Abstract

Context

States have long lobbied to be given more flexibility in designing their Medicaid programs, the nation's health insurance program for the low-income, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. The Bush administration and the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 have put in place policies to make it easier to grant states this flexibility.

Methods

This article explores trends in states' Medicaid flexibility and discusses some of the implications for the program and its beneficiaries. The article uses government databases to identify the policy changes that have been implemented through waivers and state plan amendments.

Findings

Since 2001, more than half the states have changed their Medicaid programs, through either Medicaid waivers or provisions in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. These changes are in benefit flexibility, cost sharing, enrollment expansions and caps, privatization, and program financing.

Conclusions

With a few important exceptions, these changes have been fairly circumscribed, but despite their expressed interest, states have not yet fully used this flexibility for their Medicaid programs. However, states may exercise this newly available flexibility if, for example, the nation's health care system is not reformed or an economic downturn creates fiscal pressures on states that must be addressed. If this happens, the policies implemented during the Bush administration could lead to profound changes in Medicaid and could be carried out relatively easily.

Keywords: Medicaid, Medicaid reform, Medicaid waivers, Deficit Reduction Act of 2005

Medicaid is the nation's major public financing system that provides health care coverage to low-income families, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Started in 1965, Medicaid is an open-ended funding program in which the federal government and states share the cost of health insurance for beneficiaries so long as the states meet specific eligibility and benefit requirements. Within broad federal guidelines, states design their own Medicaid programs. Each state, for example, determines who will be eligible for coverage, what services will be covered, and how much providers will be paid for rendering care to Medicaid beneficiaries. In 2006, combined federal and state expenditures on the program totaled more than $314 billion, and Medicaid accounted for 15 percent of the nation's total spending on health (CMS 2006). About 60 million Americans received some Medicaid coverage during 2006 (Ellis et al. 2007).

Over the last several years, virtually every dimension of Medicaid has been affected by changes that states have implemented. Among other things, various states have reduced or eliminated Medicaid benefits, capped program enrollment, and imposed premiums and other costs on beneficiaries. At the same time, though, a few states have extended Medicaid to groups that had previously not been eligible for the program, such as childless adults. Some states have also broadened the role of the private marketplace in Medicaid by expanding managed care programs and offering premium assistance programs. Moreover, beginning in the early 1990s, many states maximized federal Medicaid funds while reducing their share of matching contributions. But at the urging of the federal government, some states are now financing Medicaid differently and are now more likely to use actual state or local outlays to cover their share of program expenditures.

Many of these recent changes were brought about not through legislation but through waivers of federal requirements. Medicaid waivers allow the federal government, as a long-standing statutory authority, to permit states to alter their programs in ways not otherwise allowed under federal Medicaid law. These recent state Medicaid waivers cover a wide variety of initiatives, ranging from shifting beneficiaries to managed care, to expanding eligibility, to changing how payments to hospitals are made.

In addition, in February 2006, President George W. Bush went beyond using the traditional waiver process to reshape Medicaid when he signed the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which included provisions granting states additional freedom in designing their Medicaid programs. The DRA also included provisions allowing states to make changes in their programs more expeditiously than had previously been allowed (Rosenbaum and Markus 2006; Rudowitz and Schneider 2006).

In this article, we explore some of the recent Medicaid policies that states have adopted and discuss some of the implications that they have had for the program and its beneficiaries. We consider changes in Medicaid related to benefit flexibility, cost sharing, enrollment expansions and caps, privatization, and program financing. Given the multitude and scope of the changes, our analysis is not exhaustive, but we have highlighted some of the more important ways in which Medicaid has been reshaped.

Background

Using waivers to change the Medicaid program has been a major state health policy option under the Bush administration. Between 2001 and 2006, for example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency charged with administering Medicaid, approved Section 1115 waivers from over two-thirds of the states (Thompson and Burke 2007).1 Even though Medicaid waivers have been used in the past, the Bush administration's waiver policies represent a departure in that they have not only simplified the federal approval process that states must follow to secure a waiver but also have granted states unprecedented program flexibility.

For several years, states have sought more freedom in the design of their Medicaid programs. For example, they have argued that health care is a local matter and that they, not federal policymakers, are better able to understand their particular problems and thus are in a better position to craft efficient, effective health care programs that will meet the needs of their residents. States also maintain that allowing flexibility will promote innovation and improvement in the Medicaid program, which will lead other states to follow. And states reason that by letting them experiment in testing new strategies, they will produce much needed information about what does and does not work. Not only will this help guide other states in their reform efforts, but it also will enhance national discussions of health care.

Critics, however, charge that if granted more authority in setting Medicaid policy, states, rather than behaving as laboratories of innovation, will pursue short-term goals (e.g., cost containment), which may end up harming the welfare of the program's beneficiaries. Another argument against allowing more state flexibility is that it will only worsen the persistent inequities resulting from state-to-state variations in the program's benefits, eligibility standards, and spending (Holahan 2003).

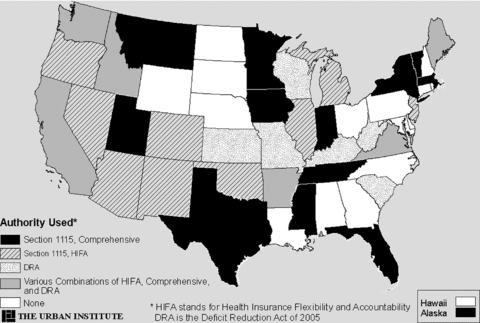

Since 2001, thirty-five states have made changes in their Medicaid programs through either the 1115 waivers or one of the new Medicaid DRA provisions. Figure 1 summarizes these changes. While many are modest, others represent fundamental and important alterations to the Medicaid program. States have altered Medicaid by three main means: comprehensive section 1115 waivers, the Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability (HIFA) waiver initiative, and the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005.

Figure 1.

State Medicaid Policy Changes Made through Medicaid Section 1115 Waivers and DRA, 2001–2008

Section 1115 Waivers

Comprehensive Section 1115 Waivers

The Bush administration promoted comprehensive waivers to allow states to reform their Medicaid programs. Accordingly, these section 1115 Medicaid waivers have enabled states to make a wide assortment of financing and delivery changes, including revamping the financing of “safety-net” hospitals, shifting away from guaranteeing beneficiaries specific benefits, and capping federal Medicaid spending. Florida, Iowa, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont have proposed some of the more prominent comprehensive waivers that were recently approved.

Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability

One of the Bush administration's early Medicaid initiatives was the Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability (HIFA) demonstration waiver policy, a type of section 1115 waiver that was introduced in August 2001. With the goal of making the waiver process quicker and easier, the HIFA initiative gave states flexibility to change their Medicaid programs in ways not previously allowed. Specifically, the HIFA permits states to experiment with alternative coverage strategies and eligibility rules. Under the HIFA, states can, for example, impose caps on enrollment, modify benefit structures (e.g., provide different benefit packages to different populations within Medicaid), and increase beneficiaries' cost sharing.

In exchange for this new flexibility, states must expand their health insurance coverage, especially for individuals with incomes less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line. When expanding this coverage, states are expected to emphasize private-market approaches by means of premium assistance programs, which use federal and state Medicaid or State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) funds to subsidize the purchase of health insurance. As of March 2008, the CMS had approved waivers for HIFA demonstrations in fourteen states.

