Abstract

AIM: To analyze the prognostic factors involved in survival and cancer recurrence in patients undergoing surgical treatment for colorectal liver metastases (CLM) and to describe the effects of time-related changes on survival and recurrence in these patients.

METHODS: From January 1994 to January 2006, 236 patients with CLM underwent surgery with the aim of performing curative resection of neoplastic disease at our institution and 189 (80%) of these patients underwent resection of CLM with curative intention. Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data, including primary tumor and CLM pathology results, were retrospectively reviewed. Patients were divided into two time periods: a first period from January 1994 to January 2000 (n = 93), and a second period from February 2000 to January 2006 (n = 143).

RESULTS: Global survival at 1, 3 and 5 years in patients undergoing hepatic resection was 91%, 54% and 47%, respectively. Patients with preoperative extrahepatic disease, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels over 20 ng/dL, more than four nodules or extrahepatic invasion at pathological analysis had worse survival. Tumor recurrence rate at 1 year was 48.3%, being more frequent in patients with preoperative and pathological extrahepatic disease and CEA levels over 20 ng/dL. Although patients in the second time period had more adverse prognostic factors, no differences in overall survival and recurrence were observed between the two periods.

CONCLUSION: Despite advances in surgical technique and better adjuvant treatments and preoperative imaging, careful patient staging and selection is crucial to continue offering a chance of cure to patients with CLM.

Keywords: Liver metastases, Colorectal cancer, Hepatic resection, Survival, Prognostic factors

INTRODUCTION

Up to 50% of patients with colorectal carcinoma (CRC) will develop metastases during the course of their disease, leading to certain death if untreated[1,2]. Colorectal liver metastases (CLM) are present in 15% to 25% of cases at the time of diagnosis of primary tumor, and another 25% to 50% will develop metachronic CLM within 3 years following resection of primary CRC[1,3–6].

Surgical resection remains at the present time the only potentially curative treatment for patients with CLM, even though hepatic resection is only possible in less than 25% of patients with metastatic disease limited to the liver[1,5,6]. Although neoplastic recurrence is observed in up to 50% of patients and remains a basic determinant of survival, only 20%-30% of these patients are potentially amenable to repeat hepatic resection[7,8]. Five-year survival after curative resection ranges 30%-40%, whereas less than 2% of patients are alive 5 years after diagnosis without surgical therapy[5,6,9].

Many attempts have been made to classify patients into stratification groups in order to determine which patients would obtain most benefit from resection, even though the most used classification remains the clinical risk score (CRS) described by Fong et al[9–11]. According to these scores, CLM resection should be put into question in high-risk patients because of poor expected results after surgery, and therefore these patients should be included in chemotherapeutical trials. In recent years an increase in indications for resection of CLM has been observed due to a multidisciplinary approach with improvements in surgical techniques, anesthetic management and the introduction of new chemotherapy drugs[12–15]. This approach has led to an extension of the traditional limits of CLM resectability with promising results, although the number of patients is still too small to draw definitive conclusions[16,17].

Taking all these facts into consideration, the aims of our study were to analyze the survival and recurrence of patients with CLM undergoing surgical treatment in our hospital, to determine whether any single factor was significantly associated with survival and recurrence, and to describe the effects of time-related changes in our series of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 1994 to January 2006, 236 consecutively recruited patients with CLM were operated on in our institution with the aim of performing curative resection of neoplastic disease. Among them, 189 patients (80%) underwent curative hepatic resection (defined as resection of all macroscopic neoplastic tissue found during laparotomy), with 18 patients undergoing resection of extrahepatic disease at the same time.

CLM resection criteria at the hospital clinic

Criteria for resection of CLM have changed over time and, in general, these indications were more restrictive at the beginning of the series and have expanded as surgical experience and better perioperative care of patients has been acquired. The classically accepted indications for CLM surgery in our institution are: (1) patients presenting with 4 or less nodules, (2) remaining liver parenchyma over 25% of total liver volume and (3) no extrahepatic neoplastic disease (defined as the presence of metastatic neoplastic tissue beyond the limits of hepatic capsule). However, the definitive guiding criteria used to consider or refuse a patient for CLM resection is the possibility of benefit from a complete resection of neoplastic disease with enough functional residual liver, despite the localization and number of lesions and an adequate physical status to tolerate liver resection (defined by a performance status under 3 and an absence of serious associated illnesses). All prospective surgery patients with CLM are evaluated and staged with radiological studies (chest X-ray, abdominopelvic CT or MRI scan, occasionally complemented with liver volumetry in cases when predicted liver remnant is small, as well as PET scan in cases when extrahepatic invasion is suspected), laboratory tests including liver function tests, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay and a complete colonoscopy. Candidates are presented to a CRC committee meeting composed of liver and colorectal surgeons, oncologists and radiologists.

