Abstract

The life expectancy of African Americans has been substantially lower than that of white Americans for as long as records are available. The life expectancy of all Americans has been lower than that of all Canadians since the beginning of the 20th century. Until the 1970s this disparity was the result of the low life expectancy of African Americans. Since then, the life expectancy of white Americans has not improved as much as that of all Canadians. This article discusses two issues: racial disparities in the United States, and the difference in life expectancy between all Canadians and white Americans. Each country's political culture and institutions have shaped these differences, especially national health insurance in Canada and its absence in the United States. The American welfare state has contributed to and explains these differences.

Keywords: Disparities, insurance, Canada, mortality, African Americans

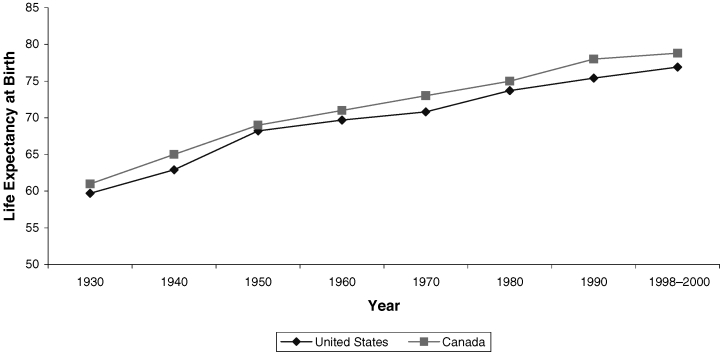

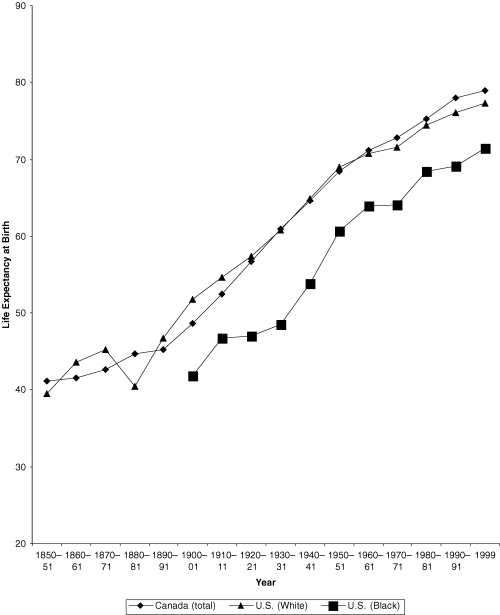

It has been widely recognized that both in the past and at present, white and African-American citizens have had very different mortality experiences. Perhaps somewhat less well known is the fact that the populations of the United States and Canada have also had, and continue to have, very different mortality rates. Figure 1 indicates that for most of the 20th century Canada had a small but significant advantage with regard to life expectancy. Figure 2 provides more detail and shows that white American life expectancy was the same as, or better than, that of all Canadians for most of the period from 1850 to 1950 (Haines and Steckel 2000, 696–7). Only in the 1970s did the Canadian figure rise above that of white Americans. For the entire 20th century, however, the life expectancy of African Americans was substantially below that of both white Americans and Canadians, which accounts for most of the Canadian advantage until 1970. After that time, the life expectancy of both white and black Americans has been lower than that of Canadians.

Figure 1.

Life Expectancy at Birth, Total U.S. and Canadian Populations, 1930–2000

Figure 2.

Life Expectancy in Canada and the United States, 1850–2000

These observations raise the two issues addressed in this article. One pertains to the continuing importance of race in America. The other concerns what happened in the 1970s to make the life expectancy of even white Americans drop below that of all Canadians. The first part of this article compares the mortality of whites and African Americans and argues that the impact of slavery on American political institutions helped shape the American welfare state. I do not consider the many ways in which racism has shaped the mortality experience of African Americans, such as psychosocial stress, domestic relationships, and substance abuse. Rather, my focus is on how the effect of racism on mortality was determined by American political institutions. The second part of the article deals with the difference between all Canadians and white Americans, especially how political culture and institutions have affected the differences between the mortality experiences of the two countries.

This article also makes two arguments. The first is that the policies forming the American welfare state contributed substantially to the differences in the health of whites and African Americans as well as to the differences between the health of white Americans and all Canadians. The second argument is that social policies have deep historical roots in political institutions and culture, sometimes making them difficult to change.

To examine these differences within and between the two countries, in addition to the life expectancies at birth shown in Figures 1 and 2, I use the differences in age-specific rates of death due to causes that the European Consensus Conference on Avoidable Mortality agreed were amenable to interventions by health care systems. The definition of a properly functioning health care system is broad:

Medical care is defined in its broadest sense, that is prevention, cure and care, including the application of all relevant medical knowledge, the services of all medical and allied personnel, the resources of governmental, voluntary, and social agencies, and the cooperation of the individual himself. An excessive number of such unnecessary events serves as a warning signal of possible shortcomings in the health care system, and should be investigated further.

(Holland 1991, 1, italics added)

I emphasize “warning signal” because I do not claim that all the disparities I describe can be attributed only to unequal access to, and utilization of, health services, even broadly understood. But the disparities in causes of death widely regarded as amenable to intervention by the health care system, that is, “avoidable causes,” should not be dismissed with the therapeutically nihilistic assertion that health care makes no difference at the population level. Table 1 lists some of these avoidable causes.

TABLE 1.

Some Avoidable Causes of Mortality

| Cause | ICDA 9th Revision | Age Group | Responsible Health Care Sector | Other Potential Factors Contributing to Excess Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal mortality | 630–676 | All ages | Primary care, hospital | |

| Perinatal | All causes | <1 week & still- births, >28 wk. gestation | Primary care, hospital | Prevalence of premature births |

| Chronic rheumatic heart disease | 393–398 | 5–44 | Primary care, hospital | |

| All respiratory diseases | 460–519 | 1–14 | Primary care, hospital | |

| Hodgkin's disease | 201 | 15–64 | Primary care, hospital | |

| Cervical cancer | 180 | 15–64 | Public health, primary care, hospital | Sexual habits, coding error |

| Breast cancer | 174 | 25–64 | Screening programs, public health, primary care, hospital | Risk factors affecting incidence: obesity, family history |

| Tuberculosis | 010–018, 137 | 5–64 | Public health, primary care | Ethnic group (immigration); nonhospital compliance with treatment |

| Asthma | 493 | 5–44 | Primary care | Prevalence of disease |

| Appendicitis, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, abdominal hernia | 540–543 574–575.1 550–553, 576.1 | 5–64 | Primary care, hospital | Coding error |

| Ischemic heart disease | 410–414, 429.2 | 35–64 | Public health, primary care, hospital | Coding error, health, behavior affecting incidence: smoking, weight, nutrition |

| Hypertension & cerebrovascular disease | 401–405, 430–438 | 35–64 | Public health, primary care, hospital | Coding error, health behavior affecting incidence: smoking, weight, nutrition |

| Peptic ulcers | 531–534 | 25–64 | Primary care, hospital | Drug use, alcohol, smoking |

| Diabetes | 250 | All ages | Public health, primary care, hospital | Diet, obesity |

| HIV/AIDS | 042–044 | All ages | Public health, primary care, hospital | Drug use, sexual behavior |

Sources: Adapted from Manuel, D.G., and Y. Mao. 2002. Avoidable Mortality in the United States and Canada, 1980–1996. American Journal of Public Health 92:1481–4; and EC Working Group on Health Services and W.W. Holland, ed. 1997. Avoidable Deaths. European Community Atlas of “Avoidable Death” 1985–89. Oxford: Oxford University Press. HIV/AIDS and diabetes do not appear in either publication.

