Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of commitment to change (CTC) statements on behavior or practice change after a continuing pharmacy education (CPE) program, and to assess the percentage of CTC statements that are linked to program objectives.

Methods

Following a CPE program, 33 participants were asked to complete a CTC statement and describe changes that they planned on making in their behavior as preceptors. Six months later participants were asked to return the CTC statement and note the status of the change.

Results

Twenty-eight participants completed the CTC. Twenty-one (75%) participants returned the CTC statement 6 months later with a status report. Seventy percent of the 56 changes described by the 21 participants had been fully implemented. The majority of the changes (88%) matched program objectives.

Conclusion

Writing a CTC statement following completion of a CPE program may positively affect behavior change.

Keywords: commitment to change (CTC) statement, continuing pharmacy education (CPE), preceptor

INTRODUCTION

Continuing pharmacy education (CPE) is required for re-licensure of pharmacists in all 50 states of the United States. The intention of this requirement is to protect the public's safety and well being, given the rapidly changing nature of pharmacotherapy and disease state management. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, the accrediting organization for CPE, reported that in the 2004-2005 academic year, over 22,000 programs were offered that served roughly 3.5 million pharmacists (written communication, June 27, 2006). While there is no financial data available, one would suspect that CPE is a multimillion dollar enterprise.

Given this investment of time and money on the part of individual pharmacists, employers, and professional associations, and the critical need for patient safety, documenting the learning and practice changes resulting from CPE is essential. There is a reasonable body of evidence supporting the conclusion that some types of continuing medical education can positively impact physician behavior and change.1 In their systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies on changing physician performance, Davis et al found that educational strategies such as reminders of new practice procedures and information, patient-mediated interventions, outreach visits, information from opinion leaders, and multi-faceted activities could positively affect physician behavior. Conversely, traditional formal conferences without specific reinforcement strategies had little impact on physician behavior .1

There is little evidence documenting the outcomes of CPE. Documented changes as a result of CPE include emphatic responses to written stimuli and role play,2 documentation of clinical interventions and monitoring of patient outcomes,3 and confidence in ability to provide pharmaceutical care and identify and resolve drug-related problems and patient monitoring.4 Changes in short-term and long-term knowledge as well as changes in attitudes following completion of a CPE have been reported.5-7 The evidence documenting the results of CPE is limited and is primarily focused on attitudes and knowledge. It is not clear how CPE impacts behavior and practice change, and ultimately patient-based outcomes.

Commitment to change statements (CTC) have been successfully used in medicine to affect and measure practice change.8-10 These are simply written statements in which participants commit to making a change in their future behavior or practice. The statement may or may not be signed. This process draws on the psychology literature and is grounded in goal setting and promise keeping.11 The gist of the CTC model's effectiveness is found in the 3 questions asked of participants: “Will you make a change in your practice, based on participation in this program?” “Did you make the intended change?” and “What prevented you from making the change?”12 For example, one study reported that physicians who committed to making a change in their practice after an educational intervention were more likely to make that change than those participants who did not commit to making a change.9 Simply put, it appears that the exercise of purposively and deliberately thinking of behavior change and documenting that planned change in writing increases the likelihood of that change occurring. CTC statements have not been used previously in CPE to promote practice change.

The objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of utilizing CTC statements to encourage practice change following completion of a CPE program. For the purpose of this study, change implies behavioral change that is related to the participants teaching or precepting pharmacy students. The secondary objective of the study is to assess the percentage of participants' CTC statements that match or are closely linked to stated program objectives.

METHODS

Preceptors from Midwestern University Chicago College of Pharmacy were invited to attend the Preceptor Leadership Development Institute (PLDI), a CPE program. In addition, since the College was also seeking new preceptors, all registered pharmacists in the Chicago metropolitan area were also invited to attend. Approximately 7500 program brochures were mailed to pharmacists who met at least 1 of the 2 criteria. Follow-up mailings to the directors of hospital pharmacies and phone calls were also made by College leadership to encourage pharmacists to attend. Thirty-three pharmacists participated and completed the PLDI.

