Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the success of an elective course in Native American culture, health, and service-learning in fostering interest in experiences and careers with the USPHS Indian Health Service (IHS), and in shaping reflective practitioners.

Design

Students conducted readings, kept reflective journals, and engaged in discussions with Native American and non-Native American speakers. Students orally presented a Native American health issue and spent their fall break in Chinle, Ariz, providing social and healthcare services to the Diné under the supervision of IHS pharmacists. Opportunities for additional IHS experiences were discussed, as was discerning the Creator's call to a professional life of service.

Assessment

Thirteen of 15 students who had completed the service-learning course by January 2007 responded to a brief survey indicating that not only were the course objectives met, but the experiences had a lasting impact on professional mindset and career plans.

Conclusion

The course had a lasting impact on students' understanding of Native American social and health care issues, and on how they will practice their profession and live their lives.

Keywords: Indian Health Service, Native American, service-learning, reflection, cultural competence, USPHS

INTRODUCTION

The value of appropriately structured and intellectually meaningful service-learning experiences in promoting professional awareness and critical thinking skills has been recognized.1-21 Many schools and colleges of pharmacy have employed service-learning strategies within the didactic and experiential components of the professional program to meet several important curricular goals. Among these are to sensitize students to aspects of social justice and professional responsibility, promote cultural competence, augment critical and reflective thinking, hone professional communication skills, and dissect the intricate and multifaceted concept of “caring.”

Creighton University is a Catholic, Jesuit institution, and one of the core components of our mission is to be “women and men…for and with others.” Irrespective of religious tradition, this value lies at the heart of any meaningful service-learning experience. The “for others” phrase is consistent with the understanding that individuals engaged in service-learning must have an altruistic disposition and a sincere interest in the welfare of others. The “with others” component underscores the need for recognition that the community within which the students will work has hopes, dreams, ideas, talents, and energies to bring to bear on the problems being addressed, and that these meaningful contributions must be both acknowledged and respected.

This manuscript describes an elective course in Native American culture and health with a strong service-learning component. Pertinent learning objectives include: (1) analyzing Native American health care beliefs, traditions, disparities, and needs through interaction with Native health care professionals and healers, and through independent reading and research; (2) documenting reflective thoughts about issues related to course content and experiences through journaling; (3) stimulating the desire to advocate for underserved populations; (4) exploring the Jesuit concept of vocation (listening for the Creator's voice in directing one's life experiences) in shaping one's career path; and (5) stimulating election of additional educational experiences with the IHS. An overarching goal was to stimulate students to select practice careers in the IHS or with tribally-run clinics.

DESIGN

The concept of establishing a service-learning course in Native American culture and health began with a conversation between Creighton pharmacy faculty members and a 1998 Creighton pharmacy alumnus who was then practicing at an IHS healthcare facility in Chinle, Ariz (Navajo Nation). The course planners agreed to several learning objectives that were subsequently embedded within the course syllabus (available from the authors).

In fall 2003, a 2-credit-hour service-learning experience, Learning Through Reflective Service: The Native American Experience (PHA 341), was introduced. Unlike most elective courses offered within the School, students were required to apply for acceptance to this course. This action ensured that students were motivated to enroll out of a sincere and informed interest in Native American people, and that they would bring maturity, professionalism, responsibility, and sensitivity to their interactions with Native speakers and the Diné citizens they would encounter during the service-learning immersion. Once the instructors approved 4 qualified students for enrollment, notification was sent to all that the course was closed for that year.

A single 2-hour class was held each week during the 16-week fall term to allow sufficient time for guest speakers to share their wisdom while engaging students in meaningful dialog throughout the class session. Lessons were purposefully sequenced to first introduce students to the vocation concept and develop student awareness of the multiplicity of Native cultures. For the next several weeks, students explored issues related to professional practice opportunities with Native people, and Native health issues and challenges. Discussion topics included therapeutic areas of high morbidity, barriers to care, social welfare challenges (including poverty and its associated individual and community dysfunctions), the role of traditional foods, spirituality and ceremony in health and wellness, and political advocacy. Through these dialogs and their own practice experiences, students came to distinguish the often dispassionate, scientifically grounded “Western” concept of health and wellness from the more holistic Native view, which also emphasizes the importance of spiritual and relational aspects of well being. Students were then introduced to tribal governments and the concept of sovereignty in order to better understand the relationship between the IHS practitioners (predominantly US government employees) and the sovereign nations they serve.