Deficit Reduction Act of 2005

The Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005 contains several provisions giving states new authority to make changes in their Medicaid programs. Designed in large part to reduce federal Medicaid spending, the DRA provides, among other things, new program flexibility.2 In particular, the DRA gives states the ability to require certain beneficiaries to pay premiums and to share costs. In lieu of the standard Medicaid benefit package, the DRA also allows states to offer beneficiaries a “benchmark benefit coverage” package. This package must offer services covered under the standard Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan offered to federal employees, a benefit plan for state employees, the largest commercial HMO in the state, or an option approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The DRA also allows for up to ten states to open Health Opportunity Accounts (HOAs), which are modeled on health savings accounts. The HOAs permit states to establish accounts for beneficiaries to pay for medical care services. Then if the beneficiaries exhaust their HOA, states can impose cost sharing on them before they are permitted to receive regular Medicaid benefits. As of 2008, ten states had amended their Medicaid programs through DRA provisions (CMS 2008a).

Another important DRA provision allows states to make many of these changes by simply amending their state Medicaid plans, whereas previously they would have required a waiver to make such modifications.3 Compared with obtaining a waiver, amending a state Medicaid plan is more straightforward and quicker (Rudowitz and Schneider 2006) and usually is subject to less review by federal officials.

Highlights of Recent Trends in Medicaid

Table 1 lists those states that have made changes in their Medicaid program through section 1115 and HIFA waivers since 2001 and the types of changes that they have introduced. In total, thirty-three new waivers and amendments to existing waivers were approved by the Bush administration between 2001 and 2008. Specifically, the states sought to gain benefit flexibility (17 states), introduce premiums and cost sharing (23 states), expand eligibility for coverage (24 states), cap enrollment (11 states), integrate market principles into the program (23 states), and revamp program financing (9 states). Next we discuss each of these types of reforms in more detail and present examples of states that brought them into their Medicaid programs.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Selected Section 1115 and HIFA Waivers to State Medicaid and SCHIP Programs, 2001–2007

| Official Waiver Name | State | Waiver Type | Year of Approval | Benefit Flexibility | Premium or Cost Sharing | Coverage Expansions | Enrollment Caps | Market Principles | Revamping Financing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denali KidCare | Alaska | 1115 | 2004 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Arizona HIFA Amendment | Arizona | HIFA | 2001 | No | Yes | Yes | No1 | Yes | No |

| Arkansas Safety Net Benefit Program | Arkansas | HIFA | 2006 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Arkansas TEFRA-Like 1115 Demonstration | Arkansas | 1115 | 2002 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| California Parental Coverage Expansion | California | HIFA | 2002 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| MediCal Hospital/Uninsured Care | California | 1115 | 2005 | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Amendment to Adult Prenatal Coverage in CHP+ | Colorado | HIFA | 2002 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| District of Columbia 1115 for Childless Adults | District of Columbia | 1115 | 2002 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Florida Medicaid Reform | Florida | 1115 | 2005 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| New MEDS-AD Program | Florida | 1115 | 2005 | No | No | Yes2 | No | No | No |

| Idaho Children's Access Card | Idaho | HIFA | 2004 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| KidCare Parent Coverage | Illinois | HIFA | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Healthy Indiana Plan | Indiana | 1115 | 2007 | Yes3 | Yes | Yes3 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IowaCare | Iowa | 1115 | 2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| MaineCare for Childless Adults | Maine | HIFA | 2002 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MassHealth | Massachusetts | 1115 | 2005 | No4 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Adult Benefits Waiver | Michigan | HIFA | 2004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| MinnesotaCare Section 1115 | Minnesota | 1115 | 2001 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Healthier Mississippi | Mississippi | 1115 | 2004 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Montana Basic Medicaid for Able Bodied Adults | Montana | 1115 | 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Nevada HIFA Demonstration | Nevada | HIFA | 2006 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Families and Pregnant Women | New Jersey | HIFA | 2003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| State Coverage Initiative Program | New Mexico | HIFA | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| New York Partnership Plan | New York | 1115 | 2001 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| New York Federal-State Health Reform Partnership | New York | 1115 | 2006 | No | No | No5 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Oklahoma Employer/Employee Partnership for Insurance Coverage | Oklahoma | HIFA | 2005 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Oregon Health Plan | Oregon | HIFA | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| TennCare II | Tennessee | 1115 | 2002 | Yes | Yes | No6 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Texas Children's Health Insurance Program Cost Sharing Waiver | Texas | 1115 | 2007 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Primary Care Network | Utah | 1115 | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Global Commitment to Healthcare | Vermont | 1115 | 2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| FAMIS MOMS/FAMIS Select | Virginia | HIFA | 2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Washington Premium Proposal | Washington | 1115 | 2004 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Total Number of Waivers: 33 | Total in Category: | 17 | 23 | 24 | 11 | 23 | 9 | ||

No enrollment cap but an expenditure cap is imposed and limited by available SCHIP funds. Medicaid funds are available as backup financing for some expansion groups.

Extends coverage to disabled and aged people under 88 percent FPL whom the legislature removed from the State Plan in 2005.

Indiana instituted Healthy Indiana Plan, a high-deductible health savings account type plan for the expansion population of adults up to 200 percent FPL. The original Medicaid population remained in the managed care Medicaid program.

There are separate packages for undocumented immigrants and limited services for pregnant women who self-declare income below 200 percent FPL.

The federal government provides money for the Medicaid reforms (such as implementing EMR, reducing reliance on acute care hospitals), which frees up state funds to be used for programs that cover uninsured populations.

Tennessee's waiver disenrolled individuals from selected groups and then reopened eligibility to selected groups.

Note: The approval date refers to the initial date of approval. Many waivers had subsequent amendments (not shown).

Ten states have taken advantage of the DRA provisions allowing for benefit flexibility regarding covered services. Four states—Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, and West Virginia—moved quickly and put in place their state plan amendments in 2006. Besides incorporating greater benefit flexibility, Kentucky's DRA amendment offers premium assistance to encourage beneficiaries to enroll in employer-sponsored health insurance coverage. Those states that obtained approved DRA amendments in 2007 and early 2008 are Maine, Missouri, South Carolina, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. To date, South Carolina is the only state to use the Health Opportunity Account provision of the DRA. At least initially, South Carolina plans to offer the HOA option on a limited basis: up to one thousand beneficiaries in a single county will be eligible to enroll in the initiative, which is scheduled to be implemented in spring 2008.

Benefit Flexibility

The basic Medicaid benefit package is broad, and states can also choose from a range of optional benefits, thereby making the package not only flexible but also highly variable across states (table 2). Until recently, however, federal rules governing Medicaid mandated that all enrollees be eligible for all the services (both mandatory and optional) a state offered, a provision that many states viewed as unnecessarily restrictive and costly. Through waivers and the DRA, several states have sought the ability to vary the benefit package across the subgroups (e.g., the disabled, adults, and children) within their Medicaid populations (NGA 2005).

TABLE 2.

