Abstract

The postnatal development of the mouse is characterized by a stress hypo-responsive period (SHRP), where basal corticosterone levels are low and responsiveness to mild stressors is reduced. Maternal separation is able to disrupt the SHRP and is widely used to model early trauma. In this study we aimed at identifying of brain systems involved in acute and possible long-term effects of maternal separation. We conducted a microarray-based gene expression analysis in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus after maternal separation, which revealed 52 differentially regulated genes compared to undisturbed controls, among them are 37 up-regulated and 15 down-regulated genes. One of the prominently up-regulated genes, angiotensinogen, was validated using in-situ hybridization. Angiotensinogen is the precursor of angiotensin II, the main effector of the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which is known to be involved in stress system modulation in adult animals. Using the selective angiotensin type I receptor [AT(1)] antagonist candesartan we found strong effects on CRH and GR mRNA expression in the brain and ACTH release following maternal separation. AT(1) receptor blockade appears to enhance central effects of maternal separation in the neonate, suggesting a suppressing function of brain RAS during the SHRP. Taken together, our results illustrate the molecular adaptations that occur in the paraventricular nucleus following maternal separation and contribute to identifying signaling cascades that control stress system activity in the neonate.

Keywords: postnatal, stress hypo-responsive period, mouse, maternal separation, paraventricular nucleus, microarray, renin-angiotensin system, candesartan

Introduction

During ontogeny the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis undergoes a period of quiescence (Levine et al., 1967; Schapiro et al., 1962). This so-called stress hypo-responsive period (SHRP), which in the mouse lasts from about postnatal day 1 to postnatal day 12 (Schmidt et al., 2003a), is characterized by low basal corticosterone levels and a decreased responsiveness to a variety of stressors (Cirulli et al., 1992; Rosenfeld et al., 1992; Schmidt et al., 2002b).

Although suppressed in response, the stress system of the neonate is still capable to respond to more severe and possibly life threatening challenges, as e.g. exposure to cold or ether fumes (Schoenfeld et al., 1980; Walker and Dallman, 1993; Walker et al., 1991). A profound activation of the HPA axis occurs following prolonged separation of maternal signals, which not only increases basal corticosterone levels, but also enhances the responsiveness of the stress system to mild challenges (Levine, 2001; Schmidt et al., 2004).

Disruption of the SHRP, which has also been postulated to exist to some extent in humans (Gunnar, 1998; Gunnar and Donzella, 2002), has been shown to result in numerous long-lasting behavioral and neuroendocrine consequences in both humans and animals (Bernet and Stein, 1999; Heim et al., 2000, 2002; Plotsky et al., 2005; Weaver et al., 2004). While most of the earlier work was performed in rats, many recent studies studied early life stress paradigms using mice (Cruz et al., 2008; Kawakami et al., 2007; Macri and Laviola, 2004; Marco et al., 2009; Ognibene et al., 2008; Rice et al., 2008). However, due to the wide variability of postnatal manipulations, species and strain differences, the data on the long-term effects of early life stress are often inconsistent. For instance, while many authors have shown an increased anxiety after postnatal stress (Veenema et al., 2008), other reports show no clear phenotype (Millstein and Holmes, 2007) or even a decreased anxiety (Fabricius et al., 2008). One of the main problems in understanding these different outcomes is the lack of knowledge about the acute effects of the different postnatal stress paradigms.

The mechanism of HPA axis regulation during the SHRP is intriguing, as it may explain possible regulatory pathways in the adult animals. We could recently show that an apparently enhanced glucocorticoid receptor-mediated feedback plays an essential role in maintaining low stress responsiveness in the neonate (Schmidt et al., 2005, 2009). Metabolic signals, which are altered due to maternal separation, activate the arcuate nucleus and seem to overcome this GR blockade via an CRH-mediated central pathway (Schmidt et al., 2006a,b). In addition, maternal signals as licking and grooming have been identified as essential parameters to ensure low HPA-system activity (Suchecki et al., 1993; van Oers et al., 1998).

Most of the current knowledge about the HPA axis regulation in the neonate is thus based on hypothesis-driven approaches. However, additional, so far uninvestigated brain systems are likely to contribute to the acute and long-term effects of maternal separation and early trauma. In the current study we therefore addressed this question by performing a microarray-based gene expression analysis of maternally separated and non-separated mouse pups. We selected the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) as a main region of interest, as most of the acute gene expression changes due to maternal separation have so far been reported for this brain structure. Based on a gene expression profiling approach we are able to identify and functionally validate the brain renin-angiotensin system as a modulator of stress system function during the SHRP.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The offspring of 3-month-old C57Bl6/N mice (obtained from Charles River) was used in this study. After a habituation period of 1 week, two females were mated with one male in standard mouse polycarbonate cages (45 × 25 × 20 cm) containing sawdust bedding. Pregnant females were single housed and transferred to clean polycarbonate cages containing sawdust and two sheets of paper towels for nest material during the last week of gestation. Pregnant females were checked for litters daily between 9 and 10 a.m. If litters were found, the day of birth was defined as day 0 for that litter. On the day after parturition, day 1, each litter was culled to eight healthy pups (four males and four females) and remained undisturbed until used in the experiment. All animals were housed under a 12L:12D cycle (lights on at 6 a.m.) and constant temperature (23 ± 2°C) and humidity (55 ± 5%) conditions. Food and water was provided ad libitum.

The experiments were carried out in accordance with European Communities Council Directive 86/609/EEC. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering during the experiments. The protocols were approved by the committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Government of Upper Bavaria, Germany.

Experimental design

Experiment 1: gene expression profile

A total of 6 litters were used in the study. Litters were randomly assigned to either a maternally non-separated or 24-h maternally separated condition. All pups from a litter were sacrificed by decapitation and trunk blood was collected immediately after the 24-h deprivation period or – in the case of the control litters – immediately after separation from the mother on postnatal day 9.

