Abstract

Medicare could become an innovative leader in using financial incentives to reward health care providers for providing excellent and efficient care throughout a patient's illness. This article examines the variations in cost and quality in the provision of episodes of care and describes how a pay-for-performance payment system could be designed to narrow those variations and serve as a transition to a new Medicare payment policy that would align physicians' incentives with improvements in both quality and efficiency. In particular, Medicare could stimulate greater efficiency by developing new payment methods that are neither pure fee-for-service nor pure capitation, beginning with a pay-for-performance payment system that rewards quality and efficiency and moving to a blended fee-for-service and case-rate system.

Keywords: Medicare, efficiency, pay for performance, payment incentives, payment reform

The need to improve the U.S. health care system is becoming widely recognized. To this end, the recent compilation of measures, by the Commonwealth Fund's Commission on a High Performance Health System, over a range of health system performance domains (including quality, access, equity, and efficiency) produced an overall score for the system of 66 percent (Schoen et al. 2006). In addition, a survey by the Commonwealth Fund of the public's views of the health care system indicates that 76 percent believe that it needs to be fundamentally changed or rebuilt completely. Medicare, the largest single payer for health services in the United States, accounting for more than 17 percent of national health expenditures in 2005 (Catlin et al. 2007), is looked to as a source of innovation. According to a Commonwealth Fund survey of health care opinion leaders, 89 percent of the respondents agreed that Medicare should use its leverage to reward providers for quality and efficiency (Harris Interactive 2005).

Medicare's elderly and disabled beneficiaries are particularly dependent on the quality, effectiveness, and coordination of the care they receive. Moreover, Medicare's size (it will spend $425 billion on health services in 2007) and projected rapid growth (that figure will almost double to $842 billion by 2017) place tremendous pressure on its own solvency, as well as on both the federal budget and the economy as a whole (Congressional Budget Office 2007). Medicare therefore needs to be a leader in improving both the clinical care that it buys and its cost-effectiveness so as to be better able to meet the needs of its beneficiaries, to enable it to stay solvent, and to serve as an example for similar improvements throughout the health care sector.

To reach these goals, financial incentives should be introduced that reward health care providers for excellent and efficient care throughout a patient's illness. This article examines the problems with the way that Medicare now pays and the wide variation in its utilization and costs—with no apparent relation to outcomes; discusses Medicare's tests of new ways to reward higher quality and/or greater efficiency; and outlines a new payment policy for Medicare that would build on these initiatives to align physicians' incentives with the desired improvements in quality and efficiency and serve as a model for other payers, including Medicaid and private insurers. This payment strategy would begin by rewarding quality and efficiency and narrowing variations across the country. Then it would move to a blended fee-for-service and case-rate system that would encourage better, more coordinated, and more efficient care while still allowing sufficient flexibility to respond to patients' needs. Such a system could begin by reducing payments to providers with high episode costs and provide the database and experience needed to construct fair, but effective, payment reform.

Negative Incentives in Medicare Payments

Medicare's current payment system is based on a practice of paying the same rate for the same service, with prospective payment rates based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) for inpatient hospital stays and a fee schedule based on resource-based relative values for physicians' visits and procedures. Such a system of payment rewards those hospitals and physicians that efficiently produce those units of care (hospital stays and physicians' visits and procedures) because they can pocket any difference between the fixed price they are paid for each unit and the amount it costs them to produce it. The main disadvantage of this approach is that although it rewards providers for producing each unit of care efficiently, it also rewards providers for producing a greater quantity of services, even if the same or better patient outcomes could be achieved with fewer services or a less expensive combination of services. As a result, Medicare's payment policy still does not encourage efficiency in its overall provision of care over time or over an episode of illness. In fact, this policy may discourage both quality and efficiency by rewarding more care rather than more appropriate, better-coordinated care.

From this broader perspective, overall patient care would be delivered more efficiently by defining the unit of payment to cover the entire treatment episode or a set period of time for a patient or population with a given chronic health condition or problem (Grossman 1972; Hornbrook 1995; Porter and Teisberg 2004). This is quite different from the current Medicare fee-for-service approach, which focuses exclusively on the components of patient care.

