Abstract

Objectives To assess timeliness of carotid endarterectomy services in the United Kingdom.

Design Observational study with follow-up to March 2008.

Setting UK hospitals performing carotid endarterectomy.

Participants UK surgeons undertaking carotid endarterectomy from December 2005 to December 2007.

Main outcome measures Provision and speed of delivery of appropriate assessments of patients; carotid endarterectomy and operative mortality; 30 day postoperative mortality.

Results 240 (61% of those eligible) consultant surgeons took part from 102 (76%) hospitals and trusts. Of 9913 carotid endarterectomies recorded on hospital episode statistics, 5513 (56%) were included. Of the patients who underwent endarterectomy, 83% had a history of transient ischaemic attack or stroke. Of these recently symptomatic patients, 20% had their operation within two weeks of onset of symptoms and 30% waited more than 12 weeks. Operative mortality was 0.5% during the inpatient stay and 1.0% (95% confidence interval 0.7% to 1.3%) by 30 days.

Conclusion Only 20% of symptomatic patients had surgery within the two week target time set by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Although operative mortality rates are comparable with those in other countries, some patients might experience disabling or fatal stroke while waiting for surgery and hence not be included in operative statistics. Major improvements in services are necessary to enable early surgery in appropriate patients in order to prevent strokes.

Introduction

Every year in the United Kingdom, about 120 000 people have a stroke and 20-30% die within a month. Stroke is also the single largest cause of severe disability in adults, with nearly a million people living with the after effects of stroke, a third of whom have long term disability. Stroke costs the economy £7bn (€8bn, $11bn) a year: £2.8bn in direct hospital care, £2.4bn in costs of informal care, and £1.8bn in lost productivity.1 Outcomes in the UK have been poor compared with other Western, particularly European, countries.2

Pooled analysis of data from individual patients from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy versus medical treatment alone for symptomatic carotid stenosis showed that surgery reduced the risk of stroke in patients with 50-99% carotid stenosis3 but that the benefit decreased substantially if surgery was delayed for more than two weeks after the presenting event.4 In 2004, however, the RCP Sentinel Audit reported that only half of stroke patients had carotid imaging within 12 weeks.5 Delays between imaging and subsequent surgery were not recorded. An Oxfordshire study found median time from transient ischaemic attack or stroke to imaging was over four weeks and median delay to surgery was 14 weeks.6 Randomised patients from the UK in a recent trial of local versus general anaesthetic had a 12 week delay to surgery,7 and similar delays were reported in an audit of all symptomatic endarterectomy patients in Scotland in 1997-9 and again in 2005-7.8 9 The 2006 RCP Sentinel Audit showed some improvement in speed of diagnosis, investigation, and treatment of transient ischaemic attack and stroke,10 but delays in investigation and treatment were still excessive. Although delays to surgery have been reduced substantially in some centres,11 there are no published data on current performance nationally.

In the UK, around 4500 carotid endarterectomies are performed each year, but it is not known how many patients have had preceding symptoms and how long they have had to wait for operation. Each operation costs just over £300012 (€3380, $4500), but no cost effectiveness analysis has been done to determine whether the procedures, as performed in the UK, effectively prevent future strokes. Many more carotid endarterectomies are done in other countries; Canada does eight times, Australia 10 times, and the United States up to 30 times as many carotid endarterectomies per 100 000 population,1 although many of these procedures are for asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

The purpose of the UK Carotid Endarterectomy study was to assess the quality of carotid endarterectomy services and the mortality within 30 days of operation. The study was organised in two parts. Part 1 comprised two surveys in December 2005 and December 2006 describing the organisation of care within the UK. Part 2 was a clinical study of patients undergoing surgery between 1 December 2005 and 31 December 2007, with follow-up completed by 31 March 2008, the results of which are presented here.

Methods

We contacted every acute hospital in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland to ascertain the number of surgeons who performed carotid endarterectomy and wrote to each individually and invited them to participate. We also obtained data for each trust (each hospital in Scotland) from the hospital episode statistics or equivalent body for each country to use for comparison.

