Abstract

Working-age people with disabilities are much more likely than people without disabilities to live in poverty and not be employed or have shared in the economic prosperity of the late 1990s. Today's disability policies, which remain rooted in paternalism, create a “poverty trap” that recent reforms have not resolved. This discouraging situation will continue unless broad, systemic reforms promoting economic self-sufficiency are implemented, in line with more modern thinking about disability. Indeed, the implementation of such reforms may be the only way to protect people with disabilities from the probable loss of benefits if the federal government cuts funding for entitlement programs. This article suggests some principles to guide reforms and encourage debate and asks whether such comprehensive reforms can be successfully designed and implemented.

Keywords: Disability, poverty, employment, policy

Working-age Americans with disabilities are much more likely to live in poverty than other Americans are, and most did not share in the economic prosperity of the late 1990s. At the same time, public expenditures to support working-age Americans with disabilities are growing at a rate that will be difficult to sustain when the baby boom generation retires and begins to draw Social Security Retirement and Medicare benefits. We suggest that better policies would both improve the lives of many people with disabilities and stimulate the labor supply of working-age people with disabilities at a time when labor is becoming an increasingly scarce resource. Accordingly, the current policies that trap people with disabilities in poverty and encourage them to retire early even when they still may have some work capacity should be replaced with policies that reflect twenty-first-century realities.

More specifically, we argue that some current policies are outdated and paternalistic and should be replaced by policies promoting economic self-sufficiency and bringing the relevant programs in line with more modern thinking about disability. Indeed, today's paternalistic policies trap many people with disabilities in poverty by devaluing their often considerable ability to contribute to their own support through work. Although recent reforms are an improvement, they do not adequately promote true economic self-sufficiency. Rather, they should take advantage of the productive capacities of people with disabilities while at the same time providing sufficient support to ensure that those who are working will achieve a higher standard of living than they can under the current policies. Such policies would

Take advantage of the advances in medicine, technology, training, and workplace modifications that enable many people with significant physical or mental impairments to work.

Be consistent with changes in the social expectations for people with disabilities and for the workplace improvements embodied in the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Increase public support for disability programs and reduce the vulnerability of people with disabilities to future program cuts.

Motivate and empower people with disabilities to participate more fully in the economic mainstream.

Address unrealistically low societal expectations about the work capacity of people with disabilities.

The transition to economic self-sufficiency policy has already begun, with several important pieces of legislation and other initiatives that reflect a more modern approach to disability policy. We argue, however, that these changes alone are inadequate to achieve the ambitious objectives of advocates and policymakers. More radical change is needed, and many difficult challenges remain to be addressed. Leaders in business and government must recognize that this is an urgent issue for the country's entire economy, not just an issue of providing more appropriate support for people with disabilities.

Employment and Poverty of People with Disabilities: A Discouraging Picture

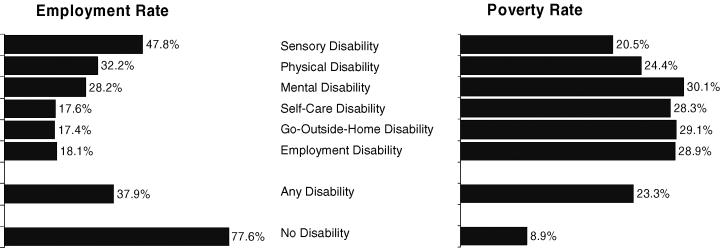

The employment rate of working-age people with disabilities is well below that of their nondisabled cohort, regardless of what national survey is used or how disability is measured. The American Community Survey (ACS) is a survey by the U.S. Census Bureau designed to replace the decennial census long form. Starting in 2000, the ACS has contained six measures of disability: sensory, physical, mental, self care, ability to go outside the home, and employment. Based on these measures, 38 percent of working-age people with at least one of the ACS disabilities were employed in 2003, compared with 78 percent of people reporting none of the ACS disabilities (left panel of Figure 1). The low employment rates of people with disabilities are reflected in their poverty rates, which for people with at least one disability are more than twice as high as for those with no disabilities (right panel of Figure 1). Many others live in families with incomes just above the official federal poverty standard, which does not allow for the extraordinary disability-related expenses incurred by many people with disabilities.

figure 1.

Employment and Poverty Rates by Disability Status, 2003

Source: R. Weathers, A User Guide to Disability Statistics from the American Community Survey (Ithaca, N.Y.: Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Disability and Demographic Statistics, Cornell University, 2004).

These poverty rates are high, even though almost 9 million working-age adults with disabilities receive income support from the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs. Although the SSI and SSDI programs have provided cash assistance to millions of Americans since their inception, these benefits often are not enough to lift incomes above the poverty standard. Indeed, the maximum federal SSI benefit now is only about 75 percent of the federal poverty standard for an individual. In addition, many people with disabilities do not receive support from these programs. In 2002, 41.6 percent of working-age adults with any ACS disability who lived in a household with an income below the poverty line received income support from SSDI and/or SSI. Another 6.8 percent lived in a household whose income was from the federal/state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program (Weathers 2004). In many areas, the basic SSI monthly benefit is not sufficient to pay for housing; for example, in 2002, the average national rent for a modest one-bedroom apartment was 105 percent of the SSI monthly benefit amount (O'Hara and Cooper 2003).

Although the country's recent economic growth has somewhat reduced the poverty rate of people without disabilities, it has not helped people with disabilities (Burkhauser, Daly, and Houtenville 2001; Burkhauser, Houtenville, and Wittenburg 2003; Burkhauser, Houtenville, and Rovba 2004; Burkhauser and Stapleton 2003, 2004a). For example, the poverty rates that Burkhauser, Houtenville, and Rovba (2004) report for working-age adults with “long-term” work limitations (i.e., work limitations reported in each of two surveys, twelve months apart) are comparable in magnitude to the ACS poverty rate estimates. When comparing the two surveys conducted during the business cycle peak in 1989 with the two surveys conducted during the business cycle peak of 2001, they found that the poverty rate had risen from 26.9 percent in 1989 to 27.6 percent in 2000, compared with a decline from 7.1 percent to 6.5 percent for those without work limitations.

Unprecedented Growth of Dependence on Public Programs

The decline in the economic status of people with disabilities despite higher public expenditures has outpaced economic growth. In FY2002, the federal government spent $87.3 billion on SSI and SSDI benefits and another $82.1 billion on Medicare and Medicaid programs for working-age people with disabilities. Adding federal expenditures for housing, food assistance, rehabilitation, income assistance for families, assistance for veterans, and other programs for people with disabilities brings the total federal spending to approximately $226 billion: 11.3 percent of total federal outlays in FY2002 and 2.2 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP).

From FY1986 to FY2002, federal disability expenditures grew 85 percent more than total federal outlays and 57 percent more than the growth rate of the GDP. In FY2002 the state governments contributed an additional $44.6 billion under Medicaid and $2.9 billion for state supplements to SSI (Goodman and Stapleton 2005). In sum, expenditures are growing faster than federal outlays and GDP because of the rapid growth in the number of people with disabilities receiving income and health care support, along with the rising cost of health care. Although one reason for the growing number receiving benefits is the aging of the baby boom generation, another important reason is the higher participation rate for almost every age group.