Medicare's capitation of private Medicare Advantage (MA) plans is the ultimate population-based system of payment. Plans are paid a fixed rate for each enrollee, with a risk adjustment (based primarily on the individual's clinical history) to make sure that the payment that each plan receives reflects its enrollees' relative anticipated expense. This gives plans an incentive to minimize the overall cost of care. They may do so by emphasizing preventive care, better coordinating care across providers, and pursuing any of a number of strategies to make health care more efficient. They also may do so by reducing access to care that patients might—rightly or wrongly—decide that they need. The perception of this type of behavior, however, led to the “managed care backlash” of the late 1990s, from which medical insurance plans are still recovering (Marquis, Rogowski, and Escarce 2004). Although enrollment in Medicare's private plans has rebounded from 5.3 million in 2003 (1.6 million fewer than in 1999) to 8.3 million in 2007, MA still makes up only 19 percent of Medicare beneficiaries, leaving the other 81 percent in the fee-for-service program (Kaiser Family Foundation 2007).

Even within MA plans, the way that providers are paid often rewards overuse. A growing proportion of MA enrollment (11 percent in November 2006) is in private, fee-for-service plans, which pay their providers Medicare fee-for-service rates (Gold 2007). Moreover, most managed care plans—whether or not they are MA plans—are not integrated delivery systems but insurance products that typically pay providers, especially specialist physicians, on a fee-for-service basis. Most providers are unwilling to accept full capitation, which would put them financially at risk for the total care of their patients. Therefore, the incentives for most providers in managed care plans are similar to those in the fee-for-service system, although these incentives may be mitigated by providers' concern about being excluded from networks if their patients incur high total costs (Rowe 2006). Managed care plans also are beginning to use pay-for-performance incentives to reward higher-quality providers or the adoption of information technology, but very few base rewards on cost performance (Rosenthal et al. 2006).

In short, the Medicare program must be significantly changed in order to reward efficiency on an episode or population basis. Among the issues that need to be addressed are the classification of conditions, the length of the payment episode, and the way in which payment is to be structured and allocated among the multiple providers that may be providing care during the episode or over a period of time.

Building Blocks of a New Payment System

There is a substantial literature on the methods of classifying chronic conditions and adjusting expenditures for risk based on the clinical profiles of given population groups (Pope et al. 2004), and Medicare has adopted a method of adjusting risk for its managed care plans. Although these risk-adjustment methods do not explain much of the variation in outlays, they are deemed sufficiently adequate to be part of current Medicare policy.

The definition of a payment episode would depend on the condition for which the patient is being treated. For beneficiaries with chronic, ongoing conditions like diabetes, the episode might be all the care for a given population with that condition for a fixed time period, such as a year. For an acute condition like acute myocardial infarction, the episode may be the time from the beginning to the end of treatment for that condition.

The definition of episodes of illness has made substantial progress. Private insurers typically use “episode groupers” to calculate the total medical claims for patients with a given condition; for example, claims associated with diabetes are grouped together, and claims associated with heart disease are grouped together (Davis 2006). If a patient has multiple chronic conditions, the claims are divided among the different conditions. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has found that different commercial episode-group methodologies yield different results, raising concerns about the methodologies' consistency (MedPAC 2006). Moreover, the number of episodes per Medicare beneficiary vary geographically, with some high-cost areas having low costs per episode but larger numbers of episodes for otherwise apparently similar groups of patients (MedPAC 2006). Further work is required to refine the episode-group methods, but their use in private insurance pay-for-performance and performance-monitoring initiatives already has proved helpful.

Another major issue is that care during an episode of illness or during a specified period of time often is a shared responsibility of multiple providers: hospitals, primary care physicians, surgeons and other specialist physicians, and other independent providers such as physical therapists and inpatient rehabilitative services. When moving from measuring efficiency to rewarding providers for quality and efficiency, the thorniest question is how best to allocate the financial incentives for physicians, hospitals, and other providers to reward higher performance in the joint provision of a patient's care. This is most easily resolved when the “provider” is an integrated delivery system or large physician-group practice that provides the bulk of the beneficiary's care. Other options are creating new organizational entities such as physician-hospital organizations or networks of independent physician practices; basing such rewards on the performance of all providers in a particular geographic area or other definable connecting characteristics; and other data-based methods for assigning responsibility for efficiency across hospitals, physicians, and other providers, like rewards or financial penalties proportional to their total contribution to cost. We will consider these alternatives in greater detail later.