Surgeons were asked to submit all data on all carotid endarterectomies they performed over the study period (December 2005 to December 2007) via a web based tool whose definitions (help text) were accessible online. All required data items were collectable within the hospitals’ routine systems, and anonymous codes were used to protect the identities of patients, surgeons, and hospitals. Professionals submitting the data included surgeons, nurse specialists, specialist registrars, and clinical fellows. Overall responsibility for the data quality lay with the surgeon who performed the operation. In cases where the patient was assessed by the surgeon who performed the operation, we sought no external validation. The web tool contained mandatory fields and online data logic/consistency checks, which ensured the “minimum dataset” was fully completed and good data quality submitted.

For each operation, we collected data in two phases: preoperative and operative data up to discharge (phase 1) and data on 30 day survival and follow-up outcome assessment (phase 2) (box).

Clinical data

Phase 1 (preoperative and operative data up to discharge)

Demographics (date, hospital code, patient’s date of birth, sex, ethnicity)

Admission (date, mode of entry, such as elective)

History (diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, smoking, hypertension)

Referral (source, date)

Indications (symptoms, when they occurred)

Imaging at time of referral (date, type, stenosis, brain imaging)

Confirmatory carotid imaging before operation (date, type, stenosis)

Most recent symptom and neurological status before surgery (time, Rankin score)

Previous carotid intervention (surgery, angioplasty)

Preoperative tests (electrocardiography, blood pressure, blood tests)

Preoperative drug use (aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, warfarin, statins, β blockers)

Operation (date, side, grade of surgeon, type of anaesthetic, anaesthetist grade)

Procedure (time taken, use of shunt, patch, tacking sutures)

Level of postoperative care (such as high dependency unit)

Complications and timing (myocardial infarct, stroke, death, other, such as cranial nerve damage)

Discharge (date, destination, Rankin score)

Phase 2 (30 day survival and follow-up outcome assessment)

Patient status at 30 days (dead, date, cause)

Follow-up visit (offered, attended, date, seen by whom)

Complications (reoperation, date, cranial nerve injury, stroke (including date), Rankin score)

Drug use (aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, warfarin, statin, β blocker)

Once phase 1 was completed and actively submitted for analysis, the relevant sections were “locked.” Phase 2 questions were accessible only once phase 1 was successfully completed. To cater for variations between the patients’ review times, we allowed a period of three months. The minimum criterion for inclusion of a case in the analyses was completion of phase 1.

Results

We identified 396 eligible surgeons, and 240 (61%) contributed cases to the study. The median number of cases per surgeon was 18 (interquartile range 8-32). In this study we have included only those patients who underwent surgery. We do not know how many operations were cancelled because the carotid stenosis had progressed to occlusion before surgery or how many patients had a disabling or fatal stroke before they could undergo surgery.

