Abstract

Objective

To develop and implement a course that develops pharmacy students' leadership skills and encourages them to become leaders within the profession.

Design

A leadership course series was offered to pharmacy students on 2 campuses. The series incorporated didactic, experiential, and self-directed learning activities, and focused on developing core leadership skills, self-awareness, and awareness of the process for leading change.

Assessment

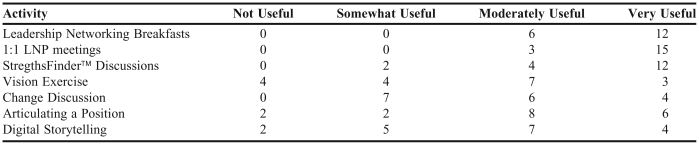

Students reported increased knowledge and confidence in their ability to initiate and lead efforts for change. The learning activities students' valued most were the StrengthsFinder assessment (67% of students rated “very useful”) and a Leadership Networking Partners (LNP) program (83% of students rated “very useful”).

Conclusion

Teaching leadership skills poses a significant challenge in curriculum development and requires multifaceted course design elements that resonate with students and engage the practice community. Addressing these requirements results in a high level of student engagement and a desire to continue the development of leadership skills.

Keywords: leadership, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

A determining factor in the success of many new pharmacy graduates will be their leadership skills. More specifically, success will be determined by their ability to influence practice change. Just as excellence in patient care and practice management roles is dependent on a unique set of knowledge, skills, and values that must be acquired by the practitioner through formal education, the role of “change agent” also requires a unique set of knowledge, skills, and values that can be formally developed in students.1,2

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Guideline 17.3 suggests that leadership may be a desirable quality that could be assessed at the time of admission.3 However, few would suggest that incoming pharmacy students possess all the skills needed to lead change. The pharmacy educational experience must develop these skills further.

Recent editorials and reports on leadership have focused primarily on leadership among pharmacy faculty members.4-7 Fewer scholarly publications have reported on leadership and student pharmacists.8 When considering student leadership development, efforts to develop student organization leaders seem like an obvious place to start. In fact, Guideline 22.1 reinforces that student governance is an opportunity for development of leadership and professional skills.3 However, given that all pharmacists will have greater success if they possess core leadership skills, development through positional roles in student organizations cannot be the only area of focus. Not all students will serve in a positional leadership role, nor will most pharmacists pursue this form of leadership.

The need for faculty and administrative commitment to fostering leadership development in students is stated in ACPE Guideline 23.3 In addition, Appendix B of the ACPE Guidelines specifically lists development of leadership skills as part of the foundation of the curriculum.3 Furthermore, ACPE states in Guideline 26.1 that programs for faculty development should “provide strategies to develop consistent socialization, leadership, and professionalism in students throughout the curriculum.”3 Yet, this distinct skill set is not frequently discussed or deliberately designed into curricula.

At the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy, a commitment has been made to develop graduates that will be leaders in the profession and health care through innovative education, management, and practice improvements. To that end, several educational initiatives have been undertaken to facilitate the acquisition of the knowledge, skills, and values that support effective leadership. This manuscript describes 1 of these educational initiatives, an elective course designed to raise awareness of leadership and exercise core leadership skills in students. Specifically, this elective course emphasizes methods for facilitating positive practice change and principles for influencing organizations irrespective of position or title of authority.9

DESIGN

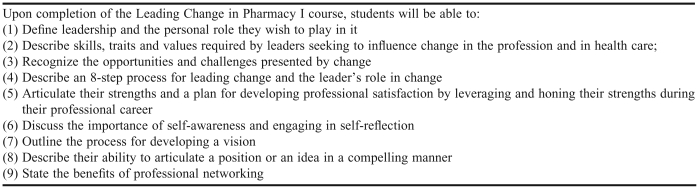

The University of Minnesota is a multicampus institution with pharmacy faculty members and students at the Twin Cities and Duluth campuses. The Leading Change in Pharmacy course series consists of 2 semesters of a 2-credit elective course offered on both campuses. This series serves as the learning environment where students begin to understand several key concepts in leading change and engage in classroom and self-directed learning activities that facilitate their growth as leaders. The series has 3 primary goals: developing an awareness and understanding of leadership, assisting participants in delineating a process for leading change and the leader's role in managing this process, and encouraging students to practice core leadership skills. To achieve these goals, the instructional objectives presented in Table 1 were designed for the Leading Change in Pharmacy I course.