Improving Performance by Reducing Variation

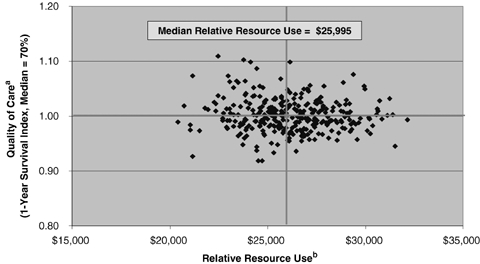

Despite the mediocre performance of the U.S. health care system demonstrated in almost any set of measures, that performance can be improved. The extent to which both quality and cost vary across geographic areas is troubling because it indicates how much worse performance is in some areas than others. But these variations also provide benchmarks for improvement because the data strongly indicate that areas with the highest quality and best outcomes generally are not those with the highest costs (Figure 1). That is, these data imply that quality improvement and greater efficiency do not need to be a trade-off if efforts to achieve both are appropriately targeted.

Figure 1.

Wide Variability in Quality and Costs of Care for Medicare Patients Hospitalized for Heart Attacks, Colon Cancer, and Hip Fracture.

aIndexed to risk-adjusted one-year survival rate (median = 0.70).

bRisk-adjusted spending on hospitals' and physicians' services using standardized national prices.

Data: From E. Fisher and D. Staiger, Dartmouth College analysis of data from a 20% national sample of Medicare beneficiaries.

Source: Commonwealth Fund National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance, 2006.

Examining geographic variations in Medicare beneficiary cost and quality is instructive, therefore, for at least four reasons. (1) As stated earlier, the extent of geographic variation indicates that money can be saved and quality improved if all providers achieve benchmark levels of performance. (2) The extent of variation suggests how long these providers will need to reach benchmark performance levels. (3) The geographic variations show that a particular area could serve as a model for pay-for-performance. Accordingly, understanding more about the level and distribution of performance both within and across different areas could help with the design of such a model. (4) Finally, this information might help identify exemplary performers' techniques for achieving high quality and low costs and help spread those best practices among the other providers.

An example of one benefit from reducing the variations in cost and quality across geographic areas is the analysis of 306 U.S. hospital referral regions, defined by the referral patterns of hospital service areas (Fisher et al. 2004; Skinner, Staiger, and Fisher 2006). When ranking these regions from most costly to least costly for the Medicare beneficiaries' three most expensive chronic conditions (diabetes, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), the ratio of annual costs for the tenth percentile of the distribution (the 10 percent of the regions with the highest costs) to the ninetieth percentile (the 10 percent of the regions with the lowest costs) ranged from 1.87 to 2.14—about a twofold variation for each condition across the regions (Table 1). Moreover, there was no systematic relationship across the regions between total Medicare costs and quality of care (Commonwealth Fund Commission 2006).

TABLE 1.

Costs of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries with Multiple Chronic Conditions, by Hospital Referral Region (HRR), 2001

| Total Costs per Beneficiary per Year | 10th Percentile HRR | Median HRR | 90th Percentile HRR | Ratio of 10th to 90th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes only | $7,165 | $5,579 | $3,823 | 1.87 |

| COPD only | $12,083 | $8,967 | $6,438 | 1.88 |

| CHF only | $17,828 | $13,101 | $8,746 | 2.04 |

| Diabetes + COPD | $18,024 | $12,307 | $8,872 | 2.03 |

| Diabetes + CHF | $27,310 | $16,695 | $12,747 | 2.14 |

| CHF + COPD | $32,732 | $20,143 | $15,355 | 2.13 |

| All three chronic conditions | $43,973 | $28,604 | $20,960 | 2.10 |

Notes: Hospital referral regions refer to those with fifty or more Medicare beneficiaries.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF = congestive heart failure.

Cost data are adjusted for area wages.

Source: Analysis of 2001 Medicare Standard Analytical Files (SAF) 5% Inpatient Data.

Similarly, this analysis found wide variations across hospital referral regions in Medicare's standardized costs and one-year survival rates for three major acute conditions: heart attack (AMI), colon cancer, and hip fracture (Commonwealth Fund Commission 2006). Medicare costs for AMI patients ranged from $31,413 in the tenth percentile region to $23,410 in the ninetieth percentile region—a difference of 34 percent between the highest- and the lowest-cost groups—with differences of 10 percent and 33 percent, respectively, for colon cancer and hip fracture. The variation between the tenth percentile and the ninetieth percentile across the regions in risk-adjusted mortality rates for the three conditions was even greater: a difference of 24 percent for AMIs, 68 percent for colon cancer, and 30 percent for hip fracture.

Using these data to identify those regions with both the lowest costs and the best outcomes (i.e., exceeding the seventy-fifth percentile on each measure) indicates that Medicare could save almost $900 million a year by paying a maximum global fee for all care of patients with AMIs, colon cancer, and hip fracture equal to the average standardized costs for the highest-performing regions (Commonwealth Fund Commission 2006). In addition, if all regions could achieve that level of performance on both costs and outcomes, almost 8,500 lives could be saved.