Liver resection technique for CLM

Despite several changes in the resection technique during the time considered in the study, the main technical points for CLM resection have remained constant over time (J-shaped skin incision in the upper right quadrant, intraoperative ultrasonography (IOUS) and liver transection with an ultrasonic dissector under Pringle maneuver if needed).

Although the increasing use of laparoscopic techniques in colorectal resections has led to a reduction in the amount of surgical trauma[18], thus making one-step resection of CRC and CLM possible, the majority of our patients with synchronous CLM usually undergo colorectal and liver resection in two separate stages. In cases when simultaneous resection is planned, patients are operated on by two coordinated different teams of surgeons specialized in hepatic and colorectal surgery respectively. Colorectal resection is always performed first and the decision about performing liver resection at the same operation is taken depending on the type and extent of colorectal and liver resection, and any intraoperative findings that might recommend a two-stage procedure.

Postoperative follow-up of patients with CLM

After discharge from hospital, patients are followed by a multidisciplinary team of oncologists, colorectal and hepatic surgeons and postoperative status and pathologic results are then reviewed. Depending on the previous treatments, overall risk and tolerance, patients are proposed to be treated with complementary chemotherapy, mainly based on 5-fluorouracil and either irinotecan or oxaliplatin, although in recent times the use of cetuximab as an adjuvant agent has increased. Usual postoperative follow-up in order to detect neoplastic recurrence consists of physical examination, laboratory tests with liver function tests and CEA assay, and abdominal ultrasonography or CT every 3 mo during the first 2 years and every 6 mo after the second year.

CLM resection data

Patients were classified according to the interval between the diagnosis of CLM and CRC resection. CLM diagnosed before, during or within 90 d of CRC resection were classified as synchronous and those CLM diagnosed at least 90 d after CRC resection were classified as metachronous.

In order to study the evolution of CLM resection over time, the entire series of patients was divided into two periods of equal length: the first period from January 1994 to January 2000 and the second period from February 2000 to January 2006.

Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data including CRC and CLM pathology results were retrospectively reviewed.

Definitions of interventions and results

Combined hepatectomy was defined as any major (three or more segments) or minor (less than three segments) hepatectomy with any associated atypical (non-anatomical) resection.

Neoplastic recurrence was diagnosed by at least two coinciding image techniques or surgical exploration at least 30 d after liver resection. Survival was calculated using the last follow-up date (January 31, 2008) or the date of expiration.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using Student’s t test. When a normal distribution was not present, continuous variables were expressed as the median and the range and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Patient survival and recurrence were calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier, and the log rank test was used to compare survival in the univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis was calculated using a Cox regression model.

A P value under 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the “Statistical Package for the Social Sciences” version 11.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Demographic and preoperative data of the patients in the series are shown on Table 1. Overall median follow-up was 5.8 years, with a minimum follow-up of 1 year and maximum of 14 years. By time periods, median follow-up in the first period group was 9.3 years, while in the second period group was 3.8 years.

Table 1.

Demographic and preoperative characteristics of the patients n (%)