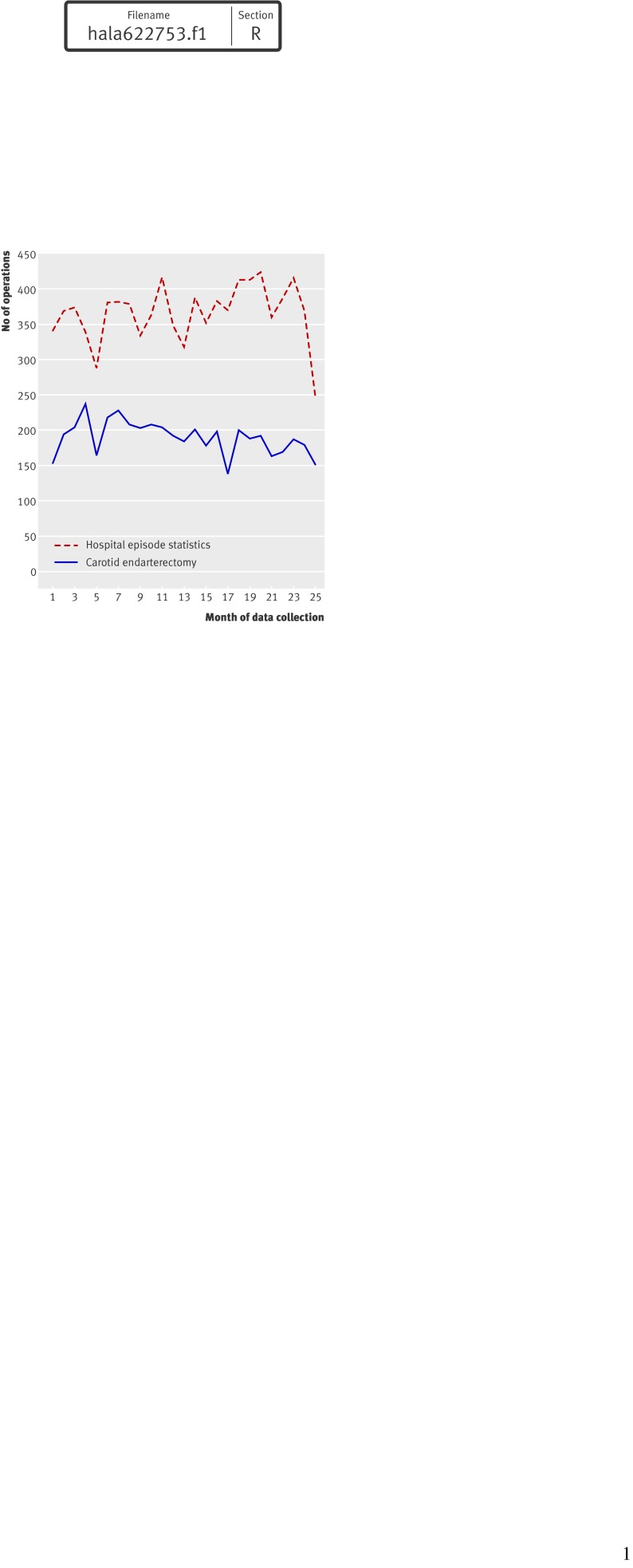

Phase 1 details were complete for 5513 patients (including 16 from the private sector) by 31 March 2008 (from 240 surgeons in 120 hospitals). Baseline phase 2 data were available for 4964 cases (from 206 surgeons in 105 hospitals), and complete data were available for the 4404 patients who attended follow-up appointments. The total number of cases listed on hospital episode statistics as “carotid endarterectomy with or without patching” for the data collection period of this study was 9913, giving a 56% rate of case submission (table 1). In England, monthly case ascertainment compared with hospital episode statistics data (figure) remained constant across the data collection period.

Table 1 .

Regional contributions to survey by country and hospital/trust

| Region | HES (based on contributing hospitals only) | Eligible hospitals/trusts | Eligible surgeons | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | No (%) of cases contributed for this round by 31 March 08 | No of hospitals | No (%) contributing at least one case by 31 March 2008 | No of surgeons | No (%) contributing at least one case by 31 March 2008 | |||

| England | 7056 | 4718 (67) | 114 | 88 (77) | 341 | 211 (62) | ||

| N Ireland | 324 | 162 (50) | 3 | 3 (100) | 10 | 8 (80) | ||

| Scotland | 793 | 376 (47) | 9 | 7 (78) | 26 | 12 (46) | ||

| Wales | 530 | 234 (44) | 9 | 4 (44) | 19 | 9 (47) | ||

| UK/total | 8703 | 5497 (63) | 135 | 102 (76) | 396 | 240 (61) | ||

HES=hospital episodes statistics.

Month by month hospital episode statistics for England

Of the 5513 patients, 3751 (68%) were men, with mean age of 70 (71 for women). Twelve per cent of all patients were aged over 80 (660/5513), 2.9% over 85 (160/5513), and 0.6% over 90 (31/5513). Most patients were British white (95%, 5115/5377), the next largest group being British Asian (1.1%, 58/5513), which is consistent with the known predominance of carotid disease in the white population. Twenty one per cent (1178/5509) had diabetes, and 32% (1762/5513) had a history of ischaemic heart disease or chronic heart failure. Thirty one per cent (1671/5476) were current smokers. The commonest risk factor for stroke, hypertension, was present in 80% of patients (4403/5492), with 1.4% (79/5492) untreated on admission.

Sixteen per cent of cases (889/5513) were recorded as being asymptomatic, with the 84% remaining having some symptom attributable to carotid disease. Of these, 41% (1914/4624) had a transient ischaemic attack, 35% (1634/4624) had stroke, 20% (916/4624) had amaurosis fugax, and 3% (160/4624) none of these three symptoms. Previous ipsilateral carotid surgery was recorded for 1.8% (99/5513) of patients and angioplasty for 0.4% (20/5513).