Experiment 2: functional validation

A total of 8 litters were used in the study. Each nest was assigned randomly to one of the two conditions, 8-h maternal separation or non-separated control. Pups in each litter were either treated subcutaneously with vehicle (saline) or 1 mg/kg of the angiotensin type I receptor AT(1) antagonist candesartan (provided by AstraZeneca, Wedel, Germany) 2 h after the onset of separation (6 h before testing). The dosage of the drug was based on literature reports (Armando et al., 2007; Fan et al., 2004) and it has been demonstrated that candesartan crosses the blood-brain barrier (Pavel et al., 2008). The injection volume was 30 μl. At the time of testing, all pups from a litter were sacrificed by decapitation.

Maternal separation

Maternal separation took place in a separate room in the animal facility under similar light and temperature conditions as mentioned previously. The initiation day of maternal separation for all experiments was postnatal day 8. If a nest was assigned to maternal separation, mothers were removed from their home cages between 8 and 10 a.m. The home cage, containing the litter, was then placed on a heating pad maintained at 30–33°C. Neither food nor water was available during the separation period. In experiment 1, separation lasted for 24 h. In experiment 2, pups were only separated for 8 h, in order to assess the role of the brain renin-angiotensin system in activating the HPA axis. The 8-h time-point was chosen based on earlier studies, which indicated a full activation of the HPA axis during the first 8 h of separation (Schmidt et al., 2004).

Sampling procedure

Trunk blood from all pups was collected individually in labeled 1.5 ml EDTA-coated microcentrifuge tubes. All blood samples were kept on ice and later centrifuged for 15 min at 6000 rpm at 4°C. Plasma was transferred to clean, labeled 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. All plasma samples were stored frozen at −20°C until the determination of corticosterone (experiments 1 and 2) and ACTH (experiment 2). ACTH and corticosterone were measured by RIA (MP Biomedicals Inc.; sensitivity 10 pg/ml and 6.25 ng/ml, respectively). Whole heads (without skin and jaw) were removed, frozen in isopropane and stored at −80°C for microarray analysis or in-situ hybridization.

Microarray procedure

The brains of six animals per group were used. Frozen brains were sectioned at −20°C in a cryostat microtome at 100 μm in the coronal plane through the level of the hypothalamic PVN. The sections were mounted on superfrost plus slides (Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany) and tissue micropunches were taken using a sample corer of 1 mm diameter (Fine Science Tools, Heidelberg, Germany). The PVNs of two animals from the same group were pooled into one sample, giving a total of three samples for each treatment. Punches were immediately transferred to frozen 1.5 ml plastic tubes and stored ad −80°C until RNA isolation. The accuracy of the punch was controlled by cresyl violet counterstaining of the punched sections and confirming the punch location under a light microscope.

Total RNA of the punched tissue was isolated with the Trizol (Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) method following the manufacturers’ protocol. Isolated RNA was then amplified in one round using the Ambion Amino Allyl MessageAmp aRNA kit (Ambion, Huntingdon, UK). RNA samples were quantified by spectrophotometry and RNA integrity checked on 1% agarose gels using a deionized formamide-based loading buffer. Equal amounts of total aRNA were pooled to one “non-separated” and one “separated” sample containing 40 μg of aRNA each and dye coupled using indirect labeling. To exclude dye bias, one-half of each sample was coupled to cyanine 3 (Cy3) and the other one-half to cyanine 5 (Cy5). The pooled samples were hybridized on five Max-Planck Institute 24 k mouse cDNA arrays (Max-Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Munich, Germany) for each dye coupling combination (10 arrays total) and scanned on a PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Rodgau-Jügesheim, Germany) ScanArray 4000 laser scanner as described previously (Deussing et al., 2007).

In-situ hybridization

The brains of eight animals per group were used for in-situ hybridization (different animals than used for microarray analysis). Frozen brains were sectioned at −20°C in a cryostat microtome at 16 μm in the coronal plane through the level of the hypothalamic PVN. The sections were thaw-mounted on superfrost plus slides (Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany), dried and kept at −80°C. In-situ hybridization using 35S UTP labeled ribonucleotide probes were performed as described previously (Schmidt et al., 2002a). For angiotensinogen, riboprobe synthesis was carried out from a mouse brain cDNA library, yielding a 711 bp long probe (nucleotides GGATACAC + 703 of accession no NM007428). The riboprobes for corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) were described previously (Schmidt et al., 2003b). The slides were apposed to Kodak Biomax MR film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY, USA) and developed. Autoradiographs were digitized, and relative expression was determined by computer-assisted optical densitometry (Scion Image, Scion Corporation). The mean of four measurements was calculated from each animal.

Data analysis

The microarray data were quantified using the fixed circle quantification method of QuantArray (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and a nonlinear regression method (Yang et al., 2002) implemented in the statistical software R1. To correct for multiple testing, p-values were adjusted following the false discovery rate (FDR) method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). An adjusted p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Differentially expressed genes were imported into the BiblioSphere software V 7.20 (Genomatix, Munich, Germany) and assigned to Gene Ontology categories to identify their biological function.

For the in-situ hybridization and endocrine data, the results were analyzed by analysis of variance procedures (ANOVA) with the level of significance set at p < 0.05. The initial analysis included sex as a factor; once it was determined that sex was not a significant factor, the data were collapsed across this variable. Where appropriate, tests of simple main and interaction effects were made with the Mann–Whitney–U test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Experiment 1: gene expression profile

Endocrine validation

To validate the success of the maternal deprivation procedure, plasma corticosterone was measured. As expected, maternal separation resulted in a significant increase of circulating corticosterone (non-separated: 6.65 ± 1.64 ng/ml; separated: 109.01 ± 7.95 ng/ml; p < 0.05).

