Abstract

Context: Abdominal adiposity is associated with reduced spontaneous GH secretion, and an increased incidence of the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Exercise training increases GH secretion, induces abdominal visceral fat loss, and has been shown to improve the cardiometabolic risk factor profile. However, little is known about the effects of endurance training intensity on spontaneous GH release in obese individuals.

Objective: Our objective was to examine the effects of 16 wk endurance training on spontaneous 12-h overnight GH secretion in adults with the metabolic syndrome.

Design and Setting: This randomized, controlled exercise intervention was conducted at the University of Virginia.

Participants: A total of 34 adults with the metabolic syndrome (mean ± sem: age: 49.1 ± 1.8 yr) participated.

Intervention: Participants were randomized to one of three groups for 16 wk: no exercise training (control), low-intensity exercise training, or high-intensity training.

Main Outcome Measure: Change in nocturnal integrated GH area under the curve (AUC) was calculated.

Results: Both exercise training conditions augmented within-group nocturnal GH AUC pretrain to post-training (low-intensity exercise training approximately ↑49%, P < 0.05; and high-intensity training approximately ↑65%, P < 0.01), and these changes were also greater than the changes in the control group (P < 0.01). The change in nocturnal GH AUC was inversely associated with the change in fat mass across the entire sample (r = −0.34; P = 0.051; n=34) but was not significantly associated with the change in abdominal visceral fat (r = 0.02; P = 0.920; n = 34).

Conclusions: Sixteen wk of supervised exercise training in adults with the metabolic syndrome increases spontaneous nocturnal GH secretion independent of exercise training intensity.

Sixteen weeks of supervised exercise training in adults with the metabolic syndrome increases spontaneous nocturnal GH secretion independent of exercise training intensity.

Abdominal adiposity is associated with reduced spontaneous GH secretion and increased cardiometabolic risk, including elevated biomarkers of inflammation, and increased incidence of the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (1,2,3,4). One year of GH administration reduced abdominal visceral fat (AVF) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in abdominally obese women (5), and C-reactive protein and IL-6 in abdominally obese postmenopausal women (4). GH also stimulates lipolysis and is influenced by AVF in non-GH-deficient adults (6).

Although GH treatment can reduce AVF and associated cardiometabolic risk, it has not gained widespread use for a variety of reasons, including side effects and cost. Exercise training is a safe and effective way to increase GH secretion, induce AVF loss, and has improved the cardiometabolic risk factor profile (7,8). Mechanistically, exercise-induced GH secretion may provide a physiologically important signal for the mobilization of AVF. We have reported that there is a linear-dose response relationship between acute exercise intensity and GH release across the full range of exercise intensities in both young and older adults (9,10), and have suggested that higher training intensity is associated with improved fitness and increased spontaneous 24-h GH release in normal weight women (11,12).

Obesity attenuates spontaneous GH secretion as well as the GH response to exercise (13,14,15). The decrease in spontaneous 24-h GH secretion in obesity has been attributed to a decrease in pulsatile GH release and a shorter half-life of endogenous GH (16). Although short-term endurance exercise had no effect on exercise-stimulated GH release in obese women (14), little is known about the effects of endurance training on spontaneous nocturnal GH release in obese individuals. In the present study, we examined the effects of 16 wk endurance training on spontaneous 12-h overnight GH secretion in obese adults with the metabolic syndrome. We chose to study nocturnal GH secretion because of logistical difficulties associated with 24 h sampling in this group of subjects and based on the fact that nocturnal GH secretion constitutes most (>85%) of the total daily GH output (17). We hypothesized that under equivalent caloric expenditure, training above the lactate threshold (LT) (high-intensity endurance training) would result in a greater nocturnal GH secretion than training below the LT (low-intensity endurance training).

Subjects and Methods

Participants

The University of Virginia’s Institutional Review Board approved this study, and each participant provided written informed consent. A total of 34 sedentary (≤2 d/wk structured exercise), middle aged (mean ± sem; 49 ± 2 yr) adults who met the International Diabetes Federation criteria for the metabolic syndrome (18) completed the present study. Participants were screened for eligibility in the University of Virginia’s General Clinical Research Center (GCRC).

Metabolic syndrome and medical screening

As described previously (19), after a 10- to 12-h fast, participants provided a detailed medical history and underwent a physical examination, which included an assessment of the five risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome as defined by the International Diabetes Federation (18). All participants were asked to refrain from caffeine, alcohol, and vigorous physical activity for 24 h before testing. Participants with a history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, pulmonary or musculoskeletal limitations to exercise, and uncontrolled hypertension were excluded. Participants using vasoactive medications, oral hypoglycemics, insulin, glucocorticoids, hormone replacement or birth control, or were unwilling to provide written informed consent were also excluded.

Cardiorespiratory fitness assessment

A continuous incremental treadmill protocol was completed to determine each participant’s peak oxygen uptake (VO2 Peak) and LT (19). Ratings of perceived exertion (RPEs) were also obtained at the end of each stage.