The single most important component in the growth of federal disability expenditures is the greater number of people on the SSDI rolls, all of whom also are enrolled in Medicare after a twenty-four-month waiting period. One recent study estimates that the fraction of the working-age population on the SSDI rolls rose by 76 percent from 1984 to 2003 (Duggan and Imberman 2006). Although the authors trace some of this to the aging of the baby boom generation and the long-term growth of female labor force participation, they attribute the bulk of the growth (82 percent for men and 72 percent for women) to program policies and how they interact with the economy. They note a 48 percent rise in the number of nonelderly adult DI recipients from December 1995 to December 2004 versus a 15 percent increase in the number of nonelderly adult SSI recipients. They also point out that growth in the SSDI rolls is likely to accelerate if policies are not changed. We will return to this topic later in the article.

The economic fortunes of people with disabilities are therefore not rising despite the rapidly growing expenditures for public programs intended to improve their economic well-being. Moreover, without raising taxes or reallocating funding from other federal programs, the current rate of expenditure growth cannot be sustained over time (SSA Trustees 2005), and the federal government's current and projected fiscal circumstances make any increase in funding extremely problematic. The Congressional Budget Office recently concluded that “even if taxation reached levels that were unprecedented in the United States, current spending policies could become financially unsustainable” (Congressional Budget Office 2005). In fact, the growth of SSDI expenditures is increasingly responsible for the overall fiscal crises facing the Social Security program, so some cuts in expenditures seem inevitable (Autor and Duggan 2006).

The Beginning of the Transition to Economic Self-Sufficiency Policy

Some thirty years ago, the emergence of the independent living movement planted the seeds of economic self-sufficiency policy. This movement first promoted the philosophy that people with disabilities should have the same civil rights, options, and control over choices in their own lives as people without disabilities have. Today, the idea of people with disabilities living, working, and participating in their communities has become the expectation and goal of many programs and policies, including the ADA passed in 1990, the Rehabilitation Act originally passed in 1973 and updated in 1998, the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and the 1999 Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act (Ticket Act), which provides employment and other supports that SSI and SSDI beneficiaries need in order to work.

Most recently, the Bush administration developed the New Freedom Initiative, a multifaceted effort to remove barriers to community living for people with disabilities and long-term illnesses. A number of new programs, demonstrations, and grant opportunities for states that have arisen from the Ticket Act and New Freedom Initiative offer opportunities to experiment with changes in disability programs and policies and to offer a wider range of supports to people with disabilities to help them become independent. For instance, the Assets for Independence Act of 1998 encourages low-income populations to contribute to Individual Development Accounts, but without jeopardizing their eligibility for cash benefits like SSI. When coupled with earned income, these savings programs can help address the current long-term poverty of many Americans with disabilities.

These changes have been accompanied by, and are synchronous with, a change in the disability paradigm (i.e., the concept of disability). The old paradigm, sometimes called the medical model, posits that disability is purely a biological phenomenon, a physical or mental impairment that makes the individual unable to participate in mainstream social activities, including work. The medical model now has been replaced by a social/environmental model (Nagi 1965; World Health Organization 2001), which recognizes the role of social and physical environments in the life experiences of people with disabilities. Each of the congressional initiatives mentioned earlier seeks, at least in part, to change a particular environment, such as making schools, workplaces, public places, and transportation more accessible.

Technological and other innovations have enabled people with serious physical and mental conditions to work productively, have changed the nature of work itself so that people with some physical and mental conditions can work, or have modified the work environment to accommodate workers with serious physical or mental conditions. These innovations have made it much easier for disability recipients to work today than two decades ago and have denigrated the medical model of disability among disability rights advocates. The types of disabilities among nonelderly adults are changing as well. Fewer workers experience acute illnesses such as heart attacks and strokes, and when they do, they are more likely to happen after retirement. Instead, more people with mental disorders, arthritis, back pain, and repetitive stress injuries are applying for SSI and DI.

No Change in Income Support Policy

Despite the emergence of the social/environmental model of disability, the two largest income support programs for working-age people with disabilities, SSDI and SSI, continue to reflect their historical roots and the discredited medical model. In 2002, these programs, along with the public health insurance benefits programs to which most participants are automatically entitled, accounted for about 75 percent of federal and state expenditures on working-age people with disabilities (Goodman and Stapleton 2005).

This year, 2006, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the SSDI program. In 1956, the Social Security retirement program was expanded to provide replacement income to workers over age fifty who could no longer work because of disability. Benefit amounts are essentially based on the same formulas applied to retirees; that is, they depend on the individual's past contributions to the program's financing, through payroll taxes. In other words, the program extended retirement benefits to those who needed to retire early because of a medical condition. In 1960, SSDI was expanded to cover workers of any age who had made sufficient payroll tax contributions and could no longer engage in a “substantial gainful activity,” or SGA, that is, could no longer work enough to earn more than a minimal amount (in 2006, $860 per month for nonblind beneficiaries and $1,450 for blind beneficiaries). The basic concept of the program, early retirement insurance for medical reasons, remained unchanged. In December 2004, the average disabled-worker beneficiary received $894 in benefits. Those entitled to spousal benefits received an average additional $233, and those with children received an average additional $257. But the amount of benefits varied widely. In the same month, 3.3 percent of disabled-worker beneficiaries received less than $300 for just themselves, and 2.6 percent received more than $1,700 (SSA 2005, tables 5.E1 and 5.E2), reflecting differences in past earnings and payroll tax payments.

SSI is a means-tested poverty program for elderly and disabled people, and its benefit levels are much lower. The federal program replaced the existing state programs in 1974. To determine disability, the federal program uses SSDI medical eligibility criteria. What distinguishes SSI from SSDI is that it is targeted to people with low incomes and limited resources. In 2005, unmarried SSI beneficiaries with no other income received a maximum of $564 in monthly benefits, or 72.6 percent of the federal poverty guideline for a one-person household; married couples with both individuals eligible and no other income received $846, or 81.3 percent of the federal poverty guideline for a two-person household. In December 2004, 8.5 percent of individual working-age recipients with disabilities received less than $50, and 55.4 percent received the individual maximum, $564 (SSA 2005, tables 2.B1 and 7.C1).

To become eligible for either program, an individual must demonstrate an “inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or to last for a continuous period of not less than twelve months” (italics added; SSA 1986). In other words, the program defines disability as an inability to work due to a medical condition, without reference to the environment.

Perhaps the most obvious evidence that the medical basis for the current system is badly flawed is the failure of the disability determination process, which was designed to implement the statutory definition of inability to work. The problems with the process have been well documented (General Accounting Office 1997, 2004; Social Security Advisory Board 2003). Despite the millions of dollars that a succession of SSA administrators have spent to fix the determination process, almost one-third of those who receive benefits receive them only after appealing an initial denial. Furthermore, the initial application process can take many months, especially in the case of a denial, and the appeals process can take much longer. Thus, many applicants who eventually prove to be eligible must go through a very long period—a year or more is not uncommon—when they do not know even whether they will receive benefits. Although many eligibility reversals on appeal may be the result of changes in medical conditions, SSA statistics show that many are allowed on evidence that was available to the initial examiner (Stapleton and Pugh 2001). The number of reversals of ineligibility for those who do appeal is relatively high (about 60 to 65 percent). There is convincing evidence also that the medical eligibility criteria are applied inconsistently across states (Gallichio and Bye 1980) and even across adjudicators within the same office (Stapleton and Pugh 2001; Social Security Advisory Board 2003).