Race and Welfare in the United States

Although the Civil War determined that the United States would remain united, it did not result in equality between African Americans and other Americans. Although slavery was abolished, it was replaced by debt bondage, poverty, segregation, violence, deprivation of civil and political rights, and lack of educational opportunities and health services (Byrd and Clayton 2000). Usually the only work available to black men in the South was as agricultural laborers and sharecroppers, and to black women, as domestic servants.

The abolitionist passions that had helped fuel the war receded from the North, along with the willingness to support civil rights and land reform (Beckert 2001, 224–32). But the persistent disenfranchisement of African-American citizens meant that southern politics would be dominated by whites, and because the Republican Party was the party of Lincoln, the Democratic Party dominated the South. Long-serving white Democrats thus came to represent the South in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, in which, because of the seniority system, they ultimately controlled the chairmanships of many important committees (Quadagno 1994). Thus, by the time of the Great Depression of the 1930s when the Democratic Party came to power under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, it was comprised of an unwieldy coalition of conservative southern whites jealously guarding the rights of states and the status quo with respect to race relations, and northern representatives of industrial workers and urban political machines. The urban reform movement and what would have been a socialist or social democratic party were submerged within this coalition, and it was this coalition that was largely responsible for the welfare legislation passed during the New Deal.

Among the most important pieces of legislation was the Social Security Act of 1935, which represented both a historic assumption of responsibility for welfare by the federal government and a series of compromises that weakened its universality. The compromises resulted from the need to appease the conservative coalition in Congress of southern Democrats and Republicans. While it is true, as Theodore Marmor observed (2000b), that there were important nonracist motives behind the Social Security Act, an important consideration for southern legislators was the exclusion of African Americans. As many commentators have noted, Old Age Insurance was a federally administered, contributory program that included workers in many industries but excluded agricultural laborers and domestic servants, the two occupations in which African Americans in the South predominated. Aid to Dependent Children was a means-tested, noncontributory program administered by the states, and unemployment insurance was sort of a hybrid of the other two. It, too, excluded domestic servants and agricultural workers from benefits, and it did not provide national standards for receiving unemployment insurance (Lieberman 1998; Quadagno 1994, 21). Thus, Old Age Insurance was a national system with national standards, and over several decades it became increasingly inclusive as African Americans moved into jobs that gave them access to its benefits. Aid to Dependent Children was based on the notion of charity. Because it was believed that poor people differed in terms of their worthiness for charity, the decisions as to who should receive aid were best made locally. In practice, this policy meant that the federal government could not establish national standards, administer the program nationally, and intrude in the affairs of the states.

The Social Security Act was not the only piece of New Deal legislation to discriminate against African Americans. As Jill Quadagno pointed out, most craft unions that were part of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) discriminated against African Americans, and when the National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, was passed in 1935, it did not bar such discrimination by the unions. Indeed, had such a clause been included, the AFL would not have supported the legislation. The Wagner Act gave workers the right to organize and join unions, however, and thus gave a great impetus to unionization among industrial workers, many of whom were African Americans. Large numbers of blacks joined the newly formed Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), for without them unionization would have been impossible. Until the AFL and CIO merged in 1955, “the skilled trade unions maintained policies of racial exclusion and segregation with the tacit approval of the federal government” (Quadagno 1994, 23).

Quadagno also observed that the National Housing Act of 1934, which created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), was meant to guarantee low-cost housing loans for working-class families. The loans were meant to be “sound,” and in practice this meant not providing loans for homes in African-American or mixed neighborhoods and encouraging restrictive covenants prohibiting the sale of homes to African Americans. Housing policy went further, however, for the Housing Act of 1937 allowed local authorities to use tax-free bonds to build public-housing projects, with federal funds being used to subsidize rent for the poor. In practice, such housing projects were built in racially segregated neighborhoods (Quadagno 1994, 23). Thus, home ownership was for whites, and rentals were for African Americans. Working-class neighborhoods remained racially segregated, even when unskilled employment in some industries began to include more African Americans. An important consequence was that a racially inclusive working class was unlikely to emerge under circumstances in which the federal government helped perpetuate distinctions along racial lines. Moreover, intergenerational accumulation of wealth in the form of home ownership was severely limited for African Americans, as compared with whites (Oliver and Shapiro 1995; Shapiro 2004).

One important piece of legislation that was not passed, either during the New Deal or later, was the inclusion of compulsory health insurance in the Social Security Act. This is a story that has often been told and does not require retelling here. But I will make only one observation. During World War II, the implicit Democratic coalition collapsed when the “southern pro-labor voting stopped.” According to Ira Katznelson and his coauthors, this occurred for two reasons. First, the South “had little to offer the war effort at a time when both capital and labor in the North, including black labor, were critically important to military production.” As a result, the bargaining power of the southern political elites was weakened. “Second, wartime labor shortages and military conscription facilitated labor organizing and civil rights agitation” (Katznelson, Geiger, and Kryder 1993, 297).

In addition, the growing importance of African-American voters in the North and the growing pressure from civil rights organizations, especially the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, led President Harry Truman to “embrace a program of civil rights for blacks” (Grantham 1994, 199). As one southern leader wrote in 1948, southerners “know that they have kept the democratic [sic] party alive for the past seventy-five years; that but for them there would have been no Cleveland or Wilson administrations and, perhaps, no Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration.” They thus assumed

that they had the right to expect fair treatment at the hands of the democratic [sic] party. They didn't expect to be maligned and misrepresented by its leaders; nor did they expect that the democratic doctrine of state sovereignty, fundamental principle of our constitutional scheme of government, would be repudiated, or that the party would move to destroy [the] social standards of the South, under which the relations between the white and Negro races of the South have steadily improved.

(Grantham 1994, 200)

Thus in the postwar years, “the national Democratic party could no longer be counted on to represent the South” (Grantham 1994, 200), and the South ceased to support prolabor legislation, as it had in the New Deal congresses. Without southern support, the Democratic Party was unable to become the social democratic vehicle by which the labor movement could achieve “politically guaranteed social benefits” for all (Katznelson, Geiger, and Kryder 1993, 301–2), and in the late 1940s when President Truman attempted to get a plan for national health insurance passed, he was soundly defeated. As a result, the labor movement settled for employment-based programs, and proinsurance reformers began to think in much more modest terms than coverage for the entire population, settling on the elderly recipients of Social Security benefits as the most likely group of beneficiaries (Marmor 2000a, 17).

During the Eisenhower years in the 1950s, there was no chance that the reformers’ bill would be passed. Even during President John F. Kennedy's term of office (1961–63), liberal Democrats did not command enough votes to pass Medicare. Only as a result of President Lyndon B. Johnson's overwhelming victory in the Democratic landslide of 1964 did its passage become possible. In an ingenious legislative stroke, two bills—the reform bill covering Social Security recipients and the conservative bill covering the poor—were combined into Medicare and Medicaid. The first was based on the reformers’ belief in universal entitlement, the second, on their opponents’ belief in individual responsibility, local control, and the need for means testing. But Medicaid was also meant to be what Arkansas representative Wilbur Mills, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, called a fence around Medicare, a way of limiting its spread to other sectors of the population (Marmor 2000a, 53). Indeed, Mills, a southern Democrat, had pursued the same policy as his southern predecessors had, by limiting an entitlement program and giving the states control over benefits for the poor. And he succeeded, for unlike Old Age Insurance, which has become steadily more inclusive, Medicare has not been what its creators had hoped it would be: the first step on the way to universal entitlement.