Mandatory and Optional Services and Populations in the Medicaid Program

| Mandatory Services and Populations Generally Required | Commonly Covered Optional Services and Populations | |

|---|---|---|

| Services | •Physician services | •Prescription drugs |

| •Hospital services (inpatient and outpatient) | •Clinic services | |

| •Laboratory and X-ray services | •Dental and vision services | |

| •Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment (EPSDT) services for individuals under 21 | •Physical therapy and rehab services | |

| •Medical and surgical dental services | •TB-related services | |

| •Rural and federally qualified health center services | •Primary care case management | |

| •Family planning | •Nursing facility services for individuals under 21 | |

| •Pediatric and family nurse practitioner services | •Intermediate care facilities for individuals with mental retardation (ICF/MR) services | |

| •Nurse midwife services | •Home- and community-based care services | |

| •Nursing facility services for individuals 21 and older | •Personal care services | |

| •Home health care for persons eligible for nursing facility services | •Hospice services | |

| Populations | •Pregnant women with income up to 133% of poverty | •Parents, children, and pregnant women with income above mandatory levels |

| •Children under 6 up to 133% of poverty | •“Medically needy” individuals who have high medical costs relative to their income | |

| •Children aged 6 to 18 up to 100% poverty | •Elderly and persons with disabilities up to 100% of poverty | |

| •Parents with income below states' July 1996 welfare eligibility levels | ||

| •Elderly and persons with disabilities receiving Supplemental Security Income |

Although the CMS has granted considerable benefit flexibility to states through waivers during the Bush administration, it has been largely limited to enrollees that states are not required to cover under federal Medicaid law, for example, enrollees with high medical expenses relative to their incomes or individuals who qualify for Medicaid as an optional eligibility group. By and large, enrollees whom states are required by federal law to cover if they participate in Medicaid (e.g., parents and children receiving cash assistance, poor and near-poor children, and pregnant women) will continue to receive the full Medicaid package even with the new flexibility.

For certain subgroups of enrollees, however, some states have eliminated or limited coverage of optional services (e.g., dental care, chiropractic care, and substance abuse services). Among the HIFA waiver states, for example, New Jersey and Oregon have cut benefits for existing optional enrollees. Under a Section 1115 waiver, Utah also reduced certain benefits (e.g., some dental services) for some mandatory enrollees in order to generate enough savings to finance an expansion of coverage.

In its 1115 waiver, Florida did not directly reduce benefits but instead gave Medicaid managed care plans a significant role in determining the benefit package for adults. Although required to offer all mandatory benefits, the plans may decide which optional benefits to provide, subject to state approval. Benefit packages, however, must be “actuarially equivalent” to Florida's pre-waiver Medicaid benefit package for the average adult; that is, the estimated value of the new benefit package must be comparable to that of the pre-waiver Medicaid package. In addition, Florida beneficiaries can use their risk-adjusted premium to purchase employer-sponsored or individual health coverage; the state imposes no benefit requirements on this coverage.

Those states that have used the DRA provision allowing for more flexible benefit packages are West Virginia, Kansas, Kentucky, and Idaho. West Virginia, for example, offers to beneficiaries who receive financial assistance under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program a basic benefit package that includes mandatory Medicaid services. Specifically, beneficiaries can sign an agreement under which they will receive enhanced benefits focusing on age-appropriate wellness, chemical dependency, and mental health services, but only if they obtain screenings, keep appointments, and follow medical advice.

Also through DRA provisions, Idaho, Kentucky, and Kansas developed a variety of benefit packages for targeted populations. For example, Idaho created its Basic Benchmark Benefit Package for children and working-age adults, which excludes some services (e.g., certain mental health benefits), and its Enhanced Benchmark Benefit Package for individuals with disabilities, which includes all Medicaid services offered by the state before passage of the DRA. Kentucky requires most children enrolled in Medicaid and SCHIP to select a Family Choices benefit package based on, but not identical to, the state's state employee health benefit plan. Interestingly, Idaho's and Kentucky's plans include a provision allowing individuals who sign up for a limited package to be shifted to a broader plan if they later need other services.

Some states used the DRA benefit flexibility for more targeted purposes. For example, Kansas's waiver offers services (e.g., personal care services) tailored to the needs of workers with disabilities who are eligible to buy Medicaid coverage by paying a premium that covers a share of the program's costs. In addition, Washington and Virginia used the DRA to apply the benchmark benefits option only to beneficiaries with certain chronic conditions so that they could add disease management services to Medicaid.

While states have generally limited using this flexibility for beneficiaries already covered under the program, they have been more willing to use this benefit flexibility for coverage offered to expansion populations. A few states (e.g., Iowa, Michigan, and Utah) have expanded coverage as part of their waivers. Utah, for instance, offers newly eligible adults a limited package covering only primary and preventive care services and not inpatient hospital care or specialty care. Michigan and Iowa waivers also offer restricted benefits to expansion enrollees.

States have not aggressively used this benefit flexibility for several reasons. They may realize that offering different benefit packages to different populations would introduce administrative complexity into an already complicated program and would present administrative challenges for health care providers to keep track of which patients receive which benefits.

States may also recognize that using benefit flexibility to limit rarely used services would not save much money. For example, if states used their benefit flexibility to restrict long-term care services for nondisabled children, the savings would be minimal. Instead, to realize substantial program savings, states would need to reduce costly benefits (e.g., inpatient hospital care or prescription drugs), not optional services (e.g., speech therapy or dental care), which are the ones that so far have been cut. Eliminating more essential services, however, could have important health care consequences, as research suggests that restricting benefits can lower health status and end up increasing the use of more expensive health care services (Soumerai 2004; Soumerai et al. 1987, 1991, 1994; Tamblyn et al. 2001).

Reducing key benefits would also put greater pressure on safety-net providers, as low-income individuals needing uncovered services would likely still seek care. Thus, the net effect of reducing the scope of benefits may simply be to shift the costs from Medicaid, which shares its costs with the federal government and the states, and instead have the states, local areas, and private insurers shoulder the entire burden. Also, if benefits were cut sharply or the package offered was too restrictive, individuals might be less likely to view Medicaid as essential and either not enroll or allow their enrollment to lapse. This too would further stress the health care safety net that serves the low-income population.

Cost Sharing

Beneficiaries can be asked to share costs through premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments. Before passage of the DRA, however, unless a state obtained a waiver, Medicaid rules limited how much enrollees could be required to contribute to their health coverage. For example, the states could not impose premiums on most enrollees, including disabled beneficiaries, children, and pregnant women. Medicaid law also prohibited other types of cost sharing for certain groups and services, and when cost sharing was allowed, only nominal amounts were permitted (e.g., $2 per prescription or per visit). Finally, providers generally were required to provide a service even if an enrollee was not able to pay his or her cost share.

Under the DRA, states can now simply submit state plan amendments to impose premiums and cost sharing on those enrollees with incomes above 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), and cost sharing on enrollees with incomes above 100 percent of the FPL. For neither group, however, can the aggregate payments exceed 5 percent of family income.

Cost sharing is intended to give consumers a financial stake in their health care decisions in the hope that they will make wiser health choices, use care more appropriately, and, in the process, reduce Medicaid costs. Indeed, research suggests that health care use and costs decline when cost sharing is imposed (Lohr et al. 1986; Newhouse 2004). As we later discuss, there may be other effects as well.

As with benefit flexibility, on the whole states have not sought extensive cost-sharing flexibility. Of those states with HIFA waivers and those with comprehensive 1115 waivers, most did not alter cost sharing for their current enrollees. For example, even with the dramatic changes under its waiver, Florida maintained cost sharing at pre-waiver levels. As of this writing, states that made plan amendments through the DRA have not sought to modify their cost-sharing policies.