Table 1.

Instructional Objectives of a Course for Pharmacy Students on Leading Change

Prior to offering this series, the instructors provided an optional 6-hour leadership seminar in a third-year pharmaceutical care skills course; the seminar had been offered since 2002 on the Twin Cities campus and since 2006 on the Duluth Campus. The instructional design for the Leading Change in Pharmacy series was based on student response to activities used in the seminar. For instance, lecture for the explanation of concepts was deliberately balanced with discussion-based, small-group activities for application of concepts. A balance of theoretical and practical instruction was also required, along with a deliberate bridge between the 2 approaches. As a result, instructors presented concepts in source materials, bridged the concepts to personal and professional examples, and involved pharmacists who demonstrated how concepts are used in practice. In addition, due to the personal nature of leadership, students appreciated opportunities for self-directed learning and opportunities for creativity in expressing their learning. Finally, it was determined that the principles of self-reflection needed to be regularly reinforced and that a good starting point for this instruction was exercises related to personal strengths.

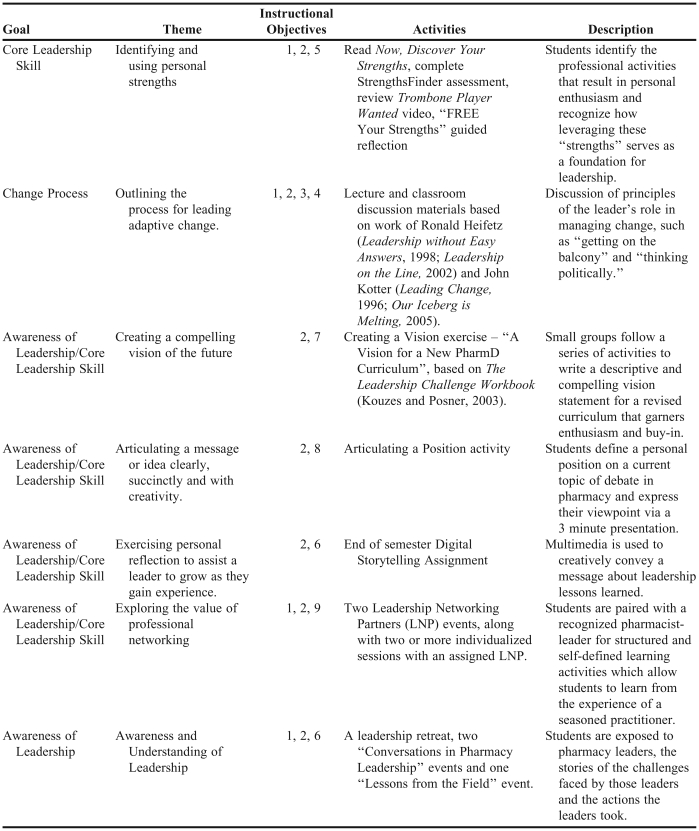

Phar 6237: Leading Change in Pharmacy I is the 2-credit elective course offered in the fall term. The course was first offered in fall 2007, and had an enrollment of 7 students on the Duluth campus and 23 on the Twin Cities campus. Although second and third year (P2 and P3) students are eligible to enroll, participants were generally P3 students, due to the workload demands of the P2 curriculum. Seven themes formed the framework for instruction during the semester: personal strengths, leading change, creating a vision, articulating a message, personal reflection, networking, and leadership awareness. Each theme included 1 or more learning activities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of Goals, Themes, Objectives, and Activities of Phar 6237 - Leading Change in Pharmacy I

Evaluation of the instructional design and student learning experience was completed via an end-of-course evaluation and 2 focus groups, each with student course participants and Leadership Networking Partners (LNP) program pharmacists (see “Networking” section below). In addition, one of the LNP pharmacists served as an external reviewer, reviewing a 40-page report describing the course initiative. The report included discussion of foundational concepts and rationale for the course design, samples of assignments and student work, focus group findings, course evaluation summaries and comments, and reflections from the instructors on the functioning and successfulness of the course. This consultant was chosen for her experience as a professional trainer and with teaching leadership content. Use of all evaluative course information was reviewed and exempted from full committee review by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee.

