifically exempted from the FDA's requirements regarding the brief summary and fair balance of risks and benefits. Ads lacking a proprietary drug name also were exempted from the regulations. In the early 1990s, in order to circumvent the brief summary requirement, pharmaceutical manufacturers ran reminder ads and help-seeking ads that mentioned a disease or the name of a drug, but not both.

Informing the Patient

The FDA's authority over prescription drug advertising expanded during a time in which physicians had nearly complete control over medical practice and in which prescription drug advertising directed at the public did not exist. Rather, the advertising regulations were passed at a time when FDA officials were worried about patients' self-medication (Merrill 1973). But when the FDA tried to give consumers more information about prescription drugs by requiring special labeling for patients, they touched off a debate about the extent to which patients should be informed of the risks of taking a drug. In 1968, the FDA required the manufacturers of isoproterenol inhalers to provide a two-sentence warning on the package regarding a potential effect from excessive use of the inhalers (33 Federal Register 8812 [1968] codified at 21 C.F.R. § 201.305). In the 1970s the FDA also mandated a brief information leaflet for oral contraceptives (35 Federal Register [1970] codified at 21 C.F.R. § 310.501) and a few other drugs and devices.

The FDA also considered requiring patient package inserts (PPIs) on a widespread basis, owing in part to demands from the growing number of consumer groups (IOM 1979). Newly organized consumer groups such as the Health Research Group, formed under the auspices of Ralph Nader's Public Citizen, urged the FDA to make available to consumers more information about the risks of prescription drugs. In 1975 several consumer organizations filed a petition with the FDA requesting that the agency require patient labeling for prescription drugs because of their concern that doctor-patient communication about drugs was inadequate (IOM 1979). After conducting its own research in the 1970s, the FDA likewise determined that physicians were not adequately informing consumers of the risks of prescription drugs and hoped that through the patient package inserts dispensed with the drugs, consumers would be better equipped to use prescription drugs more safely (Kendellen 1985; Morris 1977). The broadening of the PPI initiative from a limited requirement for a few classes of drugs between 1968 and 1970 to a broader consumer education initiative in the late 1970s reflected the change in the FDA's views regarding the need to inform patients about prescription drugs (IOM 1979).

In 1976 and in 1978, the FDA sponsored two symposia to solicit feedback on the PPI concept from consumer groups, professional societies, pharmaceutical manufacturers, pharmacist organizations, and other groups. Two arguments were offered in support of the PPI concept. The first pertained to making the use of drugs safer and more effective. The argument was that PPIs would help improve patients' compliance and reduce drug interactions and adverse drug events by ensuring that they used prescription drugs properly. The second argument justified PPIs on the basis of patients' rights to information relevant to decisions about their medical care. This idea, rooted in the values of egalitarianism and patients' autonomy, assumed that PPIs would enable patients to assume a greater role in medical decision making (IOM 1979). Some observers of the debate over PPIs viewed these two lines of argument as conflicting, because the purpose of educating patients was better communication and cooperation, whereas the notion of patients' rights created confrontation (Albert Jonsen, cited in IOM 1979).

In the late 1970s the FDA proposed a regulation that would eventually require PPIs for all prescription drugs, an action that was resisted by the pharmaceutical industry because of the PPI program's cost (Schmidt 1985). In 1979 the agency issued regulations requiring the inserts for ten classes of prescription drugs. In 1982, after the Reagan administration appointed a new commissioner to the FDA, it rescinded the 1979 regulation in favor of a plan under which pharmaceutical companies would voluntarily disseminate information on prescription drugs to consumers (Pines 1999).

The FDA's policy on patient package inserts during the 1970s provides an important backdrop for subsequent debates over DTCA and the role of consumers in prescription drug markets (Pines 1999). Some physicians' groups and the pharmaceutical industry vehemently opposed the mandatory PPIs and echoed a familiar theme of health reform debates: that PPIs interfered with the doctor-patient relationship and represented the government's intrusion into the practice of medicine (Kendellen 1985). But the effort to require PPIs, albeit unsuccessful, showed that consumer groups' efforts to improve product safety in other areas of the economy could be applied to health care as well. Indeed, the Health Research Group became one of the most vocal critics of the pharmaceutical industry, its marketing practices, and DTCA.

The juxtaposition of the debates over PPIs and DTCA reveals that the stakeholders in the FDA's regulation of prescription drugs had somewhat nuanced views regarding patient information and education. On the one hand, pharmaceutical manufacturers objected to patients' rights to information regarding mandatory PPIs but supported them regarding looser restrictions on DTCA. On the other hand, consumer groups like the Health Research Group supported PPIs as a way to give consumers a greater role in decisions about their treatment, although this same group later opposed efforts to loosen restrictions on DTCA.