One important exception to this general trend is Oregon, which through its HIFA waiver opted to impose considerable cost sharing on certain enrollees rather than scale back benefits (Coughlin et al. 2006). In 2003, Oregon increased the premiums for adults based on income and tightened its premium payment policies. It also increased copayments for several services, some to fairly significant levels for low-income people (e.g., surgical services [$20], ambulance services [$50], and inpatient hospital services [$250]).4

A few states that broadened coverage under their waivers have used cost sharing more extensively for their expansion enrollees, mirroring the more limited benefit package offered to these newly covered groups. States in this category are Arizona, New Mexico, and Michigan. New Mexico, for example, made no changes to the cost-sharing structure of its current Medicaid enrollees but is charging its expansion enrollees (who are offered completely separate coverage) income-adjusted premiums and copayments.

For their existing enrollees, therefore, states have generally not used the new flexibility for cost sharing. But when states have turned to cost sharing, they have applied it to higher-income enrollees who can more easily afford to pay for some of their health care. States have avoided imposing cost sharing on lower-income enrollees and those with chronic illnesses. The reasons are that research evidence shows that even modest amounts of cost sharing may have harmful health effects on these populations because they tend to reduce equally their use of both appropriate and inappropriate care (Lohr et al. 1986; Newhouse 2004; Soumerai 2004; Tamblyn et al. 2001). Similarly, charging only higher-income beneficiaries for premiums is consistent with research showing both that participation in public insurance programs declines as premiums increase as a share of income and that higher premiums in public insurance programs are associated with a higher probability of being uninsured (Artiga and O'Malley 2005; Hadley et al. 2005; Ku and Coughlin 1999; Shenkman et al. 2002; Wright et al. 2005).

Coverage Expansions and Enrollment Caps

Most recently approved 1115 waivers included some planned (but not always implemented) coverage expansion, and as mentioned earlier, those states with HIFA waivers were expected to expand their coverage. New York's 2001 amendment to its Partnership Plan, for example, broadened the share of parents and childless adults who were eligible for public coverage from about 13 percent to 35 percent of the state's population (Long, Graves, and Zuckerman 2007). This large expansion in eligibility led to an increase in enrollment of almost 500,000 adults between 2001 and 2005. Iowa's waiver allowed the state to cover low-income adults as well as low-income children who are seriously emotionally disabled and living in the community. Massachusetts's 1115 waiver, which ultimately became part of the state's broader health care reform, expanded its Medicaid (MassHealth) coverage by extending income eligibility to some categories already eligible as well as adding some newly eligible groups, such as childless adults (MMPI 2005).

Under HIFA, higher-income parents and childless adults have been the two major expansion groups. The size of the planned coverage expansions under HIFA greatly varies among states. For example, Illinois is authorized to extend coverage to more than 300,000 parents with incomes up to 185 percent of FPL, and New Jersey's HIFA waiver covers a maximum of 12,000 parents with incomes less than 200 percent of FPL. Under HIFA, individuals who were previously covered under a state-financed health program could be counted as expansion enrollees. For example, before the demonstration was implemented, the 60,000 individuals in Michigan's HIFA expansion population had received some health services through a state-only program. Likewise, HIFA expansion populations in the Arizona, Illinois, and Oregon demonstrations include individuals who had been previously enrolled in state-funded health programs. Furthermore, although some HIFA waivers called for significant enrollment expansions many have fallen well short of their projected coverage goals (Coughlin et al. 2006).

While some states expanded coverage, others cut eligibility under recent waiver initiatives or plan amendments. For example, under a Section 1115 waiver amendment, Tennessee was given authority to disenroll up to 323,000 optional and expansion beneficiaries from TennCare, the state's long-running Section 1115 demonstration program. In August 2005, Tennessee began disenrolling about 200,000 of these persons. Idaho also used its DRA plan amendments to limit the eligibility of beneficiaries seeking coverage for Medicaid's long-term care, by adopting stricter rules related to asset transfers.

Some states have resisted explicit cuts in eligibility standards and instead have sought relief from the program's entitlement, which guarantees that all persons eligible to enroll in Medicaid can do so. Mirroring what is permitted under SCHIP, many of the recently approved Medicaid waivers enable states to cap enrollment as a way to curtail program spending. To date, enrollment caps have been used primarily for waiver expansion populations (e.g., in the Utah and Iowa waivers), but caps on the current enrollees in optional eligibility categories have also been approved in at least two states (Massachusetts and Oregon). Under HIFA, several states (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Maine, and Oregon) received waivers to cap the number of newly covered enrollees, and many have used the cap. Oregon, for example, used its new enrollment cap to reduce the number of expansion enrollees in the program, from 104,000 in January 2003 to about 24,000 by the end of 2004 (Oberlander 2007).

Clearly, giving states the flexibility to expand coverage to new populations helps those who might otherwise be uninsured. Expanding coverage also has positive spillover effects on the health care safety net; that is, by having more people insured, the safety net's burden diminishes. States' coverage activity has been mixed on this dimension. A few states (e.g., Illinois and New York) have undertaken significant Medicaid expansions but the vast majority have only undertaken modest expansions or reduced coverage.

The consequences for those who lose Medicaid coverage are very real. Except perhaps for some higher-income beneficiaries who might have other insurance options, many Medicaid beneficiaries generally do not (Kenney and Cook 2007; Long and Graves 2006). Thus they would likely join the ranks of the uninsured. Studies evaluating the cost-sharing changes introduced under Oregon's HIFA waiver, for example, revealed that of those persons who lost coverage following an increase in beneficiary cost sharing, 72 percent became uninsured, and many reported high levels of unmet need (Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research 2005; Wright et al. 2005).

Incorporating Market Principles into Medicaid

Besides those changes that make Medicaid look and feel more like private health insurance (such as introducing premiums and copayments), several states have tried to directly privatize parts of the program. Underlying the states' interest in this approach is a belief that private market forces may do a better job than the government in managing costs and quality. The extent to which states have attempted to privatize Medicaid varies greatly, ranging from shifting more beneficiaries into private health plans to establishing health savings accounts. States typically mix and match the various strategies in their Medicaid reform efforts.

Increasing Reliance on Private Managed Care Plans

In the mid-1980s many states shifted large segments of their Medicaid population, mainly children and families, into managed care plans. Although the states hoped to save money and improve access to care, the research evidence regarding these effects is mixed (Hurley and Zuckerman 2003). In the recent wave of waivers, reliance on private health plans has again surfaced, but this time the focus is on moving disabled Medicaid beneficiaries into managed care. Again, states hope to reduce the program's costs while improving disabled persons' access to care. The disabled accounted for 40 percent of total program spending in 2003, so the savings potential is considerable (Urban Institute 2007).

States that plan to rely more heavily on managed care are Massachusetts, Florida, and Vermont. Florida's 2005 waiver, for example, calls for moving nearly all its Medicaid beneficiaries to capitated managed care. Even though Florida has long had a managed care program, nearly two-thirds of its Medicaid population was served through either the traditional fee-for-service system or a primary care case management program before the waiver was implemented. Florida hopes that by moving more of its enrollees into managed care, it will make its program costs grow more slowly (Agency for Health Care Administration 2005).