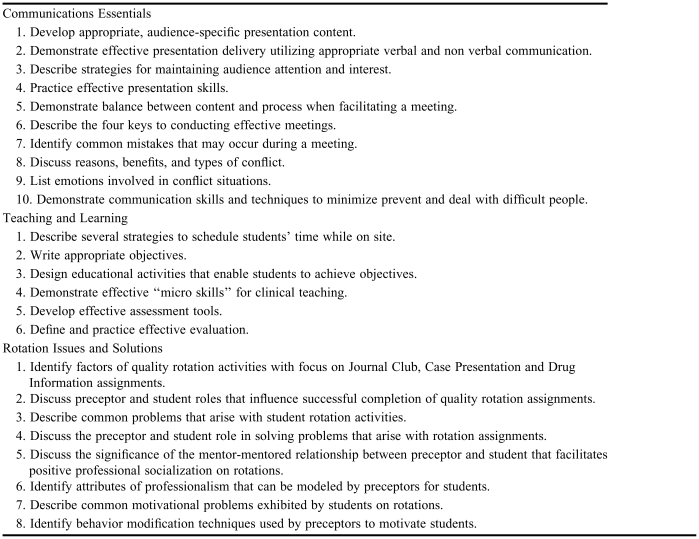

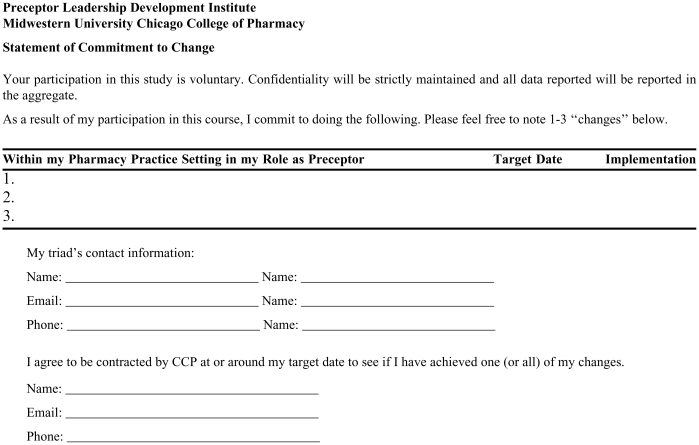

The PLDI was held on a Friday evening and all day the following Saturday in October 2005 on the Midwestern University campus. The PLDI was designed to enhance the teaching skills of pharmacists who are either currently serving as preceptors or who wish to become preceptors. Preceptors supervise and teach pharmacy students during advanced pharmacy practice experiences in their fourth-professional year. The PLDI covered topics such as communication skills, writing objectives, evaluating student performance, and planning student activities. A list of program objectives is given in Table 1. The PLDI was taught by faculty members from the College, the majority of whom were clinical pharmacists. The faculty team was integral in developing the program. The PLDI was interactive, and used a variety of learning techniques, including mini lectures, case-based group discussions, role play, individual written reflections and exercises, and demonstrations. The course was purposely designed to provide for maximum interaction between participants and faculty members, as well as among participants, as interactive-learning techniques in continuing medical education have been demonstrated to maximize change in clinical practice.1 At the conclusion of the program, pharmacists were asked to complete a commitment to change form. The form was included in their instructional materials, which they received on the first night of the program; however, participants were not informed or instructed on how to complete the form until the conclusion of the program. This was a voluntary activity, and participants were guaranteed that their name and responses would remain confidential with the investigator. On the CTC form, participants identified 1 to 3 changes they were committed to making at their practice site regarding their teaching as a result of the learning that occurred at the PLDI. They also listed a target date for implementation, and if desired, noted contact information from their assigned triad group, which was formed on the first day of the PLDI to complete various interactive exercises and discussions. The forms were collected and photocopied, then the originals were returned to the participants shortly after the program completion. The CTC form can be found in Appendix 1. This project and the CTC form were reviewed by Midwestern University's Institutional Research Board and the project was determined to be exempt.