Dawn of the Patients' Rights Movement

The 1970s also marked the beginning of the patients' rights movement, which sought certain legal protections for patients, in response to cases of abuse of human biomedical research subjects publicized in the 1960s (Katz 1972). In the 1970s, this movement expanded from research subjects to patients. In 1975, Karen Ann Quinlan, age twenty-one, fell into an unexplained coma and remained in a persistent vegetative state and on a respirator for several months. When Quinlan's father signed a release to permit her doctors to turn off the respirator, they refused. The medical consensus at the time of the Quinlan decision was that the traditional relationship among the physician, patient, and family should prevail over a detailed legal standard (Clark and Agrest 1975). But this case and others that followed imposed a formality on medical decisions (Rothman 1991). Ethics committees, a feature of most hospitals today, were first recommended after the New Jersey Supreme Court handed down the Quinlan decision (Stevens 1996).

The Quinlan case helped spur the “right to die” movement that emphasized patients' autonomy in medical decision making. A review of public opinion surveys on death and dying conducted between 1950 and 1995 found a dramatic change in the public's attitudes toward personal control over the quality of life and death. In 1950, only 34 percent of Americans thought physicians should be allowed to end the lives of patients with incurable diseases if they and their families requested it, but by 1977, this figure had risen to 60 percent and has remained stable since then (Blendon, Szalay, and Knox 1992). While physicians still maintained a great deal of control over medical care, the patients' rights movement led the public to question medical authority and created intermediaries to oversee doctors' actions (e.g., ethics committees).

Early DTC Campaigns

The debate over PPIs during the late 1970s raised the issue of consumers' awareness of prescription drugs, their uses, and their risks. In the early 1980s, some pharmaceutical marketers began rethinking the traditional models of promotion that relied solely on advertising to physicians. They began first with public relations techniques rather than paid advertising (Pines 1999). For example, soon after Syntex, an analgesic, was introduced in the United Kingdom in 1978, it became a topic of discussion on talk shows and its use quickly accelerated. As a result, some pharmaceutical companies began considering the risks and benefits of communicating directly with the public about their products (Smeeding 1990). Pfizer launched a public relations campaign in the early 1980s called Partners in Health Care, to increase awareness of underdiagnosed conditions such as diabetes, angina, arthritis, and hypertension. Although the ads did not mention any drugs by name, they prominently displayed Pfizer's name in the hope that consumers who visited their doctors might ask for one of the manufacturer's products for those conditions.

From the 1950s to the early 1980s, no pharmaceutical companies were running product-specific ads in the mass media. Then, two product-marketing campaigns broke with tradition and pursued a marketing strategy that depended on consumers' taking a more active role in prescribing decisions. In 1981, Boots pharmaceuticals used print and television ads to promote Rufen, a prescription pain reliever. The marketing strategy was to position Rufen as a cheaper alternative to the leading brand. In 1982, Merck and Dohme advertised its pneumonia vaccine, Pneumovax, to people over the age of sixty-five, after market research showed that only a small percentage of the patients who could benefit from the vaccine were receiving it (U.S. House of Representatives 1984).

Early DTC campaigns demonstrated the role that consumers could play in health care, acting as price-conscious consumers or talking with their physicians about a condition that might otherwise not be detected. These early campaigns also demonstrated the potential harm associated with consumer-directed promotion. When it launched a new antiarthritic drug called Oraflex in 1982, Eli Lilly and Company distributed 6,500 press kits, including file films and videotapes, to television networks and radio stations (Kolata 1983). Although they dispensed some cautionary information, the media emphasized that Oraflex might prevent the progression of arthritis, a claim that went beyond the approved product label. The use of this drug, which may have been more widespread because of the public relations campaign, resulted in a number of adverse drug events, and it was pulled from the market voluntarily by Eli Lilly only five months after it was introduced (Basara 1992).

FDA Calls for Voluntary Moratorium on DTCA, 1983–1985

The FDA did not have an explicit policy regarding DTCA at the time of these early campaigns because there had been no mass media advertisements for prescription drugs when the 1969 regulations were promulgated. Initially, agency officials supported the concept of DTCA and had faith that the existing regulations for promotion to physicians would prevent any misleading advertisements directed at consumers (Altman 1982). But in 1983, the agency began to voice serious concerns about advertising prescription drugs to consumers. Commissioner Arthur Hull Hayes asked the pharmaceutical industry to stop advertising drugs to the public. Concerns raised at the time were that DTCA would

lead patients to pressure physicians to prescribe unnecessary or un-indicated drugs, increase the price of drugs, confuse patients by leading them to believe that some minor difference represents a major therapeutic advance, potentiate the use of brand name products rather than cheaper, but equivalent generic drugs and foster increased drug taking in an already overmedicated society.

(Morris et al. 1986b, 82)

Furthermore, FDA Commissioner Hayes also voiced concern about the public's ability to evaluate “the risk/benefit ratio of a drug” (Kolata 1983). The FDA undertook a study of consumer perceptions of and behavior related to prescription drug advertising and found that consumers wanted more drug information but that it was difficult to communicate risk information through short television ads (FDA 1983; Morris et al. 1986a, 1986b).