Furthermore, Florida pays the plans individually adjusted premiums and expects that a variety of health plans will, as discussed earlier, hold substantial leeway in tailoring benefits. The hope is that competition among plans for Medicaid enrollees will save money. In addition, Florida policymakers hope that beneficiaries who are offered a choice of health plans and type of coverage will become better informed and more judicious consumers of health care, which in the long run should cut costs. This notion of consumer choice and program savings is a basic tenet underlying many of the Medicaid privatization strategies.

In an interesting wrinkle, recent waivers in California and New York included explicit federal incentives to shift more of their Medicaid beneficiaries into managed care. Under New York's 2006 1115 waiver, the Federal-State Health Reform Partnership or F-SHRP, the federal government will provide up to $1.5 billion over the five-year demonstration to help the state restructure its health care delivery system, with a particular focus on developing electronic medical records and expanding primary care services. The availability of these funds, however, is subject to New York producing particular program savings. One of the two areas of savings that the CMS will recognize is that the state is expanding its Medicaid managed care program. Similarly, California's 2005 waiver made the release of $360 million in federal funds conditional on the state's achieving certain programmatic milestones in shifting its elderly and disabled beneficiaries into managed care.

Promoting Public-Private Partnerships

Some states have recently promoted Medicaid privatization through public-private partnerships. Although these efforts come in various forms, states typically have looked to the employer-based insurance market to create these partnerships.

Premium Assistance

One of the main ways that states have pursued public-private partnerships has been through premium assistance programs, in which states subsidize individuals' employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) premiums. In recent waivers, premium assistance programs typically have been offered to beneficiaries as an alternative to direct Medicaid coverage. A principal reason why states are interested in these programs is the ability to use private dollars to help finance health insurance for low-income workers who are unable to afford the employees' share of the premium and who would otherwise likely be uninsured. Premium assistance is also viewed as a way to help insured low-income workers maintain their health coverage, a growing need in the current health insurance market, in which premiums have risen significantly faster than wages and employers have been shifting the increases in health care costs to their employees (Gabel et al. 2005).

Although premium assistance has been available for the past several years under Medicaid and SCHIP, it has had fairly limited success, in part because of the federal regulations governing the programs. SCHIP, for example, has rules governing the share of the premium that must be paid by the employer. In addition, benefits provided under the employer plan must be comparable to what is provided under SCHIP. There is also a requirement that enrollment in premium assistance be cost effective compared with direct coverage under SCHIP. These and other rules have complicated the administration of premium assistance programs (Lutzky and Hill 2002). Similar types of rules and regulations apply to Medicaid premium assistance programs.

To promote this strategy, the HIFA waiver authority required a premium assistance component but granted states considerable latitude in its design. For example, HIFA relaxed the cost-effectiveness test and the cost-sharing standards. It also eliminated the requirement that enrollees receiving coverage through premium assistance must have access to the full range of services covered under Medicaid or SCHIP.5

While a premium assistance component is required, the extent to which HIFA states have relied on it in their demonstrations has varied greatly. At one end of the spectrum, Arizona, California, and Colorado were reluctant to implement a program, whereas Idaho, Illinois, New Mexico, and Oregon made premium assistance a centerpiece of their HIFA demonstrations. States' design of premium assistance programs also varies widely along several dimensions, such as the populations that are allowed or required to enroll, the presence or absence of a requirement that an individual has to be uninsured at the time of enrollment, the scope and breadth of the benefit package, the extent of cost sharing, and the level of subsidy provided.

Although there has been substantial activity surrounding premium assistance programs—one recent count reported that at least fifteen states had such a program operating under Medicaid or SCHIP—enrollment to date has been limited (Shirk and Ryan 2006). With about 33,000 enrollees, Massachusetts's premium assistance program is the nation's largest, whereas the enrollment in most state programs is below 5,000.

Medicaid-Only Public-Private Insurance

In an extension of premium assistance, two states, New Mexico and Arkansas, have developed wholly new insurance products through their waiver programs, which rely on a public-private partnership. As part of its HIFA waiver, New Mexico designed a special managed care product that businesses can offer to their low-income workers. Likewise, Arkansas's 2006 HIFA waiver allows the state to offer a specially designed limited benefit package to be sold by one or more private insurance companies and marketed to employers that have not offered group insurance coverage in the past twelve months.

Other Private-Public Partnerships

A leading goal of Massachusetts's 2006 1115 waiver is achieving universal coverage. To reach this goal, the state is relying to a very large extent on public-private partnerships, as well as concessions made by all major health care stakeholders: providers, the state, employers, and individuals. Although Massachusetts is using many strategies to reach its goal, an important one is the Safety Net Care Pool, whose formation was approved as part of the state's 2005 1115 waiver. Among other things, expenditures from the safety net pool can be used to help purchase health insurance for low-wage workers who otherwise would be uninsured.

Health Savings Accounts

Taking privatization further, the DRA included provisions that allow the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to authorize up to ten demonstration programs that would test the combined use of a health opportunity account (HOA) and a high deductible plan for individual Medicaid beneficiaries. The Medicaid programs can deposit into the HOA up to $2,500 per adult and $1,000 per child, which the beneficiary can use to pay both health plan deductibles and other health care costs, as determined by the state. These demonstrations are not required to operate on a statewide basis but are limited to low-income children and parents. They can become part of a state's Medicaid program through the submission of a state plan amendment. As of this writing, only South Carolina had moved forward with an HOA demonstration. In addition, Indiana's Section 1115 waiver (Healthy Indiana Plan) will incorporate a high-deductible health plan with a health savings account for expansion populations, with enrollees' contributions capped at no more than 5 percent of gross family income.

Impacts of Privatization Efforts on Medicaid

While there has been considerable activity in trying to privatize Medicaid, most of the initiatives are small, with the important exception of managed care. Moreover, little is known about their impacts on beneficiaries and the program. Although market-oriented approaches are largely untested, there are several reasons to find them attractive. Perhaps the most compelling is the potential for program cost savings. To the extent that incorporating private market principles into Medicaid makes the program more efficient and reins in spending, these approaches have obvious appeal to both the federal government and the states.

Another attractive feature of privatization strategies is that they offer beneficiaries choices that can also generate program savings. Assuming that full cost and quality information is available, having a choice may make enrollees smarter consumers of health care services, eliminate unnecessary care, and, in return, reduce program costs.

Offering a choice may also improve beneficiaries' satisfaction with care, since they would have to make more decisions about how they use health care services. Another potentially positive spillover effect is that relying more on the private market may help remove some of the stigma sometimes associated with Medicaid, which could encourage more eligible individuals to enroll. Finally, mainstreaming enrollees in the private health market may improve their access to care.

While privatization holds much appeal, several drawbacks may be associated with the approach. A major driving force behind these initiatives is the desire to save money or, at a minimum, to control Medicaid costs. Recent research, however, indicates that in the early 2000s, Medicaid was not more expensive than private insurance (Hadley and Holahan 2003; Holahan and Ghosh 2005). Thus, reducing program costs may be difficult. Another important consideration when moving to a market model is that administrative costs will likely be high for both the state and the health plans. A shift to a market-oriented Medicaid program would certainly drive up administrative costs, as the states would need to manage a wide range of health plans, each providing a different set of services, or to monitor personal health accounts or to track enrollees in premium assistance. Besides administrative costs, private health plans typically pay providers more than Medicaid does, which could limit the plans' ability to deliver lower-cost, quality care.