GCRC admission

Eligible participants were admitted to the GCRC before and within 72 h after the last exercise session under identical conditions for 2 d during which the evaluations for body composition and blood sampling were performed (19). To control for the effects of menstrual cycle on outcome variables, premenopausal women (n = 11) were admitted between d 2 and 8 of their menstrual cycle. Participants were asked to refrain from vigorous physical activity, alcohol, caffeine, and cigarette smoking before their admission.

Body composition assessment

Body composition was assessed by air displacement plethysmography (Bod-Pod; Life Measurement Instruments, Concord, CA) corrected for thoracic gas volume (19,20). Abdominal sc, visceral, and total fat cross-sectional area measurements were acquired using single-slice computed tomography images obtained at the level of L4–L5 intervertebral disc space, as described previously (19,21,22). A single trained investigator analyzed each of the computed tomography images using the Slice-O-Matic version 4.3 software package (Tomovision, Montreal, Canada) (21,22).

Blood sampling procedures

Participants ingested a standardized meal at 1800 h, which was comprised of one third of their daily energy requirements as determined by the Harris-Benedict Equation (23), with a macronutrient composition of 55% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 30% fat. Beginning at 2000 h, blood samples were drawn every 10 min for 12 h, and every 60 min for 12 h for determination of serum GH and IGF-I concentrations, respectively. The serum samples were stored at −20 C until subsequent analysis in the GCRC Core Laboratory.

GH and IGF-I immunoassays

Serum GH and IGF-I concentrations were measured in duplicate by commercially available ultrasensitive chemiluminescent immunometric assays (Immulite 2000; Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA); the assay sensitivities were 0.05 and 20 μg/liter, respectively, and the mean intraassay coefficients of variation were 2.7 and 3.8%, respectively.

Deconvolution analysis

Automated multiparameter deconvolution analysis (24) was performed to analyze the GH pulsatile attributes using Pulse_XP (http://mljohnson.pharm.virginia.edu/home.html). Pulse_XP uses an automated algorithm, which iteratively estimates attributes of GH secretory events from serial measures of GH (25). As part of this automated analysis, data were initially analyzed using Pulse2, an algorithm that provides the best fit values for the weighted nonlinear least-squares parameter estimation of a number of parameters. These GH secretory estimates are then inserted into the initial deconvolution algorithm.

Exercise intervention

Participants were randomized to the one of the following three interventions: 1) no exercise training (control), 2) low-intensity exercise training (LIET), or 3) high-intensity training (HIET).

Control

Participants maintained their current level of physical activity for the duration of the study.

LIET

Participants completed a 16-wk supervised low-intensity exercise intervention. Participants were progressed to complete five exercise sessions (days) per week by wk 5 at an intensity at or below their LT (RPE ∼10–12). The duration of each exercise session was adjusted based on each participant’s individual oxygen uptake-velocity relationship so that each participant expended 300 kcal/training session for wk 1–2 (3 d/wk), 350 kcal/session for wk 3–4 (4 d/wk), and 400 kcal/session for wk 5–16 (5 d/wk). As each participant’s fitness level improved, the velocity required to maintain his/her assigned RPE was increased, therefore, the duration was readjusted to maintain the kilocalorie requirement. Exercise was prescribed based on the RPE obtained during the LT/VO2 Peak protocol, and one of the investigators monitored the RPE during each training session.

HIET

Participants completed a 16-wk supervised moderate-high intensity exercise intervention. Participants were progressed to five exercise sessions (days) per week by wk 5. Three days per week, participants exercised at an intensity midway between the LT and VO2 Peak (RPE ∼15–17), and the remaining 2 d, they exercised at or below their LT (RPE ∼10–12). The progression of caloric expenditures and the velocity and duration adjustments were made as described for LIET, with the exception that participants always had 3 d/wk at an exercise intensity greater than the LT and one training session at an intensity below the LT was added at wk 3 and again at wk 5.

The present study was part of a larger study examining the effect of exercise training intensity on AVF in adults with the metabolic syndrome [preliminary body composition data on the women have recently been reported (19)]. A total of 108 volunteers were screened for the presence of the metabolic syndrome; 51 participants met the metabolic syndrome inclusion criteria. Three of these participants were excluded because of incomplete GH data; one participant was excluded for having a significantly abnormal GH profile. The remaining 47 participants were randomized to one of the three treatment conditions. In total, six females and four males completed the control condition, 10 females and three males completed the LIET condition, and eight females and three males completed the HIET condition. There were three dropouts in the control condition and five dropouts each in two exercise-training conditions.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). As stated previously, the present study was part of a larger study examining the effect of exercise training intensity on AVF in adults with the metabolic syndrome and was powered to detect an approximate 30-cm2 reduction in AVF with 12 participants per group. Data were analyzed using mixed-effects analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models, in which the model parameters were specified in a factorial treatment design, with exercise intensity serving as the factor, and control, LIET, and HIET as the factor levels. In addition, each participant’s baseline value and gender were used as covariates. The GH and IGF-I data were log transformed for analysis, as a variance stabilizing transformation to reduce heterogeneous variance and as a remedial measure to reduce the impact that single extreme observations had on the statistical analysis (26). Finally, we conducted correlation analyses between the change in 12-h GH area under the curve (AUC) and the change in AVF to determine whether there was an association between the change in 12-h GH AUC and the change in AVF.