In September 1985, the FDA rescinded the moratorium on DTCA advertising and required the advertisements to meet the same legal requirements as those directed at physicians (FDA/DHHS 1985). Public comments by the FDA commissioner suggested that agency officials did not believe that a widespread use of DTCA would result (U.S. House of Representatives 1984). These advertising provisions of the 1969 regulations created a de facto barrier to the broadcast advertising of prescription drugs that included both the name of the drug and its indication, because it was not feasible to air the entire brief summary in a short television commercial, so the few DTCA campaigns initiated in the 1980s used print media. The brief summary of the product label had become something that was “neither brief nor a summary” but a densely worded compilation of every risk carried by the drug written in highly technical terms (Feather 1997).

Critical Views of DTCA

An analysis of interest-group positions on DTCA in the early 1980s shows significant resistance to greater consumer control over prescription drug use, by physicians' organizations, consumer groups, and even many in the pharmaceutical industry. One of the recurrent themes in the early debates over DTCA was its potential to undermine physician authority (Lanier 1982). Surveys by the AMA found that an overwhelming majority of physicians were opposed to DTCA on television (84 percent in 1984 and 81 percent in 1988 opposed DTCA on television) (Harvey and Shubat 1989). In the early 1980s, the AMA, the American Society of Internal Medicine, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Society of Internal Medicine, and the American College of Physicians and other groups took positions against the DTCA of prescription drugs (AMA 1989; Cohen 1988; U.S. House of Representatives 1984). A letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine said that DTCA “may tend to undermine physician control over prescribing” and that “most lay people are ill equipped to evaluate the efficacy or toxicity of drugs” (O'Brien 1982, 181).

Consumer groups also were firmly opposed to DTCA. Dr. Sidney Wolfe of the Health Research Group called for a ban on DTCA and renewed calls for patient package inserts (Consumer Reports 1984). Representatives from the Consumer Federation of America and the American Association for Retired Persons (AARP) also spoke out against DTCA in the 1980s (Kolata 1983). Survey research conducted at this time showed that consumers considered physicians the primary decision makers with regard to prescription drugs and viewed the patient's role in drug utilization and as an evaluator of prescription drug advertising as quite limited. More than three-quarters of consumers disagreed with the statement that they could decide about using a drug, and 63 percent disagreed with the statement that patients could tell whether a prescription drug ad was misleading (Morris and Millstein 1984). But surveys conducted by the FDA in the early 1980s also revealed that consumers wanted more information about prescription drugs (Morris et al. 1986b).

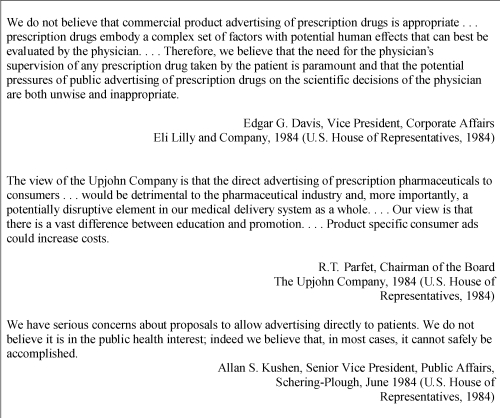

In the early 1980s most pharmaceutical companies avoided DTCA of prescription drugs, according to a survey conducted in 1984 of pharmaceutical marketing executives (Cutrer and Pleil 1991). When Representative John Dingell, chairman of a subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, sent a letter to several pharmaceutical company executives in 1984 asking for their views on DTCA, most of the responses were deeply critical of DTCA (see the excerpts of letters in Figure 1). Pharmaceutical executives argued that DTCA would hurt the doctor-patient relationship, confuse an unsophisticated public, and lead to higher drug costs. They thus recommended strict limits, if not an outright ban, on prescription drug advertising to the public. Their views indicate that in the early 1980s, the pharmaceutical industry wanted to work with rather than challenge the traditional doctor-patient relationship.

figure 1.

Source: U.S. House of Representatives 1984.

Excerpts from Letters from Pharmaceutical Executives to Committee Chairman John Dingell, 1984

Challenges to Physicians' Autonomy and the Increased Appeal of DTCA to the Pharmaceutical Industry

Around 1990, changes in the health care system and in the pharmaceutical industry itself led the pharmaceutical industry's opinion of DTCA to change as well. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, employers assumed more aggressive roles in reining in health care costs (Schlesinger 2002). Escalating health insurance premiums combined with an economic recession in the early 1990s forced employers to begin reconsidering the merits of traditional fee-for-service insurance reimbursement (Reinhardt 1999). Evidence revealed a substantial variation in health care utilization and spending and confirmed that high spending was not correlated with better treatment outcomes. Employers thus turned to managed care plans, which controlled health care spending through supply-side mechanisms such as requiring utilization reviews, capitating provider payments, and engaging in selective contracting with providers, all of which challenged physicians' autonomy (Schlesinger 2002).