Microarray results

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBIs Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)2 and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE14687. For the microarray analysis only genes with a fold-regulation of 1.5 or higher and an adjusted p-value of less than 0.05 were regarded as differentially regulated. Using these cut-off criteria, we identified 52 differentially expressed genes. Of these genes, 37 were up-regulated in the maternally separated group (see Table 1), while 15 genes were down-regulated (see Table 2). Maternal separation affected the expression of genes involved in various different functions, including apoptosis, metabolic processes, signal transduction, cell-cell interaction, gene expression, development, cellular transport or proliferation. For the current study, we chose to focus on the involvement of the angiotensinogen gene (AGT) in maternal separation for further validation and follow-up studies. The up-regulation of AGT in separated animals suggested a functional role of the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in regulating the response to maternal separation. This system has previously been indicated to be involved in stress system regulation and dysregulation in adulthood (Armando et al., 2001, 2007; Plotsky et al., 1988; Raasch et al., 2006). In addition, genetic variation in genes involved in the brain RAS have been linked to disorders as unipolar depression or panic disorder (Baghai et al., 2006; Olsson et al., 2004). However, few data on the involvement of the brain RAS in regulating the HPA axis during ontogeny are available.

Table 1.

List of significantly up-regulated genes in the PVN region of the hypothalamus in 9-day-old maternally separated mouse pups compared to controls.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Function | Accession number | Fold regulation | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rap2ip | Rap2 interacting protein | Signal transduction | AI839996 | 2.6876 | 0.0048 |

| BC055107 | BC055107 | Unknown | AI836637 | 2.4745 | 0.0027 |

| Gjb6 | Gap junction membrane channel protein beta 6 | Development | AI847389 | 2.3288 | 0.0027 |

| DAP-3 | Disks large-associated protein 3 | Cell-cell signalling | AI850878 | 2.2489 | 0.0267 |

| NA | NA | Unknown | AI854246 | 2.1465 | 0.0019 |

| 2610304G08Rik | RIKEN cDNA 2610304G08 gene | Unknown | AI843346 | 2.0788 | 0.0073 |

| Ttf2 | Transcription termination factor, RNA polymerase II | Gene expression | AA473992 | 2.0507 | 0.0197 |

| Paqr8 | Progestin and adipoQ receptor family member VIII | Unknown | AI843077 | 1.9711 | 0.0224 |

| Agt | Angiotensinogen | Signal transduction | AI838902 | 1.934 | 0.028 |

| Hipk3 | Homeodomain interacting protein kinase 3 | Apoptosis | AI449703 | 1.9338 | 0.0338 |

| Atp1a2 | ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 2 polypeptide | Cell-cell signalling | AI851097 | 1.8715 | 0.0278 |

| Glul | Glutamate-ammonia ligase (glutamine synthase) | Metabolic processes | AI835674 | 1.8393 | 0.0003 |

| Sqrdl | Sulfide quinone reductase-like (yeast) | Metabolic processes | AA473822 | 1.8204 | 0.0201 |

| Olah | Oleoyl-ACP hydrolase | Metabolic processes | AI414810 | 1.775 | 0.0246 |

| Cln8 | Ceroid-lipofuscinosis, neuronal 8 | Apoptosis | AI843820 | 1.7421 | 0.036 |

| Ipw | Imprinted gene in the Prader-Willi syndrome region | Unknown | AI852618 | 1.7417 | 0.0355 |

| Purb | Purine rich element binding protein B | Apoptosis | AI854464 | 1.7187 | 0.0005 |

| NA | Transcribed sequence | Unknown | AI413315 | 1.71 | 0.0012 |

| Aldo3 | Aldolase 3, C isoform | Metabolic processes | AI841101 | 1.7039 | 0.0044 |

| Ddx3y | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 3, Y-linked | Transcription | AI448347 | 1.698 | 0.0135 |

| Mapre2 | Microtubule-associated protein, RP/EB family, member 2 | Cellular structure | AI227140 | 1.6343 | 0.0022 |

| 1110018M03Rik | RIKEN cDNA 1110018M03 gene | Unknown | AI854593 | 1.6336 | 0.0475 |

| Sparc | Secreted acidic cysteine rich glycoprotein | Signal transduction | AI840232 | 1.6115 | 0.0081 |

| 2210013O21Rik | RIKEN cDNA 2210013021 gene | Unknown | AI846437 | 1.5878 | 0.0182 |

| Slc24a2 | Solute carrier family 24, member 2 | Transport | AI847460 | 1.5781 | 0.0355 |

| Scn2b | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, beta | Transport | AI840361 | 1.5585 | 0.0035 |

| Map4k4 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 4 | Signal transduction | AI465256 | 1.5571 | 0.0427 |

| I125 | Interleukin 25 | Signal transduction | W71193 | 1.5411 | 0.0083 |

| Cfdp | Craniofacial development protein 1 | Apoptosis | AI225952 | 1.54 | 0.0062 |

| Xpa | Xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group A | Apoptosis | AI838722 | 1.5375 | 0.0101 |

| Mt1 | Metallothionein 1 | Signal transduction | AI427514 | 1.525 | 0.012 |

| 0610007C21Rik | RIKEN cDNA 0610007C21 gene | Unknown | AI837774 | 1.5166 | 0.0221 |

| Tmeml30 | Transmembrane protein 130 | Unknown | AI854455 | 1.5158 | 0.0041 |

| Gas5 | Growth arrest specific 5 | Apoptosis | AI848205 | 1.5123 | 0.0044 |

| Gtl2 | GTL2, imprinted maternally expressed untranslated mRNA | Proliferation | AI847231 | 1.5118 | 0.0022 |

| Clstn3 | Calsyntenin 3 | Cell-cell signalling | AI851951 | 1.5075 | 0.0355 |

| Lmna | Lamin A | Cellular structure | AI845319 | 1.5062 | 0.0224 |

Table 2.