Results

Exercise adherence

Both the LIET and HIET groups had similar exercise adherence (P > 0.10), with approximately 76 ± 3% (21,736 ± 858 kcal) and approximately 83 ± 3% (23,738 ± 858 kcal) of the assigned exercise sessions completed within each exercise condition, respectively. During LIET exercise sessions, the mean RPE was approximately 11; for HIET, the RPE was approximately 15 during the high-intensity exercise sessions and approximately 12 during the low-intensity exercise sessions.

Metabolic syndrome parameters (Table 1)

Table 1.

The metabolic syndrome parameters obtained at the pretraining and post-training assessments, in response to 16 wk of either no exercise training (control), LIET, or HIET

| Control (6 F, 4 M)

|

LIET (10 F, 3 M)

|

HIET (8 F, 3 M)

|

ANCOVA (treat, time, treat*time) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Post-training | Pretraining | Post-training | Pretraining | Post-training | ||

| Waist circumference (cm2) | 103.5 ± 3.6 | 100.9 ± 2.8 | 108.2 ± 3.8 | 106.2 ± 3.8 | 106.5 ± 5.7 | 101.6 ± 5.2a | (0.213, <0.001, 0.325) |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) | 107.0 ± 3.9 | 110.0 ± 4.7 | 107.0 ± 3.5 | 106.2 ± 3.1 | 110.0 ± 5.7 | 111.7 ± 7.3 | (0.688, 0.566, 0.723) |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 42.2 ± 2.5 | 45.6 ± 3.5 | 42.1 ± 2.3 | 45.9 ± 3.2 | 48.5 ± 3.6 | 51.1 ± 3.4 | (0.989, 0.010, 0.933) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 200.8 ± 28.0 | 229.7 ± 40.1 | 253.2 ± 50.4 | 242.8 ± 42.7 | 140.8 ± 19.1 | 122.1 ± 19.1 | (0.304, 0.706, 0.329) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 129 ± 3 | 130 ± 3 | 135 ± 4 | 124 ± 3a,b,c | 122 ± 5 | 122 ± 4 | (0.149, 0.078, 0.034) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 75 ± 2 | 77 ± 2 | 81 ± 3 | 78 ± 3 | 75 ± 2 | 75 ± 2 | (0.762, 0.890, 0.300) |

Data are presented as mean ± sem. Mixed-effects ANCOVA with repeated measures was used to test the main effects of exercise intensity and time on the dependent variables adjusted for each participant’s baseline value and sex (see Subjects and Methods for details). To convert values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551. To convert values for high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259. To convert values for triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.01129. F, Females; M, males.

Significant within-group treatment effect (P < 0.01).

Significant between-group treatment effect compared with control (P < 0.05).

Significant between-group treatment effect compared with HIET (P < 0.05).

HIET significantly reduced waist circumference (P = 0.002). LIET significantly reduced systolic blood pressure (P < 0.001). The reduction in systolic blood pressure in the LIET condition was significantly greater than that observed in both the control and HIET conditions (P = 0.021 and P = 0.033, respectively). The control condition had no significant affect on any of the metabolic syndrome parameters.

Cardiorespiratory fitness (Table 2)

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2 Peak) and body composition measurements obtained at the pretraining and post-training assessments, in response to 16 wk of either no exercise training (control), LIET, or HIET

| Control (6 F, 4 M)

|

LIET (10 F, 3 M)

|

HIET (8 F, 3 M)

|

ANCOVA (treat, time, treat*time) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Post-training | Pretraining | Post-training | Pretraining | Post-training | ||

| Age (yr) | 49.2 ± 4.8 | 49.2 ± 1.8 | 49.0 ± 2.9 | ||||

| Height (cm) | 173.1 ± 3.7 | 169.0 ± 7.4 | 168.5 ± 8.3 | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 95.9 ± 4.4 | 93.5 ± 3.7 | 101.7 ± 6.6 | 99.0 ± 5.7a | 97.7 ± 6.6 | 95.0 ± 6.5a | (0.941, <0.001, 0.974) |

| VO2 Peak (ml/kg/min) | 24.7 ± 1.9 | 25.7 ± 2.5 | 22.0 ± 1.0 | 23.6 ± 0.8 | 22.7 ± 1.4 | 25.9 ± 1.7b | (0.351, 0.004, 0.344) |

| Peak treadmill velocity (m/min) | 127 ± 8 | 133 ± 10 | 116 ± 4 | 124 ± 4 | 119 ± 5a | 138 ± 8b,c | (0.024, <0.001, 0.034) |

| Fat (%) | 41.2 ± 1.7 | 40.0 ± 2.4 | 42.9 ± 1.7 | 42.2 ± 1.5a | 41.2 ± 1.7 | 39.6 ± 1.7a | (0.581, 0.005, 0.635) |