On August 1, 2006, SSA substantially changed its disability determination process, with the hope of improving the consistency of decisions and shortening the processing time. But the new process does not address the main issue of the law itself, for the inability to work cannot be determined medically. Many working people have conditions that meet SSA's medical eligibility criteria, such as those who use a wheelchair, have a profound vision or hearing impairment, or have another disability. Nonetheless, the determination process presumes that such individuals are not able to work or can work only minimally based on one condition: that they are currently not working. Thus, the first step in the “medical” determination process is a work test: has the applicant earned less than the SGA amount for at least five months?

The disability determination process implicitly acknowledges that medical criteria alone do not determine whether somebody can earn more than the SGA, because the very first step screens out applicants who earn more than the SGA, regardless of their medical condition. If Congress were to allow the SSA to drop this work test and provide benefits to all who meet the medical criteria, millions of workers would likely qualify, thereby greatly accelerating the already significant growth in the disability programs' costs. But if Congress were to limit eligibility to only those with medical conditions resulting in no capacity to work above the SGA, millions would lose their benefits and many would suffer. No application would be allowed, for instance, solely on the basis of a significant vision impairment, a profound hearing impairment, or paralysis in both legs.

The reality is that medical advances, technical progress, and social change have created a world in which many people with disabilities are placed in an ever-broadening gray area between “able to work” and “not able to work.” Nonmedical characteristics of the individual and environment have become increasingly important to determining a person's ability to work. A growing portion of people with disabilities can work at some level but still need some type of assistance so they can attain or maintain a reasonable standard of living. Yet the Social Security Act contains the notion of a narrow, medically determinable line between those who can work above the SGA and those who cannot.

The Poverty Trap of Today's Support Policies

Today's income support programs and other policies that assume that people with certain physical or mental conditions cannot work create a poverty trap for many people with disabilities, because of both their paternalistic nature and their inability to keep up with societal changes. Instead of helping and encouraging people with disabilities to use their own abilities to stay out of, or escape from, poverty, they are built on the presumption that people with disabilities cannot work, and so they must provide most with low levels of benefits. Today's policies do too little to help people with disabilities lift themselves out of poverty by using their own abilities or to help them avoid falling into poverty in the first place. These programs also reinforce society's unrealistically low expectations about the ability of people with disabilities to participate successfully in the labor market.

The poverty trap has four components. The first is the determination of eligibility for Social Security disability programs discussed earlier. When people apply for disability insurance benefits, they must demonstrate to the SSA that they cannot work, must have worked long enough to qualify for benefits, must not be currently working, and must meet the SSA's medical eligibility criteria. Although many applicants for both SSDI and SSI may truly be unable to work, a significant number may actually be able to work, except for episodic symptoms of long-term conditions, inadequate health care, lack of reasonable accommodation, or limited skills that may greatly limit their employment opportunities. If these people's symptoms abate, if they receive rehabilitation or other training, or if an employer makes an accommodation, these applicants may be able to work at some future time. By instituting the nine-month trial work period in 1960 (which enables SSDI beneficiaries to work for nine months without losing their benefits) and other work incentives throughout the 1980s, policymakers recognized this possibility. But the extensive waiting period for eligibility (the determination process can take many months, plus SSDI's five-month waiting period) means that instead of trying to reenter employment during this period, applicants are encouraged to remain idle. Many may be learning for the first time that people with disabilities are not expected to work. They also will learn that when they do return to work, they will lose all or some of their benefits and risk losing their public health insurance.

Loss of benefits is the second important component of the poverty trap. The current rules sharply reduce benefits as a beneficiary's earnings increase. SSDI beneficiaries can earn up to the SGA without a loss of benefits, but after subtracting certain work-related expenses, if their earnings exceed the SGA amount by as little as one dollar and they have “used up” their trial work period, they will face the “earnings cliff ”; that is, they will lose all SSDI cash benefits if their earnings increase by any amount. Because many beneficiaries' benefits are above the SGA, their loss of income can actually be greater than their earnings. For example, those with SSDI benefits of $900 (not uncommon for beneficiaries with children or those with moderate before-disability earnings) will lose their entire benefit check if they earn $861 per month, the equivalent of $6.50 per hour for thirty hours per week. In addition, those SSDI beneficiaries on the rolls for less than twenty-four months will lose their opportunity to become eligible for Medicare, because of the twenty-four-month Medicare waiting period after the five-month SSDI waiting period ends. Once SSDI beneficiaries become eligible for Medicare, they can maintain their eligibility for eight years and can purchase Medicare coverage after that if they lose cash benefits because of their earnings.

SSI recipients face a different constraint: after their earnings reach $65 per month, their benefits are reduced by one dollar for every two dollars of additional earnings under SSI's Section 1619(a) program. Put differently, SSI recipients' income is implicitly taxed at a rate of 50 percent, a higher tax rate on earnings than that paid by even the wealthiest individuals. Indeed, the tax rate is even higher when considering payroll taxes, federal and state income taxes, or the possible loss of housing subsidies, food stamps, or other benefits. Moreover, because benefits cannot be adjusted during the month in which the income is earned, the beneficiaries often must reimburse the SSA for past benefit overpayments. SSI recipients who are eligible for Medicaid do not, however, risk losing their benefits as long as they continue to meet the SSI's medical eligibility requirements. They will continue to receive benefits even if they earn enough to reduce their SSI payments to zero, provided that their total income does not exceed a cap, which varies by state.

These rules penalize beneficiaries who try to augment their incomes through earnings, by means of benefit reductions that amount to high taxes on those earnings. For beneficiaries who are capable of returning to work and earn a monthly income much greater than their benefit payments (i.e., several thousand dollars per month), these penalties may be fairly inconsequential; that is, such beneficiaries can substantially increase their incomes through work, despite the penalties. Beneficiaries who are not capable of doing so, however, are trapped. They can raise their income through earnings to some extent, but the program rules create disincentives for them to do so beyond a minimal amount, and their limited job opportunities mean that if they leave the rolls entirely, they still will have little income.

Some experts have argued that the work disincentives associated with the income support programs are small. They point out that the maximum SSI benefit is below the poverty level and that the SSDI wage replacement rate (benefits divided by a measure of past earnings) also is low (Reno, Mashaw, and Gradison 1997). Both assumptions are correct and imply that the programs are not exceptionally generous; nonetheless, the work disincentives are stronger than these facts seem to imply, for several reasons.