Personal Strengths

The first theme was personal development through the identification and use of personal strengths. Several learning activities were employed (Table 2) and considerable time was devoted to this topic–approximately 5 hours of in-class time plus work completed outside of class. Students were introduced to concepts of personal and organizational management that are rooted in the belief that those individuals who are most successful and satisfied in their careers focus on developing and using their strengths rather than on correcting weaknesses. This philosophy is a prerequisite for engaging in leadership development: if people do not find roles in their careers that use their strengths most of the time, they are unlikely to be highly engaged in their environment; and unlikely to seek to influence (or lead) in this environment.

Leading Change

The second theme focused on the process for leading adaptive change. Students were introduced to the difference between “technical” and “adaptive” problems. Students learned how successful leaders view change, the defined steps in facilitating adaptive change, and the role of leaders in that process. Through discussion, examples were both provided to and requested from students and used to introduce the change process and the leader's role in change.

Creating a Vision

The third theme addressed how to create a compelling vision of the future that would garner enthusiasm and buy-in from a group that a leader seeks to influence. One of the most important traits of successful leaders is the ability to create a picture of a “future” in their mind's eye and then communicate this vision to others in a way that makes others develop a desire for that future and seek to help in creating it. To facilitate student learning in this theme, the instructors developed a series of small-group discussions that walked students through a process for creating an “envisioned future” for an area in which change would occur.

Articulating a Message

The fourth theme addressed how to articulate a message or idea clearly and with creativity. An “Articulating a Position” activity was developed to give students the opportunity to work on persuasiveness and extemporaneous speaking skills. In this activity, each student was assigned a contemporary pharmacy issue that was under debate within the profession. Students researched the issue, defined their personal position, and prepared a 3-minute presentation describing and justifying their position, which was not unlike having the floor in a committee meeting. Following the presentation, a moderator facilitated a discussion where audience members challenged the speaker's position.

Personal Reflection

The fifth theme addressed the importance of personal reflection in allowing leaders to grow as they gain experience. As Dan Pink counseled attendees at the 2007 AACP Annual Meeting, “story” is a method of connecting with an audience in a powerful, meaningful, and memorable way.10 His guidance, coupled with the work of Educause, served as the inspiration for a “digital storytelling” assignment.11 Digital storytelling is the practice of combining narrative with digital media , including images, sound, and video, to create a short movie that delivers a poignant message. Students were assigned the task of creating a “digital story” that asked them to reflect on the question, “What have I learned about leadership?”

Networking

The sixth theme involved exploring the value of professional networking. Successful leadership relies on networking skills. The relationships established through networking create opportunities to engage and develop new ideas, develop important collaborations, and establish a shared vision for change. Specifically, a Leadership Networking Partners (LNP) program created opportunities for students to see a recognized change agent “in action” but also “behind the scenes.” Each student was paired with a pharmacist from the community, to learn about the pharmacist's career path and his/her experience leading change. Students attended work-related meetings with pharmacists, debriefing before and/or after the meetings to discuss how the effort to lead change is shaped by several variables, including politics, barriers, and history. These student-pharmacist relationships were further facilitated by a combination of assigned, structured activities, as well as through activities defined individually by the LNP team. While there was no set requirement for the number of hours students spent with their partners each semester, a general guideline was approximately 10 hours.

Leadership Awareness

The final theme involved recognizing the skills, traits, and values of leaders, along with developing a personal awareness and commitment to leadership in professional life. The fall semester course began with a 1.5 day retreat, which focused on the following themes: positional versus non-positional leadership, personal commitment to excellence, the power of teams, and the importance of self-reflection skills in those who choose to lead. This retreat created a foundation for the concepts and material taught in the course. During the course, students also participated in 3 events designed to expose them to pharmacy leaders, the challenges faced by those leaders, and the actions those leaders took. These events included 2 “Conversations on Pharmacy Leadership” that brought a national and a local speaker to campus to address a leadership topic through a conversation with a moderator and the audience. In addition, in a “Lessons from the Field” event, a new practitioner was invited to talk to the class about his/her first years of practice.