| BMI (kg/m) | 32.0 ± 1.1 | 31.3 ± 1.1 | 35.5 ± 2.2 | 34.6 ± 1.9a | 34.2 ± 1.8 | 33.3 ± 1.8a | (0.936, <0.001, 0.895) |

| Abdominal fat (cm2) | 638 ± 28 | 600 ± 28b | 687 ± 52 | 663 ± 49 | 683 ± 62 | 627 ± 61b | (0.189, <0.001, 0.188) |

| Subcutaneous fat (cm2) | 463 ± 24 | 438 ± 25a | 509 ± 52 | 490 ± 50 | 502 ± 52 | 457 ± 50b | (0.148, <0.001, 0.156) |

| Visceral fat (cm2) | 163 ± 21 | 153 ± 19 | 168 ± 13 | 157 ± 11 | 176 ± 21 | 164 ± 20 | (0.995, 0.022, 0.593) |

Data are presented as mean ± sem. Mixed-effects ANCOVA with repeated measures was used to test the main effects of exercise intensity and time on the dependent variables adjusted for each participant’s baseline value and sex (see Subjects and Methods for details). F, Females; M, males.

Significant within-group treatment effect (P < 0.05).

Significant within-group treatment effect (P < 0.01).

Significant between-group treatment effect compared with control (P < 0.01).

There was a significant exercise-induced elevation in VO2 Peak after the HIET (P = 0.006) condition. Peak treadmill velocities increased in both the LIET (P = 0.015) and HIET (P < 0.001) conditions. The control condition did not significantly affect either VO2 Peak or peak treadmill velocity. The elevation in peak treadmill velocity in response to HIET was greater than both the control (P = 0.016) and LIET (P = 0.035) conditions.

Body composition (Table 2)

HIET significantly reduced total body weight (P = 0.024), body mass index (BMI) (P = 0.020), and fat mass (P = 0.015). LIET significantly reduced total body weight (P = 0.015), BMI (P = 0.016), and fat mass (P = 0.034). HIET significantly reduced total abdominal fat (P < 0.001) and abdominal sc fat (P = 0.034) cross-sectional areas. LIET significantly reduced total abdominal fat (P = 0.046) cross-sectional area. The total abdominal fat and abdominal sc fat cross-sectional areas were also reduced in the control condition (P = 0.007 and P = 0.029, respectively). Because there were no significant differences between the LIET and HIET conditions (in this mixed gender analysis) with respect to changes in body composition, we pooled the two exercise training conditions (n = 24) to examine the impact of exercise training independent of training intensity on changes in body composition. Pooling the two exercise training groups revealed significant within-group reductions in total abdominal fat (P < 0.001), abdominal sc fat (P < 0.001), and AVF (P = 0.037) cross-sectional areas.

Nocturnal GH and IGF-I secretory parameters (Table 3 and Fig. 1)

Table 3.

The effects of 16 wk no exercise training (control), LIET, or HIET on GH secretory parameters and IGF-I

| Control (6 F, 4 M)

|

LIET (10 F, 3 M)

|

HIET (8 F, 3 M)

|

ANCOVA (treat, time, treat*time) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Post-training | Pretraining | Post-training | Pretraining | Post-training | ||

| GH basal secretion (μg/liter) | 0.002 ± 0.0002 | 0.002 ± 0.0005 | 0.002 ± 0.0003 | 0.002 ± 0.0004 | 0.002 ± 0.0005 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | (0.486, 0.062, 0.555) |

| GH secretory pulses/12 h | 10.8 ± 1.1 | 9.6 ± 0.8 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | (0.611, 0.656, 0.806) |

| GH half-life (min) | 16.5 ± 1.0 | 15.3 ± 0.8 | 15.1 ± 0.8 | 13.7 ± 0.8 | 16.2 ± 1.1 | 16.1 ± 1.0 | (0.303, 0.189, 0.664) |

| GH interpulse interval (min) | 64.7 ± 6.8 | 69.3 ± 5.0 | 70.9 ± 2.8 | 82.5 ± 11.3 | 92.2 ± 18.8 | 73.1 ± 5.6 | (0.520, 0.894, 0.405) |

| GH mass per pulse (μg/liter) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.4a,b | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.6a,b | (0.098, 0.059, 0.037) |

| GH pulse amplitude (μl/liter) | 0.089 ± 0.022 | 0.081 ± 0.034 | 0.047 ± 0.007 | 0.069 ± 0.010a,b | 0.064 ± 0.018 | 0.087 ± 0.021a,c | (0.167, 0.122, 0.013) |

| GH production rate (μg/liter per 12 h) | 15.5 ± 2.1 | 11.2 ± 2.0 | 8.9 ± 1.6 | 16.2 ± 3.5a,b | 16.1 ± 4.9 | 21.6 ± 8.1a,b | (0.126, 0.101, 0.020) |

| GH AUC (μg/liter · 12 h) | 414 ± 58 | 273 ± 34 | 235 ± 47 | 370 ± 79a,c | 397 ± 104 | 509 ± 114a,c | (0.030, 0.154, 0.006) |

| IGF-I (ng/ml) | 141 ± 17 | 121 ± 17 | 100 ± 10 | 106 ± 11 | 134 ± 11 | 129 ± 10 | (0.328, 0.354, 0.081) |

Data are presented as mean ± sem. The data were log transformed for analysis. Mixed-effects ANCOVA with repeated measures models was used to test the main effects of exercise intensity and time on the dependent variables adjusted for each participant’s baseline value and sex (see Subjects and Methods for details). To convert values for IGF-I to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 0.131. F, Females; M, males.