List of significantly down-regulated genes in the PVN region of the hypothalamus in 9-day-old maternally separated mouse pups compared to controls.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Function | Accession number | Fold regulation | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xist | Inactive X specific transcripts | Gene expression | AI227127 | −2.1304 | 0.0062 |

| Dcpp | Demilune cell and parotid protein | Development | AA036082 | −2.1191 | 0.0345 |

| NA | 13 days embryo heart cDNA | Unknown | AA259358 | −1.7566 | 0.0313 |

| St8sia4 | ST8 alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminide alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase 4 | Metabolic processes | AI385627 | −1.6858 | 0.0355 |

| Hmgcs1 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A synthase 1 | Metabolic processes | AI841574 | −1.6697 | 0.0009 |

| Sfrs11 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 11 | Apoptosis | AI465457 | −1.6512 | 0.0056 |

| Syt4 | Synaptotagmin 4 | Cell-cell signalling | AI843967 | −1.6253 | 0.0201 |

| NA | Transcribed sequences | Unknown | AI839136 | −1.6099 | 0.0452 |

| NA | 7 days neonate cerebellum cDNA, clone:A730008E19 | Unknown | W78304 | −1.5498 | 0.0292 |

| Slurp1 | Secreted Ly6/Plaur domain containing 1 | Metabolic processes | AI415082 | −1.5308 | 0.0278 |

| Rtn3 | Reticulon 3 | Apoptosis | AI852459 | −1.5302 | 0.013 |

| Mtap1b | Microtubule-associated protein 1 B | Development | AI852731 | −1.5183 | 0.0104 |

| Tcf712 | Transcription factor 7-like 2, T-cell specific, HMG-box | Gene expression | AI451561 | −1.516 | 0.0131 |

| B230208H17Rik | RIKEN cDNA B230208H17 gene | Unknown | AI835464 | −1.5151 | 0.0337 |

| Zfp535 | Zinc finger protein 535 | Unknown | AA272875 | −1.5089 | 0.0421 |

Validation by in-situ hybridization

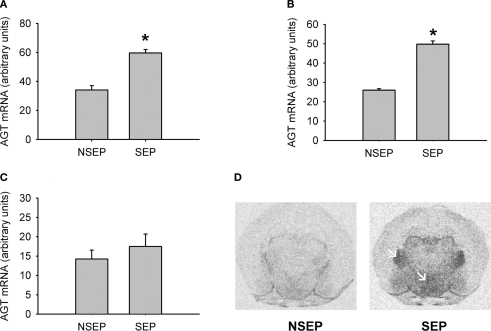

In-situ hybridization was used to independently verify the results from the previous microarray analysis as well as to determine brain expression and distribution of the regulated gene. The results are shown in Figure 1. Under basal condition, we observed a weak expression of AGT in hypothalamic and thalamic nuclei, with little or no expression in cortical or limbic brain structures (Figure 1D). Following maternal separation angiotensinogen expression was significantly up-regulated in the hypothalamus (MWU: p < 0.01). In addition, an up-regulation of this gene could also be demonstrated in the ventral thalamic nucleus (MWU: p < 0.01). No significant regulation of AGT was found in the cortex (MWU: p < 0.421).

Figure 1.

Validation of expression changes of angiotensinogen by in-situ hybridization. A significant up-regulation of angiotensinogen was found in the PVN (A) and the ventral thalamic nucleus (B). No significant expression differences were observed in the cortex (C). Figure (D) shows representative autoradiograph pictures of angiotensinogen mRNA expression in maternally non-separated (NSEP) and maternally separated (SEP) animals. Left arrow: ventral thalamic nucleus; right arrow: paraventricular nucleus. *Significant from NSEP, n = 6 per group.

Experiment 2: functional validation

In order to address a possible functional consequence of the differential regulation of AGT, the role of the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in modulating maternal separation was addressed. For this experiment we chose to separate the animals for a shorter time period, to examine the involvement of the brain RAS in the activation of the HPA axis due to maternal separation. In previous studies we could show, that the activation of the stress system occurs during the first 8 h of maternal separation (Schmidt et al., 2004). Two hours after the onset of the separation period, animals received an injection of either the AT(1) receptor antagonist candesartan or vehicle (saline). For corticosterone, ANOVA revealed a significant effect of condition [F(1,60) = 347.077 (p < 0.0001)], but not for treatment [F(1,60) = 0.499 (p < 0.5)]. Maternal separation resulted in a robust increase in corticosterone secretion (Figure 2A). This effect was not different between the two treatment groups. For ACTH, ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition [F(1,60) = 89.59 (p < 0.0001)] and treatment [F(1,60) = 54.018 (p < 0.0001)], as well as an interaction of condition and treatment [F(1,60) = 32.406 (p < 0.0001)]. Maternal separation increased ACTH plasma levels compared to non-separated controls. This increase was significantly higher in candesartan-treated pups compared to vehicle-treated deprived pups (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of candesartan treatment in non-separated (NSEP) and separated (SEP) mouse pups on corticosterone (A) and ACTH (B) plasma values. Maternal separation increased corticosterone and ACTH secretion. No effects of candesartan treatment were seen for corticosterone. For ACTH, candesartan treatment resulted in a significant increase of ACTH secretion compared to vehicle-treated pups of the same condition. *Significant from NSEP, #significant from vehicle treatment, n = 16 per group.

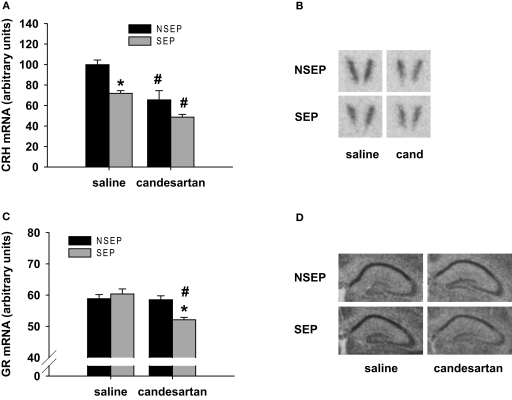

For the CRH mRNA expression in the PVN, ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition [F(1,27) = 14.15 (p < 0.001)] and treatment [F(1,27) = 23.404 (p < 0.0001)]. Maternal separation resulted in a decrease of CRH mRNA expression in the PVN in vehicle-treated animals (Figures 3A and B). This effect was mimicked by candesartan treatment in non-separated pups, resulting in significantly lower CRH mRNA expression levels compared to vehicle controls. The lowest CRH mRNA expression was observed in maternally separated animals, which received a candesartan treatment 6 h before testing.

Figure 3.