These findings suggest that Medicare could both cut costs significantly and have better outcomes if providers in all geographic areas of the country offered both the cost and the quality of the best-performing areas. Many factors account for these variations, such as differences in population characteristics, hospitals' readmission rates, supply of specialists, hospitals' capacity, and physicians' medical school and training. But if Medicare paid the same rate for all care of an acute condition or a single annual rate for the care of patients with a given set of chronic conditions and based the payment rate on that of the best-performing areas, it would be a powerful incentive for all providers to offer more efficient care. In any case, given the current twofold variations, a phased transition rewarding better performance and trimming payments to high-cost providers or geographic areas would be required to give providers time to adapt.

Appropriate measures must be developed and used to encourage and reward improvements in process and outcomes and to demonstrate that reduced costs can and should be accompanied by better quality. Several Medicare demonstrations are currently testing ways to change the negative financial incentives that providers now face, and these should show whether and how higher quality and reduced expenditures can be achieved simultaneously, as well as produce models that can be used to achieve these objectives.

Medicare Pay-for-Performance Demonstrations: What Can They Tell Us?

Medicare has begun testing models for rewarding quality and efficiency (CMS 2005a, 2005b; Guterman and Serber 2007). The two main ones are the Hospital Quality Incentive (HQI) Demonstration and the Physician Group Practice (PGP) Demonstration. The first one is concerned primarily with quality, and the second one is focused on efficiency, with some of the rewards contingent on meeting quality standards.

The HQI Demonstration was launched in October 2003, and participation was voluntary for the approximately 550 nonprofit hospitals in the Premier Perspective system. The members of this system are reporting on their own quality and efficiency and are sharing and comparing this information with their peers. As of January 2006, more than 255 hospitals were participating. In accordance with this demonstration, hospitals are rewarded for their performance on thirty-four process and outcome measures for hospital inpatients with one of five conditions: AMI, heart failure, pneumonia, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and hip and knee replacements. Data on these measures are posted on the Medicare website.

One study found that the participating hospitals raised their composite quality scores after one year, compared with those of nonparticipating hospitals, with an overall quality score improvement of 9.3 percent for the participating hospitals and 6.7 percent for nonparticipating hospitals (Grossbart 2006). Of the three conditions examined in the study, the rate of improvement in the management of heart failure patients improved substantially—19.2 percent for participating hospitals versus 10.9 percent for nonparticipating hospitals—but the improvement in the other two conditions (AMI and pneumonia) was statistically the same for the participating and nonparticipating hospitals. A study based on the first two years of the demonstration found significant but small (2.9 percent) improvements in the participating hospitals, compared with hospitals simply reporting quality results. Furthermore, those differences tended to be smaller when adjusted for baseline levels of performance for the individual hospitals (Lindenauer et al. 2007). Given the intense scrutiny of this demonstration, however, the participating hospitals may have made a greater effort to improve (the “Hawthorne effect”), which might not be replicated in a broader implementation. Nonetheless, because of the urgency of addressing the high cost of care and the wide variations in cost, a systematic social experimentation of different payment strategies is needed to reform Medicare's long-term payment policy (Epstein 2007).

The goals of the PGP Demonstration are to coordinate all Medicare services, encourage investment in administrative structure and process to increase efficiency, and reward physicians for improving health outcomes. The demonstration began in April 2005, but no data on its impact are yet available (CMS 2005a). Ten large, multispecialty physician-group practices, representing more than 5,000 physicians and more than 200,000 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, are participating in the demonstration. The growth of Medicare's expenditures for beneficiaries receiving most of their care from these group practices is being contrasted with that for other beneficiaries in the same areas. If Medicare's total spending on the patients assigned to the group practice grows more slowly, the practice will be eligible for a bonus, based on the amount of the savings and its ability to meet quality targets for preventing and managing chronic conditions.

At the end of the first year, the group practices convened to share their experiences and strategies. Before the demonstration started, all the participating sites had had experience managing care because they owned or had previously owned a managed care product or had a disease management contract with a managed care plan. Eight of the ten group practices are part of an integrated delivery system that owns its hospital, thereby facilitating the integration of care across all care sites. The practices are concentrating on four areas in which to save money: managing and better coordinating care; expanding palliative and hospice care; modifying physicians' practice patterns and behavior; and enhancing information technology (Trisolini et al. 2006). The initial results have been promising, but (as of April 2007) the bonus amounts for the first year have not yet been determined.