| Characteristics | |

| Total patients | 236 |

| Age (yr) (mean, range) | 63 (36-81) |

| Sex (male/female) | 153/83 |

| Metachronous metastases (> 3 mo) | 88 |

| Synchronous metastases | 137 |

| Previous CLM resection | 11 |

| Localization of primary tumor | |

| Rectum | 71 (30) |

| Colon | 165 (70) |

| Differentiation of primary tumor | |

| Poor differentiated | 32 (14.4) |

| Moderately differentiated | 176 (78.9) |

| Well differentiated | 15 (6.7) |

| Adjuvant treatment of primary tumor | |

| Chemotherapy | 97 (41.1) |

| Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy | 39 (16.5) |

| Radiotherapy alone | 5 (2.1) |

| No treatment | 95 (40.3) |

| Number of hepatic metastases | 2 (1-11) |

| Bilobar distribution | 76 (32.5) |

| Size of metastases (cm) | 3 (0.3-12) |

| Associated disease | 164 (72.2) |

| Anesthetic risk | |

| ASA I-II | 150 (63.6) |

| ASA III-IV | 86 (36.4) |

| Previous treatment of metastases | 62 (27.3) |

| Preoperative CEA (ng/dL) | 10.35 (0.4-3203) |

| Extrahepatic invasion | 11 (4.8) |

Primary tumor-related and preoperative factors

Synchronous metastases, colonic localization of the primary tumor and parameters related to a low risk CRS accounted for the majority of patients in the series, even though some cases had extreme size and number of CLM. Over half of the patients had received some adjuvant treatment for CRC (five patients having received radiotherapy, 97 patients having received chemotherapy and 39 patients having received both treatments). Preoperative treatment before hepatic resection was given to 62 patients, the majority of them receiving 5-fluorouracil-based systemic chemotherapy because of synchronous or initially non-resectable metastases (Table 1).

Intraoperative results

217 patients (92%) underwent IOUS. We found a higher amount or more invasive hepatic lesions than in the preoperative evaluation in 30% of the patients, leading to non-resection in half of these patients. 38 patients were found to have extrahepatic disease at the time of laparotomy, and in 18 of them a curative resection with resection of extrahepatic disease could be achieved. 159 patients (72%) underwent another procedure associated with liver resection, mainly cholecystectomy (105 patients) but also including colectomy (11 patients), splenectomy (one patient) and diaphragmatic and vascular resection (five patients) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operative characteristics of the patients n (%)

| Characteristics | |

| Intraoperative ultrasonography | 92% |

| Number of metastases (median, range) | 2 (0-15) |

| Extrahepatic invasion | 38 (16.1) |

| Type of resection | |

| Major hepatectomy | 51 (21.6) |

| Minor hepatectomy | 66 (28) |

| Atypical hepatectomy | 36 (15.3) |

| Combined hepatectomy | 36 (15.3) |

| No resection | 47 (19.9) |

| Resection of extrahepatic disease | 18 (7.5) |

| Peritoneal disease | 4 |

| Diaphragmatic invasion | 4 |

| Local disease (colon/rectum) | 4 |

| Hilar lymph node invasion | 3 |

| Inferior vena cava invasion | 2 |

| Splenectomy | 1 |

| Additional procedure | 159 (72) |

| Blood loss (mL) (median, range) | 370 (0-2500) |

| Vascular inflow exclusion | 56.8% |

| Vascular exclusion time (min) | 33 (4-128) |

| Need of transfusion | 82 (36.8) |

| Surgery time (min) | 220 (30-420) |

Postoperative results (Table 3)

Table 3.

Postoperative results of patients undergoing curative resection n (%)

| Postoperative results | |

| Number of metastases (median, range) | 2 (1-18) |

| Size of metastases (cm) (median, range) | 3.25 (0.7-15) |

| Pathological extrahepatic invasion | 22 (12.3) |

| Margins | |

| > 1 cm | 33.5% |

| < 1 cm | 42.3% |

| Invaded | 24.2% |

| Hospital stay (d) | 9 (4-43) |

| Postoperative mortality | 4 (1.7) |

| Major postoperative morbidity | 11 (4.7) |

| Postoperative treatment | 100 (52.9) |

| Neoplastic recurrence at 1 yr | 77 (40.9) |

Pathological data: Non-involved margins (defined as the absence of tumor at any edge of the resection piece at the pathological examination) were achieved in 75.8% of patients. Extrahepatic invasion on pathological analysis was found in 12.3% of patients. When comparing the number of nodules found at pathological examination with the ones preoperatively diagnosed, 28% of patients showed more nodules, whereas only 18.2% of patients had more nodules at pathological examination compared with the number diagnosed intraoperatively by IOUS.

Clinical data: Global postoperative mortality in the series was 1.7%. Minor postoperative complications were described in 41.1% of the patients in the series, with nine patients suffering biliary leak, nine patients having postoperative hepatic failure and only one case of postoperative bleeding. 4.7% of patients had major postoperative complications but only eight patients needed reoperation (4 due to intestinal fistula or perforation, 2 due to wound evisceration and one due to postoperative bleeding and infection).

Outpatient data: After resection, chemotherapeutic adjuvant treatment (based mainly on 5-fluorouracil alone or combined with irinotecan or oxaliplatin) was given to 52.9% of the patients.