Segregation and Inequality

What, then, has been the legacy of these policy developments in regard to disparities in the health of African Americans and whites? To answer that question I consider how the context created by the legislation just described helped shape the experience of African Americans. I focus on racial segregation and inequality, for these are perhaps the most immediately obvious manifestations of the discriminatory laws that have formed the foundation of the American welfare state. Several studies have shown that each is associated with an increased risk of death among African Americans (Jackson et al. 2000; LaVeist 1989, 1993; McCord and Freeman 1990; Polednak 1991, 1993, 1997).

Segregation and inequality in the South persisted after the Civil War because of the failure, indeed the unwillingness, of the victors to dismantle the institutions that had been erected after slavery had been abolished that perpetuated the exclusion of African Americans from full participation in society. Stanley Engerman, Stephen Haber, and Kenneth Sokoloff (2000; Engerman and Sokoloff 2002) compared the economies of various countries in the Western Hemisphere and argued that factor endowments—land, climate, indigenous populations—helped determine the subsequent growth of institutions and the degree of inequality in each country. Those countries in which land suitable for plantations and a large indigenous or imported population had made slavery economically advantageous became far more unequal than did those in which small holdings were relatively equally distributed within the population. Elites in highly unequal countries established institutions that reinforced the early inequality and persist into the present. For example, less is spent on education in such countries because the children of the elite are educated in private schools; financial institutions and easy credit are not widely available; and the franchise has not been inclusive. What is the case at the national level—say the differences between Latin America, on the one hand, and the United States and Canada, on the other—also is true, though to a lesser degree, when the American South is compared with other regions of the United States. That is, the institutional legacy of slavery in the American South has been low educational attainment, high income inequality, and, until recently, lack of access to the polls when compared with the North, the Midwest, and the West.

Many observers have commented on the impact of these historic patterns of inequality on health care and health status in the South. In the first decades of the 20th century, for instance, physicians delivered the babies of 79 percent of white women in rural Mississippi but only 8 percent of African-American women (Ewbank 1994). One-third of white women but only 12 percent of African-American women had some prenatal care. Similar patterns were found elsewhere in the rural South (Ewbank 1994, 123). Despite major changes, even by the last decade of the 20th century, income inequality was the greatest, and spending on libraries, schools, hospitals, Medicaid programs (Blendon et al. 1989), and other services was the lowest in the South compared to other regions of the United States (Kaplan et al. 1996). Furthermore, these patterns of inequality have consistently been shown to be associated with higher mortality in the southern states than elsewhere.

Of course, as southerners have been among the first to point out, racial segregation is not a uniquely southern phenomenon. It was, and is, common in northern and midwestern cities (Hart et al. 1998). American cities grew by annexing adjacent territory. This generally was advantageous to those living in the areas to be annexed, because they gained access to city services such as paved roads, sewer lines, and public water supplies. But in the first decades of the 20th century the northeastern states began to amend their constitutions to prohibit annexation without the agreement of people in the areas to be annexed. This was an attempt to prevent foreign-born immigrants and African Americans from following well-to-do emigrants from the cities to the suburbs and was part of a more widespread effort by old-stock white Protestants to protect a way of life they perceived to be threatened (Baltzell 1964; Jackson 1985). Federal housing policy in the 1930s thus reinforced patterns of segregation that were already becoming established.

Although this pattern was not the same everywhere, it was more obvious in older American cities in the Northeast and Midwest. David Rusk (1993) labeled them “inelastic” cities, for they have not been able to expand to embrace their spreading regional populations, leading to several important consequences. One is that racial segregation is greater in these areas than elsewhere as a result of exclusionary practices in the surrounding towns. For instance, such towns often refuse to allow low-cost housing, whereas the inner cities have welcomed such projects as a way to replace decayed housing stock. Mandated minimum lot and house sizes also make it difficult for poor people to acquire homes in these communities. Legal enforcement of fair housing practices is difficult as well, for individuals must bear the costs of lawsuits.

Second, the tax base of inelastic cities is relatively small and shrinks even more as the relatively well-to-do flee to the suburbs. As the tax base shrinks, local services, including schools, health care providers, mass transit, and local shops, decline in number and quality as well. That is, in metropolitan areas characterized by inelastic cities, the possibilities for locally redistributive tax policies are significantly diminished compared with those areas that are integrated under one government, and contributions from the federal and state governments are insufficient to make up the deficiencies. The impact has been especially hard on public education and hospitals that serve the urban poor.

In regard to urban health care, the number of physicians practicing in central cities has declined just as other services have, and inadequate Medicaid reimbursement rates and the great need for health services for poor populations all have conspired to lead to the closure of many urban hospitals. Indeed, the proportion of a hospital's patients and the proportion of the African-American population in the hospital's neighborhood are among the best predictors of hospital closure (Whiteis 1998).

Third, inelastic cities are the very ones in which old industries have declined, putting many people out of work. These were the industries in which workers, including those living in segregated urban neighborhoods, had health insurance. With the loss of those jobs, health benefits were lost as well, more by African Americans than by whites, and with measurable negative consequences (Baker et al. 2002; Blendon et al. 1989; Hadley, Steinberg, and Feder 1991). New employment opportunities requiring literacy and numeracy are not locally available but tend to be located in suburban office parks. Because of the deterioration of urban school systems, many young people do not possess the necessary skills for such jobs, and inadequate mass transit makes them relatively inaccessible anyway (Wilson 1987). Moreover, many of the jobs that are available are in the nonunionized service sector and do not offer health care benefits. All these factors contribute to the disparities between white and African-American life expectancy.

