Abstract

Context: The human adrenal gland produces small amounts of testosterone that are increased under pathological conditions. However, the mechanisms through which the adrenal gland produces testosterone are poorly defined.

Objective: Our objective was to define the role of type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3) in human adrenal production of testosterone.

Design and Methods: Adrenal vein sampling was used to confirm ACTH stimulation of adrenal testosterone production. Adrenal expression of AKR1C3 was studied using microarray, quantitative real-time RT-PCR, and immunohistochemical analyses. AKR1C3 knockdown was accomplished in cultured adrenal cells (H295R) using small interfering RNA, followed by measurement of testosterone production.

Results: Acute ACTH administration significantly increased adrenal vein testosterone levels. Examination of the enzymes required for the conversion of androstenedione to testosterone using microarray analysis, quantitative real-time RT-PCR, and immunohistochemistry demonstrated that AKR1C3 was present in the adrenal gland and predominantly expressed in the zona reticularis. Decreasing adrenal cell expression of AKR1C3 mRNA and protein inhibited testosterone production in the H295R adrenal cell line.

Conclusions: The human adrenal gland directly secretes small, but significant, amounts of testosterone that increases in diseases of androgen excess. AKR1C3 is expressed in the human adrenal gland, with higher levels in the zona reticularis than in the zona fasciculata. AKR1C3, through its ability to convert androstenedione to testosterone, is likely responsible for adrenal testosterone production.

AKR1C3 is expressed in the human adrenal reticularis and plays a role in adrenal testosterone production.

The human adrenal zona reticularis (ZR) produces the so-called adrenal androgens dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (1,2). Although the factors leading to the production of adrenal androgen production are unclear, ACTH does play a key role in regulating DHEA production (2). Testosterone, a more active androgen, is primarily produced in the testis and, to some degree, the ovary, under the control of LH (2). However, several studies have shown that the adrenal gland contributes to the circulating pool of testosterone by direct secretion as well as by peripheral conversion of adrenal-derived precursor (3,4,5). Adrenal synthesis of testosterone is also elevated in some women with androgen excess associated with hirsutism and polycystic ovarian syndrome (6,7). Despite the potential importance of adrenal testosterone as a source of androgen in female androgen excess, the adrenal enzymes involved in testosterone synthesis remain poorly defined.

The high expression of type 3 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD17B3), which converts androstenedione to testosterone, is necessary for the level of testosterone produced in the testis. However, expression of this enzyme is highly restricted to the testis, and therefore, testosterone production in other tissues has recently been attributed to type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, also called aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) (6,8,9,10). AKR1C3 is expressed in many tissues, including skeletal muscle, liver, adrenal gland, and ovary (11). However, to date, there have been no studies of human adrenal AKR1C3 expression. Herein, we show that the adrenal cortex expresses AKR1C3, with highest levels seen in the ZR. In addition, we show that decreasing levels of AKR1C3 in adrenocortical cells inhibits production of testosterone. These findings support a role for AKR1C3 in human adrenal production of testosterone and suggest that further studies are warranted to define the role of adrenal AKR1C3 as it relates to androgen excess.

Materials and Methods

Human tissue preparation

Whole human adult adrenal gland, liver, testis, and pre- and postmenopausal ovaries were obtained through the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (Philadelphia, PA), Clontech (Palo Alto, CA), and Tohoku University School of Medicine. The use of these tissues was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Medical College of Georgia and Tohoku University School of Medicine. The tissues were kept frozen for subsequent RNA extraction or for cell isolation. Adult adrenal tissues were also fixed with 10% formaldehyde for immunohistochemistry. The method of RNA extraction was previously reported in detail (12). In addition, for microarray analysis, isolated RNA from human adrenal zona fasciculata (ZF) (n = 3) and ZR (n = 3) was prepared by microdissection of the adrenal gland as previously described (13).