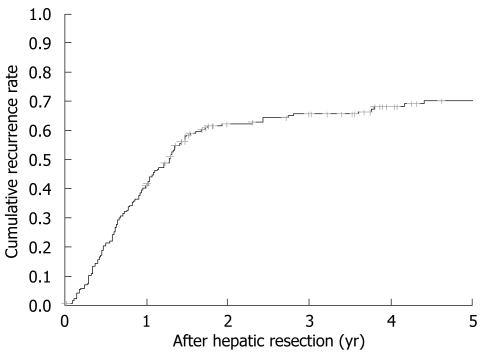

Recurrence analysis

Tumor recurrence rate at 1, 3 and 5 years was 40.9%, 66% and 70.4% with a median tumor-free survival of 1.42 (0.4-1.9) years (Figure 1). When performing unifactorial analysis, preoperative extrahepatic disease (P = 0.02), CEA levels over 20 ng/dL (P = 0.017), nodules larger than 5 cm at pathological examination (P = 0.043) and extrahepatic disease at pathological examination (P = 0.009) were associated with a higher recurrence. Multivariate recurrence analysis showed that patients with preoperative extrahepatic disease (HR 3.355, P = 0.023) and CEA levels over 20 ng/dL (HR 1.812, P = 0.013) before resection were exposed to a higher recurrence risk. No differences were observed when comparing patients by preoperative number and size of nodules and their lobar distribution. An affected surgical margin was not associated with higher recurrence compared to non-affected margins. When analyzing intraoperative (blood loss, need of blood transfusion, use of Pringle maneuver, type of resection) and postoperative events (biliary leak, postoperative complications, postoperative liver failure) only biliary leakage was associated with an increase in 5-year recurrence rate (0.9% vs 9.5%, P = 0.009) but without differences in survival rates.

Figure 1.

Neoplastic recurrence after hepatic resection.

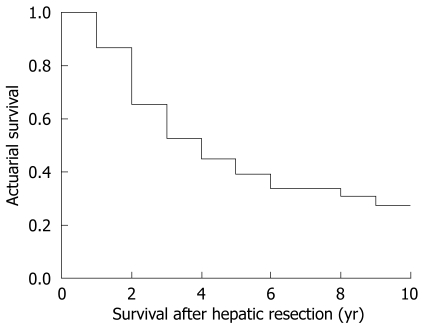

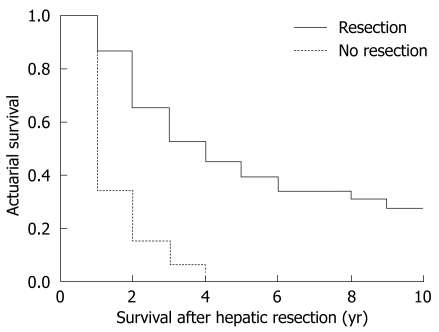

Global survival and unifactorial survival analysis

The global survival at 1, 3 and 5 years in patients undergoing hepatic resection was 91%, 54% and 47%, respectively (Figure 2). Median survival was 3.6 years. Patients undergoing curative hepatic resection had better survival compared to patients in whom a curative resection was not possible (Figure 3). No factors associated with primary CRC tumor were found to make significant differences to patients’ survival, with no differences in survival between patients with synchronous and metachronous CLM. When diagnosed with CLM, the presence of preoperative extrahepatic disease conferred worse survival compared to patients without extrahepatic disease (P = 0.0002) without influence by number and size of CLM. Patients with a preoperative CEA value under 20 ng/dL had better survival compared to patients with CEA over 20 ng/dL (P = 0.035). When analyzing pathological results of CLM, the presence of more than four nodules (P = 0.015) and extrahepatic invasion (P = 0.0044) was associated with worse survival. As with recurrence, intraoperative and postoperative events had no significant effect on survival.

Figure 2.

Global survival post resection.

Figure 3.

Survival for type of surgery.

Multivariate survival analysis

Regarding factors associated with primary CRC tumor, nodal invasion was the only factor accounting for a decreased survival (HR 1.743, P = 0.049). As in the unifactorial survival analysis, preoperative extrahepatic invasion was a significant factor in multivariate analysis (HR 3.223, P = 0.036). After resection, having only one nodule on pathological analysis was a protective factor for survival (HR 2.122, P = 0.042), whereas having nodules over 5 cm was a risk factor for a worse prognosis (HR 2.222, P = 0.049).

Time-related results analysis (Table 4)

Table 4.