The referral source was recorded for all cases. Stroke (38%, 2117/5513) or care of the elderly (13%, 717/5513) physicians referred most patients, with neurologists (11%, 596/5513) and general practitioners (13%, 701/5513) referring substantial numbers. The 1382 other referrals came from sources including cardiologists, ophthalmologists, and other vascular surgeons. The fastest pathway from referral to surgery was through neurologists (median delay 25 days, interquartile range 10-63 days) and stroke physicians (30, 16-67 days). Referrals through care of the elderly physicians (48, 24-85 days) and general practitioners (68, 34-151 days) were considerably slower.

There was considerable delay between the most recent symptom and surgery (table 2). Nearly a third (1372/4591) of patients waited more than 12 weeks, and only 20% (944/4591) underwent surgery within two weeks.

Table 2.

Delay between most recent symptom and surgery

| Delay (weeks) | No of cases* (%) |

|---|---|

| ≤2 | 944 (20) |

| 2-4 | 654 (14) |

| >4-12 | 1621 (34) |

| >12 | 1372 (30) |

*Total=4591; 33 missing.

Delays from referral to operation were considerable. The median delay from referral to surgery was 40 days (17-84 days). During the survey there was a trend towards reduction in this delay from 43 (19-88) to 38 (16-81) to 34 (13-79) days (dividing the data collection into three equal time periods). Once admitted, 15% (818/5513) had their operation on the day of admission, and 94% (5186/5513) were operated on within two days.

Preoperatively, 90% of patients were taking a statin (4982/5513) and 32% (1781/5512) were taking a β blocker. Nearly all (5378/5513) were taking at least one antithrombotic drug before surgery (table 3). Antiplatelet therapy was stopped before surgery in 11% (514/4627) of those taking aspirin and 51% (468/922) taking clopidogrel (usually in addition to aspirin). Five per cent (289/5363, 15 missing data) were taking warfarin, which was almost always stopped (273/284, 96%) before surgery (table 3).

Table 3.

Proportion of antithrombotic drug use before and after endarterectomy

| Drug (s) | Preoperative (n=5513) | Postoperative (n=4471) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 60.5 | 49.9 |

| Clopidogrel | 7.0 | 6.2 |

| Dipyridamole | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Aspirin + dipyridamole | 18.7 | 24.7 |

| Aspirin + clopidogrel | 7.3 | 9.8 |

| Clopidogrel + dipyridamole | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Warfarin | 4.8 | 5.0 |

| Any combination of antiplatelet drugs | 95.1 | 94.2 |

| Any antiplatelet + warfarin | 99.9 | 99.2 |

Surgery on the left carotid artery was slightly more common (52%, 2863/5504; data missing for nine) than on the right. Some 3733 patients underwent confirmatory imaging (a second ultrasound examination after the initial duplex scan to confirm that the carotid artery was still patent before surgery) of the ipsilateral carotid before operation, and the level of stenosis was available for all but 16 cases. Seven per cent (269/3717) of patients had 50-69% stenosis, 55% (2032/3717) had 70-89% stenosis, and 35% (1285/3717) had 90-99%. One per cent (28/3717) had less than 50% stenosis, and 3% (103/3717) were ungraded. The level of stenosis in the contralateral carotid artery was missing for 25 cases and not imaged in 1075 cases. Fifty six per cent of cases (1462/2633) had less than 50% contralateral stenosis, 14% (381/2633) had a level of 50-69%, 19% (498/2633) had 70-99%, and 11% (292/2633) had an occluded artery. The methods used to assess duplex stenosis were not specified, but, in the organisational surveys, hospitals were found to have used different methods (NASCET (North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial), ECST (European carotid surgery trial), and common carotid artery (CCA)), which could result in variation in stenosis; however, this was not the only assessment of the stenosis, and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and computed tomography angiography (CTA) were often carried out, contributing to the decision to undertake surgery.

Phase 2 (follow-up) data were known for 4964 (90%) patients. Ninety five per cent (4593/4818) were offered an appointment, and, of these, 96% (4404/4593) attended, with median time from operation to follow-up of 50 days (41-65 days). Rankin scores at follow-up were known for 4389 patients and were broadly similar to the scores at discharge (data not shown; they are less reliable because they measure a broad range of disability, which is not necessarily related to stroke).