SSA's actuaries estimate that the replacement rate ranges from 25 percent for those who earned $87,000 per year before entering the program (“high-earnings” beneficiaries) to 56 percent for those who earned $15,600 (“low-earnings” beneficiaries) (Office of the Actuary, SSA 2004). These relatively low replacement rates understate the size of the work disincentives. First, beneficiaries who return to work may lose some or all other benefits tied to disability. Second, because benefits receive more favorable tax treatment than earnings do, a dollar of earnings is worth less than a dollar of benefits. Third, due to their disability, the beneficiaries' potential earnings are likely to be lower than past earnings, so the replacement rate for potential earnings may be much higher than the replacement rate for past earnings. Fourth, the conventionally computed replacement rate does not consider that beneficiaries can earn up to the SGA and retain their earnings. For these beneficiaries, it is their potential earnings up to the SGA that should be in the denominator of the replacement rate. Consider a person who earns the SGA of $860 per month and receives benefits of $800. If her maximum potential earnings are less than $800 above the SGA, she cannot increase her income by increasing work. For this beneficiary, the relevant replacement rate—the reduction in benefits divided by the potential increase in earnings—is 100 percent or greater.

Some policymakers might be tempted to address the incentive issue by simply lowering either the benefits or the SGA. That would likely increase employment and earnings and reduce benefit payments, but it would also harm the many beneficiaries who are unable to work or who would find work to be a significant hardship. The benefits are not very generous, as noted earlier, and many beneficiaries live in or close to poverty. Presumably they would not be participating in the program if they had better alternatives. Policymakers interested in improving the well-being of people with disabilities, or at least not diminishing it, must realize that benefit cuts alone do just the opposite.

The third major component of the poverty trap is the complexity and poor coordination of support systems for people with disabilities, which extends beyond the fact that eligibility for many in-kind programs is contingent on earnings. The many in-kind supports available to people with disabilities—medical benefits, personal assistance, assistance with technology purchases, food, housing, transportation, education, and others—are administered by a variety of state and federal agencies and private organizations, each with its own rules, many of which are very complex. Substantial numbers of people with disabilities also receive cash benefits from programs other than SSDI and SSI, especially workers' compensation, private disability insurance, veterans' pensions or compensation, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Although these programs alleviate poverty for many, they also interact with SSDI and SSI in ways that are hard to understand and, in some cases, exacerbate work disincentives. Understanding, obtaining, and managing the various supports requires substantial effort. People with disabilities often must spend additional time doing everyday tasks, such as dressing, using public transportation rather than driving, or managing information. That effort reduces time and energy available for productive activities. As Oi (1978, 1992) noted, “Disability steals time.” The inefficiency of our current support system steals even more.

The support system's complexity also makes it very prone to errors. Some errors are committed by recipients because they do not understand the supports, how they interact, and their own responsibilities or because they just do not have the resources needed to comply with the program's rules. Other errors are committed by administrators, whose budgets and technical resources are often inadequate for completing complex tasks. One result is errors that can temporarily disrupt productive activities entirely. Complexity and errors also can lead to profound distrust of the system. As a result, those who receive supports often are reluctant to try something new, believing that they cannot rely on the system to support them, even if it would.

The final key component of the poverty trap is related to the other components: the self-fulfilling expectation, ingrained in the support system, that people with disabilities cannot support themselves or, perhaps worse, do not want to support themselves. When program administrators, staff, and members of the general public see that people with disabilities rely on public programs rather than work as their primary support, they conclude that such people cannot work or do not want to work. Some even advise against their working, because of the consequences for their supports. Thus, the programs foster low expectations for self-sufficiency and dependence becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. This culture is particularly harmful to individuals just beginning to adjust to a disability or a setback in health. Although people's own expectations may naturally decrease with an adjustment to disability, policies and programs should help them sustain high expectations rather than reinforce broad societal messages that lower them.

In this policy environment, many people with significant functional limitations and a relatively low earnings capacity face the following choice: They can work, receive wages, perhaps obtain some in-kind supports, and live in or near poverty. Or they can severely limit their work, navigate the support system, and receive income and in-kind benefits that also leave them in or near poverty. They are trapped. But a successful economic self-sufficiency policy would enable them to escape.

The Inadequacy of Current Initiatives and Reforms

Despite the intent of the many current policy reforms and initiatives, it seems unlikely that they will substantially improve the economic self-sufficiency of people with disabilities and offer them a higher standard of living, for three reasons. First, they do not adequately address work disincentives; second, they increase the already excessive complexity of the current support system; and third, they fail to address the unrealistically low expectations of the work capacity of individuals with disabilities when appropriate supports are provided.

The Ticket to Work Program (TTW) illustrates these three points. TTW was designed to help beneficiaries find gainful employment with sufficient earnings to enable them to leave the benefit rolls. SSA beneficiaries receive tickets they can assign to participating providers called Employment Networks (ENs) for training and employment assistance. SSA pays the ENs according to one of two schedules over a period of five years or longer. If the EN is to obtain the maximum payments under both schedules, the beneficiary must return to work and leave the rolls for at least sixty months. In effect, the EN receives a portion of program savings for helping beneficiaries go off benefits. State Vocational Rehabilitation Agencies can serve as ENs or can serve beneficiaries under a third, previously existing SSA payment system that has a performance incentive but does not require leaving the beneficiary rolls. The complex payment structure; the need for up-front capital to purchase training, equipment, and other services to make beneficiaries employable; and extensive paperwork requirements have discouraged many organizations from participating as ENs. A second problem is that TTW fails to address most of the SSI's and SSDI's work disincentives. Beneficiaries who redeem their tickets, receive training, and find employment still face the same SSDI earnings cliff and sharp reductions in SSI benefits as they did before the TTW. EN staff interviewed as part of SSA's evaluation effort explained that once some beneficiaries discover that TTW's goal is to increase beneficiaries' earnings enough to make them ineligible for benefits, they lose interest quickly (Thornton et al. 2004). Finally, the TTW program has not addressed societal expectations. To date, it has included only very limited marketing to employers, beneficiaries, or the general public about the program participants' work capacity.

The Medicaid buy-in program also illustrates these points. This program enables states to offer health insurance to working people with disabilities under a sliding premium scale, without losing benefits. As of the end of 2005, thirty-two states had active programs.1 Indeed, many states' implementation of the Medicaid buy-in falls short of the program's goal—if they have implemented it at all. In all but a few states, income and asset eligibility limits for buy-in programs are rather restrictive, especially for SSDI beneficiaries receiving relatively high SSDI benefits. In addition, the program rules regarding income, assets, and proof of work effort can be very difficult for people with disabilities and eligibility workers to understand. In many instances, because of automated eligibility systems that enroll individuals in various categories of Medicaid eligibility based on information submitted at application, a person may not even be aware that he or she is enrolled in a special Medicaid category that permits higher levels of earnings without loss of eligibility. Another problem noted by many representatives of state Medicaid buy-in programs is that the programs are able to address only one aspect of the work disincentives facing people with disabilities: loss of public health insurance owing to increased earnings. Moreover, the effectiveness of buy-in programs in promoting employment and self-sufficiency is severely hampered by the work disincentives associated with the SSDI cash cliff. Finally, marketing efforts so far have been very limited (Goodman and Livermore 2004).

Thus far, policymakers have taken a piecemeal approach to policy changes promising to promote economic self-sufficiency and increase the standard of living for people with disabilities. Reformers seem to be trying to at least partially correct specific problems with specific programs, but without addressing the many other problems that need to be corrected. In doing so, the reforms only make the programs more complicated and make them even harder to administer, but they fail to address their long-term fiscal health.