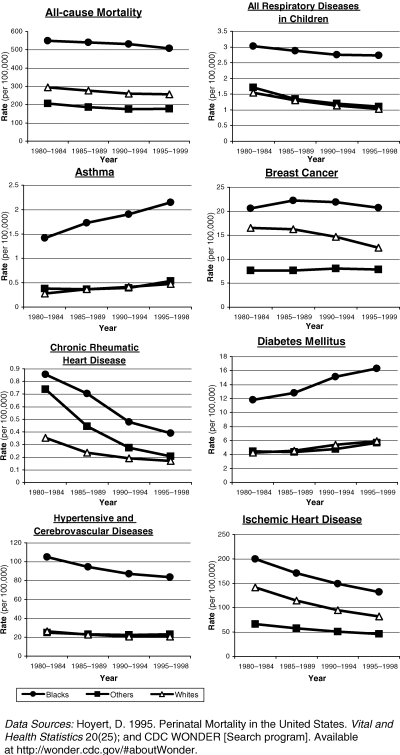

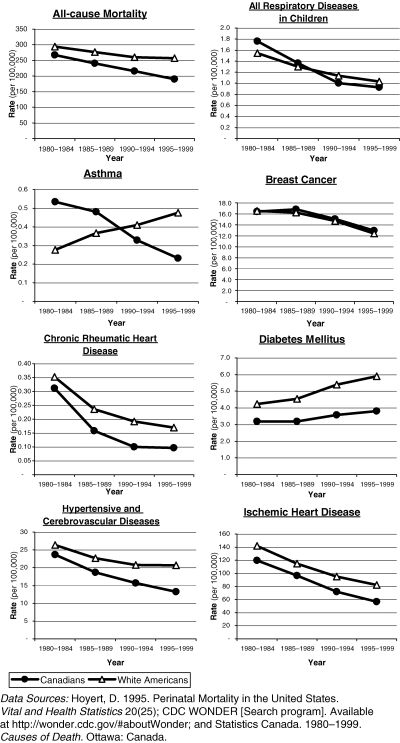

Disparities due to Conditions Amenable to Intervention by the Health Care System

It has been known for some time that proportionately more African Americans than whites die of causes amenable to interventions by the health care system (Carr et al. 1989; Rene et al. 1995; Schwartz et al. 1990; Woolhandler et al. 1985). Figure 3 shows the death rates due to several of these causes from 1980–84 through 1995–98 and 1995–99, in the broad age groups displayed in Table 1 and then adjusted by age within each age group to the 2000 standard U.S. population. Among the causes accounting for the greatest disparity in life expectancy of African Americans and whites are cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases and hypertension (Wong et al. 2002). Although there has been a decline in both causes of death among African Americans, which began in the 1950s but was generally more rapid for whites (Farley and Allen 1987, 42–3), there still is a very large difference in the rates for the two populations. Some of the difference is due to lower rates of vascular surgery among African Americans than among whites (Gittelsohn, Halpern, and Sanchez 1991; Wenneker and Epstein 1989).

Figure 3.

Avoidable Mortality in the United States by Race, 1980–1998/991

The two populations show similarly large differences in the other causes of death amenable to interventions by the health care system. A few have had very dramatic declines (Hodgkin's disease, cervical cancer, peptic ulcer, and tuberculosis). Indeed, the number of cases of tuberculosis began falling in each group early in the 20th century even before effective therapy was available (Ewbank 1994, 123; Farley and Allen 1987, 42–3). Other causes have shown little or no change (breast cancer, appendectomy, cholecystectomy and hernia, and maternal mortality). Of these, breast cancer has been of particular concern. There is reasonably persuasive evidence that mammography has lowered the death rate from breast cancer (Tabar et al. 2003). But African-American women have benefited less than white women because they tend to be screened less frequently, to have lower rates of repeat mammography, and to have fewer follow-up examinations for abnormal findings (Jones, Patterson, and Calvocoressi 2003). Factors such as breast density and obesity, which are more common among African-American than white women, may also reduce the efficacy of mammography when it is used. Thus the story is complicated, but the evidence suggests that programs specially targeted to African-American women do increase the use of mammography and may well be beneficial (Jones, Patterson, and Calvocoressi 2003).

Unlike the preceding conditions, there has been a noticeable increase in asthma mortality among both African Americans and whites, although greater in the former than the latter. Hospital admissions for acute asthmatic attacks are much more common for African-American than for white youngsters and are much more common from inner-city than from other urban or suburban neighborhoods. It has been suggested that both adverse environmental conditions and lower-quality primary care are responsible for the differences (McConnochie et al. 1999).

HIV/AIDS and diabetes, two of the causes of death that account for much of the difference between white and African-American life expectancy, were not mentioned by the European Community Consensus Conference (Wong et al. 2002). Nonetheless, there is reason to believe that the health care system has much to offer in each case with regard to advice about prevention and treatment. Since 1980, the increase in both HIV/AIDS and diabetes has been more dramatic for African Americans than for whites. In the case of HIV/AIDS, however, there has been a sharp decline in mortality since the 1990s, the result of both preventive and therapeutic interventions (Wong et al. 2002). This decline parallels the accelerating drop in the death rate from tuberculosis in the same period, suggesting that the two are associated. In the case of diabetes, there has been no such decline. Indeed, the number of deaths from diabetes has been much higher for African Americans than for whites, and the evidence suggests that blacks are admitted to hospital with advanced disease requiring amputation more frequently than whites are (Gittelsohn, Halpern, and Sanchez 1991).

It is difficult to say definitively how much of the disparity in death rates from conditions amenable to health care interventions is the result of unequal access to the full range of health services and how much is due to circumstances beyond the reasonable reach of health care systems. Insurance (or its lack) has an important impact on access to care but does not explain all the racial differences in access that have been reported (Zuvekas and Taliaferro 2003). Nonetheless, such consistent differences lead to the conclusion that a great deal is indeed due to unequal access, much of which is built into patterns of segregation in both urban and rural America.

In addition, there is evidence that (1) the quality of primary care physicians who treat most African Americans may not be as good as that of other physicians (Bach et al. 2004) and that (2) even when whites and African Americans have similar types of health care coverage—for example, Medicare—and are admitted to hospitals, the care they receive differs. Notwithstanding the importance of Medicare as an integrative force in health care (Marmor 2000b), studies of Medicare fee-for-service and managed care programs still reveal “differences in care patterns … for cancer treatment, treatment after acute myocardial infarction, use of surgical procedures, hospice use, and preventive care” (Virnig et al. 2002, 224).

These differences may result from the providers’ racism, the patients’ lack of information, and differences in Medigap coverage, as well as other causes. Whatever the reason, as David Barton Smith (1998) showed, many of these differences in quality of hospital care can be attributed to the lax enforcement of requirements for equal treatment in facilities receiving federal funds. After a brief burst of enthusiasm for civil rights following the passage of Medicare in 1965, the federal enforcement of equal treatment in hospitals weakened. Smith cited several reasons why this occurred, among which were the executive branch's diminished commitment to civil rights enforcement, the growing preoccupation with cutting costs and shrinking the federal bureaucracy, and organizational changes within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This contributed to continuing disparities in the treatment of African Americans and whites. Thus even when mechanisms exist for enforcing equal treatment, the federal government has failed to make adequate use of them.

Compulsory Health Insurance in Canada and the United States

If the health disparities between African Americans and whites were caused by the institutional and policy legacy of slavery and racism, how that legacy was expressed was determined by political institutions. These same institutions also contribute much to the differences between the United States and Canada. An important feature of the American presidential system is that “individual members of the legislature owed their primary loyalty to their constituencies” (Huntington 1966, 390–1), powers are divided among the branches of the government, and party discipline is weak. According to Huntington (1966), this system, inherited from the Tudor model of government, was made obsolete by the parliamentary revolution in England just as it was being adopted in the United States. This is the system that made the influence of southern legislators so formidable.

In contrast to the presidential system, the parliamentary system centralized authority in Britain's Parliament. Members of Parliament were no longer responsible primarily to their constituencies but to the nation as a whole (Huntington 1966, 396); executive and legislative powers were merged; and policymaking was “concentrated in a relatively small and cohesive Cabinet, and the crucial debate on issues comes before they are presented in the legislature for consideration” (Maioni 1998, 23). Party discipline is strong, which means that dissidents within a political party may be forced to look elsewhere “rather than try to influence major parties from within” (Maioni 1998, 24). Third parties are thus more likely to emerge and persist in this sort of system than in the presidential system, in which party discipline is much weaker and the parties far more diverse.

Canada adopted the parliamentary system, and institutionalists argue that the difference in the U.S. and Canadian political systems helps explain the creation of national health insurance in Canada and its failure in the United States (Hacker 1998; Maioni 1998). But as the American example should have made clear, the larger political culture and economy have also had a profound effect. The absence of a social democratic party in the United States is an important reason why there is no compulsory health insurance, and the fact that the United States does not have a parliamentary system may partly explain why it does not have a social democratic third party (Gutman 1976; Lipset and Marks 2000; Sombart 1906). It does not explain, however, either why one of the two major American parties is not social democratic (Lipset and Marks 2000, 79–81) or why the most important third party in Canada is.