Significant within-group treatment effect (P < 0.05).

Significant between-group treatment effect compared with control (P < 0.05).

Significant between-group treatment effect compared with HIET (P < 0.05).

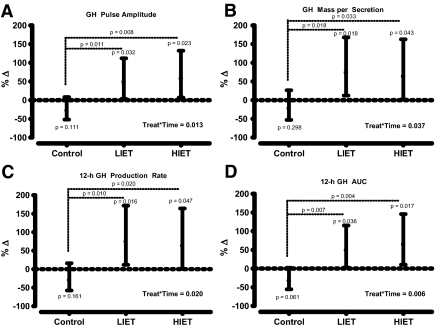

Figure 1.

Percent change (%Δ) [(ratio of the geometric mean − 1)100] in GH pulse amplitude (A), mass per secretion (B), 12-h production rate (C), and integrated AUC (D) in response to 16 wk no exercise training (control), LIET, or HIET. The values are the least square means in the percent change (solid dot) adjusted for each participant’s baseline value and gender, and least significant difference 95% confidence intervals (solid line). Mixed-effects ANCOVA with repeated measures models was used to test the main effects of exercise intensity and time on the dependent variables. The model specification included parameters to estimate the exercise intensity main effect (control, LIET, HIET), time main effect (pretraining, post-training), and their interaction effect on the change in the dependent variables. In addition, each participant’s baseline values and gender were used as covariates. For all analyses, linear contrasts of the means were constructed to test our a priori hypotheses. Fisher’s least significant differences criterion was used to maintain the a priori type I error rate at 0.05.

No differences were observed within or among groups before or after the intervention for GH basal secretion, secretory pulse frequency, or half-life. Both exercise training conditions resulted in within-group elevations in GH pulse amplitude [LIET approximately ↑50%, P < 0.05 and HIET approximately ↑60%, P < 0.05)], mass secreted per pulse [LIET approximately ↑75%, P < 0.05 and HIET approximately ↑65%, P < 0.05)], 12-h production rate [LIET approximately ↑75%, P < 0.05 and HIET approximately ↑63%, P < 0.05)], and GH AUC [LIET approximately ↑49%, P < 0.05 and HIET approximately ↑65%, P < 0.05)]. All of these augmentations in GH secretion were significantly greater than the changes observed within the control group (all P < 0.05 for between group comparisons). No significant within or between-group differences in IGF-I concentrations were observed before to after training.

Correlation analysis

There was no significant association between the change in AVF and the change in 12-h GH AUC across the entire sample (r = 0.02; P = 0.920; n = 34). The change in fat mass was inversely associated with the change in 12-h GH AUC across the entire sample (r = −0.34; P = 0.051; n = 34).

Discussion

Spontaneous pulsatile GH release and GH secretion to various exogenous stimuli are markedly attenuated in obese individuals, and are thought to be mediated in part by elevated abdominal fat. The primary findings of the present study indicate that 16 wk supervised exercise training increases nocturnal GH release and decreases abdominal fat in abdominally obese adults with the metabolic syndrome. There were 12-h overnight GH profiles with 10-min sampling periods used to examine GH secretion (13), and similar to previous findings, indicate that the augmentation in nocturnal GH secretion was related to an increase in mass of GH secreted per pulse because exercise training did not affect GH pulse frequency or GH half-life.

The present data support our original hypothesis that exercise training would increase nocturnal GH secretion but require us to reject our hypothesis that HIET would augment spontaneous GH secretion. We based our hypotheses on previous findings from our laboratory that indicate that 1 yr exercise training resulted in a training intensity dependent response in spontaneous GH secretion in young women (20). It is possible that the lack of a training intensity effect on GH secretion was due to the shorter duration of the present study (16 wk vs. 1 yr). For example, in relatively unfit individuals (such as the present subjects), the initiation of a chronic exercise program may be enough to stimulate an adaptation in spontaneous GH secretion independent of training intensity (Table 3). After this initial adaptation occurs, further improvements in GH secretion may be intensity dependent. For GH secretory parameters, greater increases over time were observed at 1 yr in the HIET group compared with the moderate-intensity training group (12). In support of this notion, in our previous work in nonobese women, we showed improvement in fitness outcome measures at approximately 16 wk that were independent of training intensity, whereas by the end of 1 yr, significant training intensity dependent differences were present (11).