Disability Policy Goals

For people both with and without disabilities, support programs strive to achieve several goals, including

Adequacy: assistance levels should be adequate and keep people out of poverty.

Equity: assistance programs should provide comparable levels of assistance for people in similar situations.

Efficacy: assistance programs should identify individuals who need support and reject those who do not.

Positive incentives: recipients should be encouraged to help themselves, or at least not be discouraged from doing so.

Simplicity: the program should be easy for the target population to understand and easy for the government to administer.

Efficiency: the program should achieve its goals using as few resources as possible.

Fiscal and political sustainability: the program must have the ongoing support of taxpayers in order to remain stable and survive.

These goals have trade-offs; that is, emphasizing one goal often affects the achievement of another. For example, the goal of creating positive incentives seems directly at odds with the goal of providing adequate support to people just because they have little income; the availability of support from the program reduces the incentive for people to help themselves; and adequate support to keep eligible beneficiaries out of poverty could result in a program that is fiscally and politically unsustainable.

When the SSDI program was established, its purpose was to provide income replacement for individuals who could no longer work because of disability. Adequacy, efficiency, efficacy, and equity were emphasized over positive incentives because of the prevailing attitudes toward disability at the time and the belief that this was the most efficient approach. One could argue that during the program's early years, these goals were met. But as time passed, policymakers expanded the target population to help others who clearly needed assistance: younger people and people with medical conditions more difficult to diagnose. These expansions had the effect of blurring the line between those who could and could not work. Advances in technology and medical care further blurred the line. The model of income replacement after retirement became less and less appropriate, and as a result, the program's work disincentives became more and more problematic. Both participation in the program and its expenditures swelled; the program became less efficient and now appears to be unsustainable, especially in the face of current federal budget projections.

We therefore need to shift our thinking and reorient disability programs to new and innovative ways of changing these goals to reflect today's realities. Instead of piecemeal changes to programs that are already too complex, we need systemwide reforms that fundamentally change support policies by replacing today's outdated policies with economic self-sufficiency policies. This reorientation may not be smooth or easy, and hammering out the details of such major policy change will be difficult. Such wholesale reforms require principles to guide them. We recognize that these program elements cannot be specific at this stage, but we hope that discussing these principles will bring U.S. disability policy closer to a system encouraging economic self-sufficiency. A holistic approach to policy reform, rather than the adoption of one or two of these principles, is more likely to bring real and lasting change that will empower millions of people with disabilities to escape poverty. It is noteworthy that some European countries are actively considering many of these principles in their own efforts to reform disability policies (Marin, Prinz, & Queisser 2004; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2003).

Broadly speaking, the overall goal of the new system—and the one most difficult to achieve—should be maximum economic self-sufficiency at a reasonable standard of living for every person facing a significant challenge to employment because of functional limitations. This goal implies providing a reasonable standard of living (adequacy) along with work incentives that promote employment.

We advocate eliminating the inability-to-work requirement in favor of systemwide eligibility criteria designed to identify people with significant functional limitations, defined in the International Classification of Function as “a significant deviation or loss in body physiology or structure, such as loss of sensation in extremities, visual or hearing loss, paralysis, or anxiety” (World Health Organization 2001). Although some medical criteria will be needed to determine who is eligible for any support from the system, the eligibility criteria should move toward a functional definition of disability as recommended by others (e.g., Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2003); they should not include a work test or be designed to determine an inability to work. Put another way, we recommend uniform criteria for eligibility across all programs that do not use an inability-to-work standard.

This does not mean, however, that all people meeting the eligibility criteria should automatically receive cash assistance and other support, regardless of their earnings or other factors. Instead, the eligibility decision should be separate from decisions about the specific assistance to be provided. We recognize that those people who currently work and receive no program support would be tempted to apply for eligibility. In other words, the new eligibility criteria would likely encompass many who are not currently receiving benefits. So if eligibility automatically triggered substantial cash and health benefits, as it does under the current system, the program's costs would likely rise substantially. Instead, we propose more equitable strategies that would more efficiently offer support to all those meeting the new eligibility criteria—support designed to help many help themselves and reduce their reliance on public support. The advantage of this approach is that those who risk losing income owing to their disability will be identified early, and intervention can start early, when that risk becomes a reality, rather than after a long disability determination process during which applicants are not employed and may not have the medical or other services they need.

One way to reduce the demand for cash support would be to establish a rebuttable presumption of ability to work. The presumption would be that with appropriate supports, all eligible individuals could work and at least partially support themselves, despite the challenges posed by their functional limitation. This presumption could be automatically rebutted for those with the most severe impairments, but others would be expected to make good-faith efforts to work over an extended period, after which some might be classified as unable to work.

We emphasize that this presumption should not invalidate the other principles listed, as that would cause great harm to many people with disabilities. Deciding on equitable criteria to rebut the presumption of ability to work that are not subject to litigation will be difficult. Examples of disabilities that would rebut the presumption of ability to work would likely include those with sufficiently extreme functional limitations; those with a very short life expectancy due to illness or injury; those whose functional limitations are increasing owing to a chronic medical condition; and those who, despite appropriate supports (e.g., assistive technology, rehabilitation, supported employment), cannot find employment despite good-faith efforts. Those who successfully rebutted the presumption of ability would receive cash benefits and would be allowed to work, if they chose to, without penalty. Many of the medical eligibility criteria used for SSDI and SSI may be sufficient to rebut the presumption of ability to work, but many others would not be.

In accordance with the current system, the level of any cash benefits could depend on how much the beneficiary has contributed to the Social Security Trust Funds; that is, one of the rewards of working is better disability benefits. The benefits for those who have not contributed enough to the Trust Fund would be means-tested, as they are under today's SSI program, although the means test would have to be revised to allow recipients to earn their way out of poverty.

Incentives that make work pay would be a key component of the new system, with the goal of providing work incentives receiving a higher priority than under the current system. Those able to obtain only low-wage jobs or to work only a few hours would receive wage subsidies or tax credits offering them an incentive to work and improve their standard of living.

Those persons who could not attain a reasonable standard of living without it would receive financial support. Those who rebut the presumption of ability to work and those who cannot earn enough on a sustained basis would be eligible for sufficient income and in-kind benefits to give them a reasonable standard of living, considering any disability-related expenses they incur. The intent of this support would be to raise their income to the standard established as reasonable.

Those able to earn only a small amount would also be given incentives to improve their financial literacy, save money, acquire assets, and make investments. The current SSI program prevents recipients from escaping poverty because of stringent restrictions on their acquisition of wealth. We envision a program that instead would help such persons escape poverty through positive incentives to acquire wealth, up to a certain limit. One example is individual development accounts in which some of beneficiaries' savings would be matched by outside sources, including employers (as many now do for retirement benefits), family members, and charitable organizations. Such incentives need not be costly, because once the recipients acquire enough money, they would become more self-sufficient.

The early and timely provision of supports likely to help first-time workers entering the workforce and help workers adjusting to the onset of a disability or its exacerbation stay employed should become a cornerstone of rehabilitation efforts. People should not have to wait for an application for income support benefits to be processed before receiving rehabilitation. But this speedup will require much better coordination between rehabilitation support and public and private benefits than under the current system, making it possible to identify much earlier those at risk for losing their job. Moreover, those unable to rebut the presumption of ability to work will have a strong incentive to make good use of rehabilitation services.