At the same time, the American public had been losing trust in physicians since the 1960s, mirroring the general weakening of trust in authority figures and institutions (Blendon and Benson 2001; Pescosolido, Tuch, and Martin 2001). In 1966, three-quarters of the American public had a great deal of confidence in leaders in medicine, but in 1990, less than one-quarter did. Using survey data from policy elites and the general public, Schlesinger (2002) argued that the decline in trust was driven by doubts about the efficacy of medical care and questions about whether physicians were acting as good agents for their patients, particularly when a physician's economic interests and the patient's interest conflicted.

New Financial Imperatives

From the 1950s until the 1980s, pharmaceutical firms promoted their products by influencing a learned intermediary—the physician. Accordingly, when the autonomy of physicians over the practice of medicine was threatened by consumers' distrust and the growth of new institutions like managed care plans and hospital formulary committees, new forms of promotion emerged (Kessler and Pines 1990). In the late 1980s, some pharmaceutical manufacturers, wary a few years earlier of upsetting doctors by advertising directly to consumers, began to view DTCA as an integral part of their marketing strategy. In the early 1980s, a handful of drug marketers employed indirect public relations tools to get the word out to the public about new drugs. By the end of the decade, several pharmaceutical manufacturers used paid advertising in its most visible and direct form to promote prescription drugs to consumers. Between 1985 and 1990, pharmaceutical marketers launched DTCA campaigns to promote at least twenty-four products directly to consumers (Scott-Levin 1992). DTCA thus became part of a broader trend in the pharmaceutical industry toward more spending on all forms of promotion and more aggressive marketing techniques (Feather 1997; Smeeding 1990).

Another trend that may have accelerated the trend toward DTC promotion is that many of the top-selling drugs switched from prescription to over-the-counter (OTC) status. Prescription drugs that advertised to consumers would therefore have the advantage of established brand recognition before being converted to OTC status (Ling, Berndt, and Kyle 2003). In addition, the increased use of DTCA in the early 1990s may have been related to the introduction of “lifestyle” drugs for which no market yet existed. For example, it would have been difficult for Upjohn to convince physicians to talk with their male patients about the prescription drug Rogaine, a hair restoration product, through traditional forms of promotion such as detailing (Ruby and Montagne 1991). The very existence of products like Rogaine—products that focused more on improving the quality of life than on treating disease—illustrates the consumer's growing importance in medical care at the time. Indeed, drugs advertised to consumers continue to be those requiring consumers to self-identify, either because physicians feel uncomfortable discussing the product (e.g., drugs that treat erectile dysfunction) or because a need for the product might not be detected in a primary care setting (e.g., drugs that treat depression) (Iizuka 2004).

Consumerism in Health Care

In addition to reacting to changes within the industry, pharmaceutical firms capitalized on a significant cultural change in the health care system that accelerated in the late 1980s, one that emphasized the consumer's role in medical decision making. Efforts in the 1970s to secure legal rights for patients to be informed about their treatment options set the stage for efforts in the mid-1990s to secure consumer rights in managed care (Rothman 2001). By the late 1990s a more diffuse change made possible by advances in information technology allowed patients and consumers to inform themselves and, as a consequence, become more involved in medical decision making, what I call consumerism.

By the late 1990s, several reforms of the health care system had been implemented, including changes in involuntary commitment laws, consent forms for surgery and other medical procedures, and stricter controls over human experimentation (Tomes 2001). The Patient Self-Determination Act, passed in 1989, required health care institutions to advise patients upon admission of their right to accept or refuse medical care and to execute an advance directive (Laine and Davidoff 1996). And in 1996, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) ensured patients' rights to privacy over their medical records.

Consumerism in health care did not end with the establishment of legal rights for patients, however. This new consumer power also was evident in the increasing number and political influence of disease-specific advocacy groups. In 2000, there were more than 3,100 disease-specific advocacy groups with at least some political involvement, many of which had been founded in the 1980s (Baumgartner and Jones 1993; Carpenter 2004). In 1996, citizen groups and not-for-profit advocacy organizations outnumbered hospitals and clinics by a factor of two to one in terms of the number of groups lobbying federal policymakers on health care issues (Baumgartner and Leech 1996). Health activism coalesced around stigmatized social groups (e.g., the mentally ill), and were created from existing constituencies (e.g., women, gays, consumer advocates) (Halpern 2004). These groups were successful in lobbying for increased research funding for diseases like HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, and other conditions (Epstein 1996).

Consumer advocates also played an important role in the backlash against managed care (Peterson 1999). By the mid-1990s, managed care plans had gained a majority share in the private insurance market. In fact, state legislatures passed more than one thousand bills in the 1990s “regulating” managed care. The first wave of such legislation, led by providers, focused on removing plans' ability to use restrictive provider networks through “any willing provider” laws (Sorian and Feder 1999). But the emphasis soon shifted to consumers. Managed care regulation passed at the state level and debated at the federal level blended patient protections (e.g., length of stay requirements, benefit mandates) with consumer protections (e.g., insurance plan information disclosure and due process requirements) (Mariner 1998).