Deconvolution analysis was used to examine GH secretion profiles (24,25). Exercise (of increasing intensity or duration) is associated with an increase in the amount of GH secreted per burst rather than in the number of bursts (9,10,27,28). This likely explains the increase observed in 24-h GH AUC in acute exercise conditions (28) because mechanistically pulsatile secretion constitutes most (>85%) of the total daily GH output (17). The present data are consistent with our previous findings in young women in that the increase in nocturnal GH release was related to an increase in the mass of GH secreted per pulse (12). As we reviewed previously, this training-induced alteration in GH secretion may be important to target tissues.

It is not surprising that the increase in GH secretion as a result of exercise training was accompanied by a reduction in abdominal fat (both abdominal sc fat and AVF). However, in the present investigation, we did not observe a significant association between the reduction in AVF and the increase in 12-h GH AUC. However, most subjects lost a significant amount of visceral fat, although the exercise-trained participants remained viscerally obese (e.g. AVF > 130 cm2). Therefore, the low correlation may be due to similar reductions in AVF and a clustering of data points. We also previously reported (see Fig. 2 from Ref. 29) that there is a weak association between 24-h GH secretion and AVF, when the AVF values are greater then 130 cm2. In addition, it is possible that sleep quality may have improved and interacted with the reduction in AVF to stimulate nocturnal GH release.

Disturbed and/or low-quality sleep is often reported by abdominally obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome (30). Sleep apnea, which is more common among obese adults, may potentially contribute the reduced sleep quality that is often reported among obese adults. Impairments in sleep quality may be one mechanism by which obesity attenuates nocturnal GH secretion. For example, reductions in slow-wave (deep) sleep have been associated with reductions in nocturnal GH secretion (31). Therefore, one could postulate that the reductions in slow-wave sleep (i.e. low quality sleep) that is often observed among abdominally obese adults with the metabolic syndrome plays an important role in attenuating nocturnal GH secretion. Exercise training has improved sleep quality (32). Although we did not examine the effects of exercise training-induced changes in sleep quality (or sleep apnea) on GH secretion in the present study, it seems plausible that exercise-induced improvements in sleep quality could have contributed to the improvements in nocturnal GH secretion that were observed in the present study. Finally, it is possible that exercise training affected other control mechanisms related to GH release (e.g. somatostatin withdrawal) or had an independent effect.

The present findings may have clinical implications. Data in abdominally obese adults reveal a relative hyposomatotropism (13,16) and similar cardiometabolic risk factors as observed in individuals with GH deficiency (33). Recent data suggest that attenuated GH secretion may be associated with sarcopenic obesity (34). The health outcomes of this condition have recently been elucidated (35). In non-GH-deficient adults, 1 yr GH treatment lowers AVF and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (5), and reduces inflammation (4). Although not examined in the present study, based on the elevation in nocturnal GH and the reduction in abdominal fat seen within 16 wk, it is possible that more prolonged exercise training (e.g. 1 yr) would result in additional increases in spontaneous GH secretion, reductions in visceral fat, and amelioration of associated risk factors. Whether this is as effective as GH administration requires additional investigation. Alternatively, it is possible that the combination of exercise training and GH treatment may have an additive or supra-additive effect, or that exercise training might allow for a reduction in GH dosing in abdominal obesity, resulting in a lower risk of GH-associated side effects.

Despite significant improvements in body composition and elevations in GH secretion, the improvements in some of the cardiometabolic risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome did not reach statistical significance. However, LIET resulted in a significantly greater reduction in systolic blood pressure compared with the changes observed in the control and HIET conditions. Although this is consistent with a previous report that indicated that LIET is more effective than moderate-intensity exercise training for reducing blood pressure in mildly hypertensive adults (36), more recent data have been equivocal with regard to the effects of exercise intensity on postexercise hypotension and resting blood pressure. As such, it is likely that the significantly greater reduction in systolic blood pressure in the LIET condition was due in large part to the higher initial value in this group (37).

One limitation of the present study is that due to incomplete dietary data, we were not able to analyze adequately the impact of changes in dietary intake on GH secretion. Another potential limitation is the fact that a larger sample size may have been necessary to detect differences between the two exercise training conditions with respect to the GH secretory parameters. Although the present study was initially powered as part of a larger study to detect significant changes in the AVF (∼30 cm2) with 12 participants per group, we have reported significant within and between-group differences in exercise training-induced 24-h GH secretion with fewer than 10 participants per group after 1 yr endurance training in previously sedentary untrained women (12). A larger sample size likely would have resulted in narrower 95% confidence intervals but would have had less of an impact on the point estimates for the observed changes in the GH secretory parameters, which were fairly similar in magnitude between the two exercise training conditions.

In addition, exercise training did not influence IGF-I levels despite significant elevations in nocturnal GH secretion. This was not surprising because most of our exercise-trained participants lost weight, indicating that they were in an energy deficit during the study, which often results in a decrease in circulating IGF-I concentrations (38). Similarly, increased physical activity may also decrease circulating IGF-I concentrations (39). These data indicate that energy flux may be an important factor regulating the effect of short-term exercise on circulating IGF-I concentrations. Finally, the present data are consistent with previous findings that indicate that the addition of exercise training to a weight loss program abolished the reduction in circulating IGF-I concentrations typically observed with weight loss alone (40).