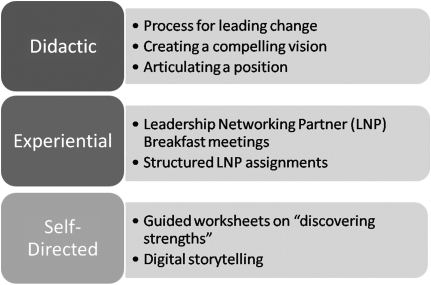

Course Structure

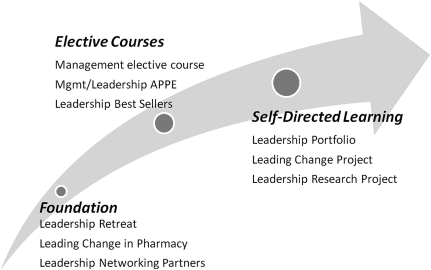

Learning activities were selected specifically to incorporate didactic, experiential, and self-directed learning (Figure 1). This multidimensional learning approach was deliberately chosen to maximize student engagement, aid student understanding of concepts, assist with application of the material, and encourage retention through contextual, active learning.

Figure 1.

Structural design of a pharmacy course on leadership and leading change.

As this course initially was developed, it greatly benefited from a team-based instructional model that included faculty members on each campus. Weekly meetings were held to determine each person's contributions and the agenda for the class period. Developed materials were always reviewed by at least 2 instructors before use. Instructor expertise was optimized by selecting a “point person” for topics, based on interest and experience. In addition, follow-up on each class period was conducted via phone or e-mail to discuss student response, the activities that worked or did not work, and whether the plan was completely executed or one campus had work yet to complete.

Instructors wanted to create an environment where student work and commitment were not influenced by the pursuit of a certain grade, but instead by the desire for personal growth and development. Final course grades were pass/fail. The decision to grade this course on a pass/fail system was based partially on the desire to create an environment that mirrored the leadership concepts discussed in the course. For instance, the course taught that effective leadership is rooted in a selfless interest in serving others or working for the greater good rather than in a self-serving desire for personal gain or reward (eg, a good grade).

In addition, as described above, many of the activities were based on personal reflections and experiences. Evaluating and assigning letter grades to the outcomes of these activities (eg, as in the digital story activity) would not have recognized the personal growth that might have occurred, a result that may have been more important than the product or grade. Rather than focusing on grades, it was decided that efforts were best placed on feedback. Performance on course assignments was rated using rubrics. For instance, in the Articulating a Position exercise, peers evaluated each other using a rubric with criteria that included organization and clarity, support of the position, responses to questions on the position, and presentation style. Ratings provided via rubrics were for formative feedback purposes and not for assignment of a letter grade.

ASSESSMENT

The end-of-course evaluation was completed by 18 of 30 participants (60%). Quantitative student ratings of the various learning activities employed in the course are outlined in Tables 3, 4, and 5. Additionally, 2 focus groups with LNP pharmacists and 2 student focus groups were held to discuss reactions to the course and suggestions for improvement, with particular attention to the networking experience. Evaluative comments generated via the focus groups are reported below in the sections reporting on Personal Strengths, Personal Reflection, and Networking.

Table 3.

Pharmacy Students' Responses on an Evaluation of Activities in a Course on Leading Change in Pharmacy, N = 18

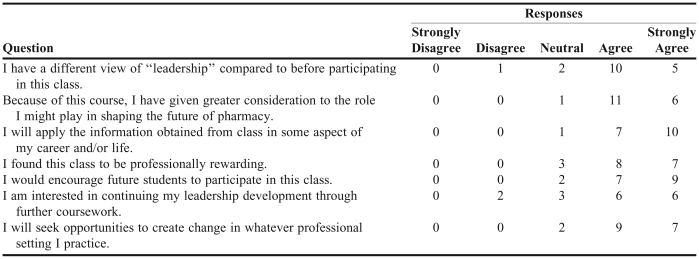

Table 4.

Pharmacy Students' Evaluation of the Usefulness of Activities in a Course on Leading Change in Pharmacy, N = 18

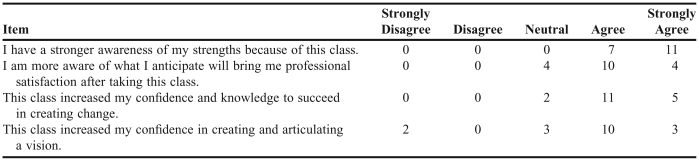

Table 5.