Having summarized a large body of this literature and even after recognizing great similarities in the two countries, Seymour Martin Lipset concluded:

The United States and Canada remain two nations formed around sharply different organizing principles. Their basic myths vary considerably, and national ethoses and structures are determined in large part by such images. One nation's institutions reflect the effort to apply universalistic principles emphasizing competitive individualism and egalitarianism, while the other's are an outgrowth of a particularistic compact to preserve linguistic and provincial cultures and rights and elitism. Ironically, … the conservative effort has stimulated an emphasis on group rights and benefits for the less privileged; the liberal one continues to stress more concern for the individual but exhibits less interest in those who are poor and outcast.

(Lipset 1990, 225)

In both French-speaking Quebec and English-speaking Canada, a certain degree of conservative collectivism has been prominent, that is, the belief that the state has the duty to intervene in economic affairs, that the collectivity takes precedence over individuals, and that society is necessarily hierarchical (Hall 2003). According to this explanation, socialism in Canada resulted from Tory collectivism and could develop only where collectivist traditions already existed. In the case of English-speaking Canada, the development of socialism also was encouraged by the immigration of British socialists, who were not foreign in their country in the same way that European socialists were alleged to be foreign in the United States (Horowitz 1968).

Another important part of the story is federalism. If race and the unjust treatment of African Americans are still among the great unresolved moral and political dilemmas in the United States, regionalism is the great unresolved issue in Canada (Myles 1996, 128). Morton Weinfeld noted that “the binational origin of the Canadian state paved the way for full acceptance of the plural nature of Canadian society and acknowledgment of the contributions, value, and rights of all Canadian minority groups.” Moreover, the binational origin of the state and “the fact that Canada's largest minority, French Canadians, control a province, Quebec,” mean that Canadian federalism is more fissiparous than the American version has been since the Civil War (quoted in Lipset 1990, 173). And, Lipset continued, “smaller provinces seeking to extend their autonomy have been able to do so because Quebec has always been in the forefront of the struggle” (Lipset 1990, 197). The nature of Canadian federalism, the presence of a social democratic party at both the provincial and federal levels (Kuderle and Marmor 1982, 12), and the role of the welfare state in tying together the country all go a long way toward explaining the passage of national health insurance in Canada (Kuderle and Marmor 1982, 89).

Not all Canadian scholars agree that social democracy was crucial to the development of the welfare state in Canada. Some claim that the social democrats (the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, or CCF) had no impact on Liberal policies in the 1940s (Brodie and Jenson 1980). Moreover, not all of Canada's generally redistributive welfare policies were influenced by the social democrats (Kuderle and Marmor 1982, 111). Nonetheless, with respect to national health insurance, it is significant that the socialist government of Saskatchewan was the first in North America to attempt to introduce social insurance, starting with universal, publicly administered hospital coverage in 1947 and followed by more complete protection in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Badgley and Wolfe 1967; Lipset 1950; Roth et al. 1953). A detailed history of health care in Saskatchewan is unnecessary here. The key point is that pioneering policies pursued in Saskatchewan had a considerable impact on the whole nation (Gray 1991; Hacker 1998; Porter 1965, 378; Taylor 1978). Despite the turmoil of the doctors’ strike of 1962, for instance, the essentials of Saskatchewan's plan for reimbursing physicians were adopted across the nation several years later. Despite business opposition, as well as Conservative opposition at the provincial level, Conservatives at the federal level were virtually unanimous in their support of both hospital insurance in the 1950s and physician reimbursement plans in 1972, a unanimity made possible by the party discipline that can be enforced in parliamentary systems like Canada's.

Moreover, opposition from the Canadian Medical Association, although very stiff, never reached the level of the invective or red-baiting used by the American Medical Association in its opposition to any form of government support of health insurance from the 1930s through the 1960s (Naylor 1986, 252). Indeed, two of the administrators of Saskatchewan's health program in the late 1940s were American believers in socialized medicine who presumably left their own country for a more hospitable climate (Lipset 1950, 270). In addition, Saskatchewan's original health care plan was based on the report of a committee chaired by Johns Hopkins University professor Henry Sigerist, who left the United States for Switzerland shortly after World War II when the political climate became increasingly unfriendly. Just as American attitudes toward race, as expressed through political institutions, contribute much to the differences in health between African Americans and whites, so have the differences between the American and Canadian political cultures and institutions greatly affected the differences in health care and mortality in the two countries.

Mortality of Canadians and White Americans

Figure 2 shows that the life expectancy of Canadians and white Americans diverged in the 1970s and that the difference has increased subsequently in each decade since then. Significantly, the differences between social insurance coverage in the two countries became apparent in the 1950s, when Canada instituted broader protection than the United States offered. By then, both countries had industrial accident, pension, and unemployment insurance, but in 1944 Canada also offered a system of family allowances. The gap in social insurance opened much wider after Canada implemented a universal health insurance program in 1972 (Kuderle and Marmor 1982, 83–5), in contrast to the far from universal programs, Medicare and Medicaid, created in the United States in 1965.

In addition, Canada's social insurance programs are more redistributive than America's, and the result has been much greater income equality in the former than the latter country. Although between 1974 and 1985, income inequality worsened in both Canada and the United States, the trend in Canada reversed in the following decade, whereas it continued in the United States. Between 1985 and 1997, Canadian patterns of income taxation and transfer payments were far more redistributive than those in the United States (Wolfson 2000; Wolfson and Murphy 2000).

After universal health insurance was implemented in Canada, several studies were made of the consequences for health care utilization. The results were mixed. Some showed that the inequalities among income groups in utilization and health status have persisted (Dunlop, Coyte, and McIsaac 2000; Dunn and Hayes 2000; Wilkins, Berthelot, and Ng 2002; Wood et al. 1999), but for the most part, utilization has increased, especially among the poor (McDonald et al. 1974; Munan, Vobecky, and Kelly 1974; Siemiatycki, Richardson, and Pless 1980). Although waiting times for elective and semiurgent procedures have lengthened since the 1970s, the degree to which the increase has reduced life expectancy, as contrasted with quality of life, is not significant (Naylor 1999). Moreover, (1) the differences among socioeconomic groups with respect to avoidable hospitalizations are far greater in American than in Canadian cities (Billings, Anderson, and Newman 1996); (2) the risk of inadequate prenatal care is greater for poor American women than for poor Canadian women (Katz, Armstrong, and LoGerfo 1994); (3) survival from some heavily technology-dependent conditions, for example, end-stage renal disease, is better in Canada than in the United States (Hornberger, Garver, and Jeffery 1997), perhaps the result of the high prevalence of for-profit dialysis centers in the United States; and (4) among hospitalized victims of myocardial infarction, Americans have more technologically intense interventions than Canadians but the same one-year survival (Anderson, Newhouse, and Roos 1989; Tu et al. 1997). In contrast, survival from hip fractures is worse in Manitoba than in New England (Roos et al. 1990), although comparisons with adjacent U.S. states might have been more appropriate. In general, however, most causes of death as well as mortality differences among income groups in Canada have declined since the 1970s (Wilkins, Berthelot, and Ng 2002). Furthermore, the use of U.S. services by Canadians is too small to have had a measurable impact on cause-specific mortality or life expectancy (Katz et al. 2002).

Several comparative studies (Gorey et al. 1997, 1998, 2000a, 2000b, 2003) of the association between income and survival rates from various cancers in American and Canadian cities revealed that

There were few, if any, differences in the survival of different income groups in Canada but very substantial differences in the United States.