Most lessons were accompanied by readings that prepared students for the learning and discussion that would take place in class. In addition to articles, chapters, and texts, students viewed a video on the history of the Canyon de Chelly (a site of historical and sacred importance to the Diné) and reviewed an Aberdeen Area CD that educated about Plains tribes and the boarding school experience. (The lesson schedule and readings are available from the authors.)

Students researched and delivered an oral presentation on a Native American health issue such as diabetes, tuberculosis, cardiovascular disease, alcoholism, prenatal care, or SIDS. Students made their presentations during a single class session. The presentations were scheduled a few weeks after the students returned from Chinle in order to give them the opportunity to consult with IHS pharmacists and other providers about their chosen topic, and they were encouraged to incorporate reflections on their Chinle experiences into their presentations.

The students also kept journals that were shared with the instructors on a monthly basis. The faculty members posed 2-3 questions after each class session to stimulate reflective thinking (Appendix 1). These questions were not meant to be an assignment in the strictest sense, and students were free to instead reflect on other aspects of the lesson that were particularly meaningful, troublesome, or inspirational to them. The faculty members commented on student reflections in writing and asked additional questions to prompt more in-depth thinking and reflection. The final reflection exercise was embedded in the course evaluation, and asked students to identify the most important things they had learned about Native American culture/health and about themselves as a result of taking the course. They were also encouraged to reflect on how (or if) their ability to hear the Creator's voice in shaping important life decisions had been heightened. (The complete course evaluation tool is available from the authors.)

All campus-based students participated in selected didactic activities outside the classroom, including a field trip to the Winnebago reservation to speak with a respected elder and former tribal chairman on the return of the tribe to a buffalo-enriched diet to combat diabetes, and to visit the buffalo herd he started and maintained. A troupe of Omaha ceremonial singers, drummers, and dancers came to the campus to explain the significance of the sacred drum and the meaning of their ceremonial regalia, and to demonstrate various styles of traditional dance. All enrolled students spoke with the elected tribal leaders of both the Winnebago and Omaha Nations in their Creighton classroom, and open and honest dialog about substance abuse and alcoholism was initiated by several of our Native speakers. One of the last presentations of the 2006 semester was made by a former PHA 341 student who had completed an IHS Junior Commissioned Officer Summer Externship Program (Jr. COSTEP) in Whiteriver, Ariz (Apache) the previous summer. The course concluded with a presentation by a noted Lakota actor, musician, and spiritual leader who shared how traditional values and practices augment physical and emotional health among Native people.

The capstone experience for the course was the week-long Chinle immersion, which occured over the fall break (approximately halfway through the fall term). This in-depth cultural experience was carefully planned by both the Creighton- and Chinle-based course faculty members, and designed to meet the needs of the students and the community. Students wrote learning goals for their immersion, which were shared with the onsite course planner in order to accommodate special interests. For example, one student was a single mother who expressed interest in talking with young women about balancing motherhood and school. As a result of her expressed interest, she was able to meet with students from the Chinle High School.

Service activities in which all students engaged were developed based on the needs of the Diné as understood by the IHS pharmacists and care staff members who lived and worked in the Chinle community. During the drive from Albuquerque to Chinle, the campus and web-based students had the opportunity to solidify the learning community initiated through shared classroom experiences. Creighton-based faculty members remained with the students through the first few days in Chinle. While onsite, the students stayed in the homes of IHS pharmacy and medical staff members, giving each the opportunity for personalized one-on-one discussion and reflection with a health care professional after their day's service work was done. Students reflected on 4 questions at the end of each day: (1) What did you see or do today that was uplifting, insightful, or inspirational? (2) What did you see or do today that was disquieting, troublesome, or problematic? (3) How did these experiences impact who you are becoming, both professionally and personally? (4) Did you hear the voice of the Creator in today's experiences? If so, how? While the last reflection question addressed the Jesuit concept of vocation, it was in perfect harmony with the traditional Native American view of spirituality which is fully integrated into all aspects of everyday life.