The success of privatizing Medicaid also hinges largely on the ability to accurately adjust premiums for risk. While Maryland has successfully used risk-adjusted capitation payments in its Medicaid managed care program (Chang et al. 2003) and many states have adopted risk-adjusted payments as part of their Medicaid managed care programs (Kronick 2005), risk adjustment methods are still being refined and may not be sufficiently advanced to support a fully privatized Medicaid program in all jurisdictions. If payments cannot be adequately adjusted, privatization could potentially lead to having healthier enrollees in one set of plans and those with chronic disabilities in another. Over the long term, it may not make business sense for a plan to offer coverage that meets the needs of patients with higher expected costs (Lee and Tollen 2002). Risk adjustment may be particularly challenging for the Medicaid population because of the inclusion of disabled enrollees, who may have special and great health care needs. If payments were not reliably and accurately set, the potential for financial losses for plans would be great, which would make it difficult to secure and keep participants in the health plans.

Finally, a basic tenet underlying market-based approaches is the assumption that individuals would make informed health care choices. However, all the information needed (such as consistent provider quality-of-care data and accurate health plan performance measures) to ensure sound decision making is not now available (Lee and Tollen 2002). Accordingly, poorly informed enrollees may buy less or lower-quality care but pay more for it. Furthermore, making informed health care choices presumes that individuals can successfully navigate a complex health care system and make complicated decisions about how to best use health care services. Research indicates that these are problems for the general population, as nearly half of all American adults have difficulty understanding and using health information (IOM 2004). Making wise health care decisions may pose a particular problem for the Medicaid population, as research indicates that advanced age, limited formal education, and poor health status—characteristics common among program beneficiaries—are predictors of poorer comprehension skills (Hibbard et al. 2001).

Revamping Medicaid Financing and Supplemental Payments

Aimed at improving the program's fiscal integrity, several of the more recent waivers have focused on restructuring state Medicaid financing and supplemental provider payment policies, particularly hospital reimbursement. Waivers that fall into this category were granted to California, Iowa, Florida, and Massachusetts.

Beginning in the late 1980s, many states started to use various financing and payment arrangements that enabled them to receive increased federal Medicaid revenues with a limited or no contribution from the state (Coughlin and Zuckerman 2003; U.S. GAO 1994, 2000, 2005; U.S. HHS 2001a, 2001b). To accomplish this, states used a variety of revenue and payment strategies, including taxes on health care providers, intergovernmental transfers (IGTs), and disproportionate share hospital (DSH) and upper payment limit (UPL) payments. Readers are referred elsewhere for a full treatment of these financing and payment arrangements (see, e.g., Coughlin and Zuckerman 2003), but in brief, these strategies created the illusion that a state had made a contribution, thereby allowing it to collect its federal Medicaid match.

The net effect of these strategies was that the federal government paid more for Medicaid than it was supposed to under the matching formula, whereas the states paid less. Furthermore, there was no assurance that the federal dollars paid through these mechanisms were used to finance health care for Medicaid beneficiaries. Indeed, several studies suggest that in some instances, states used the federal dollars they gained through special financing mechanisms for nonhealth purposes (Coughlin, Bruen, and King 2004; Ku 2000).

The Bush administration has attempted to control such financing and payment mechanisms. Some recently approved 1115 waivers include conditions requiring states to phase out their use of Medicaid special financing strategies.6 Some waivers maintain the level of federal funds that had been generated through special financing and payment arrangements but require states to abide by certain conditions to retain them. Iowa's 2005 1115 waiver, for instance, requires that the state terminate several financing practices, as well as not impose any new provider taxes to finance its share of Medicaid spending for the duration of the demonstration period. In exchange for meeting these and other conditions, Iowa can continue to receive federal dollars through its special financing and payment arrangements but is now required to use the funds to provide services to low-income, uninsured individuals, among other things. Although the details differ, California's, Florida's, and Massachusetts's waivers entail similar provisions that allow them to continue receiving federal funds obtained through special financing and payment practices.

Another common feature is reducing or eliminating state use of IGTs for the states' shares of Medicaid expenditures. Virtually all the waivers include such a condition. California, for example, agreed to limit (but not completely eliminate) its use of IGTs for funding the state's share of DSH payments. Likewise, Florida's waiver calls for the state to terminate its use of IGT financing, which had funded $1 billion in hospital UPL payments in 2005. The Massachusetts and Iowa waivers also require that these states eliminate the use of IGT funding of hospital payments, as well as other supplemental payments such as medical education, nursing home, and managed care. In lieu of IGTs, some of the states are allowed to use certified public expenditures, or CPEs, for their share of Medicaid expenditures. CPEs are expenditures for Medicaid-covered services paid for and provided by a public entity, for example, a university teaching hospital or a county public hospital.

These waivers related to special financing and payment arrangements also call for the use of safety net pools that states can draw on to support health care for the uninsured. Again, the specifics vary, but the pools have enabled California, Florida, and Massachusetts to finance health care expenditures provided to uninsured individuals in a variety of settings from clinics to hospitals. In addition to paying for health care services, pool funds can also be used to purchase insurance. Allowing states to develop these pools and to finance a broad array of health-related activities and providers is a significant departure from traditional Medicaid policy, which in the past has limited spending on the uninsured largely to care provided in hospitals.

The financing and payment-related provisions included in the recent waivers have broad implications for the program, both positive and negative. On the positive side, by more directly spelling out program financing rules, these waivers set out to restore fiscal integrity to Medicaid. Special financing and payment programs have generated considerable controversy between the states and the federal government. These new policies could ease that tension, which may help advance the Medicaid policy debate beyond financing matters, which have dominated discussions in recent years.

Another potentially positive attribute of these financing and payment changes is that they allow states to expand the ways in which they provide care to the uninsured. As mentioned, to date the principal vehicle by which Medicaid has financed care for the uninsured has been through DSH payments. Enabling states to divert some of these and other funds to pay for services rendered by other providers or to pay for health insurance could have wide-ranging effects on how care is provided to the nation's uninsured.

A potential downside to the new financing and payment initiatives is that eliminating the use of IGT or provider taxes may reduce some states' ability to finance their Medicaid programs. Over time, many states have relied on these tools, and as such, they have become an integral part of the states' Medicaid financing. A change in the policies governing these strategies could leave many states with significant holes in their Medicaid budgets.

Another potential problem is that a shift in how DSH dollars are spent could have important consequences for safety net providers, in particular hospitals. With more than $18 billion (federal and state) in DSH payments made in 2006 (Urban Institute 2008), a loss of even a portion of those dollars could have considerable financial implications for safety-net hospitals, many of which operate with relatively narrow margins (IOM 2000). The closure or downsizing of safety-net hospitals could affect access to care for Medicaid beneficiaries, given their heavy reliance on these facilities for services.

Conclusion

Broad Medicaid reform continues to elude federal policymakers, but since 2001 many states have been allowed to adopt smaller, incremental changes to the program through waivers and provisions in the DRA. Many of these changes have been actively encouraged by the Bush administration and reflect the administration's strong belief in federalism, fiscal prudence, state flexibility, and the introduction of private market features. The administration, for example, exhibited its commitment to fiscal prudence in the waiver process by negotiating changes in some states' special financing practices. Similarly, it has promoted program flexibility by giving states new discretion related to eligibility, benefits, cost sharing, and the delivery of care, among other things.

