Abstract

Background

Hyperuricemia is prevalent in chronic kidney disease (CKD); however data are limited on the relationship of uric acid levels with long term outcomes in this patient population.

Study Design

Cohort Study

Setting & Participants

The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study was a randomized controlled trial (N=840), conducted 1989–1993, to examine the effects of strict blood pressure control and dietary protein restriction on progression of stage 3–4 CKD. This analysis included 838 patients.

Predictor

Uric acid

Outcomes & Measurements

The study evaluated the association of baseline uric acid levels with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular (CVD) mortality, and kidney failure.

Results

Mean (SD) age was 52 (12) years, glomerular filtration rate was 33 (12) ml/min/1.73m2, and uric acid was 7.63 (1.66) mg/dl. During a median follow-up of 10 years, 208 (25%) participants died of any cause, 127 (15%) from CVD, and 553 (66%) reached kidney failure. In multivariate models, the highest tertile of uric acid was associated with increased risk of all-cause (HR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.07–2.32]) mortality, a trend towards CVD mortality (HR, 1.47 [95% CI, 0.90–2.39]) and no association with kidney failure (HR, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.95–1.51), compared to the lowest tertile. In continuous analyses, a 1-mg/dl higher uric acid was associated with 17% increased risk of all-cause (HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.05–1.30]), and 16% increased risk of CVD mortality (HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.01–1.33]), but was not associated with kidney failure (HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.97–1.07]).

Limitations

Primary analyses were based on single measurement of uric acid. The results are primarily generalizable to relatively young white patients with predominantly non-diabetic CKD.

Conclusions

In stage 3–4 CKD, hyperuricemia appears to be an independent risk factor for all-cause and CVD mortality but not kidney failure.

INTRODUCTION

Several (1–4) but not all studies (5–8) in the general population have suggested an association between uric acid and cardiovascular outcomes. Many studies have also demonstrated an association of uric acid with established cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. (9–12) Hyperuricemia is highly prevalent in chronic kidney disease (CKD). (13) Thus uric acid may have a role as a uremia related cardiovascular risk factor in CKD. While two studies in patients with kidney failure found a J-shaped association between uric acid and all-cause mortality, (14, 15) this relationship has not been studied in patients in the earlier stages of CKD. It is unclear whether uric acid is a marker for increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality in this patient population and whether the relationship between uric acid and mortality is independent of traditional CVD risk factors.

Given the interrelationship between CVD and progression of CKD, (16) it is possible that uric acid is also a risk factor for progression of kidney disease. Existing data on this relationship are contradictory. While a few studies showed that hyperuricemia was associated with progression of kidney disease, (13, 17–19) others failed to show this relationship.(20) These studies were limited by imprecise measures of kidney function and lack of data on proteinuria.

Using data from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study randomized cohort, we examined whether uric acid is an independent risk factor for the development of outcomes during long-term follow-up in patients with predominantly non-diabetic stage 3–4 CKD.

METHODS

Participants and Measurements

Details of the MDRD Study have been described previously. (21) The MDRD Study was a randomized controlled trial conducted from 1989–1993 that tested the effect of dietary protein restriction and strict blood pressure control on the rate of progression of kidney disease in 840 individuals. Baseline entry criteria included age between 18 and 70 years, serum creatinine of 1.2 to 7 mg/dl in women and 1.4 to 7 mg/dl in men. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, type 1 diabetes, insulin dependent type 2 diabetes, glomerulonephritis due to autoimmune diseases, obstructive uropathy, renal artery stenosis, proteinuria greater than 10 g/day, mean arterial pressure greater than 125 mm Hg, and prior kidney transplantation. Glomerular filtration rate was measured using iothalamate clearance. In Study A (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] 25 to 55 ml/min/1.73 m2) patients were prescribed a usual or low protein diet. In Study B, (GFR 13 to 24 ml/min/1.73 m2), patients were prescribed one of two low protein diets: the same low protein diet as in Study A or a very low protein diet supplemented with a mixture of ketoacids and amino acids. Both studies A and B were combined for the present analysis which includes 838 patients with baseline uric acid measurements. Uric acid was measured at baseline at the MDRD Study Central Biochemistry Laboratory (Department of Biochemistry, Cleveland Clinic Foundation).