Effects of candesartan treatment in non-separated (NSEP) and separated (SEP) mouse pups on CRH mRNA expression (A) in the PVN and GR mRNA expression (C) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. CRH mRNA expression was significantly decreased by maternal separation and candesartan treatment. The lowest expression of CRH was observed in candesartan-treated, separated mouse pups. GR expression was not affected by maternal separation or candesartan treatment. However, when combined we observed a significant down-regulation of GR mRNA expression. (B) and (D): Representative autoradiograms of CRH mRNA expression in the PVN and GR mRNA expression in the hippocampus, respectively. *Significant from NSEP, #significant from vehicle treatment, n = 8 per group.

GR mRNA expression was measured in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment [F(1,27) = 11.75 (p < 0.01)], as well as an interaction of condition and treatment [F(1,27) = 9.951 (p < 0.01)]. In vehicle-treated animals, GR mRNA expression was not altered by 8 h of maternal separation. Candesartan treatment of non-separated pups did also not alter GR mRNA expression. However, maternally separated pups, which were treated with candesartan, showed a significantly decreased GR mRNA expression compared to saline treated, separated pups as well as compared to non-separated, candesartan-treated pups (Figures 3C and D).

Discussion

Early trauma has been shown to result in lasting consequences and an increased risk for a number of diseases, including psychiatric disorders (Chapman et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2004; Heim et al., 2008). The mechanism by which trauma affects health is so far not understood completely.

To study the underlying molecular mechanisms that lead to disease, animal models as maternal separation have been used to model early traumatic events. Numerous groups have shown that the paradigm of maternal separation results in long-lasting neuroendocrine and behavioral consequences, thereby mimicking the human situation of early trauma (Ladd et al., 1996; Macri and Laviola, 2004; Oitzl et al., 2000; Rots et al., 1996; Suchecki et al., 2000; Sutanto et al., 1996; Workel et al., 2001). In the current study, we examined gene expression changes which occur as a direct consequence of a single 24-h maternal separation period in order to identify signal cascades and brain systems that are regulated by maternal separation. This specific paradigm was chosen as the single separation episode is clearly defined in time and issues of adaptation to the separation can be avoided (Enthoven et al., 2008). We focused on the area of the hypothalamic PVN, as this brain region plays a key role in regulating HPA axis activity. Our unbiased, microarray-based approach resulted in the identification of 52 differentially regulated genes. The majority of the regulated genes were found to be up-regulated (37), while only 15 genes were down-regulated as a consequence of maternal separation.

One of the highest regulated genes was the angiotensinogen gene, which we independently validated by in-situ hybridization. Angiotensinogen is the precursor of angiotensin I that in turn is transformed into angiotensin II which is the primary effector of the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS). First postulated in 1971 (Ganten et al., 1971), the main functions of the brain RAS are regulation of fluid electrolyte homeostasis and modulation of cardiovascular responses (Johnson and Thunhorst, 1997; Phillips and Sumners, 1998). However, this brain system has also been implicated in the regulation of memory, cognition, addiction as well as stress system regulation and has been associated with mood disorders (Belcheva et al., 2000; Saab et al., 2007; Saavedra et al., 2004). We therefore chose to further investigate, whether the activation of angiotensinogen after maternal separation might be of a functional consequence for the function of the stress system in the neonate. For the pharmacological validation of the involvement of angiotensinogen in modulating HPA axis activity we focused on the first 8 h of the separation period, as we have previously shown that activation occurs during this time (Schmidt et al., 2004).

We found robust changes in ACTH release following application of the AT(1) receptor antagonist candesartan in maternally separated animals. This change in ACTH release was not reflected in the corticosterone secretion at that time point. There are various possible explanations for this phenomenon. Numerous reports indicate that activation of AT(1) receptors increases corticosterone release from the adrenal cortex (Aguilar et al., 2004; Nithipatikom et al., 2005). This mechanism might also be involved in increasing adrenal sensitivity and adrenal corticosterone secretion during maternal separation. Alternatively this effect might be due to a contributing impact of the AT(2) receptor. Blockade of the AT(1) receptor results in increased circulating angiotensin II (Campbell, 1996), which is in turn stimulating the AT(2) receptor (Siragy and Carey, 2000). Blockade of AT(1) receptors with candesartan might thus on one hand activate the central part of the HPA axis, but block corticosterone release at the adrenal level. Alternatively, high ACTH levels at the time of testing could result in a higher corticosterone secretion at later time points.

In the brain, candesartan treatment in non-separated mouse pups mimicked the effects of maternal separation. CRH mRNA expression was equally decreased after maternal separation and candesartan treatment. This finding is intriguing, as the decrease of CRH expression following maternal separation remains a puzzling phenomenon. Our data indicate that the brain RAS might be directly involved in regulation of CRH mRNA expression in the neonate, independent of peripheral corticosterone concentrations. These data are in line with reports in adult animals, where angiotensin II was found to increase CRH mRNA expression in the PVN, an area where predominantly the AT(1) receptor is expressed (Sumitomo et al., 1991). Further, a blockade of AT(1) receptors seemed to exponentiate the central effects of maternal separation. The lowest expression levels of CRH mRNA in the PVN were found in candesartan-treated, maternally separated animals. In this group we also detected a decrease in GR mRNA in the hippocampus, a process that normally occurs only at longer separation periods (Schmidt et al., 2004). These data are in contrast to the adult situation, where the brain RAS has mostly been found to activate the stress system (Saavedra and Benicky, 2007), suggesting a different role of the brain RAS in the developing brain. This hypothesis is further supported by the different AT(1) receptor distribution during development and adulthood (Millan et al., 1991; Nuyt et al., 2001; Shanmugam et al., 1995).

Angiotensinogen is a precursor protein for a number of different cleavage products that act on at least four different angiotensin receptors in the brain (Phillips and de Oliveira, 2008). While in the current manuscript we observed a clear effect by blocking the AT(1) receptor, an additional involvement of the AT(2) or AT(4) receptors can not be excluded. Both receptors are expressed in the PVN (von Bohlen und Halbach and Albrecht, 2006). While treatment with an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor should have similar effects compared to candesartan treatment, additional studies using specific AT(2) or AT(4) antagonists are needed to unravel the role of these receptors in the effects of maternal deprivation.