Beneficiaries and, as needed, their agents/representatives should be given substantial control over the delivery of supports. For instance, rehabilitation programs could adopt the empowerment model used by centers for independent living, under which beneficiaries have more control over the delivery of supports. When feasible, they would be allowed to choose the providers, and some options would allow them to obtain services without interrupting their work activities.

Both beneficiaries and providers should be responsible for achieving the program's goals. The beneficiaries would be given stronger incentives to contribute to their own support and, when possible, would be held responsible for doing so. For those who have not rebutted the presumption of ability to work, this would include work effort requirements. Program administrators and staff would be held to a similar standard. Accordingly, errors in administration or the failure to take timely action on behalf of a beneficiary could result in penalties payable to the beneficiary. For example, a beneficiary who begins working and accurately reports his or her earnings but still receives overpayments should not be penalized for them. Helping beneficiaries achieve economic self-sufficiency and a reasonable standard of living and the success of their effort would be the principal criteria for assessing the program's performance. The implementation and enforcement of such requirements also would help alleviate beneficiaries' distrust of the current programs' federal and state administrators.

Individuals should have access to health care and assistive technology that is not linked to employment. Access to health care should not be a disincentive to work and should not stand in the way of treatment needed to return to work. Eligible individuals, particularly those with chronic conditions or requiring personal assistance, should have access to assistive technology or other long-term services, regardless of their employment status. Persons with impairments who currently are working would be eligible for health insurance, assistive technology, and other supports to enable them to keep their job, regardless of their eligibility for cash benefits. Employers might be expected to contribute to the cost of their health care, as they do for other workers, and those with an income higher than that needed for a reasonable standard of living would be charged sliding-scale premiums, similar to those of the Medicaid buy-in program.

Other supports should be well coordinated, encourage work, easy to navigate, tailored to individual needs, and efficiently delivered. Beneficiaries would access support services through a single point of entry in the system rather than separately from multiple agencies and administrators. Supports like assistive technology and rehabilitation would not be contingent on work except to the extent that they are needed to support work. Providers would be paid through a system encouraging them to meet individuals' needs efficiently. Those with an income higher than that needed to support a reasonable standard of living would be expected to pay, on a sliding scale, for some of the services. Likewise, employers would be expected to contribute to the extent that such services might substitute for benefits they offered to other workers (e.g., under the Family and Medical Leave Act) or for expenses falling under the ADA's “reasonable accommodation” requirement for covered employers. Employer disability insurance and pension plans, along with workers' compensation insurance, would be integrated to support the objectives of the public program. To the extent practical, people with disabilities would receive support services (e.g., health care, education, training, job search, and transportation) from the same providers that deliver similar services to others.

Finally, system reforms must be accompanied by public awareness campaigns designed to raise societal expectations about the work capacity of people with disabilities. Policy changes in line with the principles described earlier should gradually lead to more public awareness of the capabilities of people with disabilities and greater understanding of their value to society. But these changes will come slowly and may falter without a significant and sustained effort to address misconceptions and raise society's awareness of the work capacity of people with disabilities. The message of the campaign might be that workers with disabilities are a significant economic resource, to encourage leaders to recognize that tapping into that resource is an important opportunity, especially as the baby boom generation enters its retirement years, which is perhaps the greatest challenge facing the U.S. economy today.

The Many Challenges to Further Reforms

The greatest challenge to reform is cost. The readers of this article may imagine that a program following the principles just described is not affordable. Currently, the primary objective of program reforms usually is a reduction in spending, and much of the interest in the disability policy reform is based on concerns about the fiscal health of the largest programs serving people with disabilities. Hence, if they are to attract political support, any reforms will need to promise less growth of expenditures and/or more growth of revenues, through income and payroll taxes. A well-designed system could offset the political pressure to reduce expenditure growth with features that voters generally support, such as greater personal responsibility for one's own actions and well-being, more efficient use of public resources, and a more equitable distribution of benefits.

We are convinced that a well-designed program could reduce expenditure growth by making better use of existing resources. The most important of these resources is the ability of people with disabilities to help themselves, which under our current system is often discounted. Added to this are the resources currently wasted by a complex, poorly integrated, inefficient system of supports that could be used effectively in a reformed system.

Even if we are right, reform faces many other hurdles. How can we extract the resources from the many largely independent public programs that now serve people with disabilities, all with their own self-interested stakeholders? How can a government bureaucracy effectively administer benefits that are tailored to the support needs of an extremely heterogeneous population? Most important, how can we avoid irreparably harming millions of those we intend to help as we move to a new system and experiment with a new approach?

Many more problematic design issues must be addressed, and another article would be required to address them all. For example, the eligibility determination process would need to be mapped out. Even though the new process would have a less contentious purpose than the current process does, it could demand more information to determine support needs. Furthermore, we need a process to rebut the presumption of ability to work. If those who are successful are allowed to work without penalty, consistent with the policy goal, they might have a strong incentive to rebut the presumption of ability to work—incentives that would be as problematic for this process as they are now. Whether or not such incentives are problematic depends on both the generosity of benefits for those who work and the extent to which policy changes raise individual and social expectations about the ability of people with disabilities to work. This example illustrates a fundamental design issue: a change in one design feature (e.g., work incentives) has implications for many other design features (e.g., eligibility determination). There are many trade-offs to consider, and the development of a program that will meet our policy goals will require extensive investments in the design and testing of various program features.

Reasons for Optimism

Given these challenges, there are many reasons for pessimism about the design and implementation of reforms that will move toward the objective of greater economic self-sufficiency and better living standards. There are, however, important reasons for optimism.

Historically, the response of people with disabilities to fewer incentives to work provides considerable reason for optimism. Ample anecdotal evidence as well as some empirical evidence shows that many disability program beneficiaries restrain their earnings only to preserve their eligibility for public income support and health benefits (O'Day and Killeen 2002; Stapleton and Tucker 2000). Research also shows that many people who enter disability programs do so only after losing their job, for reasons outside their disability, such as layoffs due to a recession or industrial restructuring (Stapleton, Wittenburg, and Maag 2004). Between 1984 and 2003, Duggan and Imberman (2006) attributed 24 percent of the SSDI's growth for men and 12 percent of its growth for women to two significant recessions. They traced another 28 percent of the growth for men and 24 percent for women to rises in earnings inequality that, because of the way that SSA indexes past earnings, increased the earnings replacement rate for those with few skills. Their analysis attributed another 53 percent of the growth for men and 38 percent for women to regulatory changes in eligibility requirements, especially related to psychiatric conditions and to pain related to musculoskeletal disorders. Autor and Duggan (2003) earlier showed that these same factors reduced the employment of people with disabilities during this period.