Pharmacy Students' Responses to Items on an Evaluation of a Course on Leading Change in Pharmacy, N = 18

Findings

Personal Strengths

The strengths section of the course was designed to get new graduates “off on the right foot” by creating an awareness of their personal strengths. As stated by our consulting reviewer: “Using this material with emerging practitioners makes great sense and I believe has the capacity to help new pharmacists avoid some hard career lessons by providing them with more self-awareness to seek fulfilling roles that take advantage of their strengths.”

On the course evaluation, 100% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they had a stronger awareness of their strengths as a result of the course (Table 2). In addition, 94% of students indicated that the exercises were “very” or “moderately” useful (Table 3). Many positive comments were received from the focus groups about the strengths theme. When asked what students thought was most beneficial from the course, responses included:

“Strengths - these really changed the way I look at things and how I focus on my strengths.”

“The Leadership book to learn my strengths - the book was wonderful!! I loved it and was telling everyone about it. And actually some of my friends and parents went out to buy it. It was very rewarding to see what strengths I have and then be given examples on how to use them.”

“StrengthsFinder was useful to get to know yourself in a more concrete and defined manner. Info can be used for further self reflection in choosing a career, signing up for activities/volunteer opportunities, giving others insight into your personality by using a few key words.”

Personal Reflection

In the course evaluation, the digital storytelling activity was rated as “very” or “moderately” useful by 61% of students. Suggestions for improvement called for introducing the assignment earlier in the course and giving students more than a month to complete the work, and for breaking the process into smaller assignments. This activity required a reasonably high degree of competency in navigating digital media, and the students' levels of skill varied. Little guidance on the content or technology of the assignment was given, deliberately leaving students to their own ingenuity and self-directed learning. However, guidance was provided on storytelling and the elements of a strong story. Students rose to the challenge. One student responded during a focus group that the digital storytelling was the most useful aspect of the course

On the last day of class, 3 videos from the student storytelling assignments were chosen to show the class and LNPs. These examples were chosen for their range of creative communication, focus of their messages, use of creativity/artistry, degree of reflection, and emotional impact. One student commented that she wanted to re-work her digital story after being inspired by the ideas seen in other students' work. Another student commented that she wanted to create another digital story.

In general, while the assignment was nontraditional and required a significant investment of time from students, this assignment was a highlight and, in many respects, a capstone of the course. As described by our consulting reviewer: “The final video project showed how much the students learned and allowed them to use their creativity in telling stories that reflected that learning. When these were shown to the students and pharmacists, I can say there were men and women with tears running down their cheeks.”

Networking

One-hundred percent of students indicated that the LNP Breakfast Meetings and one-on-one meetings were “very” or “moderately” useful. Pharmacist participants also indicated that they saw a clear connection between this program and development of leadership skills. A pharmacist stated during a focus group session: “I think what students took away was seeing tangible evidence of how leadership can shape practice (ie, seeing work being done outside of traditional dispensing, seeing patients, seeing interactions between me and management/the rest of the care team, etc). They also learned about the barriers/successes one goes through when trying to create change and about different approaches to effecting change.”

In addition to student ratings of the LNP experience, student focus groups were conducted on each campus to determine student response to the program and ideas for improvement. Student response was positive with respect to the activities in which partners engaged, as well as the relationships developed through the initiative. Students commented specifically on how the LNP experience demonstrated “the value of becoming acquainted with other professionals in my field” and “that I am able to shape my career based on my personal interests and strengths.” Students described unique learning experiences that cannot be replicated in a classroom, such as participating in organizational planning sessions and professional association policy meetings. Students saw the value in these experiences, commenting that they witnessed “change management in action that gave real-life situations to theories touched on in our class” and experienced “the difficulties in implementing changes…across an organization.” Because of the relationships and learning experienced in this component of the course, students ultimately described this initiative as “a major incentive to continue in the Leading Change course series.”

Although the instructors anticipated that the sessions would be useful for students, the response from pharmacists, via the focus groups, was surprising--they reported on the highly motivating experiences of appreciating the open-mindedness of the students, participating in two-way discussions, learning about students' interests and plans, and seeing students as “the future of pharmacy.”