Time-related changes by period analysis n (%)

| First period (Jan 1994-Jan 2000) | Second period (Feb 2000-Jan 2006) | P | |

| Patients (male:female) | 93 (63:30) | 143 (90:53) | NS |

| Age (yr) (mean, range) | 63.9 (40-81) | 62.5 (36-81) | NS |

| 1-yr survival rate | 88.3% | 85.6% | NS |

| 1-yr recurrence rate | 38.5% | 44% | NS |

| Anesthetic risk | |||

| ASA I-II | 60 (64.5) | 90 (62.9) | NS |

| ASA III-IV | 33 (35.5) | 53 (37.1) | NS |

| Number nodules | 1.77 (1-6) | 2.3 (1-11) | 0.012 |

| Size of nodules | 3.8 (0.8-11) | 3 (0.2-12) | NS |

| Bilobar disease | 19 (20.4) | 57 (39.9) | 0.002 |

| Extrahepatic disease | 1 (1.1) | 10 (7) | 0.03 |

| Preoperative CEA level (ng/dL) | 13.5 (0.4-3203) | 8.9 (0.6-1715) | 0.03 |

| Adjuvant treatment to CLM | 13 (14) | 49 (34.3) | 0.001 |

| Resectability rate | 69.9% | 86.7% | 0.002 |

| Use of intraoperative US | 91.3% | 92.9% | NS |

| Concordance of IOUS | 56.5% | 67.9% | NS |

| Procedures performed | 0.024 | ||

| Major hepatectomy | 23 (35.4) | 28 (22.6) | |

| Minor hepatectomy | 18 (27.7) | 48 (38.7) | |

| Atypical hepatectomy | 17 (26.2) | 20 (16.1) | |

| Combined hepatectomy | 7 (10.8) | 28 (22.6) | |

| Operative time (min) | 226.7 ± 58.8 | 251 ± 65.3 | 0.01 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 440 (25-1700) | 560 (80-2500) | NS |

| Need of transfusion | 40% | 44.7% | NS |

| Complications rate | 32.3% | 60.5% | 0.001 |

| Minor complications | 24.6% | 54% | 0.001 |

| Major complications | 7.7% | 5.6% | NS |

| Postoperative stay (d) | 11 (5-34) | 9 (4-43) | 0.018 |

| Postoperative mortality | 1.5% | 1.6% | NS |

| Complementary treatment of CLM | 60% | 49.2% | NS |

No differences in overall 1- and 3-year survival (88.3% and 51.9% vs 85.6% and 52.3%) and 1-year recurrence (38.5% vs 44%) were observed between patients in the first time period when compared to patients in the second time period.

When analyzing preoperative factors, patients in the second group had a higher number of CLM, but no differences were found when comparing CLM size in the two groups. Also, patients with bilobar disease and presence of extrahepatic disease were more frequent in the second period. CEA levels were higher in the first period. Adjuvant treatment prior to CLM resection was more frequently used in the second period.

Resectability rate was higher in the second period. The frequency of IOUS use did not differ between periods, and there was only a non-significant trend of better accuracy in the second period. Changes in the distribution of surgical techniques were observed with a higher amount of minor hepatectomies and combined procedures in the second period. Operative time in resected patients was slightly higher in the second period, while there were no differences in blood loss and in the perioperative transfusion rate.

No differences were observed in postoperative mortality between the two periods. Postoperative complications were more often observed in the second period with increased minor complications and a similar major complications rate. Hospital stay was shorter in the second group. A similar amount of patients received complementary treatment after CLM resection.

DISCUSSION

At the present time, surgery remains the only curative treatment for CLM[1,5,6]. Advances in liver surgery, perioperative care, radiological techniques and the introduction of new chemotherapeutical agents have greatly changed resection strategies and have increased the number of patients in whom curative resection can be achieved[1,12–15].

Our series show that the majority of patients had good prognostic preoperative characteristics according to CRS (few and small nodules, unilobular distribution and CEA under 20 ng/dL). Such a patient selection can be a reason to explain a high CLM resection rate achieved (80%), comparable to other major series[19], which enhances our policy of feasibility of resection of CLM with extension of traditional criteria. This preoperative selection would not be complete without the use of IOUS as previously recommended by many authors[20–22]. In our series IOUS showed a clear selection benefit as it detected a preoperative underdiagnosis of CLM leading to non-resection in nearly 15% of the patients. For this reason, we strongly advocate IOUS exploration as a compulsory adjunct prior to liver resection for CLM.