We do not intend to suggest that those entering the SSDI rolls because of the economic changes just described are somehow unworthy of support or that the changes in eligibility rules were unwarranted. In fact, we suspect that most reasonable taxpayers would conclude that most of those entering the programs because of these changes are worthy of support. Instead, we are pointing to the historical evidence that people with disabilities work less, and rely more on public support, when their incentive to work is undermined by our current programs or changes in the economy. Many work up to the level at which they can retain their benefits. It seems reasonable to expect, therefore, that many people will try harder to support themselves in response to policy reforms that encourage them to work.

Furthermore, a well-designed policy could have wide-ranging effects. One line of research based on the historical record estimates that around 30 to 40 percent of SSDI applicants would work if it were not for the disincentives associated with the SSDI program (Bound 1989, 1991; Bound, Burkhauser, and Nichols 2001; Chen and van der Klauuw 2005; Parsons 1991). Duggan and Imberman's findings (2006) also suggest that a well-designed program would have a large impact, as they attributed 82 percent of the SSDI growth for men and 72 percent for women between 1984 and 2003 to factors that discouraged working.

The experience of the Department of Veterans Affairs Disability Compensation program (VADC) for veterans who become disabled on active duty also offers some encouragement. Eligible veterans receive benefits, regardless of their earnings. Like SSDI and SSI, eligibility is based on medical evidence and is intended to reflect a person's ability to work. But there is no work test. In addition, the outcome of the determination may be a specified “partial disability,” in which the veteran receives a percentage of the full benefit.

An examination of data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation reveals that earnings are substantially greater and poverty is significantly lower among beneficiaries of this program than among their counterparts on SSI or SSDI. For example, poverty rates among nonelderly adult recipients of VADC benefits were 8 percent in 2001 versus 40 percent and 22 percent for SSI and SSDI recipients, respectively (Duggan, Rosenheck, and Singleton 2006). This improvement was largely because their earnings were much higher ($2,300 per month) than the earnings of those on SSI and/or SSDI (just $80 per month on average). Although this difference may reflect differences in disability type, health, or other beneficiary characteristics, it does suggest that removing work disincentives for disability recipients would increase their work effort and lower the likelihood of their being in poverty.

Autor and Duggan (2006) suggest considering reforms of SSDI that would follow the VADC model (i.e., no restrictions on earnings and partial benefits to control costs). Others, however, believe that this approach would be problematic because more workers would become eligible for benefits and because applicants and advocates would press for a greater percentage of disability associated with their specific conditions or combinations of conditions.

Whether or not VADC is a viable model for SSDI reforms, the program's experience is encouraging in that it demonstrates the ability of people with severe disabilities to contribute substantially to their own support and help keep themselves out of poverty.

The private disability insurance (PDI) industry, which helps employees with private disability insurance coverage to return to work, may also be an instructive model. PDI companies have a vested interest in their beneficiaries' returning to work, as they must pay cash benefits to those who do not. PDI companies use many of our recommendations. They target beneficiaries who, they believe, can return to work and use their close relationships with employers to keep their job or, for those who cannot return to their previous position, find a new job. Although rigorous evidence on the effectiveness of such efforts is rare (O'Leary and Dean 1998), recent research demonstrates their promise (Allaire, Li, and LaValley 2003; Mitra, Corden, and Thornton 2005). Private disability insurers also use lump-sum payouts and benefit offsets, to reduce both their liability and their work disincentives.

One difficult feature of the current policy is that PDI benefits interact with SSDI benefits to discourage private insurers' efforts to return clients to work because PDI benefits are reduced by one dollar for every dollar of SSDI benefits received. At some point, it becomes more cost-effective for the private insurer to help their clients obtain SSDI coverage rather than continuing to try to return them to work. A disability policy that is oriented toward greater self-sufficiency would, instead, encourage such efforts. One approach would establish a private-public benefit under which the government would compensate PDI companies for administering a combined benefit.

Changes in U.S. family policy through passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, the 1993 expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income families, and related state policy changes in the 1990s also provide reason for optimism. Researchers have found that if incentives to work are strengthened and work expectations and supports are built into public policy, the employment, earnings, and economic self-sufficiency of a historically dependent population—mostly unmarried mothers—can be significantly increased over a very short period. Even progressive critics of the reforms have been astonished by the size of the impacts (Winship and Jencks 2004). Interestingly, the reforms did little to slow the growth of government expenditures on families, as the growth of tax credits outpaced the declines in welfare benefits, yet they remain popular with the electorate because of their orientation to work and personal responsibility (Besharov 2003).

This does not mean that family policy reforms offer a blueprint for disability policy reforms (Burkhauser and Stapleton 2004b; Stapleton and Burkhauser 2003). In fact, the experiences of low-income families under family policy reform provide much reason for caution. Moreover, the combination of changes to incentives, work expectations, and supports hurt some families even while helping others. In many cases, earnings gains may not have been enough to compensate for both benefit reductions and the increase in parental work effort. Many parents with disabilities were exempted from work requirements, and the states found it cost-effective, from their own perspective, to push them onto SSI, rather than give them the supports they might need to work. Those not exempted or not eligible for SSI continue to struggle with the new work requirements and inadequate work supports. If disability reforms followed in the footsteps of welfare reforms without analyzing the effects of these reforms on people with disabilities or the differences between welfare and disability programs, many people with disabilities would be hurt.

Perhaps the most compelling reason for optimism is that progress in medical and assistive technologies continues to improve the ability of people with significant functional limitations to be productive. Over time, when accompanied by the economic self-sufficiency approach we described, medical and technological innovations will encourage the labor market participation of would-be workers with many types of disabilities. By the same token, paternalistic programs will become more and more inefficient and inequitable, and those who must rely on them will be less and less able to enjoy the benefits of our nation's prosperity.

The issue is not whether we will move to an economic self-sufficiency policy but rather how and how fast we will move and how much progress we will achieve toward the goals of greater economic self-sufficiency and a higher standard of living for people with disabilities. Addressing this challenge will require a full and open debate.

Acknowledgments

Research for this paper was conducted at the Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Economic Research on Employment Policy for Persons with Disabilities at Cornell University, funded by the U.S. Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (Cooperative Agreement no. H133B980038). The contents of this paper do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government (Edgar, 75.620 (b)). Nor is it endorsed by the Cornell University or the American Association of People with Disabilities.

Endnote

Reported on the website of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/TWWIA/07_BuyIn.asp (accessed December 30, 2005).

References

- Allaire SH, Li W, LaValley MP. Reduction of Job Loss in Persons with Rheumatic Diseases Receiving Vocational Rehabilitation. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;48(11):3212–18. doi: 10.1002/art.11256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autor D, Duggan M. The Rise in the Disability Rolls and the Decline in Unemployment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118(1):157–205. [Google Scholar]

- Autor D, Duggan M. The Growth in the Social Security Disability Rolls: A Fiscal Crisis Unfolding. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(3):71–96. doi: 10.1257/jep.20.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharov DJ. The Past and Future of Welfare Reform. The Public Interest. 2003;(Winter):4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bound J. The Health and Earnings of Rejected Disability Insurance Applicants. American Economic Review. 1989;79:482–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bound J. The Health and Earnings of Rejected Disability Insurance Applicants: Reply. American Economic Review. 1991;81(5):1427–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bound J, Burkhauser RV, Nichols A. Tracking the Household Income of SSDI and SSI Applicants. University of Michigan Retirement Research Center Working Paper no. 2001–009.