It should also be noted that there were modest changes observed in the control group. When individuals who volunteer for an exercise study are placed in the control condition, they often make modest lifestyle changes on their own. This could have reduced the magnitude of the differences observed between the control and exercise groups.

In summary, results of the present study indicate that 16 wk supervised exercise training, in abdominally obese adults with the metabolic syndrome, results in an elevation in spontaneous nocturnal GH secretion and favorable alterations in body composition. Whether a longer duration of exercise training (e.g. 1 yr) would result in differentiated exercise training intensity responses, and whether a combination of exercise training and GH treatment may be more effective than either intervention alone, require additional investigation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions and technical assistance of the staff of the General Clinical Research Center at the University of Virginia.

Footnotes

This publication was made possible by National Institutes of Health Grants RR00847 and T32-AT-00052.

Present address for B.A.I.: 200 First Street SW, Endocrine Research Unit, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota 55009.

Present address for C.K.D.: 3020 Children’s Way, MC 5004, Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California 92123.

Present address for D.W.B.: Rehabilitation and Movement Science, 310M Rowell Building, 106 Carrigan Drive, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405–0068.

Present address for G.A.G.: School of Applied Arts and Sciences, Arizona State University, 7350 E. Unity Avenue, Mesa, Arizona 85212.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 24, 2009

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, Analysis of covariance; AUC, area under the curve; AVF, abdominal visceral fat; BMI, body mass index; GCRC, General Clinical Research Center; HIET, high-intensity exercise training; LIET, low-intensity exercise training; LT, lactate threshold; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; VO2 Peak, peak oxygen uptake.