While there has been substantial activity, the changes that most states have implemented have been fairly circumscribed. For example, for the most part states have not taken full advantage of the benefit or cost-sharing flexibility that has been made available. Likewise, the use of enrollment caps has been limited. States also have not made full use of privatization strategies, such as managed care for the disabled or premium assistance programs.

This limited response may be attributed to the generally sound fiscal situation that most states have enjoyed in the last few years, but that could now be changing. It could also be attributed to policymakers recognizing that some of the new flexibility may not buy them much. Benefit flexibility, for instance, will not produce great savings if the newly restricted services have so far been used only rarely. To generate substantial program savings, expensive services such as inpatient hospital care would need to be reduced. State policymakers may understand that this strategy might not be prudent because most Medicaid beneficiaries do not have alternative insurance options and thus the state would likely end up paying for their health care—but without the benefit of the federal share. A similar scenario applies to cost sharing: Medicaid beneficiaries are, by definition, poor, and imposing cost sharing could prove harmful to their health if they forgo or delay needed health care, a problem that is particularly relevant to people with chronic conditions. Moreover, in all likelihood, the patients would eventually seek the needed care, but it would likely cost more to treat them.

There are, however, important exceptions to states' relatively tepid response to the new Medicaid flexibility. Oregon, for example, used virtually all the flexibility provided under its HIFA waiver. It raised cost sharing, reduced benefits, and capped enrollment, and the results have been dramatic: within a few months, tens of thousands of beneficiaries disenrolled, and the state's uninsurance rate climbed to 17 percent—the highest rate seen in more than a decade (Oberlander 2007). Similarly, Tennessee has rolled back its long-standing commitment to covering all its low-income residents. Florida is shifting almost its entire Medicaid population to managed care and is changing its benefit package so beneficiaries are no longer guaranteed a particular set of benefits. And a few states, including Florida, Massachusetts, and California, are making significant changes in both how they finance their share of Medicaid expenditures and how they pay safety-net hospitals.

Although on the whole states did not jump on the flexibility and privatization bandwagon, as some expected, much of the policy groundwork to make substantial changes in short order has been laid. What this portends for the future of the program is not clear. As the economy takes a downturn, states may more aggressively exercise the new flexibility.

At present, we know very little about the impacts of the changes that have already been implemented. For example, do program beneficiaries make informed choices about their health care? Are beneficiaries more satisfied because they have more choices or because they have a greater financial stake in the costs of care? How do beneficiaries, especially the disabled, fare under the defined benefit approach that is being tested in Florida's waiver? With the changes in financing rules, how do states cope with rising Medicaid spending and competing budget demands? Have safety-net providers been adversely affected by the potential loss of Medicaid revenues? Answering these and other questions will be critical to understanding how increased flexibility, privatization efforts, and revamped Medicaid financing affect all major Medicaid stakeholders: beneficiaries, providers, states, and the federal government.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through the Urban Institute's Assessing the New Federalism Project. The authors thank John Holahan for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and Bodgan Tereshchenko for his research assistance. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Urban Institute, or its trustees or funders.

Endnotes

Section 1115 waivers, named after a section in the Social Security Act, are the broadest of the federal waiver authorities. There are some narrowly defined section 1115 waivers, however, that focus on specific services such as family planning or that have dealt with special circumstances, such as the disruptions associated with Hurricane Katrina. Other important waiver authorities are section 1915(b) and section 1915(c).

The DRA contains several other Medicaid provisions, including imposing new citizenship documentation requirements, tightening targeted care case management programs, changing prescription drug payment policies, and limiting the circumstances under which individuals can transfer financial assets to qualify for Medicaid nursing-home care. Some of the act's provisions call for increased spending on Medicaid, including providing health care relief related to Hurricane Katrina and establishing a demonstration, “Money Follows the Person,” in which enhanced federal funding may be given to states that shift elderly or disabled individuals out of institutions and into the community. But in keeping with the theme of this article, we limit our discussion to the DRA's provisions pertaining to increasing Medicaid flexibility.

Under federal Medicaid law, a state is required to have an approved Medicaid plan, which, among other things, sets out program eligibility standards, benefits, and reimbursement before federal Medicaid matching funds can be paid. If a state wishes to make a change in its program, it must request an amendment to its Medicaid plan and obtain approval from the CMS. If there is a change in federal Medicaid law, the states also must amend their plans to conform to the revised statute.

In response to a lawsuit brought by the Oregon Law Center against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Oregon Department of Human Services, in June 2004 the state eliminated copayments (but not premiums) for many optional and expansion enrollees. Among other things, the lawsuit charged that that the copayment and premium requirements for enrollees under the HIFA waiver were too high and, as a result, posed an access barrier. The U.S. District Court for Oregon ruled that the Medicaid statute allowed nominal cost sharing for categorical populations but not for noncategorical populations and ordered the state to eliminate all copayments for noncategorical enrollees. The court did not eliminate premiums, however, because it did not consider them to be cost sharing. Interestingly, categorical enrollees are still required to pay nominal copays.

In brief, a cost-effectiveness test requires the states to demonstrate that it is less costly to provide coverage through a private health plan than through direct Medicaid or SCHIP coverage.

Besides waivers, the federal government has also tried to eliminate these financing arrangements through the state plan amendment process (Schwartz et al. 2006). In 2003, for example, the CMS began asking states to respond to “Five Funding Questions” before approving plan amendments. As of August 2006, at least twenty-five were reported as having changed Medicaid funding practices in response to CMS's stepped-up review.

References

- Agency for Health Care Administration. Florida Medicaid Reform: Approved 1115 Research and Demonstration Waiver Application, August. 2005. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://ahca.myflorida.com/Medicaid/medicaid_reform/waiver/index.shtml.

- Artiga A, O'Malley M. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2005. Increasing Premiums and Cost Sharing in Medicaid and SCHIP: Recent State Experiences. May. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) National Health Expenditure Data. 2006. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/25_NHE_Fact_Sheet.asp#TopOfPage.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) Related Medicaid State Plan Amendments. 2008a. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DeficitReductionAct/03_SPA.asp#TopOfPage.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicaid Waivers and Demonstrations List. 2008b. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicaidStWaivProgDemoPGI/MWDL/list.asp.