Outcomes

We assessed 3 outcomes; all-cause mortality, CVD mortality and kidney failure (defined as requirement for dialysis or transplantation). Survival status and cause of death, through December 31, 2000, was ascertained by review of death certificates using the National Death Index. A death was ascribed to CVD if the primary cause of death was CVD [International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9 code 390-459)] or if kidney disease or diabetes were listed as the primary cause of death and CVD (ICD-9 code 390-459) was the secondary cause of death. Diabetes was defined as ICD 9 code 250.0–250.9. Death due to kidney disease was defined as ICD 9 codes 580–599 &753.1. Kidney failure outcomes were obtained from the U.S. Renal Data System through December the 31st 2000. Data collection procedures were approved by the Cleveland Clinic and Tufts-New England Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution and normality of variables of interest were evaluated using box plots and histograms. Summary statistics by tertiles of uric acid are presented as percentages for categorical data, mean ± standard deviation for approximately normally distributed continuous variables, and median (interquartile range) for skewed continuous variables. Differences between the uric acid groups were tested using the chi square test for categorical variables, ANOVA for approximately normally distributed continuous variables, and the Kruskall Wallis test for skewed continuous variables.

Cox proportional hazards models, stratified by study, were used to evaluate the relationship between uric acid tertiles with all-cause mortality, CVD mortality and kidney failure, initially without adjustment, and subsequently adjusting for several groups of covariates. Covariates were selected for inclusion in the model if P<0.1 in univariate analysis (Table 1) Model 1 adjusted for randomization assignments to protein diets and blood pressure strata, age, and gender. Model 2 adjusted for traditional CVD risk factors including history of CVD, diabetes, body mass index (BMI), high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in addition to the variables in model 1; systolic blood pressure was forced into the model given its known association with uric acid and the outcomes of interest. Model 3 adjusted for variables in model 2 as well as kidney disease factors-GFR, serum albumin, and diuretic use, with additional adjustment for etiology of kidney disease and log transformed proteinuria for the kidney failure outcome, and Model 4 adjusted for Model 3 covariates + allopurinol use. Proportional hazards assumptions were tested using log minus log survival plots, and plots of Schoenfeld residuals versus survival time.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Tertiles of Uric Acid

| Tertile 1 [1.7–6.9 mg/dl] | Tertile 2 [7.0–8.3 mg/dl] | Tertile 3 [8.4–15.6 mg/dl] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=276 | n=288 | n=274 | ||

| Uric Acid (mg/dl) | 5.8±0.9 | 7.6±0.4 | 9.5±0.9 | |

| Demographic Factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 53.0±11.5 | 52.1±12.3 | 50.2±13.2 | 0.03 |

| Men (%) | 50 | 41 | 27 | <0.001 |

| White (%) | 84 | 88 | 83 | 0.3 |

| Current Smoker (%) | 9 | 10 | 10 | 0.8 |

| Cardiovascular Risk Factors | ||||

| Diabetes (%) | 6 | 7 | 3 | 0.06 |

| History of Coronary Artery Disease (%) | 13 | 6 | 10 | 0.03 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 131.2±16.7 | 133.4±18.5 | 131.2±17.4 | 0.3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 80.4±9.5 | 81.2±9.5 | 81.3±11.2 | 0.5 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26.7±4.5 | 27.1±4.5 | 27.6±4.4 | 0.04 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 213.8±46.8 | 217.9±43.2 | 218.4±45.8 | 0.4 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 145.8±42.9 | 149.0±40.3 | 147.7±40.7 | 0.7 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 42.4±15.1 | 40.4±13.8 | 36.8±13.3 | <0.001 |

| C-reactive Protein (mg/dl) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 |

| Kidney Disease Factors | ||||

| Glomerular Filtration Rate (ml/min/1.73m2) | 34.2±12.5 | 32.6±12.2 | 30.6±10.9 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.0±0.3 | 4.0±0.4 | 4.1±0.3 | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria (g/d) | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.4 (1.7) | 0.3 (1.5) | 0.2 |