- Burkhauser RV, Daly MC, Houtenville A. How Working-Age People with Disabilities Fared over the 1990s Business Cycle. In: Budetti P, Burkhauser RV, Gregory J, Hunt A, editors. Ensuring Health and Income Security for an Aging Workforce. Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research; 2001. pp. 291–346. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Houtenville AJ, Rovba L. Rising Poverty in the Midst of Plenty: The Case of Working-Age People with Disabilities in the 1980s and 1990s. Ithaca, N.Y.: Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Economic Research on Employment Policy for People with Disabilities, Cornell University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Houtenville AJ, Wittenburg DC. A User's Guide to Current Statistics on Employment of People with Disabilities. In: Stapleton DC, Burkhauser RV, editors. The Decline in Employment of People with Disabilities: A Policy Puzzle. Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research; 2003. pp. 23–86. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Stapleton DC, editors. The Decline in Employment of People with Disabilities: A Policy Puzzle. Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Stapleton DC. The Decline in the Employment Rate for People with Disabilities: Bad Data, Bad Health, or Bad Policy? Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2004a;20(3):185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Stapleton DC. Employing Those Not Expected to Work: The Stunning Changes in the Employment of Single Mothers with Children and People with Disabilities in the United States in the 1990s. In: Marin B, Prinz C, Queisser M, editors. Transforming Disability Welfare Policies: Toward Work and Equal Opportunity. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Publishing Co; 2004b. pp. 321–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, van der Klauuw W. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; The Work Disincentive Effects of the Disability Insurance Program in the 1990s. September, Working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. The Long-term Budget Outlook. 2005. [accessed August 22, 2006]. Executive Summary. Available at http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=6982&sequence=0. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M, Imberman S. Why Are Disability Rolls Skyrocketing? The Contribution of Population Characteristics, Economic Conditions and Program Generosity. In: Cutler David, Wise David., editors. Health at Older Ages. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press; 2006. Forthcoming in. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M, Rosenheck R, Singleton P. Federal Policy and the Rise in Disability Enrollment: Evidence for the VA's Disability Compensation Program. [accessed August 22, 2006]. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. W12323, Available at SSRN http://ssrn.com/abstract=912433. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gallichio S, Bye B. Consistency of Initial Disability Decisions among and within States. 1980. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Social Security Administration, Office of Research and Statistics, Staff Paper no. 39. SSA Publications no. 13-11869, July.

- General Accounting Office. Social Security Disability: SSA Must Hold Itself Accountable for Continued Improvement in Decision-Making. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1997. [accessed August 22, 2006]. GAO-97-102, Available at http://www.gao.gov/archive/1997/he97102.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- General Accounting Office. SSA Disability Decision Making: Additional Steps Needed to Ensure Accuracy and Fairness of Decisions at the Hearing Level. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2004. [accessed August 22, 2006]. GAO-04-14, Available at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d0414.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman N, Livermore G. The Effectiveness of Medicaid Buy-in Programs in Promoting the Employment of People with Disabilities. Washington, D.C.: Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Advisory Panel; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman N, Stapleton DC. Program Expenditures for Working-age People with Disabilities in a Time of Fiscal Restraint. Ithaca, N.Y.: Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Economic Research on Employment Policy for People with Disabilities, Cornell University; 2005. [accessed August 22, 2006]. Policy Brief, Available at http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/edicollect/189. [Google Scholar]

- Marin B, Prinz C, Queisser M. Transforming Disability Welfare Policies: Toward Work and Equal Opportunity. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S, Corden A, Thornton P. Recent Innovations in Great Britain's Disability Benefit System. In: Honeycutt T, Mitra S, editors. Learning from Others: Temporary and Partial Programs in Nine Countries. New Brunswick, N.J.: Final Report for the Disability Research Institute, Rutgers University; 2005. pp. 132–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nagi S. Some Conceptual Issues in Disability and Rehabilitation. In: Sussman MB, editor. Sociology and Rehabilitation. Washington, D.C.: American Sociological Association; 1965. pp. 100–113. [Google Scholar]

- O'Day BL, Killeen M. Does U.S. Federal Disability Policy Support Employment and Recovery for People with Psychiatric Disabilities? Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2002;20:559–83. doi: 10.1002/bsl.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Actuary, Social Security Administration. Washington, D.C.: The 2004 OASDI Trustees Report. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara A, Cooper E. Boston: Technical Assistance Collaborative; Priced out in 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oi W. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor; Three Paths from Disability to Poverty. Technical Analysis Paper no. 57, ASPER, October. [Google Scholar]

- Oi W. Work for Americans with Disabilities. In: Orlans H, O'Neill J, editors. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 1992. pp. 159–74. September. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary P, Dean D. International Research Project on Job Retention and Return to Work Strategies for Disabled Workers. International Labour Organization; 1998. Study Report USA. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Transforming Disability into Ability. Paris: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons DO. The Health and Earnings of Rejected Disability Insurance Applicants: Comment. American Economic Review. 1991;81(5):1419–26. [Google Scholar]

- Reno VP, Mashaw JL, Gradison B. Disability: Challenges for Social Insurance, Health Care Financing and the Labor Market. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration (SSA) A History of the Social Security Disability Programs. [accessed August 22, 2006]. Available at http://www.ssa.gov/history/1986dibhistory.html.

- Social Security Administration (SSA) Social Security Bulletin, Annual Statistical Supplement. 2005. [accessed August 22, 2006]. Available at http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2005. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration (SSA) Trustees. 2005 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds. 2005. [accessed August 22, 2006]. Available at http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/TR05/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Advisory Board. The Social Security Definition of Disability. Washington, D.C.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton DC, Burkhauser RV. Contrasting the Employment of Single Mothers and People with Disabilities. Employment Research. 2003;10(30):3–6. Newsletter of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton DC, Pugh MD. Evaluation of SSA's Disability Quality Assurance (QA) Processes and Development of QA Options That Will Support the Long-Term Management of the Disability Program. Report to SSA. [accessed August 22, 2006]. Available at http://www.lewin.com/Lewin Publications/Human_Services/Publication-13.htm.

- Stapleton DC, Tucker A. Will Expanding Health Care Coverage for People with Disabilities Increase Their Employment and Earnings? Evidence from an Analysis of the SSI Work Incentive Program. In: Salkever D, Sorkin A, editors. Research in Human Capital and Development. Vol. 13. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press; 2000. pp. 133–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton DC, Wittenburg D, Maag E. A Difficult Cycle? The Effect of Labor Market Changes on the Employment and Program Participation of People with Disabilities. Ithaca, N.Y.: Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Economic Research on Employment Policy for People with Disabilities, Cornell University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton C, Livermore G, Stapleton DC, Kregel J, Silva T, O'Day B. Evaluation of the Ticket to Work Program: Initial Evaluation Report. 2004. Report from Mathematica Policy Research and Cornell University to the Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers R. Ithaca, N.Y.: Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Disability and Demographic Statistics, Cornell University; A User Guide to Disability Statistics from the American Community Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Winship S, Jencks C. Welfare Reform Worked—Don't Fix It. Christian Science Monitor. 2004:9. July 21, p. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]