Important changes also were under way in the doctor-patient relationship through efforts to make medical care more “patient centered.” The editor of the New England Journal of Medicine wrote as early as 1983 that “physicians must set aside their image of themselves as making life and death decisions alone and undertake instead the less glamorous and more time-consuming process of exploring optimal outcomes with the patient” (Kassirer 1983, 900). Research on the impact of patients' adherence on clinical outcomes encouraged clinicians to abandon paternalistic approaches to patient care and adopt practice styles emphasizing the patient's participation in clinical decisions (Roter and Hall 1992).

A related trend was the greater use of complementary and alternative medicines (e.g., herbal medicine, vitamins and dietary supplements, chiropractics) in the 1990s. For example, the percentage of adults in the United States who used alternative medicine increased from 33.8 percent in 1990 to 42.1 percent in 1997 (Eisenberg et al. 1998) and remained stable between 1997 and 2002 (Tindle et al. 2005). Since the establishment of the AMA's first code of ethics, organized medicine had actively opposed alternative medicine (Kaptchuk and Miller 2005). But recently this opposition has given way to efforts to integrate alternative medicine into institutions of biomedicine, partly because of patients' demands for it. But in 1990 and 1997, less than 40 percent of the alternative therapies used were disclosed to a physician (Eisenberg et al. 1998), indicating that most consumers still viewed alternative medicine as self-treatment rather than a recommendation by their doctor.

Technological change also spurred an increase in health information seeking and self-treatment. In the mid-1990s, American society was at the start of a revolution in information technology that significantly expanded the number of consumers seeking health information and support from sources other than their physicians. By 2000, more than 26,000 websites were related to health, and roughly one-quarter of individuals using the Internet did so primarily to find information about health and health care (Haas-Wilson 2001). By March 2003, 66 percent of Internet users said they went online to look for health or other medical information (Fox and Fallows 2003). Surveys conducted in conjunction with the Pew Internet and American Life Project found that (1) people used the Internet to inform themselves about their health and carried that information with them to their doctors and that (2) when they presented this information to their doctors, they sometimes encountered resistance (Fox and Fallows 2003). As one consumer who responded to the survey summarized, “Knowledge is power. It also helps me to feel prepared to talk with doctors and nurses. I know the terminology and the options” (Fox and Fallows 2003, 16).

The convergence of these trends increased the amount of information available to consumers and their level of involvement in medical decision making. The expanding rights of patients, along with the more diffuse trend toward consumerism in health care, thereby made less salient any criticism of DTCA, often couched in terms of traditional norms of medical practice that emphasized physicians' authority.

Pressure on the FDA to Loosen Restrictions on Advertising

Pharmaceutical industry spending on DTCA rose from $55 million in 1991 to $363 million in 1995, reflecting the industry's calculation that the profits earned from pitching products directly to patients outweighed any loss of goodwill from a profession that for decades it had relied on to promote its products. This greater use of DTCA came at a time when the FDA was more actively enforcing advertising regulations and restricting new forms of promotion like video news releases, discussions of drug development with the investment community, and DTCA (Kessler and Pines 1990).

In November 1990, President George H.W. Bush appointed David Kessler (both a physician and an attorney) as the head of the FDA. Kessler became one of the most active FDA commissioners in modern times. He tried to expand the FDA's authority to regulate the health claims made for dietary supplements and to regulate tobacco as a drug, but both efforts met with substantial political resistance and ultimately failed (Hilts 2003). Kessler was particularly interested in reining in prescription drug marketing, and he increased the resources devoted to the FDA division that oversees drug advertising (Kessler et al. 1994; Kessler and Pines 1990).

Significant counterregulatory pressures during the mid-1990s moderated the efforts to restrict drug promotion (Epstein 1996; Hilts 2003). In 1994, with the Republican Party's takeover of Congress, the FDA encountered conservative opposition on many fronts. House Speaker Newt Gingrich called the FDA the “no. 1 job killer,” charging that it discouraged innovation and prevented profitable products from coming to market (Hilts 2003, 196). Conservatives also charged that the FDA's new drug approval process placed so much emphasis on keeping potentially bad drugs off the market that it unnecessarily delayed the introduction of important therapeutic advances. This criticism was echoed by a new and vocal breed of consumer advocacy organization that urged the FDA to reconsider its standards for approving drugs to combat HIV/AIDS (Epstein 1996). A parallel criticism was leveled against the FDA's approach to regulating drug advertising. Some argued that the FDA was so heavily focused on prohibiting misleading advertising that it prevented valuable information about prescription drugs from reaching consumers and physicians (Keith 1992).

In this environment of greater consumer involvement in health care, increased spending on consumer-directed promotion of prescription drugs, and scrutiny of the FDA's regulation of advertising, the agency held hearings on DTCA (FDA/DHHS 1995b). Officials heard testimony from pharmaceutical and advertising industry representatives, consumer organizations, medical societies, and academics. The pharmaceutical industry sought clarification of the provision in the 1969 advertising regulations that obviated the need for broadcast advertisements to contain the brief summary of the approved product label when “adequate provision” was made for dissemination of the product labeling in conjunction with the advertisement (FDA/DHHS 1969). In 1995, roughly 15 percent of DTCA spending was for television advertising (Kreling, Mott, and Wiederholt 2001). In order to circumvent the brief summary requirement, pharmaceutical companies ran reminder or help-seeking advertisements, which either included the name of the drug or discussed a particular condition, but not both. Reminder ads, which were originally designed for physicians and medical journals, led to some confusion among consumers who did not know what condition the drug was supposed to treat.