| Etiology of Kidney Disease (%) | ||||

| Polycystic kidney disease | 38 | 29 | 33 | |

| Glomerular disease | 34 | 35 | 34 | 0.3 |

| Other | 28 | 36 | 33 | |

| Medications | ||||

| Allopurinol (%) | 33 | 10 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Diuretics (%) | 33 | 34 | 46 | 0.01 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Conversion factors for units: Uric Acid in mg/dL to μmol/L, x59.48; Total, HDL, and LDL Cholesterol in mg/dL to mmol/L, x0.02586; GFR in mL/min/1.73m2 to mL/s/1.73m2, x 0.01667; and albumin in g/dL to g/L, x10.

To maximize statistical power to examine the relationship between uric acid and mortality, continuous variable analyses were conducted with hazard ratios (HR) presented per 1mg/dl higher uric acid. We performed 2 multivariable models corresponding to the previously described Models 3 and 4. Hazard ratios for these models are presented per 1mg/dl higher uric acid.

Finally, since high uric acid levels may lead to hypertension, and hypertension may be in the causal pathway between uric acid and the outcomes, the fully adjusted models for all-cause and CVD mortality, and kidney failure, were repeated without adjustment for systolic blood pressure.

The models for the mortality outcomes included patients who developed kidney failure and were censored only at death or the end of follow-up, while the models for kidney failure were censored at kidney failure, death, or the end of follow-up.

Sensitivity Analyses

Since allopurinol lowers uric acid levels, individuals treated with allopurinol may in fact be misclassified in the “low” uric acid group despite having been exposed to high uric acid levels for extended periods. We therefore repeated the analyses 1) categorizing the sample into two groups based on the presence of hyperuricemia defined as either taking allopurinol or serum uric acid > 9mg/dl (men) or > 8mg/dl (women). This definition was based on analyses from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (6) and 2) excluding the 143 participants who reported allopurinol use. Cox proportional hazards models, stratified by study, were used to evaluate the relationship of uric acid tertiles excluding patients on allopurinol and hyperuricemia with all-cause and CVD mortality, initially without adjustment, and subsequently adjusting for the following covariates selected on the basis of p<0.1 in univariate analysis: age, gender, blood pressure and dietary protein randomization assignments, history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, body mass index, HDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, log transformed C-reactive protein, glomerular filtration rate, serum albumin, diuretic and allopurinol use We also adjusted for log transformed proteinuria and etiology of kidney disease for the kidney failure and composite outcome.

RESULTS

The mean (SD) age of the study cohort was 52 (12) years, 85% were white, 61% men and 5% had diabetes. Mean (SD) GFR and uric acid were 33 (12) ml/min/1.73m2 and 7.63 (1.66) mg/dl respectively. A total of 145 patients (17%) were on allopurinol at baseline.

Baseline Characteristics By Tertile Of Uric Acid

Patients in the highest tertile of uric acid were more likely to be female, younger, have higher BMI, higher serum albumin, lower HDL cholesterol and levels of GFR (Table 1). The prevalence of coronary artery disease, diabetes, and allopurinol use was highest in the lowest tertile of uric acid.