The first few days of the immersion were spent learning about the Diné community in and around Chinle through focused service to individuals and groups. An extended hike in Canyon De Chelly under the supervision of a Native health care professional began the week. The family of a Native IHS pharmacy technician hosted the group for an evening of conversation and culture and a meal rich with Native foods. Students then made rounds with a community health representative and a public health nurse as they visited elders in remote and often poorly accessible areas of the reservation to provide health and safety checks, and ensure they have items needed for survival. Students engaged in personalized service to elders by chopping wood, picking up trash, cleaning hogans, and/or making minor repairs to family dwellings and outbuildings. Students came to appreciate the challenges these elders face on a day-to-day basis to ensure that the most basic of human needs are met. Since most of these elders rely on others for transportation, students also gained a better appreciation of what patients went through to reach the IHS clinic in town. Patients in the waiting room of a rural IHS facility have often walked, hitchhiked or waited for rides that were often neither timely nor dependable. Students quickly realized that a patient “late” for an appointment was not necessarily being cavalier or irresponsible, and asking patients to “come back tomorrow” for a medication that was out of stock or to complete a needed laboratory test was simply not an option for many.

Through the professional practice component of the immersion, students gained an understanding of how IHS hospital and community clinic pharmacies functioned. They worked with pharmacists, observed and participated in patient counseling, spoke with the resident medicine man about incorporating traditional medicine and healing into patient care plans, and learned about career opportunities in the USPHS. When possible, the students also spent time in the Tsaile and Pinon clinics, allowing them to compare and contrast practice at various IHS facilities. In 2006, students worked for the first time with a Native Creighton University staff member in mentoring Chinle High School students who were applying for Gates Millennium scholarships. (For more information, refer to the Gates Foundation web site at http://www.gatesfoundation.org/UnitedStates/Education/Scholarships/GMS/)

PHA 341 students earned grades of Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory based on class attendance and active participation in class discussions, activities, and the Chinle service immersion. No examinations or quizzes were administered.

In January 2007, a brief survey of all students who had completed the PHA 341 elective was conducted to assess the extent to which course goals had been met and the impact the course had on their professional mindset and career plans. The survey was distributed electronically to the 15 individuals who had completed PHA 341, including 5 who had graduated and were then completing residencies or in practice.

ASSESSMENT

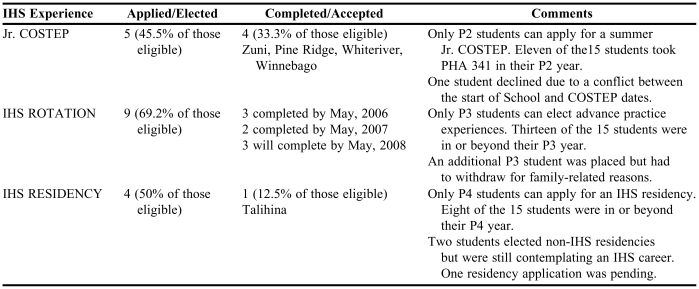

A major goal of the PHA 341 course was to expose students to IHS pharmacy practice and stimulate a desire to elect additional learning opportunities and/or careers with tribal people. The success the course has had to date in prompting PHA 341 “alumni” to apply for a Jr. COSTEP, elect an IHS advanced practice rotation (APPE), and/or apply for an IHS residency is summarized in Table 1. Over two thirds of the students who completed this service-learning experience elected to complete an IHS APPE. Approximately half of the students eligible to apply for a Jr. COSTEP assignment have done so, and all of the students who completed the application process were accepted into a summer program. Physicians who have elected IHS practice were strongly influenced by their IHS student or resident rotation experiences and our results would support the same positive impact in pharmacy.22 Of the 6 PHA 341 students who have completed an IHS advanced practice rotation, 4 have applied for an IHS residency, with 1 individual currently completing this experience. This graduate will be practicing in an IHS hospital pharmacy after completion of his residency. An additional student's IHS residency application was submitted in December 2006, but he ultimately elected to accept a position with a tribally run clinic in Alaska. Two other students wished to complete an IHS residency but were ultimately unable to due to previous commitments.