People with cancer who came from poor populations in the United States had a worse chance of survival than did equally poor people in Canada. This was as true for poor whites as it was for poor African Americans.

In general, when only middle- and upper-income groups were considered, the differences in survival between the two countries were not significant, either statistically or substantively. Survival among the wealthiest groups in Honolulu was better than in Toronto, however.

Cancer survival patterns in Honolulu were more nearly like the patterns in Toronto than were those of any other American city. Because Hawaii is the one American state that has attempted—though with only partial success—to implement universal medical insurance, the evidence suggests that the differences in cancer survival documented in these studies were primarily the result of differences in access to health services.

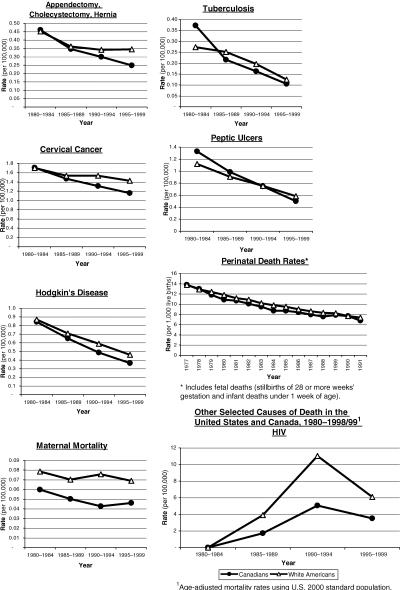

Similarly suggestive evidence of the importance of universal coverage comes from a comparison of changing Canadian and American mortality rates from 1980–84 to 1995–96, from causes of death amenable to intervention by the health care system. Douglas Manuel and Yang Mao (2002) showed the following:

The death rates of breast cancer, Hodgkin's disease, and peptic ulcer fell equally and were essentially indistinguishable in each country.

The number of asthma deaths rose in the United States and dropped in Canada.

The death rates of cervical cancer, hypertension/cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, tuberculosis, and appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hernia fell in each country, but more rapidly and to lower levels in Canada than in the United States.

These observations suggest, too, that the Canadian system of comprehensive care, free of charge at the point of service, and with a greater emphasis than in the United States on primary care, may be generally more effective than the American system for the total population. In light of the great inequalities between whites and African Americans, however, the question is whether the differences between the two countries can be explained by the high rates of death among African Americans or whether these differences affect white Americans as well. Both the lower life expectancy of white Americans than Canadians since the 1970s and the results of the analyses of cancer survival suggest that there should be differences in most of the causes of death amenable to intervention by the health care system. This is important, because if the U.S.-Canadian differences can be explained only by the high rates of preventable deaths among African Americans, then equality between the United States and Canada could be addressed by equalizing the care received by African Americans and leaving the rest of the system untouched. But if the U.S.-Canadian differences are also attributable to differences between white Americans and Canadians, then equalization would require more than simply addressing the problems affecting African Americans, important though that is as an end in itself.

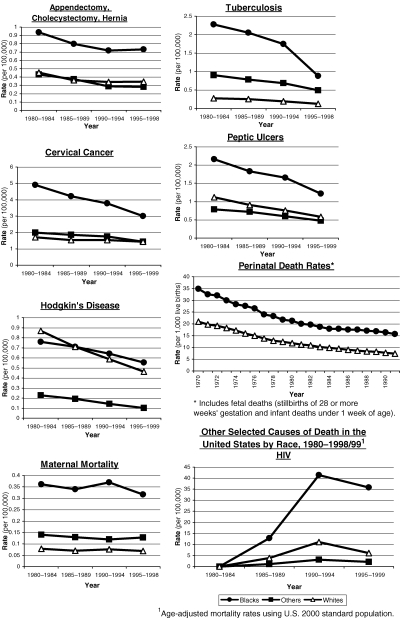

Figure 4 compares the age-adjusted death rates of Canadians (Statistics Canada 1980–99) and white Americans from the same causes as those described previously when African-American and white rates were compared. In virtually every case, Canadians have lower rates than white Americans. The exceptions are breast cancer, all respiratory diseases in children, and peptic ulcer, for which the rates are very similar or the same. Moreover, in those conditions for which the rates are falling, they tend to be falling more rapidly among Canadians. These conditions are hypertension and cerebrovascular disease, Hodgkin's disease, appendectomy, cholecystectomy and hernia, cervical cancer, and chronic rheumatic heart disease. Ischemic heart disease has fallen at about the same rate in each population. HIV/AIDS mortality increased more rapidly and to higher levels among white Americans than Canadians, and in the 1990s it fell more rapidly. Nonetheless, the rates still are higher in the United States. Diabetes mortality is increasing in both populations as well, but far more rapidly among white Americans than among Canadians.

Figure 4.

Avoidable Mortality in the United States and Canada, 1980–1998/991

These comparisons strongly suggest that the Canadian health care system, though not without serious problems (Blumenthal et al. 2004), serves the interests of Canadians better than the U.S. health care system serves the interests of white Americans, not to mention African Americans. Even the use of American-made pharmaceuticals does not seem to have led to higher death rates in Canada, which should allay the fears of those concerned about reimporting drugs to the United States from Canada. Moreover, the lower death rates of Canadians have been achieved at about half the cost of what Americans pay for health care (Reinhardt, Hussey, and Anderson 2004). In 1999, in current U.S. dollars, the per capita health expenditures in Canada were $1,939, compared with $4,271 in the United States (World Bank 2003).

Conclusion

Random assignment of race and citizenship being an impossibility, comparisons like those in this article are fraught with difficulties. Even when considering particular types of institutions, such as hospitals, and specific conditions, such as myocardial infarctions and fractured hips, it is difficult to be certain that they are truly comparable. Nonetheless, the reported differences between whites and African Americans and between white Americans and all Canadians in causes of death that a well-functioning health system ought to be expected to address are consistent, which raises questions about the impact of health services that cannot simply be dismissed. Beginning in the last third of the 19th century, public health interventions have had a major impact on mortality (e.g., Cain and Rotella 2001; Condran 1987; Condran and Cheney 1982; Condran and Crimmins-Gardner 1978; Crimmins and Condran 1983; Fulton 1980; Wells 1995), and evidence strongly supports the effect of health services on population mortality in the late 20th century (McKee 1999; Nolte and McKee 2004).

Clearly, much more than unequal access to health services, no matter how broadly construed, accounts for the disparities I have reported between whites and African Americans, but health services cannot simply be deemed insignificant. In contrast, more of the disparity between white Americans and Canadians seems to be attributable to access to health services, largely because the timing of the divergence coincides so closely with the creation of universal coverage in Canada, and because the difference is so much smaller. Other factors must also be important. Among the most frequently cited is income inequality. I noted earlier that income inequality is greater in the United States than in Canada, the result of the same differences in political culture and institutions that led to such different health care systems. It is thus difficult to disentangle the effects of income inequality and health services. But the evidence cited here regarding patterns of survival of cancer patients with similar incomes in the two countries, as well as differences in prenatal care among poor women in the two countries, suggests that the impact of health care is significant apart from the fact of income inequality. Although I do not claim that all the disparity is due to differences in access to services, I do believe that the evidence is highly suggestive and that those who disagree must demonstrate that there is no effect.

While the emergence of North American welfare states has had profound and generally beneficial consequences for the health of their populations, in the United States these benefits have been achieved very unequally. The founding legislation of the American welfare state contained discriminatory policies that have cast long shadows right into the 21st century. Even when those policies have been reversed in law, equal rights have not been rigorously enforced. Not only have African Americans experienced the injustice and indignity of segregation and discrimination, but the same forces that enabled their exclusion also contributed to the failure of white Americans to realize fully the benefits of a universally accessible health care system.