Uric Acid And All Cause Mortality

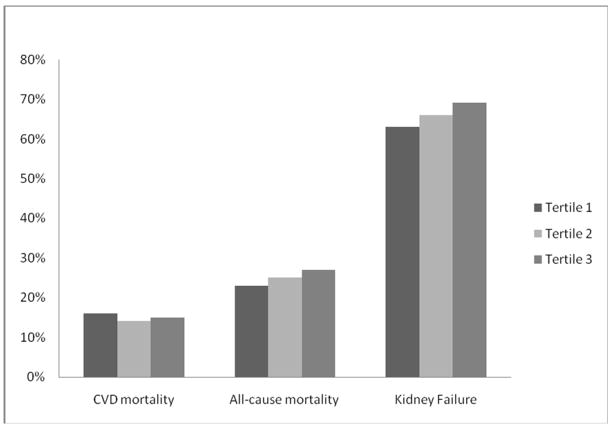

Twenty five percent (n= 208) of participants died during a median follow-up period of approximately 10 years. Crude all-cause mortality rates were 23%, 25% and 27% in uric acid tertiles 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure 1). In unadjusted Cox models there was no association between tertiles of uric acid and all cause mortality. This relationship became significant after adjustment for demographic factors, dietary intervention, CVD risk factors, kidney disease risk factors; diuretic and allopurinol use (Table 2). We believe the discrepancy between the unadjusted and adjusted models reflects the younger age, higher numbers of women, and lower prevalence diabetes mellitus (DM) and CVD in the highest tertile of uric acid as seen in Table 1. Of note, prevalence of allopurinol use was highest in the lowest tertile suggesting that treated patients with hyperuricemia were included in this lower tertile thus accounting for the worse CVD risk profile in this group. Hazard ratios did not change appreciably when systolic blood pressure was excluded from the model (HR for tertile 2 versus tertile 1, 1.26 [95% CI, 0.89–1.79]; HR for tertile 3 versus tertile 1, 1.54 [1.07–2.20]).

Figure 1.

Crude Rates of Clinical Outcomes by Uric Acid Tertiles

Table 2.

Relationship Between Tertiles Of Uric Acid and All-Cause Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality and Kidney Failure

| Tertile 1 [1.7–6.9 mg/dl] | Tertile 2 [7.0–8.3mg/dl] | Tertile 3 [8.4–15.6 mg/dl] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=276) | (n=288) | (n=274) | |

| All Cause mortality | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.13, 0.81–1.59 | 1.20, 0.86–1.69 |

| Model 1† | 1.00 (ref) | 1.21, 0.86–1.69 | 1.34, 0.95–1.88 |

| Model 2‡ | 1.00 (ref) | 1.29, 0.91–1.86 | 1.53, 1.08–2.18 |

| Model 3§ | 1.00 (ref) | 1.22, 0.86–1.73 | 1.50, 1.05–1.90 |

| Model 4£ | 1.00 (ref) | 1.27, 0.88–1.84 | 1.57, 1.07–2.32 |

| Cardiovascular Disease Mortality | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 0.88, 0.57–1.35 | 0.97, 0.64–1.48 |

| Model 1† | 1.00 (ref) | 0.93, 0.61–1.43 | 1.09, 0.71–1.67 |

| Model 2‡ | 1.00 (ref) | 0.98, 0.63–1.52 | 1.33, 0.86–2.08 |

| Model 3§ | 1.00 (ref) | 0.94, 0.60–1.46 | 1.28, 0.82–2.00 |

| Model 4£ | 1.00 (ref) | 1.05, 0.66–1.68 | 1.47, 0.90–2.39 |

| Kidney Failure | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.23, 0.99–1.51 | 1.16, 0.94–1.43 |

| Model 1† | 1.00 (ref) | 1.21, 0.98–1.49 | 1.08, 0.87–1.33 |

| Model 2‡ | 1.00 (ref) | 1.18, 0.96–1.46 | 1.10, 0.89–1.36 |

| Model 3§1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.11, 0.90–1.37 | 1,12, 0.90–1.39 |

| Model 4£ | 1.00 (ref) | 1.18, 0.94–1.47 | 1.20, 0.95–1.51 |

Entries are Hazard Ratio, 95% Confidence Interval

Adjusted for age, gender, and blood pressure and protein diet randomization assignments

Adjusted for Model 1 covariates + history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Adjusted for Model 2 covariates + glomerular filtration rate, serum albumin, and diuretic for both outcomes and additional adjustment for etiology of kidney disease and log transformed proteinuria for the kidney failure outcome

Adjusted for Model 3 covariates + allopurinol

The analyses were repeated with uric acid as a continuous variable; there was no association in unadjusted analysis (HR per 1 mg/dl higher uric acid, 1.07 [95% CI, 0.99–1.16]), however, in the fully adjusted model, a 1mg/dl higher uric acid was associated with a 17% increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.05–1.30]). As with the categorical analyses, differences in gender distribution, age, and CVD risk profile appears to account for the differences between the univariate and multivariable associations.