Microarray and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) analyses for adrenal ZF and ZR cells

ZF and ZR cell RNA was analyzed using an Affymetrix human HG-U133 + 2 oligonucleotide microarray set containing 54,675 probe sets, representing approximately 40,500 independent human genes. The arrays were scanned at high resolution using an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 located at Medical College of Georgia Microarray Core Facility. Results between arrays were studied with GeneSpring GX 7.3 software (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA) using a gene list of steroidogenic enzymes that included 44 genes. To confirm the result of microarray analysis, qPCR analysis was performed using ZF and ZR cell RNA for AKR1C3, type 2 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B2), and cytochrome b5 (CYB5). The sequences for primers and probes for HSD3B2 and CYB5 were previously described in detail (14,15). The protocol of cDNA synthesis was previously described in detail (12). qPCR were performed using the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative normalization of cDNA in each tissue-derived sample was performed using expression of 18S rRNA as an internal control. After quantitative normalization, the expression of each gene was compared as previously reported (12).

qPCR for aldo-keto reductase and hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase family members

As well as AKR1C3, it is reported that there are several enzymes that are currently known to have the ability to catalyze the conversion of androstenedione to testosterone, specifically type 1 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD17B1), HSD17B3, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C1 (AKR1C1), aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C2 (AKR1C2), and aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C4 (AKR1C4) (2,9,16). Therefore, the mRNA levels of AKR1C3 and these enzymes among different tissues were measured by qPCR analysis as described above. The primer/probe set for human AKR1C3 was designed as published previously (17). The primer set for AKR1C1 was designed as follows: forward, 5′-AAA GCC AGG TGA GGA AGT GA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CAT GTG GCA CAG AGA TCC AC-3′. HSD17B1, HSD17B3, AKR1C2, and AKR1C4 mRNA levels were measured using primers and probes from TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems).

Immunohistochemistry

The method for immunohistochemistry was previously reported in detail (12). A monoclonal antihuman AKR1C3 antibody was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). It was previously reported that this monoclonal antibody does not cross-react with human AKR1C1, AKR1C2, or AKR1C4 (18). The polyclonal antibody for HSD3B2 was kindly provided by Dr. Mason (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK). Negative control staining, in which primary antibody was replaced with PBS, was also performed, and no specific immunoreactivity was detected in these tissue sections (data not shown).

Transfection of AKR1C3 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and testosterone measurement in a human adrenocortical cell line (H295R)

The human adrenocortical cell line H295R was used for all transfection experiments and was routinely cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles/Ham F12 (DME/F12) medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2.5% Ultroser G (Life Sciences, Cergy, France), 1% ITS plus Universal Culture Supplement Premix (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), and antibiotics, including 1% penicillin/ streptomycin solution (Life Technologies, Inc.) and 0.1% gentamicin solution (Sigma-Aldrich). siRNA of AKR1C3 was commercially obtained from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). As a negative control, Stealth RNAi Negative Control Duplexes were also used (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Electrical transfection assays were performed using the Nucleofector System (AMAXA, Gaithersburg, MD). Briefly, cells were cultured to 80–90% confluence in growth medium and then trypsinized and resuspended in Nucleofector Solution R (AMAXA) at a ratio of 5 million cells per 100 μl solution. Indicated amounts of AKR1C3 siRNA or Stealth RNAi Negative Control Duplexes (10 nm at final concentration) were added to the solution, and the mixture was run under program T20 in the Nucleofection System. Cells were allowed to recover for 48 h before treatment. For treatment, H295R cells were then incubated for 48 h in a low-serum medium containing 0.1% Cosmic Calf serum (CCS) either under basal conditions or with forskolin (10 μm). To examine the potential role of AKR1C3 using a pharmacological approach, H295R cells were incubated for 48 h in a low-serum medium containing 0.1% Cosmic Calf serum either with or without indomethacin (10 μm; Sigma-Aldrich), which is known to inhibit AKR1C enzymes (19). The medium was collected, and testosterone was measured using RIA (Siemens, Tarrytown, NY). For testosterone measurement, 50 μl of each sample was incubated with [125I]testosterone in antibody-coated tubes for 3 h at 37 C and counted for 1 min in a γ-counter. The limit of quantification (LLQ) was 0.14 nmol/liter, and the coefficient of variation (CV) ranged from 6–12%. Both RNA and protein were isolated from the cells for qPCR and Western analysis. For Western analysis, a monoclonal human anti-AKR1C3 (Sigma-Aldrich) and a monoclonal human anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) were used.