Participants made excellent suggestions for “jumpstarting” the relationship between student and LNP, including the provision of bios and the sharing of electronic portfolios. Pharmacists expressed interest in a year's commitment with their students. Pharmacists also expressed significant enthusiasm for the structured LNP Assignments (which addressed topics such as “positive deviance” and “appreciative inquiry”) that were available as a discussion point for one-on-one sessions.

The program was designed to meet a learning need of the students, and the value to pharmacist partners is understandable. However, there have been additional unanticipated outcomes. As a pharmacist reflected during a focus group session: “As the LNPs have become engaged, there's been a lot of ‘buzz’ and discussion spreading about ‘the class,’ what's been taught, who is involved, how to become involved. That is generating numerous professional relationships and relationship-building skills among Partners and the larger community. Furthermore, the class has sparked some very, very interesting reflection by the community partners and they have taken material back into their practices to use in staff development.”

Leadership Awareness

Table 5 outlines student assessment of the impact the course had on the students' awareness of leadership traits and their ability to play a role in leading change. Eighty-three percent of respondents indicated that they had a different view of leadership because of participating in the course, and 94% indicated that they would give greater consideration to the role they might play in shaping the future of their profession.

Course Series Continuation

Although the majority of participants were in their third year with only 1 semester left on campus, 71% of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they would be interested in continuing their leadership development through additional coursework. Fifteen of 30 students enrolled in the second semester of the Leading Change in Pharmacy Series.

DISCUSSION

Reflecting on the goals of the course, the experience gained from course delivery, and the feedback received from participants, several successes and challenges in this initial offering can be identified. The work related to identifying and using personal strengths was one of the areas of greatest success, both in terms of ratings and comments from students and instructors' observations of learner engagement in the material. The philosophy of focusing on leveraging strengths and minimizing weaknesses resonated with students and significantly altered their perceptions of personal development. A challenge was specifically helping students link their identified strengths to everyday activities. Identifying strengths and knowing where and how to apply them most effectively are 2 separate steps; the second step is the more difficult. In future offerings, more attention will be paid to helping students make this connection between strengths and activities/roles.

Another learning activity that generated the greatest participant enthusiasm was the LNP initiative. Focus group results combined with anecdotal comments from both students and pharmacists demonstrated significant regard for the value of these experiences with respect to student learning and the power of the relationships that were forged, many of which are expected to be enduring. An unplanned outcome from this initiative was powerful community engagement. Although a small group of 19, the pharmacist LNPs have quickly embraced the College's vision for developing a curriculum on leadership and have become strong advocates for the LNP program. Although this commitment takes time and energy, pharmacist LNPs have gone beyond the required meetings/discussions and scheduled additional meetings, brought their students to networking opportunities, read books and articles that the students are examining, and committed to ongoing relationships. Pharmacist LNPs are also participating in the College's leadership-oriented continuing education programs and recruiting additional pharmacists to participate in the LNP program. Observing this success, the authors have begun to consider how this LNP program's “ripple effect” can be more formally quantified in terms of its impact on leadership development in the Minnesota pharmacy community and relationship building between pharmacists and the College.

The digital storytelling assignment played a significant role in creating an emotional investment in the course and its lessons, both on the part of students and the LNP pharmacists. Due to time restraints, only selected stories developed by students were shown to the full group of students and pharmacists during the final session of the semester. Following this viewing, both pharmacists and students requested that all stories be posted online for review on their own time. In addition, one student was approached by a pharmacist LNP who wished to purchase the student's digital story for use by a local art council to demonstrate the power of blending artistic expression with learning around a non-art topic. Another student's digital story made its way to the orthopedic department of a local health-system where the director requested that the entire staff view it.

The Articulating a Position activity was also successful in challenging students to clearly communicate in a manner often required of those who seek to lead change. We observed the sessions to be lively, with students actively engaged in challenging one another. Giving permission for students to act like someone else, in an effort to provide their colleagues with the experience of having to think on their feet and defend their position, seems to have been a positive qualifier in the assignment. In addition, students reported enjoying hearing each other's opinions and learning about topics on which they had little prior knowledge. In recognition of the importance of leaders staying informed on current professional issues and given the success of this activity, future course offerings will not only maintain this activity but also interweave additional dialogue on contemporary issues in health care delivery throughout the semester.