Table 1.

Additional IHS Experiences Elected by PHA 341 Students (N = 15)

HIS = Indian Health Service; Jr. COSTEP = Junior Commissioned Officer Summer Externship Program; P2 = second-professional year; P3 = third professional year; P4 = fourth-professional year

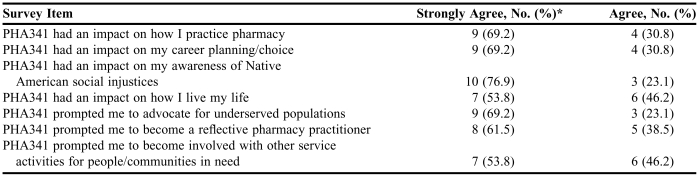

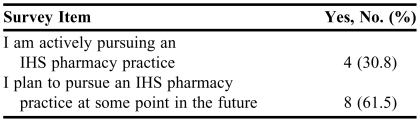

A second major goal of the course was to promote dispositions that lead to reflective practice and careers of service. Thirteen (80%) of the 15 individuals who had completed PHA341 responded to the survey e-mailed to them in January 2007. The respondents included 8 current students and all 5 graduates. Table 2 reports the opinion of the 13 former PHA 341 students related to course objectives, while Table 3 documents thinking about current and/or future career paths.

Table 2.

Student Response to Survey Questions Related to Course Objectives

*Likert scale: 4 = Strongly agree; 3 = Agree; 2 = Disagree; 1 = Strongly Disagree

Table 3.

Student Response to Survey Questions Related to Career Path

All students responded “strongly agree” or “agree” to nearly all statements related to the course objectives. Only 1 survey statement garnered a “disagree” (“PHA341 prompted me to advocate for underserved populations”). Twelve of the 13 respondents are actively pursing (4), or are planning to pursue (8), an IHS pharmacy practice at some point in the future.

In addition to asking questions related to course objectives and career plans, opinions were solicited on how the PHA 341 experience shaped the way respondents view themselves as practitioners and as citizens of the world. Narrative comments in response to survey questions on the lasting impact of PHA 341 on career goals and personal/professional disposition were exceedingly positive. Respondents specifically noted the enduring impact of the Chinle immersion in shaping their views about practice and life.

DISCUSSION

PHA 341 provided several of the enrolled students with their first in-depth exposure to the Native American culture and practice opportunities within the IHS. Many who were previously unaware of the IHS practice model and the significant health care challenges faced by urban and reservation-based American Indians have actively sought additional practice experiences, and comment with passion about the lasting impact of the course experiences. This illustrates the motivational power of the learning strategies employed.

Throughout the semester, students have the chance to speak essentially one-on-one in an intimate forum with Native American tribal, spiritual, and/or health care leaders from several tribes, including Navajo, Omaha, Winnebago, Ponca, and Lakota (Sioux). In particular, the cultural immersion experience, the ability to talk openly with tribal leaders about pressing health and social issues, and the weekly structured reflection had a sustained impact on student interest, attitudes, and career direction that persisted over the course of 1-2 years. Three of the 8 fourth-professional year students who completed the course are on track for an IHS career. Nine others students who completed the course intend to pursue an IHS career upon graduation (1 student) or at some point in the future (8 students). The literature and our own experiences would predict that, if these students follow through by electing IHS advanced practice rotations, the chances of them applying for an IHS residency and ultimately electing an IHS career are good.

The PHA 341 course met essentially all of the criteria set forth by the 2001 AACP Professional Affairs Committee for a quality service-learning experience.12 Much of the course's success can be attributed to the close and continuous communication that occurred between all course planners throughout the development and implementation process. The IHS pharmacists engaged providers from all disciplines to serve as accommodation and dinner hosts and mentors to the PHA 341 students during their stay in Chinle. This gave the students the opportunity to observe how the team approach to care is strengthened through cordial social communion within the IHS complex and enriched the experience immensely. The significant contributions of the lead IHS pharmacist collaborator to meaningful student learning have been recognized by assigning him adjunct pharmacy faculty status with the School.