As different postnatal stress paradigms, including 24-h maternal separation, have long-lasting physiological and behavioral consequences, it is intriguing to speculate which role the brain RAS might play in these effects. On one hand, early life stress effects could lastingly affect the function of the brain RAS, thereby influencing the development or the adult reactivity of the stress system. On the other hand, the lasting effects of early life stress could be dependent on specific genetic risk alleles, similar to e.g. the serotonin transporter or the CRH receptor type 1 (Bradley et al., 2008; Caspi et al., 2003). However, while polymorphisms in the brain RAS have been linked to depression and bipolar disorder (Meira-Lima et al., 2000; Saab et al., 2007), we are not aware of any study investigating the interaction of these polymorphisms with e.g. childhood trauma.

In summary, our data indicate that during postnatal development the brain RAS functions to suppress HPA axis activity. Blockade of this system results in a central (but not peripheral) activation of the HPA axis under basal conditions and enhances the response to maternal separation. Thus, the up-regulation of angiotensinogen after maternal separation functions to suppress the separation-induced activation of the stress system.

Supplementary Material

Microarray data are accessible through http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=znizpkymesmaqrk&acc=GSE14687

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Claudia Kühne, Daniela Harbich and Stephanie Alam are gratefully acknowledged for technical assistance. AstraZeneca (Wedel, Germany) thankfully provided the candesartan used in this study. This work has been funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the framework of the National Genome Research Network (NGFN) Förderkennzeichen 01GS0481, by the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association in the framework of the Helmholtz Alliance for Mental Health in an Ageing Society (HA-215) and the Helmholtz Alliance on Systems Biology (VH-VI-252).