Adrenal vein sampling (AVS) and measurement of serum testosterone

The premenopausal (n = 4) and postmenopausal female (n = 4) patients with primary aldosteronism had samples taken at Tohoku University Hospital from 2007–2008 via AVS as has previously been reported (20). Informed consent was also obtained from all the patients in AVS. During AVS, blood was collected from the bilateral adrenal veins and the iliac vein. In addition, simultaneous bilateral blood collection 15 min after 0.25 mg (10 IU) ACTH stimulation was also performed. Successful adrenal venous cannulation was confirmed based on the cortisol level after ACTH stimulation in the adrenal venous sample, which was more than five times higher than that in the vena cava samples (20). For our study, we used iliac and adrenal vein plasma from the normal adrenal opposite to the aldosterone-producing tumor side. The testosterone content of patient plasma was determined using a liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) analysis. Plasma aldosterone and cortisol were measured by SPAC-S Aldosterone Kit (TFB Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and fluorescence polarization immunoassay (Abbott Japan Co., Chiba, Japan), respectively. For aldosterone measurement, the LLQ was 2.5 ng/dl, and the CV ranged from 4.5–4.7%. For cortisol measurement, the LLQ was 0.7 μg/dl, and the CV was 20%.

LC-MS-MS sample preparation and analysis condition

Samples to be analyzed (200 μl) were processed by liquid/liquid extraction using 4 ml methyl tertiary butyl ether. Testosterone-2,2,4,6,6-d5 (T-d5) was used as the internal standard. The organic phase was evaporated to dryness and reconstituted in 100 μl water/acetonitrile (80:20), and 20 μl was analyzed on a Waters Xterra C18 (2.1 × 250 mm, 5 μm) column by reversed-phase HPLC (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, and Leap Technologies, Carrboro, NC) coupled with a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Beverly, MA) run in electrospray-positive mode. The column temperature was held at 40 C. The mobile phase was a gradient of 0.5% formic acid in water (vol/vol) and 0.5% formic acid in acetonitrile (vol/vol). The retention time for testosterone and T-d5 was 10.2 min. The LC-MS-MS transition for testosterone was 289.0–96.9 atomic mass units, and the transition for T-d5 was 294.0–99.8 atomic mass units. Calibration curves prepared in water and quality control (QC) samples prepared in human plasma from normal donors were analyzed in parallel with the samples. Sample responses were acquired, and concentrations were determined based on the calibration curve using Masslynx analysis software (Waters). The concentration of analyte in the QC samples was calculated by subtracting the mean endogenous concentration determined in normal donor plasma from the total concentration found in the QC sample.

Data analysis and statistical methods

Results are given as mean ± sem where appropriate. Statistical analyses were done by unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc test for comparisons between two groups dependent on the data types. Significance was accepted at the 0–0.05 level of probability (P < 0.05).

Results

Microarray and qPCR analysis using ZF and ZR cell RNA

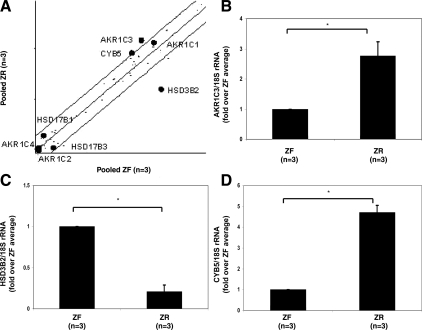

Four transcripts were found to have greater than a 2-fold difference in expression between ZR and ZF among 44 steroidogenic enzymes and related proteins (21). Among the transcripts that were preferentially expressed in the ZR were AKR1C3 and CYB5, which are known to be involved in androgen synthesis (Fig. 1A). AKR1C3 has many enzymatic activities, one of which is the ability to convert androstenedione to testosterone. HSD3B2, which is needed for glucocorticoid production, was expressed at levels 7-fold higher in ZF vs. ZR (Fig. 1A). These transcript differences were confirmed by qPCR using three different ZF and ZR sample pairs (Fig. 1, B–D).

Figure 1.

A, Scatter plot from microarray analysis comparing the mRNA normalized signal intensity for steroidogenic enzymes between human adrenal ZR (n = 3) and ZF cells (n = 3). Each spot represents a unique transcript, with a total of 44 steroid-metabolizing transcripts examined. Transcripts with the highest signal variation, AKR1C3, CYB5, and HSD3B2 transcripts are labeled. Microarray analysis was confirmed using qPCR specific for AKR1C3 (B), HSD3B2 (C), and CYB5 (D). qPCR was used to quantify the transcripts for these genes in the ZR (n = 3) and ZF cells (n = 3), as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as the fold over the average expression levels seen in the liver. mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA. *, P < 0.05.