References

- Vahl N, Jorgensen JO, Skjaerbaek C, Veldhuis JD, Orskov H, Christiansen JS 1997 Abdominal adiposity rather than age and sex predicts mass and regularity of GH secretion in healthy adults. Am J Physiol 272(6 Pt 1):E1108–E1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchini FS, Hua N, Abbasi F, Reaven GM 2001 Insulin resistance as a predictor of age-related diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3574–3578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Brewer Jr HB, Cleeman JI, Smith Jr SC, Lenfant C 2004 Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 109:433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco C, Andersson B, Lonn L, Bengtsson BA, Svensson J, Johannsson G 2007 Growth hormone reduces inflammation in postmenopausal women with abdominal obesity: a 12-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2644–2647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco C, Brandberg J, Lonn L, Andersson B, Bengtsson BA, Johannsson G 2005 Growth hormone treatment reduces abdominal visceral fat in postmenopausal women with abdominal obesity: a 12-month placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1466–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasey JL, Weltman A, Patrie J, Weltman JY, Pezzoli S, Bouchard C, Thorner MO, Hartman ML 2001 Abdominal visceral fat and fasting insulin are important predictors of 24-hour GH release independent of age, gender, and other physiological factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3845–3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary VB, Marchetti CM, Krishnan RK, Stetzer BP, Gonzalez F, Kirwan JP 2006 Exercise-induced reversal of insulin resistance in obese elderly is associated with reduced visceral fat. J Appl Physiol 100:1584–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Fortier A, Hudson R, Ross R 2002 Effects of an energy-restrictive diet with or without exercise on abdominal fat, intermuscular fat, and metabolic risk factors in obese women. Diabetes Care 25:431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritzlaff CJ, Wideman L, Weltman JY, Abbott RD, Gutgesell ME, Hartman ML, Veldhuis JD, Weltman A 1999 Impact of acute exercise intensity on pulsatile growth hormone release in men. J Appl Physiol 87:498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritzlaff-Roy CJ, Widemen L, Weltman JY, Abbott R, Gutgesell M, Hartman ML, Veldhuis JD, Weltman A 2002 Gender governs the relationship between exercise intensity and growth hormone release in young adults. J Appl Physiol 92:2053–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltman A, Seip RL, Snead D, Weltman JY, Haskvitz EM, Evans WS, Veldhuis JD, Rogol AD 1992 Exercise training at and above the lactate threshold in previously untrained women. Int J Sports Med 13:257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltman A, Weltman JY, Schurrer R, Evans WS, Veldhuis JD, Rogol AD 1992 Endurance training amplifies the pulsatile release of growth hormone: effects of training intensity. J Appl Physiol 72:2188–2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Liem AY, South S, Weltman A, Weltman J, Clemmons DA, Abbott R, Mulligan T, Johnson ML, Pincus S 1995 Differential impact of age, sex steroid hormones, and obesity on basal versus pulsatile growth hormone secretion in men as assessed in an ultrasensitive chemiluminescence assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:3209–3222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaley JA, Weatherup-Dentes MM, Jaynes EB, Hartman ML 1999 Obesity attenuates the growth hormone response to exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3156–3161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prange Hansen A 1973 Serum growth hormone response to exercise in non-obese and obese normal subjects. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 31:175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Iranmanesh A, Ho KK, Waters MJ, Johnson ML, Lizarralde G 1991 Dual defects in pulsatile growth hormone secretion and clearance subserve the hyposomatotropism of obesity in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Weltman JY, Weltman AL, Iranmanesh A, Muller EE, Bowers CY 2004 Age and secretagogue type jointly determine dynamic growth hormone responses to exogenous insulin-like growth factor-negative feedback in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5542–5548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J 2006 Metabolic syndrome—a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med 23:469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving BA, Davis CK, Brock DW, Weltman JY, Swift D, Barrett EJ, Gaesser GA, Weltman A 2008 Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:1863–1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster P, Aitkens S 1995 A new air displacement method for the determination of human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc 27:1692–1697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving BA, Weltman JY, Brock DW, Davis CK, Gaesser GA, Weltman A 2007 NIH ImageJ and Slice-O-Matic computed tomography imaging software to quantify soft tissue. Obesity 15:370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lyons W, Gallagher D, Ross R 1998 Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol 85:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Benedict FG 1919 A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Carlson ML, Johnson ML 1987 The pituitary gland secretes in bursts: appraising the nature of glandular secretory impulses by simultaneous multiple-parameter deconvolution of plasma hormone concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:7686–7690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML, Pipes L, Veldhuis PP, Farhy LS, Boyd DG, Evans WS 2008 AutoDecon, a deconvolution algorithm for identification and characterization of luteinizing hormone secretory bursts: description and validation using synthetic data. Anal Biochem 381:8–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving BA, Patrie JT, Anderson SM, Watson-Winfield DD, Frick KI, Evans WS, Veldhuis JD, Weltman A 2004 The effects of time following acute growth hormone administration on metabolic and power output measures during acute exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4298–4305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wideman L, Consitt LA, Patrie J, Swearingin B, Bloomer R, Davis PG, Weltman A 2006 The impact of sex and exercise duration on growth hormone secretion. J Appl Physiol 101:1641–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltman A, Weltman JY, Watson Winfield DD, Frick K, Patrie J, Kok P, Keenan DM, Gaesser GA, Veldhuis JD 2008 Effects of continuous versus intermittent exercise, obesity, and gender on growth hormone secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4711–4720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasey JL, Bouchard C, Wideman L, Kanaley J, Teates CD, Thorner MO, Hartman ML, Weltman A 1997 The influence of anatomical boundaries, age, and sex on the assessment of abdominal visceral fat. Obes Res 5:395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Hall M, Buysse DJ, Manuck SB 2007 Self-reported sleep quality is associated with the metabolic syndrome. Sleep 30:219–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Plat L 2000 Age-related changes in slow wave sleep and REM sleep and relationship with growth hormone and cortisol levels in healthy men. JAMA 284:861–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworoger SS, Yasui Y, Vitiello MV, Schwartz RS, Ulrich CM, Aiello EJ, Irwin ML, Bowen D, Potter JD, McTiernan A 2003 Effects of a yearlong moderate-intensity exercise and a stretching intervention on sleep quality in postmenopausal women. Sleep 26:830–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson BA, Rosen T, Johannsson JO, Johannsson G, Oscarsson J, Landin-Wilhelmsen K 1995 Cardiovascular risk factors in adults with growth hormone deficiency. Endocrinol Metab 2(Suppl B):29–35 [Google Scholar]

- Waters DL, Qualls CR, Dorin RI, Veldhuis JD, Baumgartner RN 2008 Altered growth hormone, cortisol, and leptin secretion in healthy elderly persons with sarcopenia and mixed body composition phenotypes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63:536–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner RN, Wayne SJ, Waters DL, Janssen I, Gallagher D, Morley JE 2004 Sarcopenic obesity predicts instrumental activities of daily living disability in the elderly. Obes Res 12:1995–2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MW, Probst MM, Gruber JJ, Berger R, Boone Jr JB 1996 Differential effects of exercise training intensity on blood pressure and cardiovascular responses to stress in borderline hypertensive humans. J Hypertens 14:1369–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA 2007 Effect of exercise on blood pressure control in hypertensive patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 14:12–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AT, Clemmons DR, Underwood LE, Ben-Ezra V, McMurray R 1987 The effect of exercise on plasma somatomedin-C/insulinlike growth factor I concentrations. Metabolism 36:533–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rarick KR, Pikosky MA, Grediagin A, Smith TJ, Glickman EL, Alemany JA, Staab JS, Young AJ, Nindl BC 2007 Energy flux, more so than energy balance, protein intake, or fitness level, influences insulin-like growth factor-I system responses during 7 days of increased physical activity. J Appl Physiol 103:1613–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly RM, Dunstan DW, Owen N, Jolley D, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ 2005 Does high-intensity resistance training maintain bone mass during moderate weight loss in older overweight adults with type 2 diabetes? Osteoporos Int 16:1703–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]