Footnotes

References

- Aguilar F., Lo M., Claustrat B., Saez J. M., Sassard J., Li J. Y. (2004). Hypersensitivity of the adrenal cortex to trophic and secretory effects of angiotensin II in lyon genetically-hypertensive rats. Hypertension 43, 87–93 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107194.44040.d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armando I., Carranza A., Nishimura Y., Hoe K. L., Barontini M., Terron J. A., Falcon-Neri A., Ito T., Juorio A. V., Saavedra J. M. (2001). Peripheral administration of an angiotensin II AT(1) receptor antagonist decreases the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to isolation stress. Endocrinology 142, 3880–3889 10.1210/en.142.9.3880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armando I., Volpi S., Aguilera G., Saavedra J. M. (2007). Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade prevents the hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor response to isolation stress. Brain Res. 1142, 92–99 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baghai T. C., Binder E. B., Schule C., Salyakina D., Eser D., Lucae S., Zwanzger P., Haberger C., Zill P., Ising M., Deiml T., Uhr M., Illig T., Wichmann H. E., Modell S., Nothdurfter C., Holsboer F., Muller-Myhsok B., Moller H. J., Rupprecht R., Bondy B. (2006). Polymorphisms in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene are associated with unipolar depression, ACE activity and hypercortisolism. Mol. Psychiatry 11, 1003–1015 10.1038/sj.mp.4001884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcheva I., Ternianov A., Georgiev V. (2000). Lateralized learning and memory effects of angiotensin II microinjected into the rat CA1 hippocampal area. Peptides 21, 407–411 10.1016/S0196-9781(00)00163-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Bernet C. Z., Stein M. B. (1999). Relationship of childhood maltreatment to the onset and course of major depression in adulthood. Depress. Anxiety 9, 169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R. G., Binder E. B., Epstein M. P., Tang Y., Nair H. P., Liu W., Gillespie C. F., Berg T., Evces M., Newport D. J., Stowe Z. N., Heim C. M., Nemeroff C. B., Schwartz A., Cubells J. F., Ressler K. J. (2008). Influence of child abuse on adult depression: moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65, 190–200 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D. J. (1996). Endogenous angiotensin II levels and the mechanism of action of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor type 1 antagonists. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. Suppl. 3, S125–S131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A., Sugden K., Moffitt T. E., Taylor A., Craig I. W., Harrington H., McClay J., Mill J., Martin J., Braithwaite A., Poulton R. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 301, 386–389 10.1126/science.1083968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman D. P., Whitfield C. L., Felitti V. J., Dube S. R., Edwards V. J., Anda R. F. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J. Affect. Disord. 82, 217–225 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli F., Gottlieb S. L., Rosenfeld P., Levine S. (1992). Maternal factors regulate stress responsiveness in the neonatal rat. Psychobiology 20, 143–152 [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F. C., Quadros I. M., Planeta C. D., Miczek K. A. (2008). Maternal separation stress in male mice: long-term increases in alcohol intake. Psychopharmacology 201, 459–468 10.1007/s00213-008-1307-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deussing J. M., Kühne C., Pütz B., Panhuysen M., Breu J., Stenzel-Poore M. P., Holsboer F., Wurst W. (2007). Expression profiling identifies the CRH/CRH-R1 system as a modulator of neurovascular gene activity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 1476–1495 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M., Giles W. H., Felitti V. J., Dube S. R., Williams J. E., Chapman D. P., Anda R. F. (2004). Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation 110, 1761–1766 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven L., Oitzl M. S., Koning N., van der Mark M., De Kloet E. R. (2008). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity of newborn mice rapidly desensitizes to repeated maternal absence but becomes highly responsive to novelty. Endocrinology 149, 6366–6377 10.1210/en.2008-0238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius K., Wörtwein G., Pakkenberg B. (2008). The impact of maternal separation on adult mouse behaviour and on the total neuron number in the mouse hippocampus. Brain Struct. Funct. 212, 403–416 10.1007/s00429-007-0169-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q., Liao J., Kobayashi M., Yamashita M., Gu L., Gohda T., Suzuki Y., Wang L. N., Horikoshi S., Tomino Y. (2004). Candesartan reduced advanced glycation end-products accumulation and diminished nitro-oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic KK/Ta mice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 19, 3012–3020 10.1093/ndt/gfh499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganten D., Minnich J. L., Granger P., Hayduk K., Brecht H. M., Barbeau A., Boucher R., Genest J., Johnson A. K., Thunhorst R., Phillips M. I., Sumners C. (1971). Angiotensin-forming enzyme in brain tissue. Science 173, 64–65 10.1126/science.173.3991.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M. R. (1998). Quality of early care and buffering of neuroendocrine stress reactions: potential effects on the developing human brain. Prev. Med. 27, 208–211 10.1006/pmed.1998.0276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M. R., Donzella B. (2002). Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 27, 199–220 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C., Mletzko T., Purselle D., Musselman D. L., Nemeroff C. B. (2008). The dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing factor test in men with major depression: role of childhood trauma. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 398–405 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C., Newport D. J., Miller A. H., Nemeroff C. B. (2000). Long-term neuroendocrine effects of childhood maltreatment. JAMA 284, 2321. 10.1001/jama.284.18.2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C., Newport D. J., Wagner D., Wilcox M. M., Miller A. H., Nemeroff C. B. (2002). The role of early adverse experience and adulthood stress in the prediction of neuroendocrine stress reactivity in women: a multiple regression analysis. Depress. Anxiety 15, 117–125 10.1002/da.10015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. K., Thunhorst R. L. (1997). The neuroendocrinology of thirst and salt appetite: visceral sensory signals and mechanisms of central integration Angiotensin II in central nervous system physiology. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 18, 292–353 10.1006/frne.1997.0153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami S. E., Quadros I. M. H., Takahashi S., Suchecki D. (2007). Long maternal separation accelerates behavioural sensitization to ethanol in female, but not in male mice. Behav. Brain Res. 184, 109–116 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd C. O., Owens M. J., Nemeroff C. B. (1996). Persistent changes in corticotropin-releasing factor neuronal systems induced by maternal deprivation. Endocrinology 137, 1212–1218 10.1210/en.137.4.1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. (2001). Primary social relationships influence the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the rat. Physiol. Behav. 73, 255–260 10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00496-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S., Glick D., Nakane P. K. (1967). Adrenal and plasma corticosterone and vitamin A in rat adrenal glands during postnatal development. Endocrinology 80, 910–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macri S., Laviola G. (2004). Single episode of maternal deprivation and adult depressive profile in mice: interaction with cannabinoid exposure during adolescence. Behav. Brain Res. 154, 231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco E. M., Adriani W., Llorente R., Laviola G., Viveros M. P. (2009). Detrimental psychophysiological effects of early maternal deprivation in adolescent and adult rodents: altered responses to cannabinoid exposure. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 498–507 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meira-Lima I. V., Pereira A. C., Mota G. F., Krieger J. E., Vallada H. (2000). Angiotensinogen and angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphisms and the risk of bipolar affective disorder in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 293, 103–106 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01512-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. A., Jacobowitz D. M., Aguilera G., Catt K. J. (1991). Differential distribution of AT1 and AT2 angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the rat brain during development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 11440–11444 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein R. A., Holmes A. (2007). Effects of repeated maternal separation on anxiety- and depression-related phenotypes in different mouse strains. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31, 3–17 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithipatikom K., Holmes B. B., Isbell M. A., Hanke C. J., Gomez-Sanchez C. E., Campbell W. B. (2005). Measurement of steroid synthesis in zona glomerulosa cells by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry: inhibition by nitric oxide. Anal. Biochem. 337, 203–210 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuyt A. M., Lenkei Z., Corvol P., Palkovits M., Llorens-Cortes C. (2001). Ontogeny of angiotensin II type 1 receptor mRNAs in fetal and neonatal rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 440, 192–203 10.1002/cne.1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ognibene E., Adriani W., Caprioli A., Ghirardi O., Ali S. F., Aloe L., Laviola G. (2008). The effect of early maternal separation on brain derived neurotrophic factor and monoamine levels in adult heterozygous reeler mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 32, 1269–1276 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oitzl M. S., Workel J. O., Fluttert M., Frosch F., De Kloet E. R. (2000). Maternal deprivation affects behaviour from youth to senescence: amplification of individual differences in spatial learning and memory in senescent Brown Norway rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 3771–3780 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M., Annerbrink K., Westberg L., Melke J., Baghaei F., Rosmond R., Holm G., Andersch S., Allgulander C., Eriksson E. (2004). Angiotensin-related genes in patients with panic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 127B, 81–84 10.1002/ajmg.b.20164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel J., Benicky J., Murakami Y., Sanchez-Lemus E., Saavedra J. M. (2008). Peripherally administered angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists are anti-stress compounds in vivo. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1148, 360–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. I., de Oliveira E. M. (2008). Brain renin angiotensin in disease. J. Mol. Med. 86, 715–722 10.1007/s00109-008-0331-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. I., Sumners C. (1998). Angiotensin II in central nervous system physiology. Regul. Pept. 78, 1–11 10.1016/S0167-0115(98)00122-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky P. M., Sutton S. W., Bruhn T. O., Ferguson A. V. (1988). Analysis of the role of angiotensin II in mediation of adrenocorticotropin secretion. Endocrinology 122, 538–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky P. M., Thrivikraman K. V., Nemeroff C. B., Caldji C., Sharma S., Meaney M. J. (2005). Long-term consequences of neonatal rearing on central corticotropin-releasing factor systems in adult male rat offspring. Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 2192–2204 10.1038/sj.npp.1300769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raasch W., Wittmershaus C., Dendorfer A., Voges I., Pahlke F., Dodt C., Dominiak P., Johren O. (2006). Angiotensin II inhibition reduces stress sensitivity of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Endocrinology 147, 3539–3546 10.1210/en.2006-0198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C., Sandman C. A., Lenjavi M. R., Baram T. Z. (2008). A novel mouse model for acute and long-lasting consequences of early life stress. Endocrinology 149, 4892–4900 10.1210/en.2008-0633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld P., Suchecki D., Levine S. (1992). Multifactorial regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during development. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 16, 553–568 10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80196-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rots N. Y., de Jong J., Workel J. O., Levine S., Cools A. R., De Kloet E. R. (1996). Neonatal maternally deprived rats have as adults elevated basal pituitary-adrenal activity and enhanced susceptibility to apomorphine. J. Neuroendocrinol. 8, 501–506 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.04843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab Y. B., Gard P. R., Yeoman M. S., Mfarrej B., El-Moalem H., Ingram M. J. (2007). Renin-angiotensin-system gene polymorphisms and depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 31, 1113–1118 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra J. M., Ando H., Armando I., Baiardi G., Bregonzio C., Jezova M., Zhou J. (2004). Brain angiotensin II, an important stress hormone: regulatory sites and therapeutic opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1018, 76–84 10.1196/annals.1296.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra J. M., Benicky J. (2007). Brain and peripheral angiotensin II play a major role in stress. Stress 10, 185–193 10.1080/10253890701350735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro S., Geller E., Eiduson S. (1962). Neonatal adrenal cortical response to stress and vasopressin. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 109, 937–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M., Oitzl M. S., Levine S., De Kloet E. R. (2002a). The HPA system during the postnatal development of CD1 mice and the effects of maternal deprivation. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 139, 39–49 10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00519-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Oitzl M. S., Levine S., De Kloet E. R. (2002b). The HPA system during the postnatal development of CD1 mice and the effects of maternal deprivation. Dev. Brain Res. 139, 39–49 10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00519-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Enthoven L., van der Mark M., Levine S., De Kloet E. R., Oitzl M. S. (2003a). The postnatal development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the mouse. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 21, 125–132 10.1016/S0736-5748(03)00030-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Oitzl M. S., Müller M. B., Ohl F., Wurst W., Holsboer F., Levine S., De Kloet E. R. (2003b). Regulation of the developing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1-deficient mice. Neuroscience 119, 589–595 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00097-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Deussing J. M., Oitzl M. S., Ohl F., Levine S., Wurst W., Holsboer F., Müller M. B., De Kloet E. R. (2006a). Differential disinhibition of the neonatal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in brain-specific CRH receptor 1-knockout mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 2291–2298 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Levine S., Alam S., Harbich D., Sterlemann V., Ganea K., De Kloet E. R., Holsboer F., Müller M. B. (2006b). Metabolic signals modulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation during maternal separation of the neonatal mouse. J. Neuroendocrinol. 18, 865–874 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01482.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Enthoven L., Van Woezik J. H., Levine S., De Kloet E. R., Oitzl M. S. (2004). The dynamics of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during maternal deprivation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 16, 52–57 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Levine S., Oitzl M. S., van der Mark M., Müller M. B., Holsboer F., De Kloet E. R. (2005). Glucocorticoid receptor blockade disinhibits pituitary-adrenal activity during the stress hyporesponsive period of the mouse. Endocrinology 146, 1458–1464 10.1210/en.2004-1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. V., Sterlemann V., Wagner K., Niederleitner B., Ganea K., Liebl C, Deussing J. M., Berger S., Schütz G., Holsboer F., Müller M. B. (2009). Postnatal glucocorticoid excess due to pituitary glucocorticoid receptor deficiency: differential short- and long-term consequences. Endocrinology, doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1211. 10.1210/en.2008-1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld N. M., Leathem J. H., Rabii J. (1980). Maturation of adrenal stress responsiveness in the rat. Neuroendocrinology 31, 101–105 10.1159/000123058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam S., Llorens-Cortes C., Clauser E., Corvol P., Gasc J. M. (1995). Expression of angiotensin II AT2 receptor mRNA during development of rat kidney and adrenal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 268, F922–F930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragy H. M., Carey R. M. (2000). Prospective trials of angiotensin receptor blockers: beyond blood pressure control. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2, 163–164 10.1007/s11906-000-0076-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki D., Duarte P. B., Tufik S. (2000). Pituitary-adrenal axis and behavioural responses of maternally deprived juvenile rats to the open field. Behav. Brain Res. 111, 99–106 10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00148-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki D., Rosenfeld P., Levine S. (1993). Maternal regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the infant rat: the roles of feeding and stroking. Dev. Brain Res. 75, 185–192 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumitomo T., Suda T., Nakano Y., Tozawa F., Yamada M., Demura H. (1991). Angiotensin II increases the corticotropin-releasing factor messenger ribonucleic acid level in the rat hypothalamus. Endocrinology 128, 2248–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutanto W., Rosenfeld P., De Kloet E. R., Levine S. (1996). Long-term effects of neonatal maternal deprivation and ACTH on hippocampal mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 92, 156–163 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00213-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oers H. J., De Kloet E. R., Whelan T., Levine S. (1998). Maternal deprivation effect on the infant’s neural stress markers is reversed by tactile stimulation and feeding but not by suppressing corticosterone. J. Neurosci. 18, 10171–10179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema A. H., Reber S. O., Selch S., Obermeier F., Neumann I. D. (2008). Early life stress enhances the vulnerability to chronic psychosocial stress and experimental colitis in adult mice. Endocrinology 149, 2727–2736 10.1210/en.2007-1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bohlen und Halbach O., Albrecht D. (2006). The CNS renin-angiotensin system. Cell Tissue Res. 326, 599–616 10.1007/s00441-006-0190-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. D., Dallman M. F. (1993). Neonatal facilitation of stress-induced adrenocorticotropin secretion by prior stress: evidence for increased central drive to the pituitary. Endocrinology 132, 1101–1107 10.1210/en.132.3.1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. D., Scribner K. A., Cascio C. S., Dallman M. F. (1991). The pituitary-adrenocortical system of neonatal rats is responsive to stress throughout development in a time-dependent and stressor-specific fashion. Endocrinology 128, 1385–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver I. C. G., Cervoni N., Champagne F. A., D’Alessio A. C., Sharma S., Seckl J. R., Dymov S., Szyf M., Meaney M. J. (2004). Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 847–854 10.1038/nn1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workel J. O., Oitzl M. S., Fluttert M., Lesscher H., Karssen A., De Kloet E. R. (2001). Differential and age-dependent effects of maternal deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of brown Norway rats from youth to senescence. J. Neuroendocrinol. 13, 569–580 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00668.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. H., Dudoit S., Luu P., Lin D. M., Peng V., Ngai J., Speed T. P. (2002). Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, e15. 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]