AKR1C1 transcripts were also abundant in both the ZF and ZR; however, the expression levels were not significantly different between the ZF and ZR (Fig. 1A). Four other enzymes, HSD17B1, HSD17B3, AKR1C2, and AKR1C4, which have been reported to have the ability for androstenedione to testosterone conversion, showed very low expression signals in both the ZR and ZF (Fig. 1A).

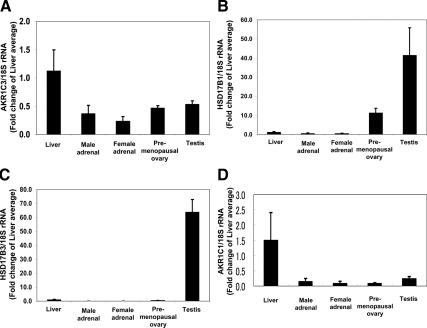

qPCR analysis using several human tissues

qPCR was used to compare mRNA levels for HSD17B1, HSD17B3, AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, and AKR1C4 among different human tissues. AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 mRNA was easily detectable in all tissues examined, but levels were lower in whole adrenal gland, compared with the liver (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). The levels of HSD17B1 and HSD17B3 mRNA were significantly higher in the testis compared with other tissues we studied (Fig. 2) (P < 0.05). HSD17B1 mRNA was also high in the ovary (Fig. 2). On the other hand, HSD17B1 and HSD17B3 transcripts were low in the adrenal gland (Fig. 2). These data support a broad expression pattern for AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 and a highly restricted pattern of expression for HSD17B1 and HSD17B3. The expression of AKR1C2 and AKR1C4 mRNA was very low or undetectable in human adrenal glands (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Quantification of AKR1C3 (A), HSD17B1 (B), HSD17B3 (C), and AKR1C1 (D) transcript levels in the human male and female adrenal (n = 6 each), liver, testis, and pre- and postmenopausal ovary (n = 3 each). qPCR was performed to quantify the level of the mRNA, as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as the fold over the average expression levels seen in the liver. mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA. *, P < 0.05.

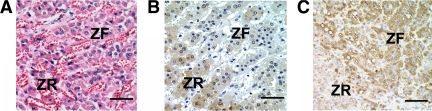

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of adrenal sections was performed to localize the expression of AKR1C3 and HSD3B2 within the human adrenal (Fig. 3). AKR1C3 immunoreactivity was predominantly detected in cytoplasm of the ZR in human adrenal gland (Fig. 3B). We also confirmed that HSD3B2 immunoreactivity was highly detectable in the ZF but not the ZR in human adrenals (Fig. 3C). The pattern of AKR1C3 immunoreactivity showed no significant difference related to sex or age (data not shown). No staining was observed in the absence of AKR1C3 antibody (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining (A) and immunohistochemical localization of AKR1C3 (B) and HSD3B2 (C) in the human adult adrenal gland. Bar, 10 μm. These are representative photomicrographs from the examination of 10 adrenals.