Although the past has shaped the present, the future is not immutable. Unfortunately, the Canadian system of health care is more likely to become like the American system than the American system is to become like the Canadian, because parliamentary systems are better able to change direction than the American system is. A cohesive and tightly disciplined party structure, the very feature of the Canadian system that made dramatic change possible in the first place, may make a change of direction more likely. It is significant, for instance, that among the nations studied by Evelyn Huber and John Stephens (2001), the two countries that most radically restricted their relatively generous welfare states in the 1980s were New Zealand and the United Kingdom, both with parliamentary systems. Admittedly, another important factor is that each is a unitary state rather than a federation like Canada, Australia, or the United States (Huber and Stephens 2001, 307). Nonetheless, in comparison with the system in the United States, the Canadian system is likely to be able to be changed more quickly and more radically, both to expand and to contract benefits. Indeed, the American system was designed to make radical changes in policy difficult. Regardless of the permanence or impermanence of the Canadian system of health care, however, the inability to create a similar universal health care system in the United States has had a measurable impact on the health of all Americans over the past 30 years.

Acknowledgments

Theodore Marmor, David Mechanic, and Jill Quadagno provided helpful suggestions. The research on which this paper is based was supported by a Health Policy Investigator Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

References

- Anderson GM, Newhouse JP, Roos LL. Hospital Care for Elderly Patients with Diseases of the Circulatory System: A Comparison of Hospital Use in the United States and Canada. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321:1443–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911233212105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach PB, Pham HM, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary Care Physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:575–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgley RF, Wolfe S. Doctors’ Strike: Medical Care and Conflict in Saskatchewan. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Sudano JJ, Albert JM, Borawski EA, Dor A. Loss of Health Insurance and the Risk for a Decline in Self-Reported and Physical Functioning. Medical Care. 2002;40:1126–31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltzell ED. The Protestant Establishment: Aristocracy and Caste in America. New York: Random House; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Beckert S. The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Billings J, Anderson GM, Newman LS. Recent Findings on Preventable Hospitalizations. Health Affairs. 1996;15:239–50. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon RJ, Aiken LH, Freeman HE, Corey CR. Access to Medical Care for Black and White Americans: A Matter of Continuing Concern. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261:278–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D, Vogeli C, Alexander L, Pittman M. A Five-Nation Hospital Survey: Commonalities, Differences, and Discontinuities. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MJ, Jenson J. Crisis, Challenge and Change: Party and Class in Canada. Toronto: Methuen; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd WM, Clayton LA. An American Health Dilemma: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race, Beginnings to 1900. London: Routledge; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain LP, Rotella EJ. Death and Spending: Urban Mortality and Municipal Expenditure on Sanitation. Annales de demographie historique. 2001;1:139–54. [Google Scholar]

- Carr W, Szapiro N, Heisler T, Krasner MI. Sentinel Health Events as Indicators of Unmet Needs. Social Science and Medicine. 1989;29:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Wonder. search program. [accessed December 9, 2004]. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov/#aboutWonder.

- Condran GA. Declining Mortality in the United States in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Annales de demographie historique. 1987;1:119–41. doi: 10.3406/adh.1988.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condran GA, Cheney RA. Mortality Trends in Philadelphia: Age- and Cause-Specific Death Rates 1870–1930. Demography. 1982;19:97–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condran GA, Crimmins-Gardner E. Public Health Measures and Mortality in U.S. Cities in the Late 19th Century. Human Ecology. 1978;6:27–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00888565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Condran GA. Mortality Variation in U.S. Cities in 1900. Social Science History. 1983;7:31–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop S, Coyte PC, McIsaac W. Socio-Economic Status and the Utilization of Physicians’ Services: Results from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:123–33. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JR, Hayes MV. Social Inequality, Population Health, and Housing: A Study of Two Vancouver Neighborhoods. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:563–87. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engerman SL, Haber SH, Sokoloff KL. Inequality, Institutions, and Differential Growth among New World Economies. In: Ménard C, editor. Institutions, Contracts and Organizations: Perspectives from New Institutional Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Engerman SL, Sokoloff KL. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2002. Factor Endowments, Inequality, and Paths of Development among New World Economies. Working paper 9259. [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank DC. History of Black Mortality and Health before 1940. In: Willis DP, editor. Health Policies and Black Americans. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction; 1994. 100–28. [Google Scholar]

- Farley R, Allen WR. The Color Line and the Quality of Life in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton JP. Socioeconomic Forces as Determinants of Childhood Mortality Decline in Rhode Island, 1860–1970: Comparison with England and Wales. Comparative Social Research. 1980;3:287–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn AM, Halpern J, Sanchez RL. Income, Race, and Surgery in Maryland. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:1435–41. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Holowaty EJ, Fehringer G, Laukkanen E, Moskowitz A, Webster DJ, Richter NL. An International Comparison of Cancer Survival: Toronto, Ontario, and Detroit, Michigan, Metropolitan Areas. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1156–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Holowaty EJ, Fehringer G, Laukkanen E, Richter NL, Meyer CM. An International Comparison of Cancer Survival: Metropolitan Toronto, Ontario, and Honolulu, Hawaii. American Journal of Public Health. 2000a;90:1866–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Holowaty EJ, Fehringer G, Laukkanen E, Richter NL, Meyer CM. An International Comparison of Cancer Survival: Toronto, Ontario, and Three Relatively Resourceful United States Metropolitan Areas. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2000b;22:343–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Holowaty EJ, Laukkanen E, Fehringer G, Richter NL. An International Comparison of Cancer Survival: Advantage of Toronto's Poor over the Near Poor of Detroit. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1998;89:102–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03404398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Kliewer E, Holowaty EJ, Laukkanen E, Ng EY. An International Comparison of Breast Cancer Survival: Winnipeg, Manitoba and Des Moines, Iowa, Metropolitan Areas. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003;13:32–41. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham DW. The South in Modern America. New York: HarperCollins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gray G. Federalism and Health Policy: The Development of Health Systems in Canada and Australia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman HG. Work, Culture, and Society in Industrializing America. New York: Knopf; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JS. The Historical Logic of National Health Insurance: Structure and Sequence in the Development of British, Canadian and U.S. Medical Policy. Studies in American Political Development. 1998;12:57–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley J, Steinberg EP, Feder J. Comparison of Uninsured and Privately Insured Hospital Patients: Condition on Admission, Resource Use, and Outcome. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265:374–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MR, Steckel RH, editors. A Population History of North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall AJ. The American Empire and the Fourth World. Montreal: McGill–Queens University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hart K, Kunitz SJ, Mukamel D, Sell R. Metropolitan Governance, Residential Segregation, and Mortality among African Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:434–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland WW. European Community Atlas of “Avoidable Death.”. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger JC, Garver AM, Jeffery JR. Mortality, Hospital Admissions, and Medical Costs of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States and Manitoba, Canada. Medical Care. 1997;35:686–700. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz G. Canadian Labour in Politics. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert D. Perinatal Mortality in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics. 1995;20(25) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber E, Stephens JD. Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington SP. Political Modernization: America vs. Europe. World Politics. 1966;18:378–414. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KT. Crabgrass Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SA, Anderson RT, Johnson NJ, Sorlie PD. The Relation of Residential Segregation to All-Cause Mortality: A Study in Black and White. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:615–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BA, Patterson EA, Calvocoressi L. Mammography Screening in African American Women: Evaluating the Research. Cancer. 2003;97(suppl.):258–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, Lynch JW, Cohen RD, Balfour JL. Inequality in Income and Mortality in the United States: Analysis of Mortality and Potential Pathways. BMJ. 1996;312:999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SJ, Armstrong W, LoGerfo JP. The Adequacy of Prenatal Care and Incidence of Low Birthweight among the Poor in Washington State and British Columbia. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:986–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SJ, Cardiff K, Pascali M, Barer ML, Evans RG. Phantoms in the Snow: Canadians’ Use of Health Care Service in the United States. Health Affairs. 2002;21:19–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katznelson I, Geiger K, Kryder D. Limiting Liberalism: The Southern Veto in Congress, 1933–1950. Political Science Quarterly. 1993;108:283–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kuderle RT, Marmor TR. The Development of Welfare States in North America. In: Flora P, Heidenheimer AJ, editors. The Development of Welfare States in Europe and America. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction; 1982. pp. 81–121. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA. Linking Residential Segregation to the Infant Mortality Race Disparity in U.S. Cities. Sociology and Social Research. 1989;73:90–4. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA. Segregation, Poverty, and Empowerment: Health Consequences for African Americans. Milbank Quarterly. 1993;71:41–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman RC. Shifting the Color Line: Race and the American Welfare State. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset SM. Agrarian Socialism. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset SM. Continental Divide: The Values and Institutions of the United States. New York: Routledge; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset SM, Marks G. It Didn't Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States. New York: Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Maioni A. Parting at the Crossroads. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel D, Mao Y. Avoidable Mortality in the United States and Canada, 1980–96. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1481–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmor TR. The Politics of Medicare. 2nd ed. Chicago: Aldine; 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Marmor TR. Review of Atlantic Crossings and Shifting the Color Line. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2000b;64:110–3. [Google Scholar]