Table 1.

Preceptor Leadership Development Institute Course Objectives

Six months later, an e-mail was sent to all participants reminding them that they would soon receive a copy of their CTC form in the mail. The timeframe of 6 months had been used in other studies examining the effectiveness of CTC statements9 so it was thought that amount of time would be enough to implement changes in practice. Shortly after the e-mail was sent, a letter and the individual CTC statement were mailed to each participant. Participants were asked to reflect on the changes they had committed to making on their CTC and complete the form, noting whether or not changes were (1) fully implemented, (2) partially implemented, (3) could not be implemented at this time, or (4) would not be implemented. This rubric was developed from previous work by Lockyer et al.13 Follow-up e-mail reminders were sent to the sample 2 and 4 weeks after the initial mailing.

Each respondent's CTC was reviewed and changes noted on their CTC statements were recorded verbatim. Descriptive statistics (frequencies) were used to analyze changes and status of implementation to address the first study objective. Key words were identified in each change and matched to program objectives and then tabulated to address the second study objective. This was a manual process completed by the investigator.

RESULTS

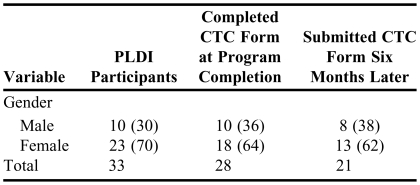

Twenty-eight (85%) of the participants completed and submitted the CTC form at the conclusion of the program. Twenty-one of the pharmacists returned the CTC form following completion of the PLDI for a response rate of 70%. Thirteen of these were experienced preceptors, and the remaining 8 were new preceptors (less than 1 year of experience). Limited demographic data were collected from the participants and are described in Table 2. While information regarding the specific practice sites of participants is not available, anecdotally, the participants were overwhelmingly from hospital and corporate community settings. The types of changes to which each participant committed are listed in Table 3, along with their assessment of the implementation of the change. Seven pharmacists who had submitted a CTC did not return the form and implementation status after repeated reminders.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data of Participants in a Preceptor Leadership Development Institute

PLDI = Preceptor Leadership Development Institute, CTC = Commitment to Change

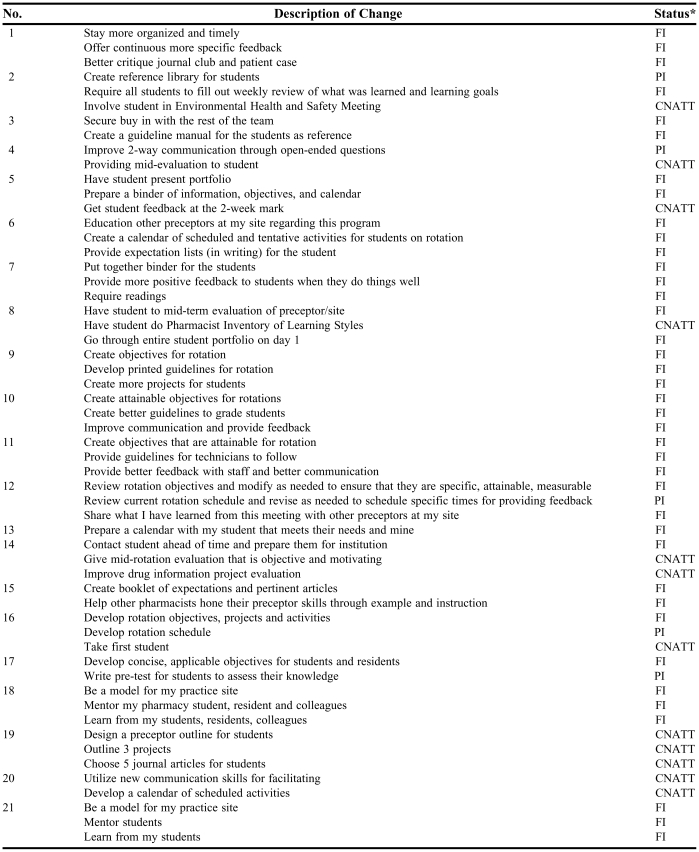

Table 3.