Uric Acid And CVD Mortality

Fifteen percent (n=127) of participants died from CVD during a median follow-up period of approximately 10 years. Crude CVD mortality rates were 16%, 14% and 15% in uric acid tertiles 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure 1). In unadjusted Cox models there was no association between tertiles of uric acid and CVD mortality (Table 2). In the multivariate Cox models adjusting for demographic factors, dietary intervention, CVD risk factors, kidney disease risk factors, diuretic and allopurinol use, there was a trend towards increased risk in the relationship between uric acid and CVD mortality that did not reach statistical significance. Hazard ratios did not change appreciably when systolic blood pressure was excluded from the model (HR for tertile 2, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.65–1.56]; HR for tertile 3, 1.33 [0.85–2.09]).

The analyses were repeated with uric acid as a continuous variable. While high levels of uric acid were not associated with increased risk of CVD mortality in unadjusted analysis (HR per 1 mg/dl higher uric acid, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.92–1.14]), adjustment for covariates resulted in a significant relationship (HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.01–1.33]). As stated earlier, we believe the discrepancy between the unadjusted and adjusted models reflects the more favorable CVD profile in the highest tertile group.

Uric Acid And Kidney Failure

Sixty six percent (n=553) of participants reached kidney failure during a median follow up of approximately 6 years. Crude kidney failure rates were 63%, 66% and 69% in uric acid tertiles 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure 1). In unadjusted Cox models there was no association between tertiles of uric acid and kidney failure. After adjustment for demographic factors, dietary intervention, CVD risk factors, kidney disease risk factors, diuretic and allopurinol use, there was no association between uric acid and development of kidney failure (Table 2). HRs did not change appreciably when systolic blood pressure was excluded from the model (HR for tertile 2, 1.15 [95% CI, .93–1.42]; HR for tertile 3, 1.13 [0.91–1.41]).

The analyses were repeated with uric acid as a continuous variable. Higher levels of uric acid were not associated with increased risk of kidney failure in unadjusted analysis (HR per 1 mg/dl higher uric acid, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.99–1.09]) or fully adjusted models (HR per mg/dl higher uric acid, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.97–1.07]).

Sensitivity Analyses

We repeated the analyses categorizing the sample into two groups based on the presence of hyperuricemia defined as either taking allopurinol or serum uric acid > 9mg/dl (men) or > 8mg/dl (women) (Table 3). Forty one percent (n=340) of participants had hyperuricemia at baseline. Unadjusted rates of all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and kidney failure were 28%, 19%, and 69% in the hyperuricemia group versus 23%, 12%, and 64% in the normal uric acid group. Hyperuricemia was associated with a 51% increased risk of CVD mortality in unadjusted and 59% in adjusted Cox models; there was no association with all-cause mortality or kidney failure in unadjusted or adjusted models. Results in the sub-group not taking allopurinol were consistent with the results of the primary analyses (data not shown).

Table 3.

Hyperuricemia and All-Cause Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality and Kidney Failure

| All-Cause Mortality | CVD Mortality | Kidney failure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted† | 1.21, 0.92–1.59 | 1.51, 1.06–2.13 | 1.04, 0.88–1.23 |

| Adjusted† | |||

| Model 1‡ | 1.20, 0.91–1.58 | 1.52, 1.07–2.16 | 1.02, 0.86–1.21 |

| Model 2§ | 1.20, 0.89–1.61 | 1.68, 1.15–2.46 | 1.02, 0.85–1.22 |

| Model 3¶ | 1.16, 0.86–1.56 | 1.59, 1.09–2.34 | 1.06, 0.88–1.28 |

Entries are Hazard Ratio, 95% Confidence Interval. The Reference group is normal uric acid (n=499) versus hyperuricemia (n=340) defined as allopurinol use or uric acid>9mg/dl in men and >8mg/dl in women.