The creation of a vision was a new and modest effort. While the authors have developed many vision statements and guided groups through this process, more experience is needed in constructing this exercise as a learning opportunity. In particular, there was a love/hate response when students were asked to establish a vision for curricular reform at the College of Pharmacy. For example, a student described feeling “used” to do work that should be done by the Curriculum Committee. However, another student suggested in the course evaluation that learning activities gave students the chance to “work on more ‘real’ pharmacy issues—like we did with the visioning statement.” Other comments indicated that the link between visioning and leadership needed to be more thoroughly explained at the outset of the assignment and the questions on the assignment worksheets were confusing and should be refined. These issues likely contributed to only 56% of respondents indicating that the activity was “very” or “moderately” useful.

The development of learning opportunities that provide basic knowledge and skill in leadership is a special challenge. To be successful, instructors must engage students in more than reference materials, lectures, and discussions. Substantial effort must be placed on the development of practice-relevant, hands-on activities. Leadership instruction must also seek to combine traditional didactic instruction with experiential education opportunities and self-directed learning. Through a careful sequence of learning activities, students can achieve increased awareness of leadership concepts and also an appreciation of the value these activities have in their professional development. To that end and given the successes of the Leading Change in Pharmacy course series, the authors have developed an 18-credit curricular emphasis in leadership, which has been approved by the College of Pharmacy faculty (Figure 2). As part of this emphasis, students will build additional skills through a “leading change” project, maintaining a leadership portfolio, completing a research project focused on an area of leadership, and exploring management and leadership issues through an elective classroom experience and an elective advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE).

Figure 2.

Future emphasis area for a pharmacy course on leadership and leading change.

As we continue to evaluate the instructional outcomes of these courses and our curricular emphasis, we are considering which elements of this work should be included in a core curriculum for all students and which should be offered as electives. We also will pursue a longitudinal evaluation plan that will include alumni and employer surveys assessing perceptions and performance of graduates on leadership skills, while also examining traits and values.

We have found that investing in this type of instruction creates a powerful return for student pharmacists, pharmacists, and the academic institution. While community engagement and positive relationships between the College and pharmacist LNPs are not easily quantified, they are apparent and important. The potential impact of facilitating the growth of change-sensitive practitioners eager to assume leadership roles is also difficult to estimate. However, these outcomes are tangible and substantial, amplifying support for continuing efforts to formalize and expand leadership instruction in colleges and schools of pharmacy.

SUMMARY

Teaching leadership skills poses a significant challenge in curriculum development and requires multifaceted course design elements that resonate with students and engage the practice community. Leading Change in Pharmacy addressed important elements for establishing a foundation for leadership, including knowledge of strengths and the importance of reflection. It also provided an opportunity for development of skills important for leadership, including the ability to articulate a vision and effectively persuade others on professional issues. Creating an opportunity to learn from faculty members as well as recognized leaders from the local pharmacy community proved to be one of the most positive elements of course design. Evaluations from both students and practicing pharmacists suggest that the course will serve as an effective tool in preparing students to lead change upon entry to the profession.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc, in providing an endowed gift to the University of Minnesota for support of student leadership development. This gift supported course-related events and the acquisition of resources used in the development of this instruction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Astin AW, Astin HS. Leadership Reconsidered: Engaging Higher Education in Social Change. Battle Creek, MI: W.K. Kellogg Foundation; 2000. pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Web site. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.DOC. Accessed January 14, 2009.

- 4.Yin AY, Altiere RJ, Harris WT, et al. Leadership: the nexus between challenge and opportunity: reports of the 2002-2003 academic affairs, professional affairs and research and graduate affairs committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67 Article S05. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penna R. The Rho Chi lecture: the academy as leader. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67 Article 78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells BG. Academic leadership: one dean's perspective. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:459–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean JO. Characteristics and skills of successful academic leaders. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:207–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Hayes M. Effective leadership and advocacy: amplifying professional citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traynor A, Sorensen TD. Grassroots leadership: being an agent for change in pharmacy. Pharm Student. 2003;September/October:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pink D. Keynote Address. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Annual Meeting; July 15, 2007; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 11.7 Things You Should Know About Digital Storytelling. Educause Web site. http://connect.educause.edu/Library/ELI/7ThingsYouShouldKnowAbout/39398. Accessed January 14, 2009.