- McConnochie KM, Russo MJ, McBride J, Szilagy P, Brooks AM, Roghmann KJ. Socioeconomic Variations in Asthma Hospitalization: Excess Utilization or Greater Need? Pediatrics. 1999;103:e75. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord C, Freeman HP. Excess Mortality in Harlem. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;322:173–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001183220306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AD, McDonald JC, Salter V, Enterline PE. Effects of Quebec Medicare on Physician Consultation for Selected Symptoms. New England Journal of Medicine. 1974;291:649–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197409262911304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M. Does Health Care Save Lives? Croatian Medical Journal. 1999;40:123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munan L, Vobecky J, Kelly A. Population Health Care Practices: An Epidemiologic Study of the Immediate Effects of a Universal Health Insurance Plan. International Journal of Health Services. 1974;2:285–95. doi: 10.2190/07VG-VTDP-400P-450V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles J. When Markets Fail: Social Welfare in Canada and the United States. In: Esping-Andersen G, editor. Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies. London: Sage; 1996. pp. 116–40. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor CD. Private Practice, Public Payment: Canadian Medicine and the Politics of Health Insurance 1911–1966. Montreal: McGill–Queens University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor CD. Health Care in Canada: Incrementalism under Fiscal Duress. Health Affairs. 1999;18:9–26. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte E, McKee M. Does Healthcare Save Lives? Avoidable Mortality Revisited. London: Nuffield Trust; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M, Shapiro T. Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. New York: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Polednak AP. Black-White Differences in Infant Mortality in 38 Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:1480–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polednak AP. Poverty, Residential Segregation, and Black/White Mortality Ratios in Urban Areas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1993;4:363–73. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polednak AP. Segregation, Poverty and Mortality in Urban African Americans. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. The Vertical Mosaic. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Quadagno J. The Color of Welfare: How Racism Undermined the War on Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS, Anderson GF. U.S. Health Care Spending in an International Context: Why Is U.S. Spending So High, and Can We Afford It? Health Affairs. 2004;23:10–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rene AA, Daniels DE, Jones W, Jr, Jiles R. Mortality Preventable by Medical Interventions: Ethnic and Regional Differences in Texas. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1995;87:820–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos LL, Fisher ES, Sharp SM, Newhouse JP, Anderson G, Bubolz TA. Postsurgical Mortality in Manitoba and New England. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;263:2453–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth FB, Meyers GW, Mott FD, Rosenfield LS. The Saskatchewan Experience in Payment for Hospital Care. American Journal of Public Health. 1953;43:752–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.43.6_pt_1.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusk D. Cities without Suburbs. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E, Kofie VY, Rivo M, Tuckson RV. Black/White Comparisons of Deaths Preventable by Medical Intervention: United States and the District of Columbia 1980–1986. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;19:591–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro TM. The Hidden Cost of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Siemiatycki J, Richardson L, Pless IB. Equality in Medical Care under National Health Insurance in Montreal. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303:10–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007033030103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB. Addressing Racial Inequality in Health: Civil Rights Monitoring and Report Cards. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1998;23:75–105. doi: 10.1215/03616878-23-1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sombart W. Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? London: Macmillan; 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Causes of Death. Ottawa: 1980. –99. [Google Scholar]

- Tabar L, Yen M-F, Vitak B, Chen H-HT, Smith RA, Duffy SW. Mammography Service Screening and Mortality in Breast Cancer Patients: 20-Year Follow-up before and after Introduction of Screening. The Lancet. 2003;361:1405–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MG. Health Insurance and Canadian Public Policy: The Seven Decisions That Created the Canadian Health Insurance System. Montreal: McGill–Queens University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tu JV, Pashos CL, Naylor CD, Chen E, Normand S-L, Newhouse JP, McNeil BJ. Use of Cardiac Procedures and Outcomes in Elderly Patients with Myocardial Infarction in the United States and Canada. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:1500–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705223362106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virnig BA, Lurie N, Huang Z, Musgrave D, McBean AM, Dowd B. Racial Variations in Quality of Care among Medicare+Choice Enrollees. Health Affairs. 2002;21:224–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells RV. The Mortality Transition in Schenectady, New York, 1880–1930. Social Science History. 1995;19:399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Wenneker MB, Epstein AM. Racial Inequalities in the Use of Procedures for Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease in Massachusetts. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteis DG. Third World Medicine in First World Cities: Capital Accumulation, Uneven Development and Public Health. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:795–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins R, Berthelot J-M, Ng E. Trends in Mortality by Neighbourhood Income in Urban Canada from 1971 to 1996. Vol. 13. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2002. Suppl. to Health Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M. The Daily. Statistics Canada; 2000. [accessed July 28, 2004]. Income Inequality in Canada and the United States. Available at http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/000728/d000728a.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M, Murphy B. Income Inequality in North America: Does the 49th Parallel Still Matter? Canadian Economic Observer. 2000:1–24. August. [Google Scholar]

- Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of Major Diseases to Disparities in Mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1585–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Sallar AM, Schechter MT, Hogg RS. Social Inequalities in Male Mortality Amenable to Medical Intervention in British Columbia. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:1751–8. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Silber R, Bader M, Harnly M, Jones AA. Medical Care and Mortality: Racial Differences in Preventable Deaths. International Journal of Health Services. 1985;15:1–22. doi: 10.2190/90P3-LEFF-WNU0-GLY6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators 2002. Washington, D.C.: 2003. CD-ROM. [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Taliaferro GS. Pathways to Access: Health Insurance, the Health Care Delivery System, and Racial/Ethnic Disparities, 1996–1999. Health Affairs. 2003;22:139–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]