Some people who testified at the hearings noted that consumers' involvement in health care had expanded dramatically since the first DTC ads were aired in the early 1980s (FDA/DHHS 1995a). Participants in the hearings pointed to two divergent approaches to communicating risk information to consumers. Advocates of the first model proposed by critics of DTCA believed that the best method of educating consumers about prescription drugs was through something akin to patient package inserts. This model assumed that consumers needed to be educated after the prescribing decision had been made and that the package insert would help make the product safer. Consumer groups like the Health Research Group, which focused on product safety, adhered to this view.

The other model of information dissemination, supported by representatives of the advertising and pharmaceutical industries, proposed replacing the brief summary with a general risk statement like “prescription drugs could be harmful to your health and should not be taken without consulting a physician.” Advocates of this view considered advertising as a way to get the consumer—not the physician—to initiate the conversation about a prescription drug and so wanted to give consumers information about a drug well before the prescribing and purchasing decisions were made. The brief summary requirement was therefore seen as a barrier to direct communication between the pharmaceutical manufacturer and the consumer.

By 1997, those FDA officials who were reluctant to open the floodgates to prescription drug advertising on television felt increased pressure from a variety of sources to ease the regulations and permit broadcast advertising (Feather 1997). In August, a few months after David Kessler left the FDA, the agency released the Draft Guidance for Industry: Consumer-Directed Broadcast Advertisements. It outlined the ways in which pharmaceutical manufacturers could meet the brief summary requirement in broadcast ads by clarifying the ways in which the product labeling could be adequately provided (FDA/DHHS 1997, 1999). Instead of airing the entire brief summary, the ads could refer consumers to (1) a toll-free telephone number, (2) print ads, (3) a website, and/or (4) their pharmacists or physicians, from whom they could obtain complete information about the product's risks and benefits. Consumers' confusion over the reminder ads for prescription drugs on television was a major factor behind the policy change (Woodcock 2003). Although whether the guidance was intended to loosen restrictions or to clarify existing provisions of advertising regulation has been debated, it nonetheless made broadcast advertisements of prescription drugs more feasible.

Contemporary Views of DTCA

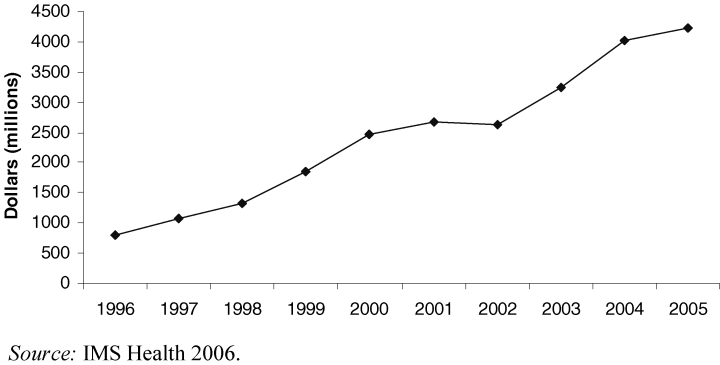

The pharmaceutical industry quickly seized on the policy change, more than doubling its spending on television advertising from $310 million to $664 million between 1997 and 1998, with the total spending on DTCA advertising rising from $1.3 billion in 1998 to $3.3 billion in 2005 (Figure 2). Pharmaceutical firms, which a little more than a decade earlier had feared the impact of DTCA on the doctor-patient relationship, now argued that prescription drug advertising empowered consumers. The president of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America stated, “Direct-to-consumer advertising is an excellent way to meet the growing demand for medical information, empowering consumers by educating them about health conditions and possible treatments” (Holmer 1999, 380). The majority of spending on DTCA since the policy change has been for television advertising, and more than 80 percent of prescription drug ads in the 1990s promoted specific products rather than raising awareness of medical conditions.

figure 2.

Total U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry Spending on DTCA 1996–2005

In 1992, the AMA recognized consumers' more assertive role in their health care and altered its policy to support DTCA on a limited basis when such ads were in the patient's best interest and conformed to guidelines established by the FDA and the AMA (Borow 1993). But following the release of the draft guidance in 1997, the AMA sent a letter to the FDA expressing its concern about the potentially adverse impact of DTCA on the physician-patient relationship and the potentially negative public health and economic outcomes (Neilsen 2003). In 1999, the AMA established standards for appropriate consumer-directed advertisements. They state that DTC advertisements should focus on diseases rather than specific products and also that physicians should be concerned about advertisements, which “do not refer patients to their physicians for more information, and do not identify the consumer population at risk by implying self-diagnosis and self-treatment” (AMA 2000, 122). The AMA's rather ambivalent policy on DTCA highlights the difficult balance between supporting consumers' involvement in health care and maintaining control over medical decision making.