Stratified by Study

Adjusted for age, gender, and blood pressure and protein diet randomization assignments

Adjusted for Model 1 covariates + history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, body mass index, high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and log transformed C-reactive protein

Adjusted for Model 2 covariates + glomerular filtration rate, serum albumin, diuretic use + log transformed proteinuria and etiology of kidney disease for the kidney failure and composite outcome

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of patients with predominantly non diabetic CKD, hyperuricemia appears to be associated with an increased risk of CVD and all cause mortality but not kidney failure in long-term follow-up.

Several studies have evaluated uric acid as a CVD risk factor in the general population with contradictory results. In a population-based study of epidemiological follow-up data from 5926 participants of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study, uric acid was an independent predictor of CVD mortality. (3) The relationship between uric acid and increased risk of CVD was also observed in cohorts of healthy men, (22) women, (1) the elderly (2) and individuals at high risk for coronary disease. (23)

In contrast, in 6763 participants from the Framingham Heart Study, uric acid did not increase the risk for coronary heart disease, CVD mortality or all-cause mortality in adjusted analyses. (5) Similarly, 2 other population-based cohorts, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study (6) and the British Regional Heart Study (7) failed to find an association between uric acid and CVD outcomes.

Hyperuricemia is highly prevalent in CKD raising interest in it as a potentially modifiable CVD risk factor in this high-risk patient population. Two studies have examined the relationship between uric acid and CVD in patients with kidney failure treated by dialysis. In a cohort of 294 incident patients with CKD stage 5, there was a “J-shaped” association of uric acid with all-cause mortality. (15) Similar results were seen in a cohort of 146 patients on chronic hemodialysis where the lowest and highest quintiles of uric acid levels had a higher risk of all-cause mortality. (14)

Data on the relationship between uric acid and CVD outcomes in the earlier stages of CKD prior to reaching kidney failure are limited. A recent analysis examining the impact of nontraditional cardiovascular disease risk factors on CVD outcomes in 1678 patients with estimated GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2, uric acid was not an independent predictor of a composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality. (24) In contrast, in a cohort of individuals with normal kidney function, baseline uric acid was associated with the composite outcome of death and incident CKD. (25)

In the MDRD Study randomized cohort, increased uric acid levels were independently associated with increased risk of all-cause and CVD mortality after adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors. Our results were unchanged by adjustment for blood pressure suggesting that perhaps the increased risk was independent of any relationship between uric acid and blood pressure and may involve other mechanisms. Putative mechanisms include inflammation, (26) endothelial dysfunction,(27) and vascular smooth muscle proliferation.(28) We acknowledge however that blood pressure was closely targeted during the trial and we are not able to adjust for changes in blood pressure through extended follow-up.

Despite multiple epidemiological and prospective studies, the role of uric acid in the progression of kidney disease and development of kidney failure remains controversial. Two studies demonstrated that hyperuricemia was an independent risk factor for progression of IgA nephropathy. (18, 29) In a study of 6400 individuals with normal kidney function at baseline, uric acid levels of >8.0 mg/dl were associated with a 2.9 and 10 fold increased risk for developing CKD (defined as creatinine >1.2 mg-dl in women and 1.4 mg/dl in men) within 2 years in men and women, respectively. (17) A recent study including 13,338 individuals with normal kidney function, based on estimated GFR, evaluated the relationship between uric acid and incident kidney disease (defined as GFR decrease >/=15 ml/min/1.73 m2 with final GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2). During a follow-up period of 8.5 years, each 1-mg/dl higher uric acid at baseline was associated with an approximately 10% increase in the risk of incident kidney disease in multivariable adjusted models.(25) A randomized trial of allopurinol versus placebo in 54 patients with stage 3–4 CKD, found slower progression (defined as creatinine level increased more than 40% of baseline or need for replacement therapy) in the allopurinol group during a 1-year follow-up. (30) In a population-based study from Japan, hyperuricemia, defined as serum uric acid > or = 6.0 mg/dl, was an independent risk factor for kidney failure. (31) In contrast, in an analysis that included 5808 participants from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), although there was a modest association between uric acid and progression of CKD (defined as a decrease in GFR of more than 3ml/min/1.73m2 per year), there was no association between uric acid and incident CKD (defined as an estimated GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2). (13)