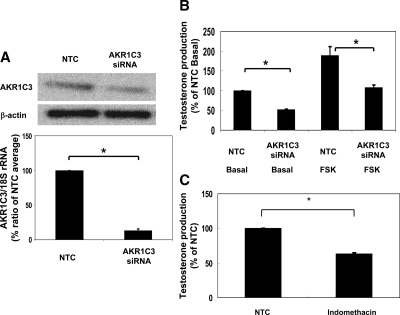

Testosterone production in H295R adrenal cells after AKR1C3 siRNA transfection

The H295R adrenal cell line produces a variety of androgens, including testosterone (22). After transfection of H295R cells with AKR1C3-specific siRNA, the levels of AKR1C3 mRNA dropped by 87% and protein level dropped by 40%, compared with control cells (Fig. 4A). Forskolin (used to activate cAMP-dependent pathways) increased H295R testosterone production by approximately 2-fold in cells transfected with scrambled (control) or siRNA directed at AKR1C3 (Fig. 4A). However, testosterone production was significantly lower (by 40%) in both AKR1C3 siRNA-transfected cells when compared with control cells (Fig. 4B). To examine the contribution of AKR1C3 to testosterone using a pharmacological strategy, H295R cells were incubated for 48 h in the absence and presence of indomethacin (10 μm). Testosterone production was significantly inhibited (by 35%) by indomethacin treatment compared with control cells (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Effects of siRNA depletion of AKR1C3 on adrenal cell production of testosterone. A, H295R adrenal cells were transfected with or without siRNA against AKR1C3 (AKR1C3 siRNA) or Stealth RNAi Negative Control Duplexes (NTC). After 96 h, mRNA and protein for AKR1C3 were detected by qPCR and Western analyses, respectively. The 18s rRNA and β-actin protein expression were used for normalization. Data are presented as mean ± se of values from three independent experiments run and expressed as a percentage of NTC. *, P < 0.05, compared with NTC level. B, The level of testosterone in the media with H295R cells at 48 h after treatment with vehicle (basal) or forskolin (FSK) (10 μm) after AKR1C3 (AKR1C3 siRNA) or Stealth™ RNAi Negative Control Duplexes (NTC). Data are presented as mean ± se of values from three independent experiments run and expressed as a percent of NTC basal. *, P < 0.05, compared with NTC basal level. C, The level of testosterone in the media with H295R cells treated for 48 h without (NTC) or with indomethacin (10 μm). Data are presented as mean ± se of values from three independent experiments run and expressed as a percentage of NTC. *, P < 0.05, compared with NTC level.

Steroid levels in human adrenal and iliac vein

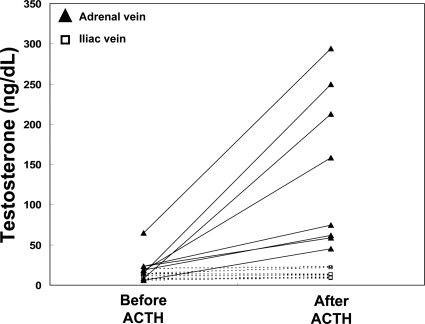

Adrenal testosterone production was examined in eight independent adrenal vein samples taken before and after ACTH administration (15 min). Testosterone levels in adrenal vein plasma increased by average 6.3-fold after ACTH administration (Fig. 5A and Table 1). The increase in testosterone production was not different in pre- or postmenopausal women (data not shown). The increase in testosterone did not result from peripheral conversion of adrenal androgen precursor, because there was no change in iliac vein plasma after 15 min ACTH administration (Fig. 5B and Table 1).

Figure 5.

Testosterone levels in the adrenal vein and iliac vein from women (n = 8) before and 15 min after iv ACTH administration (0.25 mg). As described in Materials and Methods, testosterone levels were measured using LC-MS-MS and values for both iliac vein (squares) and adrenal vein (triangles) are shown for each subject.

Table 1.

Plasma aldosterone, cortisol, and testosterone levels detected in the adrenal vein and iliac vein of women (n = 8) before and 15 min after iv ACTH administration (0.25 mg)

| Aldosterone (ng/dl) | Cortisol (ug/dl) | Testosterone (ng/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenal vein | |||

| Pre-ACTH | 60.3 | 22.3 | 18.5 |

| Post-ACTH | 1717.6 | 612.5 | 116.3 |

| Iliac vein | |||

| Pre-ACTH | 7.9 | 5.7 | 24.1 |

| Post-ACTH | 19.4 | 15.1 | 30.1 |

Testosterone and cortisol were measured using LC-MS-MS, and aldosterone was measured using RIA. Each value is shown as the median.

Discussion

In this study, we used microarray analysis to compare the expression of steroidogenic enzymes between the human adrenal ZF and ZR. As was previously demonstrated, HSD3B2, steroid sulfotransferase (SULT2A1), and CYB5 are differentially expressed between the zones in a manner that supports the production of cortisol by the ZF and DHEA-sulfate by the ZR (1). However, this analysis also demonstrated that AKR1C3 was predominantly expressed in the ZR in the human adult adrenal gland. The ability of this enzyme to convert androstenedione to testosterone provides a potential mechanism for adrenal production of testosterone in normal physiology and in diseases associated with androgen excess.