Both these demonstrations will be closely watched, as well as others that have been and are being launched. One of these, the Medicare Health Care Quality Demonstration Program mandated as part of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), will test major changes in system designs aimed at improving the quality of care while increasing efficiency. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has stated that it will choose from eight to twelve sites from the applications solicited in January and September 2006 (CMS 2006). This demonstration is directed at integrated health systems or coalitions of hospital and physician groups in a particular geographic area that are interested in joining with Medicare (and perhaps with other payers as well) to better coordinate the delivery of care.

Other demonstrations with promising uses of financial incentives to improve care for Medicare beneficiaries are the following: The Medicare Care Management Performance Demonstration, also mandated in the MMA, will give bonuses to solo and small- to medium-size physician practices in four states for improving their office systems and better managing Medicare patients with certain chronic conditions. The Physician-Hospital Collaboration Demonstration will examine whether sharing their gains improves the quality of care in a health delivery system. Finally, the Medicare Hospital Gainsharing Demonstration, mandated by the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, will test and evaluate arrangements between hospitals and physicians to improve the quality and efficiency of their beneficiaries' care, as well as various coordinated care initiatives to improve the treatment of Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions (Guterman and Serber 2007).

This array of initiatives has been and will continue to produce information that can be used to redesign Medicare payments to produce a better, more efficient health care system for its beneficiaries and for all Americans.

Reports by the Institute of Medicine

The U.S. Congress asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to make recommendations regarding the reform of Medicare payments in a way that would reward performance. Accordingly, the IOM's Committee on Redesigning Health Insurance Performance Measures, Payment, and Performance Improvement Programs issued a report in December 2005 calling for the creation of what is now the National Quality Coordination Board, in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, to establish a process for setting quality and efficiency metrics to be used in a pay-for-performance system, ensuring the collection of data on those measures of performance and coordinating with Medicare, Medicaid, and private payers to advocate their adoption (IOM 2006a). This report also cited measures that were ready to be incorporated in a pay-for-performance system and outlined a plan for the adjustment of these measures in the future.

Another report by the same IOM Committee, released in September 2006, contained recommendations for the structure of payment rewards (IOM 2006b). These are (1) creating a bonus pool largely from existing funds, by dedicating a portion of payments to be distributed to providers performing well on clinical quality, patient-centered care, and efficiency; (2) giving bonuses to both high performers and those showing improvement; and (3) reporting information about performance in ways that are both meaningful and understandable to providers and consumers. The report also recommended that Medicare beneficiaries be encouraged to find a principal source of care and that providers meeting the standards for assuming a care coordination role be paid for offering those services and rewarded for performing them well. The report also recommended allowing the system to evolve, so as provide comprehensive and longitudinal measures of provider and health system performance.

In recommending basing pay-for-performance on efficiency as well as quality, the IOM Committee defined efficiency as “achieving the highest level of quality for a given level of resources” (IOM 2006b, p. 25). It uses the definition of Medicare cost as the total use of Medicare-covered services for a patient with a given condition multiplied by “standardized” prices, which remove the effect of Medicare's allowances for teaching hospitals, disproportionate-share allowances, geographic practice-cost differences, and similar confounding factors. This changes the basis of payment from a “service-based rate” to a “case-based rate,” so that providers will be encouraged to focus on providing care over an episode or over time, rather than for individual encounters.

The IOM report noted the limited evidence base on pay-for-performance and issues surrounding the feasibility of implementation, the magnitude of rewards sufficient to influence provider behavior, and the possibility of unintended consequences (Fisher 2006; Fisher and Davis 2006). Given these considerable uncertainties, the IOM Committee recommended that implementation proceed gradually, first with public reporting and then with modest rewards based on a limited set of scientifically valid measures, and that at each stage the system be monitored and informed by an ongoing evaluation and timely information on the consequences, both intended and otherwise.

The IOM report also noted that modest pay-for-performance incentives are not a sufficient long-term answer to the many more perverse incentives presented by the current fee-for-service payment system. Ideally, pay-for-performance would be viewed as a transition to a new payment system that is based on episode or population or is a blend of fee-for-service and an episode-/population-based system. For example, the first phase for a pay-for-performance system could be designed with only a modest portion of total payment (e.g., 2 percent) based on top performance or improvement in quality and efficiency, followed by an intermediate phase with a more substantial payment (e.g., 10 percent) based on the achievement of some absolute level of quality and efficiency, followed by a blended payment system of episode-/population-based and fee-for-service rates (e.g., one-third of the total payment determined by episode-/population-based rates and two-thirds by fee-for-service rates). While the details of such a plan could be modified as experience is gained, it would provide a way of gradually moving toward a blended payment system while monitoring its impact.