In our study cohort of patients with predominantly non-diabetic stage 3–4 CKD uric acid was not an independent risk factor for the development of kidney failure. There are a few potential explanations for our findings. First, we adjusted for iothalamate GFR as a measure of level of kidney function; it is possible that other studies may been limited by residual confounding from using less precise measures of kidney function. Second, most other studies have looked at incident CKD in a cohort with normal kidney function at baseline. It is possible that uric acid may not be an important contributor to progression in established kidney disease especially in the presence of powerful risk factors for progression of CKD such as proteinuria and high blood pressure. Third, in the MDRD trial patients were randomized to two different targets of blood pressure control. In fact, in the long term follow up of the study, patients randomized to the low blood pressure group had delayed onset of kidney failure. (32) If hypertension is in the pathway relating uric acid to progression of kidney disease, the strict blood pressure control could have blunted the effect of hyperuricemia on the development of hypertension and subsequent kidney failure. However, our results did not change with exclusion of systolic blood pressure from the models.

There are a few limitations in this study. First a single baseline measurement of uric acid was used to predict events several years in the future. However, there is a precedent for this and several previous studies have used this approach. (3, 17, 25) Second, it is possible we failed to observe a significant relationship with CVD mortality in the tertile analyses due to inadequate statistical power. However the additional analyses are consistent with this increased risk. It is important to acknowledge that the results are primarily generalizable to relatively young white patients with predominantly non-diabetic CKD. It is possible that measures of association between uric acid and CVD are even greater in other populations where excess adiposity and diabetes are prevalent. However, this is a large cohort of patients with stage 3–4 CKD with a wide range of kidney function ascertained using iothalamate GFR. The participants are non-diabetic, and are neither appreciable malnourished nor acutely ill. This minimizes the limitation of confounding due to comorbid conditions such as malnutrition, diabetes, and preexisting CVD.

In conclusion, hyperuricemia in persons with CKD appears to be associated with an increased risk for all cause and CVD mortality but not kidney failure. Uric acid may represent an important therapeutic target for mitigating CVD risk in CKD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (National Institutes of Health) grants K23 DK067303, K23 DK02904, K24 DK078204, UO1 DK35073, and TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc.