Because this venture was a collaborative campus-community partnership, the needs of all constituents were proactively assessed and addressed. Students were primarily interested in seeing firsthand how the IHS care model worked in actual practice, and experiencing the culture and traditions of the Diné. Almost all students were struck by the continuum of assimilation, and appreciated the opportunity to interact with Native people on both ends of the cultural spectrum, as well as those who honor both traditional and “Western” ways. The needs of community elders were attended to through housecleaning, wood chopping, basic health care assessments, etc. The students also had the opportunity to address the needs of youth through their mentorship of Chinle high school students applying for the Gates Millennium scholarships.

The IHS pharmacists also discovered that mentoring these young professionals was professionally and personally rewarding. Some claimed that sharing their love of IHS practice with the students helped them remember why they had elected this career path. The significance of this positive reinforcement is documented by the fact that, although the last Creighton alumnus working in Chinle/Tsaile recently left the area, Chinle pharmacists who are alumni of other institutions have volunteered to coordinate the 2007 immersion experience.

Students were excited about the level of pharmaceutical care they observed being practiced in the IHS pharmacies. They observed and participated in meaningful patient counseling, observed physician-pharmacist collaboration to ensure optimal patient care outcomes (including physician-initiated discussion with pharmacists on medication selection), and worked on pharmacy-sponsored projects designed to promote health and wellness in the community. By participating in elder care through the visits to those living in extreme poverty in remote areas of the reservation, the students saw the level of dedication and commitment all providers made to bringing healthcare and social services to patients who otherwise would go without. The reflections in which the students engaged, both in writing and during a 2-hour post-service immersion group discussion, illustrated that these experiences had a life-changing impact on their personal and professional minds and hearts, led to a better understanding of “caring,” and prompted a renewed sense of responsibility to advocate for underserved populations.

We are fortunate to live in a state with a rich Native American cultural heritage, and to know tribal leaders willing to talk openly with students about the historical and contemporary experiences of their people. All speakers who shared their time and wisdom with the class left a lasting impact. Student reflections and survey responses documented heightened concern relative to past and present injustices, and respect for those attempting to honor traditional ways while advancing the quality of tribal life within contemporary society. While the specific needs varied from tribe to tribe, underfunded health and social service systems, coupled with limited employment opportunities and challenged primary school systems, were commonly encountered themes. The tenacity of the tribal leaders and the determination of the care providers to address these challenges head on stimulated a sense of social responsibility in students and reminded them of their need to be vocal advocates for justice in an often unjust world.

Like others who have reported positive student reactions to service-learning experiences,23-25 PHA 341 students have expressed perceptions of professional growth in several dimensions including cultural appreciation and respect, awareness of health disparities and the need for social responsibility, appreciation for the spiritual aspect of wellness, and the positive impact of traditions on health, and a recognition of professionally rewarding practice opportunities.

As previously noted, reflection is an integral component of the PHA 341 course. Some students come to the course with significant experience in reflection and journaling while, for others, it was a relatively new experience. By the end of the semester, however, all students were writing thoughtfully about the lessons they learned from the speakers, readings, and personal experiences. A particularly poignant example from a final course evaluation is provided below, with permission from the student author.

“I learned so much watching the grandmother weave her rug, and look out the window at all that has changed. No words can describe what I learned from that. When I observed her watching the change through the window, I felt like I was passing into the future and looking back at history all at the same time. Strangely enough, it was only then that I knew I could make change in the world, even if only for a moment in time, or for a moment in someone else's time. This experience changed me. There are those rare moments where a moment will never, ever leave you. They become part of you forever as you breathe in the moment, and this was one of those moments for me. At 27, if I had to draw a line in my own timeline indicating the exact moment that I became an adult, an aspiring professional, it would be then. I watched her look at the tires that used to be horses, the sneakers that used to be moccasins, and I knew it was a moment for the both of us that would never leave. How does one express this in words? You can't.”