There are several enzymes that are currently known to have the ability to catalyze the conversion of androstenedione to testosterone, specifically HSD17B1, AKR1C3, HSD17B3, AKR1C1, AKR1C2, and AKR1C4 (2,9,16). Within the testis, the enzyme HSD17B3 is localized to the Leydig cells, where it actively synthesizes testosterone from androstenedione (2,12,23). This enzyme is not found in the ovary or the adrenal, leaving the method for ovarian and adrenal testosterone synthesis open. The ovary expresses both HSD17B1 and AKR1C3, giving this tissue two enzymes that could be involved in testosterone biosynthesis. A number of peripheral nonendocrine tissues have been shown to express high levels of AKR1C3, and it is this enzyme in muscle that is now believed to use circulating androstenedione to locally produce testosterone (24). Herein, we demonstrated that the expression levels of HSD17B1 and HSD17B3 mRNA were very low in the adrenal gland when compared with ovary or testis, respectively. In addition, we also confirmed that these genes expression levels are much lower in H295R cells compared with AKR1C3 (data not show). However, it is true that these enzymes are important for testosterone production in human tissues, and further studies are needed to determine whether expression of very small amounts of these enzymes could contribute to testosterone production in human adrenal gland. Dufort and colleagues (25) reported that AKR1C3 protein is detectable in the human adrenal gland, liver, prostate, and prostate cancer cell line using Western analysis. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies regarding AKR1C3 localization in the human adrenal gland. Our results are intriguing in that they show that AKR1C3 mRNA and protein are predominantly expressed in ZR cells within the human adrenal gland. Pelletier et al. (26) previously reported that mice have an adrenal expression pattern of AKR1C3 that is restricted to the ZR of female adrenal gland but not in the male mouse adrenal gland. They also demonstrated that mouse AKR1C3 has some 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD) activity (26). They suggested that adrenal cells released metabolites of progesterone, which would be effectively inactivated by the female adrenal ZR 20α-HSD (26). This does not appear to be the case in human adrenal gland because the levels of 20α-hydroxyprogesterone are very low in adrenal vein (data not shown). In this study, we also compared the different expression levels of AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, and AKR1C4. We confirmed that AKR1C1 mRNA expression level was relatively high in the adrenal gland as shown in a previous report (27). However, in our study, inhibition of AKR1C1 mRNA expression by 70% did not repress testosterone production in H295R cells (data not shown). It is reported that testosterone conversion from androstenedione occurs much more efficiently via AKR1C3 than through AKR1C1 (9). Our microarray and qPCR data suggested that AKR1C2 and AKR1C4 mRNA levels were very low in the adrenal gland, which seems to be compatible with a previous report (27). Therefore, it can be postulated that AKR1C3 is more likely to contribute to more testosterone production in the ZR compared with AKR1C1, AKR1C2, or AKR1C4. However, it awaits further study to clarify the exact role of each aldo-keto reductase family member in adrenal testosterone production in the future.

Based on our findings, the expression and role of AKR1C3 appear to be different for human adrenals compared with mice. First, in humans, there is high expression of CYP17 in both the ZF and ZR (1). CYP17 acts to convert much of the progesterone produced within the adrenal to 17-hydroxy steroids including cortisol and decreases active progestin release from the adrenal gland. In addition, immunoreactivity and qPCR analysis for AKR1C3 suggests that its expression occurs in the ZR of adrenal gland from both men and women (data not shown). Moreover, our LC/MS analysis demonstrated that the amount of 20α-hydroxyprogesterone is much smaller than that of progesterone in the adrenal vein (data not shown). To better define the role of AKR1C3 in human adrenal cell steroid production, we made use of the H295R adrenal cell line. This cell line has characteristics of both the ZF and ZR adrenal zones, expresses AKR1C3, and also secretes testosterone (19,28). Depletion of AKR1C3 expression using siRNA led to a significant drop in H295R testosterone production, whereas no decrease was observed after decreases in AKR1C1. Using a pharmacological approach, we also showed that indomethacin, which has been shown to inhibit AKR1C3 activity, partially blocks adrenal cell testosterone production (19). These data support a role of AKR1C3 in human adrenal testosterone biosynthesis.

Although most research focuses on adrenal production of aldosterone, cortisol, and DHEA, the human adrenal gland produces a wide range of steroids and steroid precursors. There is considerable evidence that the adrenal contributes to the circulating levels of testosterone, particularly in women, where normal gonadal testosterone production is considerably less than that seen in men. In addition, there have been several reports that examined direct secretion of testosterone from the ovarian and adrenal veins (3,7,29,30,31,32,33). These studies focused on women with androgen excess and demonstrated that the majority of these women have higher levels of adrenal testosterone production. Parker et al. (31) and Greenblatt et al. (3) measured testosterone levels in the adrenal vein after iv administration of ACTH. In their studies, ACTH administration tended to increase testosterone levels in the female adrenal vein (3,31). Herein, we confirmed that ACTH significantly elevated testosterone levels in the female adrenal vein samples (6.3-fold compared with that before ACTH stimulation). In addition, there did not appear to be a significant difference in ACTH-stimulated adrenal testosterone production based on menopausal status; however, further studies with a larger patient population are needed to confirm our preliminary observation.