Participants' Commitment to Change Statements and Implementation Status After Completing a Continuing Pharmacy Education Program

*FI = fully implemented, PI = partially implemented, CNATT = cannot implement at this time, WNI = would not implement

Participants described 1, 2 or 3 changes that they planned to make, with the majority of participants noting 3 changes. Out of the 56 intended changes, 39 (70%) were fully implemented by the participants. Five (9%) of the changes were noted as partially implemented, and 12 (21%) of the changes were noted as “can not implement at this time.” None of the participants selected the option “would not be implemented.” The majority of respondents reported that changes were fully implemented.

Participants noted a variety of reasons why changes could not be implemented at this time. Those reasons included time constraints, participant forgot, did not yet have a student to precept, staffing issues prevented changes from occurring, rotation had not yet started at time of data collection, or left previous place of employment.

A review of the kinds of changes that participants noted (Table 3) indicates a strong relationship to the course objectives. Eighty-eight percent of the participant changes were closely aligned with program objectives. Only 7 CTC statements out of 56 were not directly linked to program objectives and were more global in nature. For example, “stay more organized and timely,” “secure buy-in with the rest of the team,” and “share what I have learned from this meeting with other preceptors at my site” are more enabling activities that may need to be accomplished first, before the individual preceptor can change his/her behavior.

DISCUSSION

The types of changes identified by participants ranged from specific with definite, measurable outcomes, to more abstract changes that are more continuous in nature. For example, one participant fully implemented “create attainable objectives for students.” This change is specific, has a defined endpoint, and is easily measured. On the other hand, another participant fully implemented “mentor my pharmacy student, resident, and colleagues.” This change is far more nebulous, less easily measured, and has no defined endpoint. Yet the participant noted that this change was fully implemented. The participant may have had a specific idea of behaviors that are embedded in this change, but it is not clear from the data provided how an external observer could verify that this change occurred.

The data were collected 6 months after the initial program. Thirty percent of the changes were partially implemented or noted as cannot implement at this time. This begs the question that if the data collection process had occurred 9 to 12 months after the program, would this have allowed participants more time to implement changes, or was the lack of change implementation a factor of variables other than time. For example, failure to fully implement the change could have been the result of the complicated nature of the change, conditions of the practice setting, lack of resources needed to make the change, or the level of the individual's commitment to making that change. One study examining the effect of CTC on practice change required participants to indicate on a rating scale of 1 to 5 how committed they were to making that change.8 Another approach would be to have participants decide on their own timeframe for implementation. In other words, participants would create a more detailed plan for implementing change that would encompass all the factors listed above. Further analysis examining other factors that could potentially affect the success of change implementation is needed.

The process of data collection, which included reminder e-mails and a mailing, could have served not only as part of the data collection process, but also as a reminder of the learning that that occurred and the participant's intention to implement a change. Davis had indicated in his review that reminders were an effective educational strategy that promoted change in physician behavior.1 The intersection of these 2 strategies (reminders and CTS statements) may be the catalyst for change.

The success of CTC models on effecting practice change may rest simply on the act of reflection after an educational intervention. Allowing participants time to reflect on what they learned, consider how to integrate that learning into their daily practice, and commit to changing practice, may provide the foundation for successful long-term implementation. The results of CTC statements inform CPE providers of what participants identify as key and valuable learning that occurred in the program. This learning could be intended and planned in the program, or it could be extracurricular. The analysis comparing participant changes to program objectives revealed that several participants noted changes that were not part of the planned program objectives. Why these changes were identified by participants deserves further inquiry and may provide valuable insights into adult learners.