Footnotes

N section: Because an author of this manuscript is an editor for AJKD, the peer-review and decision-making processes were handled entirely by an Associate Editor (Peter McCullough, MD, MPH, William Beaumont Hospital) who served as Acting Editor-in-Chief. Details of the journal’s procedures for potential editor conflicts are given in the Editorial Policies section of the AJKD website.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bengtsson C, Lapidus L, Stendahl C, Waldenstrom J. Hyperuricaemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and overall death. A 12-year follow-up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Acta Med Scand . 224:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casiglia E, Spolaore P, Ginocchio G, Colangeli G, Di Menza G, Marchioro M, Mazza A, Ambrosio GB. Predictors of mortality in very old subjects aged 80 years or over. Eur J Epidemiol . 9:577–586. doi: 10.1007/BF00211430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang J, Alderman MH. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Jama . 283:2404–2410. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liese AD, Hense HW, Lowel H, Doring A, Tietze M, Keil U. Association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality and incident myocardial infarction in the MONICA Augsburg cohort. World Health Organization Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Diseases. Epidemiology . 10:391–397. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med . 131:7–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moriarity JT, Folsom AR, Iribarren C, Nieto FJ, Rosamond WD. Serum uric acid and risk of coronary heart disease: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Ann Epidemiol . 10:136–143. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Whincup PH. Serum urate and the risk of major coronary heart disease events. Heart . 78:147–153. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reunanen A, Takkunen H, Knekt P, Aromaa A. Hyperuricemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality. Acta Med Scand Suppl . 668:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1982.tb08521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feig DI, Nakagawa T, Karumanchi SA, Oliver WJ, Kang DH, Finch J, Johnson RJ. Hypothesis: Uric acid, nephron number, and the pathogenesis of essential hypertension. Kidney Int . 66:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taniguchi Y, Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Endo G, Fujii S, Okada K. Serum uric acid and the risk for hypertension and Type 2 diabetes in Japanese men: The Osaka Health Survey. J Hypertens . 19:1209–1215. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jossa F, Farinaro E, Panico S, Krogh V, Celentano E, Galasso R, Mancini M, Trevisan M. Serum uric acid and hypertension: the Olivetti heart study. J Hum Hypertens . 8:677–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagahama K, Iseki K, Inoue T, Touma T, Ikemiya Y, Takishita S. Hyperuricemia and cardiovascular risk factor clustering in a screened cohort in Okinawa, Japan. Hypertens Res . 27:227–233. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chonchol M, Shlipak MG, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B, Carney JK, Fried LF. Relationship of uric acid with progression of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis . 50:239–247. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu S-P, Pai M-F, Peng Y-S, Chiang C-K, Ho T-I, Hung K-Y. Serum uric acid levels show a ‘J-shaped’ association with all-cause mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant . 19:457–462. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suliman ME, Johnson RJ, Garcia-Lopez E, Qureshi AR, Molinaei H, Carrero JJ, Heimburger O, Barany P, Axelsson J, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. J-shaped mortality relationship for uric acid in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis . 48:761–771. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsayed EF, Tighiouart H, Griffith J, Kurth T, Levey AS, Salem D, Sarnak MJ, Weiner DE. Cardiovascular disease and subsequent kidney disease. Arch Intern Med . 167:1130–1136. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iseki K, Oshiro S, Tozawa M, Iseki C, Ikemiya Y, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia on the early detection of renal failure in a cohort of screened subjects. Hypertens Res . 24:691–697. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syrjanen J, Mustonen J, Pasternack A. Hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperuricaemia are risk factors for progression of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant . 15:34–42. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bo S, Cavallo-Perin P, Gentile L, Repetti E, Pagano G. Hypouricemia and hyperuricemia in type 2 diabetes: two different phenotypes. Eur J Clin Invest . 31:318–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fessel WJ. Renal outcomes of gout and hyperuricemia. Am J Med . 67:74–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med . 330:877–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strasak A, Ruttmann E, Brant L, Kelleher C, Klenk J, Concin H, Diem G, Pfeiffer K, Ulmer H. Serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular mortality: a prospective long-term study of 83,683 Austrian men. Clin Chem . 54:273–284. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.094425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Short RA, Johnson RJ, Tuttle KR. Uric acid, microalbuminuria and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. Am J Nephrol . 25:36–44. doi: 10.1159/000084073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, Griffith JL, Salem DN, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. The relationship between nontraditional risk factors and outcomes in individuals with stage 3 to 4 CKD. Am J Kidney Dis . 51:212–223. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, Griffith JL, Salem DN, Levey AS. Uric Acid and Incident Kidney Disease in the Community. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1204–11. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RJ, Kang DH, Feig D, Kivlighn S, Kanellis J, Watanabe S, Tuttle KR, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Herrera-Acosta J, Mazzali M. Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease? Hypertension . 41:1183–1190. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000069700.62727.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoccali C, Maio R, Mallamaci F, Sesti G, Perticone F. Uric acid and endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol . 17:1466–1471. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao GN, Corson MA, Berk BC. Uric acid stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by increasing platelet-derived growth factor A-chain expression. J Biol Chem . 266:8604–8608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohno I, Hosoya T, Gomi H, Ichida K, Okabe H, Hikita M. Serum uric acid and renal prognosis in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephron . 87:333–339. doi: 10.1159/000045939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siu YP, Leung KT, Tong MK, Kwan TH. Use of allopurinol in slowing the progression of renal disease through its ability to lower serum uric acid level. Am J Kidney Dis . 47:51–59. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, et al. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:642–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarnak MJ, Greene T, Wang X, Beck G, Kusek JW, Collins AJ, Levey AS. The effect of a lower target blood pressure on the progression of kidney disease long-term follow-up of the modification of diet in renal disease study. Ann Intern Med . 142:342–351. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]