Quinkler et al. (34) reported that human adipose tissue plays an important role in production of active androgen through the activity of AKR1C3. Thus, the role of AKR1C3 in producing testosterone in extratesticular tissue appears clear. However, Goodarzi et al. (35) have also recently demonstrated that polymorphisms in the AKR1C3 gene are not associated with serum testosterone levels in women. Thus, currently, there does not appear to be a genetic component to link excess testosterone to AKR1C3. However, based on the current study, it is postulated that human adrenal AKR1C3 may well provide a mechanism for the adrenal to contribute to the circulating pool of testosterone in women.

In summary, we have confirmed that testosterone is directly secreted from the human adrenal under the control of ACTH. Of the primary enzymes previously shown to convert androstenedione to testosterone, AKR1C3 was found to be expressed in human adrenal gland. Within the adrenal gland, AKR1C3 expression was higher in the ZR than in the ZF. In vitro knockdown of AKR1C3 expression in adrenal cells decreased production of testosterone. These results indicate that the expression of AKR1C3 in the ZR plays a role in adrenal testosterone production.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK069950 to W.E.R. and AG12287 to P.J.H.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online March 31, 2009

Abbreviations: AKR1C3, Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3; AVS, adrenal vein sampling; CYB5, cytochrome b5; CV, coefficient of variation; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; HSD17B3, type 3 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; LC-MS-MS, liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry; LLQ, limit of quantification; qPCR, quantitative real-time RT-PCR; T-d5, testosterone-2,2,4,6,6-d5; ZF, zona fasciculata; ZR, zona reticularis.