- Chang DI, Burton A, O'Brien J, Hurley RE. Honesty as Good Policy: Evaluating Maryland's Medicaid Managed Care Program. The Milbank Quarterly. 2003;81(3):389–414. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin TA, Bruen B, King J. State Use of Medicaid UPL and DSH Financing Mechanisms. Health Affairs. 2004;23(2):245–57. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin TA, Long SK, Graves J, Yemane A. An Early Look at Ten State HIFA Waivers. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):w204–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin TA, Zuckerman S. States' Use of Medicaid Maximization Strategies to Tap Federal Revenues: Program Implications and Consequences. In: Holahan J, Weil A, Weiner JM, editors. Federalism and Health Policy. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 145–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis ER, Roberts D, Rousseau DM, Schwartz K. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2007. Medicaid Enrollment in 50 States. October. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel J, Claxton G, Gil I, Pickreign J, Whitmore H, Finder B, Hawkins S, Rowland D. Health Benefits in 2005: Premium Increases Slow Down, Coverage Continues to Erode. Health Affairs. 2005;24(5):1273–80. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley H, Reschovsky J, Cunningham P, Dubay L, Kenney G. Washington, D.C.: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2005. Insurance Premiums and Insurance Coverage of Near-Poor Children. October. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley J, Holahan J. Is Health Care Spending Higher under Medicaid or Private Insurance? Inquiry. 2003;40(4):323–42. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML, Tusler M. Is the Informed Choice Policy Approach Appropriate for Medicare Beneficiaries? Health Affairs. 2001;20(3):199–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan J. Variation in Health Insurance Coverage and Medical Expenditures: How Much Is Too Much? In: Holahan J, Weil A, Weiner JM, editors. Federalism and Health Policy. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 111–44. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan J, Ghosh A. Understanding the Recent Growth in Medicaid Spending. Health Affairs Web Exclusive. 2005:w5-52–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RE, Zuckerman S. Medicaid Managed Care: State Flexibility in Action. In: Holahan J, Weil A, Weiner JM, editors. Federalism and Health Policy. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 215–48. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) America's Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, D.C.: 2004. [accessed April 3, 2008]. report brief, April. Available at http://www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/19/726/health%20literacy%20final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney G, Cook A. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute's Health Policy Online; 2007. Coverage Patterns among SCHIP-Eligible Children and Their Parents. no. 15, February. [Google Scholar]

- Kronick R. Hamilton, N.J.: Center for Health Care Strategies; 2005. Health-Based Payment: Full-Employment for Actuaries or Support for Chronic Care? PowerPoint Presentation. March. [Google Scholar]

- Ku L. Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2000. Limiting Abuses of Medicaid Financing: HCFA's Plan to Regulate the Medicaid Upper Payment Limit. September. [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Coughlin TA. Sliding Scale Premium Health Insurance Programs: Four States' Experiences. Inquiry. 1999;36(4):471–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Tollen L. How Low Can You Go? The Impact of Reduced Benefits and Increased Cost Sharing. Health Affairs Web Exclusive. 2002:w229–41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr K, Brook RH, Kamberg CJ, Goldberg GA, Leibowitz A, Keesey J, Reboussin D, Newhouse JP. Use of Medical Care in the RAND Health Insurance Experiment: Diagnosis- and Service-Specific Analyses in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Medical Care. 1986;24(suppl.):S1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Graves JA. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2006. What Happens When Public Coverage Is No Longer Available? policy brief, January. [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Graves JA, Zuckerman S. Assessing the Value of the NHIS for Studying State Health Care Reform: The Case of New York. Health Services Research. 2007;42(6):2332–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzky A, Hill I. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute; 2002. Premium Assistance Programs under SCHIP: Not for the Faint of Heart. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Medicaid Policy Institute (MMPI) The MassHealth Waiver Issue Brief. 2005. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Boston, April. Available at http://masshealthpolicyforum.brandeis.edu/publications/pdfs/26-Apr05/IssueBrief26.pdf.

- National Governors' Association (NGA) Medicaid Reform: A Preliminary Report. Washington, D.C.: 2005. June. [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse JP. Consumer-Directed Health Plans and the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Health Affairs. 2004;21(3):207–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.6.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander J. Health Reform Interrupted: The Unraveling of the Oregon Health Plan. Health Affairs Web Exclusive. 2007;26(1):w96–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research. HRSA State Planning Grant: Addendum to the Final Report to the Secretary. 2005. [accessed April 3, 2008]. September. Available at http://www.oregon.gov/OHPPR/RSCH/docs/HRSAReport2005final.pdf.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. State Coverage Initiatives, “Profiles in Coverage: Oklahoma Employer/Employee Partnership for Insurance Coverage (O-EPIC) Program. 2008. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://statecoverage.net/oklahomaprofile.htm.

- Rosenbaum S, Markus A. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2006. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005: An Overview of Key Medicaid Provisions and Their Implications for Early Childhood Development Services. October. [Google Scholar]

- Rudowitz R, Schneider A. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2006. The Nuts and Bolts of Making Medicaid Policy Changes: An Overview and a Look at the Deficit Reduction Act. August. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Gehshan S, Weil A, Lam A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy for State Health Policy; 2006. Moving beyond the Tug of War: Improving Medicaid Fiscal Integrity. August. [Google Scholar]

- Shenkman EA, Vogel B, Boyett JM, Naff R. Disenrollment and Re-Enrollment Patterns in a SCHIP. Health Care Financing Review. 2002;23(3):47–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk C, Ryan J. Washington, D.C.: National Health Policy Forum, George Washington University; 2006. Premium Assistance in Medicaid and SCHIP: Ace in the Hole or House of Cards? National Health Policy Forum Issue brief no. 812. July. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumerai SB. Benefits and Risks of Increasing Restrictions on Access to Costly Drugs in Medicaid. Health Affairs. 2004;23(1):135–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumerai SB, Avorn J, Ross-Degnan D, Gortmaker S. Payment Restrictions for Prescription Drugs under Medicaid: Effects on Therapy, Cost, and Equity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;317(9):550–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708273170906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Ross-Degnan D, Casteris CS, Bollini P. Effects of Limiting Medicaid Drug-Reimbursement Benefits on the Use of Psychotropic Agents and Acute Mental Health Services by Patients with Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(10):650–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Avorn J, McLaughlin TJ, Choodnovskiy I. Effects of Medicaid Drug-Payment Limits on Admission to Hospitals and Nursing Homes. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325(15):1072–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110103251505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, Abrahamowicz M, Scott S, Mayo N, Hurley J, Grad R, Latimer E, Perreault R, McLeod P, Huang A, Larochelle P, Mallet L. Adverse Events Associated with Prescription Drug Cost-Sharing among Poor and Elderly Persons. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(4):421–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FJ, Burke C. Executive Federalism and Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: Implications for Policy and Democratic Process. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2007;32(6):971–1004. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban Institute. 2007. Urban Institute Estimates Based on CMS 64 Data from 2001 and 2004.

- Urban Institute. 2008. Urban Institute Estimates Based on CMS 64 Data from 2006.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (U.S. HHS) Review of Illinois' Use of Intergovernmental Transfers to Finance Enhanced Medicaid Payments to Cook County for Hospital Services. 2001a. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/50000056.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (U.S. HHS) Review of Medicaid Enhanced Payments to Public Providers and the Use of Intergovernmental Transfers by the Alabama State Medicaid Agency. 2001b. [accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at http://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region4/40002165.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office (U.S. GAO) State Use of Illusory Approaches to Shift Program Costs to Federal Government. Washington, D.C.: 1994. GAO/HEHS-94-133. August. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office (U.S. GAO) Medicaid: State Financing Schemes Again Drive up Federal Payments. Washington, D.C.: 2000. GAO/T-HEHS-00-193. September. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office (U.S. GAO) Medicaid: States' Efforts to Maximize Federal Reimbursements Highlight Need for Improved Federal Oversight. Washington, D.C.: 2005. GAO-05-836T. June. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BJ, Carlson MJ, Edlund T, DeVoe J, Gallia C, Smith J. The Impact of Increased Cost Sharing. Health Affairs. 2005;24(4):1106–16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]