Most patients (91%, 4499/4964) were taking antithrombotic drugs, the type being specified for 4471: aspirin in 85%, clopidogrel or dipyridamole, or both, in 35%, and warfarin in 5%, despite about 17% of patients having atrial fibrillation (table 3). Eighty four per cent (4158/4964) were taking statins, and 21% (1054/4934) were taking β blockers.

Inpatient mortality was 0.5% (29/5512). The principal cause of inpatient death was stroke, followed by myocardial infarction. Risk of inpatient death increased with age (0.1% (1/820) at <60 years, 0.6% (23/4032) at 60-80 years, 0.8% (5/660) at >80 years. The 30 day mortality was 1.0% (48/4944); 30 day survival was not known for seven patients. Of the 5512 patients, 101 (1.8%) were reported to have had a stroke as an inpatient and of these 67 had the stroke within 24 hours of surgery, which gives a 24 hour stroke rate of 1.2%. Thirty patients had a stroke after discharge, three of whom had already had a stroke during their inpatient stay. The rate of stroke from admission to follow-up was 2.6% (124/4681) (table 4).

Table 4 .

Reported outcomes and complications. Figures are percentages (numbers) of patients

| Outcome/complication | Inpatient | Inpatient/within 30 days of surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 0.5% (29/5512) | 1.0% (48/4944) |

| Stroke | 1.8% (101/5512)* | 2.6% (124/4681)† |

| Death/stroke | 2.1% (118/5512) | 2.5% (124/4918) |

*“Perioperative” as classified by surgeons retrospectively.

†Strokes after discharge could be reported at any point. Date recorded in 24/30; 18 occurred within 30 days of operation, but as date missing for six, total within 30 days could be as high as 24.

Discussion

This large survey of carotid endarterectomy practice in the UK shows that the operation is underused compared with other similar countries. Surgeons abroad might be driven by “fee for service” and certainly perform many more operations for asymptomatic disease. It is possible, however, that of the 120 000 people who have a transient ischaemic attack or stroke every year in the UK at least 10 000 might be suitable candidates for carotid endarterectomy yet only 4500 procedures are being performed each year. There are no data indicating the specific suitability of stroke patients for surgery, but current use in Scotland is estimated at 4-5%.9

Comparison with other studies

Studies of performance of endarterectomy in the UK have been published over the past 10 years,6 7 8 13 but an up to date survey was required for several reasons. It has only recently been fully appreciated that the risk of major stroke is high during the first few days and weeks after a transient ischaemic attack or non-disabling ischaemic stroke.14 15 Delays to carotid endarterectomy are therefore associated with a high risk of stroke before surgery,6 and the benefit of surgery consequently falls rapidly with increasing delay.4 There have also been major changes in clinical practice in recent years, including changes in the way that patients being considered for carotid endarterectomy are investigated, changes in operative and anaesthetic procedures, and the increasing use of carotid stenting instead of surgery.16

Recently published NICE guidelines suggest that carotid endarterectomy should be performed in appropriate patients within two weeks of presenting symptoms. The most important finding of our survey is the unacceptable delays between symptom and operation in the UK. Indeed, if our results are compared with previous studies, there is little evidence of improvement since those data were published supporting the need for earlier surgery.

Two prospective population based studies identified all patients undergoing carotid imaging for transient ischaemic attack or stroke in Oxfordshire (population studied 680 772) in 2002-3 and in the Oxford Vascular Study (OXVASC) subpopulation (population 92 000) in 2002-4.6 Among 853 patients who had carotid imaging in the Oxfordshire population, median (interquartile range) times from presenting event to referral, scanning, and endarterectomy were 9 (3-30), 33 (12-62), and 100 (59-137) days, respectively. Forty nine patients had endarterectomy, but only three (6%) had surgery within two weeks of their presenting event and only 21 (43%) within 12 weeks. Risk of stroke before endarterectomy in those with 50-99% stenosis was 32% (17-47%) at 12 weeks, and half the strokes were disabling or fatal.