The presence of extrahepatic disease is one of the classical contraindications to CLM resection, a belief which has changed as surgical expertise has made it possible to perform curative resections including all extrahepatic disease[1]. Despite this positive aspect, it has to be noted that the preoperative and the postoperative (pathological) presence of extrahepatic disease in patients with CLM is associated with a higher neoplastic recurrence and a worse patient survival[9,23]. This fact should raise concern regarding need for a stricter patient selection when extrahepatic disease is found on preoperative imaging, as only curative resection is a valid option for these patients[24]. Also, even though no conclusive data exist at the present time, the finding of intraoperative extrahepatic disease probably deserves a closer postoperative follow-up with a more aggressive use of complementary chemotherapeutical treatment.

Definition of an adequate minimal surgical margin when resecting CLM remains an unresolved issue[25,26]. At the present time the ideal margin is yet to be defined as some authors have shown that negative margins of either 1-4 mm, 5-9 mm or up to 1 cm have similar overall recurrence rates and survival[25–27]. In our study differences in recurrence and survival could not be found when comparing free surgical margins under and above 1 cm, a fact that supports these previous observations. Interestingly, a positive surgical margin was not associated with worse survival or higher recurrence in our series, which could be explained by the concept that the really important margin would be the one which remains in the patient, as some studies have pointed[28].

The presence of CLM has been historically linked to a low overall survival, although in recent years the advances in imaging, chemotherapeutical agents and surgical techniques have increased the survival rates, approaching a 5-year survival of 60%[12–15]. In our series 5-year survival in resected patients was 47%, which can be positively compared with other major hepatobiliary center series, although some of these series do not reflect the surgical and perioperative improvements achieved in the last decade[29].

Up to 50% of patients with resected CLM will develop recurrence of neoplastic disease, the majority of them in the first 2 years, and this fact remains the most determinant factor for patient survival[30–34]. Several recurrence-associated factors such as size and number of CLM, stage of the primary tumor, CEA levels, disease-free interval and resection margin have been described; these being the basis for the clinical scores which are used for predicting recurrence and thus survival in patients with CLM[9–11]. In our study we were only able to find preoperative CEA above 20 ng/dL and extrahepatic invasion as significant factors that would be associated with an increased recurrence rate.

Despite the already known effect of preoperative factors, some authors have also pointed to the influence of intraoperative and postoperative events on recurrence and survival[35,36]. Improvements in surgical technique and perioperative management have lead to a decrease in postoperative mortality in major centers, under 5% in the last few years, clearly improving prognosis in patients with CLM[37]. In our series global postoperative mortality was 1.7%, a similar rate when compared to other series from high-volume centers[29]. Interestingly, when analyzing postoperative complications, only biliary leakage was associated with a significantly increased first-year recurrence rate, but had no influence on differences in survival rate. This data should be taken with caution as more studies need to be done in order to confirm this unexpected and difficult to explain observation, but it raises concern about the influence of postoperative events in the prognosis of CLM patients.

Surgical treatment of CLM has been challenged with advances in surgical techniques and better perioperative management in recent times[29,32,36,37]. Our series failed to show an improvement with time in short- and medium-term survival and recurrence as these two parameters did not improve in the second time period. However, similar survival and recurrence rates between the two periods should not be seen as a negative fact because patient conditions could also have changed (and not necessarily improved) with time. In fact, even though no differences in patient basal status were observed in the second period, an increase of unfavorable prognostic factors (higher number of CLM, bilobar distribution, presence of extrahepatic disease) could be found. This extension of indications for CLM resection would be mainly responsible for the limitation of the expected effects of improved surgical experience and use of better technology when resecting CLM. Also, adjuvant treatment of CLM was more frequent in the second period, a fact related to the presence of synchronous (another indicator of bad prognosis) or initially unresectable CLM, situations that would limit improvement in overall survival rates in the second period, as seen in our study.

Resectability rate is said to depend basically on good patient selection and surgical expertise[19], a fact that seems to be confirmed by our series as resectability rate increased with time. Also, the sensitivity for diagnosing CLM with IOUS has increased with time probably as a result of the availability of higher definition instruments and the experience gained by surgeons with this technique[38]. However, preoperative imaging techniques have also improved their limits for CLM diagnosis with time. This would help explain the fact that in our series the concordance rate of preoperative studies and IOUS showed a positive trend with time, although it did not reach significance due to better accuracy in both IOUS and preoperative staging tools[39]. However, and as stated before, sufficient reasons do not exist at the present time to limit IOUS in the staging of CLM.