Lastly, the CPE program used in this study focused on teaching and learning behaviors. Whether CTC statements would be equally effective on affecting practice change that is clinical in nature is not known. The level of autonomy and decision making differs between physicians and pharmacists. Pharmacists typically have less autonomy and this may negatively affect, the impact of CTC statements on affecting change in clinical practice.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. This was self-reported data; therefore, the reported practice changes were not verified. The study was limited by the possibility of participants “over reporting” change. This was a small sample, and participants may have been motivated to report variable results because of social desirability or other personal motivations. Further investigations into the impact of CTC statements could attempt to verify change through student or peer observations. It is not known whether the nonresponders did or did not make changes to their practice/behavior as a result of the program, so there was no comparison group. It is also not clear how the nonresponders differ from the respondents. This study would have benefited from a control group so that the CTC group could have been compared with a non-CTC group. Experience of the participants may have also impacted the degree of change. In other words, the more experienced preceptors may have been more likely to implement the changes in their behavior and the less experienced or new preceptors may have had a more difficult time implementing changes. Lastly, the timing of the data collection process may have affected the results. Data were collected about 6 months after participants completed the program (April 2006). The College's new APPE cycle begins in March of each year. Some participants may simply have not had the opportunity to work with students and implement their desired changes, and in fact, this explanation was noted by one of the participants.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study suggest that CTC statements may have a positive influence on affecting individual practice change as a result of CPE. Given the time and monetary investment in CPE nationwide, and the rapidly changing nature of health care, which directly impacts patients' health, it is critical that CPE be an effective mechanism for changing pharmacists' practice behaviors.

Appendix 1. Statement of Commitment to Change

REFERENCES

- 1.Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274:700–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.9.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolinsky D, Lantos R. An evaluation of a continuing education workshop on empathy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1986;50:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson BD. Distance education in a rural state: assessing change in pharmacy practice as a result of a pharmaceutical care certificate program. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barner JC, Bennett RW. Pharmaceutical care certificate program: assessment of pharmacists' implementation into practice. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1999;39:362–7. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen HY, Lee TY, Huang WT, Chang CH, Chen CM. The short-term impact of a continuing education program on pharmacists' knowledge and attitudes toward diabetes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fjortoft NF, Schwartz AH. Evaluation of a pharmacy continuing education program: long-term learning outcomes and changes in practice behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67 Article 35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fjortoft NF. Learning outcomes and behavioral changes with a pharmacy continuing professional education program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70 doi: 10.5688/aj700224. Article 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazmanian PE, Johnson RE Zhang A, Boothby J, Yeatts EJ. Effects of a signature on rates of change: a randomized controlled trial involving continuing education and the commitment-to-change model. Acad Med. 2001;76:642–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200106000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereles L, Lockyer J, Hogan D, Gondocz T, Parboosingh J. Effectiveness of commitment contracts in facilitating change in continuing medical education intervention. J Continuing Educ Health Professions. 1997;17:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakefield J, Herbert CP, Maclure M, et al. Commitment to change statements can predict actual change in practice. J Continuing Educ Health Professions. 2003;23:81–93. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazmanian PE, Waugh JL, Mazmanian PM. Commitment to change: ideational roots, empirical evidence, and ethical implications. J Continuing Educ Health Professions. 1997;17:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazmanian PE, Mazmanian PM. Commitment to change: theoretical foundations, methods, and outcomes. J Cont Educ Health Professions. 1999;19:200–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockyer JM, Fidler H, Ward R, Basson RJ, Elliott S, Towes J. Commitment to change statements: A way of understanding how participants use information and skills taught in an educational session. J Continuing Educ Health Professions. 2001;21:82–9. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340210204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]