With several Creighton pharmacy alumni recently taking positions at IHS and tribally run facilities of the Winnebago and Omaha nations, respectively, the PHA 341 faculty members are investigating expanding the course to incorporate immersions on these nearby reservations. Unlike Chinle, the pharmacists who serve these communities do not live there, so alternate mechanisms to allow students to become engaged with the people outside of the hospital or clinic are being explored. The relationships built with tribal leaders may assist us in finding host families on these reservations, or reservation housing where the students can live for the week may be available for rent. Creighton faculty members could easily serve as onsite mentors in the evenings for students living and working with the Winnebago/Omaha. Creighton pharmacy alumni practicing in these Native communities have expressed interest in becoming involved.

The complete cost of running the course with a student enrollment of 4 is approximately $5,000, and securing funding is a never-ending challenge. For the past 3 years the faculty have been able to fully support student travel to Chinle through grants obtained from the Midwest Consortium for Service Learning in Higher Education and from an internal Cardoner program, which funded projects related to vocation. The awards have paid for student airfare and car rental, plus provided some assistance in covering the modest stipends offered to all Native speakers. Faculty travel, guest speaker travel reimbursement and lunches, and the balance of the stipend expenses were covered with University funds. The course faculty members believe it essential that the course be available to all students who have a sincere interest in this area of practice, regardless of their ability to pay for a fall-break immersion trip, and they will continue to seek support to defray the cost of student participation. While the Chinle immersion opportunity will be retained, the planned expansion to the Winnebago and Omaha reservations should moderate the cost per student, as there will be no need for airline tickets or rental cars. Funds to defray the cost of housing and food for students serving in these communities will be investigated through the state's rural AHEC program, which has some discretionary monies available to support students working on projects to improve health in underserved communities.

SUMMARY

Creighton's pharmacy elective on Native American culture and health meets essentially all of the criteria for a quality service-learning experience articulated by the 2001 AACP Professional Affairs Committee.12 The course has had a significant impact in shaping student awareness of the health challenges and barriers to care faced by Native American communities, and heightened the sense of personal and professional responsibility to contribute to workable solutions. A high percentage of PHA 341 alumni have proactively sought additional learning experiences with tribal people, and at least 4 are on track for IHS careers, with 8 more IHS careers anticipated. The return on investment in terms of fostering a sustained interest in IHS practice has been high, and our goal is to expand the offering to allow larger numbers of students to learn about Native culture and the personal and professional rewards of practice within tribal communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Midwest Consortium for Service Learning in Higher Education and the Cardoner at Creighton vFellows grant program. 2006 Creighton pharmacy graduates Melissa Beery, Lisa Brennan, Kelly Coughran, and Stacy Irlbeck are acknowledged for their significant contributions to the development of the PHA 341 course. Lieutenant Nicole Bruxvoort, PharmD, is acknowledged for her outstanding work as the onsite coordinator for the 2006 Chinle immersion. Fr. Raymond Bucko, Director of the Creighton Native American Studies Program, is acknowledged for his contributions to PHA 341. The authors are truly indebted to our American Indian friends, their families, and all of the individuals who opened their homes, lives, and culture for this life- and career-changing experience. Mitakuye oyasin.

Appendix 1. Selected PHA 341 reflection questions by lesson topic

Religion and healing in Native American culture: How do you react to the idea that disease is caused by a disconnect between the ill person and his/her environment, either through wounded relationships, misbehaviors or malevolence by others? What opportunities and challenges do you foresee in working with patients who subscribe to this theory of illness?

Contemporary Native issues and culture: Do you feel you are walking on the red road? What challenges do you currently face in maintaining the balance that epitomizes the red road journey through life? How do you listen for, or recognize, the signs that warn of imbalance and/or keep you centered on what's important?

IHS pharmacy practice: What did you learn about pharmacy practice in an IHS/tribal facility that excited or enticed you? What aspects of this practice prompt an uncertain or negative reaction? On average IHS pharmacists stay at an IHS facility for 2-4 years. Why do you think that is so? What impact might that have on patient care? On the community in general?