In the recent GALA trial (multicentre randomised trial of general versus local anaesthesia for carotid endarterectomy) the first 1001 UK patients randomised had a median delay between symptoms and surgery of 82 days.7

There were differences in speed of referral from different physicians in our survey. Neurologists and stroke physicians might have speedier access to imaging facilities than other specialties and some have dedicated joint transient ischaemic attack and stroke clinics shared with vascular surgeons as well as regular multidisciplinary team meetings. Other specialties are less “stroke” orientated, and this might explain their slower service, but implementation of new stroke policies should help to reduce delays, especially if common pathways are streamlined within new services.

A prospective independent survey of all carotid endarterectomies was performed in Scottish National Health Service hospitals over two 13 month periods from September 1997 and February 1999.8 Thirteen hospitals performed 485 carotid endarterectomies in the first period and 392 in the second, equating to an overall annual rate of 79 per million population. During both periods at least 95% of operations were done for symptomatic carotid stenosis. About 40% of patients were seen by a surgeon within two weeks of referral, of whom only about 40% were operated on within one month thereafter. More recent updates of carotid endarterectomy in Scotland took place in 2005 and 2007; these took into consideration the published SIGN guidelines (not including 2008) and NHSQIS (National Health Service Quality Improvement Scotland) clinical standards and reported on the 482 interventions (448 carotid surgery) performed in 2005. The mean time from referral to seeing the surgeon was 10.8 days, with a mean time from surgical consultation to surgery of just over three weeks (22.5 days). Overall, only 38% had their intervention within the Scottish target of 30 days.9 This is similar to our findings of 34% being operated on within four weeks of their symptoms (table 2).

Implementing faster surgical referral

The Department of Health’s stroke strategy now recommends that carotid surgery should be carried out within 48 hours of symptoms, when the risk of stroke is highest, in patients with transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke who are neurologically stable.17 To achieve this, the use of FAST (Face Arm Speech Test) might help the public to recognise transient ischaemic attack and early stroke,17 and the ABCD2 score18 will help primary and secondary care services to identify those patients with transient ischaemic attack who are at highest risk of stroke. Imaging services will need to provide carotid ultrasonography seven days a week, and carotid surgery in symptomatic patients will need to be regarded as an urgent procedure, having precedence over elective cases. A weekly multidisciplinary team meeting to assess suitability for surgery will be insufficient because operations will need to be scheduled for the next day. Anaesthetic staff with a special interest in vascular anaesthesia will also need to be available at short notice.

Operative mortality in our study was about 1% and is comparable with large randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis,3 4 and with systematic reviews of published surgical case series.19 20 In the Scottish Audit from 2007, the 30 day mortality was 3% (95% confidence interval 1% to 5%) and the risk of stroke within 30 days of intervention was 5% (2% to 6%).9 Some deaths and strokes occur after discharge, and, in our survey, half the deaths occurred outside hospital. Strokes are under-reported when surgeons report their own operative outcomes, and the risk of death and non-fatal stroke in our survey (2.5%) is much lower than that in symptomatic trials with independent assessment of patients by neurologists or stroke physicians. Most patients (75%) in the 2007 Scottish Stroke Care Audit were followed up in a neurovascular clinic, and in the future stroke physicians and neurologists (especially outside Scotland) should improve their service by providing independent assessment before discharge and at final outpatient follow-up.9 21 22

Earlier operation in symptomatic patients will have lasting benefit on stroke prevention.4 23 24 If possible more symptomatic patients should be fast tracked, allowing them to benefit from early surgery. Further research is required to identify the appropriate proportion of younger (up to 75 years) patients with asymptomatic stenosis in whom prophylactic surgery will provide cost effective stroke-free survival.25 26

Limitations of study

As with all studies of this nature, it is important to acknowledge the limitations. The data were self reported by the proportion (61%) of UK surgeons who took part and a considerable number of surgeons did not contribute for various reasons. A comparison with the Scottish data for the same period suggests that the delays are similar but that stroke rates might be under-reported.9 Some of the contributing surgeons might not have submitted all their cases, if hospital episode statisics are correct, again calling into question the apparently low operative risk of stroke. Not all the patients in the survey attended a follow-up appointment and this might be another reason for the low reported rates of complications. In addition, the survey captured only those patients undergoing surgery and there might have been other patients potentially eligible for carotid endarterectomy who did not receive surgery. Nevertheless, the process data are likely to be reasonably reliable and have important implications for routine clinical practice, particularly in relation to delays in investigation and treatment.