Our series shows an increase in global postoperative complications with time without any differences in mortality. While mortality rates could be expected to stay the same or decrease due to improved surgical expertise and perioperative care, despite more difficult resections[32,34,36], this increase in complications can be explained easily when dividing them into major and minor events[40]. Major complications are closely related to mortality and for this reason it would be expected that they did not change over time. However, minor complications mainly influence hospital stay and this latter parameter decreased with time in our series. The rationale behind this is that improved awareness and means for detection of minor complications are implemented with time, which would invariably result in better treatment of these complications.

To conclude, it can be stated that despite the extension of indications for resective surgery in the second time period, with an inclusion of patients having more unfavorable prognostic factors, improvements in surgical technique, adjuvant treatments and preoperative imaging have played an important role in avoiding a greater mortality compared to the past. As surgery remains the only curative treatment, a careful patient selection and a judicious use of adjuvant therapies prior to and after surgery are crucial to continue offering patients with CLM a real chance of a cure.

COMMENTS

Background

Although many prognostic factors for survival and neoplastic recurrence of patients undergoing surgical treatment for colorectal liver metastases (CLM) are already identified, the effects of time-related changes in these patients are still poorly studied because of the presence of many involved factors.

Research frontiers

Prognostic factors implicated in survival and recurrence for patients undergoing surgical treatment for CLM are important in order to select better treatment options in these patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The observed effects of time-related changes in morbidity, mortality, overall survival and neoplastic recurrence in patients with CLM result from the inclusion of patients with unfavorable prognostic factors and the recent improvements in preoperative imaging, surgical technique and adjuvant treatments.

Applications

A careful patient selection and judicious use of adjuvant therapies prior to and after surgery are crucial for continuing to improve prognosis in patients with CLM.

Peer review

The manuscript retrospectively reviewed patients who underwent hepatic resection for liver metastases from colorectal cancer, identified prognostic factors for recurrence and survival after hepatic resection, and speculated as to time-related advances of this important disease. The paper is a well-designed work which aims to evaluate the influence of some factors on the recurrence and survival of patients who undergo CLM resection and, to compare these items between two periods.