Tribal healthcare issues: The clinic physician spoke about the frustration of wanting to provide patients with appropriate health care but being hampered by various factors (e.g., patient's beliefs/culture, their lack of money for prescription medications, insufficient clinic funding, etc.) What was your reaction to her presentation? How would you try to help your patients as a pharmacist working in this clinic?

Social issues faced by urban American Indians: Our speaker shared a very personal story about her father choosing to live life on the streets. How did her story, and way she is dealing with her family situation, make you feel? How would you respond to/help her dad if he came to your pharmacy with a prescription?

Traditional Dance, Song and Spirituality: Our speakers spoke very openly about troublesome social issues facing Native people. What were your reactions to their comments, and to their expressed hope that Creighton pharmacy graduates will help meet the health needs of their people?

REFERENCES

- 1.Murawski MM, Murawski D, Wilson M. Service-learning and pharmaceutical education: An exploratory survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:160–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters SJ, MacKinnon GE., III Introductory practice and service learning experiences in U.S. pharmacy curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deselle SP, Surratt CK, Astle J, et al. Evolution of a required service-learning course: Lessons learned and plans for the future. J Pharm Teach. 2005;12:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickman NA. (Re)Learning to care: Use of service-learning as an early professionalization experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 1998;62:380–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nemire RE, Margulis L, Frenzel-Shepherd E. Prescription for a healthy service learning course: A Focus on the partnership. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 28. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamsam GD. Development of a service-learning program. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:41–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barner JC. Implementing service-learning in the pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:260–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward CT, Nemire RE, Daniel KP. The development and assessment of a medical mission elective course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69 Article 50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surratt CK, Desselle SP. The neuroscience behind drugs of abuse: A PharmD service-learning project. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drab S, Lamsam GD, Connor S, DeYoung M, Steinmetz K, Herbert M. Incorporation of service-learning across four years of the PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby B. Service-learning in today's higher education. In: Jacoby B, editor. Service-Learning in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1996. p. 5. Associates, [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandt BF. Chair report for the Professional Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Ed. 2001;65:19S–25S. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tresolini CP & the Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health professions education and relationship-centered care. Pew Health Professions Commission, 1994.

- 14.Schumann W, Moxley DP, Vanderwill W. Integrating service and reflection in the professional development of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Service-Learning. Outcomes, Reflection and Assessment. Campus Compact. Available at http://www.compact.org/disciplines/reflection/outcomes. Accessed December 1, 2006.

- 16.Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. Maintaining our commitment to change. Am J Pharm Educ. 1996;60:378–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beardsley RS. Chair report of the APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task Force on Professionalization: Enhancing professionalism in pharmacy education and practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 1996;60:26S–28S. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalmers RK, Grotpeter JJ, Hollenbeck RG, Nickman NA, Wincor MZ, Loacker G, Meyer SM. Ability-based outcome goals for the professional curriculum: A report of the Focus Group on Liberalization of the Professional Curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 1992;56:304–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The AACP Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Advisory Panel on Educational Outcomes, 1998. Available at http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/ForDeans/5763_CAPEoutcomes.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2006.

- 20.Kearney KR. Service-learning in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Adopted January 15, 2006. Available at http://www.acpe-accredit.org. Accessed December 1, 2006.

- 22.Brown SR, Birnbaum B. Student and resident education and rural practice in the Southwest Indian Health Service: A physician survey. Fam Med. 2005;37:701–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen GM, Royeen CB. Improved rural access to care: Dimensions of best practice. J Interprof Care. 2002;16:117–28. doi: 10.1080/13561820220124139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piper B, DeYoung M, Lamsam GD. Student perceptions of a service-learning experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:159–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barner JC. First-year pharmacy students' perceptions of their service-learning experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:266–71. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kearney KR. Students' self-assessment of learning through service-learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charles G, Bainbridge L, Copeman-Stewart K, Art ST, Kassam R. The interprofessional rural program of British Columbia (IRPbc) J Interprof Care. 2006;20:40–50. doi: 10.1080/13561820500498154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scammon DL, Williams SC, Li LB. Understanding physicians' decisions to practice in rural areas as a basis for developing recruitment and retention strategies. J Ambul Care Marketing. 1994;5:85–100. doi: 10.1300/j273v05n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]