Redesigning Medicare's Payment System to Reward Excellence and Efficiency

A blended payment system with mixed fee-for-service and capitation was first advocated by Newhouse (1986), but the payment system then in place was very different from what it is today: Medicare's prospective payment system for the operating costs of hospital inpatient services had begun to be implemented only in October 1983 and was still in the midst of a four-year transition period to full adoption. Hospital inpatient capital costs were not brought under prospective payment until October 1991, with a ten-year transition period that ended only in September 2001. The resource-based physician fee schedule was still more than five years away. In addition, Medicare's current prospective payment systems for hospital outpatient services, as well as those for inpatient rehabilitation facilities, psychiatric hospitals, long-term care hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and home health agencies, had not yet been developed. Moreover, both the mechanism for risk-adjusting capitated rates and the means for measuring quality and efficiency available today—although still far from perfect—are substantially more sophisticated than they were in the mid-1980s.

With the tools available today, we can build on the current payment system to place greater emphasis on quality and efficiency and move toward more fundamental change. Support is building for such broader approaches, as represented by the receptive positions of some major professional organizations regarding the concept of a per-patient payment for physicians serving as the patient's “medical home” (Tooker 2006). In addition, the National Quality Forum—a not-for-profit organization created to develop and implement a national strategy for measuring and reporting health care quality—has begun to focus on assessing value across episodes of care (National Quality Forum 2007).

A key issue in moving from today's system, which emphasizes the individual provider, to a more coordinated system is how rewards for the joint provision of care over an episode or care for a patient with a particular chronic condition would be distributed among independent physicians, hospitals, and other facilities. As noted earlier, there are at least four ways of allocating rewards across providers: (1) payment to an integrated delivery system or multispecialty group practice; (2) payment to new organizational entities such as physician-hospital organizations or networks of independent physician practices; (3) payment that rewards all providers in a geographic area (e.g., a hospital referral region), based on the performance of the region as a whole; and (4) some other rules for distributing rewards among providers jointly providing care (e.g., in proportion to the provider's share of charges).

In many ways, the integrated delivery system or multispecialty group practice is an ideal model of coordinated care. In this model, the provider is financially responsible for the entire care of its patients. Medicare currently, however, does not recognize integrated delivery systems or multispecialty group practices as a provider class with its own payment rules. For example, such practices could be paid a capitation based on the population served, all-inclusive acute episode case rates, and bonuses for excellence on quality. At the present time, integrated delivery systems and large group practices represent only a small minority of all patient care. But if the pay-for-performance design were attractive to practices showing that they could offer the integrated care that their patients need, more physicians might be encouraged to develop that capacity, either by participating in integrated systems or multispecialty group practices or by devising other ways of integrating actually or virtually to meet their patients' needs.

Payments to physicians not practicing in an integrated delivery system might be based on experience in a geographic area. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission suggested basing pay-for-performance rewards on performance in a particular geographic area. For example, the current reduction in physician fees, required by legislation under what is known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, could be waived in geographic areas where the total costs per beneficiary are lower than the national median. Since the rationale for the SGR was a national expenditure target that would discourage excessive use by tying fee increases to performance on total outlays, this would effectively move the SGR to the local area, where providers accountable for variations in use and cost would be more closely linked. The disadvantage would be rewarding providers that do not contribute to the higher performance in a given geographic area and penalizing providers that perform well but are in a geographic area that does not. But the advantage would be to support regional efforts to improve overall performance and to encourage providers to be more mindful of their referral patterns and the implications for local spending levels.

Finally, payments for physicians' inpatient services could be linked to hospitals' performance on quality and efficiency. For example, if a hospital offered better quality and lower total costs for hip replacement patients, bonuses could be distributed not only to the hospital (as they are under the HQI Demonstration) but also to the physicians caring for those patients, in proportion to their share of the total charges.

All these options are worthy of further testing. The first and last options build on Medicare's experience with its demonstrations and thus might be the easiest to implement because they do not require creation of new physician-hospital organizations. They could begin on a voluntary basis, as the current demonstrations do, thereby allowing the approaches to be tested in a more receptive environment.