What is known about this topic

Stroke and transient ischaemic attack are common causes of death and disability in the UK

Many patients do not report symptoms of transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke promptly and there is a high risk of stroke within 30 days

A considerable proportion of symptomatic patients have tight carotid stenosis

Early carotid endarterectomy after symptoms will effectively prevent future stroke

What this paper adds

Most UK patients have carotid surgery after symptoms, but there are long delays between symptoms and surgery

Only a fifth of symptomatic patients have surgery within the two weeks recommended by NICE guidelines

Carotid endarterectomy for symptoms is urgent and should have priority over elective surgery

The large number of cases collected is a tribute to the hard work and dedication of the surgeons and their teams in submitting data. We thank Professor Walter Holland who encouraged us and the Stroke Association and the Chest, Heart and Stroke Association of Northern Ireland who sponsored the pilot study.

Contributors: AWH and DK carried out the pilot study. All authors as members of the Carotid Endarterectomy Steering Group were responsible for the design and execution of the study, DK was responsible for data collection and RG for data analysis. AWH is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the Healthcare Commission (now Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership), and the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) contributed to the funding of the web-based data collection tool. The authors are independent of the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b1847

References

- 1.National Audit Office. Reducing brain damage: faster access to better stroke care. London: NAO, 2005.

- 2.Leal J, Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray A, Peterson S, Rayner M. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the enlarged European Union. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Taylor W, Mayberg MR, et al. Pooled analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 2003;361:107-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HM. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet 2004;363:915-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Physicians/Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guidelines for stroke. 2nd ed. London: RCP, 2004.

- 6.Fairhead JF, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Population-based study of delays in carotid imaging and surgery and the risk of recurrent stroke. Neurology 2005;65:371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellagrammaticas D, Lewis S, Colam B, Rothwell PM, Warlow CP, Gough MJ, GALA trial collaborators. Carotid endarterectomy in the UK: acceptable risks but unacceptable delays. Clin Med 2007;7:589-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pell JP, Slack R, Dennis M, Welch G. Improvements in carotid endarterectomy in Scotland: results of a national prospective survey. Scott Med J 2004;49:53-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroke Services in Scottish Hospitals. www.strokeaudit.scot.nhs.uk/downloads.htm.

- 10.Royal College of Physicians/Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guidelines for stroke. 2nd ed. London: RCP, 2006.

- 11.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, Geraghty O, Redgrave JN, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2007;370:1432-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health. Payment by results tariff. 2009. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Financeandplanning/NHSFinancialReforms/DH_900.

- 13.McCollum PT, da Silva A, Ridler BD, DeCossart L. Carotid endarterectomy in the UK and Ireland: audit of 30-day outcome. Audit Committee for the Vascular Surgical Society. Eur Jour Vasc Endovasc Surg 1997;14:386-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA 2000;284:2901-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM, on behalf of the Oxford Vascular Study. Early risk of stroke after a TIA or minor stroke in a population-based incidence study. BMJ 2004;328:326-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ederle J, Featherstone RL, Brown MM. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting for carotid artery stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health. National stroke strategy 2007. www.dh.gov.uk/publications.

- 18.Nor AM, McAllister C, Louw SJ, Dyker AG, Davis M, Jenkinson D, et al. Stroke agreement between ambulance paramedic- and physician-recorded neurological signs with face arm speech test (fast) in acute stroke patients. Stroke 2004;35:1355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Giles MF, Elkins JS, Bernstein AL, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2007;369:283-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bond R, Rerkasem K, Rothwell PM. A systematic review of the risks of carotid endarterectomy in relation to the clinical indication and the timing of surgery. Stroke 2003;34:2290-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothwell PM, Slattery J, Warlow CP. A systematic review of the risks of stroke and death due to carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic stenosis. Stroke 1996;27:260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Is self-audit reliable? Lancet 1995;346:1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, Eliasziw M, Warlow CP, Barnett HJM. Sex difference in effect of time from symptoms to surgery on benefit from endarterectomy for transient ischaemic attack and non-disabling stroke. Stroke 2004;35:2855-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairhead JF, Rothwell PM. The need for urgency in identification and treatment of symptomatic carotid stenosis is already established. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005;19:355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 1995;273:1421-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative group. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1491-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]