Recent surveys of physicians indicate that even though many still oppose the practice of DTCA in general, they also point to some positive effects. A survey of family physicians in 1997 found that 80 percent of physicians believed DTCA was not a good idea (Lipsky and Taylor 1997). More recently, however, in a 2002 survey of physicians conducted by the FDA, only 18 percent believed that DTC created problems with their interaction with a patient, and 41 percent said that DTC had beneficial effects on the interaction (Swasy 2003). These findings contrast with the nearly universal opposition to DTCA expressed in surveys of physicians in the 1980s.

Some consumer groups reacted negatively to the 1997 draft guidance for broadcast advertising (Sasich and Wolfe 1997). For example, the Health Research Group (HRG) argued that a sixty-second television commercial would not be adequate to convey risk information to consumers and that the FDA's policy left “consumers naked in the viciously competitive marketplace for prescription drugs” (Sasich and Wolfe 1997, 1). The group called for a moratorium on DTCA until the FDA could issue regulations specifically governing consumer-directed advertisements. In an editorial, HRG's director acknowledged consumers' desire for more information but differentiated between drug information provided for educational purposes and advertising:

During the past two decades, there has been an irreversible change in the nature of the doctor-patient relationship. Patients are seeking much more medical information and are actively participating in decisions affecting their health. Intruding into this trend has been the rise of direct-to-consumer promotion, which in its initial thrust, bypasses primary care doctors and other physicians. Although increased access by patients to accurate, objective information about tests to diagnose and drugs to treat illnesses is an important advance, confusion arises when commercially driven promotional information is represented as educational.

(Wolfe 2002, 524)

Other consumer groups, however, expressed more positive views about DTCA. After it held a roundtable on DTCA, the National Consumers League concluded that it was “an effective vehicle that motivates consumers to seek information, especially from health care professionals” (National Consumers League 1998). Its 2003 press release noted that “critics attack such ads for provoking patients to ask their doctors for expensive drugs for which they may not have a medical need. But if these ads are encouraging dialogue of any nature between doctors and their patients, this can hardly be a bad thing” (National Consumers League 2003).

Surveys suggest that DTCA affects consumers' behavior (Slaughter 2002/2003). In 2002, 98 percent of Americans reported that they had seen or heard an ad for prescription drugs. Of those who had seen an ad, 33 percent talked to their physician about the medicine. Thirty percent (or about 8 percent of total) of those who talked to their doctor asked for a prescription, and 79 percent of those who asked for a prescription (or about 5 percent of all Americans) had their request honored. Another survey found that roughly half of consumers who talked to their physician after seeing a DTCA ad were seeking treatment for the condition for the first time (Weissman et al. 2003). Moreover, surveys show that most consumers view DTC ads positively. Only one-quarter of consumers surveyed in 2002 believed that prescription drug ads should be limited to medical journals read by physicians (National Consumers League 2003).

A few years after the draft guidance FDA Commissioner Jane Henney, citing a survey conducted by the FDA, wrote that “DTC prescription drug promotion offers public health benefits that may outweigh potential costs” (Henney 2000, 2242). In a few short years, the agency changed its view of DTCA from being wary of “opening the floodgates” to television advertising to seeing a public health benefit from this form of promotion. This marks a dramatic shift in the view of DTCA among regulators trying to balance the traditional emphasis on preventing misleading advertising with the goal of providing consumers with more information about possible treatments. Even former FDA Commissioner David Kessler, who had opposed loosening the regulations to allow broadcast advertising throughout his term in office, recently recanted (Mishra 2002). Moreover, the director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research spoke at a public meeting on DTCA sponsored by the FDA on the relationship between DTCA and consumerism (Woodcock 2003, 18–19):

It was not until the time of HIV and cancer activism in the late 1980s that the concept of patient empowerment really took hold. And I think it is no coincidence that around that time we began to see, again, reemergence in the interest … in direct-to-consumer advertising. Several other forces were also active at that time. First, outcomes researchers had shown that patient values and preferences could drive the choice of appropriate treatment. … Second, the rise of managed care in many forms led patients to believe that the health care system could not always be completely relied upon to act in their best interest at all times. These forces have resulted in a shift in the general societal perception of who needs what information. And of the dynamics of medical decision making in general.

Conclusion

The last few decades have seen a dramatic transformation of the consumer's role in health care, and DTCA and the policy debate surrounding it relate directly to this transformation. The current period of consumer involvement in health care harkens back to the drug market in the early twentieth century when self-treatment was highly valued and most drug advertising was aimed directly at consumers. Physicians' authority over the prescribing of drugs has been directly challenged by DTC advertising campaigns urging consumers both to self-diagnose and to demand specific medications from their provider. We therefore are not likely to return to the days when consumers were effectively cut off from commercial information about prescription drugs, nor are pharmaceutical companies likely to abandon their focus on physicians, who still control access to prescription drugs.