One question is whether to wait until more demonstration experience is gained and early results are confirmed before changing payments further. The drawback to waiting for the evaluations is that they often are not available for several years after a demonstration has been completed. The experience to date with the HQI Demonstration and the PGP Demonstration confirms that they are feasible to implement, and the process evaluations and preliminary data indicate that they are having the desired effect. Building on this experience with a gradual rollout to additional providers should create an even larger evidence base and begin to address the wide variations in current performance. In an increasingly constrained budget environment as the baby boom generation reaches retirement, failing to act also runs the serious risk of undermining the Medicare program's solvency, thereby reducing beneficiaries' health and economic security and/or having to increase taxes to support the program.

In any event, such a pay-for-performance payment system must be carefully constructed, phased in gradually, monitored closely, and modified as experience is gained. Ultimately, matching such a payment system with clinical guidelines on the appropriate treatment for different conditions could help determine “quality-adjusted” cases of care.

Unlike the commercial products for measuring efficiency, it is important that any Medicare payment system be completely transparent, so that everyone can see both the methods and the actual data on which the rewards are based. Because constructing such a system will be complicated and take time to get right, the data on which bonuses will be based should be fed back to providers, and the initial bonuses should offer only modest incentives. But the ultimate result of a blended payment system based on both fee-for-service, which rewards productivity, and population or episode case rate payments, which reward the prudent use of resources, would go a long way to rewarding the results we would like to achieve and narrow the current wide, and unacceptable, variations in both quality and efficiency.

Conclusions

The emerging interest in pay-for-performance methods of paying providers—if those systems are designed wisely and implemented carefully—shows considerable promise for using financial incentives to reward the kind of care that physicians would like to give their patients and that their patients would like to receive, in a way that uses economic resources prudently. Any payment reform faces formidable political obstacles. Beginning with “upside” rewards, however, is more palatable and is an opportunity to become acquainted with the new payment system and gives time and opportunities for providers to adapt to it.

Pay-for-performance could be used to encourage improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care by emphasizing better and more effective care, rather than the increasing volume and complexity of care that the current payment system encourages. Pay-for-performance would reduce the wide variation across the United States in spending and outcomes for patients with the same conditions. Most important, such a payment system could be used to reward the coordination of care across providers and sites of care (Davis 2007).

Medicare could be a model for private payers that are now creating their own approaches to rewarding excellence and efficiency. Payment reform could take place in two stages: a pay-for-performance payment system with bonuses for excellence of care and efficiency, followed by a blended fee-for-service and capitated case-rate payment system for managing patients with chronic conditions and case rates for episodes of acute care.

Medicare's recognition of qualifying integrated delivery systems and multispecialty group practices as participating Medicare providers would offer accountability for the care of patients over time and better coordination of their care, by supplementing the current designation of hospitals and physicians as Medicare providers under the fee-for-service program. The difficult work will be not just realigning financial incentives but restructuring the delivery of care and organizing health care services in a way that best capitalizes on these incentives. Establishing an attractive payment system that matches the providers' interests with high-quality, efficient care may facilitate the growth of such systems of care.

We are seeing movement in the right direction in a variety of initiatives in both the public and the private sectors. As a group of key health policy leaders stated in an open letter on the importance of Medicare's leadership on pay-for-performance: “The available measures are less than perfect, but … we have the adequate tools to accelerate the pace of change” (Berwick et al. 2003, p. 9). With a concerted effort, the care of both Medicare beneficiaries and the health system can be improved.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Cathy Schoen and Stephen C. Schoenbaum, MD, for their helpful comments; Gerard Anderson, PhD, for tabulations from the 2001 Medicare Standard Analytical Files (SAF) 5 percent Inpatient Data; Elliot S. Fisher, MD, for tabulations of Dartmouth Atlas data from a 20 percent national sample of Medicare beneficiaries; and Alyssa L. Holmgren for her research assistance.

References

- Berwick DM, DeParle N, Eddy DM, Ellwood PM, Enthoven AC, Halvorsen GC, Kizer KW, McGlynn EA, Reinhardt UE, Reischauer RD, Roper WL, Rowe JW, Schaefer LD, Wennberg JE, Wilensky GR. Paying for Performance: Medicare Should Lead. Health Affairs. 2003;22(6):8–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlin A, Cowan C, Heffler S, Washington B National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National Health Spending in 2005: The Slowdown Continues. Health Affairs. 2007;26(1):142–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Begins Performance-Based Payments for Physician Groups (January 31) [accessed December 5, 2005]. Available at, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/researchers/demos/PressRelease1_31_2005.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Demonstration Shows Hospital Quality of Care Improves with Payments Tied to Quality (November 14) [accessed December 19, 2005]. Available at, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/release.asp?Counter=1729.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Demonstrations (November 16) [accessed October, 24, 2006]. Available at, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/MD/list.asp#.

- Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System. Why Not the Best? Results from a National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2006. September. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Fact Sheet for CBO's March 2007Baseline: MEDICARE. [accessed March 22, 2007]. Available at, http://www.cbo.gov/budget/factsheets/2007b/medicare.pdf.

- Davis K. Rewarding Excellence and Efficiency: What Does It Mean and How to Get There? Harry Kimball lecture, American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, July 30.

- Davis K. Paying for Care Episodes and Care Coordination. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(11):1166–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AM. Pay for Performance at the Tipping Point. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(5):515–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ES. Paying for Performance: Risks and Recommendations. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(18):1845–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ES, Davis K. Pay for Performance: Recommendations of the Institute of Medicine. Audio Interview. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(13):e14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ. Variations in the Longitudinal Efficiency of Academic Medical Centers. [accessed December 12, 2005];Health Affairs. 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.19. Web Exclusive (October 7). Available at, http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.var.19v1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. Private Plans in Medicare: A 2007 Update. Menlo Park, Calif: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. March. [Google Scholar]

- Grossbart SR. What's the Return? Assessing the Effect of “Pay-for-Performance” Initiatives on the Quality of Care Delivery. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63(1):26S–48S. doi: 10.1177/1077558705283643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M. The Demand for Health: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation. New York: Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Guterman S, Serber M. Enhancing Value in the Medicare Program: Demonstrations and Other Initiatives to Improve Medicare. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2007. February. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Interactive. The Commonwealth Fund Health Opinion Leaders Survey. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2005. July. [Google Scholar]

- Hornbrook MC. Definition and Measurement of Episodes of Care in Clinical and Economic Studies. In: Grady ML, Weis KA, editors. Cost Analysis Methodology for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. pp. 15–40. AHCPR Publication no. 95-0001. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Performance Measures: Accelerating Improvement. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Rewarding Provider Performance: Aligning Incentives in Medicare. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Fact Sheet: Medicare Advantage (March) [accessed March 23, 2007]. Available at, http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/2052-09.pdf.

- Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, Rothberg MB, Benjamin EM, Ma A, Bratzler DW. Public Reporting and Pay for Performance in Hospital Quality Improvement. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(5):486–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis SM, Rogowski JA, Escarce JJ. The Managed Care Backlash: Did Consumers Vote with Their Feet? Inquiry. 2004;41(4):376–90. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_41.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) Report to the Congress: Increasing the Value of Medicare (June) [accessed August, 8, 2006]. Available at, http://www.medpac.gov/publications/congressional_reports/Jun06_EntireReport.pdf.

- National Quality Forum. Establishing Priorities, Goals and a Measurement Framework for Assessing Value across Episodes of Care. [accessed March, 25, 2007]. Available at, http:/www.qualityforum.org/projects/ongoing/priorities.

- Newhouse JP. Rate Adjusters for Medicare under Capitation. Health Care Financing Review. 1986:45–55. annual suppl. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, Ash AS, Ayanian JZ, Lezzoni LI, Ingber MJ, Levy JM, Robst J. Risk Adjustment of Medicare Capitation Payments Using the CMS-HCC Model. Health Care Financing Review. 2004;25(4):119–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Competition in Health Care. Harvard Business Review. 2004;82(6):65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MB, Landon BE, Normand S-L, Frank RG, Epstein AM. Pay for Performance in Commercial HMOs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(19):1895–1902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JW. Pay-for-Performance and Accountability: Related Themes in Improving Health Care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:695–99. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-9-200611070-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen C, Davis K, How SKH, Schoenbaum SC. U.S. Health System Performance: A National Scorecard. Health Affairs. 2006. [accessed March, 22, 2006]. Web Exclusive (September 20). Available at, http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff/cgi/reprint/25/6/w457.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Skinner JS, Staiger DO, Fisher ES. Is Technological Change in Medicine Always Worth It? The Case of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Health Affairs. 2006. [accessed November, 28, 2006]. Web Exclusive (February 7). Available at, http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.25.w34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tooker J. The Advanced Medical Home: A Patient-Centered, Physician-Guided Model of Health Care. Presentation at the Alliance for Health Reform/Commonwealth Fund Forum on Strengthening Adult Primary Care: Models and Policy Options, October 3.

- Trisolini M, Pope G, Kautter J, Aggarwal J. Medicare Physician Group Practices: Innovations in Quality and Efficiency. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2006. December. [Google Scholar]