Supported by An investigation grant from Abertis Infraestructuras S.A

Peer reviewers: Dario Conte, Professor, GI Unit - IRCCS Osp. Maggiore, Chair of Gastroenterology, Via F. Sforza, 35, Milano 20122, Italy; Giuseppe Montalto, Professor, Medicina Clinica e delle Patologie Emergenti, University of Palermo, via del Vespro, 141, Palermo 90100, Italy; Yasuhiko Sugawara, MD, Artificial Organ and Transplantation Division, Department of Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Khatri VP, Petrelli NJ, Belghiti J. Extending the frontiers of surgical therapy for hepatic colorectal metastases: is there a limit? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8490–8499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.6155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson AB 3rd. Epidemiology, disease progression, and economic burden of colorectal cancer. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13:S5–S18. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.s6-c.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bengmark S, Hafström L. The natural history of primary and secondary malignant tumors of the liver. I. The prognosis for patients with hepatic metastases from colonic and rectal carcinoma by laparotomy. Cancer. 1969;23:198–202. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196901)23:1<198::aid-cncr2820230126>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner JS, Adson MA, Van Heerden JA, Adson MH, Ilstrup DM. The natural history of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. A comparison with resective treatment. Ann Surg. 1984;199:502–508. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198405000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma: impact of surgical resection on the natural history. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1241–1246. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neeleman N, Andersson R. Repeated liver resection for recurrent liver cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:893–901. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw IM, Rees M, Welsh FK, Bygrave S, John TG. Repeat hepatic resection for recurrent colorectal liver metastases is associated with favourable long-term survival. Br J Surg. 2006;93:457–464. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318; discussion 318-321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Jaeck D. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Française de Chirurgie. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwatsuki S, Dvorchik I, Madariaga JR, Marsh JW, Dodson F, Bonham AC, Geller DA, Gayowski TJ, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma: a proposal of a prognostic scoring system. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:291–299. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam R, Huguet E, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Kunstlinger F, Levi F, Bismuth H. Hepatic resection after down-staging of unresectable hepatic colorectal metastases. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:211–220, xii. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folprecht G, Grothey A, Alberts S, Raab HR, Köhne CH. Neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable colorectal liver metastases: correlation between tumour response and resection rates. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1311–1319. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung KY, Saltz LB. Antibody-based therapies for colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10:701–709. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-9-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam R, Lucidi V, Bismuth H. Hepatic colorectal metastases: methods of improving resectability. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84:659–671. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bismuth H, Adam R, Lévi F, Farabos C, Waechter F, Castaing D, Majno P, Engerran L. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:509–520; discussion 520-522. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wichmann MW, Hüttl TP, Winter H, Spelsberg F, Angele MK, Heiss MM, Jauch KW. Immunological effects of laparoscopic vs open colorectal surgery: a prospective clinical study. Arch Surg. 2005;140:692–697. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.7.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueras J, Valls C, Rafecas A, Fabregat J, Ramos E, Jaurrieta E. Resection rate and effect of postoperative chemotherapy on survival after surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2001;88:980–985. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makuuchi M, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki S. Intraoperative ultrasonic examination for hepatectomy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1983;Suppl 2:493–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerwenka H, Raith J, Bacher H, Werkgartner G, el-Shabrawi A, Kornprat P, Mischinger HJ. Is intraoperative ultrasonography during partial hepatectomy still necessary in the age of magnetic resonance imaging? Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1539–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rydzewski B, Dehdashti F, Gordon BA, Teefey SA, Strasberg SM, Siegel BA. Usefulness of intraoperative sonography for revealing hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients selected for surgery after undergoing FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:353–358. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.2.1780353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lise M, Bacchetti S, Da Pian P, Nitti D, Pilati P. Patterns of recurrence after resection of colorectal liver metastases: prediction by models of outcome analysis. World J Surg. 2001;25:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s002680020138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bipat S, van Leeuwen MS, Comans EF, Pijl ME, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH, Stoker J. Colorectal liver metastases: CT, MR imaging, and PET for diagnosis--meta-analysis. Radiology. 2005;237:123–131. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371042060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Andres A, Eng C, Curley SA, Loyer EM, Muratore A, Mentha G, et al. Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2005;241:715–722, discussion 722-724. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160703.75808.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cady B, Jenkins RL, Steele GD Jr, Lewis WD, Stone MD, McDermott WV, Jessup JM, Bothe A, Lalor P, Lovett EJ, et al. Surgical margin in hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis: a critical and improvable determinant of outcome. Ann Surg. 1998;227:566–571. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueras J, Burdio F, Ramos E, Torras J, Llado L, Lopez-Ben S, Codina-Barreras A, Mojal S. Effect of subcentimeter nonpositive resection margin on hepatic recurrence in patients undergoing hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Evidences from 663 liver resections. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1190–1195. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busquets J, Pelaez N, Alonso S, Grande L. The study of cavitational ultrasonically aspirated material during surgery for colorectal liver metastases as a new concept in resection margin. Ann Surg. 2006;244:634–635. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000239631.74713.b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentrem DJ, Dematteo RP, Blumgart LH. Surgical therapy for metastatic disease to the liver. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:139–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O'Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125–135. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aa2c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambiru S, Miyazaki M, Isono T, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Shimizu H, Kusashio K, Furuya S, Nakajima N. Hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: analysis of prognostic factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:632–639. doi: 10.1007/BF02234142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M. Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:982–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, Sumetchotimetha W, Rangsin R, Schulick RD, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235:759–766. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doci R, Gennari L, Bignami P, Montalto F, Morabito A, Bozzetti F. One hundred patients with hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer treated by resection: analysis of prognostic determinants. Br J Surg. 1991;78:797–801. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benzoni E, Lorenzin D, Baccarani U, Adani GL, Favero A, Cojutti A, Bresadola F, Uzzau A. Resective surgery for liver tumor: a multivariate analysis of causes and risk factors linked to postoperative complications. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:526–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arru M, Aldrighetti L, Castoldi R, Di Palo S, Orsenigo E, Stella M, Pulitanò C, Gavazzi F, Ferla G, Di Carlo V, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors influencing long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9285-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, Corvera C, Weber S, Blumgart LH. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406; discussion 406-407. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000029003.66466.B3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torzilli G, Makuuchi M. Tricks for ultrasound-guided resection of colorectal liver metastases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Figueras J, Planellas P, Albiol M, López-Ben S, Soriano J, Codina-Barreras A, Pardina B, Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Falgueras L, Ortiz R, et al. [Role of intra-operative echography and computed tomography with multiple detectors in the surgery of hepatic metastases: a prospective study] Cir Esp. 2008;83:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0009-739x(08)70528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]