By 2004, DTCA seemed to have weathered the deluge of criticism it encountered in the late 1990s. But Merck's withdrawal of Vioxx from the market renewed criticism of DTCA, and in 2005 the U.S. Senate majority leader, William Frist (a physician), called for a two-year voluntary moratorium on the use of DTCA for newly approved drugs (Saul 2005). In June 2005, Bristol Myers Squibb announced a one-year moratorium on DTCA for new product launches, and in 2004, Pfizer announced a voluntary moratorium on DTCA for Celebrex, its COX-2 inhibitor. In addition, the FDA is continuing its decades-long effort to improve the communication of drug risks and benefits to consumers. Because the FDA's authority is limited to approving drugs and it cannot decide the price purchasers will pay (as similar agencies in other countries can), the policy debate over DTCA is mostly limited to its effect on drugs' safety and effectiveness. The impact of DTCA, and related trends in medical consumerism, on health care costs receives less attention.

The history of consumerism and DTCA has important implications for other contemporary health policy debates. The first is that as bioethics historian David Rothman (2001, 261) wrote, “When commerce joins with ideology, we have a powerful engine for promoting change.” The pharmaceutical industry not only reacted to the trend toward consumer-oriented medicine but also reinforced this cultural shift with an onslaught of mass media advertising. The industry defined DTCA as a tool to enhance consumer choice and autonomy. Similarly, the industry has argued for consumer choice in prescription drug coverage policy in public insurance programs. Some state Medicaid policymakers have been reluctant to restrict access to costly psychotropic medications, in part because of vocal opposition from mental health consumer advocacy organizations. Borrowing the language of consumer empowerment and choice, pharmaceutical manufacturers, which have a clear financial incentive to remove any restrictions on the use of their products, have supported mental health consumer groups in opposing cost-control mechanisms (Harris 2003). But the industries' funding of consumer groups' advocacy efforts have called into question the authenticity of the consumers' perspective (Tomes 2006). Long-standing skepticism of medical research financed by the pharmaceutical industry has been joined by concerns about alliances between the pharmaceutical industry and consumer advocacy groups. Ethical issues surrounding these alliances have received less attention in the literature.

The image of consumers as highly educated, technology savvy, and assertive strongly influences the current reshaping of health insurance arrangements in the public and private sectors. In the last few years, the health insurance industry has adopted new benefit, network, medical management, and pricing policies in response to the demand from employers. These contemporary policies highlight the insurers' shift away from cost containment through supply-side mechanisms that try to influence physicians' behavior in favor of policies that focus on the consumer side of the health care market (Robinson 2004). Arguments in favor of shifting entitlement programs and employment-based health insurance away from defined benefit plans toward the use of medical savings account models will be more salient when accompanied by descriptions of informed consumers. Indeed, the term defined contribution health plan has been replaced with consumer-driven health care plan, implying that consumers exert considerable control over their insurance arrangements (Shearer 2004). Health plans and purchasers are relying less on supply-side cost control mechanisms like restrictive provider networks and are focusing more on altering consumers' behavior, arming them with information (at least in theory) and stronger financial incentives to make prudent purchasing decisions. The rhetoric of consumerism no doubt contributed to this transformation of the health insurance market.

Legal and cultural changes in health care brought about by the patients' and consumers' rights movements laid the groundwork for the DTCA of prescription drugs. DTCA was surely an unintended consequence of these social movements and may, paradoxically, serve to frustrate future efforts to protect patients and consumers. That is, by shifting the rights and responsibilities for financing health care from government and private purchasers toward individual consumers, we are reducing the opportunities for public discourse on what health services should be covered and for whom (Robinson 2005). Collective decisions about health care priority setting are being replaced by private health care choices. Interestingly, countries with national health systems that delegate technology assessment and priority setting to governments have chosen not to allow the DTCA of prescription drugs. In 2002, the European Parliament voted 494 to 42 to reject a proposal to allow DTCA. European consumer groups contended that allowing DTCA would “lead to a US-style spiral of unsustainable health care spending” (HAI/EPHA 2002). By arming consumers with more information about newer, more expensive treatments, the DTCA of prescription drugs and similar marketing efforts will likely foster continued resistance to centralized cost containment methods that explicitly limit the choices of consumers.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Allan Brandt and Patricia Keenan for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article. In addition, I would like to thank Bradford Gray and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. All errors are my own.

Endnotes

The economic literature does not agree on whether advertising serves to inform consumers, thereby improving the performance of the market, or to persuade consumers by altering their preferences, thereby undermining competition. For a discussion of these issues, see Hurwitz and Caves 1988.

Narcotic drugs were a notable exception. Before federal drug regulation, some states required consumers to obtain prescriptions for narcotics or poisons. In 1914, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Act, which required consumers to obtain a prescription for narcotic drugs, but most other classes of drugs did not require a prescription until after 1951.

Advertisement in an 1881 Salt Lake City newspaper obtained from Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health. See http://www.mum.org/MrsPink1.htm.

References

- Altman LK. Prescription Drugs Are Advertised to Patients, Breaking with Tradition. New York Times. 1982:C1. February 23. [Google Scholar]