References

- Rainey WE, Nakamura Y 2008 Regulation of the adrenal androgen biosynthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 108:281–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F, Luu-The V, Belanger A, Lin SX, Simard J, Pelletier G, Labrie C 2005 Is dehydroepiandrosterone a hormone? J Endocrinol 187:169–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt RB, Colle ML, Mahesh VB 1976 Ovarian and adrenal steroid production in the postmenopausal woman. Obstet Gynecol 47:383–387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granoff AB, Abraham GE 1979 Peripheral and adrenal venous levels of steroids in a patient with virilizing adrenal adenoma. Obstet Gynecol 53:111–115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon U, Clarke D, McKenna TJ, Cunningham SK 1998 Intra-adrenal factors are not involved in the differential control of cortisol and adrenal androgens in human adrenals. Eur J Endocrinol 138:567–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham GE, Chakmakjian ZH, Buster JE, Marshall JR 1975 Ovarian and adrenal contributions to peripheral androgens in hirsute women. Obstet Gynecol 46:169–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl NL, Teeslink CR, Greenblatt RB 1973 Ovarian, adrenal, and peripheral testosterone levels in the polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 117:194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning TM, Steckelbroeck S, Bauman DR, Miller MW, Jin Y, Peehl DM, Fung KM, Lin HK 2006 Aldo-keto reductase (AKR) 1C3: role in prostate disease and the development of specific inhibitors. Mol Cell Endocrinol 248:182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning TM, Burczynski ME, Jez JM, Hung CF, Lin HK, Ma H, Moore M, Palackal N, Ratnam K 2000 Human 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms (AKR1C1-AKR1C4) of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily: functional plasticity and tissue distribution reveals roles in the inactivation and formation of male and female sex hormones. Biochem J 351:67–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP 2006 Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2006 66:2815–2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura K, Shiraishi H, Hara A, Sato K, Deyashiki Y, Ninomiya M, Sakai S 1998 Identification of a principal mRNA species for human 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoform (AKR1C3) that exhibits high prostaglandin D2 11-ketoreductase activity. J Biochem 124:940–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Aoki S, Xing Y, Sasano H, Rainey WE 2007 Metastin stimulates aldosterone synthesis in human adrenal cells. Reprod Sci 14:836–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yang L, Suwa T, Casson PR, Hornsby PJ 2001 Differentially expressed genes in zona reticularis cells of the human adrenal cortex. Mol Cell Endocrinol 173:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman KS, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2003 Profiling the steroidogenic pathway in human fetal and adult adrenals. J Soc Gynecol Investig 10:372–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirianni R, Rehman KS, Carr BR, Parker Jr CR, Rainey WE 2005 Corticotropin-releasing hormone directly stimulates cortisol and the cortisol biosynthetic pathway in human fetal adrenal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SX, Shi R, Qiu W, Azzi A, Zhu DW, Dabbagh HA, Zhou M 2006 Structural basis of the multispecificity demonstrated by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase types 1 and 5. Mol Cell Endocrinol 248:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP 2006 Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res 66:2815–2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HK, Steckelbroeck S, Fung KM, Jones AN, Penning TM 2004 Characterization of a monoclonal antibody for human aldo-keto reductase AKR1C3 (type 2 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase): immunohistochemical detection in breast and prostate. Steroids 69:795–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman DR, Rudnick SI, Szewczuk LM, Jin Y, Gopishetty S, Penning TM 2005 Development of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug analogs and steroid carboxylates selective for human aldo-keto reductase isoforms: potential antineoplastic agents that work independently of cyclooxygenase isozymes. Mol Pharmacol 67:60–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh F, Abe T, Tanemoto M, Nakamura M, Abe M, Uruno A, Morimoto R, Sato A, Takase K, Ishidoya S, Arai Y, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Ishibashi T, Ito S 2007 Localization of aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenomas: significance of adrenal venous sampling. Hypertens Res 30:1083–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MH, Mayhew B, Rehman K, White PC, Mantero F, Arnaldi G, Stewart PM, Bujalska I, Rainey WE 2005 Expression profiles for steroidogenic enzymes in adrenocortical disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5446–5455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdar AF, Oie HK, Shackleton CH, Chen TR, Triche TJ, Myers CE, Chrousos GP, Brennan MF, Stein CA, La Rocca RV 1990 Establishment and characterization of a human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line that expresses multiple pathways of steroid biosynthesis. Cancer Res 50:5488–5496 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler WM, Davis DL, Wu L, Bradshaw KD, Patel S, Mendonca BB, Elliston KO, Wilson JD, Russell DW, Andersson S 1994 Male pseudohermaphroditism caused by mutations of testicular 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3. Nat Genet 7:34–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Zhou M, Labrie F, Lin SX 2004 Crystal structures of the multispecific 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5: critical androgen regulation in human peripheral tissues. Mol Endocrinol 18:1798–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufort I, Rheault P, Huang XF, Soucy P, Luu-The V 1999 Characteristics of a highly labile human type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Endocrinology 140:568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier G, Luu-The V, Li S, Labrie F 2005 Localization of type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase mRNA in mouse tissues as studied by in situ hybridization. Cell Tissue Res 320:393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa M, Nakajima T, Yasuda K, Kanzaki H, Sasaguri Y, Watanabe K, Ito S 2000 Close kinship of human 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene with three aldo-keto reductase genes. Genes Cells 5:111–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey WE, Bird IM, Mason JI 1994 The NCI-H295 cell line: a pluripotent model for human adrenocortical studies. Mol Cell Endocrinol 100:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham GE 1975 Ovarian and adrenal contribution to peripheral steroids during the menstrual cycle in two hirsute women. Obstet Gynecol 46:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RJ, Abraham GE 1975 Peripheral arterial and venous concentrations of various androgens in patients with and without hirsutism. Obstet Gynecol 46:549–550 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker Jr CR, Bruneteau DW, Greenblatt RB, Mahesh VB 1975 Peripheral, ovarian, and adrenal vein steroids in hirsute women: acute effects of human chorionic gonadotropin and adrenocorticotrophic hormone. Fertil Steril 26:877–888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner MA, Jacobs JB 1971 Combined ovarian and adrenal vein catheterization to determine the site(s) of androgen overproduction in hirsute women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 33:199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl NL, Teeslink CR, Beauchamps G, Greenblatt RB 1973 Serum testosterone levels in hirsute women: a comparison of adrenal, ovarian, and peripheral vein values. Obstet Gynecol 41:650–654 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinkler M, Sinha B, Tomlinson JW, Bujalska IJ, Stewart PM, Arlt W 2004 Androgen generation in adipose tissue in women with simple obesity: a site-specific role for 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5. J Endocrinol 183:331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi MO, Jones MR, Antoine HJ, Pall M, Chen YD, Azziz R 2008 Nonreplication of the type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene association with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:300–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]